Published online May 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i10.2023

Peer-review started: January 27, 2020

First decision: March 5, 2020

Revised: March 25, 2020

Accepted: April 24, 2020

Article in press: April 24, 2020

Published online: May 26, 2020

Processing time: 119 Days and 6.8 Hours

The management of recurrent gallstone ileus (GSI) is unsatisfactory, and there is no consensus on how to reduce the incidence of recurrent GSI.

A 79-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department of our hospital complaining of abdominal pain. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed cholecystolithiasis, intrahepatic bile duct dilatation, gas accumulation, small intestinal obstruction, and circular high-density shadow in the intestinal cavity. Emergency surgery revealed that the small intestine had extensive adhesions, unclear gallbladder exposure, obvious adhesions, and difficult separation. The obstruction was located 70 cm between the ileum and the ileocecum, which was incarcerated by gallstones, and a simple enterolithotomy was carried out. On the third day after the operation, he had passed gas and defecated and had begun a liquid diet. On the fifth day after the operation, he suddenly experienced abdominal distension and discomfort. Emergency CT examination revealed recurrent GSI, and the diameter of the stone was approximately 2.0 cm (consistent with the shape of cholecystolithiasis on the abdominal CT scan before the first operation). The patient’s symptoms were not significantly relieved after conservative treatment. On the ninth day after the operation, emergency enterolithotomy was performed again along the original surgical incision. On the twentieth day after the second operation, the patient fully recovered and was discharged from the hospital.

We believe that a thorough examination of the bowel and gallbladder for gallstones based on preoperative imaging during surgery and removal of them as far as possible on the premise of ensuring the safety of patients are an effective strategy to reduce the recurrence of GSI.

Core tip: There is no consensus on how to effectively reduce the recurrence rate of recurrent gallstone ileus (GSI). Herein, we present a rare case of recurrent GSI, in order to elucidate and review the pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, and consensus recommendations regarding the management of recurrent GSI. This case highlights the importance of a detailed abdominal physical examination and imaging data interpretation before the operation, as well as a systematic and careful search for the existence of other residual stones during the operation on the premise of ensuring safety. Enterolithotomy combined with cholecystectomy or gallbladder lithotomy is an effective strategy for reducing the recurrence of GSI.

- Citation: Jiang H, Jin C, Mo JG, Wang LZ, Ma L, Wang KP. Rare recurrent gallstone ileus: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(10): 2023-2027

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i10/2023.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i10.2023

Gallstone ileus (GSI) is a rare complication of cholecystolithiasis that occurs in 0.15%–1.5% of cholelithiasis cases[1]. It has been recognized that early diagnosis of GSI can be made by combining clinical symptoms (epigastralgia with nausea and vomiting) with abdominal computed tomography (CT) findings of Rigler’s triad (ectopic gallstone, bowel obstruction, and pneumobilia)[2]. However, patients often are in a critical condition, have complications due to other medical diseases, and cannot tolerate long-term surgery. Therefore, the management of GSI is still unsatisfactory.

Overall, the operative managements of GSI can be classified into two categories: Enterolithotomy, cholecystectomy, and fistula repair (single-stage surgery); and simple enterolithotomy (the most frequently reported surgical procedure)[3]. Despite the lack of consensus, the vast majority of surgeons believe that enterolithotomy alone or enterolithotomy followed by a delayed two-stage treatment approach is the preferred choice, offering a low mortality rate but a high risk of recurrence[4,5].

In general, the recurrence rate of GSI is approximately 5%-8%[1], and there is no consensus on how to reduce the incidence of recurrent GSI. To highlight this, we report an interesting case of recurrent GSI, in order to elucidate and review the pathogenesis, presentation, diagnosis, and consensus recommendations regarding the management of recurrent GSI.

A 79-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department of our hospital complaining of right upper abdominal pain.

The patient’s symptoms started 3 d ago and had been aggravated by abdominal distension during the last 24 h.

The patient underwent epididymal tuberculosis surgery 40 years ago, had of history of hypertension for 10 years, underwent colon cancer surgery 9 years ago, and developed cholecystolithiasis with chronic cholecystitis 3 mo ago.

The patient’s temperature was 36.9 °C, heart rate was 68 bpm, respiratory rate was 18 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 113/69 mmHg, and oxygen saturation in room-temperature air was 98%; the patient had abdominal distension, whole abdominal tenderness, and no rebound pain. The frequency of bowel sounds was once per minute, and there were no other pathological signs. Based on these findings, acute intestinal obstruction or cholecystolithiasis with acute cholecystitis was considered.

Blood analysis showed significant leukocytosis (19.1 × 109/L), with a predominant number of neutrophils (92.1%) and a normal haematocrit level and platelet count. The prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times were normal, and serum C-reactive protein was increased to 48.1 mg/L (normal range < 10.0 mg/L). The blood biochemistry and urine analyses were normal. Electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, and arterial blood gas results were also normal.

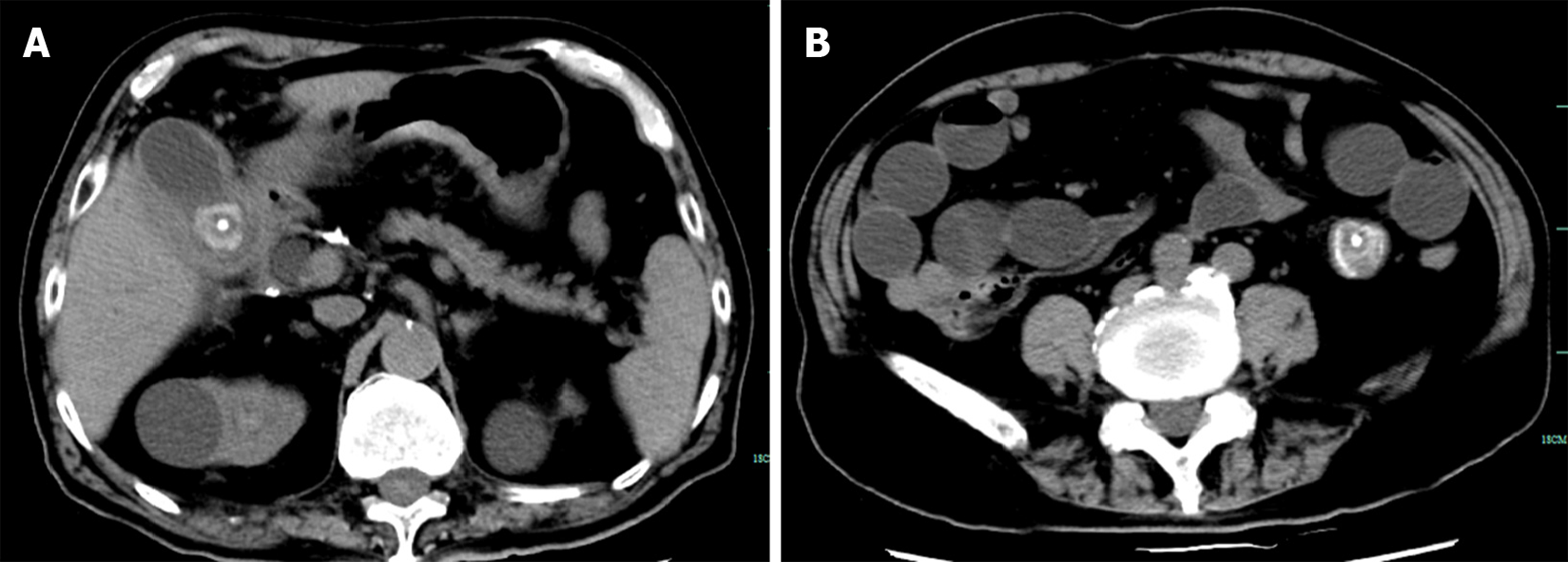

An initial imaging evaluation by abdominal CT scanning revealed cholecystolithiasis (approximately 2.6 cm in diameter) (Figure 1A), intrahepatic bile duct dilatation, gas accumulation, small intestinal obstruction, and circular high-density shadow in the intestinal cavity (approximately 3.5 cm in diameter) (Figure 1B).

The final diagnosis of the presented case was gallstone ileus.

Based on CT findings and the patient’s symptoms, emergency surgical treatment was decided considering that the gallstone intestinal obstruction could not be relieved by itself. Laparoscopic exploration during the operation revealed that the small intestine had extensive adhesions, unclear gallbladder exposure, obvious adhesions, and difficult separation, so conversion to laparotomy occurred. It was found that the obstruction was located 70 cm between the ileum and the ileocecum, which was incarcerated by gallstones, and a decision was made to carry out simple enterolithotomy; the stone diameter was approximately 3.5 cm. After the operation, the patient was given symptomatic support treatment, such as fasting, fluid replacement, anti-infection agents, pain relief, and stomach protection.

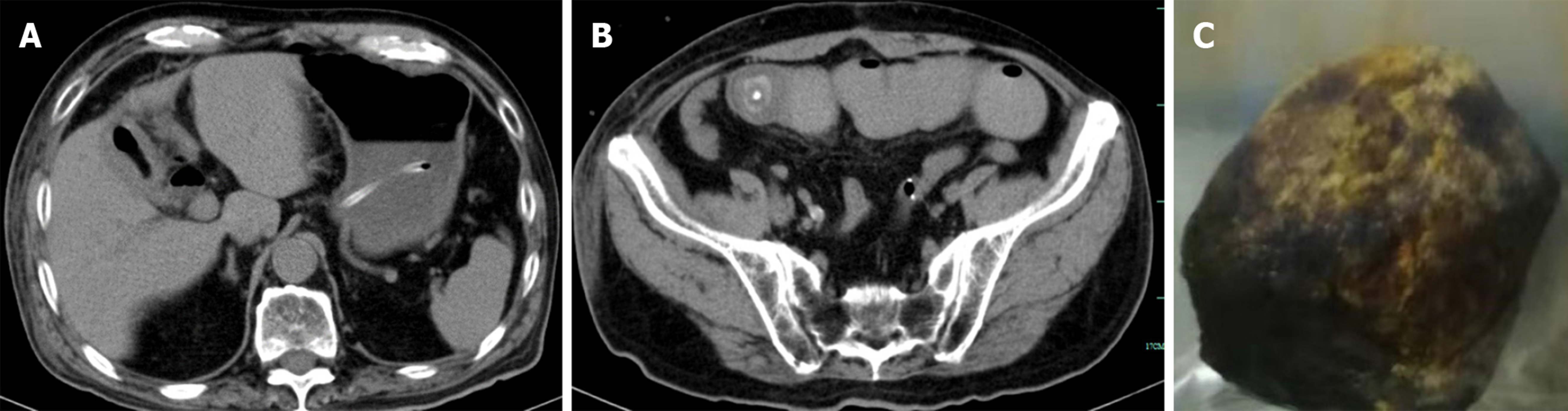

On the third day after the operation, the patient had passed gas and defecated and had begun a liquid diet. On the fifth day after the operation, he suddenly experienced abdominal distension and discomfort. Emergency CT examination revealed GSI. It was also revealed that cholecystolithiasis had disappeared according to the abdominal CT scan taken before the operation (Figure 2A), and that the diameter of the stone in the bowel was approximately 2.0 cm, which is consistent with the shape of cholecystolithiasis in Figure 1A (Figure 2B). Considering that the stone was less than 2.5 cm in diameter, it was possible that it could be expelled on its own. Given the fact that the patient had no obvious abdominal pain, he was given conservative treatment, such as fasting, gastrointestinal decompression, and edible oil moistening intestine, but the patient’s symptoms were not significantly relieved. Re-examination of abdominal CT on the seventh and ninth days after the operation showed that the location of the stones did not move significantly. Considering that the possibility of the spontaneous excretion of stones was small, on the ninth day after the first operation, laparotomy was performed along the original surgical incision, the stone was located in the place where the intestine was sutured during the first enterolithotomy, and the diameter of the stone was close to 3 cm (Figure 2C). However, the clinical conditions are not allowed to perform careful surgical exploration (the patient was elderly with severe adhesion of the right upper abdomen and unclear exposure of the gallbladder and duodenum), therefore, the site of bilioenteric fistula was not found. On the twentieth day after the second operation, the patient fully recovered and was discharged from the hospital.

The incidence of recurrent GSI is between 2% and 5%. Approximately 57% of recurrence cases occur within 6 mo of initial surgery[6]. While the mortality rate of GSI is 12%-20%[3], it is generally believed that if the diameter of cholecystolithiasis is less than 2.0 cm, GSI can generally be relieved on its own[7]. When the diameter of cholecystolithiasis is greater than 2.5 cm, surgery is the most frequently adopted and the most effective treatment in such cases.

Enterolithotomy alone or enterolithotomy followed by delayed two-stage treatment seems to be the first choice, because of its lower mortality rate and lower risk of recurrence[4,5,8]. Reisner et al[9] revealed that a single-stage procedure had a higher mortality rate of 16.9% compared to the rate of 11.7% with simple enterolithotomy (P < 0.17). Moreover, the recurrence rates from retained stones missed during initial surgery or the formation of new gallstones were the same in both groups[9]. Gallstones pass into the bowel and are cleared in 80%-90% of cases[10]. The most frequent sites of communication are cholecystoduodenal region (69%-70%), cholecystocolonic region (14%), and the small intestine (6%)[10]. Based on these three situations, Koichi holds a new point of view[5]. For patients with duodenal incarceration, one-stage surgery is considered to be the first choice. For patients with intestinal incarceration, a two-stage operation is recommended, and for patients with colonic incarceration, a one-stage operation is recommended.

In the present case, laparoscopic exploration revealed that the small intestine had extensive adhesions, unclear gallbladder exposure, obvious adhesions, and difficult separation. In addition, the patient was in a critical condition, and one-stage cholecystectomy prolonged the operation time and increased the risk of operation. Although cholecystolithiasis remained during the operation and the choledochojejunal fistula was not closed, the choledochojejunal fistula may have closed spontaneously, and GSI usually does not recur within 2 mo[1], so cholecystectomy was not performed. Only on the fifth day after the operation did the patient experience GSI recurrence, and CT showed that the faecal stone causing the small intestinal obstruction was the residual gallstone that had not been treated during the first operation. Although it has been previously reported that GSI recurrence usually occurs within 6 mo after operation[11], and the fastest recorded time has been within 2 mo[4], there have never been reports of GSI recurrence in such a short time.

Cholecystectomy is the most effective method for preventing recurrent GSI[1]. Although CT improves the diagnostic rate of GSI, some instances of non-calcified cholecystolithiasis may be missed before the operation; hence, laparotomy should involve a systematic and meticulous search for the presence of further enteric stones[12]. The discovery of faceted stones during operations also often indicates the possibility of recurrent GSI. A thorough palpation of the entire bowel must be undertaken during laparotomy to avoid the possibility of further undetected gallstones, which may lead to recurrent GSI in the future[6]. Small cholecystolithiasis is also a risk factor for recurrent GSI. If cholecystectomy cannot be performed, cholecystectomy for stone extraction is also an option for reducing recurrence[13].

We believe that a thorough examination of the bowel and gallbladder for gallstones based on preoperative imaging during surgery and removal of them as far as possible on the premise of ensuring the safety of patients is an effective strategy to reduce the recurrence of GSI.

We are very grateful to our colleagues from the Department of Imaging for providing the computed tomography pictures.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gupta R, Fogli L S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Rabie MA, Sokker A. Cholecystolithotomy, a new approach to reduce recurrent gallstone ileus. Acute Med Surg. 2019;6:95-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sahsamanis G, Maltezos K, Dimas P, Tassos A, Mouchasiris C. Bowel obstruction and perforation due to a large gallstone. A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;26:193-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lamba HK, Shi Y, Prabhu A. Gallstone ileus associated with impaction at Meckel's diverticulum: Case report and literature review. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8:755-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Halabi WJ, Kang CY, Ketana N, Lafaro KJ, Nguyen VQ, Stamos MJ, Imagawa DK, Demirjian AN. Surgery for gallstone ileus: a nationwide comparison of trends and outcomes. Ann Surg. 2014;259:329-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Inukai K. Gallstone ileus: a review. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019;6:e000344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gandamihardja TA, Kibria SM. Recurrent gallstone ileus: beware of the faceted stone. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Aslam J, Patel P, Odogwu S. A case of recurrent gallstone ileus: the fate of the residual gallstone remains unknown. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Freeman MH, Mullen MG, Friel CM. The Progression of Cholelithiasis to Gallstone Ileus: Do Large Gallstones Warrant Surgery? J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1278-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Reisner RM, Cohen JR. Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases. Am Surg. 1994;60:441-446. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Apollos JR, Guest RV. Recurrent gallstone ileus due to a residual gallstone: A case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;13:12-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dai XZ, Li GQ, Zhang F, Wang XH, Zhang CY. Gallstone ileus: case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5586-5589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 12. | Wang L, Dong P, Zhang Y, Tian B. Gallstone ileus displaying the typical Rigler triad and an occult second ectopic stone: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e8541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Osagiede O, Pacurari P, Colibaseanu D, Jrebi N. Unusual Presentation of Recurrent Gallstone Ileus: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2019;2019:8907068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |