Published online May 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i10.2016

Peer-review started: January 10, 2020

First decision: March 18, 2020

Revised: March 26, 2020

Accepted: April 15, 2020

Article in press: April 15, 2020

Published online: May 26, 2020

Processing time: 136 Days and 8.2 Hours

Liver infarction is a rare necrotic lesion due to the dual blood supply consisting of the hepatic artery and portal vein. The absence of specific clinical manifestations and imaging appearances usually leads to misdiagnosis and poor prognosis. Thus, the precise diagnosis of liver infarction always requires imaging studies, serum studies, and possible liver biopsy.

We report a case of 31-year-old man who developed a huge liver infarction. Persistent right upper abdominal pain and intermittent fever were the main symptoms in this patient. Computed tomography revealed a huge irregular lesion with a maximum diameter of 12.7 cm in the right lobe of the liver. Three-dimensional reconstruction was performed and no significant interruption of the main hepatic vessels was observed. The lesion was initially considered to be a malignant tumor with internal bleeding. Laparoscopic right hepatectomy was performed, and pathology indicated a rare liver infarction. The patient recovered well and was discharged on postoperative day 21. No fever or abnormal liver function were reported in the subsequent 6 mo.

In patients with a huge liver infarction, early surgical intervention may be beneficial.

Core tip: We report a case of liver infarction that was initially considered to be a tumor with bleeding based on computed tomography. Liver infarction is caused by the obstruction of hepatic vessels, and a huge liver infarction is very rare due to the dual hepatic blood supply. The clinical manifestations and imaging appearances of liver infarction are nonspecific. The precise diagnosis always requires multiple imaging methods, serum studies, and pathological examination. In addition to conservative treatment, early surgical intervention is beneficial in patients with a huge liver infarction. This case report provides a valuable reference for the diagnosis and treatment of this disease.

- Citation: Wang FH, Yang NN, Liu F, Tian H. Unexplained huge liver infarction presenting as a tumor with bleeding: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(10): 2016-2022

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i10/2016.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i10.2016

Primary liver cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors, and ranks third with respect to tumor mortality worldwide. The incidence of primary liver cancer is much higher in China due to hepatitis B infection[1]. The precise diagnosis of liver lesions is helpful for the application of targeted therapeutic options and a good prognosis, while misdiagnosis is sometimes inevitable due to the similar imaging appearances of liver cancer and other benign lesions. We describe a patient with a huge liver infarction and bleeding that was initially considered to be liver cancer with bleeding. A review of the literature on liver infarction was also performed.

A 31-year-old man was admitted with persistent right upper abdominal pain, fever, and anorexia for 6 d.

He was healthy without a history of personal or family tumors. Abdominal ultrasound revealed fatty liver and mixed echoes in the right lobe of the liver, and a non-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen also suggested a huge lesion in the right lobe of the liver with mixed density. Antibiotics had been administered in a local hospital to help relieve the patient’s symptoms.

Upon admission, his intermittent fever peaked at 38.5 °C without symptoms of respiratory infection. Percussion pain in the liver area was detected with no other abnormalities upon physical examination.

Laboratory studies excluded hepatitis B and C infection, but showed leukocytosis, neutrophilia, elevated aspartate aminotransferase at 76 U/L, and alanine transaminase at 477.4 U/L. The triglyceride, total cholesterol, carcinoembryonic antigen, alpha-fetoprotein, and carbohydrate antigen-199 levels were in the normal range.

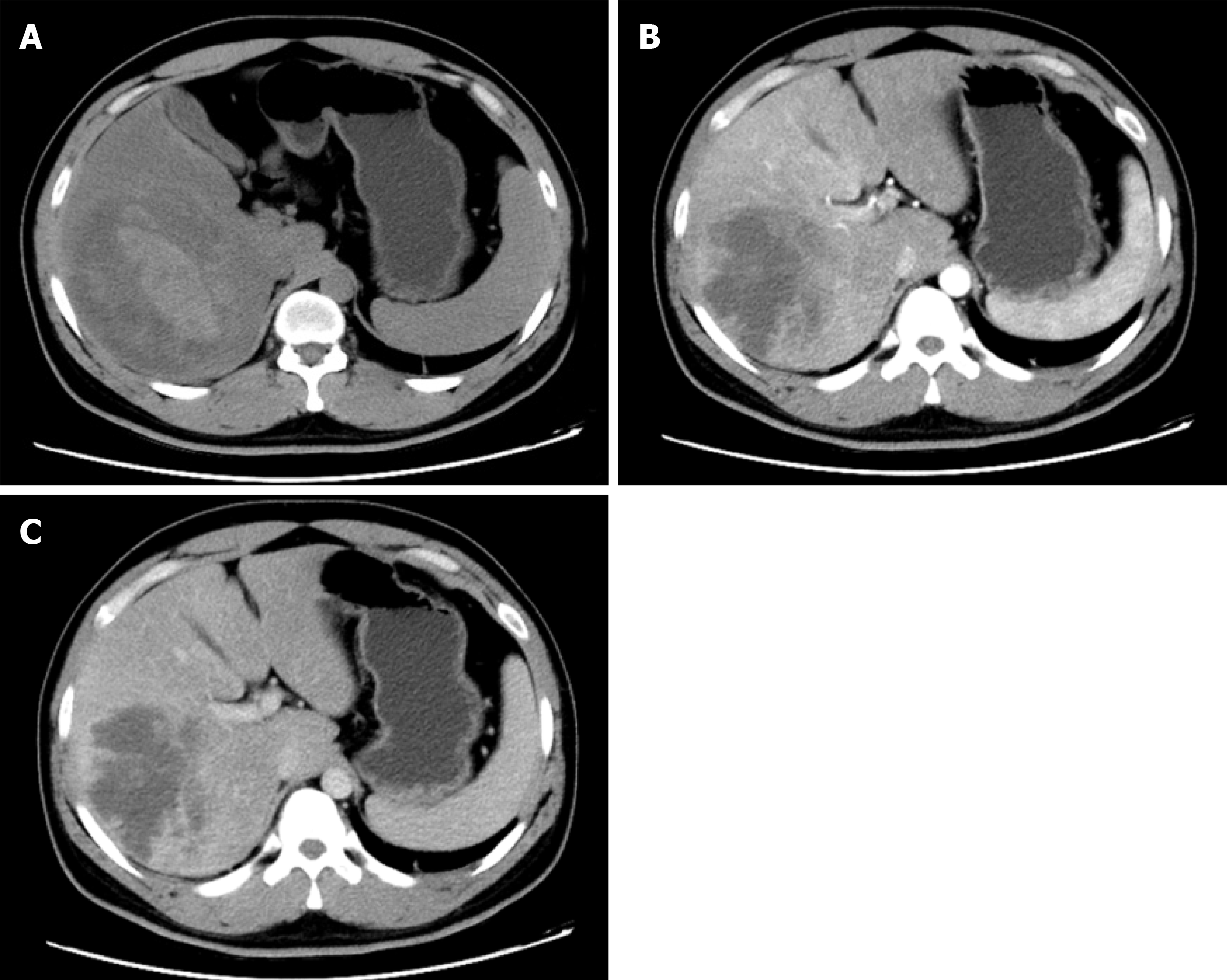

An enhanced CT scan indicated fatty liver, and a huge irregular lesion with a maximum diameter of 12.7 cm was observed in the right lobe of the liver. On non-enhanced CT, a slightly high density was also found in the lesion (Figure 1A), which was consistent with previous CT images. The entire tumor was not enhanced, and the peripheral tissues were delayed enhanced (Figure 1B and D). The typical CT image of hepatocellular carcinoma was enhanced at the early stage and with peripheral vascular contrast enhancement. However, for some unusual hepatic tumors, the image feature was delayed enhanced, such as liver metastasis from gastric cancer. The imaging findings suggested a malignant liver tumor with bleeding. Three-dimensional reconstruction was performed to identify the relationship between the lesion and adjacent hepatic vessels. No significant interruption of the main liver artery and portal vein was observed (Figure 2A-C).

The surgical specimen showed a huge necrotic lesion, and multiple adipose lesions were also observed (Figure 3A). Pathological examination indicated a rare liver infarction (Figure 3B-D).

The antibiotics ceftriaxone sodium and levofloxacin, as well as hepatoprotective drugs, were administered to control the fever and improve liver function.

On the 9th day after admission, the patient underwent laparoscopic right hepatectomy. He recovered well following treatment with antibiotics, nutritional support, and human albumin, and was discharged on postoperative day 21. No fever or abnormal liver function were subsequently reported.

Liver infarction is a type of hepatic necrosis caused by the obstruction of vessels, which is rare due to the hepatic dual blood supply, the tolerance of hepatocytes to low oxygen, and the immediate opening of collateral vessels within the liver[2,3]. Simultaneous occlusion of the hepatic artery and portal vein is sometimes considered to be essential in a huge liver infarction[4]; however, the abrupt truncation of a single hepatic artery can also lead to severe liver infarction and even death[5]. Liver infarction is usually reported at autopsy. Seeley et al[6] investigated 19 autopsies of patients with hepatic infarcts, and found that ten autopsies showed arterial occlusion, four showed only portal vein thrombosis, and no vascular occlusion was found in the other five patients. In our case, we found no obvious hepatic vessel lesions on the CT scan and three-dimensional reconstruction of the liver. In a subsequent study, Saegusa et al[7] reported 20 cases of hepatic infarction and 17 had circulatory failure. Furthermore, 15 had portal vein thrombosis, which indicated the importance of portal vein disturbance in the development of liver infarction. Based on these reports, simultaneous or single occlusion of the hepatic artery and portal vein appears to be the anatomical basis of hepatic infarction.

The early diagnosis of liver infarction is difficult due to its rarity and absence of typical symptoms. It can initially present as chest or right upper abdominal pain, fever, or with associated nausea and vomiting[8-10]. In addition, related laboratory studies for hematological and biochemical markers are not specific, which makes the diagnosis challenging[11,12]. In our report, the patient had right upper abdominal pain and fever, and related serum tests showed leukocytosis, neutrophilia, and elevated aspartate aminotransferase and alanine transaminase, but it is difficult to differentiate between liver abscess or a tumor with bleeding or infection. Thus, a CT scan was performed, which indicated the areas of liver infarction with low attenuation that were circumscribed and wedge-shaped, and extended to the periphery of the liver[11]. The CT images in our patient showed an irregular lesion with an inside of slightly high density, which was considered to be bleeding. It was reported that gadophrin-2 displayed a persistent necrosis-specific contrast enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging, and was considered useful for diagnosis in a rat model of reperfused liver infarction[13]. Hepatobiliary scintigraphy is also considered to be a sensitive method for detecting early hepatic infarction even before ultrasonographic changes occur, which is helpful in improving prognosis[14].

The causes of liver infarction are diverse, although primary lesions in hepatic vessels are rare. It has been suggested that liver infarction may be secondary to circulatory shock, sepsis, anesthesia, or biliary disease[8,10]. We reviewed the literature on liver infarction (Table 1) and concluded that the common causes of this disorder are as follows: (1) Iatrogenic injury of hepatic vessels, mainly the hepatic artery. In normal liver, approximately 75% of the blood supply is from the portal vein, and 25% is from the hepatic artery. An anatomical abnormality of the hepatic artery is frequently observed, such as the right hepatic artery that can be derived from the proper or common hepatic artery or superior mesenteric artery. Wong et al[15] reported liver infarction due to injury to the right hepatic artery and portal vein during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgeons should avoid hepatic vessel injuries during gallbladder, bile duct, liver, and pancreas surgery. (2) Systemic diseases: Churg-Strauss syndrome is characterized by granulomatous vasculitis of multiple organ systems, which can lead to irregular narrowing of hepatic arteries and even liver infarction[3]. In pregnant or postpartum woman, antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are also considered causes of liver infarction due to multiple thromboses in vivo[11,16,17]. Related serum studies on anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-double-stranded DNA, anti-cardiolipin antibodies, and lupus anti-coagulant are useful for the diagnosis of APS and SLE[18]. In the present report, the above markers were investigated and found to be in the normal range. A hypercoagulable state, such as disseminated intravascular coagulation caused by severe postpartum hemorrhage, can induce thrombosis formation in hepatic vessels, hepatic infarction, and even acute hepatic failure[19,20]. (3) Treatment of liver diseases includes transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). TIPS is performed for the treatment of variceal bleeding and refractory ascites in patients with portal hypertension[21], while TACE is used for the treatment of liver cancer, liver bleeding, or for diagnostic purposes[22]. TIPS can induce hepatic hypoperfusion in the portal vein, while TACE interrupts liver artery blood flow. Therefore, the risk of liver infarction due to TACE is increased by TIPS[9,23]. Before TACE or TIPS is undertaken, it is important to evaluate the condition of the hepatic artery and portal vein for a better prognosis. And (4) Other causes: Ashida et al[2] reported a case of liver infarction due to liver abscess, without the occlusion of hepatic vessels. In our case, liver infarction was not due to the above three common causes; however, the patient had fatty liver and severe fatty degeneration of hepatocytes. Whether this was the origin of liver infarction requires further investigation.

| Ref. | Case | Symptoms | Serum study | Computed tomography | Liver vessels | Main treatments |

| Otani et al[3], 2003 | A 59-year-old man with Churg-Strauss syndrome | Cold and pain of fingers and toes | Hypereosinophilia, elevated IgE and transaminase | Low density at the periphery of the right lobe | Irregular narrowing of hepatic arteries | Surgery, intravenous PGE1, prednisolone |

| Khong et al[11], 2005 | A 30-year-old postpartum woman with DVT history | Right-sided chest pain, mild pyrexia | Leukocytosis, neutrophilia, elevated ALT | Multiple peripheral liver infarcts | - | Antibiotics, heparin and warfarin |

| Mayan et al[9], 2001 | A 66-year-old male with TIPS | Fever and shock, tenderness of right upper quadrant | DIC, AST and ALT increased | Wedge-shaped hypodense lesion of liver | No sign of portal vein occlusion or arterio-stent shunt | Amikacin, vancomycin, ceftriaxone |

| Park et al[23], 2016 | A 61-year-old woman with TACE | Epigastric pain, abdominal pain and distention | Elevations of AST and ALT | Nonenhancement and expansion of left hepatic lobe with DEE TACE | Middle hepatic vein to left portal vein shunt | Supportive care |

| Wong et al[15], 2001 | A 66-year-old woman with laparoscopic cholecystectomy | Fever, right upper quadrant pain | Leukocytosis, bacteremia | A cystic defect of right hepatic lobe | Occlusion of the right hepatic artery and right portal vein | Surgery |

| Wang et al[5], 2011 | A 44-year-old man with liver transplantation and TIPS | Refractory hypotension | Rise in serum aminotransferase level | A large, irregular hypodense lesion in the right lobe of the liver | Abrupt truncation of the native common hepatic artery | Aggressive resuscitation |

| Ashida et al[2], 2003 | A 74-year-old man with liver abscess | Diarrhea and abdominal pain | - | Low-density lesions | Interrupt of the hepatic artery and portal vein | Operation and drainage |

| Sakhel et al[16], 2006 | A 39-year-old primigravida with SLE and secondary APS | Upper abdominal pain, tachypnea, dyspnea, and tachycardia | Elevated AST and ALT | Multiple irregularly shaped, small, low-density lesions | Heparin and broad-spectrum antibiotics | |

| Peng et al[19], 2018 | A 30-year-old woman with post-partum hemorrhage | Liver enzyme levels peaked, DIC | Poor enhancement of the right hepatic lobe on the periphery | Liver transplantation |

The causes of liver infarction are complex with an outcome that is sometimes systemic, and can even be fatal. Simple imaging, such as ultrasound, CT scan, or magnetic resonance imaging, is sometimes insufficient, and at least two imaging methods are required. In addition, detailed history taking, physical examination, and related serum studies are also crucial. The treatment of primary diseases, such as APS and SLE, is essential, and treatment with antibiotics, hepatoprotective drugs, thrombolysis, hormones, and even surgery are also significant. We should also be aware of the clinical characteristics, imaging appearance, and serum results of other liver lesions, such as liver cancer and abscess, as the early precise diagnosis of liver infarction is difficult and important for controlling further progression and improving prognosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dogan U, Neri V S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11573] [Cited by in RCA: 13155] [Article Influence: 1879.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Ashida A, Matsukawa H, Samejima J, Fujii K, Adachi H, Ishikawa Y, Kato N, Kawamoto M, Fujisawa J, Rino Y, Imada T. Liver infarction due to liver abscess. Dig Surg. 2008;25:258-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Otani Y, Anzai S, Shibuya H, Fujiwara S, Takayasu S, Asada Y, Terashi H, Takuma M, Yokoyama S. Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS) manifested as necrosis of fingers and toes and liver infarction. J Dermatol. 2003;30:810-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Haratake J, Horie A, Furuta A, Yamato H. Massive hepatic infarction associated with polyarteritis nodosa. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1988;38:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang MY, Potosky DR, Khurana S. Liver infarction after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in a liver transplant recipient. Hepatology. 2011;54:1887-1888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Seeley TT, Blumenfeld CM, Ikeda R, Knapp W, Ruebner BH. Hepatic infarction. Hum Pathol. 1972;3:265-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Saegusa M, Takano Y, Okudaira M. Human hepatic infarction: histopathological and postmortem angiological studies. Liver. 1993;13:239-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mor F, Beigel Y, Inbal A, Goren M, Wysenbeek AJ. Hepatic infarction in a patient with the lupus anticoagulant. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:491-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mayan H, Kantor R, Rimon U, Golubev N, Heyman Z, Goshen E, Shalmon B, Weiss P. Fatal liver infarction after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedure. Liver. 2001;21:361-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Adler DD, Glazer GM, Silver TM. Computed tomography of liver infarction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142:315-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Khong SY, James M, Smith P. Diagnosis of liver infarction postpartum. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1271-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Woller SC, Boschert ME, Hutson WR. Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma presenting as liver infarction. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:xx. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ni Y, Adzamli K, Miao Y, Cresens E, Yu J, Periasamy MP, Adams MD, Marchal G. MRI contrast enhancement of necrosis by MP-2269 and gadophrin-2 in a rat model of liver infarction. Invest Radiol. 2001;36:97-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Arun BR, Padma S, Mallick A, Shanmuga Sundaram P. Unsuspected right lobe liver infarction in Byler's disease--identified by hepatobiliary scintigraphy. Indian J Pediatr. 2014;81:512-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wong MD, Lucas CE. Liver infarction after laparoscopic cholecystectomy injury to the right hepatic artery and portal vein. Am Surg. 2001;67:410-411. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Sakhel K, Usta IM, Hannoun A, Arayssi T, Nassar AH. Liver infarction in a woman with systemic lupus erythematosus and secondary anti-phospholipid and HELLP syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35:405-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | He J, Xiao ZS, Shan YH, Song J. Misdiagnosis of liver infarction after cesarean section in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome during pregnancy. Chin Med J (Engl). 2015;128:282-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Marai I, Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. The systemic nature of the antiphospholipid syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 2004;33:365-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Peng IT, Chung MT, Lin CC. Severe Postpartum Hemorrhage Complicated with Liver Infarction Resulting in Hepatic Failure Necessitating Liver Transplantation. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2018;2018:2794374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yoshihara M, Mayama M, Ukai M, Tano S, Kishigami Y, Oguchi H. Fulminant liver failure resulting from massive hepatic infarction associated with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42:1375-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sawhney R, Wall SD, Yee J, Hayward I. Hepatic infarction: unusual complication of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1997;8:129-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5972] [Cited by in RCA: 6569] [Article Influence: 469.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Park BV, Gaba RC, Lokken RP. Liver Infarction after Drug-Eluting Embolic Transarterial Chemoembolization for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Setting of a Large Portosystemic Shunt. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2016;33:337-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |