Published online Apr 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i7.1278

Peer-review started: December 24, 2019

First decision: March 5, 2020

Revised: March 18, 2020

Accepted: March 22, 2020

Article in press: March 22, 2020

Published online: April 6, 2020

Processing time: 103 Days and 9.3 Hours

Monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T cell lymphoma (MEITL) is a rare extra-nodal T-cell lymphoma that has uniformly aggressive features with a poor prognosis. No standardized treatment protocols have been established. Previous experience has demonstrated favorable outcomes with combination chemotherapy followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. However, many patients are unable to tolerate the toxicities. Chidamide is a new histone deacetylase inhibitor that has shown preferential efficacy in mature T-cell lymphoma.

We herein present two cases of MEITL who were both intermediate risk according to enteropathy-associated T cell lymphoma prognostic index. Case one was a 61-year-old man. He complained of upper abdominal pain and intermittent black stool for 2 mo. Imaging examination revealed that the intestinal wall was thickened. He received a partial excision of the small intestine. A chidamide-based combination regimen was given postoperatively. Eleven months later, he presented with recurrence in the bilateral lungs. He passed away 15 mo after his diagnosis. Case two was a 35-year-old woman who complained of abdominal distention for 1 mo. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography demonstrated wall thickening of the small intestine and upper sigmoid colon. Colon perforation and septic shock occurred on the fourth day of her admission. She was treated by sigmoid colostomy. Chidamide-based combination therapy was then provided. She was recurrence-free for 6 mo until lesions were found in the bilateral brain and lived for 17 mo since her diagnosis. Compared to historical data, chidamide seems to improve the prognosis of MEITL slightly.

MEITL is a type of aggressive lymphoma. Chidamide is a new promising approach for the treatment of MEITL.

Core tip: Monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T cell lymphoma (MEITL) is a rare and aggressive disease with a poor prognosis. No standardized treatment has been established yet. We report two cases of patients with MEITL who were treated by radical resection followed by chidamide combined with chemotherapy and review the literature focusing on histopathological characteristics, etiology, diagnosis, treatment strategies, and outcomes of MEITL. This report will improve our understanding of MEITL.

- Citation: Liu TZ, Zheng YJ, Zhang ZW, Li SS, Chen JT, Peng AH, Huang RW. Chidamide based combination regimen for treatment of monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T cell lymphoma following radical operation: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(7): 1278-1286

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i7/1278.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i7.1278

Enteropathy-associated T cell lymphoma (EATL) is a rare and aggressive type of peripheral T cell lymphoma. It arises from T lymphocytes residing in the intra-epithelial space of the intestine[1]. It represents 10%–25% of primary gastrointestinal lymphomas and 5%–8% of all T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas[2]. It was classified into two types (type I and type II) according to the World Health Organization (WHO) (2008) classification based on disparities in the epidemiologic and clinicopathological features[3]. EATL type II, which comprises 10% to 20% of all EATL cases, was reclassified as monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T cell lymphoma (MEITL) according to the WHO (2016) classification[4]. It appears to occur sporadically in Asian countries where the incidence of celiac disease is low[5].

The prognosis of MEITL has been considered poor with a median survival of 7 mo after diagnosis[4,6]. Owing to the rarity and geographical variation of the disease, prospective and randomized clinical trials are difficult to be carried out in order to evaluate new treatment regimens incorporating novel agents. As a result, there are no validated and standardized treatment protocols for MEITL. Previous experience obtained favorable outcomes with combination chemotherapy followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant in patients who can tolerate such administration[5]. Nevertheless, the overall prognosis is still poor. Additionally, many patients are unable to tolerate the toxicities of intensive therapy. Further studies are needed to explore effective novel regimens that can improve outcomes in this rare disease entity. Chidamide is one of the five histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs) which has been approved in China[7]. It is a novel orally active benzamide-type histone deacetylase inhibitor. Outcomes from phase I and phase II trials showed preferential efficacy in mature T-cell lymphoma[8]. The efficacy of chidamide in MEITL has not been reported yet.

In this paper, we present two patients with MEITL who were given chidamide combined with chemotherapy after radical surgery. We also discuss the histopathological characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment strategies of MEITL in this paper.

Case 1: Upper abdominal pain and intermittent black stool for 2 mo and up to 15 kg of weight lost.

Case 2: Abdominal distention over a period of 1 mo.

None.

Case 1: No special physical signs were found at the first visit.

Case 2: Physical examination showed no special signs.

Case 1: Pathologic specimens demonstrated diffuse infiltration of medium-sized tumor cells in the small intestine. The karyotype was slightly irregular with visible nucleoli. The cytoplasm was eosinophilic or transparent. The tumor cells were diffusely distributed and infiltrated the whole intestinal wall. Necrosis and vascular invasion were also observed. Immunohistochemistry revealed that the neoplastic cells displayed CD56+, TIA-1+, Granzyme B+, CD3+, CD79a-, CD20-, CD4-, CD8-, CD2-, Perforin-, CD5-, EBERS-, and a high proliferation index (Ki67 index of 80%). A bone marrow aspirate showed normal cellularity and absence of neoplastic cells.

Case 2: Stool examination revealed occult blood. An immunohistochemical test showed that the tumor was positive for TIA-1, Granzyme B, CD3, and CD56, and negative for Perforin, CD20, and CD5. EBER was negative. Additionally, approximately 60% of the tumor cells were Ki-67 positive. Staging bone marrow examination showed no infiltration.

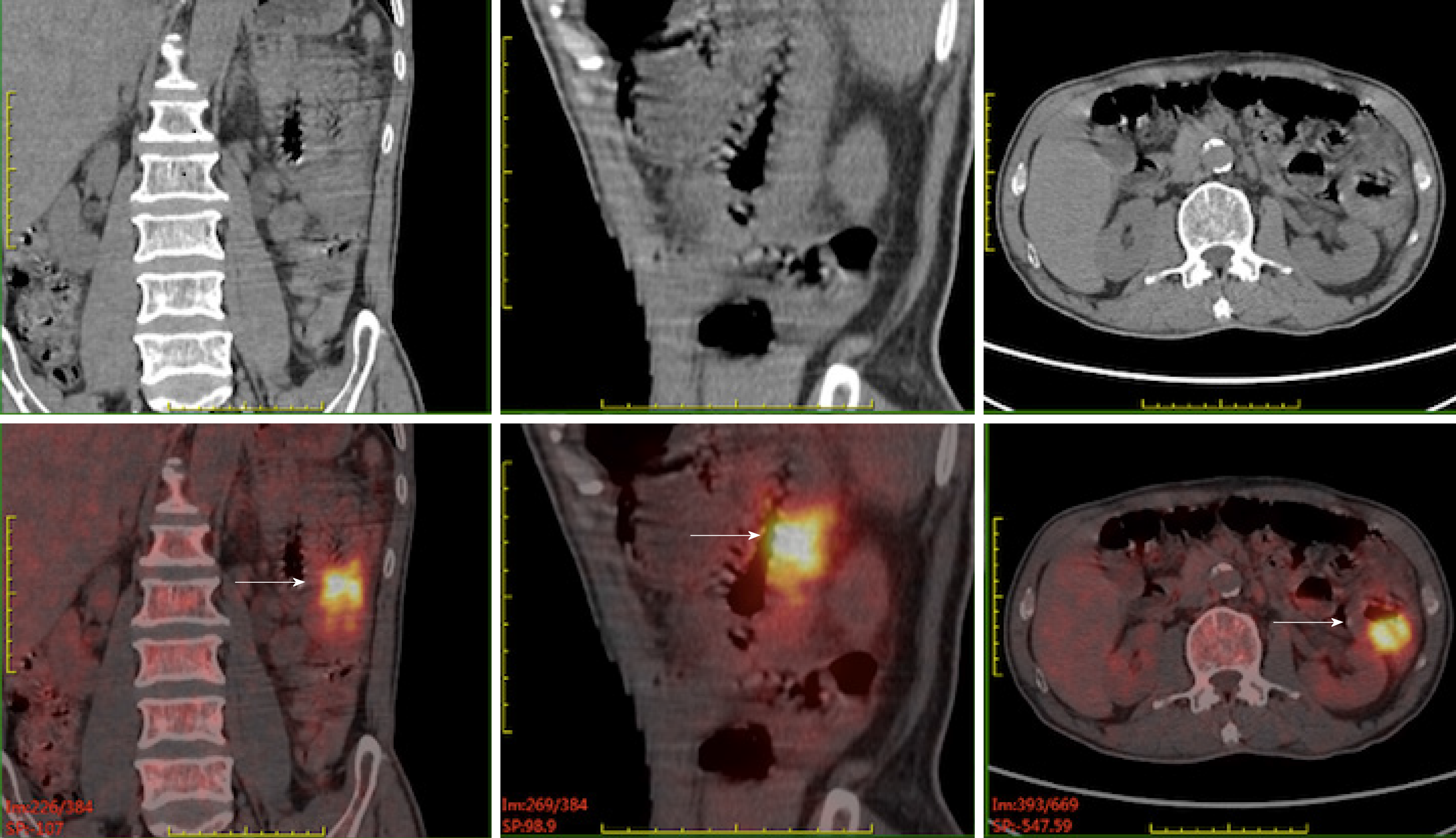

Case 1: A Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan revealed that the wall of the second group of the intestine was thickened with increased metabolism. Multiple enlarged and hypermetabolic lymph nodes in the para-intestinal, mesenteric, and retroperitoneal regions were shown (Figure 1).

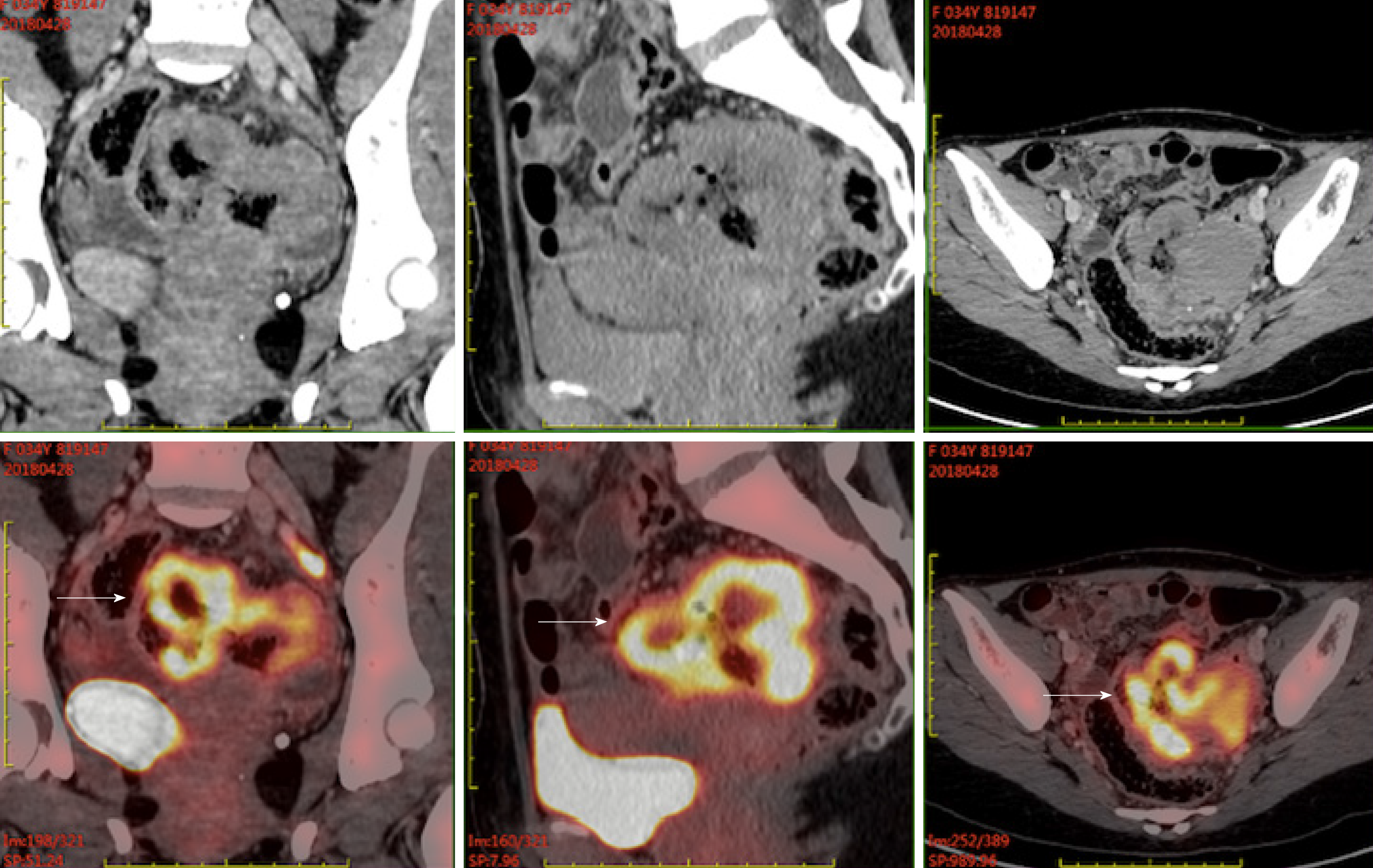

Case 2: PET/CT demonstrated wall thickening of groups 1 and 4 of the small intestine and upper sigmoid colon with diffuse uptake. Furthermore, small lymph nodes in the para-intestinal and mesenteric regions were also metabolically active (Figure 2).

The diagnosis was consistent with MEITL. According to the new EATL prognostic index (EPI), he was defined as intermediate risk[9].

MEITL infiltrating the whole intestinal wall of the jejunum, small intestine, and sigmoid colon was demonstrated by histologic examination. Sixteen mesenteric lymph nodes were resected with no tumor involvement. She was also considered intermediate risk according to EPI.

A partial excision of the small intestine was performed to remove the tumor. After surgery, two cycles of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) combined with chidamide were offered. Treatment was subsequently escalated to CHOEP (CHOP and etoposide) combined with chidamide for four cycles considering the malignant characteristic of this disease.

On day 4 after admission, she felt severe abdominal pain and high fever (her highest temperature was 39.2 °C). Abdominal plain film indicated intestinal perforation. On the fifth day, her blood pressure decreased to 79/49 mmHg, and septic shock was considered. Emergency laparotomy was performed. A perforation occurred in the sigmoid colon was found. Eventually, sigmoid colostomy was executed. After surgery, she received combination chemotherapy with a regimen of IVE (ifosfamide, etoposide, and vincristine) and chidamide for six cycles.

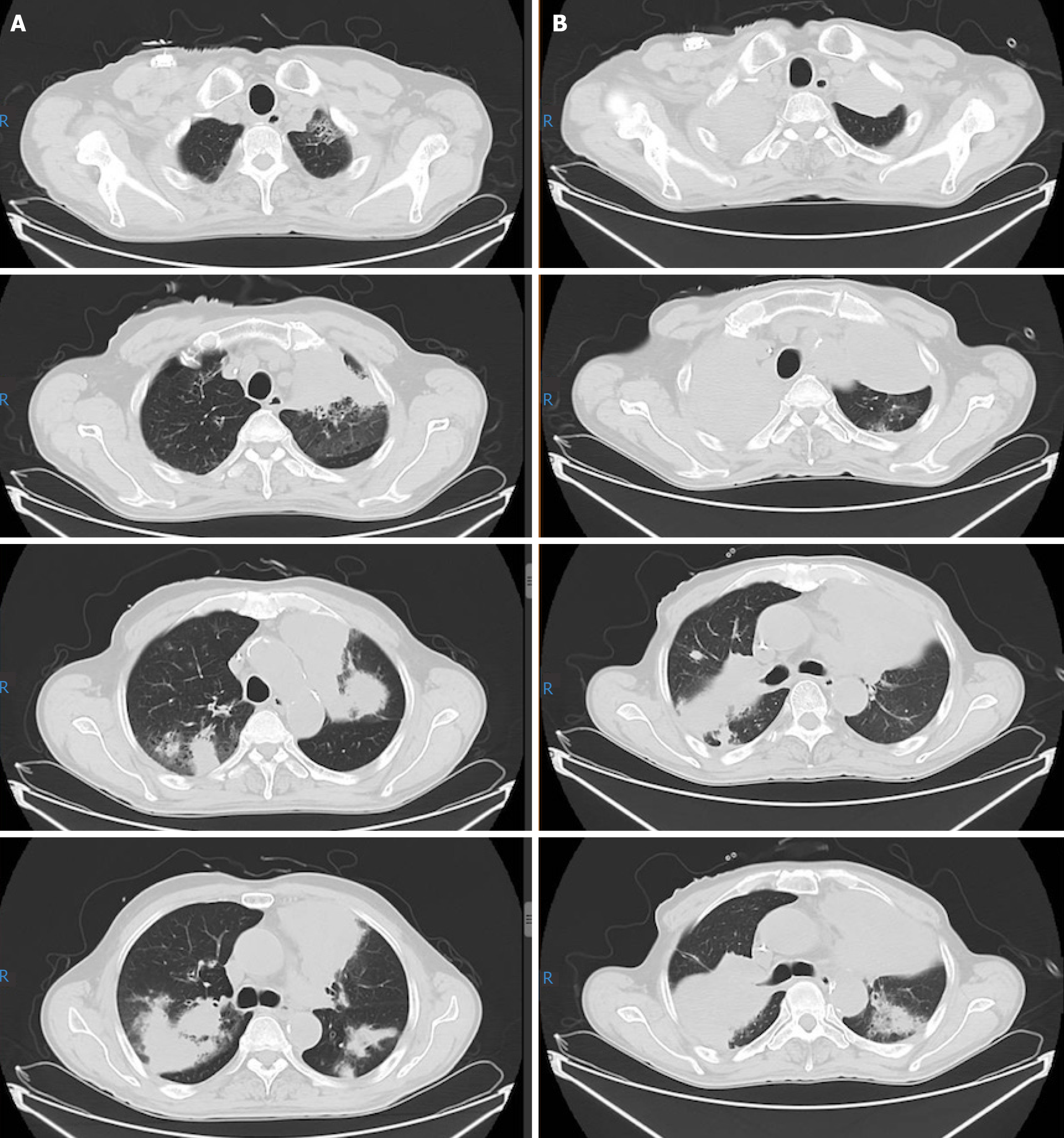

In the middle of chemotherapy, a PET/CT re-evaluation showed no evidence of abnormal hypermetabolic lesion, which confirmed a complete remission. The patient decided to discontinue chemotherapy because of his fragile constitution. Eleven months following his diagnosis, he complained of recurrent cough and sputum. Anti-infection and diagnostic anti-tuberculosis treatment were given at a local hospital without benefit. He returned to our hospital. An ultrasound-guided percutaneous lung biopsy in the left upper lung confirmed the recurrence of MEITL. He underwent three cycles of C-PCT regimen (chidamide plus prednisone, cyclophosphamide, and thalidomide) as rescue therapy. During this time, myelosuppression and pneumonia repeatedly occurred, accompanied by dizziness, fatigue, night sweat, sore throat, cough, sputum, hoarseness, chest tightness, and shortness of breath after exercise. His general condition eventually deteriorated. A CT scan showed that the shadow in the bilateral lungs was aggravating (Figure 3). Enlarged lymph nodes in the mediastinal and right hilar were also slightly larger. On October 20, 15 mo after his diagnosis, the patient decided to quit all treatment. He then left the hospital and died a few days later.

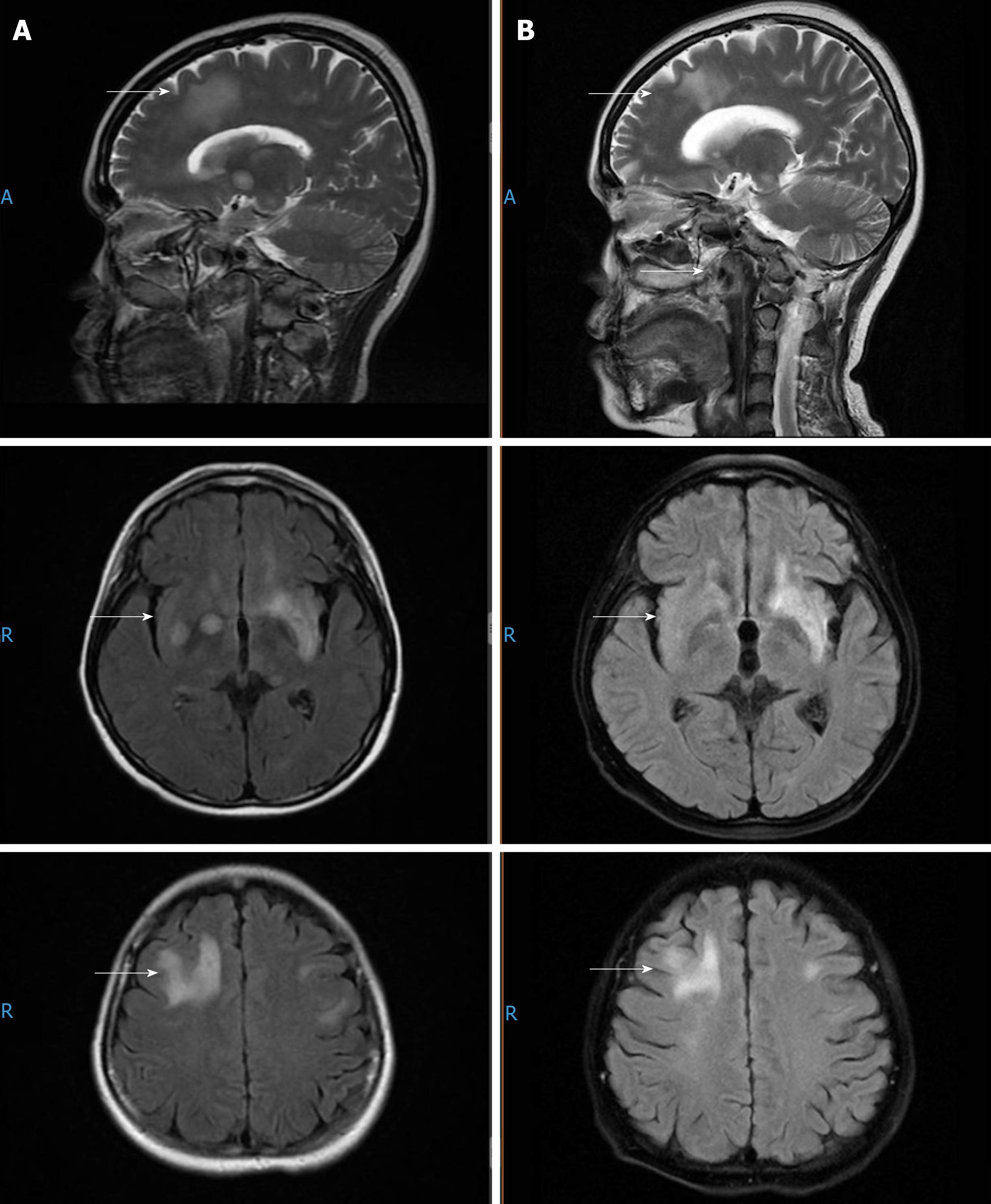

A PET/CT re-evaluation was performed. No hypermetabolic lesion was seen. The efficacy was evaluated as CR. Six months following her diagnosis, she developed diplopia without dizziness, headache, and nausea and vomiting. An enhanced sinus/nasopharynx and head magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed multiple lesions in the bilateral frontotemporal lobes, semioval centers, basal ganglia, insular lobes, left hippocampus, and cerebral foot, which were considered to be lymphoma infiltration. High-dose methotrexate (3.5 g/m2) combined with temozolomide (200 mg d1-3) and chidamide as well as intermittent lumbar puncture and intrathecal injection of methotrexate, cytorabine, and dexamethasone were given as rescue therapy. After two cycles, a head MR evaluation showed that the lesions in the bilateral fronto-parietal temporal lobes, semioval center, basal ganglia, insular lobes, the left hippocampus, and cerebral foot shrank slightly (Figure 4). Unfortunately, afterwards, the lesions aggravated gradually. The patient passed away 17 mo after her diagnosis.

EATL is a kind of rare disease which arises from the intraepithelial T-lymphocytes of intestine[1]. Originally, it was classified into EATL types I and II in the WHO (2008) classification[3]. A better understanding of disease biology led to a change in the terminology. EATL type I is now designated as EATL[1]. It is closely associated with refractory celiac disease, characterized by an allergic reaction to gluten, and associated with human leukocyte antigen class II haplotypes human leukocyte antigen-DQ2 or DQ8[10]. EATL occurs more frequently in areas with a high prevalence of celiac disease, especially in Northern Europe and America[11]. It is rare in East Asian because of the rarity of celiac disease[11]. Although there are many similarities in the clinico-pathological features of EATL and MEITL, some distinct histological, immuno-phenotypical, and molecular markers exist[5]. Histologically, the neoplastic cells of MEITL are mainly monotonous and small to intermediate in size, with round to slightly irregular nuclei, small inconspicuous nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm. The growth pattern is transmural and prone to ulceration, particularly frequent in areas of perforation. The adjacent mucosa contains heavy epitheliotropism without associated inflammatory background. Immunohistochemistry showed activated cytotoxic phenotype including CD3+, CD7+, CD5-, CD4-, CD30-, CD8+, and CD56+. Sometimes, CD8 or CD56 is negative[5].

Due to the tumor location and clinical presentation, many patients (> 80%) need surgical resection at the time of presentation[4,12,13]. Surgery is performed as an emergent procedure in a proportion of patients (> 40%) due to obstruction and/or perforation[12]. According to research, small bowel aggressive B cell lymphoma and T-cell lymphomas are high risk factors contributing to perforation. Patients who had perforation and received emergency surgery had a worse survival[14,15]. In our study, the male patient received resection designedly to remove the tumor, and he presented with recurrence 11 mo after his diagnosis. The female patient was administered an emergent abdominal exploration owing to intestine perforation. Only 6 mo later, bilateral brain recurrence was found.

The course of MEITL is very aggressive. Prior research reported a dismal 5-year survival of approximately 20%[2]. De Baaij et al[9] developed a new prognostic model termed EATL prognostic index (EPI) to distinguish patients into three risk group based on B symptoms and international prognostic index score. The median overall survival was 2, 7, and 34 mo for patients with low, intermediate, and high risk, respectively[9]. In our study, both patients were defined as intermediate risk according to EPI. Historically, after surgical intervention, anthracycline-based regimens including CHOP or CHOPE with or without consolidative autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) was recommended to improve the prognosis[2,4,6,12,16]. However, while anthracycline based regimens led to an overall response rate of 36%-58%, 17%–38% of patients had refractory disease. Most of those subjects relapsed eventually[2,4,12].

High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation was reported to have promising results in a few case reports and small series. In a prospective trial conducted by The Scotland and Newcastle Lymphoma Group[12], 26 EATL patients were treated with induction chemotherapy with a regimen of IVE/MTX (ifosfamide, vincristine, and etoposide, alternated with methotrexate) followed by ASCT. It indicated that the regimen obtained a superior overall response rate with an acceptable safety profile compared to historical controls treated with anthracycline-based regimens (69% vs 42%). The 5-year progression-free survival and overall survival rates were 52% and 60%, respectively. Disease progression, therapy-related side effects, and declining performance status led to failure to complete therapy.

Although an improved survival has been obtained after aggressive consolidation therapy, the true efficacy of those modalities and side effects remain to be identified. Due to comorbidities, performance status, and fragile state of patients following total colectomy, only 50% of patients were reported to be eligible to undergo planned chemotherapy[12]. In our study, the male patient aged 61 years had no special medical history, however, he quitted therapy early due to intolerability of side effects of chemotherapy. This indicated that elderly patients might be unable to endure intensive chemotherapy especially after small bowl resection which can deteriorate the nutrition status.

Development of newer treatment paradigms integrating targeted drugs such as brentuximab vedotin (an anti-CD30 conjugated antibody) is essential to improve outcomes. Khalaf et al[17] reported on a patient with EATL successfully treated with brentuximab vedotin as salvage therapy who had a good response and disease remission at 9 mo of follow-up. Additional case reports using alemtuzumab (a monoclonal antibody against CD52)[18,19] and romidepsin[20] (an HDACI) have shown promising clinical responses.

Chidamide is one of five HDACIs (the other four are belinostat, vorinostat, panobinostat, and romidepsin) which have been approved in China[7]. It showed favorable efficacy in mature T-cell lymphoma in phase I trials[8]. In a phase II trial, an overall response rate of 28% was achieved in 79 patients with relapsed or refractory mature T-cell lymphomas with a median duration of response of 9.9 (1.1–40.8) mo[8].

The patients in our study were both intermediate risk. In order to improve the efficacy of chemotherapy, strategies including chidamide combined with chemotherapy following radical surgery were given. They developed recurrence 11 and 6 mo after the diagnosis and obtained an overall survival of 15 and 17 mo, respectively, which were slightly longer than outcomes in previous studies (7 mo)[9]. This indicated the poor prognosis of this disease entity and chidamide can be used as a novel strategy to improve the prognosis.

Additionally, in our study, the patients were assigned to PET/CT scans to reveal gastrointestinal tumor involvement. The lymphoid cells were metabolically active, as detected in PET/CT, indicating their aggressive characteristics. We recommend PET/CT as a useful tool which can aid early detection and staging of EATL. A previous analysis also showed a higher potential of PET scan to identify EATL compared to CT scan (100% vs 87%)[21].

Pathological examination found no tumor cells in lymph nodes from the peri-intestinal region, suggesting tumor infiltration of the gastrointestinal region specifically. However, recurrence sites of both cases were found to be distant, such as the lung and brain. This implies that the tumor cells disseminate hematogenously, and their metastasis is not prevented by intensive chemotherapy.

In summary, we report two cases of MEITL treated with chidamide combined with chemotherapy with slightly improved survival time. Based on our experience and previous studies, we concluded that the high mortality of MEITL is associated with rapid tumor growth, low chemo-sensitivity, and a tendency to disseminate. The poor condition of patients due to prolonged and severe malnutrition compromises the ability to tolerate chemotherapy. To improve the prognosis, a multimodality treatment approach is suggested in eligible MEITL patients. Surgical de-bulking is preferably the primary step as early as possible followed by subsequent intensive chemotherapy, though the optimal choice of regimen remains to be defined. Consolidation ASCT can be considered in available patients due to its superior outcomes obtained in EATL with the majority of patients lacking marrow infiltration. Novel targeted pharmaceuticals may play a role in this type of lymphoma. However, further investigations are warranted.

We thank Dr. Rong-Ni He for his kind assistance.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bordonaro M S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Choi SM, O'Malley DP. Diagnostically relevant updates to the 2017 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018;37:67-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Delabie J, Holte H, Vose JM, Ullrich F, Jaffe ES, Savage KJ, Connors JM, Rimsza L, Harris NL, Müller-Hermelink K, Rüdiger T, Coiffier B, Gascoyne RD, Berger F, Tobinai K, Au WY, Liang R, Montserrat E, Hochberg EP, Pileri S, Federico M, Nathwani B, Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: clinical and histological findings from the international peripheral T-cell lymphoma project. Blood. 2011;118:148-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphomas: implications for clinical practice and translational research. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009;523-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tse E, Gill H, Loong F, Kim SJ, Ng SB, Tang T, Ko YH, Chng WJ, Lim ST, Kim WS, Kwong YL. Type II enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: a multicenter analysis from the Asia Lymphoma Study Group. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:663-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ondrejka S, Jagadeesh D. Enteropathy-Associated T-Cell Lymphoma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016;11:504-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tan SY, Chuang SS, Tang T, Tan L, Ko YH, Chuah KL, Ng SB, Chng WJ, Gatter K, Loong F, Liu YH, Hosking P, Cheah PL, Teh BT, Tay K, Koh M, Lim ST. Type II EATL (epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma): a neoplasm of intra-epithelial T-cells with predominant CD8αα phenotype. Leukemia. 2013;27:1688-1696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shah RR. Safety and Tolerability of Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitors in Oncology. Drug Saf. 2019;42:235-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chan TS, Tse E, Kwong YL. Chidamide in the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:347-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | de Baaij LR, Berkhof J, van de Water JM, Sieniawski MK, Radersma M, Verbeek WH, Visser OJ, Oudejans JJ, Meijer CJ, Mulder CJ, Lennard AL, Cillessen SA. A New and Validated Clinical Prognostic Model (EPI) for Enteropathy-Associated T-cell Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3013-3019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Green PH, Lebwohl B, Greywoode R. Celiac disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1099-106; quiz 1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chander U, Leeman-Neill RJ, Bhagat G. Pathogenesis of Enteropathy-Associated T Cell Lymphoma. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2018;13:308-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sieniawski M, Angamuthu N, Boyd K, Chasty R, Davies J, Forsyth P, Jack F, Lyons S, Mounter P, Revell P, Proctor SJ, Lennard AL. Evaluation of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma comparing standard therapies with a novel regimen including autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;115:3664-3670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hong YW, Kuo IM, Liu YY, Yeh TS. The role of surgical management in primary small bowel lymphoma: A single-center experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:1886-1893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vaidya R, Witzig TE. Incidence of bowel perforation in gastrointestinal lymphomas by location and histology. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1249-1250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chin CK, Tsang E, Mediwake H, Khair W, Biccler J, Hapgood G, Mollee P, Nizich Z, Joske D, Radeski D, Cull G, Villa D, El-Galaly TC, Cheah CY. Frequency of bowel perforation and impact of bowel rest in aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma with gastrointestinal involvement. Br J Haematol. 2019;184:826-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ellin F, Landström J, Jerkeman M, Relander T. Real-world data on prognostic factors and treatment in peripheral T-cell lymphomas: a study from the Swedish Lymphoma Registry. Blood. 2014;124:1570-1577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Khalaf WF, Caldwell ME, Reddy N. Brentuximab in the treatment of CD30-positive enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11:137-40; quiz 140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gallamini A, Zaja F, Patti C, Billio A, Specchia MR, Tucci A, Levis A, Manna A, Secondo V, Rigacci L, Pinto A, Iannitto E, Zoli V, Torchio P, Pileri S, Tarella C. Alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) and CHOP chemotherapy as first-line treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma: results of a GITIL (Gruppo Italiano Terapie Innovative nei Linfomi) prospective multicenter trial. Blood. 2007;110:2316-2323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Soldini D, Mora O, Cavalli F, Zucca E, Mazzucchelli L. Efficacy of alemtuzumab and gemcitabine in a patient with enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:484-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Piekarz RL, Frye R, Prince HM, Kirschbaum MH, Zain J, Allen SL, Jaffe ES, Ling A, Turner M, Peer CJ, Figg WD, Steinberg SM, Smith S, Joske D, Lewis I, Hutchins L, Craig M, Fojo AT, Wright JJ, Bates SE. Phase 2 trial of romidepsin in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;117:5827-5834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hadithi M, Mallant M, Oudejans J, van Waesberghe JH, Mulder CJ, Comans EF. 18F-FDG PET versus CT for the detection of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma in refractory celiac disease. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1622-1627. [PubMed] |