Published online Mar 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i5.887

Peer-review started: November 19, 2019

First decision: December 23, 2015

Revised: January 19, 2020

Accepted: February 12, 2020

Article in press: February 12, 2020

Published online: March 6, 2020

Processing time: 107 Days and 21.1 Hours

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) may be technically difficult in patients with cavernous transformation of the portal vein (CTPV). Computed tomography (CT) is widely used for assessing the situation of the portal vein and its tributaries before TIPS, and an ultrasound-based Yerdel grading system has been developed, which is deemed useful for liver transplantation. Therefore, we hypothesized that a CT-based CTPV scoring system could be useful for predicting technical and midterm outcomes in TIPS treatment for symptomatic portal cavernoma.

To investigate the clinical significance of a CT-based score model/nomogram for predicting technical success and midterm outcome in TIPS treatment for symptomatic CTPV.

Patients with symptomatic CTPV who had undergone TIPS from January 2010 to June 2017 were retrospectively analysed. The CTPV was graded with a score of 1-4 based on contrast-CT imaging findings of the diseased vessel. Outcome measures were technical success rate, stent patency rate, and midterm survival. Cohen’s kappa statistic, the Kaplan-Meier and log-rank tests, and uni- and multivariable analyses were performed. A nomogram was constructed and verified by calibration and decision curve analysis.

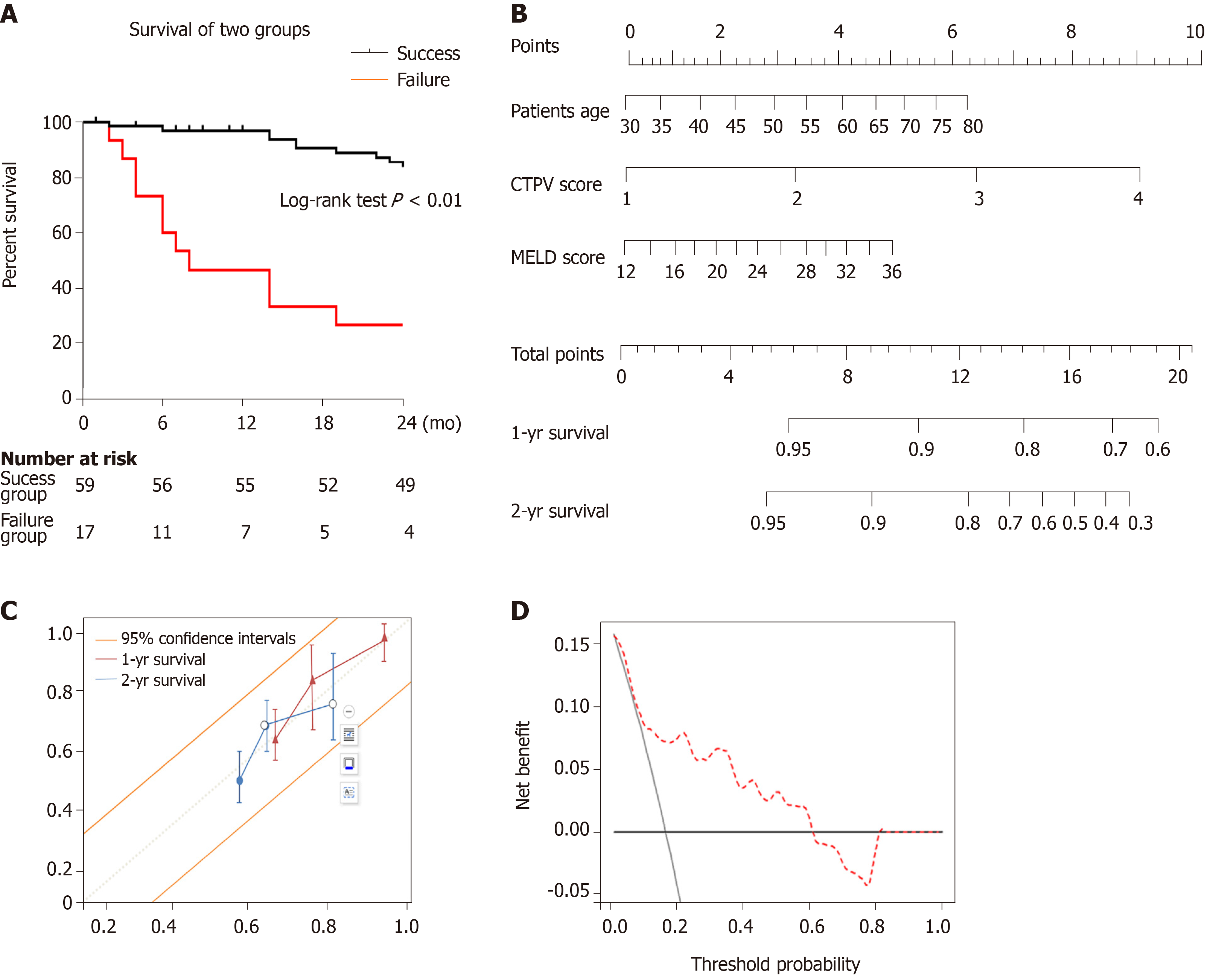

A total of 76 patients (45 men and 31 women; mean age, 52.3 ± 14.7 years) were enrolled in the study. The inter-reader agreement (κ) of the CTPV score was 0.81. TIPS was successfully placed in 78% of patients (59/76). The independent predictor of technical success was CTPV score (odds ratio [OR] = 5.56, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.55-9.67, P = 0.002). The independent predictors of primary TIPS patency were CTPV score and splenectomy (OR = 9.22, 95%CI: 4.78-13.45, P = 0.009; OR = 4.67, 95%CI: 2.59-7.44, P = 0.017). The survival rates differed significantly between the TIPS success and failure groups. The clinical nomogram was made up of patient age, model for end-stage liver disease score, and CTPV score. The calibration curves and decision curve analysis verified the usefulness of the CTPV score-based nomogram for clinical practice.

TIPS should be considered a safe and feasible therapy for patients with symptomatic CTPV. Furthermore, the CT-based score model/nomogram might aid interventional radiologists in therapeutic decision-making.

Core tip: We studied a relatively large cohort of patients with symptomatic cavernous transformation of the portal vein who underwent transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) and found that technical success, stent patency rates, and midterm survival were closely associated with the cavernous transformation of the portal vein score. Compared to patients with TIPS failure, those with technical success had a longer midterm survival. After internal verification, we believe that this simple computed tomography-based score model/nomogram could be useful in decision-making for interventional radiologists, who could perform the TIPS procedure on patients with symptomatic portal cavernoma.

- Citation: Niu XK, Das SK, Wu HL, Chen Y. Computed tomography-based score model/nomogram for predicting technical and midterm outcomes in transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt treatment for symptomatic portal cavernoma. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(5): 887-899

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i5/887.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i5.887

Cavernous transformation of the portal vein (CTPV) refers to a group of interconnected periportal or intrahepatic collateral veins located in the hepatic hilum as a result of long-standing portal vein (PV) thrombosis[1]. This condition can aggravate portal hypertension, which in turn increases the incidence of refractory ascites, variceal bleeding, hypersplenism, etc. Various treatments have been applied for CTPV. Although immediate initiation of low molecular-weight-heparin followed by oral anticoagulant has been advocated, the coexistence of coagulopathy in these patients contradicts its implementation. Expertise on liver transplantation has made it a treatment option in CTPV patients; however, the risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality remains an issue[2].

In previous meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials of patients with cirrhosis, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) creation was found to be effective for the prevention of variceal bleeding and the treatment of refractory ascites[3-5]. A recently published meta-analysis concluded that TIPS is highly feasible and effective for PV thrombosis recanalization, but CTPV is the main determinant of technical failure[6].

Computed tomography (CT) facilitates the development of a liver transplantation strategy by assessing PV occlusion, calcifications, and shunts in CTPV patients[7]. Zhang et al[8] found that the assessment of CTPV by CT portography can aid in precise preoperative decision-making, providing important information. A nomogram is a way to visually demonstrate the results of Cox regression that could be used to predict an outcome of interest for an individual patient[9]. Malinchoc et al[10] reported that a nomogram made up of various clinical data might be useful for predicting patient survival more than 3 mo post-TIPS. However, that study was limited by its short follow-up time, and the research was conducted before the covered-stent era. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop a CT-based model/nomogram that amalgamated the clinical factors for individual preoperative prediction of TIPS treatment for symptomatic CTPV.

This was a single-centre, retrospective study performed in a tertiary care, academic hospital; the study was approved by the local ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to the TIPS procedure. Between January 2010 and June 2017, consecutive patients with symptomatic portal cavernoma who were undergoing TIPS placement at our institution were enrolled in this study. The inclusion criteria were: (1) Intention-to-treat symptomatic CTPV; and (2) Refractory ascites, hepatic hydrothorax, or acute or recurrent variceal bleeding that was unresponsive to medical or endoscopic therapy. The following exclusion criteria were used: (1) Severe cardiopulmonary comorbidity; (2) CTPV after liver transplantation; (3) Prior TIPS; and (4) Liver and other abdominal organ malignancies causing CTPV.

All patients were scanned using multidetector CT (VCT 64; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States). CT was performed using the following parameters: Milliampere-seconds (mAs), automatic; peak kilovoltage (kVp), 120; scan thickness, 5 mm; and gap, 5 mm. The scan protocol included the acquisition of unenhanced images of the upper abdomen, and then the arterial, portal, and delay phases were acquired at 25-30 s, 60-70 s, and 180-240 s, respectively, after contrast injection. Multiplanar reformatting (i.e., axial, corona,l and sagittal images) was done by 1.25-mm collimation.

CT images were retrospectively evaluated by two blinded readers (Niu XK and Wu HL, with 10 and 5 years of experience in reading abdominal imaging, respectively). In general, axial reformatted images are used to determine the CTPV, and reconstructed coronal images are used to record the degree and extent of the thrombus. Based on the literature[7,8] and our own experiences, we adopted the following scoring system to characterize CTPV: A score of 1 was assigned for partial thrombosis of the main PV (MPV); 2 for complete thrombosis of the MPV; 3 for complete thrombosis of the MPV plus thrombosis of the splenic vein or superior mesenteric vein (SMV); and 4 for complete nonvisualization of the MPV or fibrotic cord change of the MPV (Figure 1). The maximum lumen occupancy on CT images was used for analysis.

The TIPS procedure was conducted as previously described[11]. All procedures were performed under local anaesthesia. CT and/or indirect portography were used to evaluate the portal system in each patient prior to the TIPS procedure. In general, a conventional transjugular approach was used to recanalize the occluded PV. When the blinded puncture of the hepatic vein to access the PV failed, either an ultrasound-guided percutaneous transhepatic or transsplenic approach was used depending upon the operator’s discretion. Both the transhepatic and transsplenic tracts were embolized with coils and gelfoam after TIPS. After accessing the PV, a 0.035-inch hydrophilic guide wire was advanced through the occluded portion of the PV until it reached the patent portion of either the MPV, SMV, or splenic vein. Direct portography was performed, and the portal pressure gradient was then measured. Embolization was performed before TIPS creation depending on the number and size of varices. After embolization, an optimally sized balloon catheter was introduced and inflated to optimize the patency of the thrombotic lumen. In case that the MPV thrombotic lumen was still larger than 50%, manual aspiration through an 8-F guiding catheter was performed to maximize vessel patency. To create the shunt, one or two covered stent-grafts (Viatorr/FLUENCY Plus) were then deployed with the proximal end placed at the hepato-caval junction and the distal end in a non-thrombosed portion of the portal system. If necessary, an additional bare metal stent was placed overlapping the previous stent. We also conducted catheter infusion therapy if the patient had a low bleeding risk and relatively unsatisfactory free flow in the MPV. The infusion volume and rate were adjusted based on the individual patient’s coagulation parameters and haemoglobin level. Follow-up portography was undertaken every 24 h. In case that the portography revealed obvious residual thrombus, further intervention (balloon angioplasty and/or manual aspiration) was carried out to ensure the patency of the vessel. Once satisfactory vessel patency was achieved, thrombolytic therapy was stopped. The portosystemic pressure gradient was then measured again to ensure that the target gradient of < 12 mmHg was achieved. During the hospital stay, low-molecular-weight heparin was given routinely at a dose of 5000 IU twice daily for 3 d. Subsequently, anticoagulation therapy with warfarin at a 2.0-3.0 international normalized ratio was maintained for life. Intravenous ornithine-aspartate and branched-chain amino acids were administered for 3-5 d as prophylactics for encephalopathy. Moreover, antibiotics were given for 3-5 d as a prophylactic for operation-related infection. After TIPS, each patient received lactulose (10 mL, two to three times per day) orally for life. In addition, each patient was kept on a low-protein diet.

All patients were followed initially at 3 and 6 mo and every 6 mo thereafter until death or the study closure time (June 2019). Stent dysfunction was assessed by Doppler ultrasound at each visit in all cases. Patients who showed clinical worsening (gastrointestinal bleeding recurrence, black stool, dark-coloured stool, ascites, or severe abdominal pain) or stent dysfunction (suggested by Doppler ultrasound) were subjected to further portography examination and portosystemic pressure gradient measurement. Doppler ultrasound criteria for TIPS dysfunction were: (1) Absent flow in the shunt; (2) Peak intra-shunt blood velocity ≥ 250 cm/s or maximum blood velocity in the portal third of the shunt ≤ 50 cm/s; (3) Maximum PV velocity ≤ two-thirds of the baseline value; and (4) Hepatofugal blood flow inside the portal branches. Shunt dysfunction was defined as shunt stenosis ≥ 50% of the maximum stent lumen and/or portosystemic pressure gradient ≥ 12 mmHg.

TIPS revisions were conducted by the same operator who performed the initial TIPS procedure. The processes included thromboaspiration, local thrombolysis, angioplasty, and even the need for additional stent placement, which was judged by an operator based on his experiences (Figure 2). Finally, hepatic encephalopathy and survival data were also noted for each patient.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 20.0 software (IBM, United States) and R software (version 3.4.2, http://www.R-project.org). Continuous variables are reported as the mean ± SD, and categorical variables are shown as percentages. For comparison of continuous variables, the Welch t test was used, or the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test was used as a nonparametric alternative. The chi-square or Fisher exact test was applied to compare proportions. Cohen’s kappa was used to assess inter-reader agreement. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine factors related to technical success and the TIPS patency rate. Midterm survival between the TIPS success and failure groups was assessed with Kaplan-Meier curves and compared using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards analyses were used to identify factors that predicted patient survival. Based on the results of the multivariate Cox hazard analysis, a nomogram was developed using R software, and the usefulness of the nomogram was evaluated based on the concordance index (C-index). The C-index was calculated to determine its predictive accuracy, and the larger the C-index, the more favourable the accuracy of the prognostic model. Calibration curve analysis was conducted to assess the performance characteristics of the nomogram. Finally, a decision curve analysis was performed. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Overall, our study cohort consisted of 76 patients with a mean age of 52.3 years ± 14.7, and the mean follow-up time was 45.9 mo ± 23.6. The types and incidence of cirrhosis among the patients were as follows: 54 hepatitis B cirrhosis; 5 hepatitis C cirrhosis; 4 alcoholic cirrhosis; 2 autoimmune cirrhosis; and 11 cryptogenic cirrhosis. A total of 64% (49/76) of the patients were identified with Child-Pugh A, 27% (20/76) with Child-Pugh B, and 9% (7/76) with Child-Pugh C liver function (Table 1). The indications for TIPS were as follows: Emergency TIPS for acute variceal bleeding that did not respond to conservative treatment (n = 4), elective TIPS for recurrent variceal bleeding when pharmacologic and endoscopic sclerotherapy failed (n = 50), refractory ascites (n = 9), hepatic hydrothorax (n = 6), and recurrent abdominal pain (n = 7). Liver cirrhosis was confirmed in three patients by liver biopsy, while in the rest combination of prior patients’ history of liver disease, clinical presentation and imaging analysis were deemed sufficient to confirm the diagnosis.

| Parameter | All patients (n = 76) | Success group (n = 59) | Failure group (n = 17) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 52.3 ± 14.7 | 51.1 ± 11.9 | 55.2 ± 17.9 | 0.156 |

| Gender (man/woman) | 45/31 | 35/24 | 10/7 | 0.245 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis (n) | 0.346 | |||

| Hepatitis/non-hepatitis | 64/12 | 52/7 | 12/5 | |

| Manifestation of liver disease (n) | 0.078 | |||

| Varices | 54 | 43 | 11 | |

| Ascites | 9 | 6 | 3 | |

| Hepatic hydrothorax | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| Abdominal pain | 7 | 6 | 1 | |

| Splenectomy (Yes/No) | 12/64 | 8/51 | 4/13 | 0.036 |

| Child-Pugh class A/B/C | 49/20/7 | 39/16/4 | 10/4/3 | 0.136 |

| Child-Pugh score | 6.71 ± 1.44 | 7.18 ± 1.19 | 6.14 ± 1.23 | 0.267 |

| Baseline MELD score | 20.31 ± 14.72 | 19.24 ± 15.23 | 22.46 ± 12.16 | 0.035 |

| Laboratory test | ||||

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 24.10 ± 13.14 | 23.22 ± 15.19 | 26.19 ± 11.33 | 0.216 |

| International normalized ratio | 1.33 ± 0.12 | 1.24 ± 0.11 | 1.34 ± 0.17 | 0.145 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 30.11 ± 5.81 | 29.99 ± 4.85 | 31.44 ± 7.87 | 0.256 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | 5.49 ± 2.12 | 5.26 ± 2.22 | 5.76 ± 2.36 | 0.167 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 66.22 ± 17.17 | 64.30 ± 19.79 | 67.25 ± 17.67 | 0.267 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 132.04 ± 5.33 | 134.41 ± 4.32 | 134.01 ± 7.38 | 0.378 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 13.72 ± 1.95 | 14.48 ± 1.97 | 12.99 ± 1.49 | 0.314 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 93.22 ± 20.53 | 95.12 ± 28.52 | 92.02 ± 17.35 | 0.289 |

| White blood cells (109/L) | 7.05 ± 1.19 | 7.55 ± 1.19 | 6.29 ± 2.48 | 0.179 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 150.12 ± 126.60 | 148.22 ± 119.69 | 154.21 ± 121.61 | 0.089 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 31.42 ± 15.71 | 28.43 ± 17.01 | 32.22 ± 14.08 | 0.067 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 26.34 ± 12.12 | 26.31 ± 13.69 | 27.19 ± 18.76 | 0.261 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 89.56 ± 47.91 | 80.22 ± 54.49 | 90.33 ± 44.19 | 0.213 |

| CTPV score (n) | 0.021 | |||

| 1 score | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| 2 score | 21 | 19 | 2 | |

| 3 score | 34 | 27 | 7 | |

| 4 score | 15 | 6 | 9 |

The inter-reader agreement (κ) of the two readers for the CTPV score was 0.81 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.73-0.86]. Seventy-eight percent (59/76) of the patients had successful TIPS creation. The technical success rate was 100% (6/6) in patients with a CTPV score of 1, 90% (17/19) in patients with a CTPV score of 2, 79% (27/34) in patients with a CTPV score of 3, and 46% (7/15) in patients with a CTPV score of 4. Among the technical success group, 45 underwent the TIPS procedure by the conventional transjugular approach, and 31 underwent the TIPS procedure by a combination of the transhepatic and transsplenic approach. In the technical failure group, all patients underwent conventional TIPS with assistance from the transhepatic/transsplenic approach. As the CTPV score increased, technical success was found to decrease despite increased use of assisted puncture (χ2 = 12.1, Ptrend = 0.031, Figure 3).

Univariate analysis identified the following as predictors of technical success: Ascites (OR = 3.68, 95%CI: 1.51-5.49, P = 0.032), Child-Pugh score (OR = 5.70, 95%CI: 1.78-8.92, P = 0.029), and CTPV score (OR = 7.70, 95%CI: 1.78-13.92, P = 0.012). Multivariable analysis showed that the only independent predictor was CTPV score (OR = 5.56, 95%CI: 3.55-9.67, P = 0.002) (Table 2).

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.16 (0.99-1.35) | 0.123 | ||

| Gender | 2.37 (0.42-5.38) | 0.076 | ||

| Etiology of cirrhosis | 6.16 (0.23-9.22) | 0.065 | ||

| Manifestation of liver disease | ||||

| Varices | 0.97 (0.12-1.78) | 0.068 | ||

| Ascites | 3.68 (1.51-5.49) | 0.032 | ||

| Hepatic hydrothorax | 5.24 (0.45-7.22) | 0.189 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 3.22 (0.12-7.21) | 0.112 | ||

| Splenectomy | 2.22 (0.21-4.36) | 0.156 | ||

| Child-Pugh score | 5.70 (1.78-8.92) | 0.029 | ||

| Baseline MELD score | 4.36 (0.45-8.31) | 0.061 | ||

| CTPV score | 7.70 (1.78-13.92) | 0.012 | 5.56 (3.55-9.67) | 0.002 |

Overall, the primary stent patency rates at 1 and 2 years were 83% and 69%, respectively. The secondary stent patency rates at 1 and 2 years were 89% and 82%, respectively. TIPS correction was performed in 18 patients, of whom 7 had to undergo multiple corrections, 5 had two TIPS corrections, and 2 had three TIPS corrections. TIPS correction included balloon angioplasty (n = 14) and new stent placement combined with balloon angioplasty (n = 4) (Figure 4). In the univariable and multivariable analyses, the independent predictors of primary shunt dysfunction were CTPV score and splenectomy (OR = 9.22, 95%CI: 4.78-13.45, P = 0.009; OR = 4.67, 95%CI: 2.59-7.44, P = 0.017) (Table 3).

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | 3.22 (0.34-6.35) | 0.191 | ||

| Gender | 1.37 (0.33-3.22) | 0.087 | ||

| Etiology of cirrhosis | 7.16 (0.23-11.22) | 0.076 | ||

| Manifestation of liver disease | ||||

| Varices | 2.23 (0.78-4.18) | 0.162 | ||

| Ascites | 2.58 (1.21-6.41) | 0.079 | ||

| Hepatic hydrothorax | 3.14 (0.33-5.22) | 0.198 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 2.22 (0.67-5.21) | 0.134 | ||

| Splenectomy | 1.22 (0.56-3.37) | 0.132 | 4.67 (2.59-7.44) | 0.017 |

| Child-Pugh score | 3.23 (0.89-6.32) | 0.147 | ||

| Baseline MELD score | 2.36 (0.49-5.41) | 0.078 | ||

| CTPV score | 7.70 (1.78-13.92) | 0.012 | 9.22 (4.78-13.45) | 0.009 |

Ten patients expired during the follow-up period post successful TIPS. The causes of death were as follows: Liver/renal failure (n = 2), multiple organ failure (n = 4), refractory hepatic encephalopathy (n = 2), liver carcinoma (n = 1), and massive haematemesis (n = 1). The cumulative survival rates at 12 and 24 mo were 93.7% and 83.0%, respectively. The TIPS procedure failed in 17 patients. Twelve of those patients accepted medical and/or successive endoscopic therapy; nine of them died of multiple-organ failure/uncontrolled massive haematemesis, while the others are currently alive and in follow-up. Five patients underwent surgical devascularization combined with splenectomy. One of them is currently alive, while the others died of multiple organ failure after the surgical procedure. The cumulative mortality rates were significantly different between the success and failure groups (P < 0.01). A Cox regression analysis identified patient age, model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, and CTPV score as independent risk factors (age: HR = 3.62, 95%CI: 1.45-6.76, P = 0.021; MELD: HR = 2.72, 95%CI: 1.27-4.35, P = 0.034; CTPV score: HR = 7.20, 95%CI: 4.43-11.37, P = 0.017). The clinical nomogram is presented in Figure 5. The C-index of the clinical nomogram demonstrated that the survival prediction capability was 0.85 (95%CI: 0.78-0.90). The calibration curve showed that the nomogram predicting 1- and 2-year survival worked well with the constructed model. The decision curve analysis indicated that if the threshold probability is within a range from 0.01 to 0.61, more net benefit is added by using the present nomogram to select the patients who would benefit from TIPS (Figure 5).

Hepatic encephalopathy occurred in a total of 20 patients in the success group. Refractory hepatic encephalopathy occurred in four patients, including one patient who died of progressive hepatic failure. The 1- and 2-year rates of hepatic encephalopathy occurrence were 13.6% and 29.7%, respectively. Hepatic capsule perforation occurred in nine patients (7 of 15 patients with a CTPV score of 4); eight patients accepted medical therapy and recovered well, while one of them was rescued by emergency surgical liver repair. No one died because of major complications in the present study.

Our study demonstrated that TIPS/assisted TIPS is a safe and feasible treatment for patients with symptomatic portal cavernoma. In our study, we achieved a 78% success rate with acceptably low complication rates. Furthermore, our study showed that CTPV score was the only independent predictor of TIPS completion. In our series, multivariable analysis showed that independent predictors were CTPV and splenectomy for TIPS shunt dysfunction. We further developed a nomogram that included patient age, MELD, and CTPV score, which predicted patient survival after TIPS with a higher accuracy (C-index = 0.85).

TIPS insertion has been shown to be effective in lowering portal venous pressure and thus reduce portal hypertensive complications. However, TIPS placement could be technically difficult in patients with CTPV. Only small case series have reported technical and clinical outcomes in such groups of patients[12-23]. The reported technical and 1-year survival rates were 35%-100% and 72%-96%, respectively. Compared to previous studies, our present study mainly had a larger sample size, all patients had covered stent placement, and we had a longer follow-up time.

In PV thrombosis, the most commonly used classification system is the ultrasound-based Yerdel grading system. United States is a non-invasive, rapidly available, and inexpensive imaging technique, but the accuracy of ultrasonography for the diagnosis of CTPV mainly depends on the operator’s experience and could be influenced by inter-operator variability and stage of obstruction[24]. Wang et al[25] reported that 3D DCE-MRA can enhance PV thrombosis diagnosis as well as aid in clinical treatment by depicting the portal system and collateral vessels clearly. However, liver DCE-MRA is susceptible to respiratory motion and has magnetically sensitive artefacts, which limits its use in weak patients with equipment for maintaining vital signs. We investigated a simple CT-based score to predict the outcome of TIPS treatment for patients with CTPV and found that this CTPV score showed overall perfect inter-reader agreement.

The present study demonstrated that CTPV score was the only independent predictor of TIPS completion and may be useful in preoperative assessment. It is noteworthy that the technical success rate when CTPV score 4 was 46% despite the usage of assisted puncture. This suggests that successful stent placement will be ineffective if the PV is unidentifiable or replaced by numerous collateral veins within the portal hilum. Furthermore, 7 of 15 patients with a CTPV score of 4 had hepatic capsule perforation and underwent the TIPS procedure, suggesting relatively high complication rates in this patient group. Therefore, CTPV score can be useful for interventional radiologists in making pre-procedure decisions and being aware of all possible complications in advance.

The present study revealed that primary patency rate at 1 year was 83%, which is relatively higher compared to previous studies. The main reasons for this might be: (1) Usage of covered stents in our research; (2) Routine variceal embolization because it can obviously decrease the rebleeding rates and can supply adequate blood flow into the stent; and (3) Routine usage of anticoagulation therapy except for patients with a high bleeding risk. The rationale behind the usage of anticoagulants in most patients, despite being reported by Wang et al[26] as being necessary for certain patients with PV thrombosis, was based on our belief that continuous use of anticoagulants might preserve stent patency after TIPS surgery. In the multivariable analysis, the independent predictors of stent patency were CTPV score and splenectomy. As the CTPV score increases, the extent of thrombosis in the PV also increases and thus requires longer and multiple stent placement. This might affect the long-term patency of the MPV, especially when more bare stents are deployed depending upon the length of thrombosis. Regarding splenectomy as in previous reports[27,28], we believe that splenectomy before TIPS could decrease PV velocity in the long term and lead to stagnation of the PV or even PV thrombosis, which might be the reason for worsening stent patency in these patients even after TIPS creation.

Our study also demonstrated that the technical success group had a longer survival time than the failure group (P < 0.01), which suggests the overt beneficial effects of TIPS on CTPV patients. So far, there has been no randomized clinical trial or meta-analysis reporting that TIPS could be better than endoscopic therapy for patients with CTPV. Recent research conducted by Li et al[23] reported that TIPS was significantly more effective than endoscopic treatment plus propranolol in preventing rebleeding in cirrhotic patients with CTPV, but without significant survival benefit. However, this study could not be compared directly with our study, as our study included patients with variceal bleeding that was unresponsive to medical or endoscopic therapy. Furthermore, as TIPS is widely accepted as the second-line therapy for symptomatic portal hypertension, we believe that for symptomatic CTPV patients who are refractory to conventional therapy, such as endoscopic haemostasis or diuretic treatment, TIPS could prolong survival. Our present research demonstrated that the independent predictors of survival were patient age, MELD score, and CTPV score. Several grading systems have been developed to identify suitable patients for TIPS[29,30]. Of these, Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score and MELD score are the most commonly used scoring systems. Compared with the empirical CTP score, MELD score calculates a more objective value using laboratory tests to evaluate the severity of liver diseases. In the present study, we found that MELD score outweighed CTP score in predicting middle-term survival. In addition, we identified CTPV score as a new prognostic marker and found that high CTPV score significantly correlated with poor outcome. Therefore, we tried to create a nomogram incorporating the CTPV score and other identified risk factors to predict the 1- and 2-year survival probability of CTPV patients after a successful TIPS procedure. The C-index for the present nomogram was 0.85.

Our study has several limitations. The primary limitation may be the relatively small number of cases, which limited the number of variables that could be simultaneously investigated by multivariate logistic regression and Cox regression analysis. Other limitations include the retrospective design and the single-centre site, which might have led to a lack of generalizability of the results in our study. Finally, we cannot compare TIPS exclusive stents (Viatorr) with covered self-expanding stents (Fluency) because Viatorr stents were not in use until 2015 in China (in the present study, only 11 patients received Viatorr stents).

In summary, our results suggest that clinicians could use this simple grading system to select appropriate patients and therefore maintain a relatively high technical success rate. In addition, the independent predictors of shunt dysfunction are CTPV and splenectomy. Finally, as our CTPV score-based nomogram exhibits a high prognostic predictive value, this nomogram might aid interventional radiologists in therapeutic decision-making and individualized patient counselling.

Cavernous transformation of the portal vein (CTPV) occurs after portal vein thrombosis or intrahepatic venous collateral formation. Sequelae of CTPV can include portal hypertension, splenomegaly, ascites, gastrointestinal varices, obstructive jaundice, mesenteric venous congestion and ischaemia, ascending cholangitis, and biliary cirrhosis. Insertion of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) can reconstruct portal venous flow, reduce portal hypertension, and decrease the incidence of variceal rebleeding. However, the occluded portal vein becomes difficult to access by the transjugular route. Computed tomography (CT) is widely used for assessing the venous situation of the portal vein and its tributaries before TIPS, and an ultrasound-based Yerdel grading system has been developed, which is deemed useful for liver transplantation.

We aimed to investigate a simple CT-based CTPV scoring system that could be useful for predicting technical and midterm outcomes in TIPS treatment for symptomatic portal cavernoma.

Our main purpose was to develop a CT-based model/nomogram that amalgamated the clinical factors for individual preoperative prediction of TIPS treatment for symptomatic CTPV, including technical success rate, stent patency rate, and midterm survival, which might aid interventional radiologists in therapeutic decision-making.

We carried out a retrospective observational single-centre study. A total of 76 patients treated between January 2010 and December 2017 were analysed. The patients were divided into two groups: TIPS success and failure groups. The CTPV was graded with a score of 1-4 based on contrast-CT imaging findings of the portal vein. Outcome measures were technical success rate, stent patency rate, and midterm survival. Cohen’s kappa, the Kaplan-Meier and log-rank tests, and uni- and multivariable analyses were performed. A nomogram was constructed and verified by calibration and decision curve analysis.

The inter-reader agreement (κ) of the two readers for the CTPV score was 0.81. Of note, as the CTPV score increased, technical success was found to decrease despite increased use of assisted puncture (χ2 = 12.1, Ptrend = 0.031). The only independent predictor of TIPS success was CTPV score. The independent predictors of primary shunt dysfunction were CTPV score and splenectomy. The survival rates differed significantly between the TIPS success and failure groups. The clinical nomogram was made up of patient age, model for end-stage liver disease score, and CTPV score. The calibration curves and decision curve analysis verified the usefulness of the CTPV score-based nomogram for clinical practice.

In conclusion, our results suggest that clinicians could use this simple grading system to select appropriate patients and therefore maintain a relatively high technical success rate. In addition, the independent predictors of shunt dysfunction were CTPV and splenectomy. Finally, as our CTPV score-based nomogram exhibits a high prognostic predictive value, we believe that this simple CT-based score model/nomogram could be useful in decision-making for interventional radiologists who could perform the TIPS procedure on patients with symptomatic portal cavernoma.

Further large-scale prospective studies are needed. We will compare TIPS exclusive stents (Viatorr) with covered self-expanding stents (Fluency) in future research.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ali FEM, Di Leo A, Popovic DDJ S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A Wang TQ E-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Kuy S, Dua A, Rieland J, Cronin DC 2nd. Cavernous transformation of the portal vein. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63:529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Loffredo L, Pastori D, Farcomeni A, Violi F. Effects of Anticoagulants in Patients With Cirrhosis and Portal Vein Thrombosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:480-487.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Luca A, D'Amico G, La Galla R, Midiri M, Morabito A, Pagliaro L. TIPS for prevention of recurrent bleeding in patients with cirrhosis: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Radiology. 1999;212:411-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | García-Pagán JC, Caca K, Bureau C, Laleman W, Appenrodt B, Luca A, Abraldes JG, Nevens F, Vinel JP, Mössner J, Bosch J; Early TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt) Cooperative Study Group. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2370-2379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 826] [Cited by in RCA: 842] [Article Influence: 56.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | D'Amico G, Luca A, Morabito A, Miraglia R, D'Amico M. Uncovered transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for refractory ascites: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1282-1293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rodrigues SG, Sixt S, Abraldes JG, De Gottardi A, Klinger C, Bosch J, Baumgartner I, Berzigotti A. Systematic review with meta-analysis: portal vein recanalisation and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for portal vein thrombosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:20-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Brancatelli G, Federle MP, Pealer K, Geller DA. Portal venous thrombosis or sclerosis in liver transplantation candidates: preoperative CT findings and correlation with surgical procedure. Radiology. 2001;220:321-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang LJ, Yang GF, Jiang B, Wen LQ, Shen W, Qi J. Cavernous transformation of portal vein: 16-slice CT portography and correlation with surgical procedure of orthotopic liver transplantation. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:529-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li W, Zhang L, Tian C, Song H, Fang M, Hu C, Zang Y, Cao Y, Dai S, Wang F, Dong D, Wang R, Tian J. Prognostic value of computed tomography radiomics features in patients with gastric cancer following curative resection. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:3079-3089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, Peine CJ, Rank J, ter Borg PC. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 2000;31:864-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1967] [Cited by in RCA: 2067] [Article Influence: 82.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rössle M, Haag K, Ochs A, Sellinger M, Nöldge G, Perarnau JM, Berger E, Blum U, Gabelmann A, Hauenstein K. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt procedure for variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:165-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Senzolo M, Tibbals J, Cholongitas E, Triantos CK, Burroughs AK, Patch D. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for portal vein thrombosis with and without cavernous transformation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:767-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Han G, Qi X, He C, Yin Z, Wang J, Xia J, Yang Z, Bai M, Meng X, Niu J, Wu K, Fan D. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for portal vein thrombosis with symptomatic portal hypertension in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2011;54:78-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fanelli F, Angeloni S, Salvatori FM, Marzano C, Boatta E, Merli M, Rossi P, Attili AF, Ridola L, Cerini F, Riggio O. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt with expanded-polytetrafuoroethylene-covered stents in non-cirrhotic patients with portal cavernoma. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:78-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Perarnau JM, Baju A, D'alteroche L, Viguier J, Ayoub J. Feasibility and long-term evolution of TIPS in cirrhotic patients with portal thrombosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1093-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Luo J, Yan Z, Wang J, Liu Q, Qu X. Endovascular treatment for nonacute symptomatic portal venous thrombosis through intrahepatic portosystemic shunt approach. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:61-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Qi X, Han G, Yin Z, He C, Wang J, Guo W, Niu J, Zhang W, Bai M, Fan D. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for portal cavernoma with symptomatic portal hypertension in non-cirrhotic patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1072-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chen Y, Ye P, Li Y, Ma S, Zhao J, Zeng Q. Percutaneous transhepatic balloon-assisted transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for chronic, totally occluded, portal vein thrombosis with symptomatic portal hypertension: procedure technique, safety, and clinical applications. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:3431-3437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang L, He F, Yue Z, Zhao H, Fan Z, Zhao M, Qiu B, Yao J, Lin Q, Dong X, Liu F. Techniques and long-term effects of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt on liver cirrhosis-related thrombotic total occlusion of main portal vein. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Thornburg B, Desai K, Hickey R, Hohlastos E, Kulik L, Ganger D, Baker T, Abecassis M, Caicedo JC, Ladner D, Fryer J, Riaz A, Lewandowski RJ, Salem R. Pretransplantation Portal Vein Recanalization and Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt Creation for Chronic Portal Vein Thrombosis: Final Analysis of a 61-Patient Cohort. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28:1714-1721.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li ZP, Wang SS, Wang GC, Huang GJ, Cao JQ, Zhang CQ. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for the prevention of recurrent esophageal variceal bleeding in patients with cavernous transformation of portal vein. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2018;17:517-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lv Y, Qi X, He C, Wang Z, Yin Z, Niu J, Guo W, Bai W, Zhang H, Xie H, Yao L, Wang J, Li T, Wang Q, Chen H, Liu H, Wang E, Xia D, Luo B, Li X, Yuan J, Han N, Zhu Y, Xia J, Cai H, Yang Z, Wu K, Fan D, Han G; PVT-TIPS Study Group. Covered TIPS versus endoscopic band ligation plus propranolol for the prevention of variceal rebleeding in cirrhotic patients with portal vein thrombosis: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2018;67:2156-2168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Li LN, Sun XY, Wang GC, Tian XG, Zhang MY, Jiang KT, Zhang CQ. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt prevents rebleeding in cirrhotic patients having cavernous transformation of the portal vein without improving their survival. J Dig Dis. 2019;20:89-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rodrigues SG, Maurer MH, Baumgartner I, De Gottardi A, Berzigotti A. Imaging and minimally invasive endovascular therapy in the management of portal vein thrombosis. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43:1931-1946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang L, Li ZS, Lu JP, Wang F, Liu Q, Tian JM. Cavernous transformation of the portal vein: three-dimensional dynamic contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:463-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wang Z, Jiang MS, Zhang HL, Weng NN, Luo XF, Li X, Yang L. Is Post-TIPS Anticoagulation Therapy Necessary in Patients with Cirrhosis and Portal Vein Thrombosis? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Radiology. 2016;279:943-951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ruiz-Tovar J, Priego P. Portal Vein Thrombosis After Splenic and Pancreatic Surgery. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;906:241-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | de'Angelis N, Abdalla S, Lizzi V, Esposito F, Genova P, Roy L, Galacteros F, Luciani A, Brunetti F. Incidence and predictors of portal and splenic vein thrombosis after pure laparoscopic splenectomy. Surgery. 2017;162:1219-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhang F, Zhuge Y, Zou X, Zhang M, Peng C, Li Z, Wang T. Different scoring systems in predicting survival in Chinese patients with liver cirrhosis undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:853-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gaba RC, Couture PM, Bui JT, Knuttinen MG, Walzer NM, Kallwitz ER, Berkes JL, Cotler SJ. Prognostic capability of different liver disease scoring systems for prediction of early mortality after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:411-420, 420.e1-4; quiz 421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |