Published online Sep 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i17.3679

Peer-review started: January 3, 2020

First decision: January 18, 2020

Revised: May 15, 2020

Accepted: August 1, 2020

Article in press: August 1, 2020

Published online: September 6, 2020

Processing time: 244 Days and 14.9 Hours

There are no studies on incidental anal 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) uptake.

To assess the rate and aetiologies of incidental anal 18FDG uptake and to evaluate the correlation between 18FDG positron-emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) parameters and the diagnosis of an anorectal disease.

The data from patients with incidental anal 18FDG uptake were retrospectively analysed. Patients who underwent anorectal examinations were identified and compared to those who did not undergo examinations. Patients who were offered treatment were then identified and compared to those who did not receive treatment.

Among the 43020 18FDG PET/CT scans performed, 197 18FDG PET/CT scans of 146 patients (0.45%) reported incidental anal uptake. Among the 134 patients included, 48 (35.8%) patients underwent anorectal examinations, and anorectal diseases were diagnosed in 33 (69.0%) of these patients and treated in 18/48 (37.5%) patients. Among the examined patients, those with a pathology requiring treatment had significantly smaller metabolic volumes (MV) 30 and MV41 values and higher maximal and mean standardized uptake value measurements than those who did not require treatment.

Incidental anal 18FDG uptake is rare, but a reliable anorectal diagnosis is commonly obtained when an anorectal examination is performed. The diagnosis of an anorectal disease induces treatment in more than one-third of the patients. These data should encourage practitioners to explore incidental anal 18FDG uptake systematically.

Core tip: This is a retrospective study to assess the rate and aetiologies of incidental anal 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) uptake and to evaluate the correlation between 18FDG positron-emission tomography/computed tomography parameters and the diagnosis of an anorectal disease. Incidental anal 18FDG uptake is rare, but a reliable anorectal diagnosis is commonly obtained when an anorectal examination is performed. The diagnosis of an anorectal disease induces treatment in more than one-third of the patients. These data should encourage practitioners to explore incidental anal 18FDG uptake systematically.

- Citation: Moussaddaq AS, Brochard C, Palard-Novello X, Garin E, Wallenhorst T, Le Balc’h E, Merlini L’heritier A, Grainville T, Siproudhis L, Lièvre A. Incidental anal 18fluorodeoxyglucose uptake: Should we further examine the patient? World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(17): 3679-3690

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i17/3679.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i17.3679

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) positron-emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) is a medical imaging technique based on the study of glucose metabolism. The use of this method has increased in oncology for the initial staging of cancer, monitoring treatment response and detecting early recurrence of a previously treated malignant tumour[1]. It is also used in the management of infectious or inflammatory diseases[2]. As a result of the increased indications for and availability of 18FDG PET/CT, unexpected 18FDG uptake has been identified in a variety of sites[3-6]. In the field of gastroenterology, several studies have focused on colorectal locations[7-17]. Incidental focal colorectal 18FDG uptake on 18FDG PET/CT imaging was associated with endoscopic lesions in two-thirds of the cases, with a high rate of advanced neoplasms[7], but no metabolic parameter has been identified to distinguish neoplasms from benign lesions[7,18]. Thus, a complete colonoscopy tends to be recommended for all patients.

Within the field of gastroenterology, no studies to date have investigated incidental anal 18FDG uptake. However, anorectal examinations are nevertheless simple and minimally invasive, and the diagnosis of anal pathologies is often based on the patient’s history or data obtained during the clinical examination. It seems important then to assess the rate of incidental anal 18FDG uptake and to identify their aetiologies. Finally, no recommendations have been established in this particular situation.

The aims of this study were as follows: (1) To assess the rate of incidental anal 18FDG uptake; (2) To identify the aetiologies of incidental anal 18FDG uptake; and (3) To evaluate the correlation between 18FDG PET/CT parameters and the diagnosis of an anorectal disease and the management of the disease.

The database of 18FDG PET/CT scans from a tertiary referral centre of nuclear medicine (January 2005 and December 2018) was reviewed. Among 43020 18FDG PET/CT reports, those containing the terms “anal” or “anus” were identified. Then, we selected examinations with incidental anal 18FDG uptake. Patients with personal histories of anal cancer were excluded. Patients with a history of pelvic radiation within 3 months or anal surgery within 6 weeks before the 18FDG PET/CT were also excluded. The patient demographic data, past medical histories, indications for 18FDG PET/CT and results concerning the initial oncological pathology report were extracted from the database.

The patients fasted for at least 4 hours before 18FDG PET/CT imaging. The blood glucose level was controlled before the FDG injection. The acquisition ranged from the base of the skull to the proximal thighs and was performed 60 to 90 min after an intravenous injection of FDG. From January 2005 to May 2016, 18FDG PET/CT exams were performed with a hybrid PET/CT scanner (Discovery LS, GE Medical Systems Inc., Waukesha, WI, United States) after an intravenous injection of 4 MBq/kg FDG. From June 2016 to December 2018, 18FDG PET/CT exams were performed with a hybrid PET/CT scanner (Siemens Biograph system, Siemens, Knoxville, TN, United States) after an intravenous injection of 3 MBq/kg FDG. For both PET systems, the data were reconstructed using an ordered-subsets expectation maximization iterative algorithm with corrections (attenuation, dead time, randoms, scatter, and decay). The standardized uptake value (SUV) was calculated and adjusted by the mean injected dose according to the tissue activity concentration and patient body weight. To include patients with focal incidental anal 18FDG uptake, all 18FDG PET/CT images from patients identified with incidental anal uptake were retrospectively reassessed by a nuclear medicine physician at the Department of Nuclear Medicine who was blinded to the anorectal findings. Anal 18FDG uptake was defined as uptake located in the anal canal relative to the background activity. Incidental anal 18FDG uptake was defined by the existence of anal hyperfixation in patients with no known anal pathology before the 18FDG PET/CT. A 3-D volume of interest (VOI) was manually drawn to extract metabolic parameters (Syngo.via software; Siemens). The metabolic parameters extracted were the SUVmax (the highest SUV of all SUVs measured in the VOI), SUVmean (the mean of all SUVmean measurements from the tumour VOIs with a local SUVmax threshold of 41%), and different metabolic volumes (MVs) defined as the volume produced by segmentation at the following fixed SUVmax thresholds: 50% (MV50), 41% (MV41), and 30% (MV30)[1,14]. In patients with anal uptake described on several 18FDG PET/CT scans, the metabolic parameters selected were those that corresponded to the 18FDG PET/CT with the largest SUVmax.

The data about management after the discovery of incidental anal 18FDG uptake were collected from the patient records from the Department of Nuclear Medicine. The data were compared with the patient records from the general practitioner and/or the specialist, if applicable.

The data collected from patients who further investigated were as follows: Symptoms, practitioner who performed the evaluation (oncologist, radiotherapist, surgeon, gastroenterologist, or colorectal specialist), evaluation modality (rectal examination, anoscopy), further examinations (CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging, endoanal ultrasound, and examinations under general anaesthesia, colonoscopy, or histology) and results, if available. The diagnosis was recorded and classified as follows: Haemorrhoidal disease, anal fissure, neoplasia, fistula, anal condyloma, or other diagnosis. Each proctologic report was reviewed by a specialist in proctology from the University Hospital of Rennes. Treatments were offered in case of symptomatic disease or if there was a risk of extension and/or aggravation of the disease. The treatment was chosen according to the habits of the practitioner. Patients who were offered treatment were identified and compared to those who were not treated. The proposed treatments were collected.

Among the patients with incidental anal 18FDG uptake, the patient data were compared according to the occurrence of anorectal investigations.

The quantitative variables are presented as means and percentiles (interquartile range of 25% and 75%). The qualitative variables are presented as numbers and percentages. The qualitative variables were compared using χ2 tests or Fischer’s exact tests, as appropriate. The quantitative variables were compared using the non-parametric Wilcoxon’s test. Comparisons between patients who underwent examinations with those who had not were performed using the Wilcoxon test and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The same tests were applied to compare patients who were offered treatment with those who were not. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To measure the discriminatory accuracy of SUV and MV for diagnostic and therapeutic management, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed, and the area under the ROC curve (AUROC) was calculated. Logistic regression analysis was performed with independent categorical items obtained at P < 0.05 by univariate analysis using a forward method to identify factors associated to treatment. Pearson correlation coefficients and Fisher tests were performed to verify whether the Pearson coefficients were significantly different from 0. The tests were performed using JMP Pro software, version 13.0.0 (SAS, Cary, NC, United States).

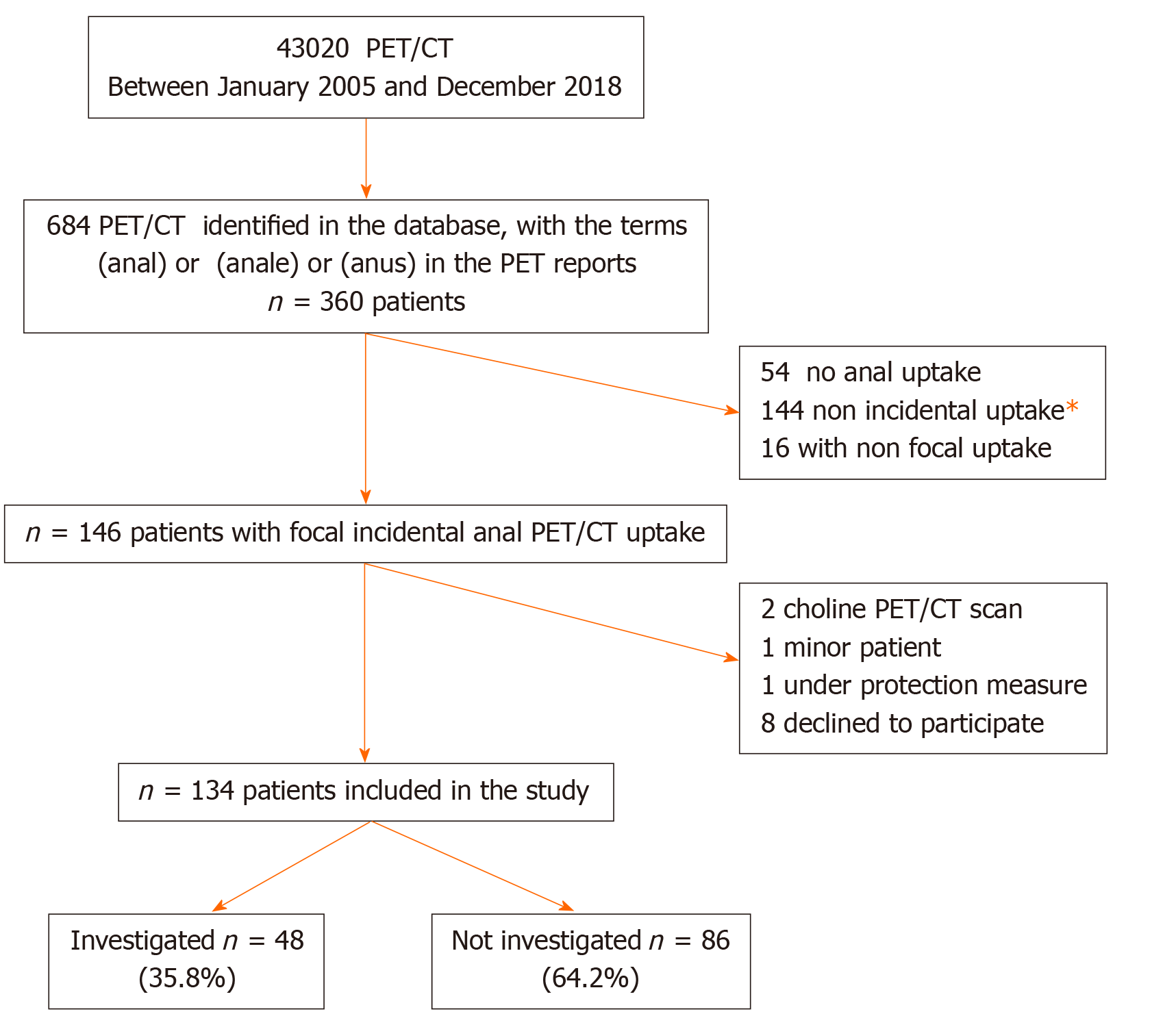

Among the 43020 18FDG PET/CT scans performed between January 2005 and December 2018, 197 18FDG PET/CT of 146 patients reported incidental anal uptake. Twelve patients were excluded; finally, 134 patients were included in the study (Figure 1). The patient characteristics and 18FDG PET/CT indications are summarized in Table 1. Twenty-one (15.7%) patients had the following past anorectal histories: Haemorrhoidal disease (7.8%), anal fistula (4.7%), anal fissure (1.6%), anal condyloma (1.6%), and faecal incontinence (0.7%).

| Variables | Global population | Patients non investigated | Patients investigated | P value |

| n (%) or mean ± SD | n (%) or mean ± SD | n (%) or mean ± SD | ||

| n = 134 | n = 86 | n = 48 | ||

| Age (yr) | 61.3 (12.8) | 61.0 (12.1) | 61.9 (14.1) | 0.69 |

| Gender (male) | 84 (62.7) | 56 (65.1) | 28 (58.3) | 0.43 |

| 18FDG PET/CT indications | 0.42 | |||

| Diagnosis | 20 (14.9) | 10 (11.6) | 10 (20.8) | |

| Follow-up of a known cancer | 47 (35.1) | 32 (37.2) | 15 (31.3) | |

| Staging of a known cancer | 45 (33.6) | 32 (37.2) | 13 (27.1) | |

| Suspicion of cancer recurrence | 17 (12.7) | 9 (10.5) | 8 (16.7) | |

| Diagnosis of infectious/inflammatory disease | 5 (3.7) | 3 (3.5) | 2 (4.2) | |

| Primitive cancer | 0.13 | |||

| Hematological cancer | 22 (16.4) | 17 (20.0) | 5 (10.5) | |

| Head and neck cancer | 14 (10.4) | 9 (10.5) | 5 (10.4) | |

| Lung cancer | 25 (18.6) | 21 (24.4) | 4 (8.3) | |

| Gynecological cancer | 22 (16.4) | 13 (15.1) | 9 (18.8) | |

| Urological cancer | 4 (3.0) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (6.3) | |

| Digestive cancer | 14 (10.5) | 8 (3.5) | 6 (12.5) | |

| Melanoma | 9 (6.7) | 5 (5.8) | 4 (8.3) | |

| Others1 | 7 (5.2) | 3 (3.5) | 4 (8.3) | |

| Past history of pelvic radiotherapy2 | 13 (9.7) | 8 (9.3) | 5 (10.4) | 0.83 |

| Past history of proctologic diseaseb | 21 (15.7) | 6 (7.0) | 15 (31.3) | 0.0002 |

| 18FDG PET/CT | ||||

| SUV mean | 5.5 (2.3) | 5.3 (2.1) | 5.9 (2.6) | 0.15 |

| SUV max | 9.6 (3.9) | 9.2 (3.5) | 10.2 (4.5) | 0.13 |

| MV50 (cm3) | 4.1 (2.8) | 4.2 (3.0) | 4.0 (2.3) | 0.65 |

| MV41 (cm3) | 6.6 (4.2) | 6.7 (4.6) | 6.4 (3.5) | 0.64 |

| MV 30 (cm3) | 11.9 (7.1) | 12.2 (7.7) | 11.4 (5.9) | 0.51 |

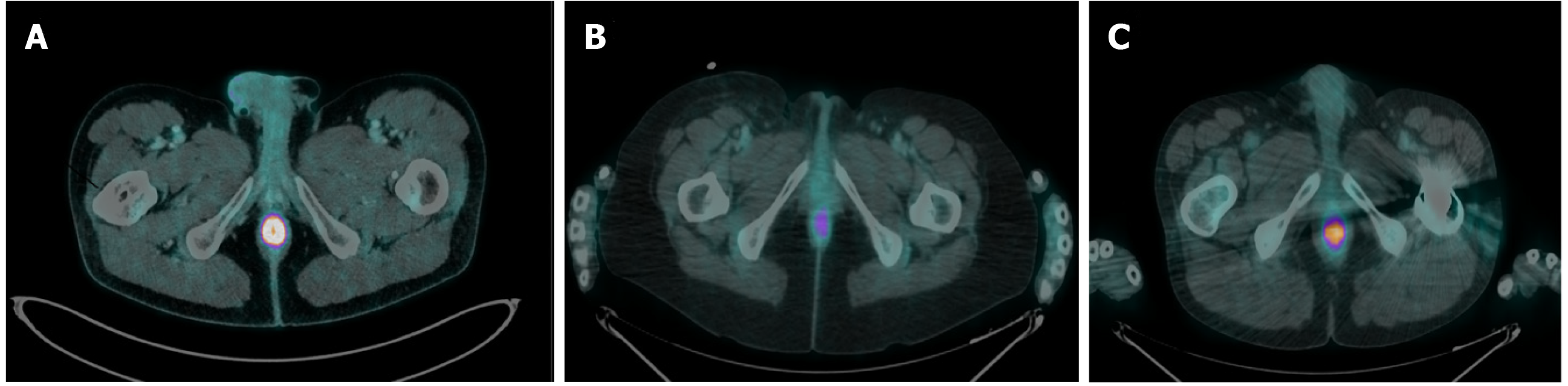

Among the 134 patients with incidental anal 18FDG uptake, 48 (35.8%) underwent anorectal examinations to explore the anomaly. The characteristics of the patients who underwent examinations are depicted in Table 1 and Table 2. The patients were examined most frequently by a colorectal specialist (62.5%) or a gastroenterologist (20.8%). The clinical examinations ranged from a simple inspection of the anal margin (95.8%) to anoscopy (51.1%). More than half (54.2%) of the patients had at least one other examination. Patients who underwent examinations were compared with those who did not undergo examinations (Table 1). The two groups were comparable in terms of age, sex, indication for 18FDG PET/CT, primitive cancer, history of pelvic radiotherapy and 18FDG PET/CT metabolic parameters. Patients who underwent examinations more frequently had a past history of anorectal disease than those who did not undergo examinations (P = 0.0002). Among the 48 patients who underwent examinations, 33 (69%) had the following anorectal diseases: Haemorrhoidal disease (n = 19), anal fissure (n = 6), recurrence of rectal adenocarcinoma on the coloanal anastomosis (n = 2), condyloma (n = 3), faecal impaction (n = 1), suppuration (n = 1) and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (n = 1) (Figure 2).

| All | No treatment offered | Treatment offered | P value | |

| n (%) or mean ± SD | n (%) or mean ± SD | n (%) or mean ± SD | ||

| n = 48 | n = 30 | n = 18 | ||

| Assessmenta by | 0.0457 | |||

| Proctologist | 30 (62.5) | 15 (50.0) | 15 (83.3) | |

| Gastroenterologist | 10 (20.8) | 7 (23.3) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Oncologist | 2 (4.2) | 2 (6.7) | ||

| Radiotherapist | 5 (10.4) | 5 (16.7) | ||

| Surgeon | 1 (2.1) | 1 (3.3) | ||

| Examination | ||||

| Anal margin | 46 (95.8) | 29 (96.7) | 17 (94.4) | 0.71 |

| Rectal digital examination | 40 (85.2) | 25 (86.2) | 15 (83.3) | 0.78 |

| Anoscopy | 24 (51.1) | 12 (41.4) | 12 (66.7) | 0.09 |

| Colonoscopy | 17 (36.2) | 11 (38.0) | 6 (33.3) | 0.75 |

| Examination under general anesthesiaa | 5 (10.6) | 1 (3.5) | 4 (22.2) | 0.04 |

| Biopsies | 8 (17.0) | 3 (10.3) | 5 (27.8) | 0.12 |

| Endoanal ultrasound | 7 (14.9) | 5 (17.2) | 2 (11.1) | 0.56 |

| Pelvic MRI | 2 (4.3) | 1 (3.5) | 1 (5.6) | 0.73 |

| Symptom | 19 (40.4) | 9 (31.0) | 10 (58.8) | 0.06 |

| 18FDG PET/CT | ||||

| SUV meana | 5.9 (2.6) | 5.2 (1.9) | 7.2 (3.2) | 0.02 |

| SUV maxa | 10.2 (4.5) | 9.0 (3.3) | 12.4 (5.4) | 0.02 |

| MV50 | 4.0 (2.3) | 4.4 (2.4) | 3.3 (2.0) | 0.13 |

| MV41 | 6.4 (3.5) | 7.2 (3.6) | 5.1 (3.0) | 0.05 |

| MV 30a | 11.4 (6.0) | 12.9 (6.3) | 8.9 (4.4) | 0.03 |

| Diagnosis of a proctological diseaseb | 33 (68.8) | 15 (50.0) | 18 (100.0) | 0.003 |

| Haemorrhoidal disease | 19 | 2 | 12 | |

| Anal fissure | 6 | 1 | 5 | |

| Recurrence of rectal adenocarcinoma | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Condyloma | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Fecal impaction | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Anal suppuration | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Treatment | 18 (37.5) | 18 (100) | ||

| Medical treatment | 11 (61.1) | |||

| Surgical treatment | 5 (27.8) | |||

| Medical and instrumental treatments | 1 (5.6) | |||

| Endoscopic treatment | 1 (5.6) |

In our study group, no metabolic parameters were significantly associated with the presence or absence of a diagnosis; likewise, there were no significant differences between anorectal diseases according to the metabolic parameters.

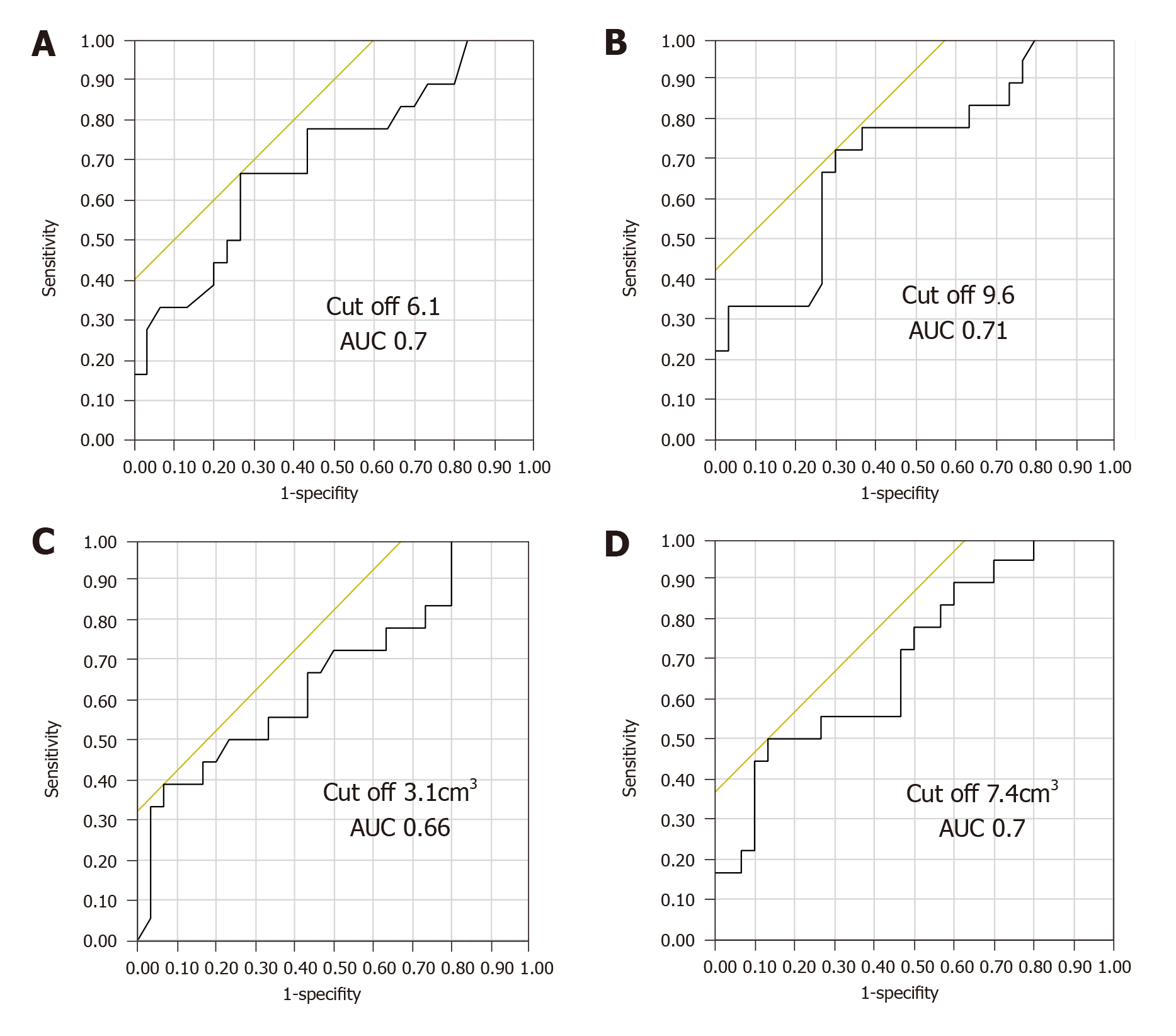

Among the 48 patients who underwent examinations, 18 (37.5%) were offered treatment (Table 3). The characteristics of the treated patients were compared with those of the untreated patients and are depicted in Table 2. All patients who received treatment had more frequent complaints than those who did not receive treatment and were examined by colorectal specialists or gastroenterologists. Of the asymptomatic patients, 18/29 were diagnosed [haemorrhoidal disease (n = 12), anal fissure (n = 2), condyloma (n = 3) and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (n = 1)] and 8/29 were offered treatment. Among the 29 asymptomatic patients, the 18FDG PET/CT metabolic parameters differed significantly between treated and untreated patients. The group of asymptomatic patients that was offered treatment had higher SUVmax and SUVmean measurements (P = 0.03 for both) and lower MV41 and MV30 values than the group asymptomatic patients without treatment (P = 0.02 and P = 0.03, respectively). Among the 15 patients with progressive PET-CT (considered poor prognosis), 8 had treatment and 7 had no treatment (P = 0.46). The 18FDG PET/CT metabolic parameters differed significantly between treated and untreated patients. The group of patients that was offered treatment had higher SUVmax and SUVmean measurements (P = 0.02 for both) and lower MV41 and MV30 values than the group without treatment (P = 0.05 and P = 0.03, respectively). The ROC curves of the SUVmax, SUVmean, MV41 and MV30 as predictive factors for the treatment of examined incidental anal 18FDG uptake are shown in Figure 3. According to the ROC curves, the optimal cut-off for SUVmax, SUVmean, MV41 and MV30 were 9.6, 6.1, 3.1 cm³ and 7.4 cm³, respectively. The SUVmax measurements were inversely correlated with MV41 (r = -0.27, P = 0.0006) and MV30 (r = -0.18, P = 0.0002). In a multivariate analysis including the presence of symptoms, the diagnosis (yes) and the SUV mean > 6.1 cm3, the factor significantly associated with the treatment was the SUV mean > 6.1 cm3 [OR = 6.87 (1.18-29.9), P = 0.03].

| n (%) | |

| Total | 18 (100) |

| Medical treatment | 11 (61.1) |

| Transit regulator | 4 (22.2) |

| Oral analgesic treatment | 1 (5.6) |

| Topical treatment | 8 (44.4) |

| Treatment of hemorrhoids | 4 (22.2) |

| 5-aminosalicylic acid | 1 (5.6) |

| Antibiotic (metronidazole) | 1 (5.6) |

| Botulinum toxin injection | 1 (5.6) |

| Healing cream | 1 (5.6) |

| Surgical treatment | 5 (27.9) |

| Electrocoagulation of condyloma | 1 (5.6) |

| Surgery of hemorrhoids | 2 (11.1) |

| Fissurectomy | 1 (5.6) |

| Posterior pelvectomy | 1 (5.6) |

| Instrumental and medical treatment | |

| Infrared coagulation and imiquimod | 1 (5.6) |

| Endoscopic treatment | |

| Hydraulic dilatation | 1 (5.6) |

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the rate of incidental anal 18FDG uptake and its diagnostic and therapeutic impact in a large series of 18FDG PET/CT scans performed over a 14-year period.

The present work highlights that incidental anal 18FDG uptake is a rare event (0.45%) and is not systematically explored (36%). When examinations are performed, an anorectal disease was diagnosed in more than two-thirds of the patients (69%), and a specific treatment was proposed in almost 40% of these patients. Finally, we identified some metabolic parameters (SUVmax, SUVmean, MV41 and MV30) significantly associated with anorectal treatment, with SUVmax having the best accuracy. Taken together, our data suggest that, although it is not frequent, incidental anal 18FDG uptake should require anorectal examinations given its high diagnostic and therapeutic impact.

The main strengths of this work are the inclusion of a large number of 18FDG PET/CT scans requested for various indications over a long period of time, reassessment of 18FDG PET/CT images by a physician who was blinded to anorectal findings and exhaustiveness of the anorectal data collection. As previously mentioned, this is also, to the best of our knowledge, the first study to investigate the rate and management of incidental anal 18FDG uptake.

In our series, incidental anal 18FDG uptake was investigated in 36% of the patients, which means that it was not been taken into account in almost two-thirds of the patients. Several explanations are possible. First, incidental anal 18FDG uptake was not mentioned in the conclusion but only in the details of the 18FDG PET/CT report of many patients (58%), which suggests that many nuclear physicians considered this 18FDG uptake to be non-clinically significant in the absence of data in the current literature. Furthermore, very few reports of consultations with the referring physician who prescribed the 18FDG PET/CT mentioned the anal 18FDG uptake, which may be explained by the following points: (1) No mention of the anal 18FDG uptake in the conclusion of the 18FDG/PET CT report; (2) The physician (an oncologist in the majority of cases) considered that the anal 18FDG uptake was secondary compared to the pathology that motivated the 18FDG PET/CT (tumour diagnosis, recurrence or progression), regardless of whether the patients underwent examinations, and was comparable in each setting and (3) The physician did not dare to discuss this abnormality with the patient or the patient refused to be examined, as we know that anorectal complaints and examinations remain a taboo subject for both patients and physicians.

Importantly, patients who were examined underwent a specific anorectal treatment in almost 40% of the cases, including surgery in 28% (5/18) of these cases. Therefore, it seems justified to systematically seek anorectal complaints and propose an anorectal examination, which should include at least an anal margin and rectal digital examination. This first assessment is simple and minimally invasive and makes it possible to evaluate if the patient needs to be referred to a specialist. However, this strategy cannot assess haemorrhoidal diseases with enough sensitivity. Notably, 40% of the examined patients in the present study had anorectal symptoms, which emphasizes the importance of a obtaining a good patient history to identify those who need to be directly addressed to a colorectal specialist.

Our study identified SUV and MV measurements as factors associated with the anorectal examination having a therapeutic impact, with SUVmax having the best accuracy. Interestingly, patients who received treatment had significantly lower MV30 and MV41 values and higher SUVmax and SUVmean measurements than patients who did not receive treatment. These conclusions are different from those of colorectal positive uptake. In the studies on incidental focal colorectal 18FDG uptake on 18FDG PET/CT images, the metabolic parameters could not differentiate between true positives and false positives, with acceptable sensitivity and specificity, and therefore had no diagnostic or therapeutic impact[7,17-19].

In our study, the diagnoses correspond more to inflammatory or infectious processes than to other conditions. In this field, the diagnostic, therapeutic or prognostic impact of metabolic parameters has not been identified, except for SUVmax, which has been shown to have a prognostic impact on cardiovascular events and corticosteroid response in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis[20]. However, in oncology, the metabolic tumour volume (MTV) has a prognostic impact on diseases in several locations (head and neck cancers or anal cancers, for example), with a prognosis that worsens as the MTV increases[1,21-27], which is sometimes also the case for SUVmax[28-31]. These parameters also have a role in monitoring therapy response[1,32-34]. Paradoxically, our results showed that smaller MVs are associated with treatment. We have not found any similar cases in the literature. Additionally, a lesion does not necessarily require more treatment because it has a larger volume.

Our study results, however, should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. The main limitations of this study are its retrospective and monocentric design. Moreover, it is possible that the rate of anal 18FDG uptake we reported is underestimated because it cannot be excluded that this anomaly is not systematically described by all nuclear physicians, given the lack of clinical significance described so far. In addition, 62% of the patients included did not undergo anorectal examinations; thus, the aetiology of their anal 18FDG uptake remains unknown. It would have also been interesting to investigate a control group of patients without anal 18FDG uptake to better demonstrate the diagnostic and therapeutic impact of anal 18FDG uptake. In our study, the proportions of patients who underwent examinations and those who received treatment were low, which led to a lack of power, even though this is the largest series reported. Due to the small sample size, we were unable to analyse the relationship between metabolic parameters and a precise diagnosis. The role of haemorrhoidal disease in anal 18FDG uptake remains somewhat speculative since haemorrhoids cushions are a normal compound of anal anatomy. Finally, symptomatic complaints not recorded (retrospective analyses) may bias the results (high proportion of treated anorectal lesions).

In conclusion, incidental anal 18FDG uptake is a rare event and is rarely explored. However, when explored, a diagnosis is made in more than two-thirds of the cases, and treatment is proposed in more than one-third of the cases. Some metabolic parameters associated with a therapeutic impact have been identified. These data should encourage practitioners to explore incidental anal 18FDG uptake systematically because some patients may recover well from an anal pathology.

The use of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) positron-emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) has increased in oncology and in the management of infectious or inflammatory diseases. As a result of the increased indications for and availability of 18FDG PET/CT, unexpected 18FDG uptake has been identified in a variety of sites. In the field of gastroenterology, several studies have focused on incidental focal colorectal 18FDG uptake. No studies to date have investigated incidental anal 18FDG uptake. Anorectal examinations are nevertheless simple and minimally invasive, and the diagnosis of anal pathologies is often based on the patient’s history or data obtained during the clinical examination.

It seems important to assess the rate of incidental anal 18FDG uptake and to identify their aetiologies. Finally, no recommendations have been established in this particular situation.

The objectives of this study were as follows to assess the rate of incidental anal 18FDG uptake, to identify the aetiologies of incidental anal 18FDG uptake, and to evaluate the correlation between 18FDG PET/CT parameters and the diagnosis of an anorectal disease and the management of the disease.

We carried out a retrospective observational single-centre study. The data from patients with incidental anal 18FDG uptake were analysed. Patients who underwent anorectal examinations were identified and compared to those who did not undergo examinations. Patients who were offered treatment were then identified and compared to those who did not receive treatment. Comparisons between patients were performed using the Wilcoxon test and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Among the 43020 18FDG PET/CT scans performed, 197 18FDG PET/CT scans of 146 patients reported incidental anal uptake: The rate of incidental anal 18FDG uptake was 0.45%. Among the 134 patients included, 48 (35.8%) patients underwent anorectal examinations and anorectal diseases were diagnosed in 33 (69.0%) of these patients haemorrhoidal disease (n = 22), anal fissure (n = 6), recurrence of rectal adenocarcinoma on the coloanal anastomosis (n = 1), condyloma (n = 3), faecal impaction (n = 1), suppuration (n = 2) and solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (n = 1). Eighteen/48 (37.5%) received treatment. Among the examined patients, those with a pathology requiring treatment had significantly smaller metabolic volumes (MV) 30 and MV41 values and higher maximal and mean standardized uptake value measurements than those who did not require treatment.

Incidental anal 18FDG uptake is a rare event and is rarely explored. However, when explored, a diagnosis is made in more than two-thirds of the cases, and treatment is proposed in more than one-third of the cases. Some metabolic parameters associated with a therapeutic impact have been identified. These data should encourage practitioners to explore incidental anal 18FDG uptake systematically because some patients may recover well from an anal pathology.

Further large-scale prospective studies are needed. We would like to investigate a control group of patients without anal 18FDG uptake to better demonstrate the diagnostic and therapeutic impact of anal 18FDG uptake.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: France

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Afzal M, Kuwai T S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Boellaard R, Delgado-Bolton R, Oyen WJ, Giammarile F, Tatsch K, Eschner W, Verzijlbergen FJ, Barrington SF, Pike LC, Weber WA, Stroobants S, Delbeke D, Donohoe KJ, Holbrook S, Graham MM, Testanera G, Hoekstra OS, Zijlstra J, Visser E, Hoekstra CJ, Pruim J, Willemsen A, Arends B, Kotzerke J, Bockisch A, Beyer T, Chiti A, Krause BJ; European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). FDG PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour imaging: version 2.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:328-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2053] [Cited by in RCA: 2282] [Article Influence: 228.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jamar F, Buscombe J, Chiti A, Christian PE, Delbeke D, Donohoe KJ, Israel O, Martin-Comin J, Signore A. EANM/SNMMI guideline for 18F-FDG use in inflammation and infection. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:647-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Agress H, Cooper BZ. Detection of clinically unexpected malignant and premalignant tumors with whole-body FDG PET: histopathologic comparison. Radiology. 2004;230:417-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Even-Sapir E, Lerman H, Gutman M, Lievshitz G, Zuriel L, Polliack A, Inbar M, Metser U. The presentation of malignant tumours and pre-malignant lesions incidentally found on PET-CT. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:541-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ishimori T, Patel PV, Wahl RL. Detection of unexpected additional primary malignancies with PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:752-757. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Pencharz D, Nathan M, Wagner TL. Evidence-based management of incidental focal uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose on PET-CT. Br J Radiol. 2018;91:20170774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rigault E, Lenoir L, Bouguen G, Pagenault M, Lièvre A, Garin E, Siproudhis L, Bretagne JF. Incidental colorectal focal 18 F-FDG uptake: a novel indication for colonoscopy. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E924-E930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Şimşek FS, İspiroğlu M, Taşdemir B, Köroğlu R, Ünal K, Özercan IH, Entok E, Kuşlu D, Karabulut K. What approach should we take for the incidental finding of increased 18F-FDG uptake foci in the colon on PET/CT? Nucl Med Commun. 2015;36:1195-1201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tatlidil R, Jadvar H, Bading JR, Conti PS. Incidental colonic fluorodeoxyglucose uptake: correlation with colonoscopic and histopathologic findings. Radiology. 2002;224:783-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Salazar Andía G, Prieto Soriano A, Ortega Candil A, Cabrera Martín MN, González Roiz C, Ortiz Zapata JJ, Cardona Arboniés J, Lapeña Gutiérrez L, Carreras Delgado JL. Clinical relevance of incidental finding of focal uptakes in the colon during 18F-FDG PET/CT studies in oncology patients without known colorectal carcinoma and evaluation of the impact on management. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2012;31:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Goldin E, Mahamid M, Koslowsky B, Shteingart S, Dubner Y, Lalazar G, Wengrower D. Unexpected FDG-PET uptake in the gastrointestinal tract: endoscopic and histopathological correlations. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4377-4381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Israel O, Yefremov N, Bar-Shalom R, Kagana O, Frenkel A, Keidar Z, Fischer D. PET/CT detection of unexpected gastrointestinal foci of 18F-FDG uptake: incidence, localization patterns, and clinical significance. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:758-762. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Treglia G, Taralli S, Salsano M, Muoio B, Sadeghi R, Giovanella L. Prevalence and malignancy risk of focal colorectal incidental uptake detected by (18)F-FDG-PET or PET/CT: a meta-analysis. Radiol Oncol. 2014;48:99-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Keyzer C, Dhaene B, Blocklet D, De Maertelaer V, Goldman S, Gevenois PA. Colonoscopic Findings in Patients With Incidental Colonic Focal FDG Uptake. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:W586-W591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shmidt E, Nehra V, Lowe V, Oxentenko AS. Clinical significance of incidental [18 F]FDG uptake in the gastrointestinal tract on PET/CT imaging: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kamel EM, Thumshirn M, Truninger K, Schiesser M, Fried M, Padberg B, Schneiter D, Stoeckli SJ, von Schulthess GK, Stumpe KD. Significance of incidental 18F-FDG accumulations in the gastrointestinal tract in PET/CT: correlation with endoscopic and histopathologic results. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1804-1810. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Gauthé M, Richard-Molard M, Cacheux W, Michel P, Jouve JL, Mitry E, Alberini JL, Lièvre A; Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive (FFCD). Role of fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in gastrointestinal cancers. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:443-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gutman F, Alberini JL, Wartski M, Vilain D, Le Stanc E, Sarandi F, Corone C, Tainturier C, Pecking AP. Incidental colonic focal lesions detected by FDG PET/CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:495-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | van Hoeij FB, Keijsers RG, Loffeld BC, Dun G, Stadhouders PH, Weusten BL. Incidental colonic focal FDG uptake on PET/CT: can the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) guide us in the timing of colonoscopy? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:66-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tuominen H, Haarala A, Tikkakoski A, Kähönen M, Nikus K, Sipilä K. FDG-PET in possible cardiac sarcoidosis: Right ventricular uptake and high total cardiac metabolic activity predict cardiovascular events. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gauthé M, Richard-Molard M, Fayard J, Alberini JL, Cacheux W, Lièvre A. Prognostic impact of tumour burden assessed by metabolic tumour volume on FDG PET/CT in anal canal cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dibble EH, Alvarez AC, Truong MT, Mercier G, Cook EF, Subramaniam RM. 18F-FDG metabolic tumor volume and total glycolytic activity of oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer: adding value to clinical staging. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:709-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu J, Dong M, Sun X, Li W, Xing L, Yu J. Prognostic Value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in Surgical Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bazan JG, Koong AC, Kapp DS, Quon A, Graves EE, Loo BW, Chang DT. Metabolic tumor volume predicts disease progression and survival in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:27-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee JW, Kang CM, Choi HJ, Lee WJ, Song SY, Lee JH, Lee JD. Prognostic Value of Metabolic Tumor Volume and Total Lesion Glycolysis on Preoperative ¹⁸F-FDG PET/CT in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:898-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ryu IS, Kim JS, Roh JL, Lee JH, Cho KJ, Choi SH, Nam SY, Kim SY. Prognostic value of preoperative metabolic tumor volume and total lesion glycolysis measured by 18F-FDG PET/CT in salivary gland carcinomas. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1032-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Meignan M, Cottereau AS, Versari A, Chartier L, Dupuis J, Boussetta S, Grassi I, Casasnovas RO, Haioun C, Tilly H, Tarantino V, Dubreuil J, Federico M, Salles G, Luminari S, Trotman J. Baseline Metabolic Tumor Volume Predicts Outcome in High-Tumor-Burden Follicular Lymphoma: A Pooled Analysis of Three Multicenter Studies. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3618-3626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | de Geus-Oei LF, van der Heijden HF, Corstens FH, Oyen WJ. Predictive and prognostic value of FDG-PET in nonsmall-cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Cancer. 2007;110:1654-1664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pan L, Gu P, Huang G, Xue H, Wu S. Prognostic significance of SUV on PET/CT in patients with esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1008-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sperti C, Pasquali C, Chierichetti F, Ferronato A, Decet G, Pedrazzoli S. 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in predicting survival of patients with pancreatic carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:953-959; discussion 959-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Diao W, Tian F, Jia Z. The prognostic value of SUVmax measuring on primary lesion and ALN by 18F-FDG PET or PET/CT in patients with breast cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2018;105:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mistrangelo M, Pelosi E, Bellò M, Ricardi U, Milanesi E, Cassoni P, Baccega M, Filippini C, Racca P, Lesca A, Munoz FH, Fora G, Skanjeti A, Cravero F, Morino M. Role of positron emission tomography-computed tomography in the management of anal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Whitman GJ. 1–15 Early Prediction of Response to Chemotherapy in Metastatic Breast Cancer Using Sequential 18F-FDG PET. Breast Diseases: A Year Book Quarterly. 2007;18:41-42. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Galt RH. The opiate anomalies--another possible explanation? J Pharm Pharmacol. 1977;29:711-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |