Published online Mar 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i5.922

Peer-review started: December 3, 2019

First decision: January 7, 2020

Revised: February 4, 2020

Accepted: February 12, 2020

Article in press: February 12, 2020

Published online: March 6, 2020

Processing time: 93 Days and 20.8 Hours

Although few studies have reported hyponatremia due to carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine in patients with epilepsy, no study has investigated cases of carbamazepine- or oxcarbazepine-induced hyponatremia or unsteady gait in patients with neuropathic pain. Herein, we report a case of oxcarbazepine-induced lower leg weakness in a patient with trigeminal neuralgia and summarize the diagnosis, treatment, and changes of clinical symptoms.

A 78-year-old male with a history of lumbar spinal stenosis was admitted to the hospital after he experienced lancinating pain around his right cheek, eyes, and lip, and was diagnosed with trigeminal neuralgia at the right maxillary and mandibular branch. He was prescribed oxcarbazepine (600 mg/d), milnacipran (25 mg/d), and oxycodone/naloxone (20 mg/10 mg/d) for four years. Four years later, the patient experienced symptoms associated with spinal stenosis, including pain in the lower extremities and unsteady gait. His serum sodium level was 127 mmol/L. Assuming oxcarbazepine to be the cause of the hyponatremia, oxcarbazepine administration was put on hold and the patient was switched to topiramate. At subsequent visit, the patient’s serum sodium level had normalized to 143 mmol/L and his unsteady gait had improved.

Oxcarbazepine-induced hyponatremia may cause lower extremity weakness and unsteady gait, which should be differentiated from those caused by spinal stenosis.

Core tip: Unsteady gait is a rare complication of oxcarbazepine; only few cases have been reported and most patients reported in case reports have epilepsy, not neuropathic pain. Oxcarbazepine, along with carbamazepine, is a commonly used drug for the first-line treatment for trigeminal neuralgia. Herein, we report the case of a patient with spinal stenosis who was on long-term oxcarbazepine therapy for trigeminal neuralgia, and manifested symptoms of lower leg weakness as a complication to medication rather than spinal stenosis.

- Citation: Song HG, Nahm FS. Oxcarbazepine for trigeminal neuralgia may induce lower extremity weakness: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(5): 922-927

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i5/922.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i5.922

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a sudden-onset, unilateral condition that causes recurrent pain and affects one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve (i.e., the fifth cranial nerve). According to the American Academy of Neurology and the European Federation of Neurological Societies, the first line of treatment for TN includes carbamazepine (200-1200 mg/d) or oxcarbazepine (600-1800 mg/d). Oxcarbazepine is a keto-analogue of carbamazepine that was developed to bypass the production of the epoxide metabolite of carbamazepine[1-5]. These drugs block voltage-sensitive sodium channels, stabilize the over-excited nerve membranes, and suppress repetitive firing[3,6].

The side effects of oxcarbazepine include drowsiness, nausea, dizziness, ataxia, elevation of serum transaminase, and hyponatremia[1]. Hyponatremia, mild hyponatremia, moderate hyponatremia, and severe hyponatremia are defined as serum sodium levels < 136 mEq/L, between 131 and 135 mEq/L, between 125 and 130 mEq/L, and < 125 mEq/L, respectively[7,8]. Hyponatremia may cause symptoms that are similar to those of spinal stenosis, including lower leg weakness. Therefore, an incisive differential diagnosis between hyponatremia and spinal stenosis is crucial. Although a few studies have reported hyponatremia due to carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine in patients with epilepsy[8], no study has investigated the cases of carbamazepine- or oxcarbazepine-induced hyponatremia or unsteady gait in patients with neuropathic pain.

Herein, we report the case of a patient who presented with symptomatic hyponatremia and lower leg weakness following long-term administration of oxcarbazepine for trigeminal neuralgia. Furthermore, these symptoms could be differentiated from those caused by spinal stenosis.

This case report was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center (IRB number: 20190702/10-2019-51/081). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this article.

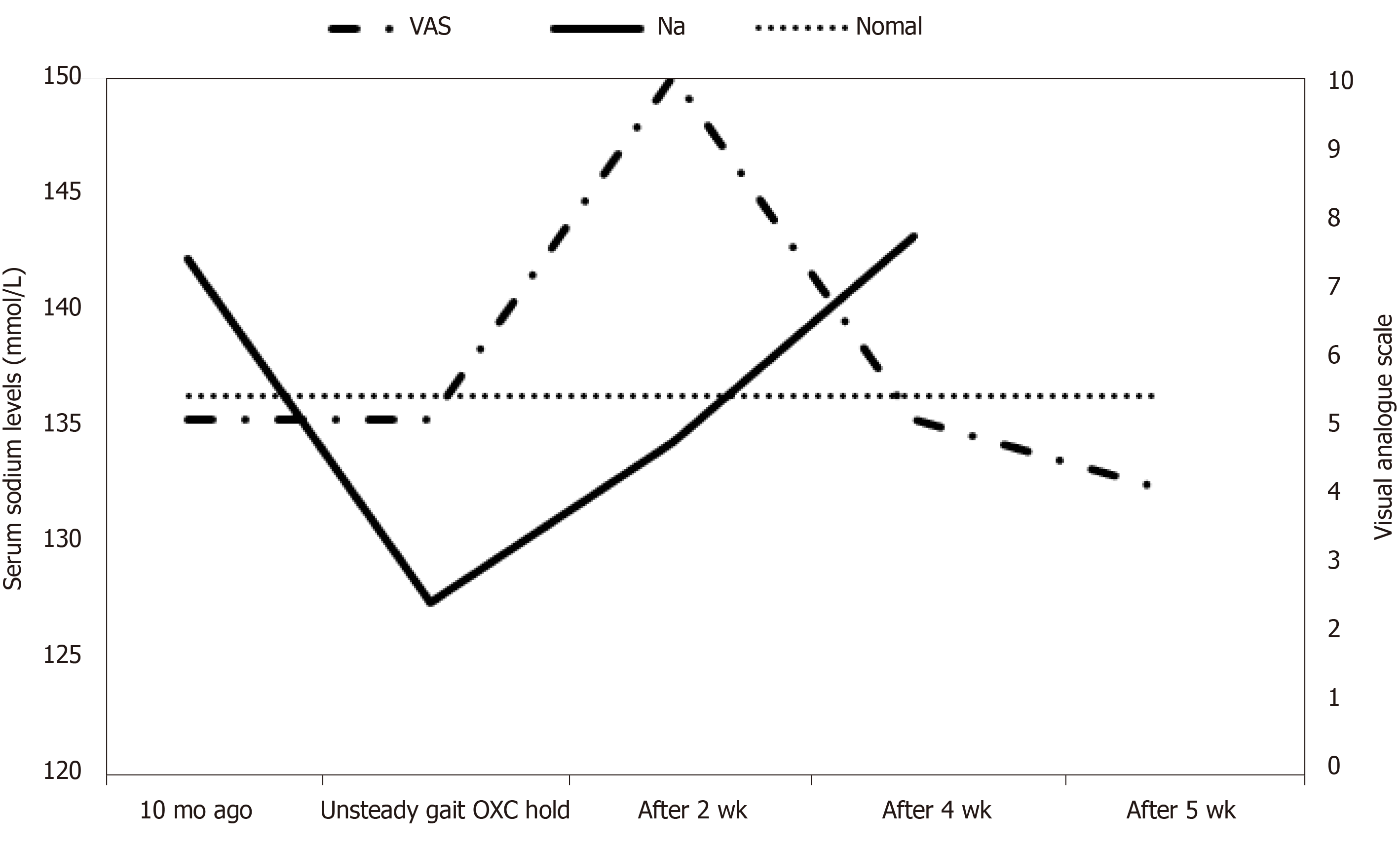

Table 1 shows clinical characteristics of the patient.

| Characteristics | Ten months before OXC discontinuation | Unsteady gait OXC discontinuation | After 2 wk | After 4 wk | After 5 wk |

| VAS | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 4 |

| OXC (mg) | 600 | 600 | |||

| Topiramate (mg) | 75 | 100 | |||

| Na (mmol/L) | 142 | 127 | 134 | 143 | |

| Gait | Several events of fall; the patient required both hand canes and his son’s help to walk | No event of fall; the patient walked alone using both hand canes | The patient walked alone using only one hand cane | Self-ambulation |

A 78-year-old man visited the pain center after experiencing leg weakness and frequent events of fall for several months, and required the use of canes in both hand and his son’s help to walk. The symptom developed 3-4 mo before the current visit. The patient denied neurogenic claudication or cramping pain of the lower extremities.

The patient had visited the hospital five years ago due to severe lancinating pain around his right cheek, eyes, and lip, with pain score of 10 on the visual analogue scale score. The patient was diagnosed with TN involving the right maxillary and mandibular branch and was prescribed carbamazepine (200 mg/d) and gabapentin (600 mg/d) initially. For lack of improvement, the medications were modified several times over a few months, and the patient was finally prescribed oxcarbazepine (600 mg/d), milnacipran (25 mg/d), and oxycodone/naloxone (20 mg/10 mg/d). After taking the medications for less than 2 wk, the patient’s pain improved to a visual analogue scale score of 5. The patient had maintained the medication for 5 years.

Two years ago, the patient experienced occasional back pain and had received the administration of several nerve blocks for a diagnosis of spinal stenosis.

The patient’s hypertension and diabetes were controlled by medications and other vascular risk factors or thyroid diseases were absent.

Physical examinations revealed intact lower extremity motor senses and normal deep tendon reflexes. Rigidity was absent and deep tendon reflexes, including both the knee jerk and ankle jerk reflexes, were normal. On straight leg raise test, the patient could achieve up to 80 and 90 degrees with the right and left leg, respectively. Mild tenderness was found at the lumbar paraspinal muscle area; however, both legs had normal muscle strength.

Results from the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination acquired five years ago in January 2014 during the first diagnosis of TN revealed no abnormalities around the trigeminal nerve; however, an old, small ischemic lesion was indicated near the right pons area, around the trigeminal nucleus. Diffusion images could not obtained during MRI as diffusion sequence was not included in our cranial nerve MRI protocol. A lumbar spine computed tomography scan, performed two years ago in June 2017 as part of radiological examination for back pain, showed multilevel bulging discs at the lumbar spine levels 34 (L3-L4), 4-5 (L4-L5), and 5 (L5), and at the sacral spine level 1 (S1); central canal stenosis at the lumbar spine level 45 (L4-L5); and neural foraminal stenosis at both lumbar spine level 3-4 (L3-L4) and right lumbar spine level 4-5 (L4-L5).

Laboratory exams, including complete blood count and serum electrolyte measurements, were performed to evaluate whether the gait disturbances were due to the side effects of oxcarbazepine. The patient’s sodium level was 127 mmol/L; therefore, he was diagnosed with hyponatremia. Results from other laboratory serum tests (potassium, 4.1 mmol/L; chloride, 89 mmol/L; white blood cell, 9360/µL; Hb, 13.8 g/dL; hematocrit 41.0%; and platelet count, 278000/µL) implied that the unsteady gait was due to moderate hyponatremia. Baseline blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels were 15 and 1.08 mg/dL, respectively.

A diagnosis of symptomatic hyponatremia was made eventually.

Oxcarbazepine was replaced with topiramate (75 mg/d), and further increased to 100 mg/d.

Two weeks after oxcarbazepine discontinuation, serum electrolyte levels were remeasured at subsequent follow-up visit and the patient’s sodium levels had increased from 127 mmol/L to 134 mmol/L; other electrolytes remained at normal levels and his gait improved. Follow-up tests for serum electrolyte levels, 4 wk after oxcarbazepine discontinuation, revealed normalization of sodium levels to 143 mmol/L; other electrolyte levels remained within normal ranges (Figure 1).

This study described a patient who was diagnosed with TN and experienced hyponatremia and subsequent leg weakness following the extended use of oxcarbazepine. Multiple studies have reported hyponatremia due to carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine in patients with epilepsy; however, case reports focusing on oxcarbazepine-induced hyponatremia have only been reported in patients with neuropathic pain, and occasionally include patients with atypical neuropathic pain, but not TN[9]. Additionally, although oxcarbazepine is commonly used for the treatment of TN, no study has been conducted to investigate the adverse effect of this drug in patients with TN.

Hyponatremia occurs in 6%-8% of patients who are prescribed with oxcarbazepine, and alterations in serum sodium levels are associated with the prescribed dose of oxcarbazepine. Patients on high dose oxcarbazepine regimen are more susceptible to hyponatremia and require regular monitoring of serum electrolyte levels. Moreover, patients taking concomitant diuretics are more susceptible to sodium depletion[4].

Findings from a review on carbamazepine- and oxcarbazepine-induced-hyponatremia in patients with epilepsy revealed that hyponatremia occurred in 26% of the patients taking carbamazepine and in 46% of the patients taking oxcarbazepine[10]. The incidence of hyponatremia, which was defined as sodium levels less than 128 mEq/L, were 7% and 22% in the patients who were taking carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, respectively. Symptoms of hyponatremia included dizziness, diplopia, unsteady gait, lethargy, cognitive slowness, tiredness, headache, nausea, and vomiting. Furthermore, about 10 percent of the patients with hyponatremia experienced events of fall and fractures[10]. The risk factors for carbamazepine-induced hyponatremia in patients with epilepsy included age (patients over 40 years of age were at a higher risk of developing carbamazepine-induced hyponatremia than those under 40 years of age); sex (women were at a greater risk of developing carbamazepine-induced hyponatremia than men); menstruation; psychiatric conditions; surgery; psychogenic polydipsia; and the concomitant use of certain medications with a high risk of hyponatremia, including diuretics, opiates, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antiepileptics, antidiabetic drugs, anticancer agents, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs[1]. The risk factors for oxcarbazepine-induced hyponatremia were similar to the those for carbamazepine-induced hyponatremia; however, the risk for the former was more strongly associated with age (i.e., patients over 40 years of age were at a higher risk of developing oxcarbazepine-induced hyponatremia after taking oxcarbazepine than those under 40 years of age, and those over 40 years of age who were taking carbamazepine)[1]. In another study, the dosage of oxcarbazepine was the only significant factor associated with hyponatremia, whereas sex, age, and serum creatinine levels showed no significant association. The cut-off value of oxcarbazepine for the presence of hyponatremia was 1125 mg/d, with a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 70%[11].

This case has a few limitations. First, a lumbar MRI would have provided a more accurate delineation of the back pain and leg weakness. However, the patient was a low-income worker who was covered under the Medical Aid program in South Korea, and therefore, lumbar MRI was refused by the patient because of cost. Second, an electromyography was not performed when leg weakness was present. However, the patient’s symptom did not correlate with physician’s assessment of radiculopathy and the patient was reluctant to undergo a more aggressive work-up because of additional cost. Lastly, the concomitant medication, milnacipran, could have been the etiology, as hyponatremia is a rare adverse effect of the drug. Nevertheless, hyponatremia is more common among consumers of anticonvulsant drugs than in those on antidepressant medications including milnacipran[12]. As both hyponatremia and unsteady gait improved dramatically after discontinuation of oxcarbazepine, we suspected that the effect of milnacipran on hyponatremia was negligible in this case.

This case report describes a case of lower leg weakness and unsteady gait caused by oxcarbazepine prescribed for TN in a patient with spinal stenosis. Patients with TN alone and those with concomitant spinal stenosis frequently visit pain centers. Therefore, gait disturbance due to the side effects of medications may be misdiagnosed as low extremity weakness due to spinal stenosis, and these patients may be referred to surgeons. Physicians at pain clinics should be aware of the side effects of prescribed medications, and carefully monitor and make appropriate changes of medications when necessary to prevent such misdiagnoses.

Overall, our findings demonstrate that routine serum laboratory examinations should be performed for patients with chronic pain and those on long-term treatment with specific pain medications. These patients may require alternative/additional medications because of concomitant underlying diseases, and this may lead to adverse side effects that are caused by interactions between the pain medication and other prescribed medications.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Senol MG, Vagholkar K S-Editor: Tang JZ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Berghuis B, de Haan GJ, van den Broek MP, Sander JW, Lindhout D, Koeleman BP. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and putative genetic basis of carbamazepine- and oxcarbazepine-induced hyponatremia. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:1393-1399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cruccu G. Trigeminal Neuralgia. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2017;23:396-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cruccu G, Truini A. Refractory trigeminal neuralgia. Non-surgical treatment options. CNS Drugs. 2013;27:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Di Stefano G, Truini A, Cruccu G. Current and Innovative Pharmacological Options to Treat Typical and Atypical Trigeminal Neuralgia. Drugs. 2018;78:1433-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Singh S, Verma R, Kumar M, Rastogi V, Bogra J. Experience with conventional radiofrequency thermorhizotomy in patients with failed medical management for trigeminal neuralgia. Korean J Pain. 2014;27:260-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Oomens MA, Forouzanfar T. Pharmaceutical Management of Trigeminal Neuralgia in the Elderly. Drugs Aging. 2015;32:717-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Adrogué HJ, Madias NE. Hyponatremia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1581-1589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1255] [Cited by in RCA: 1106] [Article Influence: 44.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Intravooth T, Staack AM, Juerges K, Stockinger J, Steinhoff BJ. Antiepileptic drugs-induced hyponatremia: Review and analysis of 560 hospitalized patients. Epilepsy Res. 2018;143:7-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Adkoli S. Symptomatic hyponatremia in patients on oxcarbazepine therapy for the treatment of neuropathic pain: two case reports. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2003;17:47-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Berghuis B, van der Palen J, de Haan GJ, Lindhout D, Koeleman BPC, Sander JW; EpiPGX Consortium. Carbamazepine- and oxcarbazepine-induced hyponatremia in people with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2017;58:1227-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lin CH, Lu CH, Wang FJ, Tsai MH, Chang WN, Tsai NW, Lai SL, Tseng YL, Chuang YC. Risk factors of oxcarbazepine-induced hyponatremia in patients with epilepsy. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33:293-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Viramontes TS, Truong H, Linnebur SA. Antidepressant-Induced Hyponatremia in Older Adults. Consult Pharm. 2016;31:139-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |