Published online Feb 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i3.552

Peer-review started: July 12, 2019

First decision: September 9, 2019

Revised: October 13, 2019

Accepted: October 30, 2019

Article in press: October 30, 2019

Published online: February 6, 2020

Processing time: 219 Days and 19.5 Hours

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) enterocolitis presenting in the form of pancolitis or involving the small and large intestines in an immunocompetent patient is rarely encountered, and CMV enterocolitis presenting with a serious complication, such as toxic megacolon, in an immunocompetent adult has only been reported on a few occasions.

We describe the case of a 70-year-old male with no history of inflammatory bowel disease or immunodeficiency who presented with toxic megacolon and subsequently developed massive hemorrhage as a complication of CMV ileo-pancolitis. The patient was referred to our institute for abdominal pain and distension. Abdominal X-ray showed marked dilatation of ileum and whole colon without air-fluid level, and sigmoidoscopy with biopsy failed to reveal any specific finding. After 7 d of conservative treatment, massive hematochezia developed, and he was diagnosed to have CMV enterocolitis by colonoscopy with biopsy. Although the diagnosis of CMV enterocolitis was delayed, the patient was treated successfully by repeat colonoscopic decompression and antiviral therapy with intravenous ganciclovir.

This report cautions that CMV-induced colitis should be considered as a possible differential diagnosis in a patient with intractable symptoms of enterocolitis or megacolon of unknown cause, even when the patient is non-immunocompromised.

Core tip: Cytomegalovirus (CMV) enterocolitis presenting as toxic megacolon in an immunocompetent patient is rarely encountered. We report the case of a 70-year-old male with a non-immunocompromised state that presented with toxic megacolon and subsequently developed massive hemorrhage as a complication of CMV ileo-pancolitis. Although the diagnosis was delayed until massive hematochezia developed, the patient was treated successfully by repeat colonoscopic decompression and intravenous ganciclovir. A high degree of clinical suspicion is required to diagnose CMV enterocolitis, especially in immunocompetent patients, and this condition should be considered as a possible differential diagnosis in patients with intractable symptoms of enterocolitis or megacolon of unknown cause.

- Citation: Cho JH, Choi JH. Cytomegalovirus ileo-pancolitis presenting as toxic megacolon in an immunocompetent patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(3): 552-559

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i3/552.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i3.552

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a highly prevalent virus with a worldwide distribution, and CMV infections in healthy adults are usually asymptomatic or cause a mildly infectious mononucleosis-like syndrome. CMV then usually becomes dormant until reactivation in patients with a severely immunocompromised status, and may manifest as invasive CMV disease with a wide range of manifestations, most commonly colorectal infection with hemorrhagic ulceration. However, gastrointestinal involvement with CMV infection is uncommon in immunocompetent individuals.

CMV colitis can be complicated by massive hemorrhage, acute colonic pseudo-obstruction, toxic megacolon, and perforation[1]. However, CMV colitis has often been missed by clinical physicians in immunocompetent patients presenting with these serious complications[2]. Furthermore, CMV colitis presenting as megacolon in an immunocompetent adult has rarely been reported.

Here we report on a case of CMV ileo-pancolitis presenting as toxic megacolon and subsequent massive hemorrhage in an immunocompetent patient. This case highlights that this condition should be considered as a possible differential diagnosis in even non-immune compromised patients with megacolon or intestinal pseudo-obstruction of unknown cause.

Abdominal pain and constipation.

A 70-year-old man was referred to our hospital due to generalized abdominal pain and reduced stool passage over the previous 2 wk. He reported no melena or body weight loss.

He had no history of abdominal surgery and no notable medical history.

He had no specific personal or family history.

The patient’s temperature was 38.4 °C. His physical examination revealed a distended abdomen with tenderness and hypoactive bowel sounds.

Laboratory testing upon admission revealed; low hemoglobin (11.2 g/dL; normal, 13-17 g/dL), neutrophilic leukocytosis (white blood cell, 12200 cells/mL; normal, 3900-10600 cells/mL; neutrophils 88.7%), high C-reactive protein (CRP; 29.1 mg/dL; normal, < 0.5 mg/dL), high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (101 mm/h; normal, < 20 mm/h), and negativity for anti-nuclear antibody, human immunodeficiency virus. Other laboratory findings included normal renal, hepatic and thyroid function, and normal electrolyte results. Stool cultures for Clostridium difficile and enteric pathogens and blood cultures were all negative.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and X-ray imaging showed marked diffuse dilatation of the ileum and entire colon but no definite obstructive lesion (Figure 1). Minimum colon diameter was 7 cm, which was consistent with a diagnosis of megacolon.

Sigmoidoscopy revealed diffuse ulcerative and hyperemic mucosa with friability and edema, and a large amount of fecal matter, which prevented visualization of the colon wall. Endoscopic biopsy specimens indicated only acute and chronic inflammation, erosion, and necrotic debris. Based on the initial laboratory, radiologic and endoscopic findings, ciprofloxacin and metronidazole antibiotic therapy with supportive care involving nil-per-os, total parenteral nutrition, nasogastric decompression, and correction of fluid and electrolyte abnormalities was started under a provisional diagnosis of severe acute enterocolitis with toxic megacolon of unknown cause. Although the patient remained febrile with abdominal distension despite antibiotic treatment and two additional repeated colonoscopic decompressions, we postponed the surgical option and continued supportive treatment because clinical signs and symptoms did not worsen.

On hospital day 7, he began passing approximately 1 liter of fresh blood per rectum and hemoglobin fell from 11.0 g/dL to 7.1 g/dL, which required aggressive packed red blood cell transfusion, fluid resuscitation, and intravenous vasopressors and inotropes to maintain hemodynamic stability. After immediate vigorous volume resuscitation, emergent colonoscopy revealed multiple deep ulcers on whole colon. Although it was difficult to define the lesion and bleeding focus because the endoscopic visual field was limited by large amounts of blood and blood clots, active bleeding could not be found.

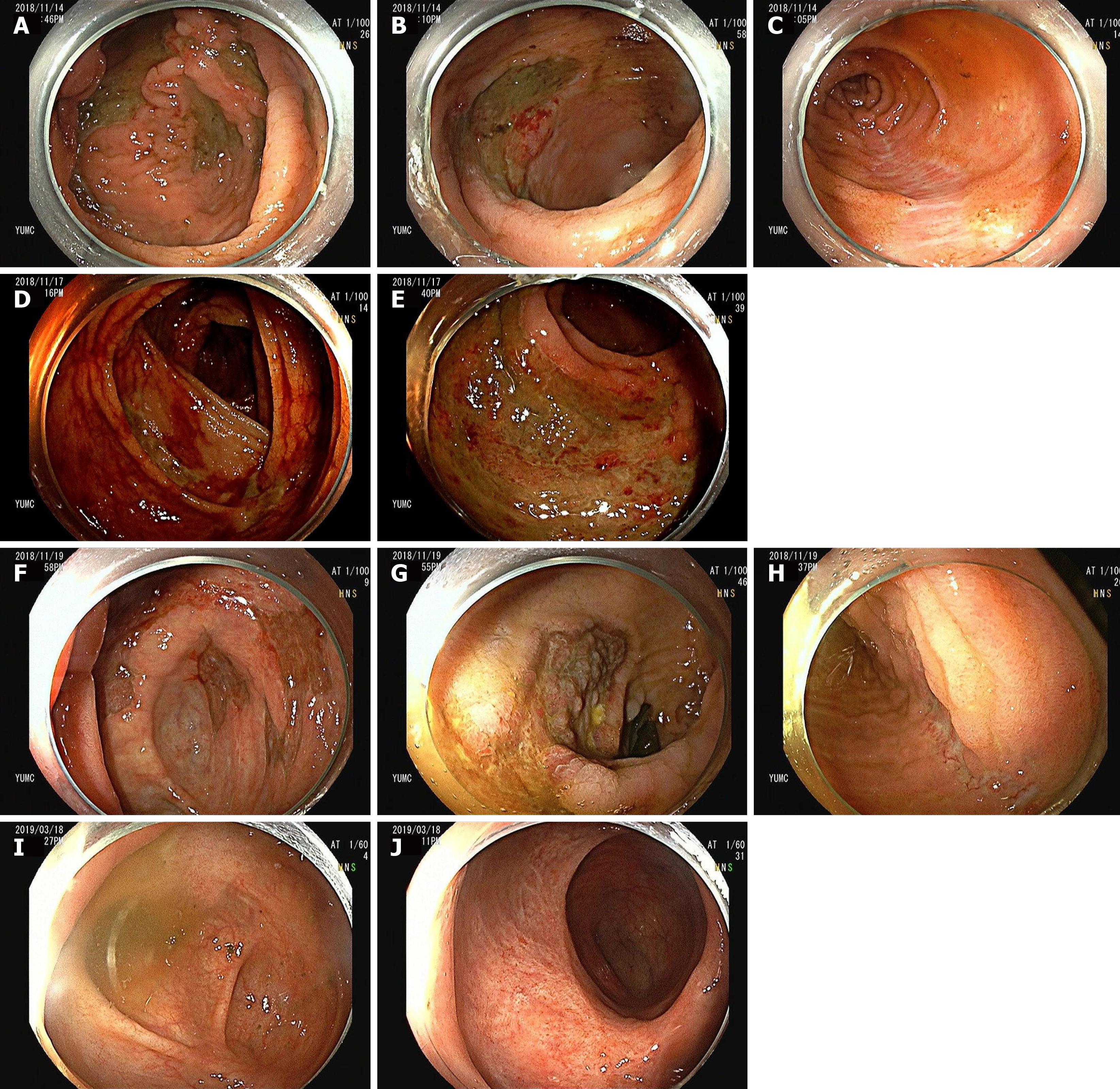

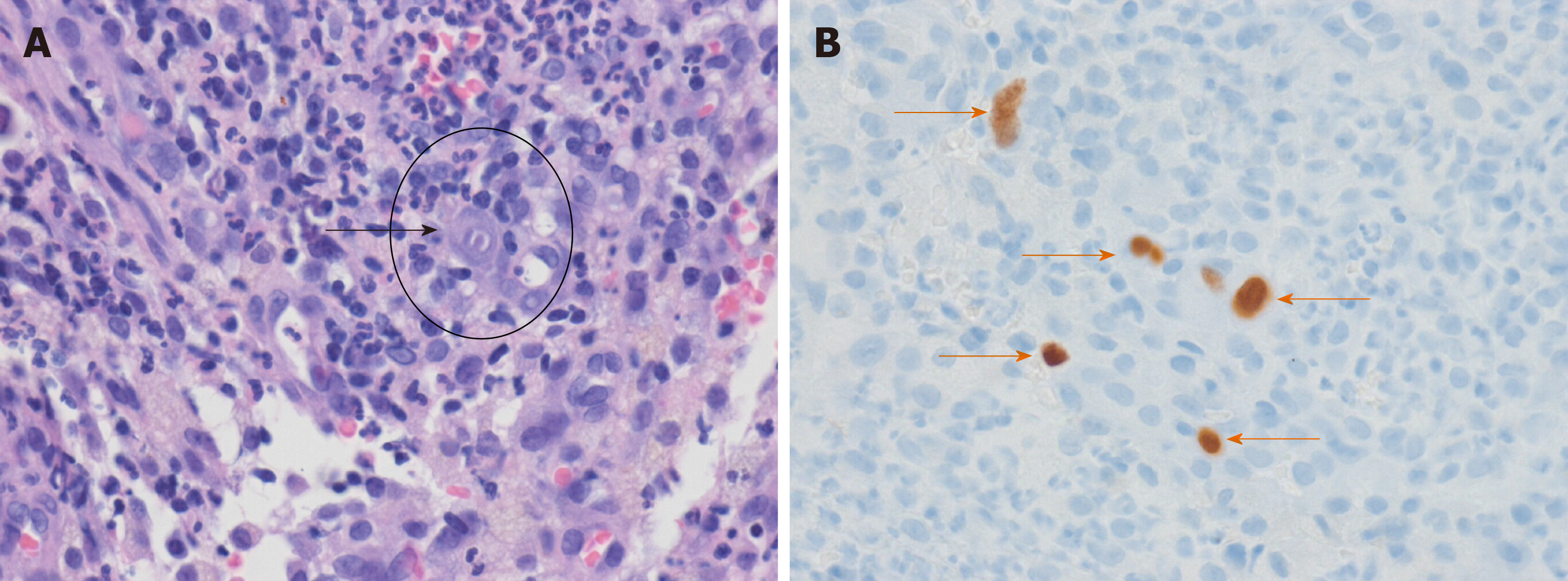

On hospital day 8, repeat colonoscopy revealed huge, variably-sized multiple diffuse deep ulcers with exudate and multiple ulcer scars in nearly the entire colon (predominantly affecting cecum to ascending colon, and sigmoid colon to rectum) (Figure 2A-C). When the colonoscope was intubated more proximally 50 cm from the ileocecal valve, multiple healing stage ulcers were observed in the distal ileum. These lesions may have affected the more proximal portion from the site we could observe via colonoscope. Histopathology of the biopsy at ascending colon and rectum showed acute and chronic inflammation and ulcers. In addition, enlarged cells with intranuclear inclusion bodies were observed in the biopsy specimens (Figure 3A). These epithelial cells were positive for monoclonal anti-CMV antibody on immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 3B), confirming the diagnosis of CMV colitis. CMV viral load in whole-blood samples as determined by real time PCR was 3360 DNA copies/mL, and serum CMV IgG and IgM were seropositive and seronegative, respectively. Repeat colonoscopy performed due to the persistent, intermittent large amount of hematochezia for 1 wk after the first hematochezia event (Figure 2D and 2E).

Cytomegalovirus ileo-pancolitis complicated by toxic megacolon and massive intestinal bleeding.

Antiviral therapy with intravenous ganciclovir (250 mg every 12 h) was started on day 11, and subsequently, the frequency and amount of lower gastrointestinal bleeding gradually reduced.

On hospital day 14 (7 d after the first hematochezia event), follow-up colonoscopy revealed huge, variably-sized, multiple, diffuse healing ulcers with pinkish granulation tissue bases, multiple ulcer scars on colon (Figure 2F-H), and multiple healing stage ulcers in distal ileum. Abdominal X-ray showed much improvement of paralytic ileus and megacolon. Furthermore, laboratory findings were improved and abdominal pain and fever had subsided. Therefore, oral feeding was resumed, and subsequently, the patient continued to improve. Laboratory data after 3 wk on ganciclovir revealed an undetectable CMV viral load, and he was discharged without maintenance therapy on hospital day 31 after completing his 3-wk antiviral course. Last follow-up colonoscopy was performed at an outpatient department 2 mo after discharge, and showed near complete healing of colon (Figure 2I and 2J) and ileal ulcers.

Gastrointestinal involvement by CMV usually occurs secondary to the reactivation of latent infection in immunosuppressed patients, such as those that undergo organ or bone marrow-transplantation, are diagnosed with acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and those on immunosuppressant medication (e.g., anti-tumor necrosis factor antibodies, steroids) or chemotherapeutic agents. Although gastrointestinal involvement is uncommon in immunocompetent patients, CMV colitis is being increasingly recognized in apparently immunocompetent patients with immunomodulating factors, such as an advanced age, pregnancy, chronic renal failure, coronary artery disease, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, blood transfusion, or prolonged stay in an intensive care unit[2-10]. The possibility of CMV colitis development in immunocompetent patients has often been overlooked by clinical physicians. In the current case, we did not consider CMV colitis in the differential diagnosis until massive hematochezia developed. A strong clinical suspicion is required to diagnose CMV colitis in immunocompetent patients in addition to confirmative findings from different diagnostic methods, including CMV serology and endoscopic and histopathologic evaluations.

In a meta-analysis of 43 immunocompetent patients with CMV colitis, 34 (77.3%) were more than 55 years old with co-existent comorbidities (77.3%), and 19 (44.2%) presented with conditions that induced immune system alterations, such as pregnancy, renal failure, diabetes mellitus, or untreated non-hematological malignancy[5]. The higher incidence of this pathology in older immunocompetent patients is likely a reflection of an age-related weakening of the immune system, as extensive studies have demonstrated aging is associated with declines in cellular and humoral immunities[11]. Furthermore, impaired cytokine regulation and fragile integrity of mucosal immunity are also considered to contribute to relative immunodeficiencies in the elderly and to predispose them to various infectious and inflammatory diseases[11]. However, the higher prevalence of comorbidities in the elderly provides another explanation for the predominance of older patients.

CMV target organs include the gastrointestinal tract, lung, retina, liver, and central nervous system. CMV can infect the gastrointestinal tract from esophagus to rectum, though the most commonly affected areas are colon and rectum; other locations such as the small intestine are less commonly affected. In addition, it is rare that CMV colitis manifests as pancolitis. Although some cases have been reported in immunocompromised patients with steroid-refractory inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) colitis, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or in patients on immunosuppressive agents[12-14], it is rare that CMV colitis presents in the form of pancolitis in an immunocompetent patient. In fact, a literature search identified only one case report of simultaneous small and large intestine involvement in an immunocompetent patient in the English literature database[15]. Thus, the described case of CMV ileo-pancolitis in an immunocompetent patient is extremely rare, although it should be added that the pathologic examination was conducted only on the large intestine.

CMV colitis may lead to clinical symptoms such as diarrhea, fever, and abdominal pain and may be complicated by hemorrhage or perforation[16,17] and rarely, be associated with toxic megacolon and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction, especially in immune compromised hosts. Only a few cases report toxic megacolon combined with CMV colitis, and all of which were in varying degrees of immunosuppression caused by renal allograft, AIDS, ulcerative colitis, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease being treated with steroid therapy[18-24]. In our case, despite a non-immune compromised status, CMV enterocolitis initially presented with symptoms and signs, such as abdominal pain and distension with tenderness, fever, marked distension of large intestine loops on abdominal X ray and CT images, and a high serum CRP level, compatible with toxic megacolon. Among the aggravating factors of IBD, CMV infection is a major cause of concern and often manifests as toxic megacolon[20,25]. Two hypotheses regarding the pathophysiology have been suggested[26], that is, destruction of myenteric plexus and muscle propria of the colon wall, and excessive use of anticholinergic drugs and sleeping pills. Our patient had no history of IBD and no history of drug use, such as of anticholinergics or hypnotics, which can cause acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Furthermore, symptoms and signs of toxic megacolon improved after antiviral therapy, and thus, we concluded that toxic megacolon in our patient was probably caused by CMV colitis itself.

Toxic megacolon is one of the most dreaded complications of uncontrolled CMV colitis. The rate of toxic megacolon in CMV colitis is approximately 13%[1], and its mechanism remains unknown. One possible mechanism for the colonic dilatation observed in toxic megacolon is that inflamed colonic mucosa releases inflammatory mediators and bacterial products, which lead sequentially to induce nitric oxide synthase and increase the generation of excessive nitric oxide[18]. It is not easy to improve the clinical course of CMV colitis complicated by megacolon in immunocompromised patients, and even when an antiviral therapy is combined with extensive colonic resection, mortality remains high[21]. Due to a sparsity of reports on the clinical course of immunocompetent patients with CMV colitis complicated by megacolon, the proper management of these patients remains uncertain. In one case report about CMV colitis with megacolon, conservative management with colonoscopic decompression combined with antiviral agent resulted in a favorable short-term outcome[19]. In our patient, CMV colitis with toxic megacolon was treated by repeated colonoscopic decompression, ganciclovir, and conservative treatment, and despite several episodes of massive hematochezia during hospitalization, the patient achieved full recovery, which suggests that conservative management without surgical intervention may be appropriate in immunocompetent patients with megacolon. We believe this rationale is supported by the presence of a relatively robust immune system and resultant ability to recover. However, a larger number of similar cases are required to evaluate the efficacy of this treatment.

The treatments of choice for CMV infection are antiviral drugs, such as ganciclovir or foscarnet. However, in a meta-analysis, patients aged less than 55 years without a concomitant disease achieved spontaneous remission[5], which suggests that in some specific immunocompetent patients, antiviral therapy might not be necessary and concurs with the conclusions of other authors[17]. However, in our patient, despite an immunocompetent status, CMV infection presented as extensive enterocolitis involving the distal ileum and the entire colon complicated by toxic megacolon and massive intestinal bleeding, and recovery was attributed to ganciclovir. In the present case, given the severity of the clinical picture and the absence of alternative diagnosis, it seems evident that the correct attitude was to treat by ganciclovir (in the absence of contraindication) without delay, what has been done successfully.

The described case illustrates that CMV enterocolitis should be considered as a possible differential diagnosis in an elderly patient with symptoms of enterocolitis or megacolon of unknown cause, even when the patient has no history of immunosuppressive disease or therapy. Colonoscopy and histopathologic evaluation of mucosal biopsies are essential for the diagnosis of CMV colitis, and a high degree of clinical suspicion is required when a patient being treated conservatively fails to improve. Early suspicion and diagnosis are essential, and early antiviral treatment should be considered especially in severe CMV enterocolitis with a potentially fatal complication such as toxic megacolon or massive hemorrhage.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Osawa S, Pozzetto B S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Klauber E, Briski LE, Khatib R. Cytomegalovirus colitis in the immunocompetent host: an overview. Scand J Infect Dis. 1998;30:559-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chan KS, Yang CC, Chen CM, Yang HH, Lee CC, Chuang YC, Yu WL. Cytomegalovirus colitis in intensive care unit patients: difficulties in clinical diagnosis. J Crit Care. 2014;29:474.e1-474.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Harano Y, Kotajima L, Arioka H. Case of cytomegalovirus colitis in an immunocompetent patient: a rare cause of abdominal pain and diarrhea in the elderly. Int J Gen Med. 2015;8:97-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chen YM, Hung YP, Huang CF, Lee NY, Chen CY, Sung JM, Chang CM, Chen PL, Lee CC, Wu YH, Lin HJ, Ko WC. Cytomegalovirus disease in nonimmunocompromised, human immunodeficiency virus-negative adults with chronic kidney disease. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2014;47:345-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Galiatsatos P, Shrier I, Lamoureux E, Szilagyi A. Meta-analysis of outcome of cytomegalovirus colitis in immunocompetent hosts. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:609-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ko JH, Peck KR, Lee WJ, Lee JY, Cho SY, Ha YE, Kang CI, Chung DR, Kim YH, Lee NY, Kim KM, Song JH. Clinical presentation and risk factors for cytomegalovirus colitis in immunocompetent adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:e20-e26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Siciliano RF, Castelli JB, Randi BA, Vieira RD, Strabelli TM. Cytomegalovirus colitis in immunocompetent critically ill patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;20:71-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | You DM, Johnson MD. Cytomegalovirus infection and the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:334-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hasegawa T, Aomatsu K, Nakamura M, Aomatsu N, Aomatsu K. Cytomegalovirus colitis followed by ischemic colitis in a non-immunocompromised adult: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:3750-3754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bernard S, Germi R, Lupo J, Laverrière MH, Masse V, Morand P, Gavazzi G. Symptomatic cytomegalovirus gastrointestinal infection with positive quantitative real-time PCR findings in apparently immunocompetent patients: a case series. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:1121.e1-1121.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schmucker DL, Heyworth MF, Owen RL, Daniels CK. Impact of aging on gastrointestinal mucosal immunity. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:1183-1193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kishore J, Ghoshal U, Ghoshal UC, Krishnani N, Kumar S, Singh M, Ayyagari A. Infection with cytomegalovirus in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence, clinical significance and outcome. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:1155-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Woywodt A, Choi M, Schneider W, Kettritz R, Göbel U. Cytomegalovirus colitis during mycophenolate mofetil therapy for Wegener's granulomatosis. Am J Nephrol. 2000;20:468-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Roskell DE, Hyde GM, Campbell AP, Jewell DP, Gray W. HIV associated cytomegalovirus colitis as a mimic of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1995;37:148-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sakamoto I, Shirai T, Kamide T, Igarashi M, Koike J, Ito A, Takagi A, Miwa T, Kajiwara H. Cytomegalovirus enterocolitis in an immunocompetent individual. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:243-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Buckner FS, Pomeroy C. Cytomegalovirus disease of the gastrointestinal tract in patients without AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:644-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shrestha BM, Parton D, Gray A, Shephard D, Griffith D, Westmoreland D, Griffin P, Lord R, Salaman JR, Moore RH. Cytomegalovirus involving gastrointestinal tract in renal transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 1996;10:170-175. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Orloff JJ, Saito R, Lasky S, Dave H. Toxic megacolon in cytomegalovirus colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:794-797. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Beaugerie L, Ngô Y, Goujard F, Gharakhanian S, Carbonnel F, Luboinski J, Malafosse M, Rozenbaum W, Le Quintrec Y. Etiology and management of toxic megacolon in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:858-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kotanagi H, Fukuoka T, Shibata Y, Yoshioka T, Aizawa O, Saito Y, Koyama K, Otaka M, Chiba M, Saito M. A case of toxic megacolon in ulcerative colitis associated with cytomegalovirus infection. J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:501-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Machens A, Bloechle C, Achilles EG, Bause HW, Izbicki JR. Toxic megacolon caused by cytomegalovirus colitis in a multiply injured patient. J Trauma. 1996;40:644-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sheth SG, LaMont JT. Toxic megacolon. Lancet. 1998;351:509-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mukhopadhya A, Samal SC, Patra S, Eapen CE, Abraham A, Thomas PP, Chandy GM. Toxic megacolon in a renal allograft recipient with cytomegalovirus colitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2001;20:114-115. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Shimada Y, Iiai T, Okamoto H, Suda T, Hatakeyama K, Honma T, Ajioka Y. Toxic megacolon associated with cytomegalovirus infection in ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1107-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Berk T, Gordon SJ, Choi HY, Cooper HS. Cytomegalovirus infection of the colon: a possible role in exacerbations of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:355-360. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Kirsner JB, Shorter RG. Inflammatory bowel disease. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger Co 1975; 210-211. |