Published online Feb 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i4.743

Peer-review started: November 19, 2019

First decision: December 4, 2019

Revised: January 10, 2020

Accepted: January 11, 2020

Article in press: January 11, 2020

Published online: February 26, 2020

Processing time: 99 Days and 9.4 Hours

Dental fluorosis is caused by excessive fluoride ingestion during tooth formation. As a consequence, there is a higher porosity on the enamel surface, which causes an opaque look.

The aim of this study was to identify a dental intervention to improve the smile in patients with tooth fluorosis. Additional aims were to relate the stain size on fluorotic teeth with the effectiveness of stain removal, enamel loss and procedure time using a manual microabrasion technique with 16% hydrochloric acid (HCL).

An experimental study was carried out on 84 fluorotic teeth in 57 adolescent patients, 33 females and 24 males, with moderate to severe fluorosis. The means, standard deviations and percentages were analyzed using nonparametric statistics and ArchiCAD 15 software was used for the variables including stain size and effectiveness of stain removal.

The average enamel loss was 234 µm and was significantly related to the procedure time categorized as 1-4 min and 4.01-6 min, resulting in a P > 0.000. The microabrasion technique using 16% HCL was effective in 90.6% of patients and was applied manually on superficial stains in moderate and severe fluorosis. Procedure time was less than 6 min and enamel loss was within the acceptable range.

Microabrasion is a first-line treatment; however, the clinician should measure the average enamel loss to ensure that it is within the approximate range of 250 µm in order to avoid restorative treatment.

Core tip: This aim of this study was to promote awareness among clinicians and researchers of the use of the proposed minimally invasive technique to treat teeth with enamel fluorosis, to allow recovery of the appearance of natural teeth with 90% efficiency, and an acceptable level of tooth enamel removal. Our results showed that this manual procedure using 16% HCL resulted in a procedure time of less than 6 min, an acceptable loss of enamel (234 µm), and did not require repeated microabrasion.

- Citation: Nevárez-Rascón M, Molina-Frechero N, Adame E, Almeida E, Soto-Barreras U, Gaona E, Nevárez-Rascón A. Effectiveness of a microabrasion technique using 16% HCL with manual application on fluorotic teeth: A series of studies. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(4): 743-756

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i4/743.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i4.743

Dental fluorosis reflects an increment in the enamel surface porosity, causing the tooth to look opaque[1]; the severity and distribution depends on the plasma concentration of fluoride in the amelogenesis stages and host susceptibility[2].

In a recent study by Molina-Frechero et al[3], anti-aesthetic colorations due to dental fluorosis were shown to affect adolescents and their psychosocial relationships. More severe dental fluorosis produces greater aesthetic concerns related to the color of the teeth. Socioeconomic status (SES) plays an important role, as adolescents with a medium SES have less exposure to and less severe dental fluorosis, and thus have fewer dental concerns than low SES adolescents[3]. Accumulating evidence suggests that enamel microabrasion is efficient and effective in producing aesthetic improvements[4-10]. This technique involves minimal enamel loss, leaving a smooth and shiny enamel surface with permanent results[4,5]. The procedure is considered a safe, conservative, atraumatic method for removing superficial enamel stains and defects[4]. Microabrasion was popularized by the research of McCloskey[5] in 1984 and Croll and Cavanaugh[11] in 1986, who used 18% hydrochloric acid (HCL) and named this treatment “Microabrasion of the enamel”. The treatment is considered successful when the stain and/or hypoplasia is removed in conjunction with an insignificant amount of tooth enamel.

The use of the proposed minimally invasive technique to treat teeth with enamel fluorosis allows recovery of the natural tooth appearance[12,13], and markedly decreases the unhealthy whitish enamel. This approach has the advantages of being conservative and well accepted by patients; furthermore, no special maintenance procedures are required, and thus may be considered an interesting alternative to conventional, more aggressive surgical interventions[13]. Microabrasion and dental whitening are two of the most conservative treatments to remove stains caused by dental fluorosis[14,15]. All techniques and bleaching agents used (hydrogen peroxide and carbamide peroxide) are effective and have demonstrated similar behaviors[14]. 10% and 20% carbamide peroxide and 7.5% hydrogen peroxide showed good clinical effectiveness at improving the clinical appearance of teeth affected by dental fluorosis, but it is important to point out that clinical success was obtained only in cases classified as 1-3 using the Total Surface Index of Fluorosis[15]. The dental enamel microabrasion technique is a highly satisfactory, safe and effective procedure[9-13,16,17].

Enamel microabrasion with hydrochloric acid mixed with pumice and other techniques using a commercially available water-soluble paste of hydrochloric acid and fine-grit silicon carbide particles have been described. The successful application of this technique has been studied by researchers for 18 years as a long-term treatment using photographic evidence showing microscopic changes to the enamel surface with significant clinical implications[16]. The microabrasion technique is indicated for the removal of superficial enamel stains, as dental bleaching has proved to be ineffective in solving the aesthetic problem[17,18]. Laboratory and clinical results support the use of enamel microabrasion as the first treatment option for patients with fluorotic teeth, who prefer a less-invasive approach[4,18]. Effective and safe tooth bleaching requires correct diagnosis of the problems associated with tooth discoloration or stains. Furthermore, tooth sensitivity and gingival irritation may occur during the course of bleaching treatment[19,20]. Most of the local effects are dependent on the technique and concentration of the product used[20]. Whitening in healthy adolescents is determined case-by-case and must include the weighing up of risks (oral health and age) against the benefits (improved aesthetic perception)[21]. A study showed that all bleaching materials demonstrated diffusion of peroxide through the dentin in an in vitro pulp chamber device[22]. It has even been reported that peroxide penetration into the pulp chamber of restored and bleached teeth is higher than in intact teeth and therefore causes greater pulp sensitivity[23-26]. The aim of this research was to show the effectiveness of dental fluorosis stain removal treatment in a case series in relation to stain size, procedure time, and enamel loss caused by the treatment, using manually applied 16% HCL microabrasion.

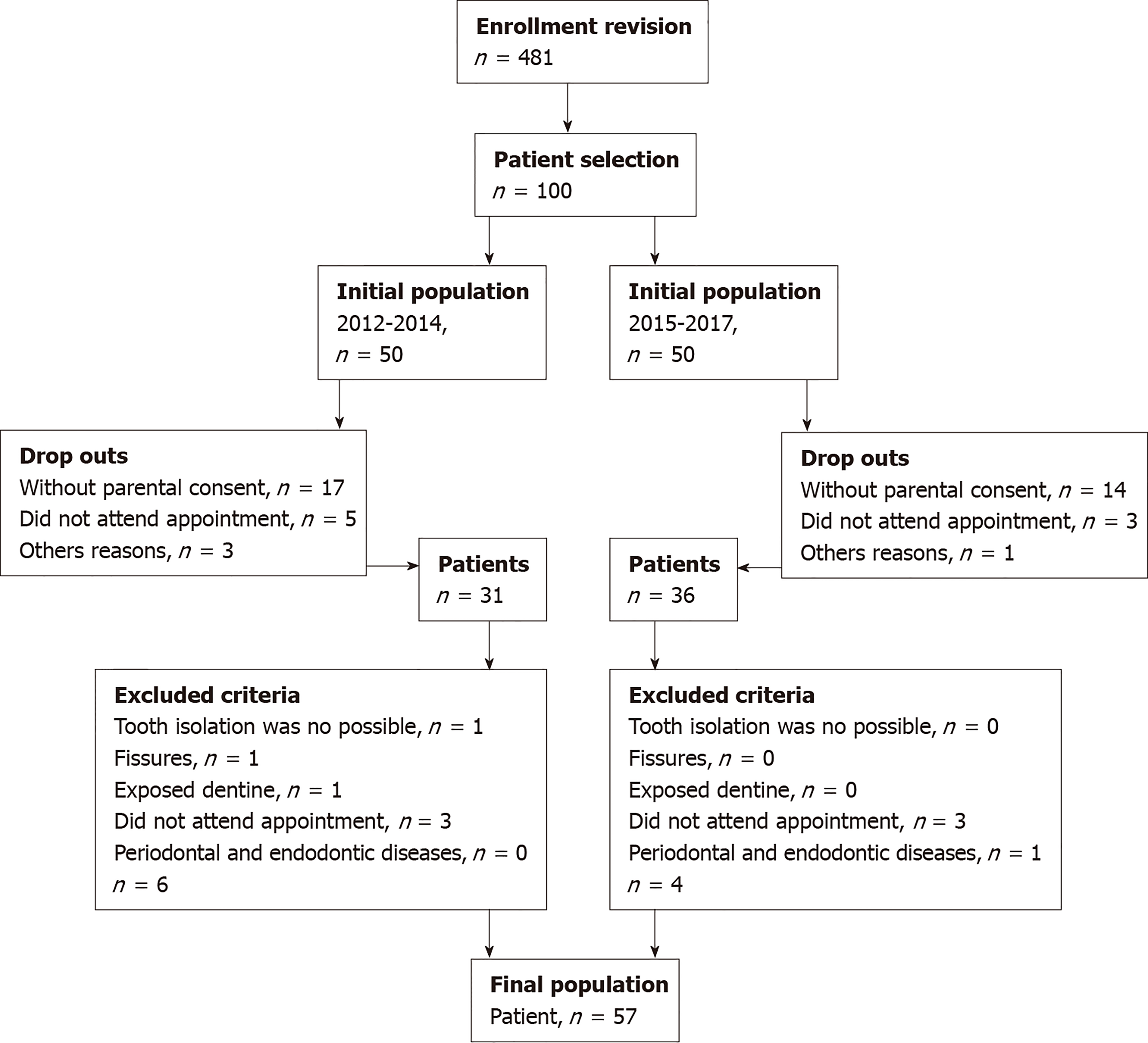

The study protocol was approved by the Facultad de Medicina of the Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua and the Hospital Central Universitario. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to participation (since November 2012). Figure 1 shows a flow chart of patient selection, enrollment, drop outs and final patient numbers.

A cross-sectional experimental study was carried out on 84 central maxillary incisors in 57 adolescents, 33 females and 24 males, whose ages ranged from 12 to 16 years. They were selected from patients attending the Stomatology Clinic at the Autonomous University of Chihuahua, Mexico. Parents of selected children were informed regarding the nature and purpose of the study and an informed consent letter was signed by them.

This research was conducted under the hypothesis that microabrasion treatment is effective in this population. The sample number was not calculated, it was attempted to include a greater number of participants in the study, and that the inclusion criteria were met; the reason for this is that recruiting patients during the study was slow.

The inclusion criteria considered central maxillary incisors with superficial stains on the enamel caused by moderate and severe fluorosis; they were categorized according to the Thylstrup and Fejerskov Index[18]. Diagnostic and radiographic examinations were performed in order to exclude fissures or exposed dentin as well as periodontal and endodontic diseases. Teeth that had not completely erupted were not considered; teeth were deemed not completely erupted when their anatomical crowns were not fully visible, such that rubber dam placement was not possible[27].

The microabrasion technique was performed with 16% HCL (custom chemical made for the study, by REMEKE S. A. de C. V., Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico). Prior to treatment, the teeth were subjected to rubber cup prophylaxis with pumice/water slurry, rinsed thoroughly and dried. Adjacent teeth were isolated and wrapped in ISO TAPE TDV (Star Dental, Costa Rica). The HCL was applied directly with cotton, rubbing the stained area from mesial to distal, for less than 6 min[6,13,16,17,28]. The area was rinsed with water for 1 min. Sodium bicarbonate (ARM and HAMMER, Church and Dwight Company (Ewing NJ, United States)), with water was applied for 1 min[5,16]. After rinsing, a 2% neutral sodium fluoride gel (Euronda Monoart, Vicenza, Italy), was applied for 4 min[5,11,13,16]. The surface of the enamel was then polished at a low speed using diamond polishing paste (Ultradent Products Inc., South Jordan, UT, United States), and the teeth were polished with the resin composite polishing kit Enhance Dentsplay (Ciudad de México). The procedure time was measured in minutes and seconds and was used as a dependent variable. Taking into account that the operator could stop the procedure when, visually, the stain seemed to be removed, the procedure time was also categorized into 2 time levels: short, from 1 to 4 min and long, from 4 min and 01 s to 6 min[13].

Enamel loss was measured in microns (µm), using a clear self-curing acrylic guide on the central maxillary incisors. The guide had an orifice on the lingual surface, and one on the labial surface. Facio-lingual width was measured with a metal calibrator (TBS, Mexico City, Mexico), before and after microabrasion treatment.

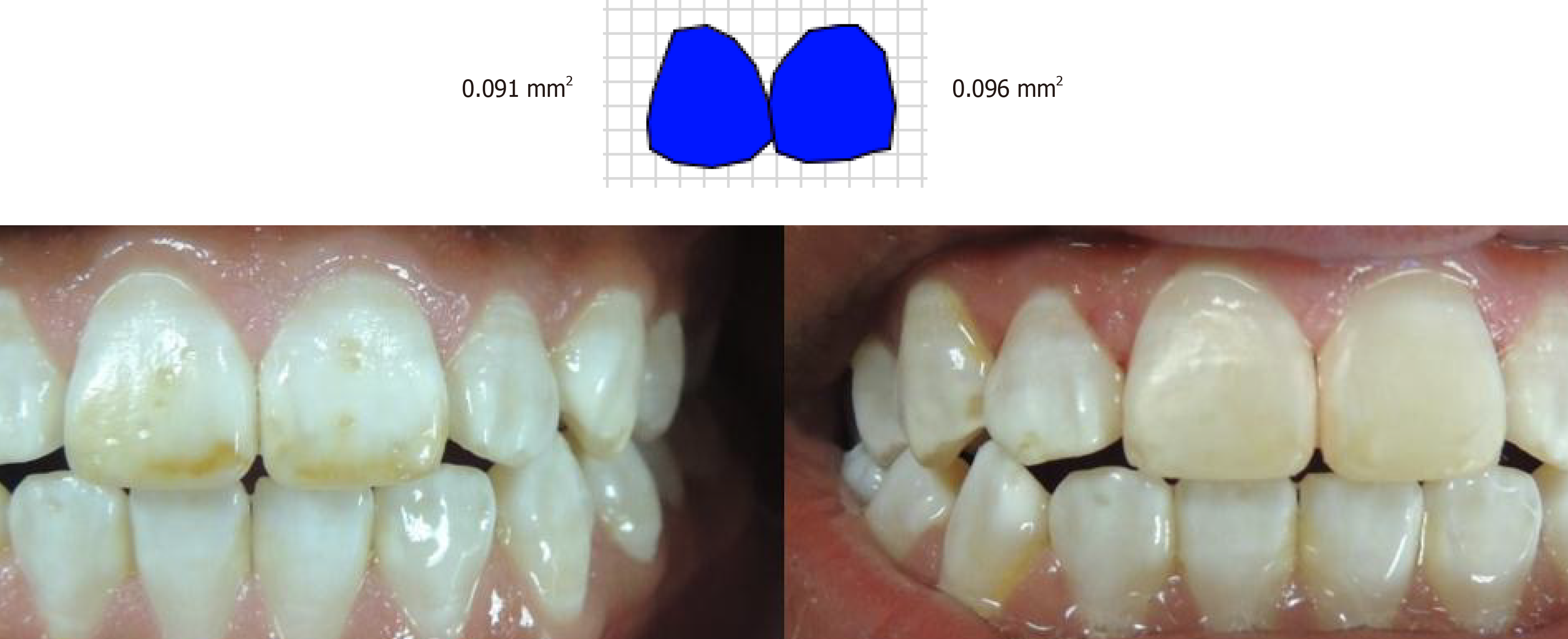

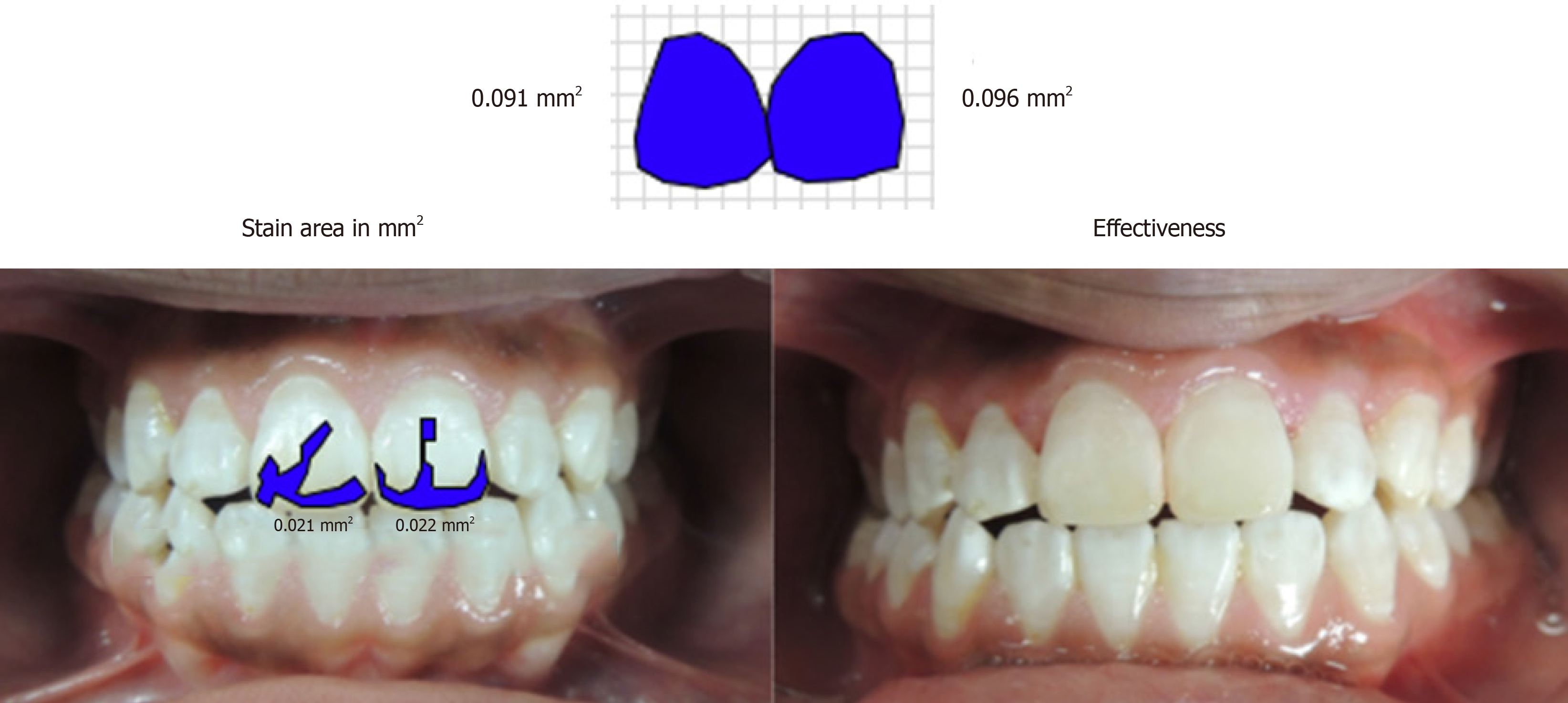

Images of the teeth were taken with a reflex camera Coolpix P510 (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and a standardized distance and angulation before carrying out microabrasion. ArchiCAD 15 image editing software (Graphisoft, Budapest, Hungary), was used to determine stain size in square millimeters (mm2). Stains were categorized into three levels: small stain from 1 to 20.9 mm2, medium-sized stain from 21 mm2 to 40.9 mm2 and large stain from 41 to 67 mm[27-29].

The stain size on the labial surface was measured in mm2 with ArchiCAD software. Treatment effectiveness was determined by the percentage of the residual stain compared to the initial stain.

The variables were analyzed to obtain percentages and distributions. Means and standard deviations were used for quantitative variables. Normality of the data was analyzed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The variables were analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests. The categorical variable of stain size was related to the numeric variables of effectiveness of stain removal, enamel loss and procedure time. In the second stage of the analysis, the enamel loss variable was related to the procedure time variable, and categorized into two levels. Data analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 software for Windows (International Business Machine Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States).

The sample comprised 84 central maxillary incisors in 57 adolescents, 33 females and 24 males, whose ages ranged from 12 to 16 years. The average age was 13 years 11 months for both genders (Table 1).

| Number of patients | Age | Std. deviation | |

| Female | 33 | 13 yr, 11 mo | 1.33 |

| Male | 24 | 13 yr, 11 mo | 0.96 |

| Total | 57 | 13 yr, 11 mo | 1.16 |

The results showed that the mean procedure time was 4 min, with minimum and maximum values of 1.65 and 6 min, respectively (Table 2).

| Minimum | Maximum | mean ± SD | |

| Procedure time in minutes | 1.65 | 6.00 | 3.95 ± 1.43 |

| Valid N (listwise) | |||

All 84 fluorotic central maxillary incisors were treated by the microabrasion technique with 16% HCL applied manually. 24 teeth had a small stain, 42 a medium-sized stain and 18 had a large stain. The mean procedure time for small and medium-sized stains was 3.66 min and 4.08 min, respectively, and for big stains was 4.03 min (Table 3).

| Categorized stain (%) | Procedure time mean (min) | Procedure time (min, s) | n | Std. deviation |

| Small | 3.66’ | 3’40” | 24 | 1.64 |

| Medium-Sized | 4.08’ | 4’05” | 42 | 1.36 |

| Large | 4.03’ | 4’02” | 18 | 1.31 |

| Total | 3.95’ | 3’57” | 84 | 1.43 |

Table 4 shows enamel loss caused by microabrasion treatment. A mean enamel loss of 234 µm was observed, with an increase of 5 µm from small to large stains (Table 4).

| Stain size in mm2 | Mean enamel loss in microns (µm) | n | Std. deviation |

| Small | 234 | 24 | 110.5 |

| Medium-sized | 232 | 42 | 105.2 |

| Large | 239 | 18 | 106.5 |

| Total | 234 | 84 | 105.8 |

No statistical significance was observed for the variables of effectiveness of treatment and categorized stain size P > 0.05 (Table 5).

| Mean effectiveness percentage | |

| χ2 | 4.3 |

| Df | 2 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.117 |

Descriptive statistics showed that both mean and median stain sizes in all groups were similar, which demonstrated that there was no significant difference in stain size between the groups. Mean treatment effectiveness was 90.6%, with similar values in the three stain sizes (Table 6).

| Categorized Stain percentage | Mean | n | Std. deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Median |

| Small | 93.3 | 24 | 14.14 | 52.18 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Medium | 89.2 | 42 | 14.54 | 54.30 | 100.00 | 98.90 |

| Large | 90.5 | 18 | 10.40 | 69.40 | 100.00 | 91.74 |

| Total | 90.6 | 84 | 13.61 | 52.18 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Patients with medium-sized fluorosis stains in tooth 11 had 100% treatment effectiveness following microabrasion (Figures 2 and 3) using ArchiCAD 15 software.

The nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used with the null hypothesis that data were normally distributed, with the alternative hypothesis that data were not normally distributed (P = 0.003). Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected and it was concluded that the data were normally distributed (Table 7).

| Enamel loss in μm | ||

| n | 84 | |

| Normal Parameters1,2 | Mean | 234.05 |

| Std. Deviation | 105.75 | |

| Most Extreme Differences | Absolute | 0.20 |

| Positive | 0.17 | |

| Negative | -0.20 | |

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov Z | 1.81 | |

| Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.003 | |

In light of these results, the Mann-Whitney U test was selected to compare the 2 groups, which was significant, and it was concluded that the 2 groups were different (Table 8).

| Enamel loss in μm | |

| Mann-Whitney U | 440.50 |

| Wilcoxon W | 1665.50 |

| Z | -3.88 |

| Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 |

There were no differences between the means and medians in the groups in terms of procedure time with respect to enamel loss; however, there was a difference of 100 µm. The relationship between enamel loss and procedure time categorized into 2 levels resulted in a mean enamel loss of 196 µm when the procedure time was less than 4 min, and was a mean of 287 µm when the procedure time was greater than 4.01 min (Table 9).

| Enamel loss in μm | ||||||

| Categorized procedure time | Mean | n | Std. deviation | Minimum | Maximum | Median |

| 1 - 4.00 min | 196.12 | 49 | 100.76 | 100 | 450 | 200 |

| 4.01 – 6 min | 287.14 | 35 | 89.4 | 100 | 450 | 300 |

| Total | 234.05 | 84 | 105.75 | 100 | 450 | 225 |

Numerous studies have evaluated the effects of microabrasion, and most of these studies included microscopic evaluations and clinical cases[6,7,29]. The present clinical study evaluated the effectiveness of treatment to remove stains on 84 fluorotic central maxillary incisors, using photographs of the stains before and after microabrasion treatment with 16% HCL, applied manually. ArchiCAD software was used to measure stain size.

The microabrasion technique may be a definitive treatment for teeth with questionable to mild fluorosis stains; therefore, it seems that the degree of satisfaction, which indirectly indicates the effectiveness of the microabrasion procedure, is high when the initial diagnosis of severity falls within certain parameters. The aforementioned authors found that only 65.6% of subjects were satisfied after microabrasion with the PREMA compound (PREMA abrasive paste mixed with 18% HCL). The aesthetic improvements were assessed by the patients and their parents, and their satisfaction level after treatment was recorded[6]. We used a lower concentration of HCL, which was manually applied directly onto the tooth, and we achieved 90.6% effectiveness in removing stains.

Loguercio et al[7], obtained similar effectiveness to that in our study; they evaluated the effectiveness of two microabrasion products for the removal of fluorosis stains. Using a split-mouth study design, two operators used PREMA and Opalustre to remove fluorosis stains in 36 subjects (10-12 years old). Both products were rubbed onto the surface of the affected teeth for 30 s. This procedure was repeated five times during each clinical appointment. A maximum of three clinical appointments were scheduled. The subjects and/or their parents were questioned about their satisfaction with the treatment. Two blinded evaluators assessed both sides of the mouth using a visual scale system. The majority of the subjects (approximately 97%) reported satisfaction at the end of treatment, with a significant improvement in appearance (P = 0.0001)[7].

A study by Train et al[29], utilized a PREMA microabrasion kit, which is a mixture of 15% HCL with pumice, the paste was applied 5 times for 30 s each time, with a maximum of 4 applications. The changes were observed in models and photographs with 10X scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Their results were similar to ours: The effectiveness increased when the stain size decreased, without achieving a statistically significant difference. They compared the effectiveness of the PREMA microabrasion technique in mild, moderate and severe fluorotic teeth. They found that mildly stained teeth achieved the best aesthetic results; moderately stained teeth improved, but showed white stains; severely stained teeth showed a slight improvement[29].

We did not find significant differences in treatment effectiveness between small, medium or large stain sizes; however, effectiveness was greater (3%) in smaller sized stains.

Sinha et al[8], evaluated the effectiveness of 18% HCL and 37% phosphoric acid in an in vivo comparison. Sixty fluorotic permanent central maxillary incisors in 30 patients were divided into 3 categories. The teeth were treated for 5 s (mild fluorosis), 20 s (moderate fluorosis) and 30 s (severe fluorosis). 18% HCL was applied on 11 (right central maxillary incisor), and 37% phosphoric acid on 21 (left central maxillary incisor). Standardized intraoral photographs were taken immediately before, after, and one month after treatment. Vinyl polysiloxane impressions of the teeth were obtained before and after treatment. SEM evaluation was carried out on the models to judge the surface alterations. The results following microabrasion treatment were stable and showed continued improvement over time. The authors also mentioned that the microabrasion procedure was effective in treating mild and moderate fluorosis. The outcome of severe fluorosis treated with microabrasion is unpredictable and there is a need for additional interventional treatment procedures such as resin restorations for aesthetic improvement[8]. We found 90.5% treatment effectiveness for large stains, which is acceptable for improving appearance and avoiding dental restoration.

The study by Celik et al[9], compared the clinical efficacy of enamel microabrasion in the aesthetic management of mild-to-severe dental fluorosis. A total of 154 fluorotic incisors and canines in 14 patients were assessed using visual scale systems. All teeth were treated with enamel microabrasion (Opalustre, Ultradent Products, South Jordan, UT, United States). The severity of fluorosis affected the clinical performance of enamel microabrasion except its performance in removing brown stains. Increased fluorosis severity led to increased requirements for further treatments[9]. Taking into account Celik’s results in severe fluorosis cases, we recommend that the first treatment of choice should be dental microabrasion, and based on the results of treatment effectiveness and enamel loss, a complementary treatment such as whitening or restorations should be chosen.

The study by Price et al[10] showed similar results to ours in terms of treatment effectiveness. These authors evaluated the effectiveness of a microabrasion compound to remove white, yellow and brown stains from the tooth enamel of 32 subjects. Four prosthodontists evaluated the paired images using a standardized questionnaire, with a range from 1 (no improvement in appearance or stain not removed at all) to 7 (exceptional improvement in appearance or stain totally removed). The evaluators found differences between the pretreatment slides and the posttreatment slides; they found no difference between the paired control slides. In all but one subject (97%), the evaluators found that the treated teeth had an improved appearance and a more uniform color. The results of enamel microabrasion showed that use of the PREMA compound was effective in removing stains from the outermost layer of the enamel and in improving the appearance of the teeth[10]; their effectiveness results were high and similar to ours.

All effectiveness evaluation techniques are valid and equally important, in terms of the expectation of aesthetic improvement in the patient, the opinion of relatives, as well as the opinion of professionals; however, the microabrasion technique should not be repeated due to enamel loss, even if the patient’s, the relatives’ or even the dentist’s expectations are not met. In order to repeat the microabrasion technique or to select another treatment, we consider that enamel loss is more important than the patient’s expectations, even when the effectiveness results are not as expected.

We expected greater effectiveness of the microabrasion treatment in teeth treated for 6 min. However, we suggest that when the operator observed the stain had disappeared, they stopped treatment even if the procedure time was less than 6 min; this would have less impact on teeth with lower hardness of dental tissue.

In different microabrasion techniques there are many factors responsible for treatment effectiveness and enamel loss, such as hand pressure, acid concentration, use of rotative instruments and abrasives, and procedure time; another factor is tooth hardness, which is not possible to measure in vivo. However, we must take into account the enamel thickness, which is approximately 1 mm. We considered the results of other studies and the techniques used, and decided to apply a technique with a limited time period.

Clinicians must be aware of the remaining enamel thickness when treating discolored areas. Given that enamel thickness is approximately 1 mm, removal of 0.13 mm may be clinically significant, especially in the long-term, if treatments are repeated. The amount and ease of white stain removal depends on the type of acid and abrasive employed, as well as the application time and pressure[30-32].

Since the initiation of this methodology, the procedure time has been limited to ensure that enamel loss does not exceed 250 µm. For that reason it was decided to stop the procedure before reaching 6 min, or when the operator observed the stain had disappeared; indeed in some cases the stain required less time for removal with high treatment effectiveness, similarly in other cases the treatment was stopped before 6 min and treatment effectiveness was not 100%; this was considered an error; however, the operator had the opportunity to consider the necessary procedure time depending on the hardness of the teeth.

The results of the study by Dalzell et al[30] were similar to our findings. Their investigation included various procedure times, number of applications, and pressure applied individually and in combination. Twenty-seven extracted premolars were hand-rubbed with an 18% HCL-pumice mixture at time intervals of 5, 10, and 20 s and 5, 10, and 15 applications under pressures of 10, 20, and 30 g. Enamel loss significantly increased as each variable increased, respectively. When two variables increased at the same time, a greater amount of enamel loss occurred than when one variable increased. The combination of ten 10-s applications or 15 5-s applications with 20 g pressure resulted in enamel loss slightly less than 250 µm[30]. Their results matched those obtained in our study, with an average enamel loss of 234 µm, which is considered acceptable.

Waggoner et al[31] in 1989 used a measuring microscope which was an effective method of measuring enamel loss. The serial rubbing application of a mixture of 18% HCL and pumice initially removed an average of 12 µm of enamel, with 26 µm removed with each subsequent application. A series of 10 applications removed enough enamel to account for approximately 25% of the labial enamel in permanent incisors. The sum of enamel loss following all applications was higher than the average in our study (234 μm), because they used a higher concentration of HCL and repeated pumice stone applications. It would seem that interrupting the application of microabrasion decreases HCL contact and consequently enamel loss; however, time in contact with the acid is apparently cumulative. Thus, we believe that there is more control when you have a continuous and established procedure time.

According to one study, in-office bleaching and enamel microabrasion techniques were performed on extracted teeth to investigate their microscopic effects on the surface enamel. Tong et al[32] used direct application of 18% HCL for 100 s which resulted in enamel loss of 100 ± 47 µm. The extent of enamel loss was much greater when 18% HCL was applied in a pumice slurry for the same period of time (360 + 130 µm), and the effect was time-dependent. Thus, the pumice and rotary prophy cup used in conjunction with 18% HCL markedly contributed to surface enamel loss, and enhanced the non-selective stain removing action of HCL. Therefore, the HCL-pumice technique must be used with caution. The reported enamel loss using 18% HCL was smaller than that in our study; this was because the sample taken by Tong et al[32] did not have dental fluorosis.

When pumice was used in the microabrasion technique, the enamel loss increased from 100 to 360 μm[32]. In our study, HCL application was direct and manual, only an impregnated cotton ball without pumice was used and as a result the enamel loss was within the acceptable range (234 μm), without the need for restorative treatments[31].

The combination of tooth whitening and microabrasion should take into account the decrease in enamel thickness[30,31,33], as younger patients will have greater permeability of enamel and dentin towards the pulp[19,22], since most of the local effects depend on the technique, concentration and procedure time[20]. The use of enamel whitening should be limited to use only in patients for whom such treatment is professionally justified and should not be recommended for cosmetic adjustment of tooth color just to comply with the demand of the patient. Furthermore, risk assessment has shown that the minimum acceptable safety factors might not be attained in certain clinical situations[34].

An advantage of microabrasion over tooth whitening is that HCL only etches the surface of the enamel, but does not increase the permeability of the enamel and dentin[35].

Some studies have shown that when microabrasion is performed manually, less enamel loss occurs compared to mechanical microabrasion with rotary instruments[16,17,32,36]. Microabrasion techniques that use pumice significantly increase enamel loss[7,10,16,32].

The procedure time is one of the main variables in the success of enamel microabrasion, and can be reflected both in stain removal effectiveness, as in enamel loss and the need for restorations. In our study, the procedure time, which was limited to 5 min, had a significant relationship (P = 0.015) to the wear caused by microabrasion treatment, with an average enamel loss of 234 μm, which is in the acceptable wear range[13], and within 25% of the labial enamel[31,34].

We consider that several sessions to complete dental microabrasion can result in the necessity for resin placement or veneer restorations. According to our results, repetition of microabrasion is not recommended[6,7,29]. With regard to patient safety, the total procedure time for any microabrasion technique should be registered if several applications are made; it is also recommended that enamel loss should be registered using the technique described in this study, which is easy to implement in the clinic.

Technical variables, such as application force, type of abrasion (mechanical or manual) and duration of the procedure, can directly affect the amount of tissue removed[37]; in the present study, the average procedure time of 4 min resulted in removal of the stain from the enamel surface with 90.6% effectiveness. Therefore, 16% HCL with a maximum procedure time of 4 min was acceptable and constitutes a safe and conservative treatment with greater control of enamel loss, with the possibility of having a shiny surface that could subsequently be remineralized naturally by saliva[38] or by fluoride application, ultimately avoiding the use of restorations.

This study evaluated the effectiveness of microabrasion to remove stains in fluorotic enamel; therefore, color was not taken into account but rather stain size. Regarding the classification of fluorotic teeth, the defect color does not provide additional information on the cause of the anomaly, given that the enamel may be so porous (or hypomineralized) that the outer enamel breaks apart post-eruptively and the exposed porous subsurface enamel becomes discolored[1,2,18].

Some considerations must be taken into account when planning microabrasion treatment, for example, whether the patient has undergone or planning restoration treatment, as rough surfaces can be eroded when conducting microabrasion, resulting in enamel removal due to the rebonding strength of the resin composite, the bond strength of enamel and restorative materials, and the bonding of metal attachments to sandblasted porcelain and zirconia orthodontic brackets[39].

The immediate or late combination of dental bleaching with enamel microabrasion did not negatively influence the surface roughness or hardness of the enamel[40], and the sensibility of the patient must be taken into account after dental bleaching[19,26]. There is evidence that microabrasion and bleaching treatments produce significant changes in enamel roughness and microhardness, such as an increase in microhardness after microabrasion and a decrease in hardness after home bleaching treatment[41]. When using a combination of microabrasion with dental bleaching, a remineralization treatment may be added to reduce sensibility and promote enamel structure repair[42].

If planning to fix resin restorations on teeth that will receive microabrasion treatment, it is recommended to wait more than 24 h, as enamel repair after contact with liquid acid commences within 2 h following an acidic treatment and is completed 4–24 h later[43].

Patients should be warned that exposure to acidic and alcoholic drinks alters the roughness of dental restorations; therefore, diet modifications and improved oral hygiene are essential in order not to damage the bonding strength of the teeth and restorations, especially if they previously received microabrasion treatment; moreover, as the surface characteristics are strictly related to bond strength, the adhesion of orthodontic, conservative and prosthodontic frameworks also need to be carefully considered for microabraded enamel surfaces[44].

Home dental bleaching success goes hand in hand with patient cooperation; a TheraMon microsensor embedded in a custom acetate tray can also be used, enabling measurement of the degree of patient compliance during treatment[45].

However, this technique has been performed extensively, and represents a highly satisfactory, safe and effective procedure[4-14,16,18,28-32,35-38,40-42,45].

One of the limitations of this study is the delicate nature of the technique, starting with placement of the rubber dam. Perfect marginal adaptation must be achieved to avoid soft tissue damage. The technique for enamel loss measurement can also be difficult; if the metal calibrator is not positioned in the same place, measurement errors can occur. On the other hand, the pressure exercised by the operator and procedure time may vary and they may accelerate enamel loss; these are the reason for the variation in procedure time in this study. Another operator-dependent factor is stain removal; this criterion can be subjective, as our results showed that short procedure times were not enough to remove the stain completely.

According to our results, we can conclude that manual microabrasion treatment using 16% HCL and a procedure time of 6 min was 90.6% effective in removing stains on fluorotic teeth. Enamel loss caused by manual microabrasion was within the acceptable range, with an average of 234 μm. There was significantly higher enamel loss when the procedure time was greater than 4 min. The stain size was not significant in terms of enamel loss, procedure time or effectiveness. In cases where microabrasion did not completely remove the stain, it is not recommended to repeat the technique; a whitening treatment is preferred in such cases, taking the patient’s enamel loss and characteristics into account.

In Mexico, dental fluorosis is considered a common health issue, especially in desertic areas, due to the high mineral content in water from increasingly deeper underground wells. In the State of Chihuahua there is an increasing number of individuals affected by fluorotic enamel stains, which are conspicuous and affect socialization of young people, and the majority of young people have some degree of dental fluorosis. Our main objective is to help society through research and for that reason our efforts have been directed at trying to provide a safe and effective treatment for dental fluorosis. Despite conducting several clinical studies, we have not previously published our results. However, we believe that our experience could help improve or set new guidelines for the treatment of dental fluorosis.

One of the main problems of fluorosis treatment in children and adolescents is the selection of first-choice treatment, which often is restorative instead of whitening or microabrasion and later must be periodically changed. Thus, it is important to implement non-invasive treatment protocols for young individuals with stains which compromise their aesthetic appearance. On the other hand, there are many microabrasion techniques with variations in the materials and procedures used, which we could unify to achieve an ideal treatment, through research of these variables. One of the main motivations for this research was the differences observed between a manual technique and a mechanical technique; therefore, we decided to use a manual technique, improve it and then compare it against a technique using rotary instruments. Thus, the choice of technique could become clearer following improvement, which may involve the unification of criteria and techniques.

One of the main objectives of this study was to assess the effectiveness of the microabrasion technique by taking into account enamel loss caused by the technique against the benefit of stain removal. In addition, the variation in procedure time taking into account stain size was estimated. These variables were measured using simple techniques that can be carried out by any dentist, except for the assessment of treatment effectiveness, which was measured using initial and final images and specific software. Measurement of these variables can be performed in any dental microabrasion technique, and the outcome of several techniques can be compared. However, we believe that the manual microabrasion technique is less invasive than those techniques involving rotary instruments, which we attempted to show in this study.

Dental fluorosis is a line of research that we have developed for many years in the Autonomous University of Chihuahua. Before this study, we conducted other projects which showed the advantages and disadvantages of microabrasion. Through time we have experimented with different methodologies from patient selection, to the technique itself. We conducted a study comparing the manual and rotary techniques, where stain measurement and efficiency were carried out using geometric figures and determined the surface area using photographs with a ruler on the patient’s chin. Procedure time could be extended and it was especially difficult to measure using rotary instruments, as several applications were made and it was difficult to measure the total procedure time. It took some time to design the acrylic guide to measure enamel loss, as there were several orifices around the stain and we averaged the results. We soon realized that this method was not reliable and we changed and perfected the technique. We observed that when microabrasion was completed there were occasional diastemas in adjacent teeth and we decided to protect these teeth. We believe that we must continue to improve and propose alternatives for measurement, through our results and through publishing in order to receive expert opinions.

One of our main findings in this study is the effectiveness of this technique, which was on average 90% despite the stain size in the fluorotic enamel and variations in procedure time. We consider that it is a safe and minimally invasive treatment, as the manual technique provides greater control of enamel loss, which was shown to be within 250 μm; therefore, it is a safe and conservative treatment. Of the safety measures, procedure time is directly related to enamel loss in any microabrasion technique; therefore, it was limited to 6 min; in addition to this, in teeth where the stain was removed before this time, it could be reduced to 1.65 min.

The effectiveness of this technique was on average high at 90%; however, we did not observe statistical significance with respect to stain size, enamel loss and procedure time, but we did find an upward trend. Procedure time and enamel loss were lower in small stains, but were not significantly different in middle-sized and large stains. The highest enamel loss occurred in large enamel stains, or those over 40% of the vestibular face, but without statistical significance. Enamel loss was statistically significant when the procedure time was more than 4 min, with an average of 234 μm; however, the minimum and maximum values reached 100 and 450 μm, for a procedure time under and over 4 min, respectively. Controlling the procedure time to under 6 min using 16% HCL and the manual technique resulted in enamel loss within the acceptable average range. Reduction in the size of the enamel stain caused by fluorosis after microabrasion was related to the tooth surface percentage covered by the stain.

Mechanical microabrasion techniques using abrasives result in greater loss of fluorotic enamel than manual microabrasion techniques without abrasives. The effectiveness of the microabrasion technique using software is different than the effectiveness perceived by the patient and their relatives.

This study received the statistical advice of PhD Jorge Alfonso Jiménez Castro and language review services of Ivan Rodriguez.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Andrea S, Paredes-Vieyra JP S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Webster JR E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Fejerskov O, Manji F, Baelum V. The nature and mechanisms of dental fluorosis in man. J Dent Res. 1990;69 Spec No:692-700; discussion 721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fejerskov O, Larsen MJ, Richards A, Baelum V. Dental tissue effects of fluoride. Adv Dent Res. 1994;8:15-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Molina-Frechero N, Nevarez-Rascón M, Nevarez-Rascón A, González-González R, Irigoyen-Camacho ME, Sánchez-Pérez L, López-Verdin S, Bologna-Molina R. Impact of Dental Fluorosis, Socioeconomic Status and Self-Perception in Adolescents Exposed to a High Level of Fluoride in Water. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pini NI, Sundfeld-Neto D, Aguiar FH, Sundfeld RH, Martins LR, Lovadino JR, Lima DA. Enamel microabrasion: An overview of clinical and scientific considerations. World J Clin Cases. 2015;3:34-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | McCloskey RJ. A technique for removal of fluorosis stains. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109:63-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wong FS, Winter GB. Effectiveness of microabrasion technique for improvement of dental aesthetics. Br Dent J. 2002;193:155-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Loguercio AD, Correia LD, Zago C, Tagliari D, Neumann E, Gomes OM, Barbieri DB, Reis A. Clinical effectiveness of two microabrasion materials for the removal of enamel fluorosis stains. Oper Dent. 2007;32:531-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sinha S, Vorse KK, Noorani H, Kumaraswamy SP, Varma S, Surappaneni H. Microabrasion using 18% hydrochloric acid and 37% phosphoric acid in various degrees of fluorosis - an in vivo comparision. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2013;8:454-465. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Celik EU, Yildiz G, Yazkan B. clinical evaluation of enamel microabrasion for the aesthetic management of mild-to-severe dental fluorosis. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2013;25:422-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Price RB, Loney RW, Doyle MG, Moulding MB. An evaluation of a technique to remove stains from teeth using microabrasion. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1066-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Croll TP, Cavanaugh RR. Enamel color modification by controlled hydrochloric acid-pumice abrasion. II. Further examples. Quintessence Int. 1986;17:157-164. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Sundfeld RH, Franco LM, Gonçalves RS, de Alexandre RS, Machado LS, Neto DS. Accomplishing esthetics using enamel microabrasion and bleaching-a case report. Oper Dent. 2014;39:223-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Ardu S, Stavridakis M, Krejci I. A minimally invasive treatment of severe dental fluorosis. Quintessence Int. 2007;38:455-458. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Mondelli RF, Azevedo JF, Francisconi AC, Almeida CM, Ishikiriama SK. Comparative clinical study of the effectiveness of different dental bleaching methods - two years follow-up. J Appl Oral Sci. 2012;20:435-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Loyola-Rodriguez JP, Pozos-Guillen Ade J, Hernandez-Hernandez F, Berumen-Maldonado R, Patiño-Marin N. Effectiveness of treatment with carbamide peroxide and hydrogen peroxide in subjects affected by dental fluorosis: a clinical trial. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2003;28:63-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sundfeld RH, Croll TP, Briso AL, de Alexandre RS, Sundfeld Neto D. Considerations about enamel microabrasion after 18 years. Am J Dent. 2007;20:67-72. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Thylstrup A, Fejerskov O. Clinical appearance of dental fluorosis in permanent teeth in relation to histologic changes. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1978;6:315-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nevárez-Rascón M, Villegas-Ham J, Molina-Frechero N, Castañeda-Castaneira E, Bologna-Molina R, Nevárez-Rascón A. Tratamiento para manchas por fluorosis dental por medio de micro abrasión sin instrumentos rotatorios. CES Odontología. 2011;23:61-66. |

| 19. | Li Y. Safety controversies in tooth bleaching. Dent Clin North Am. 2011;55:255-263, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Goldberg M, Grootveld M, Lynch E. Undesirable and adverse effects of tooth-whitening products: a review. Clin Oral Investig. 2010;14:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lee SS, Zhang W, Lee DH, Li Y. Tooth whitening in children and adolescents: a literature review. Pediatr Dent. 2005;27:362-368. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Hanks CT, Fat JC, Wataha JC, Corcoran JF. Cytotoxicity and dentin permeability of carbamide peroxide and hydrogen peroxide vital bleaching materials, in vitro. J Dent Res. 1993;72:931-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Costa CA, Riehl H, Kina JF, Sacono NT, Hebling J. Human pulp responses to in-office tooth bleaching. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:e59-e64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Benetti AR, Valera MC, Mancini MN, Miranda CB, Balducci I. In vitro penetration of bleaching agents into the pulp chamber. Int Endod J. 2004;37:120-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Camargo SE, Valera MC, Camargo CH, Gasparoto Mancini MN, Menezes MM. Penetration of 38% hydrogen peroxide into the pulp chamber in bovine and human teeth submitted to office bleach technique. J Endod. 2007;33:1074-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gökay O, Yilmaz F, Akin S, Tunçbìlek M, Ertan R. Penetration of the pulp chamber by bleaching agents in teeth restored with various restorative materials. J Endod. 2000;26:92-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Choukroune C. Tooth eruption disorders associated with systemic and genetic diseases: clinical guide. Journal of Dentofacial Anomalies and Orthodontics. 2017;20:402. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Balan B, Madanda Uthaiah C, Narayanan S, Mookalamada Monnappa P. Microabrasion: an effective method for improvement of esthetics in dentistry. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:951589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Train TE, McWhorter AG, Seale NS, Wilson CF, Guo IY. Examination of esthetic improvement and surface alteration following microabrasion in fluorotic human incisors in vivo. Pediatr Dent. 1996;18:353-362. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Dalzell DP, Howes RI, Hubler PM. Microabrasion: effect of time, number of applications, and pressure on enamel loss. Pediatr Dent. 1995;17:207-211. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Waggoner WF, Johnston WM, Schumann S, Schikowski E. Microabrasion of human enamel in vitro using hydrochloric acid and pumice. Pediatr Dent. 1989;11:319-323. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Tong LS, Pang MK, Mok NY, King NM, Wei SH. The effects of etching, micro-abrasion, and bleaching on surface enamel. J Dent Res. 1993;72:67-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Dahl JE, Pallesen U. Tooth bleaching--a critical review of the biological aspects. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:292-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Schillingburg HAT, Grace C. Thickness of enamel and dentin. J South Calif State Dent Assoc. 1973;41:33-36. |

| 35. | Griffin RG, Grower MF, Ayer WA. Effects of solutions used to treat dental fluorosis on permeability of teeth. J Endod. 1977;3:139-143. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zuanon AC, Santos-Pinto L, Azevedo ER, Lima LM. Primary tooth enamel loss after manual and mechanical microabrasion. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30:420-423. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Ramalho KM, Aranha ACC, de Paula Eduardo C, Rocha RG, Bello-Silva MS, Lampert F, Esteves-Oliveira M. Quantitative analysis of dental enamel removal during a microabrasion technique. Clinical and Laboratorial Research in Dentistry. 2014;20:181-189. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Pini NIP, Lima DANL, Sundfeld RH, Ambrosano GMB, Aguiar FHB, Lovadino JR. In Situ assessment of the saliva effect on enamel morphology after microabrasion technique. Braz J Oral Sci. 2014;13:187-192. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 39. | Scribante A, Contreras-Bulnes R, Montasser MA, Vallittu PK. Orthodontics: Bracket Materials, Adhesives Systems, and Their Bond Strength. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1329814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Franco LM, Machado LS, Salomão FM, Dos Santos PH, Briso AL, Sundfeld RH. Surface effects after a combination of dental bleaching and enamel microabrasion: An in vitro and in situ study. Dent Mater J. 2016;35:13-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Lins R, Duarte RM, Meireles SS. Influence of three treatment protocols for dental fluorosis in the enamel surface: An in vitro study. Revista Científica do CRO-RJ (Rio de Janeiro Dental Journal). 2019;4:79-86. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 42. | Doneria D, Keshav K, Chauhan SPS. A combination technique of microabrasion and remineralizing agent for treatment of dental fluorosis stains. SRM Journal of Research in Dental Sciences. 2018;9:145. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Seong J, Virani A, Parkinson C, Claydon N, Hellin N, Newcombe RG, West N. Clinical enamel surface changes following an intra-oral acidic challenge. J Dent. 2015;43:1013-1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Poggio C, Dagna A, Chiesa M, Colombo M, Scribante A. Surface roughness of flowable resin composites eroded by acidic and alcoholic drinks. J Conserv Dent. 2012;15:137-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Sundfeld D, Pavani CC, Pavesi Pini NI, Machado LS, Schott TC, Bertoz APM, Sundfeld RH. Esthetic recovery of teeth presenting fluorotic enamel stains using enamel microabrasion and home-monitored dental bleaching. J Conserv Dent. 2019;22:401-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |