Published online Oct 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4475

Peer-review started: June 19, 2020

First decision: July 24, 2020

Revised: July 30, 2020

Accepted: September 2, 2020

Article in press: September 2, 2020

Published online: October 6, 2020

Processing time: 100 Days and 4.9 Hours

Genitourinary (GU) schistosomiasis is a chronic infection caused by a parasitic trematode, with Schistosoma haematobium (S. haematobium) being the prevalent species. The disease has a variable prevalence around the world, with a greater burden on, but not limited to Africa, South America, Asia, and the Middle East.

We report the case of a 30-year-old man who presented with symptoms of bladder stones. During endoscopic cystolithalopaxy, we did not detect any stones in the bladder. Upon careful scanning of the urinary bladder trigone, sandy patches were detected. We performed endoscopic resection, which revealed a closed diverticulum with bladder stones. The diverticular wall was sent for histopathology and revealed features of chronic granulomatous inflammation with numerous embedded Schistosoma eggs, with some of the eggs having lateral spines. The patient was treated with praziquantel, and his symptoms completely resolved.

GU schistosomiasis is primarily caused by S. haematobium. However, Schistosoma mansoni mediated GU schistosomiasis is unusual, making this a quite interesting case.

Core Tip: Genitourinary (GU) schistosomiasis is a chronic infection caused by the parasitic trematode, with Schistosoma haematobium being the prevalent species. We report a case of a 30-year-old male who presented with GU schistosomiasis due to Schistosoma manosoni which is a rare incidence.

- Citation: Alkhamees MA. Bladder stones in a closed diverticulum caused by Schistosoma mansoni: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(19): 4475-4480

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i19/4475.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4475

Genitourinary (GU) schistosomiasis is a chronic infection induced by the parasitic trematode of the genus Schistosoma. It has been well described as a cause of urinary disease predominantly in Egyptian papyri[1]. Schistosoma haematobium (S. haematobium) is the primary schistosome species causing GU schistosomiasis. It is considered the third most devastating tropical disease in the world, with variable prevalence around the world[2]. Africa, South America, Asia, and the Middle East are the most frequently affected regions. It has been estimated that over 230 million people are infected with Schistosoma spp. Worldwide[3]. The World Health Organization has reported 200000 deaths per year due to schistosomiasis in sub-Saharan Africa[4].

The range of diseases caused by schistosomes is highly variable, depending on the organ system involved[3]. Adult male and female worms live, mate, and produce eggs within the veins of their human host. The eggs that are shed into the external environment infect suitable host snails. Asexual replication occurs within the snails to produce infectious larvae called cercariae. It is the cercariae that penetrate the human skin and enter the body. S. haematobium is the most predominant species of GU infection and specifically resides in the perivascular venules[3]. Its high association with bladder cancer makes it a serious parasite[5,6]. Urinary schistosomiasis inflammation can be categorized into cellular (Type IV hypersensitivity) or humoral (mainly Type III) immune response, with the humoral response carrying the risk of cancer[1]. The early phase of the infection is usually inflammatory, along with classical features such as inflammatory granulomata involving the bladder and lower ureters. At this phase, patients usually present with increased episodes of hematuria and dysuria. Microscopic examination of the urine at this stage can diagnose the infection[1]. The later phase is dominated by parenchymal-mesenchymal transformation, where the granulomata are modulated, fibrosed, or calcified[1]. Herein, we report the case of a 30-year-old man who had GU schistosomiasis caused by parasitic eggs with a lateral spine (i.e., S. mansoni), which is rarely reported in the literature.

A 30-year-old Yemini man presented to the emergency department in our hospital complaining of dysuria with associated lower abdominal and penile pain for months. The patient was consequently referred to our urology department for further evaluation.

The patient’s symptoms started 6 mo prior to presentation. He is not known to have any medical condition.

He denied any history of urolithiasis, hematuria, or other lower urinary tract symptoms.

The physical examination results were unremarkable.

Urinalysis was inconclusive and was not suggestive of urinary tract infection (UTI). Laboratory investigations revealed a normal creatinine concentration of 80 μmol/L.

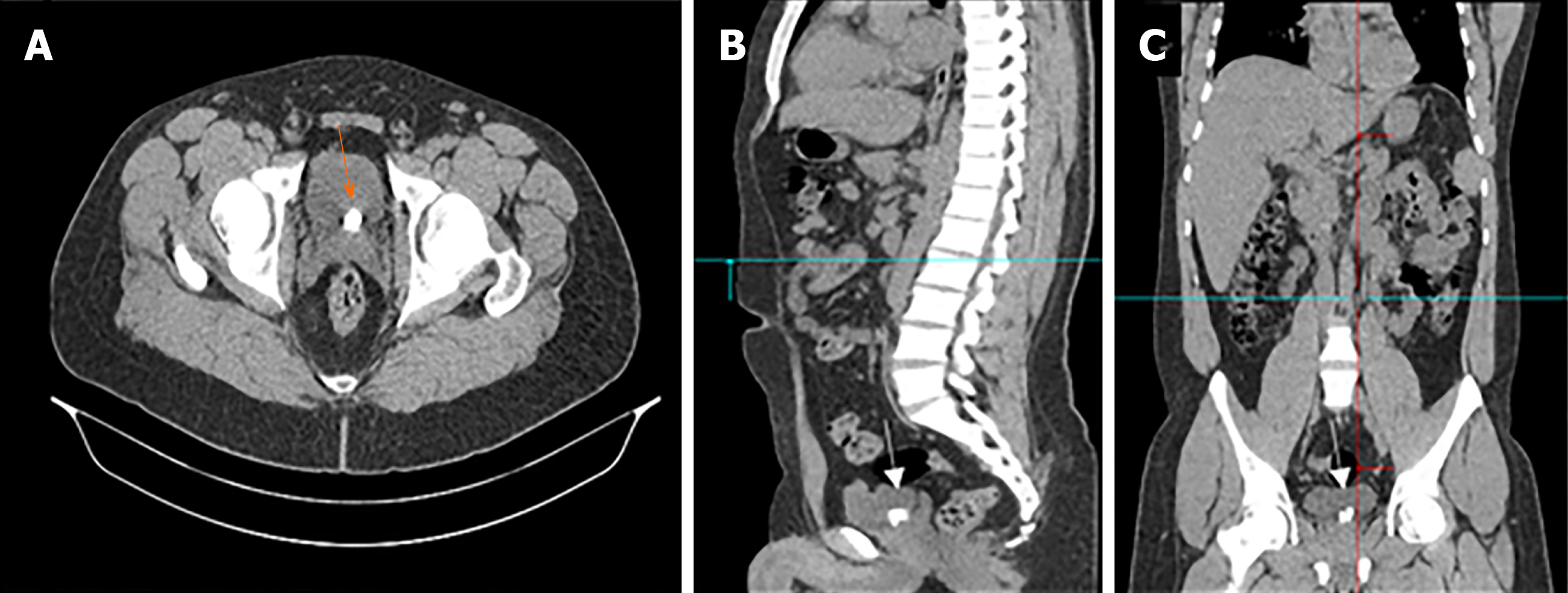

An initial renal and bladder ultrasound detected multiple bladder stones. Accordingly, we performed a computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast. The CT scan revealed multiple bladder stones with a burden of 1.5 cm and was otherwise normal (Figure 1).

Following consultation with the patient, we decided to perform an endoscopic cystolithalopaxy. During the procedure, we observed with a cystoscope that the urethra was normal. Although the bladder neck was mildly elevated and hyperemic, no stones or diverticula were detected. Upon inspection of the trigone, we observed a central inter-ureteric bulge with sandy patches over the urothelium. Further careful scanning revealed no evidence of a diverticular neck. Therefore, we decided to perform a minor resection of the inter-ureteric bulge. Using a monopolar resectoscope, a brief resection was performed, and multiple stones were seen within a closed diverticulum. Consequently, complete deroofing was performed. All stones were fragmented and extracted cystoscopically. The diverticular wall was then sent for histopathological examination. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged the following day with no active issues.

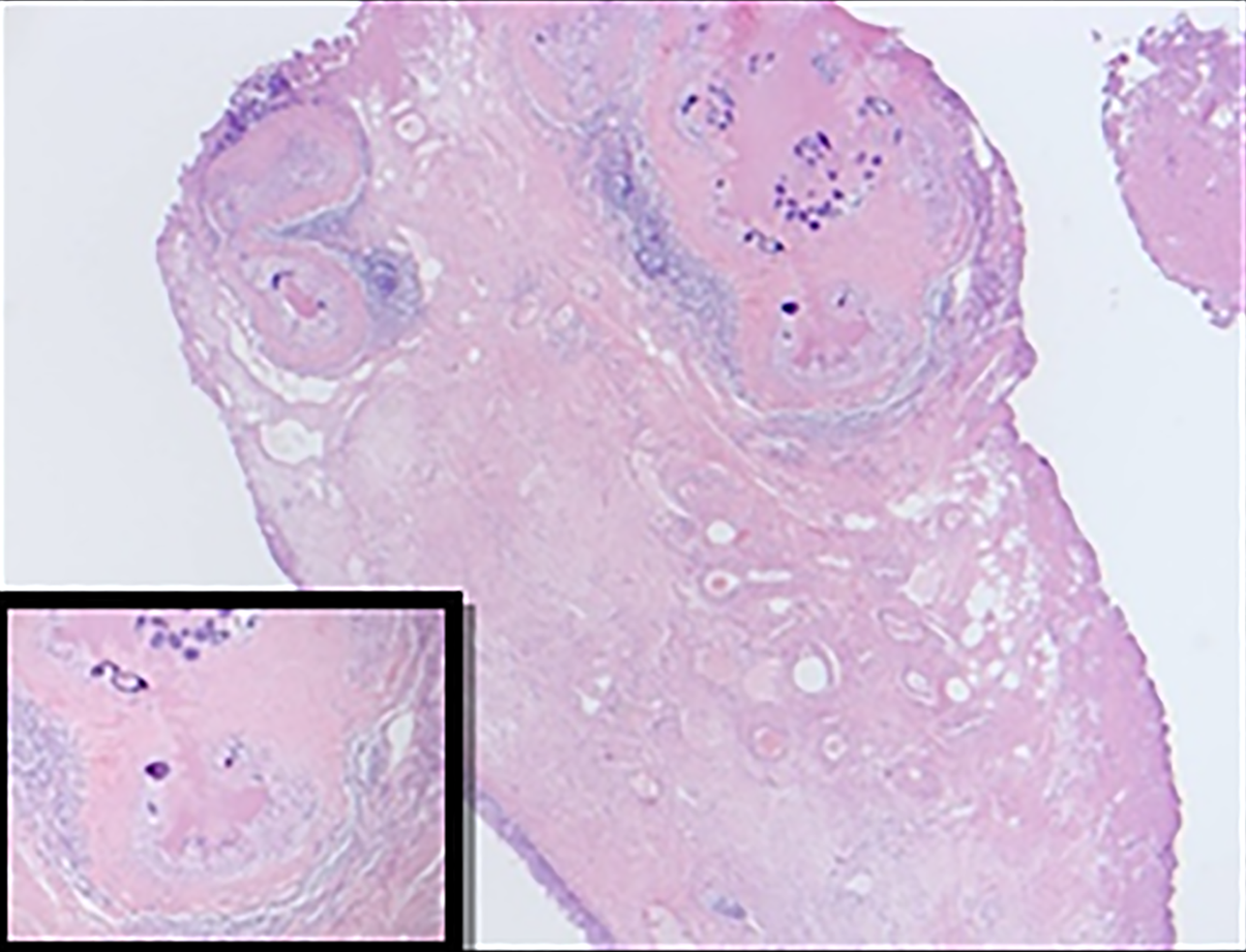

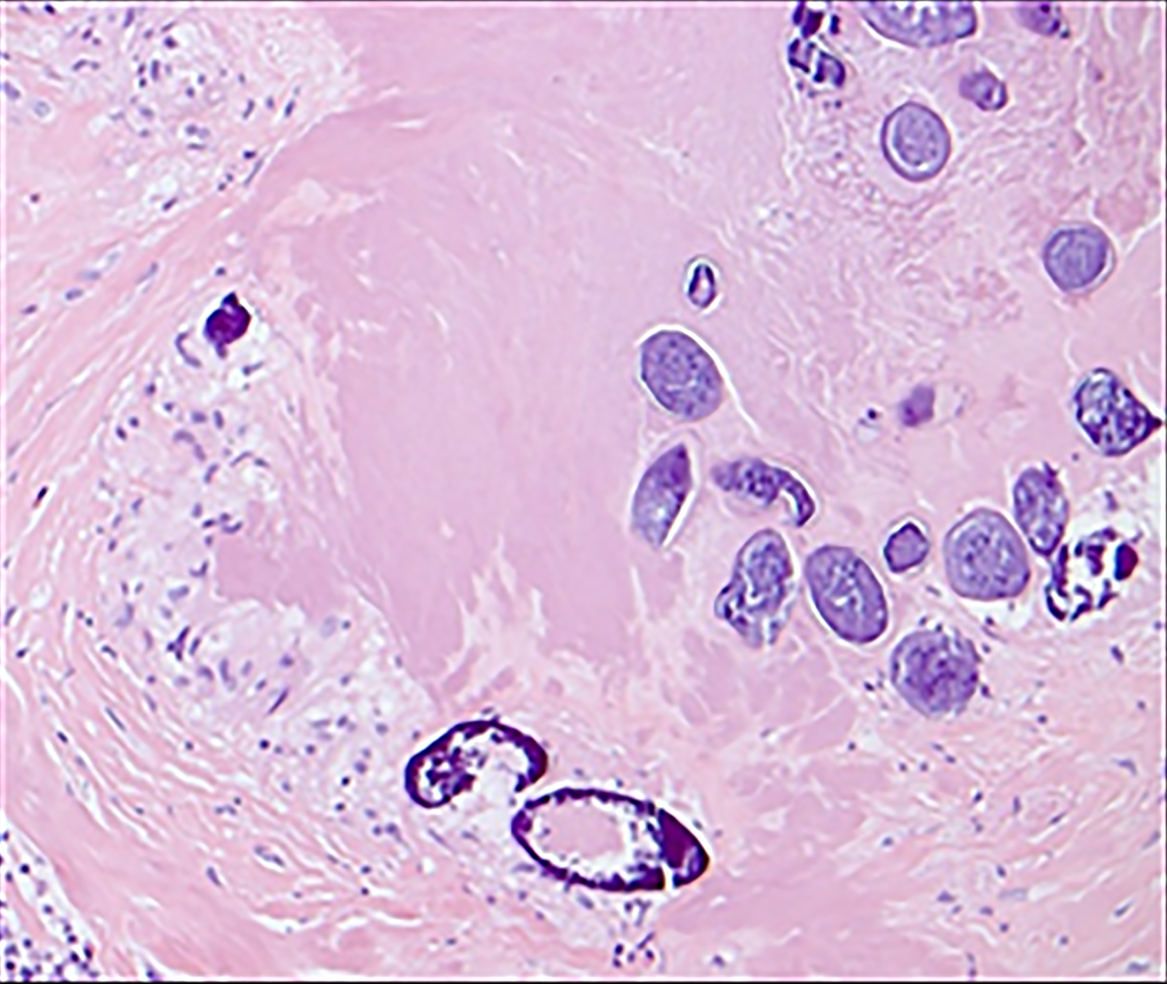

Histopathological examination revealed features of chronic granulomatous inflammation with scattered multinucleate reactive giant cells around numerous embedded Schistosoma eggs. Some of the eggs had lateral spines with sporadic degeneration and calcification. No definite atypia or malignancy was detected (Figures 2 and 3).

The patient received praziquantel (40 mg/kg) in two divided doses for one day.

At the follow-up visit two weeks later, the patient reported complete relief from his symptoms. A urine sample collected for microscopic examination revealed no evidence of Schistosoma eggs. The patient reported no recurrence of symptoms at the two-month follow-up visit. Even though we recommended a PCR test, the patient did not follow up.

Schistosomiasis infection is a serious tropical disease with variable prevalence; the majority of cases are reported in developing countries. The type of schistosomiasis is highly dependent on the affected organs. S. haematobium usually resides and infects the GU tract, while S. mansoni, S. japonicum, and S. mekongi reside and infect the liver and gastrointestinal tract. It is important to include schistosomiasis in the differential diagnosis when dealing with patients with no urological features but who are from a schistosomiasis endemic region. Common features of GU schistosomiasis include, but are not limited to, hematuria and dysuria[7]. Our patient had urological symptoms and lived in an endemic area, consistent with the diagnosis of GU schistosomiasis. On physical examination, generalized lymphadenopathy is common, and it is paramount to examine the skin for possible maculopapular rash, which indicates penetration of the cercaria larva. Moreover, approximately one-third of patients will have splenomegaly[7]. However, we did not observe any such indications upon physical examination of our patient. It should be taken into consideration that schistosomiasis may also mimic metastatic malignancy. A case report which occurred in the United Kingdom describes a patient who was suspected to have bladder cancer with pulmonary metastasis. However, detailed history revealed a visit to an endemic country, and urinary cytology revealed S. haematobium. The patient was treated with praziquantel, which resolved lesions in the bladder, lungs, and lymph nodes[2].

It is important to mention that as schistosomes cannot excrete waste products due to the lack of an anus, they disgorge directly into the bloodstream. Some of these regurgitated wastes are essential for blood-based and urine-based diagnostic purposes[3]. A systematic review of 90 articles concluded that microhematuria determined by microscopy efficiently identified a large proportion of infections and non-infections[8]. In addition to urine testing, a complete blood count indicates eosinophilia in over 80% of acutely infected patients[7]. In recent years, sophisticated PCR methods such as high-resolution melting curve assays have emerged to diagnose schistosomiasis with high sensitivity and specificity[9].

The imaging modalities in GU schistosomiasis depend on the location. In the case of the bladder, patchy calcifications producing the picture of “cystitis cystica” may be observed. Another characteristic radiological sign is calcification of the seminal vesicles[1]. A study that reviewed 153 Egyptian men with GU schistosomiasis concluded that the most common finding by urography is obstructive uropathy associated with significant bladder calcification, ureteral stenosis, and ureterolithiasis[10]. The presence of “sandy patches” is another common and classical observation by cystoscopy. These are areas of roughened bladder mucosa surrounding the egg deposits that were evident in our patient[7].

A definitive diagnosis of schistosomiasis requires histopathology, which reveals the characteristic S. haematobium eggs with their terminal spines and granulomas. The current understanding is that S. haematobium is the cause of GU schistosomiasis, while other Schistosoma species cause intestinal schistosomiasis[1,9,11,12]. However, our patient showed the presence of eggs with a lateral spine with GU schistosomiasis, which could indicate the possibility of an infection with another Schistosoma species. A case report that occurred in Turkey describes an old man from a S. mansoni non-endemic area who developed transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder secondary to S. mansoni infection. Although the association between S. Haematobium and bladder cancer is well-established, the association between S. mansoni and bladder cancer is uncertain due to the lack of sufficient evidence in the literature[13]. Moreover, a study in Cameroon, which included 1118 children, revealed that 162 (14.5%) children had S. mansoni eggs in the urine, and 33 (3%) children had S. haematobium eggs in the feces[14].

Nephropathy and renal failure are also complications associated with GU schistosomiasis. Nephrotic syndrome is caused by immune complex deposition in the glomerular capillaries and basement membrane in response to S. haematobium[15]. Immunofluorescent studies of these immune complexes have detected IgM, IgG, IgE, and occasionally IgA deposits[16]. A systematic review of urological complications of GU schistosomiasis surmised that there was no difference in urinary stone incidence between patients with or without GU schistosomiasis[15]. However, the authors of another study hypothesized that infective stone formation is higher among GU schistosomiasis patients[1].

Although the first report relied on systematic evidence, the second assumption is more consistent with our patient who developed multiple bladder stones. Administration of praziquantel (40 mg/kg) for such cases is the most standard evidence-based regimen[17]. Despite the patient reporting complete symptom resolution, we could not confirm absolute elimination of the parasite by PCR as he did not maintain follow-up visits.

The author would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Majmaah University for supporting this work under Project Number No. R-1441-149.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Saudi Urological Association, No. 41531.

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: Saudi Arabia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ju SQ S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Barsoum RS. Urinary schistosomiasis: review. J Adv Res. 2013;4:453-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hosny K, Luk A. Urinary schistosomiasis presented as bladder malignancy with pulmonary metastases: a case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2018;100:e145-e146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Colley DG, Bustinduy AL, Secor WE, King CH. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2014;383:2253-2264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1693] [Cited by in RCA: 1721] [Article Influence: 156.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | WHO Expert Committee. Prevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2002;912:i-vi, 1-57, back cover. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mostafa MH, Sheweita SA, O'Connor PJ. Relationship between schistosomiasis and bladder cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:97-111. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Rambau PF, Chalya PL, Jackson K. Schistosomiasis and urinary bladder cancer in North Western Tanzania: a retrospective review of 185 patients. Infect Agent Cancer. 2013;8:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gray DJ, Ross AG, Li YS, McManus DP. Diagnosis and management of schistosomiasis. BMJ. 2011;342:d2651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ochodo EA, Gopalakrishna G, Spek B, Reitsma JB, van Lieshout L, Polman K, Lamberton P, Bossuyt PM, Leeflang MM. Circulating antigen tests and urine reagent strips for diagnosis of active schistosomiasis in endemic areas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;CD009579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sady H, Al-Mekhlafi HM, Ngui R, Atroosh WM, Al-Delaimy AK, Nasr NA, Dawaki S, Abdulsalam AM, Ithoi I, Lim YA, Chua KH, Surin J. Detection of Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma haematobium by Real-Time PCR with High Resolution Melting Analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:16085-16103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Young SW, Khalid KH, Farid Z, Mahmoud AH. Urinary-tract lesions of Schistosoma haematobium with detailed radiographic consideration of the ureter. Radiology. 1974;111:81-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee Y, Song HB, Jung BK, Choe G, Choi MH. Case Report of Urinary Schistosomiasis in a Returned Traveler in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2020;58:51-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sotillo J, Pearson MS, Becker L, Mekonnen GG, Amoah AS, van Dam G, Corstjens PLAM, Murray J, Mduluza T, Mutapi F, Loukas A. In-depth proteomic characterization of Schistosoma haematobium: Towards the development of new tools for elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kiremit MC, Cakir A, Arslan F, Ormeci T, Erkurt B, Albayrak S. The bladder carcinoma secondary to schistosoma mansoni infection: A case report with review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;13:76-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cunin P, Tchuem Tchuenté LA, Poste B, Djibrilla K, Martin PM. Interactions between Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma mansoni in humans in north Cameroon. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:1110-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Khalaf I, Shokeir A, Shalaby M. Urologic complications of genitourinary schistosomiasis. World J Urol. 2012;30:31-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Andrade ZA, Rocha H. Schistosomal glomerulopathy. Kidney Int. 1979;16:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kramer CV, Zhang F, Sinclair D, Olliaro PL. Drugs for treating urinary schistosomiasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD000053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |