Published online Feb 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i3.568

Peer-review started: November 12, 2019

First decision: December 12, 2019

Revised: December 31, 2019

Accepted: January 8, 2020

Article in press: January 8, 2020

Published online: February 6, 2020

Processing time: 85 Days and 16.9 Hours

Loss of graft function after liver transplantation (LT) inevitably requires liver retransplant. Retransplantation of the liver (ReLT) remains controversial because of inferior outcomes compared with the primary orthotopic LT (OLT). Meanwhile, if accompanied by vascular complications such as arterial and portal vein (PV) stenosis or thrombosis, it will increase difficulties of surgery. We hereby introduce our center's experience in ReLT through a complicated case of ReLT.

We report a patient who suffered from hepatitis B-associated cirrhosis and underwent LT in December 2012. Early postoperative recovery was uneventful. Four months after LT, the patient’s bilirubin increased significantly and he was diagnosed with an ischemic-type biliary lesion caused by hepatic artery occlusion. The patient underwent percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage and repeatedly replaced intrahepatic biliary drainage tube regularly for 5 years. The patient developed progressive deterioration of liver function and underwent liver re-transplant in January 2019. The operation was performed in a classic OLT manner without venous bypass. Both the hepatic artery and PV were occluded and could not be used for anastomosis. The donor PV was anastomosed with the recipient’s left renal vein. The donor hepatic artery was connected to the recipient’s abdominal aorta. The bile duct reconstruction was performed in an end-to-end manner. The postoperative process was very uneventful and the patient was discharged 1 mo after retransplantation.

With the development of surgical techniques, portal thrombosis and arterial occlusion are no longer contraindications for ReLT.

Core tip: We report the case of a patient who underwent retransplantation for graft liver failure due to a biliary complication after liver transplantation. The portal vein (PV) thrombosis and hepatic artery occlusion posed great challenges for surgery. The operation was performed in a classic orthotopic liver transplantation manner without venous bypass. Because the blood flow of the PV was not ideal after removing the thrombosis, the graft PV was anastomosed with the recipient’s left renal vein. The hepatic artery was anastomosed with the abdominal aorta. Biliary anastomosis was performed in an end-to-end manner. The patient was discharged from hospital with normal liver and kidney function.

- Citation: Li J, Guo QJ, Jiang WT, Zheng H, Shen ZY. Complex liver retransplantation to treat graft loss due to long-term biliary tract complication after liver transplantation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(3): 568-576

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i3/568.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i3.568

Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is currently the life-saving therapeutic modality for patients with end-stage liver failure, with 5- and 10-year survival rates of over 70% and 65%, respectively[1]. However, a significant proportion of patients (10.0%-19.4%) suffer graft loss following primary LT[1-3]. Retransplantation of the liver (ReLT) is the only viable treatment option for patients with irreversible graft failure. The incidence of ReLT varies between 5% and 22% worldwide[4-6]. ReLT presents a clinical dilemma because it is associated not only with ethical and economic issues, but also with a significantly poorer outcome compared with that following primary transplantation[7]. Meanwhile, the operation and clinical treatment of ReLT are complex and technically challenging. Here, we introduce our experience with a complex ReLT in our center, and discuss the surgical indications, prognostic factors, and operative technical difficulties of ReLT.

Progressive jaundice of the skin and eyes with intermittent black stools and confusion for 1 year.

A 38-year-old yellow man underwent LT on December 26, 2012 for the first time due to decompensation of hepatitis B cirrhosis accompanied by hepatic encephalopathy and gastrointestinal bleeding. The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged from the hospital with normal liver function 1 mo after the operation.

Four months after surgery, ischemic-type bile duct injury occurred and percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage was performed. The intrahepatic biliary drainage tube was indwelling for a long time and replaced regularly. The total bilirubin level of the patient fluctuated between 60-100 µmol/L. From the 5th year after the operation, the bilirubin level of the patient has been progressively increased accompanied by intermittent black stools and blurred consciousness, and he was put on the transplant list again.

The patient underwent LT in 2012. The donor was a 42-year-old yellow man after brain death due to trauma. Graft liver had neither micro- nor macro-steatosis. Classical OLT was performed without using bypass. Intraoperative basiliximab induction plus triple immunosuppressive regimen including tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and methylprednisolone was given.

The patient suffered from hepatitis B from birth without regular antiviral treatment.

Physical examination on admission revealed marked jaundice of the skin and eyes.

At the time of last admission, the laboratory parameters were as follows: AST 53 U/L, ALT 38 U/L, total bilirubin 325 µmol/L, direct bilirubin 219 µmol/L, alkaline phosphatase 153 U/L, serum albumin 27.0 g/L, serum urea nitrogen 7.37 mmol/L, serum creatinine 54 µmol/L, hemoglobin 10.3 g/dL, prothrombin time 32 s, and prothrombin activity 29%. Serum virology tests including hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus (HCV), and cytomegalovirus were negative. Serum autoimmunity antibodies were negative.

From the 4th mo after primary LT, abdominal ultrasound suggested diffuse liver damage and absence of blood flow in the main hepatic artery. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography examination showed multiple stenosis of the intrahepatic biliary tract and formation of abscess in the hilum.

From the 5th year after primary LT, abdominal enhanced computed tomography showed portal vein (PV) thrombosis with cavernous degeneration of the PV (Figure 1A) and occlusion of the hepatic artery (Figure 1B). Meanwhile, a significant splenorenal shunt could be seen (Figure 2).

Graft liver insufficiency, ischemic-type biliary lesion, hepatic encephalopathy, and portal hypertension.

Orthotopic liver re-transplantation was carried out on January 4, 2019. The wait time on the waiting list was 7 mo. The donor was a 45-year-old yellow man after brain death due to a cerebrovascular accident. The donor’s microbiological culture was negative. ReLT was performed in a classical OLT manner without bypass. The graft liver weighed 1400 g without micro- nor macro-steatosis. The warm ischemic time was 25 min, and the cold ischemic time was 10 h. After the recipient’s PV embolus was removed, the blood flow was not ideal. The PV of the recipient was ligated distally. After that, the PV of the graft liver was anastomosed end-to-end with the recipient's left renal vein through an interposition vein (iliac vein) (Figure 3A). After the blood flow opened, the graft liver was perfused very well (Figure 3D).

The process of arterial anastomosis was challenging, the recipient’s hepatic artery had been occluded, and the splenic artery was ligated during the first operation, neither of which was available. The external iliac artery from the same donor served as an interposition vessel for bridging the artery (Figure 3B). The celiac trunk artery of the graft liver was connected to the recipient’s abdominal aorta by the interposition vessel which was placed in the space through the mesentery and gastrohepatic ligament (Figure 3C). The bile duct reconstruction was performed in an end-to-end manner with a T-shaped drainage tube being placed inside (Figure 3D). The whole surgical procedure is illustrated in Figure 4. The ReLT took 1500 min. During the operation, 16 units of suspended red blood cells and 2000 mL of plasma were administered as needed. The patient’s vital signs were stable throughout the operation. Postoperative ICU stay was 5 d. The immunosuppressive regimen was exactly the same as that for the primary liver transplant. Low molecular weight heparin was administered in early 2 wk after surgery, followed by oral administration of warfarin to prevent thrombosis.

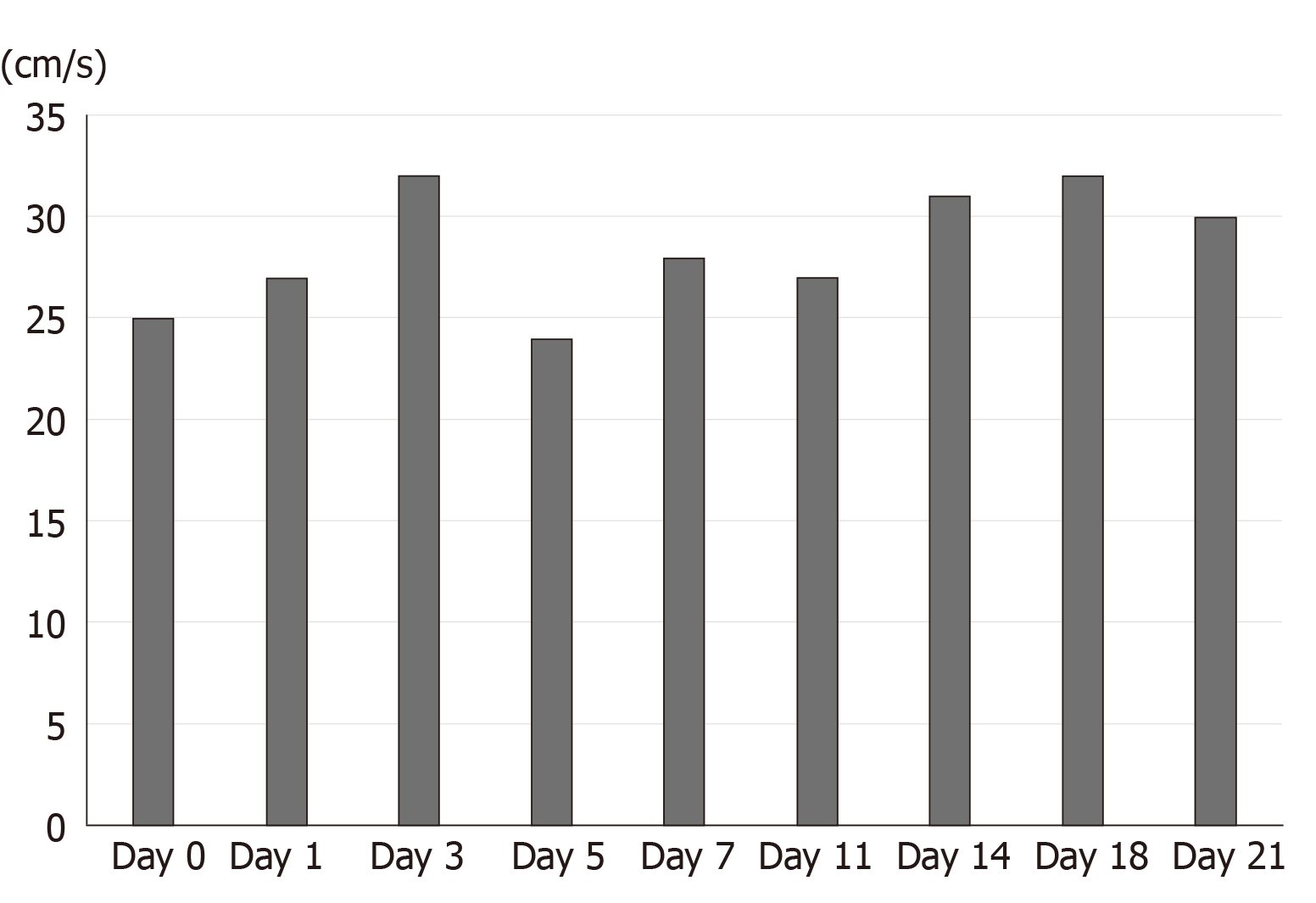

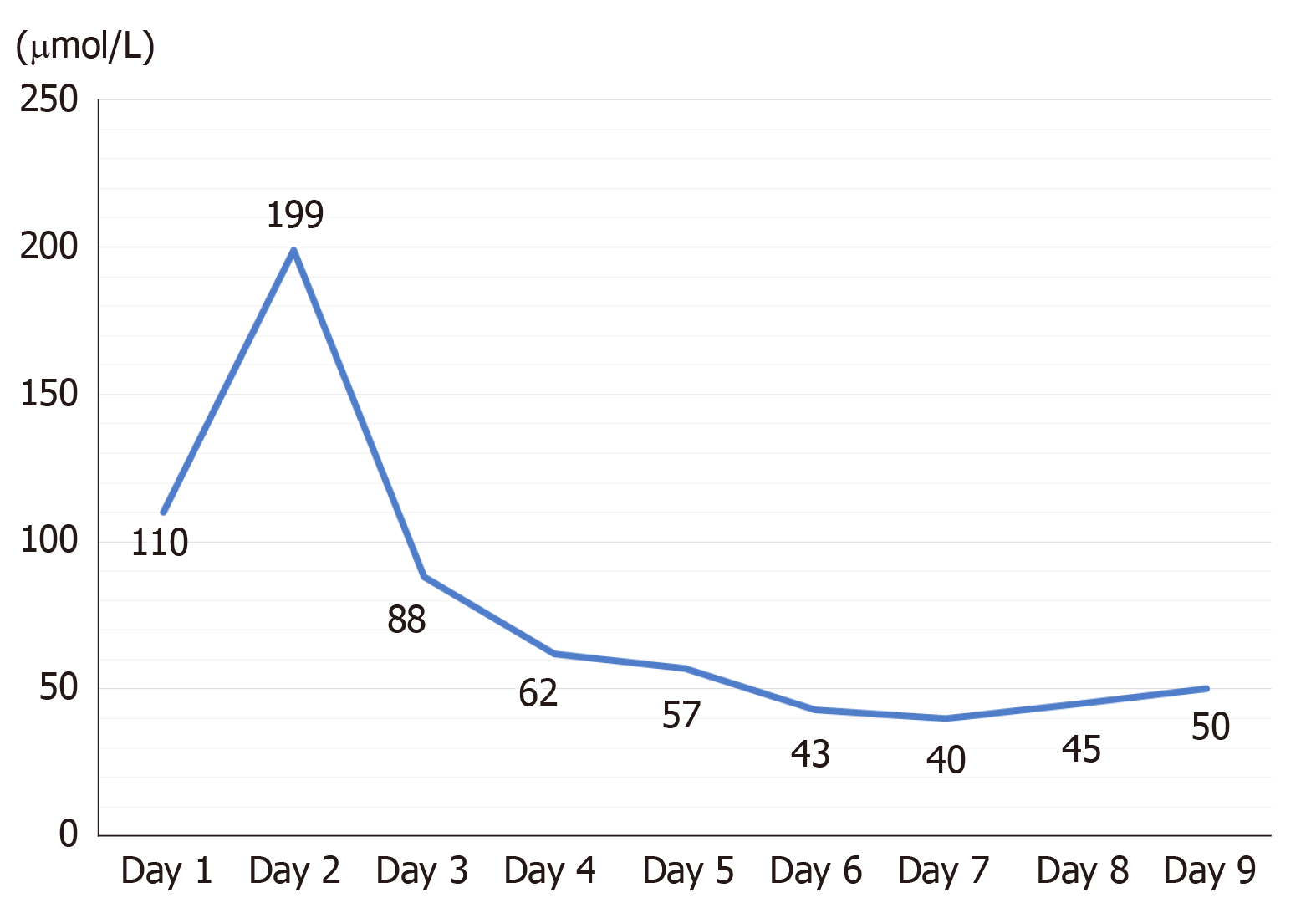

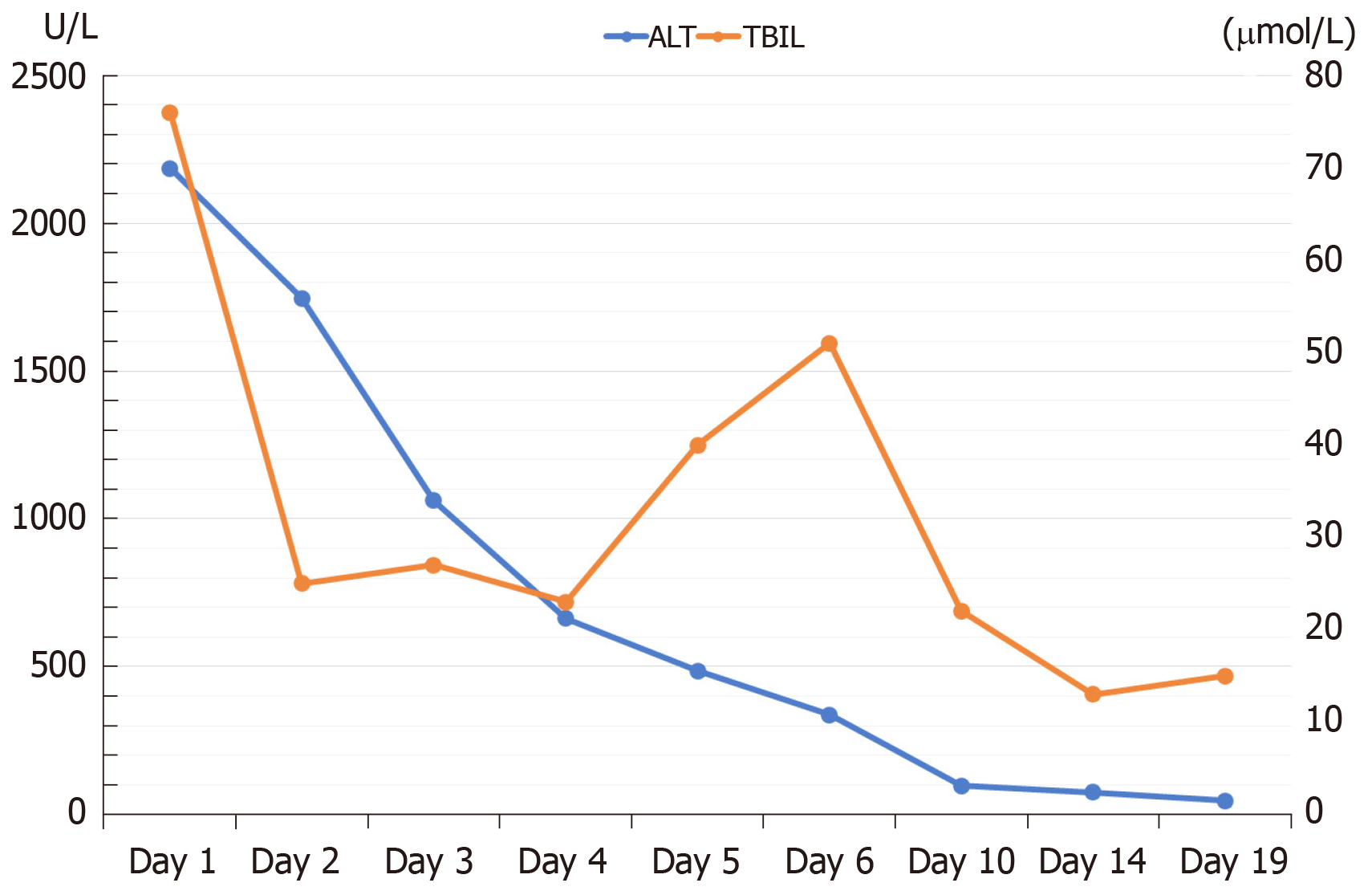

The intraoperative to 2-wk postoperative PV velocity fluctuated between 24-32 cm/s (Figure 5). The kidney function was not seriously affected. Serum creatinine increased significantly on the first day after surgery, peaked on the second day, and returned to the normal level on the fourth day after surgery (Figure 6). The patient’s liver function returned to the normal level about 2 wk after the operation (Figure 7). The patient was discharged in a good general state of health 30 d after ReLT. Ten months after re-transplantation, the patient was well and alive.

Liver retransplant is the only effective method to treat the irreversible graft liver failure. Since the early days of LT, retransplant has been recognized as a technical and surgical challenge[8,9]. Although advances in immunosuppressive agents have significantly prolonged graft and patient survival, patients who receive primary liver transplant are still at risk for graft failure and need liver retransplant. In European and American countries, liver retransplant accounts for 10%-20% of the total number of LT cases[6,10,11]. The operation and clinical treatment of liver retransplant are complex and technically difficult. Although trends over time have shown improved outcomes in graft and patient survival rates[6,12-14], retransplant results remain significantly worse than those for primary transplant[7].

Indications for retransplant are varied and have also changed with time[4]. According to the time interval between primary LT and retransplant, liver retransplant can be divided into early and late retransplant and the corresponding indications are significantly different. For early retransplant, graft liver dysfunction and vascular complications (hepatic artery thrombosis and PV thrombosis) are the main indications, which account for more than half of the total indications for retransplant[11,15,16]. About 70% of the graft losses within the first year seem to be early secondary to primary nonfunction and vascular thrombosis.

The indications for late retransplant mainly include chronic rejection, primary disease recurrence, and biliary complications. Other indications can be found in cytomegalovirus associated hepatitis, newly acquired autoimmune liver disease, and graft liver failure caused by newly acquired hepatitis B infection[6,17]. In China, the main cause of retransplant was biliary complications, which accounted for 50.0%-63.2% of the total number of the retransplant cases reported by different transplantation centers[18]. In Western countries, HCV is still one of the main indications for first and second LT but the emergence of safe and effective direct antiviral drugs had a great impact on the transplantation of HCV. The application of pre-transplant direct antiviral drugs resulted in clinical improvement in 1/3 of HCC-associated decompensated cirrhosis patients who were removed from the waiting list[19]. For this patient, the dysfunction of graft liver along with gastrointestinal bleeding and hepatic encephalopathy made him suitable for ReLT.

According to the time interval of ReLT, the difficulty of liver resection is obviously different. Early reoperation shows less tissue adhesion and a lower degree of portal hypertension than routine LT. However, there is usually severe abdominal adhesion for advanced ReLT recipients and the normal anatomical boundaries are not clear. Therefore, patients are faced with many problems, such as prolonged operation time, massive bleeding and blood transfusion during operation, and increased risk of damage to surrounding tissues, which require higher surgical techniques[20-22].

The key points of ReLT include the dissociation and resection of the diseased liver as well as vascular and biliary reconstruction. Tissue dissociation is carried out along the interstitial spaces around the liver in order to avoid damage to the surrounding organs. Recipient side blood vessels and bile ducts are retained as long as possible in order to perform anastomosis. If a serious adhesion is encountered during the operation, a sharp dissection with scissors and bipolar coagulation may prevent injury to adjacent hollow organs and massive bleeding according to the experience of our center.

Here, the patient had a PV thrombus (Grade III) according to Yerdel classification for PV thrombosis[23]. For grade III PV thrombus, Eversion thromboendovenectomy is usually conducted and the shunt vessel is ligated before removing the diseased liver according to our central experiences. If the portal flow is not ideal, different options are considered in order to establish an adequate portal flow (> 600 mL/min). Porto-systemic shunt collaterals are ligated and the left renal vein is divided[24]. Sometimes, a portal-reno anastomosis using a free iliac vein graft between the left renal vein and the PV can provide adequate portal inflow[25]. Additionally, PV can be anastomosed to recipient collaterals (coronary or choledochal veins). However, there were no appropriate collateral veins which can be used for anastomosis for this case. Finally, the graft PV was anastomosed to the recipient left renal vein using a free iliac vein graft in an end-to-end manner (Figure 4). The intraoperative and postoperative PV flow was ideal and had no significant effect on renal function. At the same time, this way of anastomosis could solve the problem of spleno-renal shunt very well.

For the reconstruction of the hepatic artery, the original anastomotic site should be resected in principle. If the recipient’s hepatic artery cannot be used, the graft hepatic artery usually needs to be anastomosed with the splenic artery or with the abdominal aorta via an interposition vessel. The latter is more commonly used in clinical practice, which allows for abundant arterial blood flow. However, there are also potential risks for abdominal aorta bridging such as blockage or partial blockage and rupture of the anastomosis due to pressure. Additionally, higher requirements for the surgical technology are needed and it will be unable to perform bridging if the recipient’s abdominal aortic has pathological changes such as atherosclerosis[26,27]. For this case, the patient’s hepatic artery had been occluded and the splenic artery was ligated during the primary LT, neither of which was available. The celiac trunk artery of the graft liver was connected to the recipient’s abdominal aorta by the external iliac artery which was placed in the space through the mesentery and gastrohepatic ligament (Figure 4).

The choice of biliary anastomosis mode mainly depends on the judgment of the recipient’s biliary tract. Roux-en-y anastomosis of the bile duct and jejunum should be performed when a definite preoperative biliary tract infection, poor biliary blood supply, and excessive biliary tract tension are present.

Although LT techniques continue to be improved, retransplant is often inevitable when the graft liver becomes dysfunctional or fails. How to improve the surgical effect of retransplant and timely and effectively allocate the liver source to the recipients who need urgent retransplant is always testing us. With the development of surgical techniques, portal thrombosis and arterial occlusion are no longer contraindications for ReLT.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Birk JW, Stankiewicz R, Memeo R S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Azoulay D, Linhares MM, Huguet E, Delvart V, Castaing D, Adam R, Ichai P, Saliba F, Lemoine A, Samuel D, Bismuth H. Decision for retransplantation of the liver: an experience- and cost-based analysis. Ann Surg. 2002;236:713-21; discussion 721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bramhall SR, Minford E, Gunson B, Buckels JA. Liver transplantation in the UK. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:602-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jiménez M, Turrión VS, Alvira LG, Lucena JL, Ardáiz J. Indications and results of retransplantation after a series of 406 consecutive liver transplantations. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:262-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kashyap R, Jain A, Reyes J, Demetris AJ, Elmagd KA, Dodson SF, Marsh W, Madariaga V, Mazariegos G, Geller D, Bonham CA, Cacciarelli T, Fontes P, Starzl TE, Fung JJ. Causes of retransplantation after primary liver transplantation in 4000 consecutive patients: 2 to 19 years follow-up. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:1486-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ma Y, Wang GD, He XS, Li JL. Liver retransplantation: a single-centre experience. Chin Med J (Engl). 2008;121:1987-1991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pfitzmann R, Benscheidt B, Langrehr JM, Schumacher G, Neuhaus R, Neuhaus P. Trends and experiences in liver retransplantation over 15 years. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:248-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Kitchens WH, Yeh H, Markmann JF. Hepatic retransplant: what have we learned? Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18:731-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Starzl TE, Iwatsuki S, Van Thiel DH, Gartner JC, Zitelli BJ, Malatack JJ, Schade RR, Shaw BW, Hakala TR, Rosenthal JT, Porter KA. Evolution of liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1982;2:614-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 560] [Cited by in RCA: 606] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shaw BW, Gordon RD, Iwatsuki S, Starzl TE. Hepatic Retransplantation. Transplant Proc. 1985;17:264-271. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Zarrinpar A, Hong JC. What is the prognosis after retransplantation of the liver? Adv Surg. 2012;46:87-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moon HH, Kim TS, Song S, Shin M, Chung YJ, Lee S, Choi GS, Kim JM, Kwon CHD, Lee SK, Joh J. Early Vs Late Liver Retransplantation: Different Characteristics and Prognostic Factors. Transplant Proc. 2018;50:2668-2674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Busuttil RW, Farmer DG, Yersiz H, Hiatt JR, McDiarmid SV, Goldstein LI, Saab S, Han S, Durazo F, Weaver M, Cao C, Chen T, Lipshutz GS, Holt C, Gordon S, Gornbein J, Amersi F, Ghobrial RM. Analysis of long-term outcomes of 3200 liver transplantations over two decades: a single-center experience. Ann Surg. 2005;241:905-16; discussion 916-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ghabril M, Dickson R, Wiesner R. Improving outcomes of liver retransplantation: an analysis of trends and the impact of Hepatitis C infection. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:404-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bellido CB, Martínez JM, Artacho GS, Gómez LM, Diez-Canedo JS, Pulido LB, Acevedo JM, Ruiz JP, Bravo MA. Have we changed the liver retransplantation survival? Transplant Proc. 2012;44:1526-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kamei H, Al-Basheer M, Shum J, Bloch M, Wall W, Quan D. Comparison of short- and long-term outcomes after early versus late liver retransplantation: a single-center experience. J Surg Res. 2013;185:877-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Masior Ł, Grąt M, Krasnodębski M, Patkowski W, Figiel W, Bik E, Krawczyk M. Prognostic Factors and Outcomes of Patients After Liver Retransplantation. Transplant Proc. 2016;48:1717-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yoo PS, Umman V, Rodriguez-Davalos MI, Emre SH. Retransplantation of the liver: review of current literature for decision making and technical considerations. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:854-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chen GH, Fu BS, Cai CJ, Lu MQ, Yang Y, Yi SH, Xu C, Li H, Wang GS, Zhang T. A single-center experience of retransplantation for liver transplant recipients with a failing graft. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1485-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Flemming JA, Kim WR, Brosgart CL, Terrault NA. Reduction in liver transplant wait-listing in the era of direct-acting antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2017;65:804-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Crivellin C, De Martin E, Germani G, Gambato M, Senzolo M, Russo FP, Vitale A, Zanus G, Cillo U, Burra P. Risk factors in liver retransplantation: a single-center experience. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:1110-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Torres-Quevedo R, Moya-Herraiz A, San Juan F, Rivera J, López-Andujar R, Montalvá E, Pareja E, De Juan M, Aguilera V, Berenguer M, Prieto M, Mir J. [Indications and results of liver retransplantation: experience with 1181 patients at the University Hospital La Fe]. Cir Esp. 2010;87:356-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Watt KD, Lyden ER, McCashland TM. Poor survival after liver retransplantation: is hepatitis C to blame? Liver Transpl. 2003;9:1019-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yerdel MA, Gunson B, Mirza D, Karayalçin K, Olliff S, Buckels J, Mayer D, McMaster P, Pirenne J. Portal vein thrombosis in adults undergoing liver transplantation: risk factors, screening, management, and outcome. Transplantation. 2000;69:1873-1881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 525] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Slater RR, Jabbour N, Abbass AA, Patil V, Hundley J, Kazimi M, Kim D, Yoshida A, Abouljoud M. Left renal vein ligation: a technique to mitigate low portal flow from splenic vein siphon during liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1743-1747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Akbulut S, Kayaalp C, Yilmaz M, Yilmaz S. Auxiliary reno-portal anastomosis in living donor liver transplantation: a technique for recipients with low portal inflow. Transpl Int. 2012;25:e73-e75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Silva MA, Jambulingam PS, Gunson BK, Mayer D, Buckels JA, Mirza DF, Bramhall SR. Hepatic artery thrombosis following orthotopic liver transplantation: a 10-year experience from a single centre in the United Kingdom. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:146-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jain A, Costa G, Marsh W, Fontes P, Devera M, Mazariegos G, Reyes J, Patel K, Mohanka R, Gadomski M, Fung J, Marcos A. Thrombotic and nonthrombotic hepatic artery complications in adults and children following primary liver transplantation with long-term follow-up in 1000 consecutive patients. Transpl Int. 2006;19:27-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |