Published online Sep 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i17.3804

Peer-review started: May 14, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Revised: July 29, 2020

Accepted: August 14, 2020

Article in press: August 14, 2020

Published online: September 6, 2020

Processing time: 112 Days and 14.3 Hours

Hepatic portal venous gas in infants is frequently due to late presentation of necrotizing enterocolitis which is considered a relative indicator for surgical intervention.

A preterm baby underwent an umbilical catheter placement and discovered in abdominal radiograph to have air in the portal venous system due to malpositioning of the umbilical catheter.

Hepatic portal venous gas in infants without signs of necrotizing enterocolitis could result from malposition of umbilical venous catheter, and in that case, should be managed medically, with no need for surgical intervention.

Core tip: This is a case report of a rare case of a preterm baby with air in the portal venous system due to malpositioning of an umbilical catheter rather than necrotizing enterocolitis. Air in the portal venous system is very important in neonates, as it represents a late sign of necrotizing enterocolitis, and it is considered a relative indicator for surgical intervention. The aim of this case report is to deliver a massage to pediatric surgeons and neonatologists to be aware of this finding and not to rush for surgical intervention.

- Citation: Altokhais TI. Portal gas in neonates; is it always surgical? A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(17): 3804-3807

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i17/3804.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i17.3804

Air in the portal venous system is very important in neonates, as it represents a late sign of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), and it is considered a relative indicator for surgical intervention[1,2]. We report here a rare case of a preterm baby with air in the portal venous system due to malpositioning of an umbilical catheter rather than NEC.

A female neonate, with a post menstrual age of 27 wk and chronological age of 12 d, one of triplets and a product of in vitro fertilization, with a birth weight of 850 g, was referred for surgery as a case of NEC after observing air in the portal venous system.

The neonate was delivered and shifted to the neonatal care unit for management. She underwent umbilical catheter insertion. There were neither clinical nor radiological signs of NEC.

No remarkable past medical or surgical history.

The patient appeared clinically well, showing normal activity, and was tolerating feeds. There was no abdominal wall discoloration or distention.

There was no evidence of acidosis. C reactive protein was 2, platelets count was 200000, and white blood cells count was 12000. Capillary Blood gas was normal (pH: 7.37, Bicarbonate: 22). Blood sugar was 90 mg/dL and blood culture was negative.

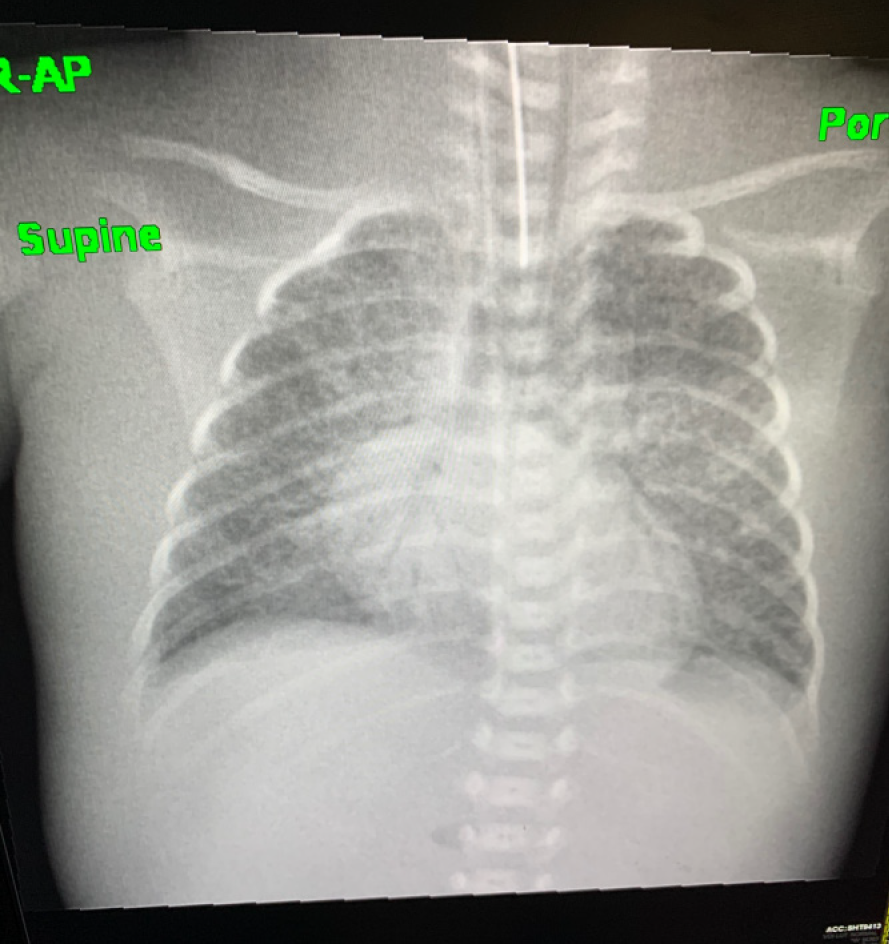

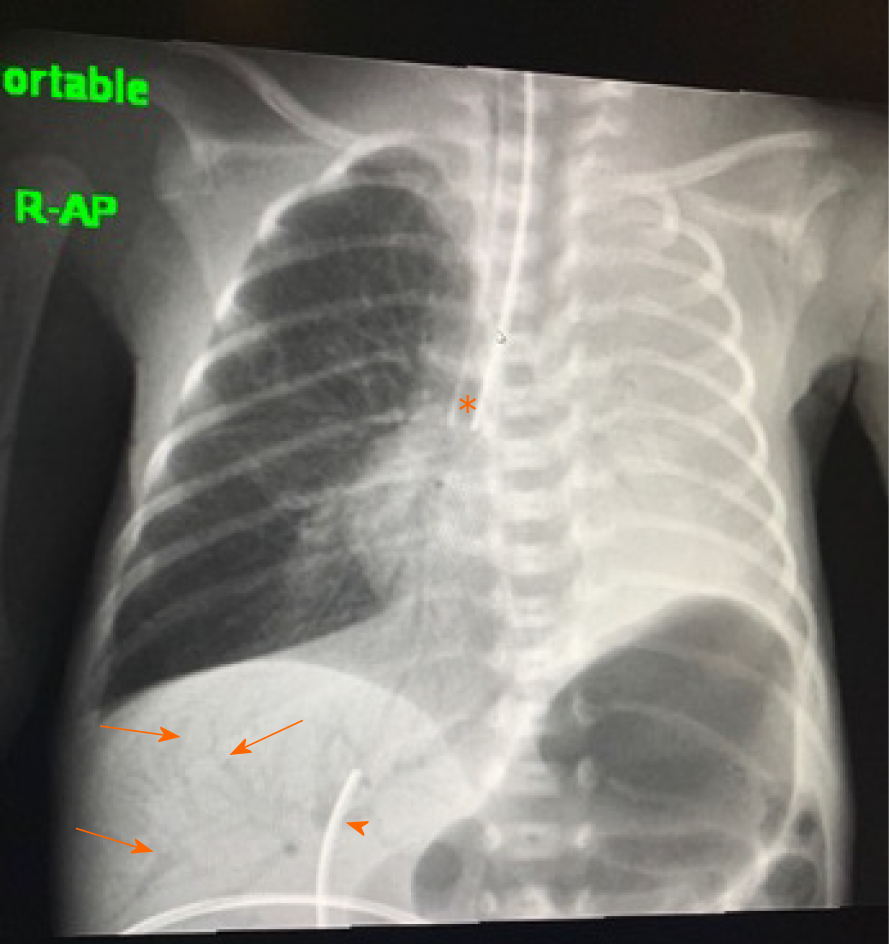

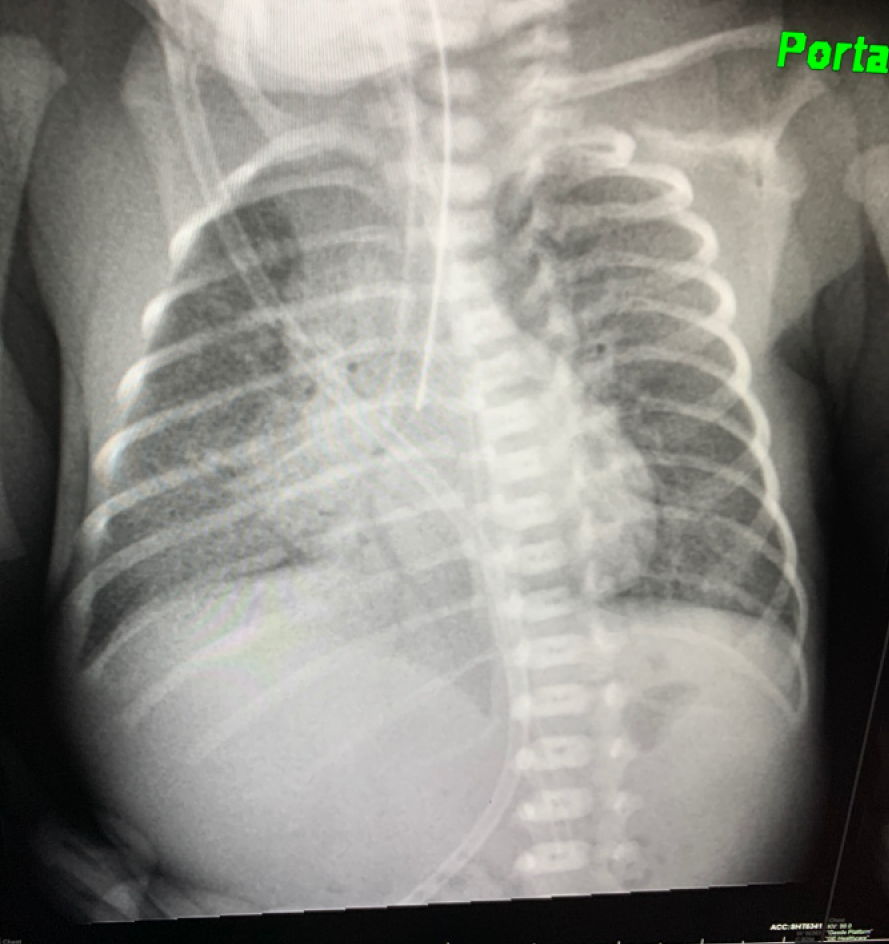

There was no air in the portal venous system before the insertion of umbilical catheter (Figure 1). But air in the portal venous system was noticed in the abdominal radiograph which was obtained to check the tip of the umbilical catheter (Figure 2). There was no pneumatosis intestinalis and bowel loops were not dilated. The umbilical catheter was removed, and the air in the portal venous system disappeared in the subsequent abdominal radiograph, which was performed after 24 h of adjustment (Figure 3).

The final diagnosis was an air in the portal venous system due to malpositioning of an umbilical catheter.

The umbilical catheter was removed and air disappeared.

The infant remained stable with no complication. She was managed medically and discharged home when her weight reached 1.8 kg.

Hepatic portal venous gas was first described by Wolfe et al[3] in neonates in 1955. There are many underlying abdominal conditions associated with portal venous gas, ranging from benign to fatal conditions[4]. When this finding is present with NEC, the infant is classified as at-risk with a high mortality rate (56%-90%) and might need surgical intervention[1,5]. Our case had no clinical or radiological signs of NEC; thus, she was observed and did not require surgical intervention.

The hepatic portal gas noticed in our case was due to improper umbilical catheter placement. Umbilical vascular catheter placement in neonates was first reported in 1947[6]. Although they are commonly used in the neonatal period, umbilical catheters are frequently malpositioned or associated with complications[7]. If the catheter is malpositioned, there can be complications such as perforation into the peritoneal cavity, perforation into the urachus, hepatic laceration, displacement of the thrombus in the ductus venosus, pulmonary infarction, perforation into the pericardium, a retained catheter fragment, lung abscess, splenic vein thrombosis, and calcification of the portal vein or umbilical vein[8].

Hepatic portal venous gas in radiography must be differentiated from gas in the biliary tree (pneumobilia). The classic radiological finding of portal venous gas is branching radiolucency following venous blood flow into the liver and extending to within 2 cm beneath the liver capsule. In contrast, pneumobilia is classically seen as central radiolucency following the biliary anatomy and not extending peripherally[1,4].

Hepatic portal venous gas in infants without signs of NEC could result from malposition of Umbilical venous catheter, and in that case, should be managed medically, with no need for surgical intervention.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Saudi Arabia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Patel J, Wang KW S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Derinkuyu BE, Boyunaga OL, Damar C, Unal S, Ergenekon E, Alimli AG, Oztunali C, Turkyilmaz C. Hepatic Complications of Umbilical Venous Catheters in the Neonatal Period: The Ultrasound Spectrum. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37:1335-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Robinson JR, Rellinger EJ, Hatch LD, Weitkamp JH, Speck KE, Danko M, Blakely ML. Surgical necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41:70-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wolfe JN, Evans WA. Gas in the portal veins of the liver in infants; a roentgenographic demonstration with postmortem anatomical correlation. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1955;74:486-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abboud B, El Hachem J, Yazbeck T, Doumit C. Hepatic portal venous gas: physiopathology, etiology, prognosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3585-3590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Thakkar HS, Lakhoo K. The surgical management of necrotising enterocolitis (NEC). Early Hum Dev. 2016;97:25-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Diamond LK. Erythroblastosis foetalis or haemolytic disease of the newborn. Proc R Soc Med. 1947;40:546-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schlesinger AE, Braverman RM, DiPietro MA. Pictorial essay. Neonates and umbilical venous catheters: normal appearance, anomalous positions, complications, and potential aid to diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1147-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Oestreich AE. Umbilical vein catheterization--appropriate and inappropriate placement. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1941-1949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |