Published online Feb 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i3.560

Peer-review started: November 14, 2019

First decision: December 23, 2019

Revised: December 24, 2019

Accepted: January 2, 2020

Article in press: January 2, 2020

Published online: February 6, 2020

Processing time: 83 Days and 8.9 Hours

Adult-onset still disease (AOSD) and hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) are two inflammatory diseases with very similar clinical manifestations. HPS is one of the most serious complications of AOSD and its risk of death is very high. It is difficult to identify HPS early in patients with AOSD, but early identification and proper treatment directly affects the prognosis.

A 39-year-old male showed a high spiking fever and myalgia. Laboratory data revealed elevated white blood cell, serum ferritin, and neutrophil percentage. However, his fever failed to relieve after a clear diagnosis of AOSD caused by pulmonary infection and treatment by antibiotics and corticosteroids; further laboratory data showed elevated serum ferritin, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and triglyceride, as well as liver abnormalities. Bone marrow smear showed hemophagocytosis. Secondary HPS was definitely diagnosed. The high fever disappeared and the laboratory findings returned to normal values after treatment by high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone and methotrexate.

For AOSD patients with high suspicion of HPS, active examination needs to be considered for early diagnosis, and timely using of adequate amount of corticosteroids is the key to reducing risk of HPS death.

Core tip: The clinical manifestations of hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) and adult-onset still disease (AOSD) are very similar. HPS is one of the most serious complications of AOSD and its risk of death is very high. For AOSD patients with high suspicion of HPS, bone marrow biopsies of the liver and spleen should be conducted to actively find pathological evidence. This would then enable clinicians to provide an early diagnosis and treatment strategy. Additionally, clinical symptoms and laboratory data should be taken into comprehensive consideration during treatment, to closely observe whether the disease is effectively controlled and adjust steroid dosage in time. If this is considered in the future, the occurrence of HPS could be avoided.

- Citation: Wang G, Jin XR, Jiang DX. Successful treatment of adult-onset still disease caused by pulmonary infection-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(3): 560-567

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i3/560.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i3.560

Adult-onset still disease (AOSD) is a multisystemic inflammatory disorder of unclear pathogenesis, characterized by spiking fever, evanescent rash, arthralgia, arthritis, sore throat, hepatosplenomegaly, neutrophilic leukocytosis and high serum ferritin (SF)[1]. Its prevalence is less than 1/100000[2]. Hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS), also called hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (itself referred to as HLH), is a life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome, characterized by the activation of macrophages and histiocytes with prominent hemophagocytosis, found in bone marrow and other reticuloendothelial systems[3]. The cardinal symptoms include high fever, pancytopenia, lymph node swelling, hepatosplenomegaly and elevated levels of SF.

The diagnosis of atypical HPS can be extremely difficult. On the one hand, HPS is always induced by AOSD. On the other hand, HPS and AOSD have several similar clinical features and pathogenic abnormalities[4]. Therefore, early identification of HPS in patients with AOSD is difficult, but it is important because early therapy directly affects the morbidity and mortality of patients. Herein, we report the case of a patient with severe AOSD and HPS, where the patient's condition improved thanks to early identification of HPS and active administration of high-dose therapy.

A 39-year-old Chinese man was admitted to our hospital due to a 13 d history of fever (Tmax 39.0+ °C) with productive cough.

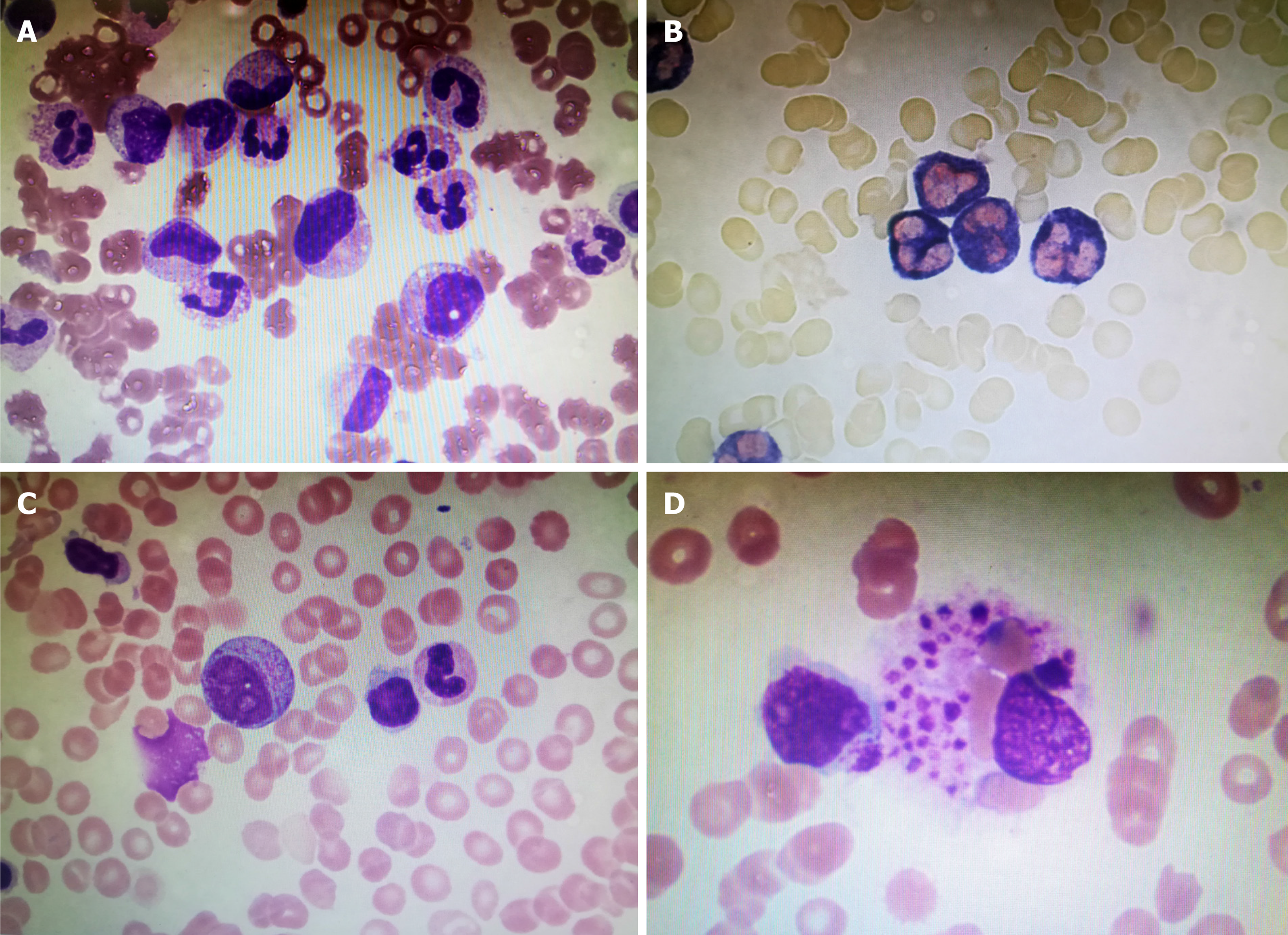

The patient was admitted to a local hospital 13 d prior due to a sudden fever with sore throat and myalgia. Chest-computed tomography (CT) detected mild inflammation in bilateral lower lobe and laboratory tests showed elevated levels of white blood cell (WBC) 34.8 × 109/L, neutrophil percentage (NE) 96.89%, platelet (PLT 329 × 109/L), C-reactive protein (CRP) 183 mg/L, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 58.0 mm/h. Additionally, anti-“O”-antibody (ASO) was positive (615.43 IU/mL), oropharyngeal swab culture was found positive for α-streptococcus, and the bone marrow smear showed white blood cells and neutrophils increased significantly with nuclear shift to the left, indicating infection (Figure 1A). All of this revealed severe inflammation, taking into consideration the patient’s infection with cocci.

The patient’s temperature returned to normal and the symptoms improved temporarily after giving empirical antibiotic therapy. This included levofloxacin, ceftriaxone, cefotiam, meropenem and azithromycin, as well as other anti-inflammatory and antipyretic treatments. However, the temperature raised again (up to 40 °C) after just a few hours, and skin rash presented on the chest and back, appearing or subsiding with body temperature rise or fall. Following further treatment with imipenoxinastatin, not only did the symptoms show no sign of improvement but sore throat and arthralgia occurred, without hair loss and photosensitization.

In total, the patient lost 8 kg of weight in the last half month.

There were no positive findings on past disease history.

There were no positive findings on family history.

Physical examination of the patient showed scattered skin rash on the chest and back, no palpable lymph nodes, and no abnormal findings in heart and lungs. Abdominal examination revealed the liver was not palpable but with slight splenomegaly.

Initial laboratory examinations on admission revealed elevated levels of WBC count 49.82 × 109/L with 88% neutrophils, platelet count 374 × 109/L, CRP 204 mg/L, ESR 66.0 mm/h, fibrinogen 4.87/L, procalcitonin (PCT) 21.94 ng/mL, and SF markedly elevated to 42703 ng/mL. The blood chemistry results showed alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 71 U/L and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 56 U/L. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and triglyceride (TG) were normal. Repeated sputum, blood and medullo cultures for fungi, bacteria and viruses were negative. An autoimmune screen was negative, with antinuclear antibody, dsDNA, rheumatoid factor, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody all being negative. All laboratory examination results are shown in Table 1.

| Laboratory parameter (measure) | Reference range | Before admission | Upon admission | During treatment | After treatment |

| WBC (109/L) | 4-10 | 34.8 | 49.82 | 2.82 | 7.86 |

| Neutrophil count (109/L) | 2-7 | - | 121 | 1.9 | 4.2 |

| NE (%) | 50-70 | 96.89 | 88.0 | 68.1 | 53.3 |

| Hb (g/L) | 120-160 | 127 | 121 | 98 | 106 |

| PLT (109/L) | 100-300 | 329 | 374 | 144 | 309 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0-8 | 183 | 204 | 83.3 | 1.9 |

| ESR (mm/L) | 0-15 | 58 | 66 | 24 | 5 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 0-0.49 | - | 21.94 | 0.32 | - |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 2.0-4.0 | - | 4.87 | - | 2.06 |

| SF (ng/mL) | 30-400 | - | 42703 | > 2000 | 764.4 |

| TG | 0.57-1.7 | - | 1.43 | 2.6 | 1.34 |

| LDH (U/L) | 114-240 | - | 458 | 637 | 151 |

| ALT (U/L) | 0-40 | - | 71 | 126 | 23 |

| AST (U/L) | 0-40 | - | 56 | 82 | 13 |

| NK cells (%) | 9.2-21.5 | - | 20.9 | 6.4 | 15.9 |

| ANA | Negative | - | Negative | - | - |

| RF (IU/mL) | Negative | - | Negative | - | Negative |

A positron emission tomography/CT scan was then performed to search for malignant tumors and hematologic disorders, but no abnormalities were found other than mild splenomegaly and mediastinal lymphadenitis. A CT scan revealed splenomegaly.

Laboratory tests showed leukopenia (WBC 2.82 × 109/L), lymphopenia (N 1.9 × 109/L), NE 68.1%, anemia (hemoglobin 98 g/L), PLT 144 × 109/L, increased ESR (24 mm/h), CRP 83.3 mg/L, SF > 2000 ng/mL, and an abnormality in their liver functions (ALT 126 U/L, AST 82 U/L). Besides, LDH (637 U/L) and TG (2.60 mol/L) were increased. Natural killer cells count was 6.4%. The bone marrow smear showed hemophagocytosis: Macrophages engulfing lymphocytes, erythrocytes and platelets (Figure 1B).

The final diagnosis of the presented case is AOSD caused by pulmonary infection-associated HPS.

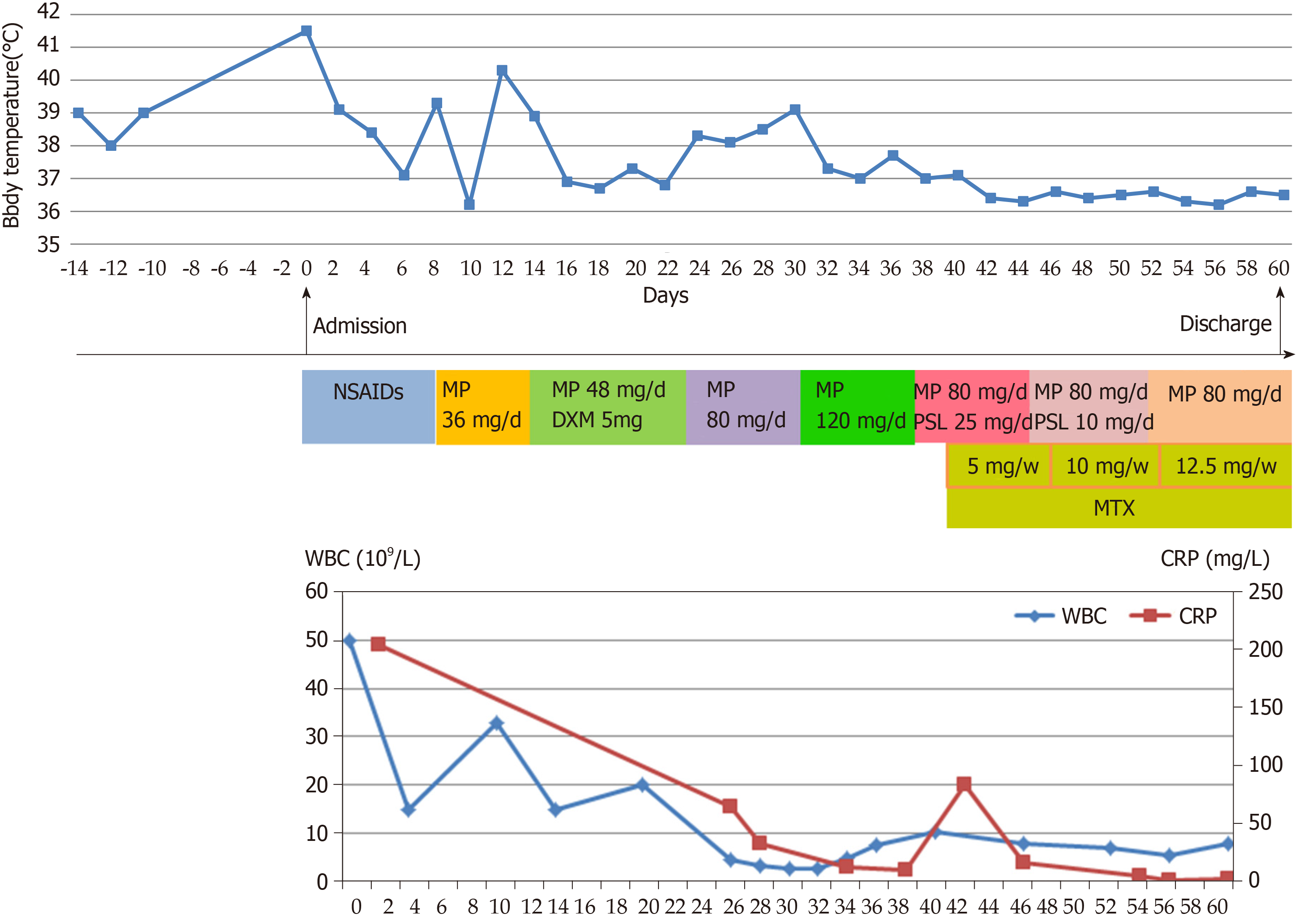

After admission, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were given to relieve symptoms and related examinations were performed. Once infections, hematological and solid organ malignancies, as well as connective tissue disease were excluded, AOSD was considered. After the diagnosis of AOSD was confirmed, the patient was managed with 80 mg/d methylprednisolone treatment for 7 d based on protecting liver function; with this treatment, his fever came down and the sore throat and myalgia were relieved. However, the persistent fever remained after 7 d of treatment. Laboratory tests showed an increased ESR (24 mm/h), CRP 83.3 mg/L and SF > 2000 ng/mL, and an abnormality in the liver functions (ALT 126 U/L, AST 82 U/L). Besides, there was increase in LDH (637 U/L) and TG (2.60 mol/L). Natural killer cells count was 6.4%. CT scan revealed splenomegaly. The bone marrow smear showed hemophagocytosis. HPS was then diagnosed, and treatment of high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (120 mg) was administered daily. The HPS did not recur and the prednisolone dose was slowly reduced, whilst methotrexate (MTX) 15 mg was added per week after.

The high fever disappeared, and blood tests performed after 1 wk showed WBC 7.86 × 109/L, N 4.2 × 109/L, NE 53.3%, hemoglobin 106 g/L, PLT 309 × 109/L, ESR 5 mm/h, CRP 1.9 mg/L, SF 764.4 ng/mL, ALT 23 U/L, AST 13 U/L, LDH 151 U/L, and TG 1.34 mol/L. The patient was discharged and all the laboratory findings returned to normal values (Figure 2). The patient was followed-up for a year after discharge from the hospital. There was no relapse of the AOSD or HPS. MTX was then discontinued, and the dose of oral prednisolone gradually reduced and maintained at 3 mg twice a day.

AOSD is a rare systemic auto-inflammatory disorder with unclear pathogenesis. It is a “cytokine storm”, with excessive proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-18, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interferon-γ[5]. These are all produced alongside the excessive activation of innate immunity, which triggers viral, bacterial and other pathogenic organisms[1,4]. It is characterized by spiking fever, arthralgia, rash, sore throat, neutrophil elevation, and hepatosplenomegaly. AOSD has a good prognosis and low mortality rate, but several rare and severe complications increase the mortality rate. A retrospective study found 26 deaths (2.75% mortality) among 932 AOSD patients, identified in 18 cohort studies published over 25 years. Of these, 14 deaths were from HPS[6], indicating HPS is one of the most serious complications of AOSD, with a high risk of death.

The HPS syndrome is a group of heterogeneous diseases, characterized by a hyperinflammatory state due to uncontrolled T cell, macrophage and histiocyte activation, accompanied by excessive cytokine production. HPS has been categorized as primary (which has an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern) or secondary (triggered by infectious, drug-induced, autoimmune or neoplastic conditions)[7,8]. Studies have found more than one underlying factor in nearly one-third of secondary HPS cases[9]. HPS is a rare but potentially life-threatening disease, and, although rare, it is not uncommon in AOSD. The most frequent etiology of HPS in all connective tissue diseases is AOSD, with an incidence of 12% to 14%, which is much higher than that for other rheumatic diseases[10-12]. Also, it is one of the most life-threatening complications, with mortality rates of 10% to 22%[9,12]. So, early recognition and prompt management is essential to significantly decrease mortality rates.

AOSD is an excessive autoimmune response triggered by certain bacterial or viral infections, acting on genetically-susceptible individuals. This patient’s initial examination showed ASO (+) and elevated WBC and NE. Oropharyngeal swab culture and bone marrow smear both indicated coccal infection. CT also detected mild inflammation in the bilateral lower lobe. The evidence of infection was obvious, so it was deduced that the fever was caused by infection. However, despite anti-infection treatment with sensitive antibiotics, the patient’s fever continued and a rash occurred. Senior broad-spectrum antibiotics were then administered for 7 d, but the fever still did not relieve. This forced us to reflect that the patient’s fever was not simply caused by infection. Further examinations suggested that the SF was high, PCT was normal, and infection, malignant tumors, hematologic disorders and other connective tissue diseases were excluded. According to the Yamaguchi standard[13], the patient was diagnosed with AOSD, and the fever and rash were relieved after treatment with high-dose corticosteroids. Given the above, the fever of this patient was eventually concluded to be caused by both infection and induced AOSD. It is thought that the pathogenesis of AOSD may occur by the activation of autoimmune responses triggered by streptococcal infection (as in this case), so the addition of a large high-dose of corticosteroid could control the disease.

The mechanism of underlying AOSD is not completely understood, but some scholars believe that lymphocyte and monocytes play an important role in its pathogenesis. High levels of ferritin, IL-8, IL-6, IL-18 and TNF-α in serum suggest a highly activated monocyte system in AOSD patients, and the continuous activation of the monocyte system may lead to the relatively rare but dangerous HPS in clinical practice[14-16]. After diagnosis of AOSD and treatment with high-dose glucocorticoids, the fever relieved. However, after 1 wk, spiking high fever (Tmax > 38.5 °C) suddenly appeared and SF, CRP and ESR elevated again. WBC and hemoglobin showed a decreasing trend, and liver enzyme and TG continued to rise. It was then that HPS (a complication of AOSD) was suspected. Bone puncture was performed again, and bone marrow smears suggested hemophagocytosis. The patient was diagnosed with HPS, referring to the 2004 HPS (HLH) diagnostic criteria (Table 2)[17]. Based on protecting liver function, the patient was given methylprednisolone (120 mg per d), followed by MTX weekly to suppress immunity. The fever soon came down and the laboratory findings showed the WBC, CRP, ESR, SF and TG reached the normal range after 1 wk. HPS did not recur and the methylprednisolone dose was subsequently reduced slowly.

| Diagnosis of HLH can be established if one of the two criteria below are met |

| 1 A molecular diagnosis consistent with HLH (i.e. reported mutations found in either PRF1 or MUNC13-4), or |

| 2 Diagnostic criteria for HLH are fulfilled (i.e. at least five of the eight criteria listed below are present) |

| (A) Persistent fever |

| (B) Splenomegaly |

| (C) Cytopenia (affecting ≥ 2 of 3 lineages in the peripheral blood) |

| (i) Hemoglobin < 90g/L (in infants < 4 wk: < 100g/L) |

| (ii) Platelets < 100 × 109/L |

| (iii) Neutrophils < 1.0 × 109/L |

| (D) Hypertriglyceremia and/or hypofibrinogenemia |

| (i) Fasting triglycerides ≥ 3.0 mmol/L (i.e. ≥ 265 mg/dL) |

| (ii) Fibrinogen ≤ 1.5g/L |

| (E) Hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, spleen or lymph nodes, no evidence of malignancy |

| (F) Serum ferritin ≥ 500 µg/L (i.e. 500 ng/mL) |

| (G) Low or absent natural killer cell activity (according to local laboratory reference) |

| (H) Increased serum sIL2Rα (according to local laboratory reference) |

The literature indicates that steroids, chemotherapeutic agents, and targeted biologics have all been successfully used to treat HPS; however, pulse steroids are considered to be the most important immediate treatment. The effect of biological agents, such as anakinra, is obvious; however, the therapeutic effect of tocilizumab is not clear. Immunosuppressants such as MTX, mycophenolate and cyclosporin are considered second-line drugs for secondary HPS because of their obvious side effects[18]. Therefore, proper use of corticosteroids is the key to effective treatment of secondary HPS on the basis of AOSD. After our patient was diagnosed with AOSD and given a large dose of glucocorticoids, his temperature went up and then down, followed by complications of HPS. We determined that the HPS was caused by insufficient glucocorticoid quantity, and that the daily dose of methylprednisolone (80 mg) at the beginning of the onset of AOSD could not control the inflammatory storm in vivo (resulting in the high levels of SF, CRP and ESR). This instead continuously stimulated the monocyte macrophagic system, leading to secondary HPS[14]. Therefore, patients can recover but from a higher dose of glucocorticoids, such as the treatment with methylprednisolone (120 mg per d) and MTX.

Our case was ultimately curable, and benefited from the early diagnosis of HPS and timely use of high-dose steroids therapy to control inflammatory storms. It should be reminded to clinicians that when unexplained high spiking fever, high SF, liver dysfunction, hypertriglyceridemia and cytopenia in two or more cell lineages progress during the course of an autoimmune disease, they should be aware of the possibility of HPS. As a result, repeated bone marrow, liver and spleen biopsy should be performed early and actively to search for pathological evidence of HPS. HPS in this case was induced by insufficient corticosteroids dosage, suggesting that early and adequate use of corticosteroids in the treatment of either AOSD or HPS may be beneficial.

In conclusion, the clinical manifestations of HPS and AOSD are very similar. For AOSD patients with high suspicion of HPS, bone marrow biopsies and biopsies of the liver and spleen should be conducted to actively find pathological evidence. These data would then enable clinicians to make an early diagnosis and treatment strategy. Additionally, from the successful treatment of this patient, if the clinical symptoms of AOSD patients become relieved after a high dose of corticosteroids but the laboratory data does not improve significantly, we should consider whether the patient's condition was effectively controlled and the dose of corticosteroids adjusted in a timely manner. If this is considered in the future, perhaps the occurrence of HPS could be avoided.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bolshakova GB S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Gerfaud-Valentin M, Jamilloux Y, Iwaz J, Sève P. Adult-onset Still's disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:708-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Magadur-Joly G, Billaud E, Barrier JH, Pennec YL, Masson C, Renou P, Prost A. Epidemiology of adult Still's disease: estimate of the incidence by a retrospective study in west France. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:587-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shi W, Duan M, Jie L, Sun W. A successful treatment of severe systemic lupus erythematosus caused by occult pulmonary infection-associated with hemophagocytic syndrome: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Maria AT, Le Quellec A, Jorgensen C, Touitou I, Rivière S, Guilpain P. Adult onset Still's disease (AOSD) in the era of biologic therapies: dichotomous view for cytokine and clinical expressions. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:1149-1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mehta B, Efthimiou P. Ferritin in adult-onset still's disease: just a useful innocent bystander? Int J Inflam. 2012;2012:298405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Priori R, Colafrancesco S, Picarelli G, Di Franco M, Valesini G. Adult-onset Still's disease: not always so good. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:142; author reply 143. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Dhote R, Simon J, Papo T, Detournay B, Sailler L, Andre MH, Dupond JL, Larroche C, Piette AM, Mechenstock D, Ziza JM, Arlaud J, Labussiere AS, Desvaux A, Baty V, Blanche P, Schaeffer A, Piette JC, Guillevin L, Boissonnas A, Christoforov B. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in adult systemic disease: report of twenty-six cases and literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:633-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | La Rosée P, Horne A, Hines M, von Bahr Greenwood T, Machowicz R, Berliner N, Birndt S, Gil-Herrera J, Girschikofsky M, Jordan MB, Kumar A, van Laar JAM, Lachmann G, Nichols KE, Ramanan AV, Wang Y, Wang Z, Janka G, Henter JI. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133:2465-2477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 108.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383:1503-1516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 788] [Cited by in RCA: 960] [Article Influence: 87.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Arlet JB, Le TH, Marinho A, Amoura Z, Wechsler B, Papo T, Piette JC. Reactive haemophagocytic syndrome in adult-onset Still's disease: a report of six patients and a review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1596-1601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fukaya S, Yasuda S, Hashimoto T, Oku K, Kataoka H, Horita T, Atsumi T, Koike T. Clinical features of haemophagocytic syndrome in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases: analysis of 30 cases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:1686-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hot A, Toh ML, Coppéré B, Perard L, Madoux MH, Mausservey C, Desmurs-Clavel H, Ffrench M, Ninet J. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in adult-onset Still disease: clinical features and long-term outcome: a case-control study of 8 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010;89:37-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yamaguchi M, Ohta A, Tsunematsu T, Kasukawa R, Mizushima Y, Kashiwagi H, Kashiwazaki S, Tanimoto K, Matsumoto Y, Ota T. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still's disease. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:424-430. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Lerkvaleekul B, Vilaiyuk S. Macrophage activation syndrome: early diagnosis is key. Open Access Rheumatol. 2018;10:117-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Schulert GS, Grom AA. Pathogenesis of macrophage activation syndrome and potential for cytokine- directed therapies. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:145-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Put K, Avau A, Brisse E, Mitera T, Put S, Proost P, Bader-Meunier B, Westhovens R, Van den Eynde BJ, Orabona C, Fallarino F, De Somer L, Tousseyn T, Quartier P, Wouters C, Matthys P. Cytokines in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: tipping the balance between interleukin-18 and interferon-γ. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:1507-1517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski J, Janka G. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3075] [Cited by in RCA: 3599] [Article Influence: 199.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Mehta B, Kasturi S, Teruya-Feldstein J, Horwitz S, Bass AR, Erkan D. Adult-Onset Still's Disease and Macrophage-Activating Syndrome Progressing to Lymphoma: A Clinical Pathology Conference Held by the Division of Rheumatology at Hospital for Special Surgery. HSS J. 2018;14:214-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |