Published online Oct 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4311

Peer-review started: April 4, 2020

First decision: June 18, 2020

Revised: July 1, 2020

Accepted: August 29, 2020

Article in press: August 29, 2020

Published online: October 6, 2020

Processing time: 176 Days and 9.1 Hours

Transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) is a good choice for resection of rectal neoplasms. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is also widely used in the treatment of benign rectal tumors such as rectal polyps and rectal adenomas. However, no studies have compared the outcome of TAMIS and EMR.

To compare the short-term outcomes after TAMIS and EMR for rectal carcinoid and benign tumors (including rectal polyps and adenomas).

From January 2014 to January 2019, 44 patients who received TAMIS and 53 patients who received EMR at The Fifth People’s Hospital of Shanghai were selected. Primary outcomes (surgical-related) were operating time, blood loss, length of postoperative hospital stay, rate of resection margin involvement and lesion fragmentation rate. The secondary outcomes were complications such as hemorrhage, urinary retention, postoperative infection and reoperation.

No significant differences were observed in terms of blood loss (12.48 ± 8.00 mL for TAMIS vs 11.45 ± 7.82 mL for EMR, P = 0.527) and length of postoperative hospital stay (3.50 ± 1.87 d for TAMIS vs 2.72 ± 1.98 d for EMR, P = 0.065) between the two groups. Operating time was significantly shorter for EMR compared with TAMIS (21.19 ± 9.49 min vs 49.95 ± 15.28 min, P = 0.001). The lesion fragmentation rate in the EMR group was 22.6% (12/53) and was significantly higher than that (0%, 0/44) in the TAMIS group (P = 0.001). TAMIS was associated with a higher urinary retention rate (13.6%, 6/44 vs 1.9%, 1/53 P = 0.026) and lower hemorrhage rate (0%, 0/44 vs 18.9%, 10/53 P = 0.002). A significantly higher reoperation rate was observed in the EMR group (9.4%, 5/53 vs 0%, 0/44 P = 0.036).

Compared with EMR, TAMIS can remove lesions more completely with effective hemostasis and lower postoperative hemorrhage and reoperation rates. TAMIS is a better choice for the treatment of rectal carcinoids.

Core Tip: This is a retrospective study aiming to compare the short-term outcomes of transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for rectal neoplasms. The surgical-related outcomes and postoperative complication rates in 44 patients who received TAMIS and 53 patients who received EMR were compared. The results showed that the EMR group was associated with longer operating time and higher lesion fragmentation rate, while the TAMIS group had lower postoperative hemorrhage and reoperation rates.

- Citation: Shen JM, Zhao JY, Ye T, Gong LF, Wang HP, Chen WJ, Cai YK. Transanal minimally invasive surgery vs endoscopic mucosal resection for rectal benign tumors and rectal carcinoids: A retrospective analysis. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(19): 4311-4319

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i19/4311.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i19.4311

According to the 2018 global cancer statistics report, the incidence of colorectal cancer was ranked fourth after lung cancer, breast cancer and prostate cancer. In China, the morbidity and mortality of colorectal cancer rank second and fifth, respectively[1]. Rectal adenoma is the main precancerous lesion of rectal cancer. Early and timely treatment of rectal adenoma and early rectal cancer can effectively reduce the morbidity and mortality of rectal cancer[2]. Therefore, importance should be attached to the treatment of rectal adenoma and early rectal cancer.

Transanal excision can only treat lesions within 6 cm of the anal verge[3]. However, transanal endoscopic microsurgery can treat early rectal cancer and benign rectal tumors ranging from 6 cm to 18 cm from the anal verge. Only a few surgery centers in China have transanal endoscopic microsurgery devices due to the cost and long learning curve involved[4-6]. First proposed by Atallah et al[7] in 2009, transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) can solve the above problems. TAMIS combines single-incision laparoscopic surgery with more flexible transanal platforms, the learning curve is shorter and the purchase of expensive equipment can be avoided. In addition, TAMIS guarantees a good therapeutic effect in rectal polyps, rectal adenomas, early rectal cancer and other rectal mucosal lesions in the upper and middle rectum[8,9].

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is commonly used in the treatment of benign rectal tumors such as rectal polyps and rectal adenomas[10]. However, no studies have compared the outcome of TAMIS and EMR. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the data on TAMIS and EMR performed at The Fifth People’s Hospital of Shanghai, Fudan University. This study compared the short-term outcomes after TAMIS and EMR for rectal neoplasms. We hope that this study will help surgeons in the choice of treatment for benign rectal tumors and rectal carcinoids.

A total of 97 patients with rectal carcinoid and benign rectal diseases who received TAMIS and EMR in our hospital from January 2014 to January 2019 were selected. The patients were divided into the TAMIS group and EMR group according to the different surgical methods.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: Age between 30 and 80 years; single rectal carcinoid and benign rectal diseases including polyps and adenomas at a distance of 5-15 cm from the anal verge; diameter of the lesion ≤ 3 cm; asymptomatic or only hematochezia present; no previous anorectal surgery; and no severe circulatory or respiratory diseases.

The exclusion criteria were: The presence of other benign anorectal diseases such as anal fistula, hemorrhoids, perianal abscess, etc.; the presence of hemorrhagic disease, diabetes or other diseases that may affect the outcome; women who were pregnant or lactating.

There were no significant differences in age, gender, body mass index and pathological type between the two groups (P < 0.05). Pathology was based on the pathological results after surgery, benign lesions included rectal polyps and rectal adenoma (Table 1).

| Characteristics | TAMIS, n = 44 | EMR, n = 53 | P value |

| Age, yr | 64.25 ± 10.85 | 60.70 ± 10.38 | 0.104 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.383 | ||

| Male | 21 (47.7) | 30 (56.6) | |

| Female | 23 (52.3) | 23 (44.4) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.88 ± 2.46 | 22.43 ± 1.98 | 0.322 |

| Tumor size, cm | 1.47 ± 0.96 | 1.14 ± 0.53 | 0.033 |

| Benign | 1.46 ± 1.02 | 1.06 ± 0.50 | 0.024 |

| Carcinoid | 1.52 ± 0.72 | 1.64 ± 0.45 | 0.702 |

| Distance from the anal verge, cm | 7.39 ± 1.86 | 8.83 ± 2.95 | 0.006 |

| Final pathology, n (%)1 | 0.220 | ||

| Benign | 34 (77.3) | 46 (86.8) | |

| Carcinoid | 10 (22.7) | 7 (13.2) |

Preoperative management: All patients were given a low-slag, liquid diet (prepared by Department of Nutrition, The Fifth People’s Hospital of Shanghai, Fudan University) and polyethylene glycol electrolyte powder enema 1 d before surgery. The patients were fasted for 8 h and no liquids were permitted 6 h prior to treatment.

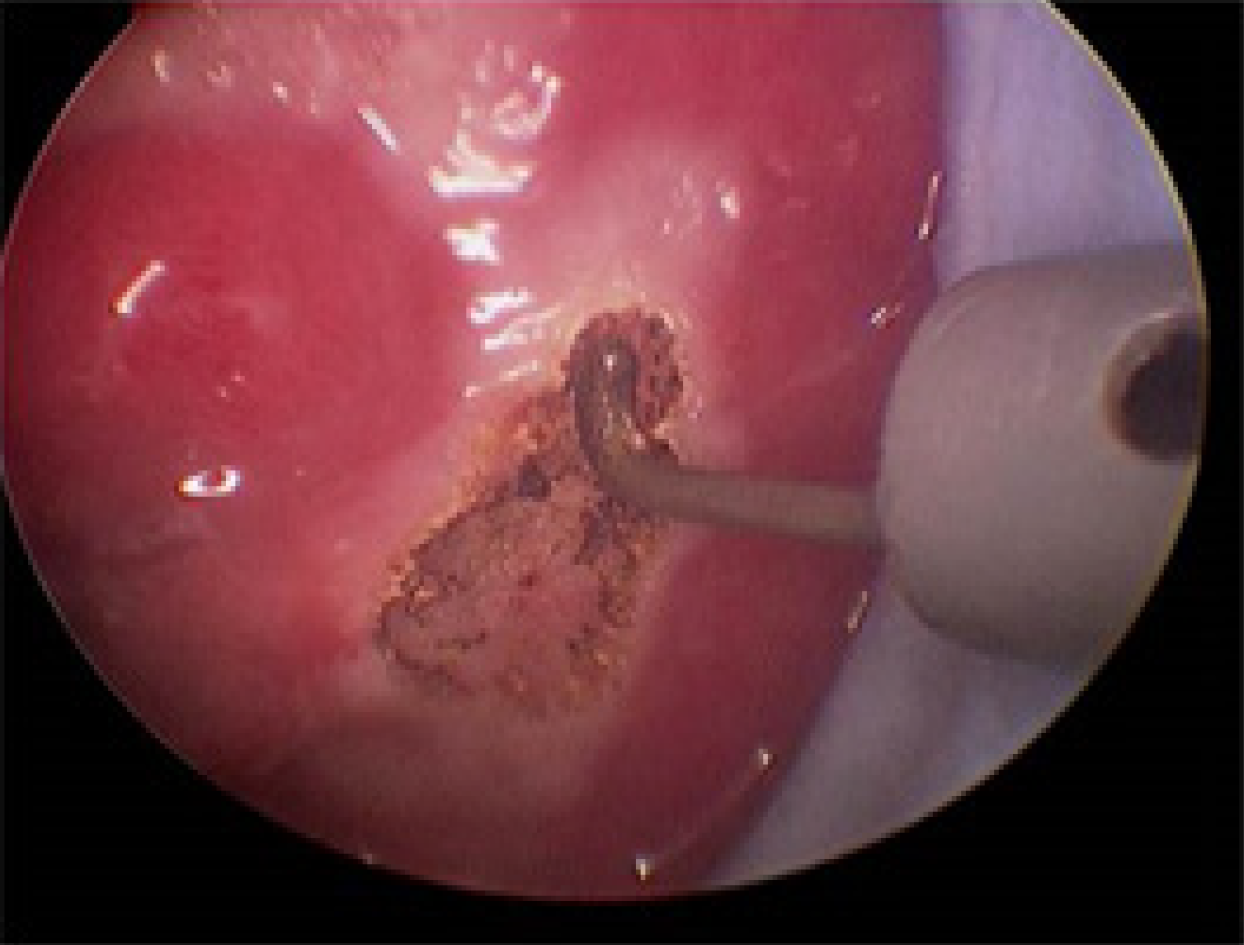

TAMIS: The patients were given general anesthesia and placed in the lithotomy position (Figure 1). GelPOINT (Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, United States) was fixed to the anus, and CO2 pressure was maintained at 15 mmHg and 12 L/min (Figure 2). An airbag catheter was placed in the distal part of the surgical field, 10-15 mL of air was injected into the airbag and the airbag was expanded to seal the proximal rectum (in some cases, this step was replaced by placing gauze 10 cm from the proximal end of the lesion). An electric hook was used to cut a distance of 0.5 cm from the tumor (Figure 3), the mucosa was incised and the submucosa or muscle layer was gradually incised, depending on the depth of the lesion, until the resection was complete. Closure of the rectal defect was performed with a free barbed suture.

EMR: Preoperative preparation was the same as for the TAMIS group. First, a normal saline solution containing epinephrine (0.01 mg/mL) was injected into the submucosa around the lesion to lift it away from the muscularis propria and thereby reduce the potential risk of perforation. A snare was then passed through the channel and opened around the lesion. The adequately lifted tumor was then snared and resected. Only when en-bloc resection was not feasible, fragmentary resection was allowed. Titanium clips were used for hemostasis.

The primary outcomes in this study were surgical-related and included operating time, blood loss, length of postoperative hospital stay, rate of resection margin involvement and lesion fragmentation rate. Secondary outcomes were complications such as hemorrhage (hemorrhage was defined as self-limited hematochezia and melena that did not require endoscopic hemostasis after surgery), urinary retention, postoperative infection and reoperation. Reoperation included intestinal perforation repair, endoscopic clip hemostasis and radical resection of rectal carcinoid.

Categorical data are expressed as number and percentage. Continuous data are described as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between the groups were analyzed using the Chi-square test for categorical data and the one sample t-test for continuous data. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All data analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21.0 statistical software.

There were no significant differences in age, gender, body mass index and final pathology between the two groups. The mean distance from the anal verge in the TAMIS group was 7.39 ± 1.86 cm and was significantly shorter than that (8.83 ± 2.95 cm) in the EMR group (P = 0.006). The mean tumor size in the TAMIS group was 1.47 ± 0.96 cm, which was larger than that in the EMR group at 1.14 ± 0.53 cm (P = 0.033). The carcinoid size in the two groups was similar (1.52 ± 0.72, range 0.60-3.00 cm for TAMIS vs 1.64 ± 0.45, range 1.00-2.20 cm for EMR, P = 0.702). Only one carcinoid patient in the TAMIS group had a lesion smaller than 1 cm.

The mean operating time was significantly shorter for TAMIS than for EMR: 21.19 ± 9.49 min vs 49.95 ± 15.28 min, respectively (P < 0.001). No significant differences in blood loss (P = 0.527), length of stay (P = 0.065) and resection margin involvement (P = 0.109) were observed. The lesion fragmentation rate in the EMR group was 22.6% (12/53) and was significantly higher than 0% (0/44) in the TAMIS group (P = 0.001) (Table 2).

| Characteristics | TAMIS, n = 44 | EMR, n = 53 | P value |

| Operative time, min | 49.95 ± 15.28 | 21.19 ± 9.49 | < 0.001 |

| Blood loss, mL | 12.48 ± 8.00 | 11.45 ± 7.82 | 0.527 |

| Length of stay, d | 3.50 ± 1.87 | 2.72 ± 1.98 | 0.065 |

| Resection margins, n (%) | 0.109 | ||

| Negative | 44 (100) | 50 (94.3) | |

| Positive | 0 (0) | 3 (5.7) | |

| Fragmentation, n (%) | 0 (0) | 12 (22.6) | 0.001 |

The rate of hemorrhage in the EMR group was 18.9% (10/53) and was significantly higher than 0% (0/44) in the TAMIS group (P = 0.026). The urinary retention rate was 13.6% (6/44) and 1.9% (1/53) in the TAMIS and EMR groups, respectively, and was significantly higher in the TAMIS group compared with the EMR group (P = 0.026). No significant difference was observed in the postoperative infection rate between the two groups. Five patients (9.4%) in the EMR group required reoperations, and none of the patients in the TAMIS group required reoperations (P = 0.036) (Table 3).

| Complication | TAMIS, n = 44 | EMR, n = 53 | P value |

| Any, n (%) | 7 (15.9) | 17 (32.1) | |

| Hemorrhage, n (%) | 0 (0) | 10 (18.9) | 0.002 |

| Urinary retention, n (%) | 6 (13.6) | 1 (1.9) | 0.026 |

| Postoperative infection, n (%) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (1.9) | 0.894 |

| Reoperation, n (%)1 | 0 (0) | 5 (9.4) | 0.036 |

| Resection margin involvement, n | 0 | 3 | |

| Postoperative Bleeding, n2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Perforation, n | 0 | 1 |

TAMIS is a type of minimally invasive surgery in which the single-hole laparoscopic channel is inserted into the anal canal and laparoscopic instruments are used to perform local resection of rectal lesions[11]. Since Atallah et al[7] proposed TAMIS in 2009[7], TAMIS was quickly promoted worldwide with an excellent curative effect, reduced surgical trauma, fast postoperative recovery and low cost. TAMIS is mainly used in the treatment of middle and upper rectal polyps, adenomas and early rectal cancer 6-18 cm away from the anal verge[12,13]. Currently, researchers have applied TAMIS in the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors, low rectal anastomotic fistulas, rectal urethral fistulas and the removal of high rectal foreign bodies[14-16]. In addition, robot-assisted TAMIS[17,18], transanal minimally invasive surgery for total mesorectal excision technology[19-21], TAMIS-laparoscopy combined technology[22] and endoscopic-assisted TAMIS have also been rapidly developed[23]. However, there are no available data comparing the outcomes of local excision of early rectal cancers and benign tumors using TAMIS and EMR. This study aimed to compare the short-term efficacy of TAMIS and EMR.

The mean distance from the anal verge in the TAMIS group was 7.39 ± 1.86 cm and was significantly shorter than 8.83 ± 2.95 cm in the EMR group (P = 0.006). The mean tumor size in the TAMIS group was 1.47 ± 0.96 cm, which was larger than that in the EMR group at 1.14 ± 0.53 cm (P = 0.033). These differences may have been caused by the tendency of doctors to choose certain surgical methods. For tumors with a larger diameter, surgeons are more likely to perform TAMIS, and for tumors further from the anus, they are more likely to perform EMR. In the EMR group, the mean tumor size of carcinoids was larger than that of rectal benign tumors (1.64 ± 0.45 cm vs 1.06 ± 0.50 cm, P = 0.005), and three of seven patients with carcinoid underwent radical resection due to resection margin involvement. This result suggests that the lesion size should be taken into consideration in the selection of surgical methods.

No significant differences were observed in blood loss (P = 0.527) and length of postoperative stay (P = 0.065). The mean operating time in the TAMIS group was significantly longer than that in the EMR group (49.95 ± 15.28 min vs 21.19 ± 9.49 min, P < 0.001). In TAMIS, the establishment of pnuemorectum and placement of a single-hole laparoscope were required, which prolonged the operation time.

The rate of tumor-positive margin in the EMR group was 3.7% (3/53) and was slightly higher than 0% (0/44) in the TAMIS group (P = 0.109). The lesion fragmentation rate in the EMR group was 22.6% (12/53) and was significantly higher than 0% (0/44) in the TAMIS group (P = 0.001). These differences suggested that compared with EMR, TAMIS can completely resect rectal tumors without cutting the lesion itself, which is more in line with the principles of noncutting and monolithic resection in tumor surgery. It is also more suitable for the treatment of benign rectal diseases and rectal carcinoids.

The urinary retention rate in the TAMIS group was 13.6% (6/44) and was significantly higher than 1.9% (1/53) in the EMR group (P = 0.026). This may have been related to the difference in anesthesia between the two groups or due to stimulation of pelvic floor nerves during surgery. A significantly higher rate of hemorrhage was observed in the EMR group (0%, 0/44 vs 18.9%, 10/53 P = 0.002). In the EMR group, high-frequency electrocoagulation and titanium clip clamping were used for hemostasis and wound closure. When the surgical incision is large, the effect of electrocoagulation hemostasis cannot be guaranteed, and the titanium clip has the risk of detachment. It has been reported that a lesion diameter greater than 2 cm increases the risk of hemorrhage after EMR[24]. In the TAMIS group, the wound was closed with barbed absorbable sutures on the basis of ultrasonic coagulation, which effectively reduced the risk of postoperative bleeding.

In the EMR group, reoperations were performed in five cases, including one case of perforation, one case of postoperative bleeding and three cases of rectal carcinoid that underwent radical resection due to resection margin involvement. The reoperation rate in the EMR group was 9.4% (5/53) and was significantly higher than 0% (0/44) in the TAMIS group (P = 0.036). This result suggested that for patients with rectal carcinoids, TAMIS is a better choice because it can remove the lesions more completely. An airbag catheter was placed in the distal part of the surgical field and was inflated (in some cases, gauze was placed into the rectum about 10 cm from the proximal end of the lesion instead) to seal the proximal rectum and avoid interference due to intestinal secretions and fecal water in the surgical field of view. Pnuemorectum can also help to obtain a clearer surgical field of view and better expose the lesions to ensure complete and full-thickness resection of rectal tumors.

The database used in this study is based on real world data. As a retrospective study, avoiding major bias was a focus of the study. The surgeon’s choice of surgical method is affected by the severity of the disease, the size of the lesion and the distance of the lesion from the anus, which will directly affect the reliability of the results in this study. We eliminated this bias by matching and ensuring that the baseline patient characteristics in the two groups were similar. We selected patients who were asymptomatic or only had hematochezia, the diameter of the lesion was ≤ 3 cm and the distance of the lesion from the anal margin was 5-15 cm.

In summary, EMR is simpler and can be performed by a single person with a shorter operating time. In addition, EMR is less invasive and more suitable for the treatment of rectal polyps and adenomas with a longer distance from the anus. TAMIS surgery requires more surgical instruments, a larger surgical field, deeper and more thorough tumor resection, more effective hemostasis and results in lower hemorrhage and reoperation rates. It is a better choice for the treatment of rectal carcinoids.

Transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) is a good choice for resection of benign lesions and carcinoids in the rectum. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is also widely used in the treatment of benign rectal tumors such as rectal polyps and rectal adenomas. However, no studies have compared the outcome of TAMIS and EMR.

We hope that this study will help surgeons in the choice of treatment for benign rectal lesions and rectal carcinoids.

We compared the short-term outcomes after TAMIS and EMR for rectal carcinoid and benign tumors (including rectal polyps and adenomas).

The short-term outcomes after TAMIS and EMR for rectal carcinoids and benign tumors (including rectal polyps and adenomas) was compared.

TAMIS was associated with a higher urinary retention rate (13.6%, 6/44 vs 1.9%, 1/53 P = 0.026) and lower hemorrhage rate (0%, 0/44 vs 18.9%, 10/53 P = 0.002). A significantly higher reoperation rate was observed in the EMR group (9.4%, 5/53 vs 0%, 0/44 P = 0.036).

Compared with EMR, TAMIS can remove rectal tumors more completely with effective hemostasis and lower postoperative hemorrhage and reoperation rates. TAMIS is a better choice for the treatment of rectal carcinoids and benign rectal tumors with a large diameter.

TAMIS surgery requires more surgical instruments, a larger surgical field, deeper and more thorough tumor resection, more effective hemostasis and results in lower hemorrhage and reoperation rates. It is a better choice for the treatment of rectal carcinoids.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abd El-Razek A, Khayyat YM, Koch T S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53206] [Cited by in RCA: 55701] [Article Influence: 7957.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (132)] |

| 2. | Wolf AMD, Fontham ETH, Church TR, Flowers CR, Guerra CE, LaMonte SJ, Etzioni R, McKenna MT, Oeffinger KC, Shih YT, Walter LC, Andrews KS, Brawley OW, Brooks D, Fedewa SA, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Siegel RL, Wender RC, Smith RA. Colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults: 2018 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:250-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 945] [Cited by in RCA: 1304] [Article Influence: 186.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | García-Flórez LJ, Otero-Díez JL, Encinas-Muñiz AI, Sánchez-Domínguez L. Indications and Outcomes from 32 Consecutive Patients for the Treatment of Rectal Lesions by Transanal Minimally Invasive Surgery. Surg Innov. 2017;24:336-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Maslekar S, Pillinger SH, Sharma A, Taylor A, Monson JR. Cost analysis of transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal tumours. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:229-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Barendse RM, Dijkgraaf MG, Rolf UR, Bijnen AB, Consten EC, Hoff C, Dekker E, Fockens P, Bemelman WA, de Graaf EJ. Colorectal surgeons' learning curve of transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3591-3602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Maya A, Vorenberg A, Oviedo M, da Silva G, Wexner SD, Sands D. Learning curve for transanal endoscopic microsurgery: a single-center experience. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1407-1412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Atallah S, Albert M, Larach S. Transanal minimally invasive surgery: a giant leap forward. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2200-2205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Haugvik SP, Groven S, Bondi J, Vågan T, Brynhildsvoll SO, Olsen OC. A critical appraisal of transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) in the treatment of rectal adenoma: a 4-year experience with 51 cases. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:855-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Clermonts SHEM, van Loon YT, Schiphorst AHW, Wasowicz DK, Zimmerman DDE. Transanal minimally invasive surgery for rectal polyps and selected malignant tumors: caution concerning intermediate-term functional results. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:1677-1685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim J, Kim JH, Lee JY, Chun J, Im JP, Kim JS. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection for rectal neuroendocrine tumor. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Atallah S, Albert M, Monson JR. Critical concepts and important anatomic landmarks encountered during transanal total mesorectal excision (taTME): toward the mastery of a new operation for rectal cancer surgery. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20:483-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Maglio R, Muzi GM, Massimo MM, Masoni L. Transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS): new treatment for early rectal cancer and large rectal polyps—experience of an Italian center. Am Surg. 2015;81:273-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Albert MR, Atallah SB, deBeche-Adams TC, Izfar S, Larach SW. Transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) for local excision of benign neoplasms and early-stage rectal cancer: efficacy and outcomes in the first 50 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:301-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cawich SO, Mohammed F, Spence R, Albert M, Naraynsingh V. Colonic Foreign Body Retrieval Using a Modified TAMIS Technique with Standard Instruments and Trocars. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2015;2015:815616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Atallah S, Albert M, Debeche-Adams T, Larach S. Transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS): applications beyond local excision. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:239-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wolthuis AM, Cini C, Penninckx F, D'Hoore A. Transanal single port access to facilitate distal rectal mobilization in laparoscopic rectal sleeve resection with hand-sewn coloanal anastomosis. Tech Coloproctol. 2012;16:161-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hompes R, Rauh SM, Ris F, Tuynman JB, Mortensen NJ. Robotic transanal minimally invasive surgery for local excision of rectal neoplasms. Br J Surg. 2014;101:578-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liu S, Suzuki T, Murray BW, Parry L, Johnson CS, Horgan S, Ramamoorthy S, Eisenstein S. Robotic transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) with the newest robotic surgical platform: a multi-institutional North American experience. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:543-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Atallah S, Albert M, DeBeche-Adams T, Nassif G, Polavarapu H, Larach S. Transanal minimally invasive surgery for total mesorectal excision (TAMIS-TME): a stepwise description of the surgical technique with video demonstration. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:321-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Atallah S, Martin-Perez B, Albert M, deBeche-Adams T, Nassif G, Hunter L, Larach S. Transanal minimally invasive surgery for total mesorectal excision (TAMIS-TME): results and experience with the first 20 patients undergoing curative-intent rectal cancer surgery at a single institution. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:473-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wexner SD, Berho M. Transanal TAMIS total mesorectal excision (TME)--a work in progress. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:423-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lee SG, Russ AJ, Casillas MA. Laparoscopic transanal minimally invasive surgery (L-TAMIS) vs robotic TAMIS (R-TAMIS): short-term outcomes and costs of a comparative study. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:1981-1987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | McLemore EC, Coker A, Jacobsen G, Talamini MA, Horgan S. eTAMIS: endoscopic visualization for transanal minimally invasive surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1842-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | van Hattem WA, Bourke MJ. Prevention is better than cure: the challenges of prophylactic therapy for post-EMR bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:823-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |