Published online Sep 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i18.4228

Peer-review started: June 22, 2020

First decision: July 24, 2020

Revised: July 28, 2020

Accepted: August 20, 2020

Article in press: August 20, 2020

Published online: September 26, 2020

Processing time: 91 Days and 22.9 Hours

A pelvic floor hernia is defined as a pelvic floor defect through which the intraabdominal viscera may protrude. It is an infrequent complication following abdominoperineal surgeries. This type of hernia requires surgical repair by conventional or reconstructive techniques. The main treatments could be transabdominal, transperineal or a combination.

In this article, we present the case of a recurrent perineal incisional hernia, postresection of the left side of the pelvis, testis and lower limbs resulting from a mine disaster 18 years ago. Combined laparoscopic surgery with a perineal approach was performed. The pelvic floor defect was repaired by a biological mesh and one pedicle skin flap. No signs of recurrence were indicated during the 2 years of follow-up.

The combination of laparoscopic surgery with a perineal approach was effective. The use of the biological mesh and pedicle skin flap to restructure the pelvic floor was effective.

Core Tip: The combination of laparoscopic surgery with a perineal approach for complicated pelvic floor hernias could be a better way to improve the safety and effectiveness of surgery. The application of the biological mesh and flaps is safe and effective with a good long-term outcome. Hernioplasty of the pelvic floor hernia via an associated pathway is technically feasible, is associated with rapid recovery and minimal complications and has a good long-term outcome. The use of a biological mesh and flaps to repair the defect likely improves results, especially for patients with a larger pelvic floor hernia or the possibility of severe adhesion and potential infection.

- Citation: Chen K, Lan YZ, Li J, Xiang YY, Zeng DZ. Mine disaster survivor’s pelvic floor hernia treated with laparoscopic surgery and a perineal approach: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(18): 4228-4233

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i18/4228.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i18.4228

A pelvic floor hernia is the protrusion of an intra-abdominal structure into the perineal area that could be primitive or secondary to trauma or abdominoperineal resection[1,2]. Based on the anatomical site and the hernia contents, pelvic floor hernias can be divided into ischiatic hernias, obturator hernias, peritoneoceles and perineal hernias. Weakness of the endopelvic fascia and musculature leads to herniation of the intraabdominal and pelvic organs, such as the small bowel, colon and bladder. It is five times more common in women, presumably because of a broad pelvis and childbirth[3,4]. The majority of cases are secondary to traumatic injury to the perineum or secondary to major pelvis operations, such as abdominoperineal resection and pelvic exenteration. Clinical diagnosis is difficult, and imaging modalities, such as ultrasound and computed tomography of the pelvis, will confirm the diagnosis[5].

Surgery-related pelvic floor hernia was first described in 1939[6]. Few reports have focused on this disease, and no large-scale studies have been reported. In recent decades, however, the number of reported cases of pelvic floor hernia has gradually increased worldwide[7]. Surgical repair was previously described via transabdominal, transperineal and combined approaches. Primary closure, mesh placement (e.g., composite mesh or biological mesh) and reconstruction using myocutaneous flaps have been documented. The therapy of pelvic floor hernia is very controversial[8]. Methods for both approach and technique of closure vary in the existing literature. This may be caused by the complex anatomy of the pelvic floor. Identification and especially mobilization of muscular and fascial components can be very difficult. Therefore, an individual strategy must be developed. The case report of a patient with a secondary complicated pelvic floor hernia details clinical aspects, emphasizing the method of surgical procedure. The division of adhesions, separation of the bladder, careful reinforcing with pedicle skin flaps and adequate positioning of the biological mesh are important keys to surgical success.

A 48-year-old Chinese male patient came to our attention complaining of a 15 year history of a gradually enlarging perineal bulge with skin erosion after the first hernioplasty. Intestinal fistula was diagnosed, which was relieved after dressing change. The patient also presented with slight persistent local discomfort but no abdominal pain and no urinary or defective symptoms.

The skin of the perineal bulge ulcerated, suppurated and bled repeatedly, which resulted in the exposure of part of the mesh. He suffered from these discomforts instead of visiting the hospital for financial reasons. Finally, he presented to our hospital with his wife 2 years ago.

The patient survived a mine disaster without the left side of the pelvis, the testis and the lower limbs 18 years ago. Unfortunately, he developed a pelvic floor hernia 3 years later. He underwent hernioplasty with a composite mesh via a transperineal approach. However, the intra-abdominal structure protruded into the perineal area again before long. The pelvic floor hernia recurred unexpectedly and lasted 15 years since then.

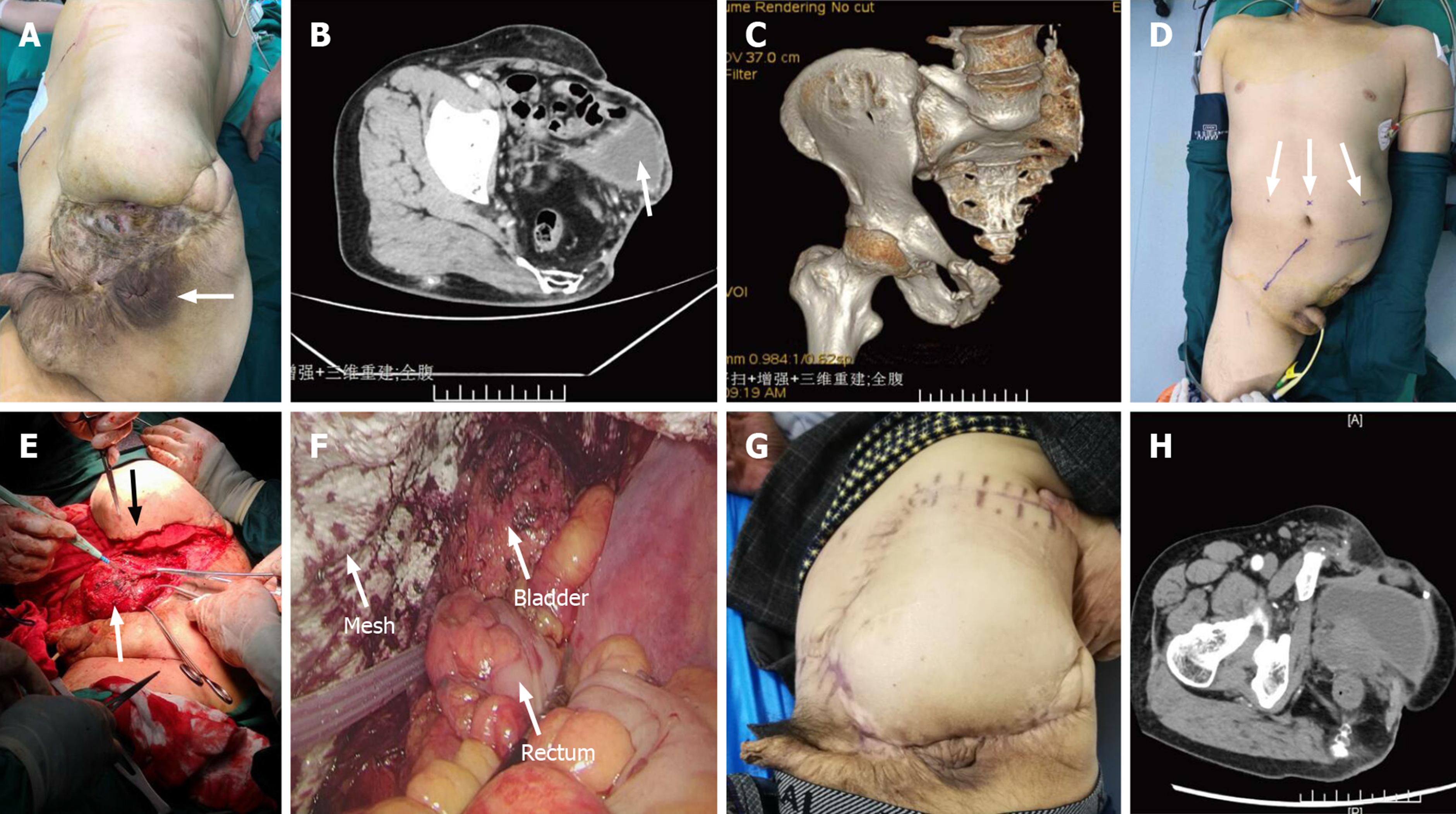

No abnormality was found in his vital signs. Physical examination showed no obvious cardiovascular or respiratory abnormalities. The general exam was negative. A local exam revealed bulge and festering skin (Figure 1A).

Electrocardiogram was unremarkable, and laboratory examination results, including blood, urine, stool, liver and kidney function and coagulation tests, were within normal ranges.

Based on the examination results, together with the patient's history and symptoms, a pelvic floor hernia was diagnosed.

We built a multidisciplinary treatment team, which included gastrointestinal surgery, urological surgery, plastic surgery, the anesthesia department and the intensive care unit, to solve the problem of treatment difficulties, such as recurrence, severe adhesion, intestinal fistula, bladder, operation pathway and selection and fixation point of the mesh with or without a flap. Finally, the operation procedure was divided into three stages.

The patient was placed in the horizontal position, and an umbilical port and two additional operating ports were placed in the upper abdomen (Figure 1D). The laparoscopic view revealed intra-abdominal adhesions between the small intestine and the bottom of the pelvis. We dissected the moderate adhesion easily. Intra-abdominal contamination unexpectedly occurred because all layers of the small intestine wall were injured during dissection of the tough, intractable adhesion. The damaged portion of the intestine was repaired with full-thickness interrupted sutures.

The patient was placed in the right lateral position, and we added a perineal approach to dissociate the bladder from the pelvic floor. At the same time, we excised the infected composite mesh and tissue of the pelvic floor. The epidermal tissue corresponding to the skin of the bladder was removed so we could put it back into the enterocoelia totally. Then, we designed one piece of pedicled skin flap. Flap transfer was performed to wrap the bladder in the abdominal cavity and reconstruct the left pelvic floor, which closed the pelvic floor defect simultaneously (Figure 1E).

The patient positioning and port placement were the same as in stage 1. We dissected the moderate adhesion of the bladder and the left ureter to reserve the placement of the mesh. We measured defect size and fixed a biological mesh (a flat-shaped 20 cm × 20 cm biological mesh) over the defect with a hernia titanium stapler and nonabsorbable suture (Figure 1F).

The recovery after the operation was uneventful without complications such as bleeding and infection. No signs of recurrence were signaled during the 2 year follow-up (Figure 1G and H).

A pelvic floor hernia is classified as primary or secondary according to its etiology[2], and, in general, most cases are secondary. Laparoscopic abdominoperineal excision of the rectum, perioperative radiation, perineal wound infection, extensive levator muscle resection and weakened pelvic floor muscles are considered risk factors for the pelvic floor[1,9]. Some patients with pelvic floor hernia have various symptoms, including perineal bulging with discomfort, intestinal obstruction or skin erosion[1]; however, some patients are asymptomatic and incidentally diagnosed at the time of their regular postoperative check-ups. A pelvic floor hernia has a unique physical appearance, and the definitive diagnosis is usually confirmed by abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography[8].

The optimal strategy for pelvic floor hernia treatment remains controversial, although various strategies have been proposed. Methods for both approach and technique of closure vary in the existing literature[4,10-17]. Therefore, an individual strategy must be developed.

Laparoscopy is probably the most useful means of identifying a hernial defect and has the advantage of allowing immediate treatment[18]. The laparoscopic approach provides an excellent magnified view of the surgical field, is less invasive for patients and is associated with a shorter hospital stay[19]. However, the laparoscopic approach requires advanced techniques and proficiency in laparoscopic surgery. Especially during dissection of the pelvic floor adhesions, the laparoscopic approach is limited by the range of motion of the laparoscopic instrument at the pelvic floor. The addition of the perineal approach is a good solution to overcome this disadvantage. The perineal approach provides surgeons with an excellent view of the pelvic floor. From the perineal side, however, the surgical field is limited with respect to recognizing important anatomical structures and visualizing the abdominal cavity. Thus, the laparoscopic approach is a good solution to overcome these disadvantages of the perineal approach. Since the early 2010s, perineal and laparoscopic approaches have been increasingly indicated[17].

A recent report documented that mesh placement using nonabsorbable mesh, composite mesh or biological mesh was performed in approximately 75% of patients, and flap reconstruction with autogenous tissue was used in approximately 25% of patients[17]. Primary closure of pelvic floor defects has decreased[17,20]. Flap reconstruction has rapidly become more widely used, and a lower associated recurrence rate has been documented[17,21]. Flap reconstruction is advantageous in terms of infection prevention because no foreign bodies are used. Therefore, flap reconstruction of the pelvic floor could be a surgical option for patients with a risk of local infection and may become more widely used as a pelvic floor hernia treatment technique in the near future[21].

Biological mesh is considered a promising technique for improving wound healing and complication rates comparable to other techniques[22]. The biological mesh acts not only as a structural support for hernia repair but also as a scaffold allowing the ingrowth of native fibroblasts, which in turn lay down fibrous tissue and promote tissue remodeling[23].

In our opinion, the combination of laparoscopic surgery with a perineal approach for complicated pelvic floor hernias could be a better way to improve the safety and effectiveness of surgery. The application of the biological mesh and flaps is safe and effective with a good long-term outcome.

Hernioplasty of the pelvic floor hernia via an associated pathway is technically feasible, is associated with rapid recovery and minimal complications and has a good long-term outcome. The use of a biological mesh and flaps to repair the defect likely improves results, especially for patients with a larger pelvic floor hernia or a possibility of severe adhesion and potential infection. Importantly, surgical intervention should be performed as early as possible to avoid more invasive approaches and unpleasant complications.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nakanishi Y S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Goedhart-de Haan AM, Langenhoff BS, Petersen D, Verheijen PM. Laparoscopic repair of perineal hernia after abdominoperineal excision. Hernia. 2016;20:741-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Berendzen J, Copas P. Recurrent perineal hernia repair: a novel approach. Hernia. 2013;17:141-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jermy KV, Stanton SL, Nager CW, Kumar D. A leiomyomatous perineal hernia? Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:507-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cali RL, Pitsch RM, Blatchford GJ, Thorson A, Christensen MA. Rare pelvic floor hernias. Report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:604-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Palumbo VD, Di Trapani B, Molinelli B, Tomasini S, Bruno A, Tomasello G. The saxophonist's hernia: a rare case report of anterior primary perineal hernia in a young male patient. Clin Ter. 2017;168:e133-e135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yeomans FC. Levator hernia, perineal and pudendal. Am J Surg. 1939;43:695-697. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mjoli M, Sloothaak DA, Buskens CJ, Bemelman WA, Tanis PJ. Perineal hernia repair after abdominoperineal resection: a pooled analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e400-e406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yasukawa D, Aisu Y, Kimura Y, Takamatsu Y, Kitano T, Hori T. Which Therapeutic Option Is Optimal for Surgery-Related Perineal Hernia After Abdominoperineal Excision in Patients with Advanced Rectal Cancer? A Report of 3 Thought-Provoking Cases. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:663-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Artioukh DY, Smith RA, Gokul K. Risk factors for impaired healing of the perineal wound after abdominoperineal resection of rectum for carcinoma. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:362-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Beck DE, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, Lavery IC, McGonagle BA. Postoperative perineal hernia. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:21-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Martín Fernández J, Martin Duce A, Noguerales F, Lasa I, Granell J. Postoperative perineal hernia repairing technique. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:713-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | So JB, Palmer MT, Shellito PC. Postoperative perineal hernia. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:954-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Salum MR, Prado-Kobata MH, Saad SS, Matos D. Primary perineal posterior hernia: an abdominoperineal approach for mesh repair of the pelvic floor. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2005;60:71-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sarr MG, Stewart JR, Cameron JC. Combined abdominoperineal approach to repair of postoperative perineal hernia. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:597-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bell JG, Weiser EB, Metz P, Hoskins WJ. Gracilis muscle repair of perineal hernia following pelvic exenteration. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;56:377-380. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Giampapa V, Keller A, Shaw WW, Colen SR. Pelvic floor reconstruction using the rectus abdominis muscle flap. Ann Plast Surg. 1984;13:56-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Balla A, Batista Rodríguez G, Buonomo N, Martinez C, Hernández P, Bollo J, Targarona EM. Perineal hernia repair after abdominoperineal excision or extralevator abdominoperineal excision: a systematic review of the literature. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21:329-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sorelli PG, Clark SK, Jenkins JT. Laparoscopic repair of primary perineal hernias: the approach of choice in the 21st century. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e72-e73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ryan S, Kavanagh DO, Neary PC. Laparoscopic repair of postoperative perineal hernia. Case Rep Med. 2010;2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abbas Y, Garner J. Laparoscopic and perineal approaches to perineal hernia repair. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:361-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Douglas SR, Longo WE, Narayan D. A novel technique for perineal hernia repair. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Alam NN, Narang SK, Köckerling F, Daniels IR, Smart NJ. Biologic Mesh Reconstruction of the Pelvic Floor after Extralevator Abdominoperineal Excision: A Systematic Review. Front Surg. 2016;3:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Peacock O, Pandya H, Sharp T, Hurst NG, Speake WJ, Tierney GM, Lund JN. Biological mesh reconstruction of perineal wounds following enhanced abdominoperineal excision of rectum (APER). Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:475-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |