Published online Oct 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4521

Peer-review started: June 30, 2020

First decision: August 8, 2020

Revised: August 10, 2020

Accepted: August 26, 2020

Article in press: August 26, 2020

Published online: October 6, 2020

Processing time: 89 Days and 9.4 Hours

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects almost 3% of females of child-bearing age, who have a high risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Additionally, high renal burden as a result of pregnancy may lead to deterioration of renal function. An increasing number of women with CKD stages 3 to 5 have a strong desire to conceive, and both obstetricians and nephrologists are faced with enormous challenges in terms of their treatment and management.

The case of a 35-year-old pregnant woman with a 10-year history of mild mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis is described here. CKD progressed from stage 3 to stage 5 rapidly during pregnancy, and protective hemodialysis was started at 28 wk of gestation. Due to preeclampsia at 34 wk of gestation, cesarean section was performed and a healthy baby was delivered. Hemodialysis was discontinued at 4 wk postpartum. After 1 year of follow-up, her renal function was stable, and her baby exhibited good growth and development.

Protective hemodialysis during pregnancy can prolong gestational age and improve maternal and fetal outcomes in women with advanced CKD.

Core Tip: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects almost 3% of females of child-bearing age, who have a high risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. Only scarce cases of protective hemodialysis for CKD during pregnancy have been reported. We present herein the first case of successful pregnancy after protective hemodialysis for CKD in our institution. This case highlights the ultimate importance of protective hemodialysis. Protective hemodialysis during pregnancy can prolong gestational age and improve maternal and fetal outcomes in women with advanced CKD.

- Citation: Wang ML, He YD, Yang HX, Chen Q. Successful pregnancy after protective hemodialysis for chronic kidney disease: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(19): 4521-4526

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i19/4521.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4521

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global health issue that is characterized by abnormalities in the kidney structure or function that typically lasts for over 3 mo and has serious health implications[1,2]. CKD affects almost 3% of females of child-bearing age[3]. As a result of the decline in renal function, the incidence of complications during pregnancy increases significantly. Additionally, the likelihood of the progression of abnormalities in kidney function during pregnancy increases with each successive stage of CKD[4,5]. A previous study reported that nearly half of women with moderate and severe renal insufficiency (serum creatinine > 1.4 mg/dL) experience a decline in kidney function during pregnancy, and 23% of them progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) at 6 mo postpartum[6]. Another study in 2015 reported that two in ten patients with CKD stages 4 and 5 required dialysis[4].

Almost 98% of women with CKD stages 1 and 2 have a successful pregnancy; in this population, significant loss of renal function is unlikely, but possible[7-10]. The incidence of preterm labor in patients with CKD stage 3 is up to 75%, and in 50% of cases of preterm labor, delivery occurs before 34 wk of gestation[4]. In patients with CKD stages 4 and 5 (including patients who start dialysis after conception), the average gestational age at delivery is 33 wk and more than 50% of the neonates are small for age[4,11,12]. Over the years, the pregnancy outcomes of women with CKD (including advanced CKD) have been gradually improving in a way that is consistent with the advances in medical techniques[13]. In particular, an increasing number of women with CKD stages 3 to 5 have a strong desire to conceive. However, the number of reported cases of pregnancy in women with CKD stages 3 to 5 is still limited. As a result, both obstetricians and nephrologists are faced with enormous challenges in terms of providing individualized clinical strategies that are necessary.

In this case report, we describe a 35-year-old woman with CKD stage 3 that progressed to stage 5 during pregnancy. She received protective hemodialysis treatment, and she delivered a healthy baby at 34 wk of gestation. Hemodialysis was ceased at 4 wk postpartum and her renal function maintained stable during the 1-year follow-up.

A 35-year-old Chinese woman with CKD was admitted to our hospital at 28 wk of gestation due to a rapid decline of renal function.

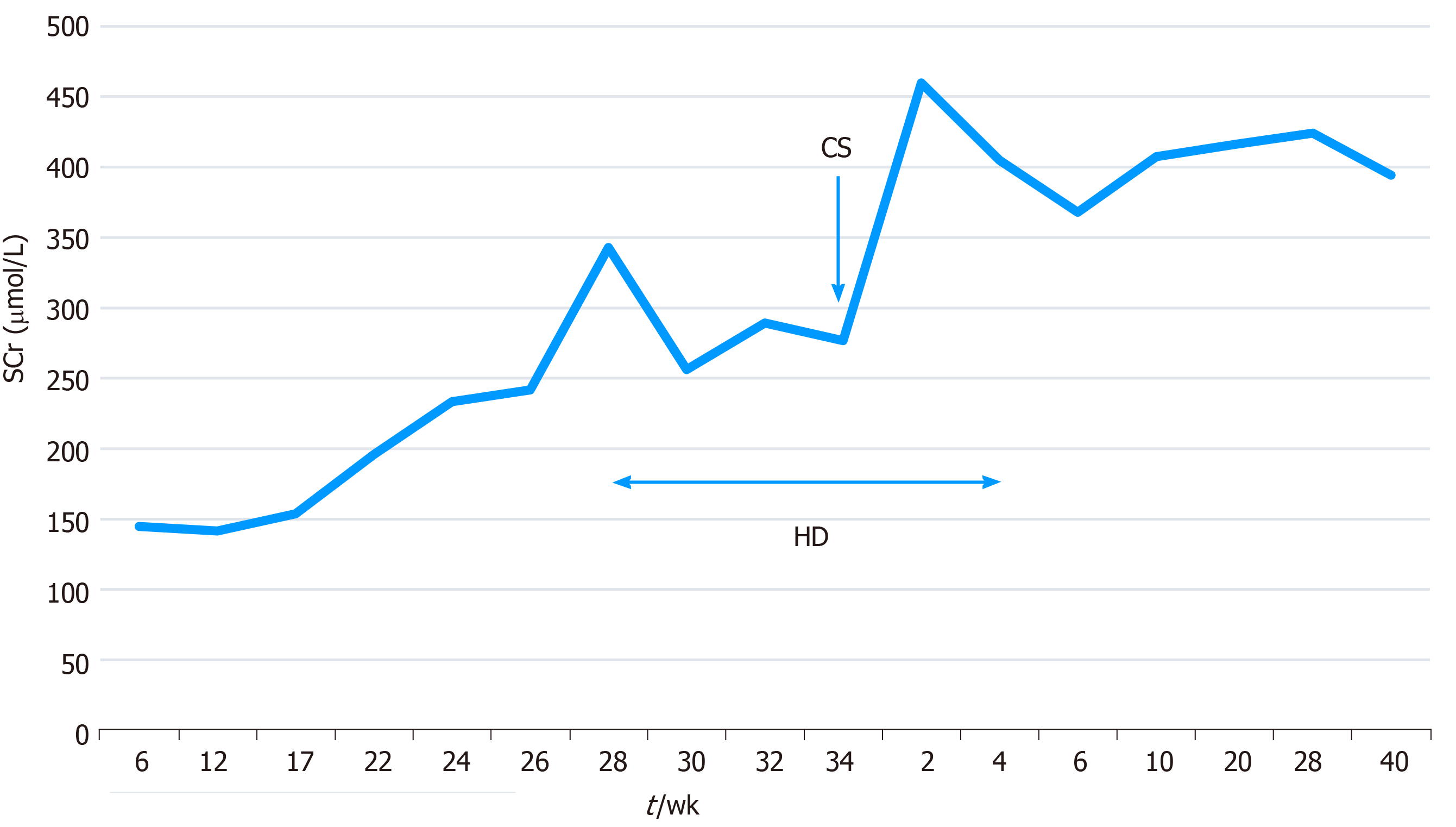

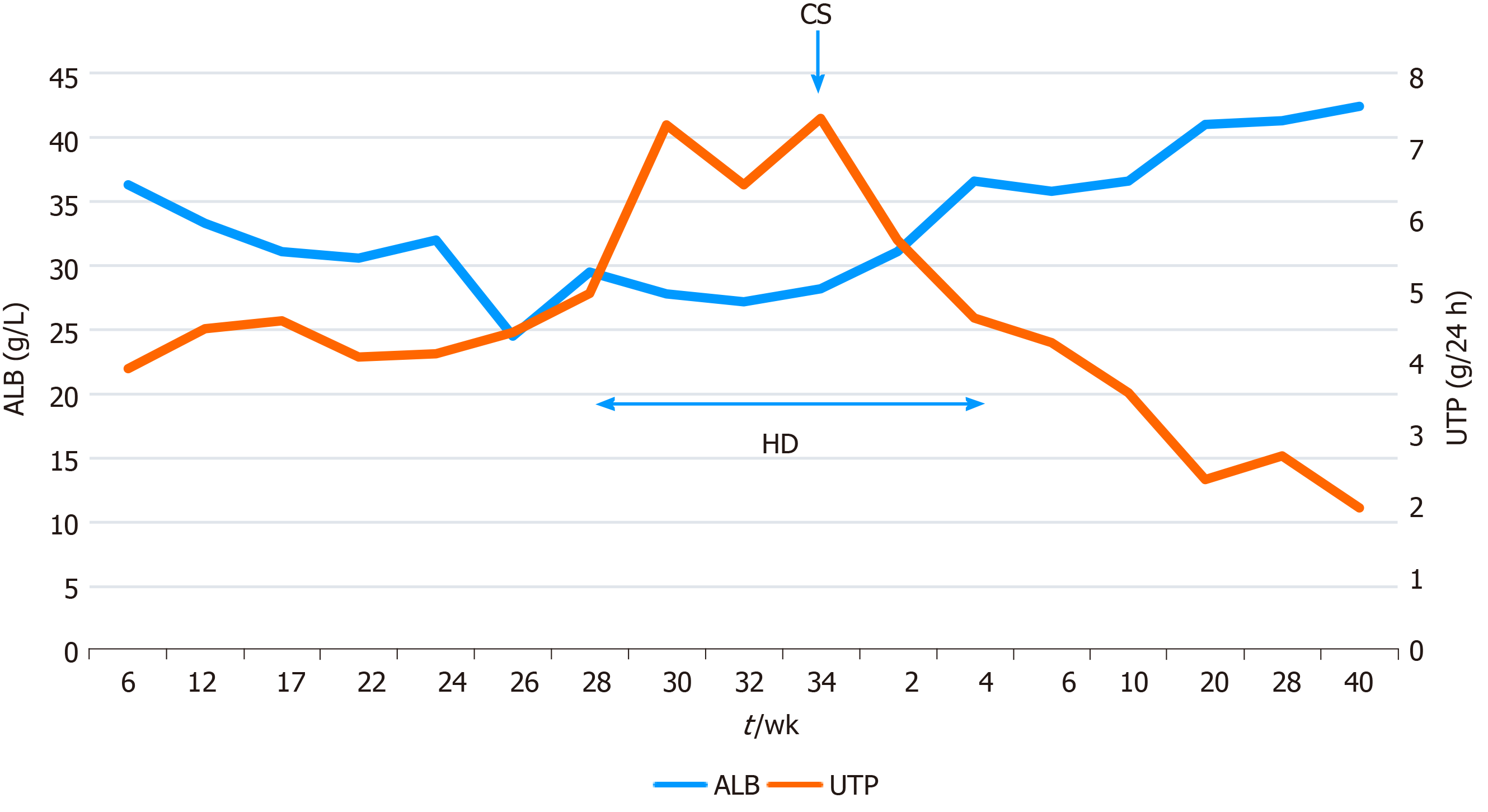

The patient presented at the clinic at 6 wk of gestation with a high serum creatinine level (145 μmol/L), severe proteinuria (3.91 g/24 h), and normal blood pressure (eGFR = 40.6 mL·min-1·1.73 m-2). She was in CKD stage 3. We stressed on the enormous risk of pregnancy to her and her family, but the patient insisted that she wanted to continue with the pregnancy. Based on the patient’s wish to continue with the pregnancy, she was prescribed prednisolone acetate (12.5 mg), tacrolimus (3.5 mg), hydroxychloroquine (300 mg), and folic acid (5 mg) daily. At 12 wk of gestation, she began to take aspirin (100 mg daily) to reduce the risk of preeclampsia. Antenatal care was provided every 2 wk during the second trimester and every week during the third trimester. The nutriture, blood pressure, and renal function of the patient, and fetal growth were closely monitored, as was blood flow in the uterine and umbilical arteries. The risk of chromosome abnormality in the fetus was found to be low through noninvasive prenatal testing, and the fetus developed at a normal rate without malformation. The patient’s renal function declined rapidly to CKD stage 5 during the second trimester. At 28 wk of gestation, her serum creatinine level increased to 343 μmol/L, and this was accompanied by severe proteinuria (4.95 g/24 h), a high urea level (15.1 mmol/L), and high blood pressure (eGFR = 14.2 mL·min-1·1.73 m-2).

The patient had a 10-year history of mild mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis. During her 10-year disease course, repeated withdrawal of medication in preparation for pregnancy had led to multiple recurrences of kidney disease and a decline in renal function.

One year ago, she visited our hospital for preconception counselling. At the time she visited the hospital, she was in CKD stage 2, and had increased serum creatinine levels (94 μmol/L) and proteinuria (2.92 g/24 h). She had been regularly taking prednisolone acetate (15 mg/d) and leflunomide (20 mg/d) for 6 mo. The adverse impact of pregnancy on renal function and the risk of obstetric complications were explained to her in detail. However, the patient expressed her strong desire to conceive, despite the risk of developing ESRD. Based on the guidance of the doctor, leflunomide was discontinued, and she started taking prednisolone acetate (15 mg), tacrolimus (3 mg), hydroxychloroquine (300 mg), and folic acid (400 µg) daily.

The patient’s heart beat was 96 bpm, temperature was 36.2 °C,respiration rate was 18 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 145/95 mmHg. Fetal heart rate was 155 bpm. There was no lower extremity edema.

Blood biochemical and urine analyses revealed a high serum creatinine level (343 μmol/L), high urea level (15.1 mmol/L), low albumin level (24.5 g/L), and severe proteinuria (4.95 g/24 h) (eGFR = 14.2 mL·min-1·1.73 m-2). The hemoglobin level was at 80 g/L.

The changes in the serum creatinine level during pregnancy and in the postpartum period are shown in Figure 1, and the corresponding serum albumin and urinary total protein values are shown in Figure 2.

Obstetric ultrasound revealed normal development of the fetus and normal blood flow in the uterine and umbilical arteries.

The diagnosis of the presented case at 28 wk of gestational was CKD stage 5 and gestational hypertension.

To prevent urea fetotoxicity, the patient was placed on protective intensive hemodialysis four times a week (3.5 h per session, without significant ultrafiltration), coupled with treatment for anemia and hypoalbuminemia. Additionally, labetalol hydrochloride (200 mg/d) was added to her regimen and her blood pressure returned to normal.

In order to accelerate fetal lung maturity, dexamethasone was administered at 28 wk and 32 wk of gestation. At 34 wk of gestation, her blood pressure increased to 170/110 mmHg and could not be controlled by medication; this could be a presentation of severe preeclampsia. Based on the patient’s obstetric indications, an elective caesarean section was carried out at 34 wk, and a baby weighing 2.08 kg was delivered.

The baby was in good condition and was discharged after 16 d of care in the neonatal intensive care unit. One week after delivery, that patient’s serum creatinine level was 450 μmol/L and she had proteinuria (6.32 g/24 h). However, her serum potassium and urine volume were normal and acidosis was not noted. Hemodialysis was continued with its frequency adjusted to once a week and was ceased at 4 wk postpartum. She continued to take the prescribed medication regularly. After 1 year of follow-up, her urinary total protein excretion gradually decreased to 2 g/24 h, but the serum creatinine concentration remained high at around 400 μmol/L. Her baby showed good growth and development.

In the present report, we describe the case of a female patient with CKD who wanted to conceive despite the associated risks. In such patients, it is necessary to assess the risk of adverse outcomes and the chances of a successful pregnancy before conception, and recommendations should be made according to the underlying renal disease, baseline renal function, the degree of proteinuria, and blood pressure[7].

Hypertension is a risk factor for renal function decline. Therefore, in women with CKD who want to conceive, it is recommended that the blood pressure be maintained at < 140/90 mmHg before conception and at < 135/85 mmHg during pregnancy[14]. Additionally, proteinuria (> 1 g/24 h) is an independent risk factor for preterm birth[4], and renal function deteriorates more rapidly in patients with proteinuria (urinary protein excretion, over 1 g/24 h) and low eGFR (less than 40 mL·min-1·1.73 m-2)[15]. In the present case, pregnancy was not recommended based on the low eGFR and severe proteinuria observed in early pregnancy. However, the patient insisted on conceiving despite the risk of developing to ESRD, as she was aware that her renal function would gradually decline in the future even if she did not give birth to a baby.

During pregnancy in women with CKD, urea fetotoxicity is likely to occur prior to maternal indications for dialysis[16]. Previous studies discovered a positive correlation between elevated urea levels and fetal mortality before dialysis[17,18]. In a study conducted in the 1960s, it was reported that no infant survived in five women with urea > 22.5 mmol/L[17]. Thus, for women with advanced CKD during pregnancy, the indication for dialysis depends on the level of urea toxicity in the fetus[16].

Hemodialysis should be implemented in pregnant women with a creatinine clearance rate less than 20 mL/min or a serum urea level over 17 mmol/L or 20 mmol/L[16,19]. The live birth rate is as high as 70% in all pregnant women with CKD requiring hemodialysis, and it is 91% in women with CKD who conceive before dialysis[11,20]. Therefore, in the present case, we conducted intensive protective hemodialysis to avoid urea fetotoxicity and fetal death.

According to nephrologists in the United States, hemodialysis is recommended for 4-4.5 h for 6 d/wk or an average of 23 ± 7 h/wk[20], whereas Italian experts suggest a minimum of 36 h/wk of hemodialysis during pregnancy[21]. The target predialysis urea level is less than 15 mmol/L following day break[19]. Due to the poor tolerance of the patient in this case, the frequency of hemodialysis was adjusted.

According to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, CKD is a high-risk factor for preeclampsia, and treatment with low-dose aspirin (75-150 mg/d) is recommended before 16 wk of gestation to reduce the risk of preeclampsia[14,22]. Hypertension is a frequent comorbidity of ESRD, but the possibility of preeclampsia must be considered if hypertension gets worse or damage to other maternal organs, fetal growth restriction, or abnormal flow in the uterine and umbilical arteries is observed[23]. In the present case, although without other maternal organ damage and fetal growth abnormal, the blood pressure could not be controlled with medication at 34 wk as a presentation of severe preeclampsia.

Determining the appropriate timing of birth is very important. It is recommended that the decision about the timing and mode of birth for women with CKD be determined based on the obstetric indications, considering deteriorating renal function and hypertension[14,23]. Protective hemodialysis can help to prolong gestational age, and in the absence of maternal and fetal complications, patients on hemodialysis can deliver after 37 wk of gestation[19,24]. In this case, caesarean section was performed due to the occurrence of severe preeclampsia at 34 wk of gestation.

The findings in the present case indicate that protective hemodialysis during pregnancy is beneficial to women with ESRD. Thus, in keeping with the reports of published studies, protective hemodialysis during pregnancy can prolong gestational age and improve the maternal and fetal outcomes in women with advanced CKD.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ekpenyong CE S-Editor: Wang DM L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1-S266. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Stevens PE, Levin A; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group Members. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:825-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1707] [Cited by in RCA: 2481] [Article Influence: 206.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Williams D, Davison J. Chronic kidney disease in pregnancy. BMJ. 2008;336:211-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Piccoli GB, Cabiddu G, Attini R, Vigotti FN, Maxia S, Lepori N, Tuveri M, Massidda M, Marchi C, Mura S, Coscia A, Biolcati M, Gaglioti P, Nichelatti M, Pibiri L, Chessa G, Pani A, Todros T. Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in Women with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2011-2022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Su X, Lv J, Liu Y, Wang J, Ma X, Shi S, Liu L, Zhang H. Pregnancy and Kidney Outcomes in Patients With IgA Nephropathy: A Cohort Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70:262-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jones DC, Hayslett JP. Outcome of pregnancy in women with moderate or severe renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:226-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Webster P, Lightstone L, McKay DB, Josephson MA. Pregnancy in chronic kidney disease and kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 2017;91:1047-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bar J, Ben-Rafael Z, Padoa A, Orvieto R, Boner G, Hod M. Prediction of pregnancy outcome in subgroups of women with renal disease. Clin Nephrol. 2000;53:437-444. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Jungers P, Houillier P, Forget D, Labrunie M, Skhiri H, Giatras I, Descamps-Latscha B. Influence of pregnancy on the course of primary chronic glomerulonephritis. Lancet. 1995;346:1122-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Alkhunaizi A, Melamed N, Hladunewich MA. Pregnancy in advanced chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24:252-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jesudason S, Grace BS, McDonald SP. Pregnancy outcomes according to dialysis commencing before or after conception in women with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:143-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Piccoli GB, Fassio F, Attini R, Parisi S, Biolcati M, Ferraresi M, Pagano A, Daidola G, Deagostini MC, Gaglioti P, Todros T. Pregnancy in CKD: whom should we follow and why? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27 Suppl 3:iii111-iii118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hall M. Pregnancy in Women With CKD: A Success Story. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68:633-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wiles K, Chappell L, Clark K, Elman L, Hall M, Lightstone L, Mohamed G, Mukherjee D, Nelson-Piercy C, Webster P, Whybrow R, Bramham K. Clinical practice guideline on pregnancy and renal disease. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Imbasciati E, Gregorini G, Cabiddu G, Gammaro L, Ambroso G, Del Giudice A, Ravani P. Pregnancy in CKD stages 3 to 5: fetal and maternal outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:753-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wiles K, de Oliveira L. Dialysis in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2019;57:33-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mackay EV. Pregnancy and Renal Disease A Ten-Year Survey. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1963;3:21-34. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fairley KF, Kincaid-Smith P. Renal disease in pregnancy. Postgrad Med J. 1968;44:45-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hladunewich M, Schatell D. Intensive dialysis and pregnancy. Hemodial Int. 2016;20:339-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sachdeva M, Barta V, Thakkar J, Sakhiya V, Miller I. Pregnancy outcomes in women on hemodialysis: a national survey. Clin Kidney J. 2017;10:276-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cabiddu G, Castellino S, Gernone G, Santoro D, Giacchino F, Credendino O, Daidone G, Gregorini G, Moroni G, Attini R, Minelli F, Manisco G, Todros T, Piccoli GB; Kidney and Pregnancy Study Group of Italian Society of Nephrology. Best practices on pregnancy on dialysis: the Italian Study Group on Kidney and Pregnancy. J Nephrol. 2015;28:279-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | LeFevre ML; U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:819-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hui D, Hladunewich MA. Chronic Kidney Disease and Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1182-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tangren J, Nadel M, Hladunewich MA. Pregnancy and End-Stage Renal Disease. Blood Purif. 2018;45:194-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |