Published online Mar 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i5.980

Peer-review started: November 26, 2019

First decision: January 7, 2020

Revised: January 16, 2020

Accepted: January 24, 2020

Article in press: January 24, 2020

Published online: March 6, 2020

Processing time: 97 Days and 21.6 Hours

Congenital anomalous retinal artery is rare and does not typically affect visual acuity. However, an abnormal artery that passes through and supplies blood to the macular area complicated with branch retinal artery occlusion may negatively impact visual acuity. This study reports an unusual case of anomalous retinal artery combined with retinal artery occlusion.

A 52-year-old male presented with severely reduced vision in the right eye. The fundus examination revealed an anomalous artery, extending from the superior temporal arcade and crossing the macula into the inferior temporal quadrant. The anomalous artery was partially occluded, with a narrowed lumen. A cherry-red spot was observed with whitening of the macular area, suggesting macular edema. Fundus fluorescein angiography revealed disc leakage and a delayed filling time. Optical coherence tomography revealed increased thickness of the neuroretina and underlying layers. The patient was treated with vessel dilation, hyperbaric oxygen, ocular massage, and thrombolytics. Visual acuity of the right eye subsequently improved to 20/200 from hand motion at 4 cm. This improvement in visual acuity persisted when the patient was examined at the 1-mo follow-up visit. The patient was subsequently followed via telephone interview. The information provided via interview indicated that visual acuity in the affected eye was stable up to 6 years from the time of the initial presentation. However, after 3 additional years, the patient was diagnosed with neovascular glaucoma in the right eye, which was subsequently enucleated.

Although congenital retinal vascular anomaly, including anomalous retinal artery, rarely affects vision, when complicated with branch retinal artery occlusion, the abnormal artery that supplies the macula may severely reduce visual acuity.

Core tip: We report an extremely rare case of retinal vascular anomaly in combination with branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) that led to severe loss of vision in the affected eye. In this case, a large artery branch originated at the superior temporal arcade, and then crossed the horizontal raphe to travel through the macular area. The patient denied all known risk factors for BRAO. The eye with the anomalous retinal artery eventually developed neovascular glaucoma with complete loss of vision. We speculate that the neovascular glaucoma may have been associated with BRAO recurrence.

- Citation: Yang WJ, Yang YN, Cai MG, Xing YQ. Anomalous retinal artery associated with branch retinal artery occlusion and neovascular glaucoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(5): 980-985

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i5/980.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i5.980

Anomalous retinal artery takes various forms, of which a cilioretinal artery is the most common. Other forms, including anomalous course, prepapillary loop, aberrant macular artery, and trifurcation, are unusual[1]. Most patients with retinal artery anomalies are healthy with normal vision[1,2]. However, in rare cases, a congenital anomalous retinal artery has been reported to be associated with macro-aneurysmal rupture[3], central retinal vein occlusion[4], and/or transient vertical monocular hemianopsia[5].

Branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) is a rare condition that accounts for 38% of all cases of acute retinal artery occlusion[6]. No treatment for BRAO has been clinically proven to be effective. Risk factors for this condition include systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, stroke, smoking, and obesity[6].

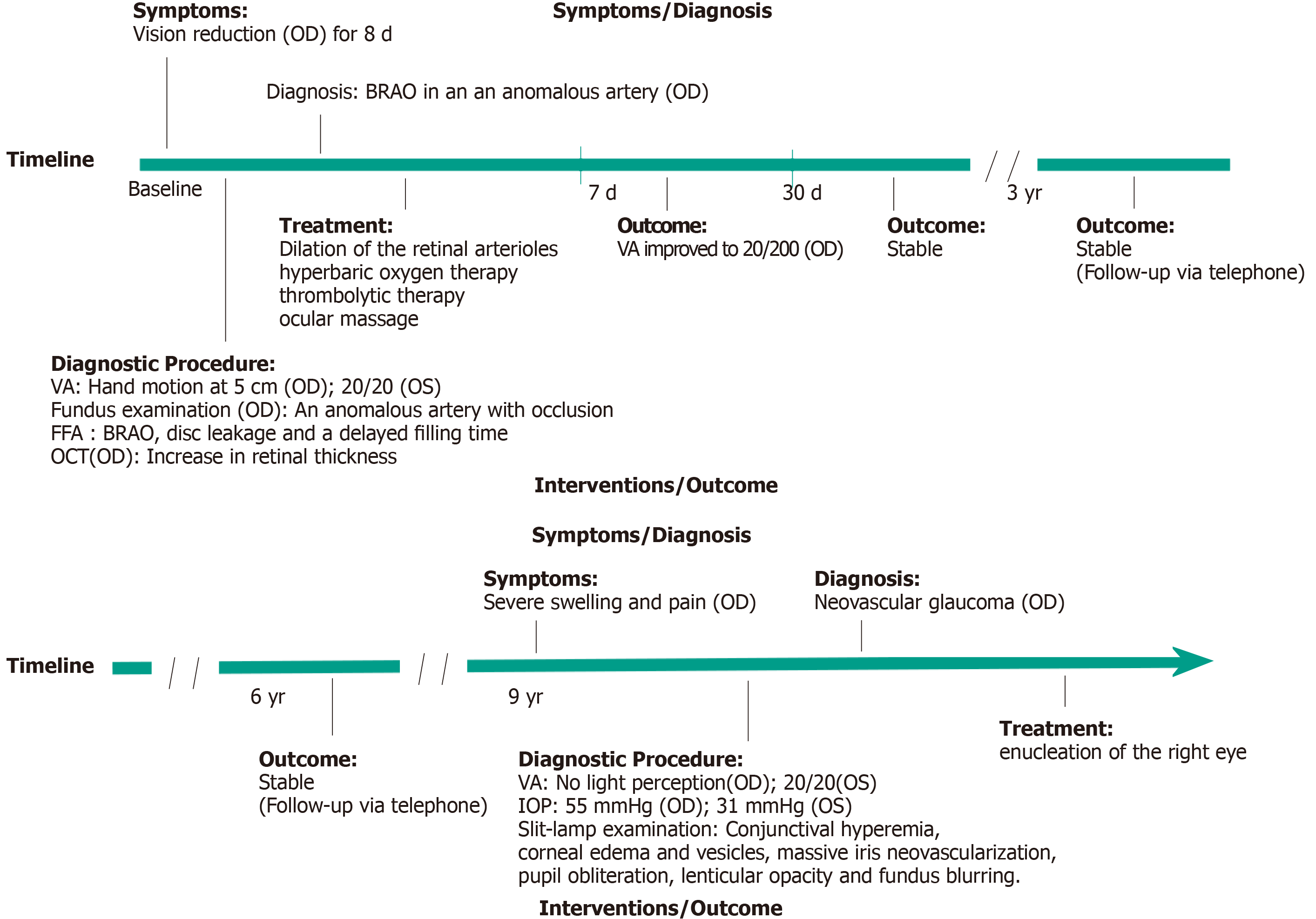

To the best of our knowledge, the association of anomalous retinal artery with BRAO has not previously been reported. In this article, we report a rare case of congenital anomalous retinal artery in which a large retinal artery branch with an abnormal course was associated with BRAO, leading to macular edema and severe loss of vision. The patient eventually developed neovascular glaucoma (NVG) in the affected eye. The clinical timeline is presented in Figure 1.

A 52-year-old male visited our clinic in June 2009 with reduced vision in the right eye for the past 8 d.

No relevant ocular or medical history.

The patient reported no history of systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, stroke, smoking, or obesity.

None.

His visual acuity was hand motion at 5 cm OD and 20/20 OS compared to 20/20 OD and 20/20 OS 8 d earlier. Examination revealed normal findings in the anterior segment and intraocular pressures (IOPs) that were within normal limits in both eyes.

Laboratory examination revealed fasting blood glucose of 4.67 mmol/L, triglyceride of 0.65 mmol/L, total cholesterol of 4.38 mmol/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 6.00 mm/h, and various decreases in whole blood viscosity at low-shear rate, medium-shear rate, and high-shear rate.

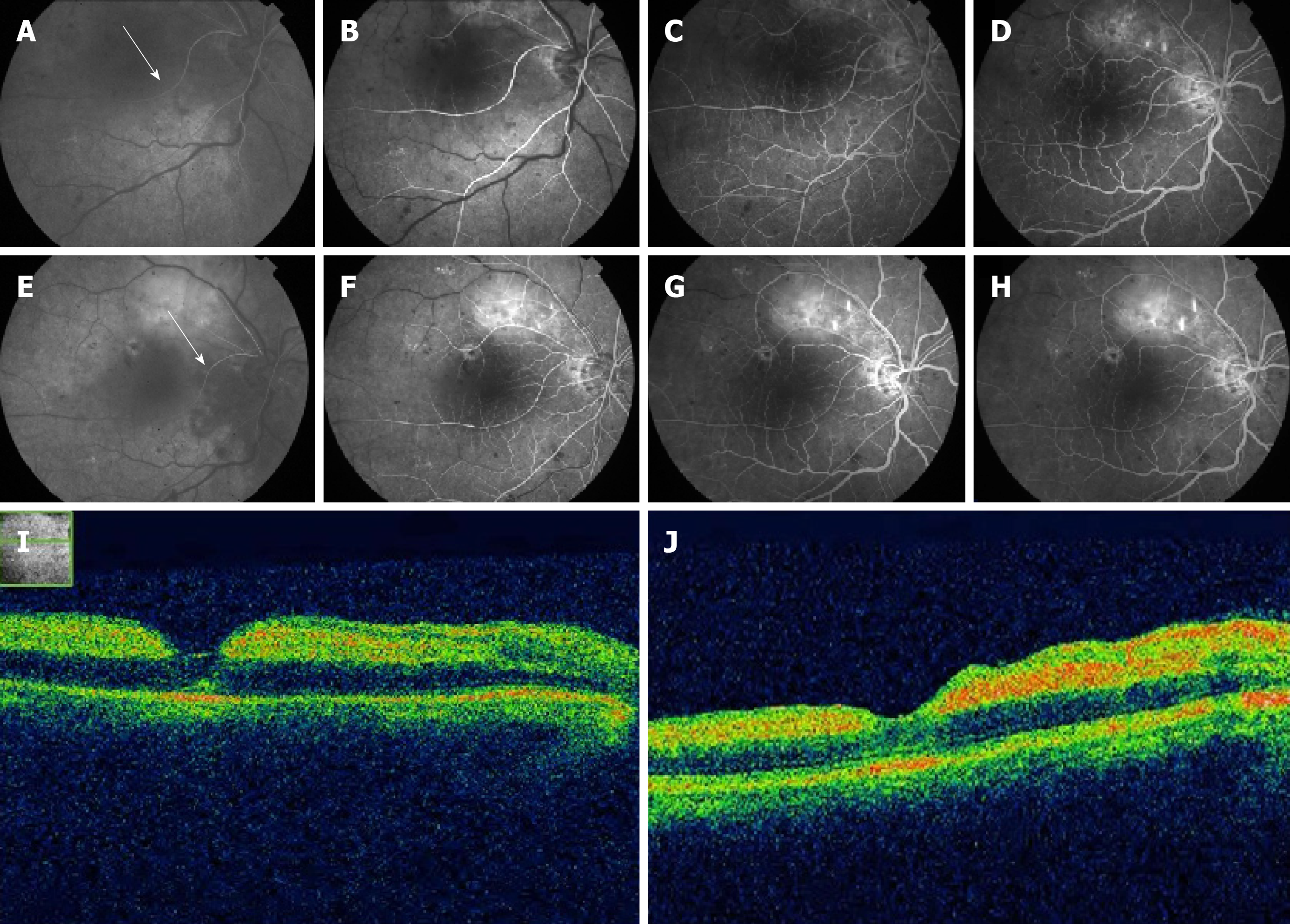

The fundus examination revealed an anomalous artery that extended from the superior temporal arcade, and then crossed the macula into the inferior temporal quadrant. The anomalous artery was partially occluded, with a narrowed lumen. A cherry-red spot and adjacent cloudy whitening indicated an edematous macula (Figure 2). The patient’s pupillary light reflex showed prolonged latency. Carotid ultrasound Doppler suggested mild stenosis of the right vertebro-basilar artery. Fundus fluorescein angiography confirmed involvement of the anomalous inferior temporal artery branch in the BRAO, disc leakage, and a delayed filling time in the right eye (Figure 3A-H). Optical coherence tomography was performed to evaluate these lesions. The results showed increased thickness of the neuroretina and underlying layers (Figure 3I and J).

Anomalous retinal artery associated with BRAO.

The patient was treated with dilation of the retinal arterioles, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and thrombolytic therapy, in combination with ocular massage. At 1 wk later, visual acuity of the right eye had improved to 20/200.

Examination at the 1-mo follow-up visit revealed that this improvement had remained stable. Two subsequent follow-up interviews, conducted via telephone 3 and 6 years later, indicated that visual acuity in the right eye remained unchanged.

At 9 years after initial presentation at our institution (February 2018), the patient was admitted to a local hospital (Yingshan County People’s Hospital, Hubei Province) due to severe swelling and pain in the right eye. Ophthalmic examinations showed that the right eye had no light perception. The left eye’s visual acuity was 20/20. IOP was 55 mmHg in the right eye and 31 mmHg in the left eye. The right eye also showed evidence of conjunctival hyperemia, corneal edema and vesicles, massive iris neovascularization, pupil obliteration, lenticular opacity, and fundus blurring. Based on these findings, the right eye was diagnosed with NVG. The patient subsequently underwent enucleation of the right eye at a local hospital.

We reported an extremely rare case of retinal vascular anomaly in combination with BRAO that led to severe loss of vision of the affected eye. In this case, as is typical for a congenital retinal macrovessel (CRM), a large artery branch originated at the superior temporal arcade, then crossed the horizontal raphe to travel through the macular area. As a form of retinal vascular anomaly, CRM is typically unilateral and rarely affects vision in the affected eye[1,2]. However, the patient may lose vision in the affected eye if the CRM is complicated with a foveal cyst, macular hemorrhage, serous macular detachment, BRAO, or other vascular abnormality[2]. Although CRM typically affect veins[1,2], in this case, the CRM stemmed from an artery.

Although CRMs are typically associated with normal visual acuity, in this case, BRAO of the anomalous retinal artery resulted in dramatically reduced visual acuity (hand motion at 4 cm) at the time of presentation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on an anomalous retinal artery involved in a BRAO. In a similar case previously reported by Goel et al[7], the BRAO was associated with an anomalous retinal vein.

BRAO is not common and may result in a sudden, painless loss of vision. Although the pathogenesis of the BRAO was not determined in this case, the risk factors for BRAO include systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, stroke, and smoking[8]. However, our patient denied all of these factors.

In this case, the superior temporal artery branch took an abnormal course, supplying blood to the inferior temporal, rather than superior temporal, retina. A large survey of anatomical variation, undertaken by Awan[1] included eyes from 2100 people. The inferior temporal retina was supplied by a large branch from the superior temporal artery in 11 eyes, as in the case presented above. The author also reported that the superior temporal retina was supplied by the inferior temporal artery in eight eyes. In such patients, occlusion of the involved artery results in “paradoxical field defects.” Importantly, all patients examined by Awan[1] had normally functioning eyes, despite the abnormal course of the involved artery branches.

In our case, the eye with an anomalous retinal artery eventually developed NVG with complete loss of vision. It has been reported that NVG may result from BRAO[9,10]. Yamamoto et al[9] reported a case of NVG in combination with recurrence of a BRAO 5 wk after a 72-year-old man was initially diagnosed with BRAO. In our case, the NVG appeared 9 years after the initial BRAO. Although the cause of NVG in our case was not determined, we speculate that the NVG may have been associated with a recurrence of the BRAO.

Congenital anomalous retinal artery generally does not affect the vision of a patient. However, an abnormal artery that passes through and supplies blood to the macular area may negatively impact visual acuity when complicated with BRAO.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Meyer CH, Sakina NL S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Awan KJ. Arterial vascular anomalies of the retina. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95:1197-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gülpamuk B, Kaya P, Teke MY. Three Cases of Congenital Retinal Macrovessel, One Coexisting with Cilioretinal Artery. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2018;48:52-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Musadiq M, Gibson JM. Spontaneously resolved macroaneurysm associated with a congenital anomalous retinal artery. Retin Cases Brief Rep. 2010;4:70-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kavoussi SC, Kempton JE, Huang JJ. Central retinal vein occlusion resulting from anomalous retinal vascular anatomy in a 24-year-old man. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:885-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wolpow ER, Lupton RG. Transient vertical monocular hemianopsia with anomalous retinal artery branching. Stroke. 1981;12:691-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hayreh SS. Acute retinal arterial occlusive disorders. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;30:359-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Goel N, Kumar V, Seth A, Ghosh B. Branch retinal artery occlusion associated with congenital retinal macrovessel. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2014;7:96-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Beatty S, Au Eong KG. Acute occlusion of the retinal arteries: current concepts and recent advances in diagnosis and management. J Accid Emerg Med. 2000;17:324-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yamamoto K, Tsujikawa A, Hangai M, Fujihara M, Iwawaki T, Kurimoto Y. Neovascular glaucoma after branch retinal artery occlusion. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005;49:388-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | An TS, Kwon SI. Neovascular glaucoma due to branch retinal vein occlusion combined with branch retinal artery occlusion. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2013;27:64-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |