Published online Aug 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i16.3542

Peer-review started: May 27, 2020

First decision: June 15, 2020

Revised: June 26, 2020

Accepted: August 6, 2020

Article in press: August 6, 2020

Published online: August 26, 2020

Processing time: 90 Days and 9.6 Hours

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common bacterial infections. Acute pyelonephritis or upper urinary tract infection is often accompanied by bacteremia; however, bacteremia resolves in most cases without complication. Rarely, complications due to bacteremia occur. One of these is osteomyelitis. It mainly affects the lumbar vertebral bodies, and rarely affects other site.

An 80-year-old woman presented to the hospital with a two-month history of pain in both legs. Two months ago, she was admitted to the hospital for fever, flank pain, and urinary frequency and was diagnosed with bacteremic UTI. During hospitalization, she complained of pain in both legs; however, the pain resolved shortly after, and no abnormalities were observed on physical examination. Therefore, she was placed on 2-wk antibiotic therapy for UTI without further evaluation for leg pain. However, pain recurred after discharge and persisted; therefore, an imaging test was performed. Bone scan and magnetic resonance imaging suggested osseous infection in both femurs, tibiae and patellae. Surgical treatment was performed, and tissue- and bone cultures revealed Escherichia coli, a previously observed pathogen, which demonstrated same antibiotic sensitivities, as noted in previous UTI. She was diagnosed with disseminated osteomyelitis, as a complication of UTI, and was placed on an 8-wk antibiotic therapy.

Indication for osteomyelitis should be high regardless of bone pain at sites other than lumbar spine after or during UTI.

Core tip: Osteomyelitis caused by urinary tract infections rarely occurs, and most cases involve the lumbar vertebral bodies. The involvement of sites other than the lumbar vertebrae has only been reported in a few cases. This study presents a rare case of disseminated osteomyelitis (involving bilateral femur, knee and tibia) caused by urinary tract infection (UTI) in an immunocompetent patient. Escherichia coli was isolated from both surgically excised tissue and bone cultures, and demonstrated same antibiotic sensitivities, as observed in the previous UTI. This case highlights that osteomyelitis after UTI can occur at sites other than the lumbar spine.

- Citation: Kim YJ, Lee JH. Disseminated osteomyelitis after urinary tract infection in immunocompetent adult: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(16): 3542-3547

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i16/3542.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i16.3542

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common bacterial infections, and it is often accompanied by bacteremia. Nevertheless, metastatic infection or complication due to bacteremic UTI is rare[1]. Rarely, osteomyelitis can occur in the context of a UTI[2]. Most cases involve lumbar vertebral bodies; there are only a few reports involving the non-vertebral bones in the literature. Only one case reported of multifocal osteomyelitis, including both femur and tibia in a renal allograft patient after urosepsis[3]. We present the first case of both femur and tibia osteomyelitis after UTI caused by Escherichia coli (E. coli) in a previously healthy patient.

An 80-year-old woman presented to the hospital with a two-month history of pain in both legs.

Two months ago, pain initially manifested in both legs during hospitalization for UTI. The pain was vague, heavy and diffuse, ranging from the knee to the pelvis. Because the pain shortly resolved and no abnormalities were observed on physical examination, no further evaluation was performed for the leg pain. She was placed on a 2-wk antibiotic therapy for UTI. Subsequently, she was discharged and the antibiotic was discontinued because of improvements in clinical symptoms (to normal), as demonstrated by laboratory examinations. However, after discharge, the pain recurred and worsened over time.

The patient had a 10-mo history of hypertension with medication.

On admission, the patient’s vital signs were within normal range. She complained of diffuse tenderness in both lower extremities, without definite erythema, warmth, or edema. Muscular strength in both legs was normal, and there were no limitations of movement.

Complete blood count revealed normal white blood cell count (WBC), with a neutrophil percentage slightly elevated at 73.4%. Serum C-reactive protein levels significantly increased to 112.82 mg/L (normal range 0-5 mg/L) and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 33 mm/h. Other biochemistries and urinalysis were normal. Knee joint aspiration revealed WBC of 24000/μL [PMN (polymorphonucleocytes) 90%] and RBC of 100/μL.

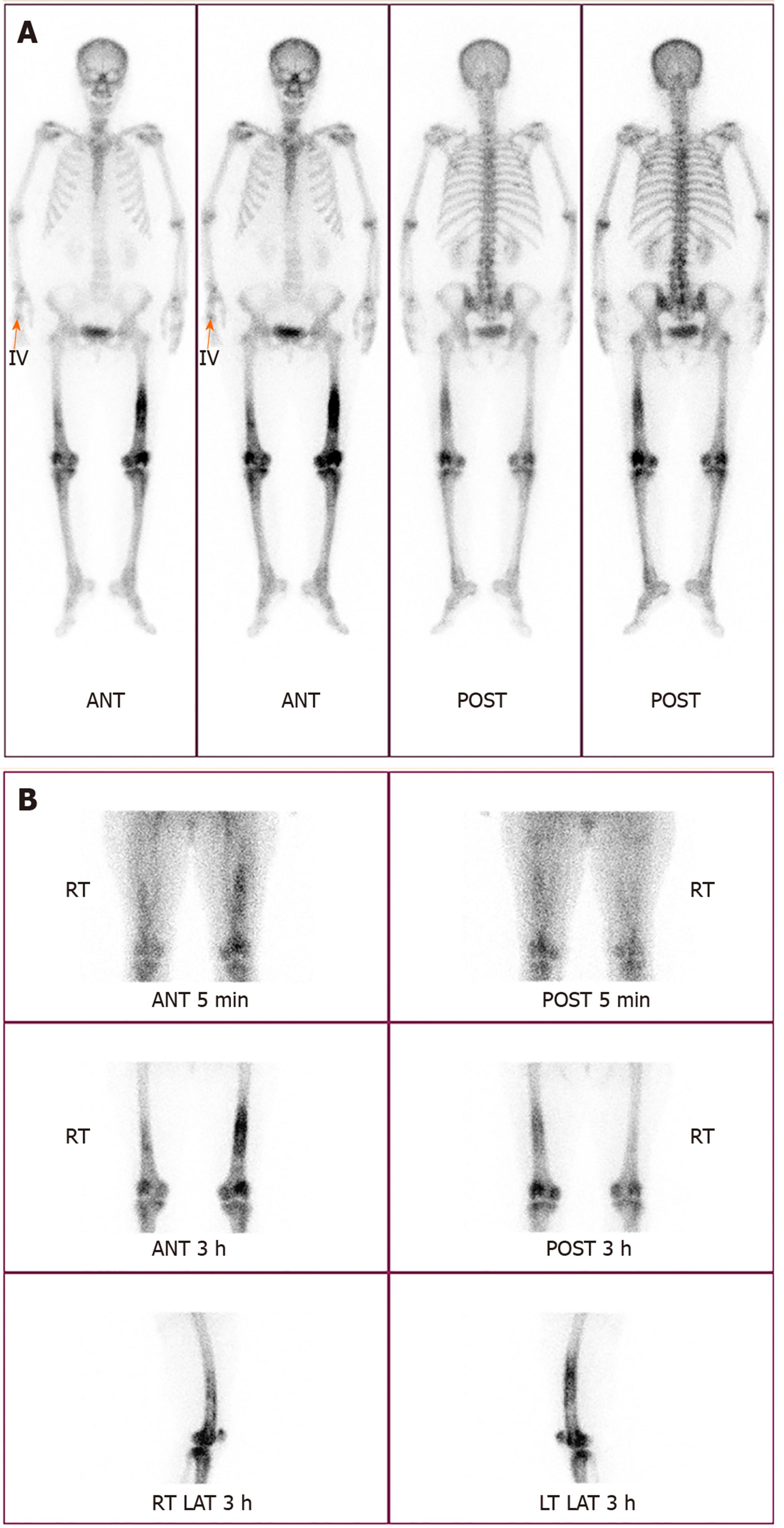

Physical examination revealed no prominent local inflammation; however the pain did not resolve continuously. So, bone scan was performed, and revealing diffuse increased uptake in the shaft of both femurs (more severe in the left than the right) and the periarticular bones of both knee joints (Figure 1). Because these findings can be equally observed in the context of tumors and osseous infections, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed.

Large intramedullary lesions with diffuse irregular contours were observed in both mid- to distal femurs, both proximal tibiae, and both patellae. Multiple T2 high and T1 low SI fluid collections with peripheral thick enhancement were observed, extending from diaphysis to epiphysis. Diffuse enhancement of surrounding soft tissue was observed along the periosteum with focal cortical disruption in the medial portion of the supra-condyle of the right femur (Figure 2).

An imaging test suspected osseous infection and involvement of the knee joint, we performed joint aspiration and cultures. The joint fluid analysis revealed WBC of 24000/μL (PMN 90%), RBC of 100/μL, and culture-negative. Considering the MRI findings, the possibility of osseous infection was high. Exclusion of bone tumor through histopathological examination was necessary for the following reasons: (1) The involvement of bones other than the lumbar vertebrae is rare in adult osteomyelitis caused by the hematogenous spread of infection; and (2) Increased uptake on bone scan can similarly be observed in bone tumor.

Surgical drainage and biopsy were performed. Gross examination revealed grey colored pus-like discharge and inflammatory tissue in the femoral medulla, and periosteal reactions were observed in the cortex. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL)-producing E. coli was observed in tissue- and bone cultures. This bacterium was the previously observed pathogen, which demonstrated same antibiotic sensitivities, as observed in the previous UTI. Similarly, pathological findings indicated acute osteomyelitis.

The final diagnosis of this case was bilateral femur, knee, and tibia osteomyelitis due to UTI caused by ESBL-producing E. coli.

Initially, the patient was exclusively treated with intravenous antibiotics (meropenem, 1 g every 8 h for 4 wk); however, clinical symptoms and inflammatory markers did not improve. Medical treatment failure had to be differentiated from bone tumor, and surgery was performed. Incision and drainage, antibiotics bead insertion was performed because the surgical findings indicated osseous infection. We did not perform extensive debridement. Because the lesions were extremely wide, and if all the lesions were removed, the patient would be disabled. Following surgical drainage, she was placed on long-term antibiotic therapy (meropenem, 1 g every 8 h for 8 wk).

After the completion of intravenous antibiotic therapy, symptoms and inflammatory markers improved to normal. At a follow-up visit 1 year after surgery, the patient was asymptomatic. Bone scan revealed complete remission of the multifocal increased uptake.

Osteomyelitis is a bone infection that can be associated with severe sequelae if not diagnosed early and treated properly. Osteomyelitis can be classified into hematogenous and non-hematogenous (contagious and by direct inoculation), based on the route of entry. Hematogenous osteomyelitis accounts for approximately 20% of adult osteomyelitis; the most common site of infection is vertebrae in adults and femur and tibia in children[4]. Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus are the most common causative agents. Osteomyelitis caused by gram-negative bacilli is rare; most cases of contagious spread occur in the context of predisposing factors, such as open fracture, vascular insufficiency, prothesis, immunosuppression, or underlying joint disease[5,6]. Very rarely, gram-negative vertebral osteomyelitis of hematogenous origin has been reported in the elderly[7]. A common port of entry is the urinary tract[8]. Osteomyelitis secondary to UTI in adults usually involves the lumbar vertebrae, although there are a few rare cases of other involved bones (cervical spine, sternum, and ribs, among others)[2,5,9]. Only one case have been reported in a patient who developed both femur and tibia osteomyelitis due to UTI, and this patient was a renal allograft recipient[3]. There have been no reports of bilateral femur, knee and tibia osteomyelitis caused by hematogenous infection in an immunocompetent patient.

Multifocal uptake in bone scan can be observed not only in osseous infection but also in bone tumors, such as osteosarcoma and osteochondroma. Therefore, in this case, additional imaging (MRI) and histological confirmation were performed. The surgical and pathological findings indicate acute osteomyelitis. E. coli was observed in tissue and bone cultures.

In addition to UTIs, infections of the biliary tract, gastrointestinal tract and female genital tract can similarly be possible sources of E. coli osteomyelitis. Nevertheless, the organism cultured from her bones appeared to be identical to that which caused the previous bacteremic UTI. No other possible focus was observed. Possibly, bacteria seeded her bones during the previous hospitalization for UTI. Two weeks of antibiotic therapy is sufficient for the treatment of simple bacteremia and UTIs; however, it is insufficient to eradicate the foci of bone infection. Her symptoms may have improved transiently in response to antibiotic treatment and recurred after the termination of antibiotics.

There are several classification systems used for osteomyelitis. Among them, the Cierny-Mader staging system (Table 1) is the most clinically relevant. This system stratifies hosts into three categories (A-C) based on physiologic comorbidities and designates four anatomic stages of infection that are combined to produce 12 classifications[4,10]. Generally, treatment of osteomyelitis should be accompanied by surgical drainage alongside antibiotic treatment; however, in the case of hematogenous spread of osteomyelitis, surgical treatment is generally unnecessary[11].

| Anatomic type | Physiologic class |

| Stage 1: Medullary osteomyelitis | A Host: Normal host |

| Stage 2: Superficial osteomyelitis | B Host: Systemic compromise (Bs) |

| Stage 3: Localized osteomyelitis | Local compromise (Bl) |

| Stage 4: Diffuse osteomyelitis | Systemic and local compromise (Bls) |

| C Host: Treatment worse than the disease | |

| Systemic or local factors that affect immune surveillance, metabolism and local vascularity | |

| Systemic (Bs) | Local (Bl) |

| Malnutrition | Chronic lymphedema |

| Renal, hepatic failure | Venous stasis |

| Diabetes mellitus | Major vessel compromise |

| Chronic hypoxia | Arteritis |

| Immune disease | Extensive scarring |

| Malignancy | Radiation fibrosis |

| Extremes of age | Small vessel disease |

| Immunosuppression or neuropathy | Complete loss of sensation |

| Immune deficiency | Tobacco abuse |

Because of the patient’s poor response to antibiotic treatment alone, her anatomical stage was type IV, and we were obliged to exclude bone tumor. For these reasons, surgery was performed along with antibiotic treatment. She was successfully treated with surgical drainage and eight weeks of long-term antibiotic treatment.

As the number of elderly patients continues to increase, complications of UTI are equally increasing. Nevertheless, osteomyelitis due to UTI is rare, and infection of bones other than the lumbar vertebrae remains rare. We reported the first case of bilateral femur, knee and tibia E. coli osteomyelitis secondary to a UTI in an immunocompetent adult. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment is important for prognosis. Because of vague symptoms and unspecific findings, diagnosis can be delayed more than three months in up to 50% of vertebral osteomyelitis cases[12]. The index of suspicion for osteomyelitis should be high even if there is bone pain at sites other than lumbar spine after or during a UTI.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ferreira GSA, Monti M, Thanindratarn P S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Nicolle LE. Urinary tract infection. Crit Care Clin. 2013;29:699-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sierra MA, Luparello FJ, Lewin JR. Vertebral osteomyelitis and urinary-tract infection. Arch Intern Med. 1961;108:128-131. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Valson AT, David VG, Balaji V, John GT. Multifocal bacterial osteomyelitis in a renal allograft recipient following urosepsis. Indian J Nephrol. 2014;24:189-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Calhoun JH, Manring MM. Adult osteomyelitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19:765-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Matsuura H, Sue M, Takahara M, Kuninaga N. Escherichia coli rib osteomyelitis. QJM. 2019;112:35-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Carvalho VC, Oliveira PR, Dal-Paz K, Paula AP, Félix Cda S, Lima AL. Gram-negative osteomyelitis: clinical and microbiological profile. Braz J Infect Dis. 2012;16:63-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Herfort A. Osteomyelitis of the lumbar vertebrae due to Escherichia coli; complication of acute suppurative pneumonia. J Am Med Assoc. 1952;150:1073-1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chew LC. Septic monoarthritis and osteomyelitis in an elderly man following Klebsiella pneumoniae genitourinary infection: case report. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35:100-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hamzaoui A, Salem R, Koubaa M, Zrig M, Mnif H, Abid A, Golli M, Mahjoub S. Escherichia coli osteomyelitis of the ischium in an adult. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95:636-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sanders J, Mauffrey C. Long bone osteomyelitis in adults: fundamental concepts and current techniques. Orthopedics. 2013;36:368-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004;364:369-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1313] [Cited by in RCA: 1364] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sapico FL, Montgomerie JZ. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: report of nine cases and review of the literature. Rev Infect Dis. 1979;1:754-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |