Published online Oct 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4676

Peer-review started: April 30, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Revised: August 1, 2020

Accepted: August 26, 2020

Article in press: August 26, 2020

Published online: October 6, 2020

Processing time: 150 Days and 17.5 Hours

The common treatment for hydrocephalus is insertion of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Shunt tube displacement is one of the common complications. Most shunt tube displacements occur in children and has a reportedly lower incidence in adults.

This study reports an adult patient (male, 56 years) who suffered from intracranial aneurysm and subarachnoid hemorrhage and underwent aneurysm clipping following hospitalization. One month post onset of the disease, the patient underwent ventriculoperitoneal shunt due to hydrocephalus. The peritoneal end of the shunt tube was displaced in the peritoneal cavity 9 years after the aneurysm clipping. The peritoneal end of the shunt tube was removed and ventriculoperitoneal shunt was re-performed after anti-inflammatory treatment.

Shunt tube displacement has a low incidence in adults. In order to avoid shunt tube displacement, there is a need to summarize its causative factors and practice personalized medicine.

Core Tip: There is a certain incidence of shunt tube displacement in adults. We should summarize the related factors for shunt tube displacement to avoid or reduce its occurrence, and make individualized treatment according to the characteristics of each patient.

- Citation: Liu J, Guo M. Displacement of peritoneal end of a shunt tube to pleural cavity: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(19): 4676-4680

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i19/4676.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4676

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt is the most commonly used method for the treatment of hydrocephalus, but many complications may occur following the insertion of the shunt. The commonly reported complications include infection, shunt blockage, hypersensitivity, abdominal cyst formation, ascites, and shunt tube displacement, among others[1]. Most of shunt tube displacements are reported in children. The incidence is low in adults and relatively few cases have been reported. This study reports a case of displacement of the peritoneal end of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt tube to the pleural cavity in an adult patient with hydrocephalus.

A 56-year-old male patient presented with fever, decline of memory, pain in the right chest, and unstable walking for five days.

The patient suffered from an aneurysm with subarachnoid hemorrhage and underwent aneurysm clipping in Department of Neurosurgery at The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University on July 27, 2010. One month after the surgery, he underwent ventriculoperitoneal shunt due to hydrocephalus, and the patient recovered well. On March 25, 2019, the patient reported fever, decline of memory, pain in the right chest, and unstable walking.

The patient had been in good health.

The patient had an appearance of chronic disease, body temperature around 38 ˚C, normal orientation, poor memory, and weak respiratory sound in the right lung.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed that the number of cells was 82 × 106 cells/L, glucose level was 1.71 mmol/L, chloride was 98 mmol/L, and total protein was 891 mg/L. No bacteria were observed in CSF upon culture. The peritoneal end was surgically excised and the end was ligated. The patient was administered anti-inflammatory treatment for the following 10 d (ceftriaxone sodium, 2 g/time, Q12h; vancomycin 0.5 g/time, Q8h). On April 3, the CSF was re-examined, which showed that the number of cells was 8 × 106 cells/L, glucose was 2.69 mmol/L, chloride was 125 mmol/L, and total protein was 341 mg/L.

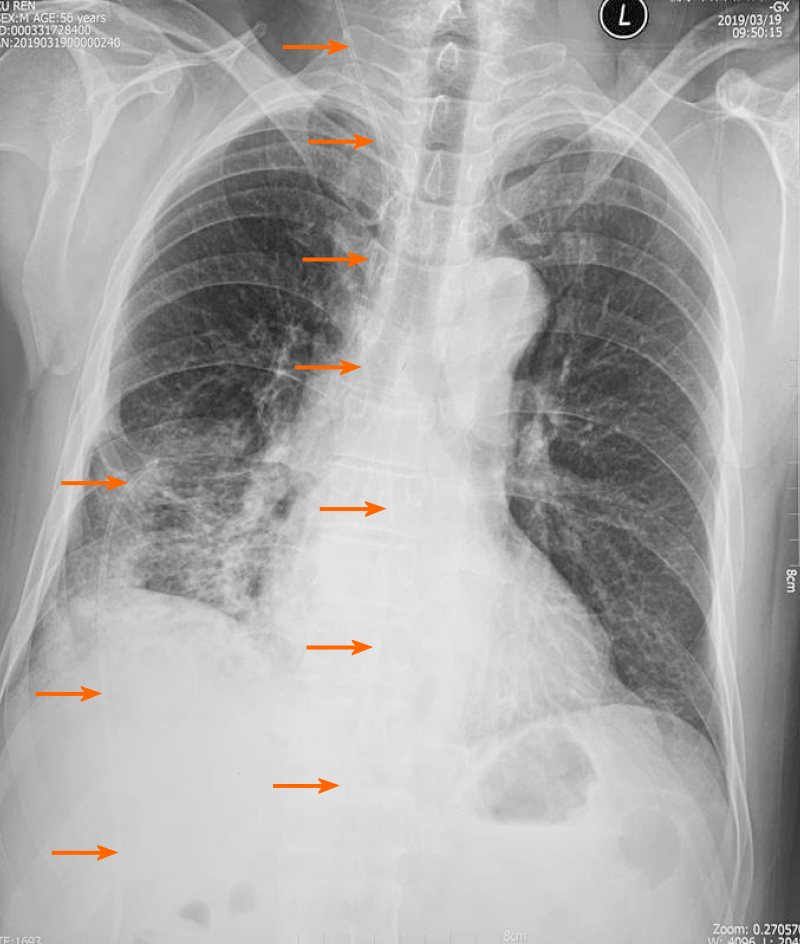

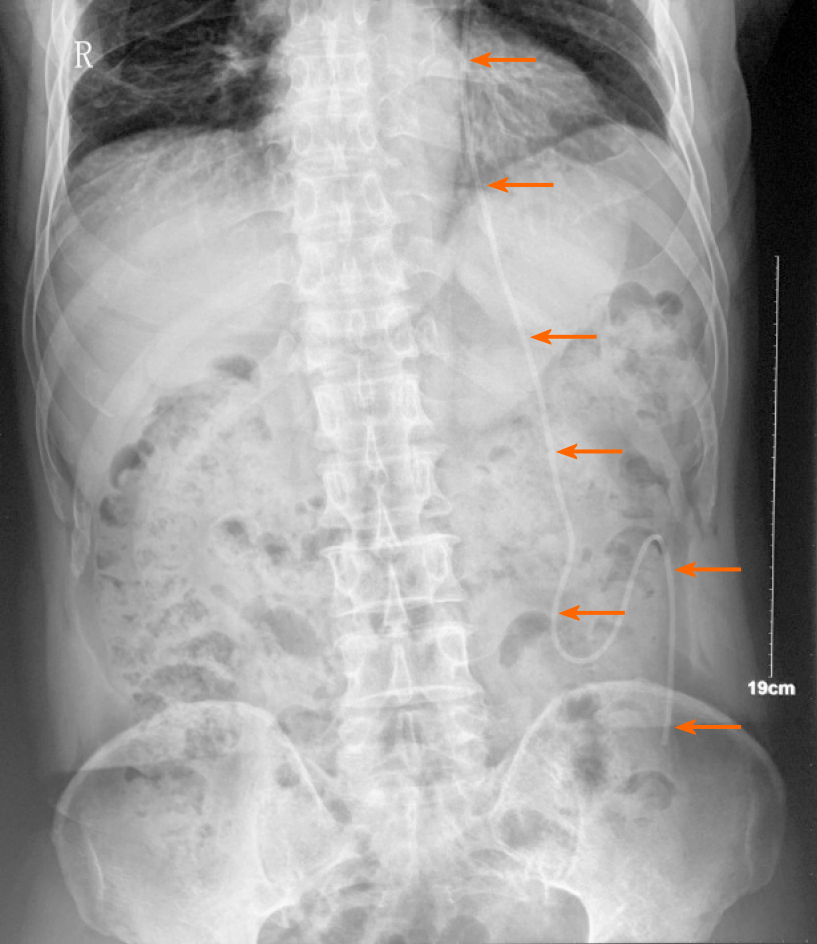

X-ray examination before operation revealed that the peritoneal end of the shunt tube had moved to the pleural cavity, resulting in pulmonary inflammation (Figure 1). An X-ray image after operation confirmed the shunt location in the abdominal cavity (Figure 2).

Displacement of the peritoneal end of the shunt tube to pleural cavity.

Ventriculoperitoneal shunt was re-performed after inflammation subsided on April 3, 2019.

The patient is recovering well and has no abnormal symptoms so far.

The displacement of the peritoneal end of the shunt tube after ventriculoperitoneal shunt is one of the common complications, but the reasons are still elusive. There are few hypotheses that partly explain the shunt tube displacement. Akyüz et al[2] reported that when the peritoneal end of the shunt tube is attached to the nearby organs or body wall, it will induce an inflammatory reaction, and the distal end of the catheter will gradually protrude outward. Sridhar et al[3] suggested that the distal migration of the shunt tube might be caused by the use of rigid material, which was supported by the observation that the use of a softer shunt tube did reduce the incidence of shunt tube displacement[4]. Additionally, some authors speculated that the distal penetration of the shunt tube through the body wall might be caused by local wound dehiscence, low patient immunity, improper surgical techniques, or dermal ischemic necrosis[5,6]. Other factors that lead to the distal migration of shunt tube may include the age of the patient and the length of the shunt tube in the abdominal cavity. Most of them occur in pediatric patients. It is probably a consequence of softer organs and tissues in children which are vulnerable to rupture.

There are three types of shunt tube displacement of the peritoneal end: Internal displacement, external displacement, and mixed displacement[7]. The intrathoracic migration of peritoneal shunt tube can be divided into two types: Supra-diaphragm and trans-diaphragm migration[8]. The subject of this study had a 9-year history since the last ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery. In combination with chest X-ray images, considering the end of the shunt tube at the upper edge of the liver, the long-term stimulation of the upper hepatic diaphragm may have led to the diaphragm damage. The peritoneal end of the shunt tube thus migrated to the pleural cavity, leading to an inflammatory response in the lungs. At the same time, the drainage of the shunt tube was blocked, causing hydrocephalus symptoms to reappear.

A variety of clinical manifestations can occur after the shunt is displaced. The treatment strategies, thus, need to be personalized. For patients with shunt tube displacement of the peritoneal end, it has been reported that the displaced shunt can be re-inserted directly into the abdominal cavity with the help of laparoscopic method[9]. Some scholars have proved that the use of laparoscopy to treat intraperitoneal complications after intraventricular shunting of the ventricle has the advantages of shorter operation time, less trauma, and reduced intestinal damage and adhesion, among others[10,11]. This patient had fever when admitted to the hospital, and the cerebrospinal fluid test showed abnormal cells, which did not rule out the possibility of pulmonary inflammation retrogradely resulting in intracranial infection. Therefore, the displaced shunt tube was not directly moved back to the abdominal cavity. The shunt tube was removed with subsequent anti-inflammatory treatment. After the number of cells in cerebrospinal fluid cells was normal, ventriculoperitoneal shunt was re-performed on the contralateral side.

Although ventriculoperitoneal shunt is a common and simple method for the treatment of hydrocephalus, its complications are not rare. For the displacement of the peritoneal end of the shunt tube, we should further explore its predisposing factors, and aim to reduce its occurrence. In events of displacement, advanced technologies such as laparoscopy to reduce pain, trauma, and infection are recommended. They also accelerate patient recovery. Infection and inflammation should be assessed and treated prior to shunt replacement surgery. Ventricular-atrial shunt can be considered for repeated displacement and blockage of the peritoneal end.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nag DS S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Reddy GK, Bollam P, Shi R, Guthikonda B, Nanda A. Management of adult hydrocephalus with ventriculoperitoneal shunts: long-term single-institution experience. Neurosurgery. 2011;69:774-780; discussion 780-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Akyüz M, Uçar T, Göksu E. A thoracic complication of ventriculoperitoneal shunt: symptomatic hydrothorax from intrathoracic migration of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheter. Br J Neurosurg. 2004;18:171-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sridhar K, Sharma BS, Kak VK. Spontaneous extrusion of peritoneal catheter through intact abdominal wall. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1988;90:373-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kanojia R, Sinha SK, Rawat J, Wakhlu A, Kureel S, Tandon R. Unusual ventriculoperitoneal shunt extrusion: experience with 5 cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2008;44:49-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Borkar SA, Satyarthee GD, Khan RN, Sharma BS, Mahapatra AK. Spontaneous extrusion of migrated ventriculoperitoneal shunt catheter through chest wall: a case report. Turk Neurosurg. 2008;18:95-98. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kumar B, Sharma SB, Singh DK. Extrusion of ventriculo-peritoneal shunt catheter. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Allouh MZ, Al Barbarawi MM, Asfour HA, Said RS. Migration of the distal catheter of the ventriculoperitoneal shunt in hydrocephalus: A Comprehensive Analytical Review from an Anatomical Perspective. Clin Anat. 2017;30:821-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Taub E, Lavyne MH. Thoracic complications of ventriculoperitoneal shunts: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:181-183; discussion 183-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim JH, Jung YJ, Chang CH. Laparoscopic Treatment of Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Complication Caused by Distal Catheter Isolation Inside the Falciform Ligament. World Neurosurg. 2016;90:707.e1-707.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Basauri L, Selman JM, Lizana C. Peritoneal catheter insertion using laparoscopic guidance. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1993;19:109-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Esposito C, Porreca A, Gangemi M, Garipoli V, De Pasquale M. The use of laparoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of abdominal complications of ventriculo-peritoneal shunts in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 1998;13:352-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |