Published online Feb 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i3.606

Peer-review started: December 7, 2019

First decision: December 23, 2019

Revised: December 27, 2019

Accepted: January 8, 2020

Article in press: January 8, 2020

Published online: February 6, 2020

Processing time: 60 Days and 17.3 Hours

Prostatic stromal sarcoma presenting with rhabdoid features is extremely rare, and only four cases have been reported in the English-language literature to date. Accordingly, there is no absolute definition of this group of tumors as yet, and our overall understanding of its morphological features, therapeutic regimen and prognosis is limited.

A 34-year-old male patient was referred to our hospital to address a 2-mo history of hematuria and progressive dysuria. Pelvic computed tomography scan revealed a 6.0 cm × 5.2 cm × 7.2 cm mass in the prostate, with bladder invasion. The patient underwent transurethral prostatectomy as upfront therapy. He refused further treatment and died of uncontrollable tumor growth 3 mo after surgery. Pathology analysis revealed the stroma to be pleomorphic, with a huge number of atypical spindle cells. Rhabdomyoblastic cells, with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, were detected. The spindle cells were positive for vimentin, INI1 and β-catenin, and the rhabdomyoblastic cells were positive for MyoD1, myogenin and INI1. The spindle cells and epithelial cells were sporadically positive for P53.

The prostatic stromal sarcoma tumor was immunoreactive for β-catenin, suggesting a role for the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in this tumor type.

Core tip: An extremely rare case of prostatic stromal sarcoma is presented. The rhabdoid component represented only a minor part of the tumor, as revealed by pathology study. Detailed diagnostic information on this rare tumor type has been reported in the literature, although the molecular pathogenesis remains largely unknown. The β-catenin immunoreactivity of the tumor in our case suggests that the tumorigenesis process may involve the Wnt pathway.

- Citation: Li RG, Huang J. Clinicopathologic characteristics of prostatic stromal sarcoma with rhabdoid features: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(3): 606-613

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i3/606.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i3.606

Prostatic stromal sarcoma (PSS), which accounts for less than 1% of all prostate neoplasms, is a rare type of prostate malignancy, and cases with rhabdoid features are especially rare. To date, only four cases of PSSs with rhabdoid differentiation have been reported in the English-language literature[1-4]. For general PSS, the tumors occur in adult patients of all ages, who usually present with severe urinary obstruction, hematuria, and dysuria. The tumor can develop in the absence of elevated prostate-specific antigen (PSA), making it difficult to detect its progression. Prognosis is poor, with a median survival time of less than 15 mo and only 10% of patients survive for more than 3 years.

No absolute definition of PSS has been published and its morphological features, therapeutic regimen and prognosis profile have yet to be fully elucidated, especially PSS with rhabdoid features. We recently experienced a case of PSS with rhabdoid differentiation, which prompted us to study the literature to examine the clinicopathologic features, clinical outcome, and prognosis of the tumor of this exceedingly rare type of tumor.

A 34-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with complaints of hematuria and progressive dysuria that had lasted for 2 mo.

The patient had undergone transurethral cystoscopy at a local primary hospital, 2 wk prior to his presentation at our clinic. The postoperative pathology analysis had revealed malignant changes in the prostate (details unknown). The patient also had a history of schizophrenia and was being treated with chlorpromazine (50 mg bid).

The patient was an only child, and his parents had no similar clinical manifestations, including hematuria and dysuria.

On physical examination, the patient demonstrated obvious anemic appearance. Digital rectal examination showed the texture of the prostate to be generally hard, with palpable nodules.

Blood examinations showed extremely low levels of hemoglobin (54 g/L; normal: ≥ 130 g/L). The serum total PSA was 0.816 ng/mL (normal range: 0.1-4 ng/mL). Urinalysis revealed elevated erythrocytes and leukocytes. The results of blood biochemistry tests, coagulation function test, and stool analysis were normal.

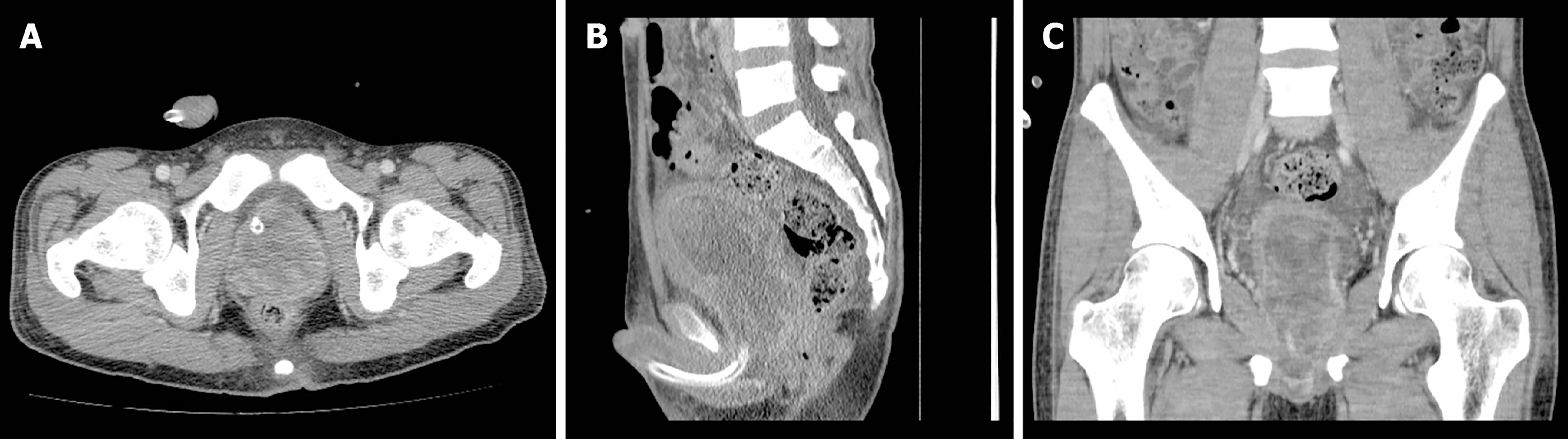

The preoperative chest X-ray and electrocardiograph were normal. Pelvic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a 6.0 cm × 5.2 cm × 7.2 cm prostatic mass, with indication of invasion into the posterior wall of the bladder (Figure 1). The patient and his family refused additional examinations by positron emission tomography-CT and magnetic resonance imaging scan, due to personal economic conditions.

PSS with rhabdoid features.

Bladder clot evacuation and prostatic tissue biopsy were immediately carried out by transurethral prostatectomy. The patient then received blood transfusion and cefoxitin sodium (4 g IVD bid).

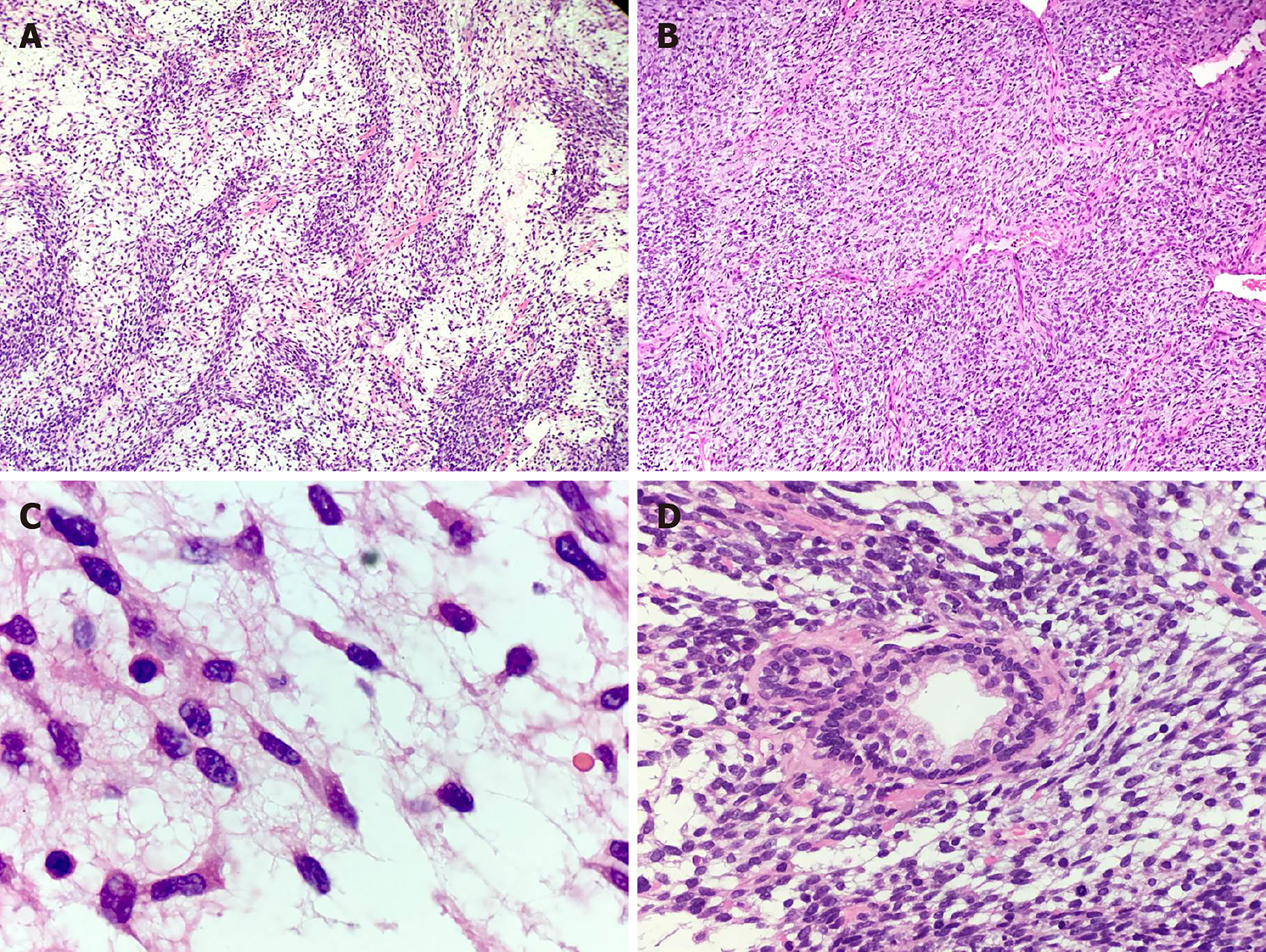

Gross examination of the prostate specimens showed that they were gray-red in color, soft in texture, and fish meat-like in appearance. For microscopic analysis (Figure 2), formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The spindle cells were found to be arranged densely and loosely at intervals, with a widespread myxoid background. At high magnification, the spindle tumor cells showed fascicular, whorled and storiform arrangements. There were areas of poor differentiation of embryonoid rhabdomyoblasts with eccentric nuclei and unremarkable cross-striations, which showed abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor cells were characterized by nuclear division, with up to 20 mitoses per 10 high power field. A scattered distribution of prostatic glandular tissue could be seen, but there were no malignant glandular epithelial cells. Angiomatoid type cells were observed in certain areas.

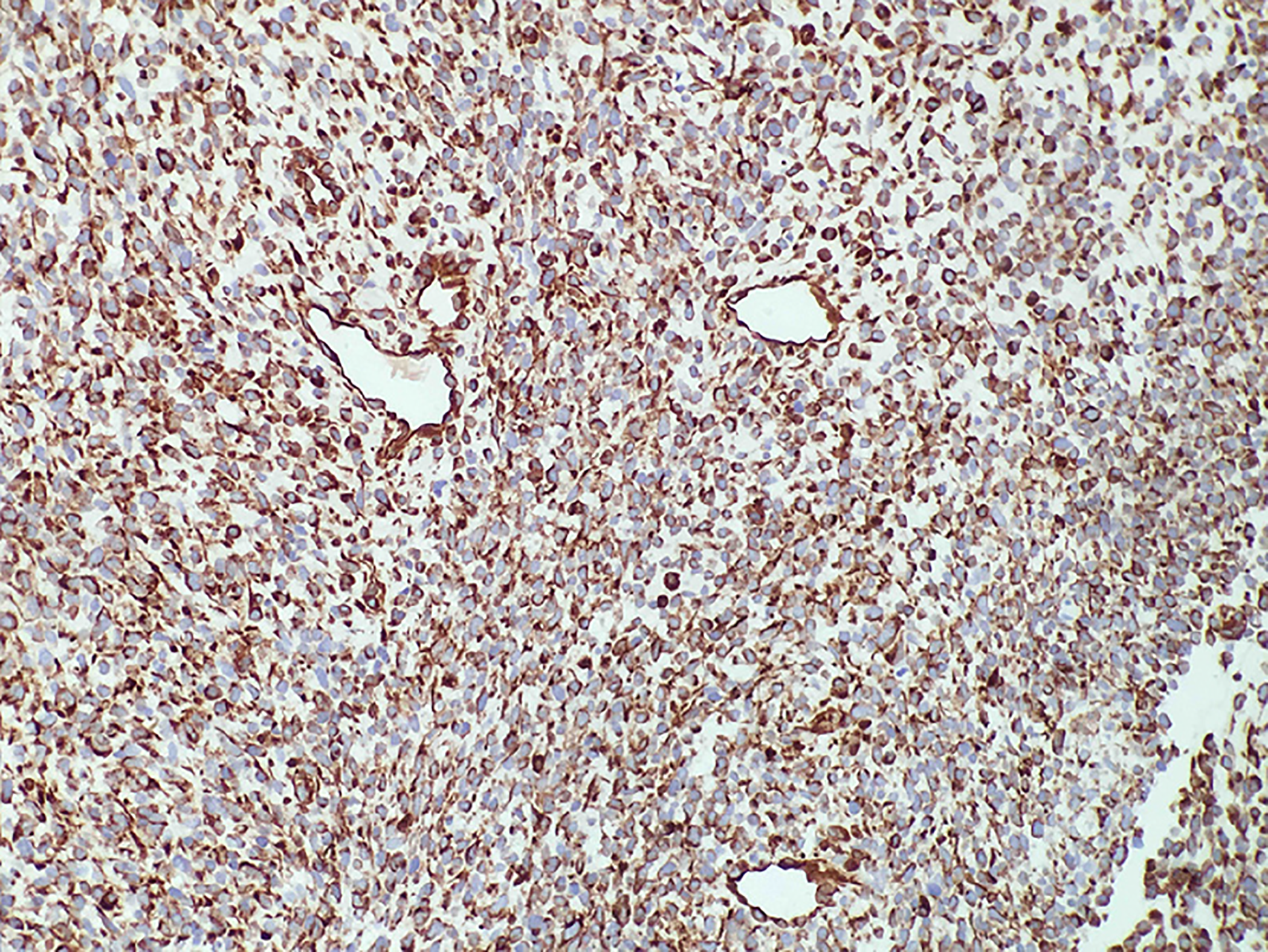

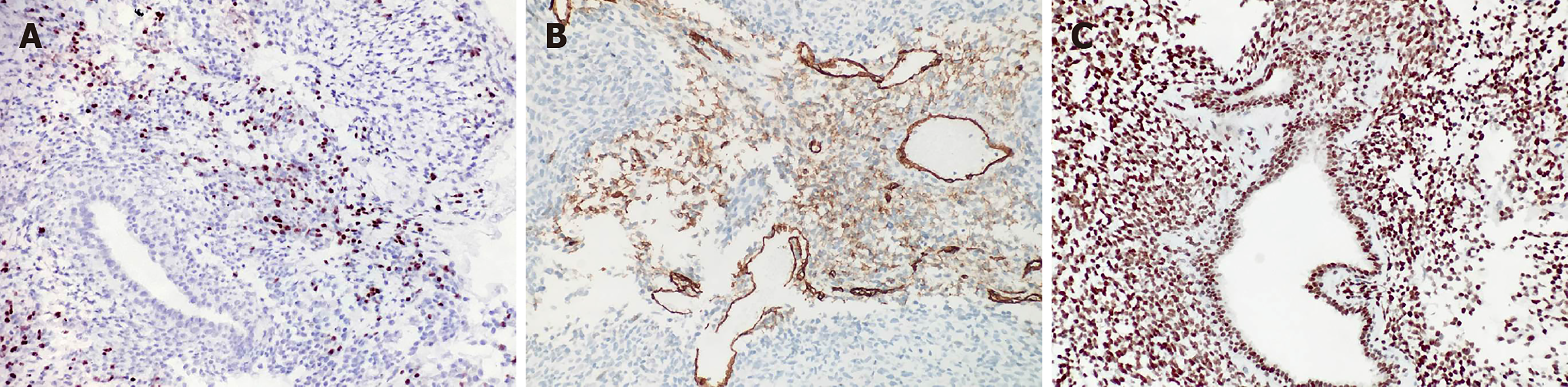

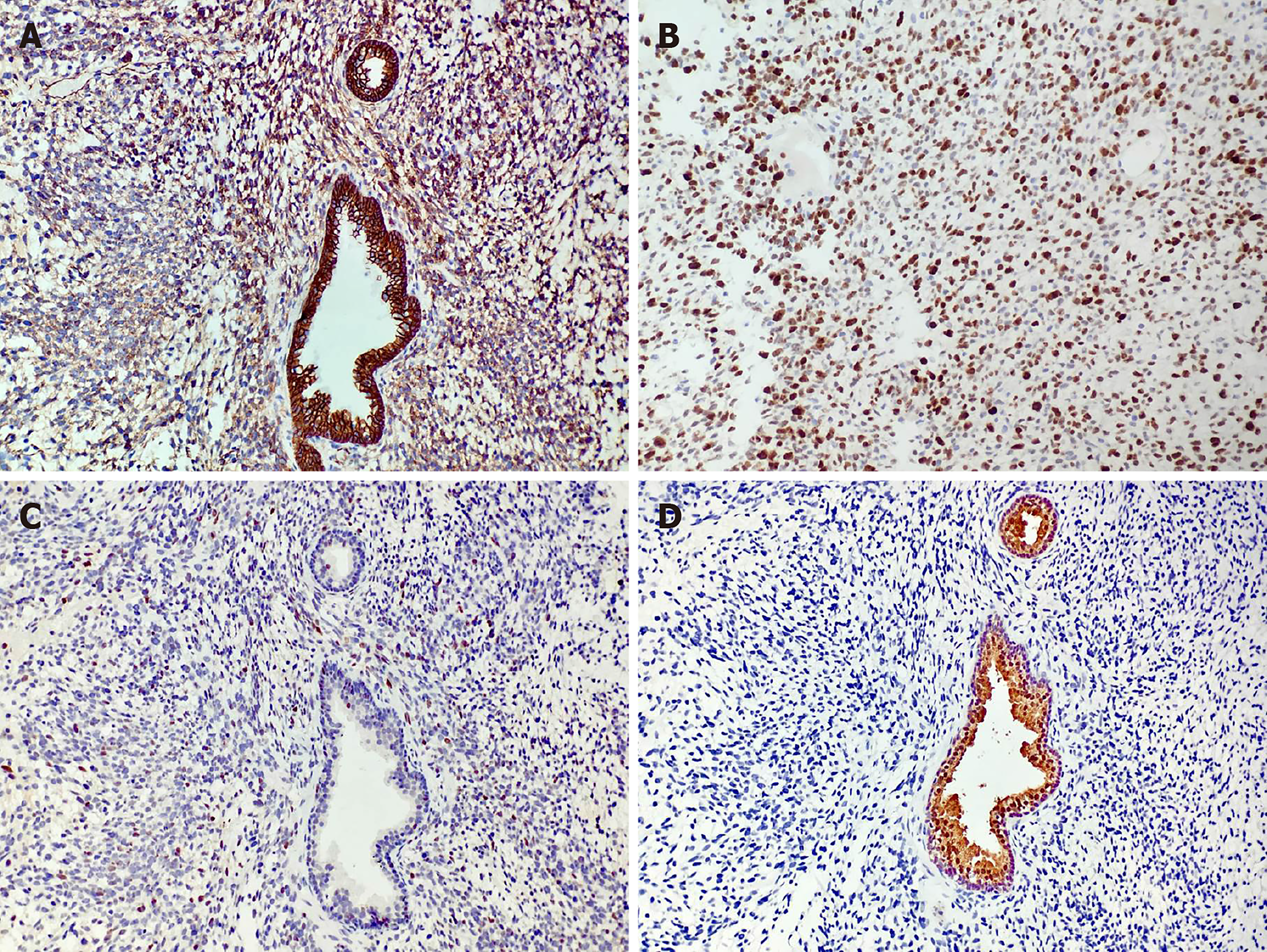

Immunohistochemical experiments were performed automatically using a Roche BenchMark XT automatic immunohistochemical instrument. All antibodies were ready-to-use purchased from Beijing Zhongshan Biotechnology (Beijing, China). Immunostaining for vimentin was diffuse and strong (Figure 3). The rhabdomyoblasts stained positive for MyoD1 and myogenin (Figure 4); staining for CD34, progesterone receptors, actin, CD117, DOG-1, S-100, Syn, and NSE was negative. The spindle cells and rhabdomyoblasts stained positive for INI1 (Figure 4). The cytoplasm and cellular membrane of the spindle cells were immunoreactive for β-catenin, whereas the nuclei were not. The Ki-67 labeling index was 75%. P53 staining was sporadically positive in both the spindle cells and glandular epithelial cells. The glandular epithelial cells were focally positive for PSA immunostaining (Figure 5).

Although the patient was advised to undergo further examination and radical cystoprostatectomy, he denied any intervention and died of uncontrollable tumor and severe bleeding 3 mo after the initial surgery.

PSS is a rare type of prostatic cancer, accounting for 0.1% of all prostatic malignancies in adults[5]. PSS with rhabdoid or rhabdomyoblastic features is exceptionally rare, with only four cases reported in the English-language literature. Given this small number of cases of PSS with rhabdoid features, a more detailed analysis of its clinicopathology and survival has not been performed until now.

The diagnosis of PSS is very difficult but can be supported by careful evaluation of clinical and pathology data. On magnetic resonance examination, most PSSs appear as homogeneous, low-signal masses on T1-weighted images and heterogeneously massed with areas of intermediate and high T2 signals. In the imaging differential diagnosis, one should consider prostatic adenocarcinoma, which infiltrates the gland without significantly enlarging the prostate in the early stage of the disease.

PSS is characterized by the growth pattern of phyllodes tumors with malignant pleomorphic stroma or those that exhibit a fascicular growth pattern similar to that of leiomyosarcoma. Stromal overgrowth with cellular atypia, a high mitotic rate, and necrosis are the most important features that have prognostic value. Several studies have demonstrated the stromal-epithelial interaction nature of these lesions. The true pathomechanism of PSS is unknown, due to the limited number of reported cases, and there is no agreement on the naming of these tumors. However, variable features have been used to qualify tumor grade; these include stromal cellularity, cytologic atypia, stromal-to-epithelial ratio, necrosis, and mitotic activity[6]. Tumor grade might be related to the sarcomatoid component, local invasion, distant metastasis, and the treatment response.

All four previous cases and our case were of a high-grade sarcoma with focal rhabdoid differentiation (Table 1). All five cases were characterized by increased stromal cellularity, high mitotic rate, and areas of necrosis. The stromal cells were spindle-shaped and organized in fascicular, whorled, or storiform formations. The embryonoid rhabdomyoblasts showed poor differentiation. Special staining with, toluidine blue, and periodic acid-Schiff was performed to identify the rhabdomyoblasts in the first case (reported by Yokota et al[4]) but without immunohistochemical examination.

| Ref. | Age in yr | Clinical presentation | Pattern of H and E | Pattern of IH | Treatment | Outcome |

| Yokota et al[4] | 45 | Hematuria, dysuria, episodes of intermittent fever | Striking proliferation of undifferentiated cells of mesenchymal type with round and spindle-shaped nuclei were shown in the stroma; PAS stain was positive | PSA (+) | Colostomy | Recurrence with death 4 mo after surgery |

| De Raeve et al[1] | 36 | Recurrent urinary obstruction | Phyllodes, cystically dilated ducts; Spindle-shaped tumor cells; Fascicularis, mitotic figures (more than 38/10 HPF); Well-differentiated rhabdomyoblasts | Rhabdomyoblastic cells: muscle specific actin (+), desmin (+), myoD1 (+); Stromal tumor cells: Ki-67 (+), CD34 (-), α-SMA (-), desmin (-), actin (-) | Prostatectomy followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy | Recurrence after prostatectomy 4 mo later |

| Herawi et al[3] | N/A | N/A | Focal rhabdomyosarcomatous differentiation | Rhabdomyoblastic cells: desmin (+), myogenin (+) | N/A | N/A |

| Kim et al[2] | 31 | Voiding difficulty and anal pain | Biphasic growth pattern with spindle and epithelioid cells, highly cellular spindle tumor cells with focal nuclear pleomorphism; Focal cells with rhabdoid features | Spindle cells and epithelioid tumor cells: vimentin (+), CD34 (+), progesterone receptors (+), INI1 (+); Rhabdoid cells: INI1 (+) | Radical prostatectomy followed by cystectomy | Recurrence, with death 3 mo after cystectomy |

| Current case | 34 | Hematuria and progressive dysuria | Huge number of atypia spindle cells; Poor differentiation of embryonoid rhabdomyoblasts with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm | Spindle cells: vimentin (+), β-catenin (+); Rhabdomyoblastic cells: MyoD1 (+), myogenin (+) INI1 (+); Epithelioid cells: PSA (+) | Transurethral prostatectomy | Died of uncontrollable tumor and severe bleeding 3 mo after surgery |

PSSs are characterized as spindle-cell lesions that originated from special prostatic stromal tissue. Our case and another case[7] showed β-catenin immunoreactivity in the cytoplasm and cellular membrane, which suggested that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway may play an important role in the development and progression of PSS. Previous experiments demonstrated that cytosolic β-catenin is translocated to the nucleus, where it binds to transcription factor-4 and regulates the transcription of genes involved in proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis when the Wnt pathway is activated[8,9]. Active Wnt signaling can prevent GSK-3β-induced degradation of Snail, and thereby promote epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition[10]. Bouron-Dal et al[11] observed using immunohistochemistry, a cytoplasmic location of β-catenin with a membrane reinforcement in 12 cases of rhabdomyosarcoma, without any nuclear accumulation of β-catenin; this finding is consistent with ours.

Most PSS cases show positive immunoreactivity for vimentin but are negative for CD117[3]. Prior studies showed positive CD34 and progesterone receptors in a fraction of the cases, but these findings were not specific[2,12]. Moreover, some cases, including the present case, showed negativity for CD34 and progesterone receptors[1]; of note, the progesterone receptor can also be expressed in smooth muscle tumors. Usually, the Ki-67 cellular content is markedly increased in the high-grade tumor cells of PSS, and the expression of Ki-67 might be an adjuvant diagnostic index for judging the tumor prognosis. PSS tumors also positively react with special biomarkers when they are associated with other differentiations. Despite these reported findings, the detailed immunohistochemical characteristics of these tumor cells are largely unknown.

In the differential diagnosis of PSS, one should consider prostate adenocarcinoma, metastatic tumors, and sarcomas arising from the bladder and seminal vesicle. There are other PSSs, such as rhabdomyosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma and extragastrointestinal stromal tumors (EGISTs), which need to be clinically distinguished from PSS. Prostatic rhabdomyosarcoma occurs predominantly in male infants and children who have aggressive clinical manifestations. Histologically, rhabdomyosarcoma is composed of primitive undifferentiated, round- to spindle-shaped cells, without discernible differentiation or with only focal rhabdomyoblastic differentiation. The tumor cells are typically positive for MyoD1 and myogenin.

Deletions and mutations of the INI1 gene (22q11.2) have been detected in most malignant rhabdoid tumors. In contrast to malignant rhabdoid tumors, which typically have deletion of 22q11.2, the composite extrarenal rhabdoid tumors do not evolve by way of genetic alteration[13]. In the current case, the rhabdoid tumor cells represented only a minor part of the tumor with immunoreactivity to INI1, which helped to exclude the diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma. EGISTs are relatively rare, soft tissue neoplasms arising from the extragastrointestinal tract, with mutations in the c-kit (CD117) exons 9, 11, 13 and 17 and in the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha exons 12, 14 and 18[14]. In contrast to the overexpression of c-kit in EGISTs, all PSSs (including the present case) showed no detectable c-kit expression. There was no malignant epithelial component or immunohistochemical evidence of epithelial differentiation that distinguished itself from sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate.

The optimal treatment for PSS with rhabdoid features is still unknown. Radical excision (prostatectomy or cystoprostatectomy) appears to be the preferred treatment among the reported management strategies, as it is most likely to result in long-term survival[15,16]. However, the PSS with rhabdoid features recurred in each patient with high-grade tumors and metastases (Table 1). The effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy have not been fully investigated; although, Reese et al[17] had previously reported a case of PSS showing a complete pathologic response in the primary lesion following neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation. Further study on the biological characteristics and long-term follow-up is needed, particularly due to the propensity of these neoplasms to recur over time.

There are a lot of gaps that remain in our knowledge of the pathogenesis of PSS with rhabdoid features, due to the limited number of cases. We found through our case and review of the literature that β-catenin immunoreactivity is detected in the tumor, suggesting that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway may play an important role in the pathogenesis of PSS.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Andrejic-Visnjic B S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Webster JR E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | De Raeve H, Jeuris W, Wyndaele JJ, Van Marck E. Cystosarcoma phyllodes of the prostate with rhabdomyoblastic differentiation. Pathol Res Pract. 2001;197:657-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim JY, Cho YM, Ro JY. Prostatic stromal sarcoma with rhabdoid features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2010;14:453-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Herawi M, Epstein JI. Specialized stromal tumors of the prostate: a clinicopathologic study of 50 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:694-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yokota T, Yamashita Y, Okuzono Y, Takahashi M, Fujihara S, Akizuki S, Ishihara T, Uchino F, Iwata T. Malignant cystosarcoma phyllodes of prostate. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1984;34:663-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lobe TE, Wiener E, Andrassy RJ, Bagwell CE, Hays D, Crist WM, Webber B, Breneman JC, Reed MM, Tefft MC, Heyn R. The argument for conservative, delayed surgery in the management of prostatic rhabdomyosarcoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1084-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bannowsky A, Probst A, Dunker H, Loch T. Rare and challenging tumor entity: phyllodes tumor of the prostate. J Oncol. 2009;2009:241270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kuhnen C, Herter P, Müller O, Muehlberger T, Krause L, Homann H, Steinau HU, Müller KM. Beta-catenin in soft tissue sarcomas: expression is related to proliferative activity in high-grade sarcomas. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:1005-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4088] [Cited by in RCA: 4448] [Article Influence: 234.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gregorieff A, Pinto D, Begthel H, Destrée O, Kielman M, Clevers H. Expression pattern of Wnt signaling components in the adult intestine. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:626-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yook JI, Li XY, Ota I, Fearon ER, Weiss SJ. Wnt-dependent regulation of the E-cadherin repressor snail. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11740-11748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bouron-Dal Soglio D, Rougemont AL, Absi R, Giroux LM, Sanchez R, Barrette S, Fournet JC. Beta-catenin mutation does not seem to have an effect on the tumorigenesis of pediatric rhabdomyosarcomas. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2009;12:371-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gaudin PB, Rosai J, Epstein JI. Sarcomas and related proliferative lesions of specialized prostatic stroma: a clinicopathologic study of 22 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:148-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fuller CE, Pfeifer J, Humphrey P, Bruch LA, Dehner LP, Perry A. Chromosome 22q dosage in composite extrarenal rhabdoid tumors: clonal evolution or a phenotypic mimic? Hum Pathol. 2001;32:1102-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liu S, Yu Q, Han W, Qi L, Zu X, Zeng F, Xie Y, Liu J. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the prostate: A case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1925-1929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mao QQ, Wang S, Wang P, Qin J, Xia D, Xie LP. Treatment of prostatic stromal sarcoma with robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy in a young adult: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:2542-2544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Osaki M, Osaki M, Takahashi C, Miyagawa T, Adachi H, Ito H. Prostatic stromal sarcoma: case report and review of the literature. Pathol Int. 2003;53:407-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Reese AC, Ball MW, Efron JE, Chang A, Meyer C, Bivalacqua TJ. Favorable response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation in a patient with prostatic stromal sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:e353-e355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |