Published online May 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i10.1897

Peer-review started: December 31, 2019

First decision: January 16, 2020

Revised: March 27, 2020

Accepted: April 17, 2020

Article in press: April 17, 2020

Published online: May 26, 2020

Processing time: 145 Days and 18.4 Hours

Although total or subtotal colectomy for slow-transit constipation (STC) has been proven to be a definite treatment, the associated defecation function and quality of life (QOL) are rarely studied.

To evaluate the effectiveness of surgery for STC regarding defecation function and QOL.

From March 2013 to September 2017, 30 patients undergoing surgery for STC in our department were analyzed. Preoperative, intra-operative, and postoperative 3-mo, 6-mo, 1-year, and 2-year follow-up details were recorded. Defecation function was assessed by bowel movements, abdominal pain, bloating, straining, laxative, enema use, diarrhea, and the Wexner constipation and incontinence scales. QOL was evaluated using the gastrointestinal QOL index and the 36-item short form survey.

The majority of patients (93.1%, 27/29) stated that they benefited from the operation at the 2-year follow-up. At each time point of the follow-up, the number of bowel movements per week significantly increased compared with that of the preoperative conditions (P < 0.05). Similarly, compared with the preoperative values, a marked decline was observed in bloating, straining, laxative, and enema use at each time point of the follow-up (P < 0.05). Postoperative diarrhea could be controlled effectively and notably improved at the 2-year follow-up. The Wexner incontinence scores at 6-mo, 1-year, and 2-year were notably lower than those at the 3-mo follow-up (P < 0.05). Compared with those of the preoperative findings, the Wexner constipation scores significantly decreased following surgery (P < 0.05). Thus, it was reasonable to find that the gastrointestinal QOL index scores clearly increase (P < 0.05) and that the 36-item short form survey results displayed considerable improvements in six spheres (role physical, role emotional, physical pain, vitality, mental health, and general health) following surgery.

Total or subtotal colectomy for STC is not only effective in alleviating constipation-related symptoms but also in enhancing patients’ QOL.

Core tip: Although total or subtotal colectomy for slow-transit constipation has been proven to be a definite treatment, the associated defecation function and quality of life are rarely studied. The reported outcomes of colectomy for constipation are various, controversial, and conflicting. Based on our study of 2-year follow-up data following surgery, total or subtotal colectomy for slow-transit constipation is not only effective in alleviating constipation-related symptoms but also in enhancing patients’ quality of life.

- Citation: Tian Y, Wang L, Ye JW, Zhang Y, Zheng HC, Shen HD, Li F, Liu BH, Tong WD. Defecation function and quality of life in patients with slow-transit constipation after colectomy. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(10): 1897-1907

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i10/1897.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i10.1897

Constipation is an ever-growing problem and one of the most common gastrointestinal symptoms, affecting 10%–15% of adults in the United States and 8.2% of the general population in China[1,2]. Slow-transit constipation (STC), representing 15%-30% of constipated patients, is characterized by a loss of colonic motor activity[3]. Factors such as increasing age, female sex, physical inactivity, endocrine, metabolism, neurological factors, drug use, and depression are associated with constipation[4]. While most patients have mild constipation that is easily treated with behavioral and medical therapies, a minority of patients suffering from long-term intractable symptoms and poor quality of life (QOL) and showing no response to any medical interventions are ultimately recommended for surgery[5].

Since the effectiveness of colectomy for constipation was first reported by Lane a century ago, surgical treatment for constipation has greatly developed[6] and included ileorectal anastomosis (IRA)[7,8], cecorectal anastomosis (CRA)[9,10], colonic exclusion[11], antegrade enemas (the Malone procedure)[12], modified Duhamel surgery[13], and permanent ileostomy[14]. Currently, the main surgical procedures for STC are IRA and CRA, which have been widely confirmed to increase bowel movement frequency in a huge number of patients[6,9]. However, the reported outcomes of colectomy are controversial and conflicting[15,16]. In these studies, lack of prospectively defined follow-up intervals is a general problem. Moreover, long-term outcomes of surgery for STC are rarely reported[16]. Furthermore, negatively persistent symptoms including abdominal pain, bloating, intractable diarrhea, malnutrition, constipation recurrence, fecal incontinence, and intestinal obstruction are not uncommon following surgery, adversely affecting defecation function and QOL following these procedures[17-19].

This study investigated the effectiveness of total or subtotal colectomy, with respect to short- and long-term defecation function and overall QOL during 2-year regular follow-up.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Daping Hospital. Prospectively, data collected on patients with STC undergoing laparoscopic total (subtotal) colectomy between March 2013 and September 2017 was reviewed. Constipation was defined using the Rome III criteria[20]. Patients were included if every attempt at medical therapy had failed over 1 year. Repeated colonic transit studies were conducted in all patients and defined as positive, when retention of more than 20% markers were localized in the colon after 72 h. Preoperative evaluation of patients with STC included a complete colonoscopy, defecography, and anorectal manometry. The exclusion criteria included a patient for any other indication such as history of carcinomas, polyposis, inflammatory bowel disease, constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome, pelvic floor dyssynergia, and megacolon. Data regarding demographics, preoperative symptoms, preoperative investigations, previous surgery, surgical procedures, and complications were obtained from medical records and analyzed. All surgeries were performed by the same colorectal surgical team. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

All patients were asked to fulfill preoperative questionnaires and answer postoperative questions via telephone during follow-up. The defecation function was assessed by bowel movements (number/wk), abdominal pain, bloating, straining, laxative, enema use, diarrhea, the Wexner constipation and incontinence (WC and WI) scales[21,22]. The QOL was evaluated using the gastrointestinal QOL index (GIQLI)[23] and the 36-item short form (SF-36) survey[24]. Meanwhile, postoperative health changes were included. The follow-up time appointments were scheduled 3 mo, 6 mo, 1 year, and 2 years following surgery. All questionnaires were distributed to the patients by a resident medical doctor in our department with the purpose of rendering the questions more comprehensible to the interviewees than self-administration.

Parameters including bowel movements, WC, WI, GIQLI, and each sphere of the SF-36 were compared before and after surgery. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, and analyzed using a parametrical test (paired samples t-test) or non-parametrical test (Wilcoxon rank sum test). Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test and reported as proportions (percent). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

There were 30 patients with STC, including 26 (86.7%) women and 4 (13.3%) men. The median age at the time of surgery was 50.5 years (range, 25–77 years). The average course of the disease was 11.8 years (range, 2-33 years). Twenty-nine patients were successfully followed up, while one (3.3%) committed suicide for non–surgical related reasons in the 2-year follow-up (Table 1).

| Sex | |

| Female | 26 (86.7) |

| Male | 4 (13.3) |

| Age, yr (range) | 50.5 (25–77) |

| Duration of disease, yr (range) | 11.8 (2–33) |

| Length of hospital stay, d (range) | 9 (6–28) |

| X-ray investigation results | |

| Delayed colonic transit | 30 (100) |

| Redundant colon | 26 (86.7) |

| Internal rectal prolapse | 25 (83.3) |

| Rectocele | 8 (26.7) |

| Colonoscopy results | |

| Melanosis coli | 5 (16.7) |

| Previous abdominal or pelvic floor surgery | 20 (66.7) |

| Transanal surgery (hemorrhoidectomy, PPH) | 11 (36.7) |

| Gynecologic surgery | 9 (30.0) |

| Appendectomy | 3 (10) |

| Sigmoidectomy | 1 (3.3) |

| Rectopexy | 1 (3.3) |

| Cholecystectomy | 1 (3.3) |

| Surgical procedure | |

| Total colectomy with IRA | 23 (76.7) |

| Subtotal colectomy with CRA | 7 (23.3) |

| Operative approach | |

| Laparoscopy | 18 (60.0) |

| Hand-assisted laparoscopy | 7 (23.3) |

| Single incisional laparoscopy | 3 (10.0) |

| Robotic-assisted | 2 (6.7) |

The colonic transit time was prolonged in all patients, with a mean of 82% and a range of 55%-100% on day 3 of the study. Barium enema showed an extremely redundant transverse or left colon in 26 patients (86.7%). Abnormal findings of defecography were mild rectal prolapse in 25 patients (83.3%) and rectoceles in 8 patients (26.7%). Melanosis coli was present in 5 patients (16.7%) as observed by complete colonoscopies (Table 1).

Twenty patients (66.7%) had a history of abdominal or pelvic floor surgery. Eleven (36.7%) cases had a previous transanal surgery. Nine (30.0%) cases had a previous gynecologic surgery. Three (10.0%) had undergone surgery for appendicitis. One (3.3%) had a previous sigmoidectomy for the redundant sigmoid colon. One (3.3%) had a previous rectopexy. One (3.3%) had undergone cholecystectomy (Table 1).

The surgical procedures including IRA (23, 76.7%) and CRA (7, 23.3%) were conducted via hand-assisted laparoscopy (18, 60.0%), laparoscopy (7, 23.3%), single incisional laparoscopy (3, 10.0%), and robotic-assisted laparoscopy (2, 6.7%). The anastomosis was stapled in all patients (Table 1).

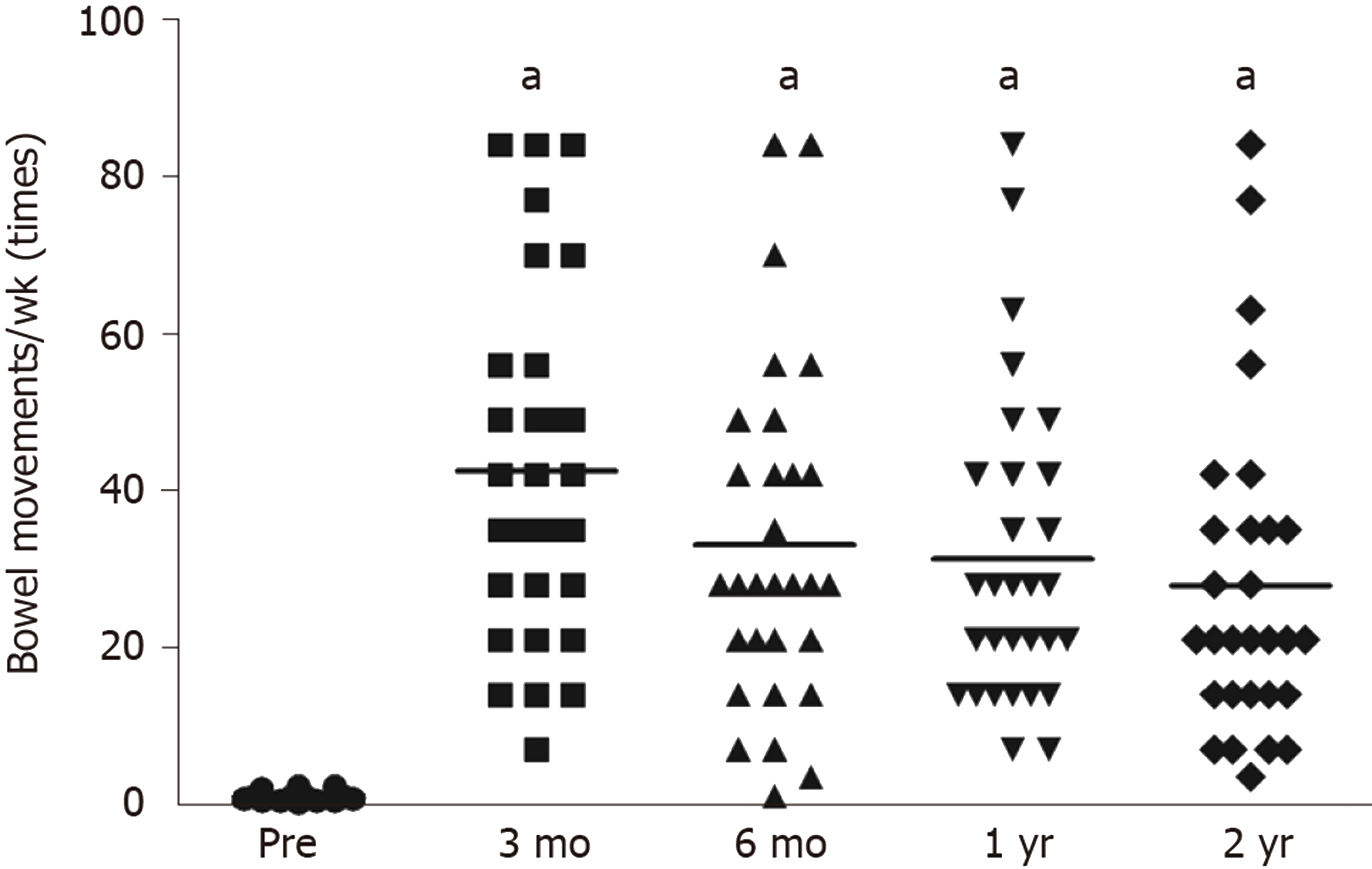

The number of bowel movements per week with the aid of laxatives was 1.2 ± 0.6 before surgery. The findings at each time point follow-up significantly increased (P < 0.05) and the increased frequency of defecation following the procedure was controlled over time (Table 2 and Figure 1).

| Preoperative | Postoperative | ||||

| 3 mo | 6 mo | 1 yr | 2 yr | ||

| Number of patients, follow-up | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 29 |

| Bowel movements/wk | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 42.5 ± 22.3a | 33.0 ± 21.6a | 31.3 ± 19.6a | 27.9 ± 20.5a2 |

| WC | 20.4 ± 4.1 | 5.9 ± 3.4a | 6.2 ± 4.1a | 5.5 ± 3.4a | 5.0 ± 3.7a1 |

| WI | - | 2.7 ± 3.6 | 1.0 ± 2.1a | 1.2 ± 2.7a | 1.1 ± 2.1c2 |

| Abdominal pain | 17 (56.7) | 18 (60) | 15 (50.0) | 12 (40) | 6 (20.7)a3 |

| Bloating | 29 (96.7) | 14 (46.7)a | 15 (50.0)a | 12 (40)a | 7 (24.1)a3 |

| Diarrhea | - | 23 (76.7) | 18 (60) | 17 (56.7) | 14 (48.3)c3 |

| Straining | 30 (100.0) | 3 (10.0)a | 6 (20.0) a | 5 (16.7)a | 5 (17.2)a3 |

| Laxative | 29 (96.7) | 0 (0)a | 0 (0)a | 0 (0)a | 1 (3.5)a3 |

| Enema use | 21 (70) | 2 (6.7)a | 5 (16.7)a | 3 (10.0)a | 2 (6.9)a3 |

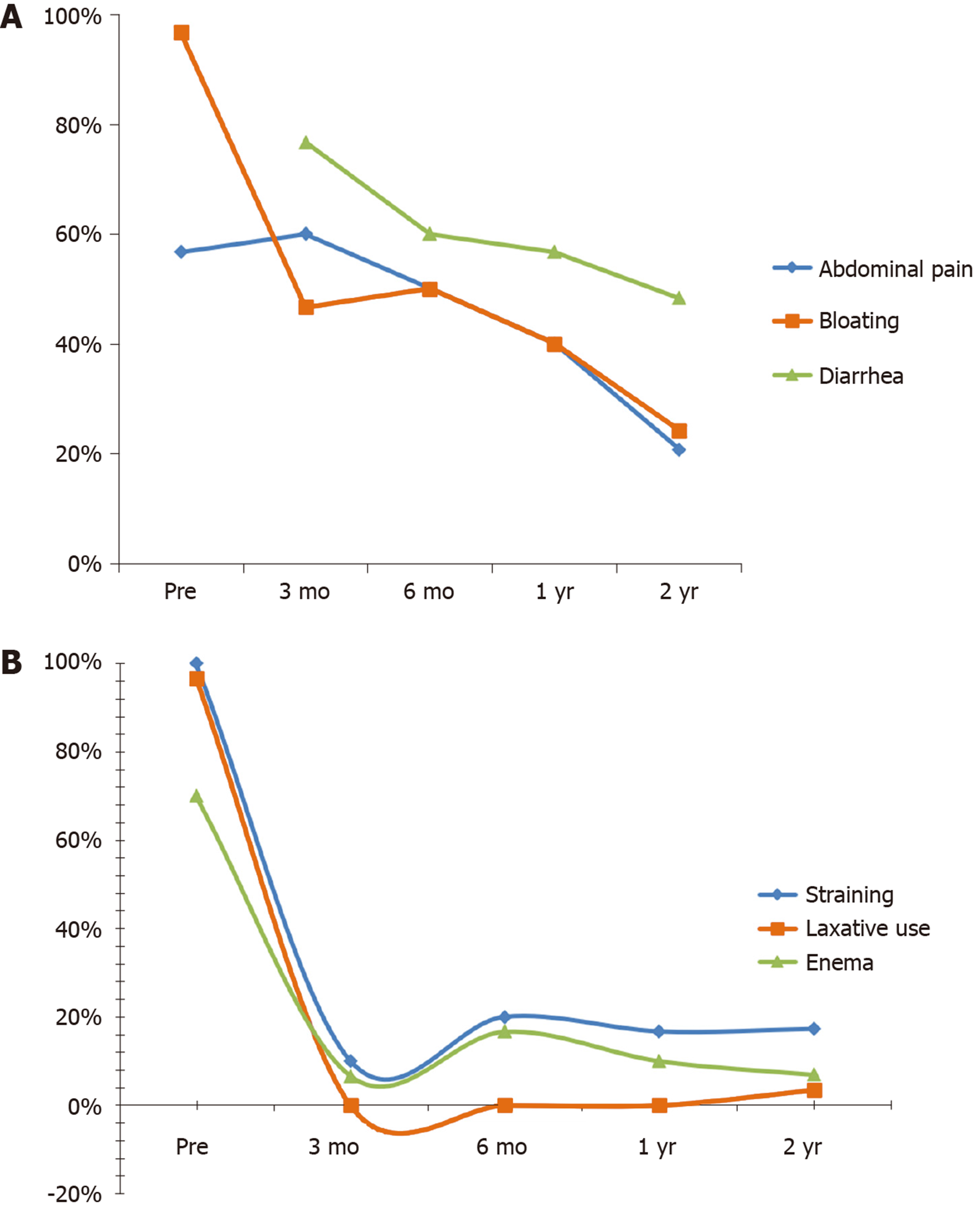

Compared with those of the preoperative findings, a remarkable decline was observed in bloating, straining, laxative and enema use at each time point follow-up (P < 0.05), in addition to that in abdominal pain at the 2-year follow-up (P < 0.05). There is no severe diarrhea after surgery, although occasional diarrhea was present in 23 patients (76.6%) during the 3-mo follow-up. The incidence rate of diarrhea was notably lower at the 2-year follow-up than that at the 3-mo follow-up (P < 0.05) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

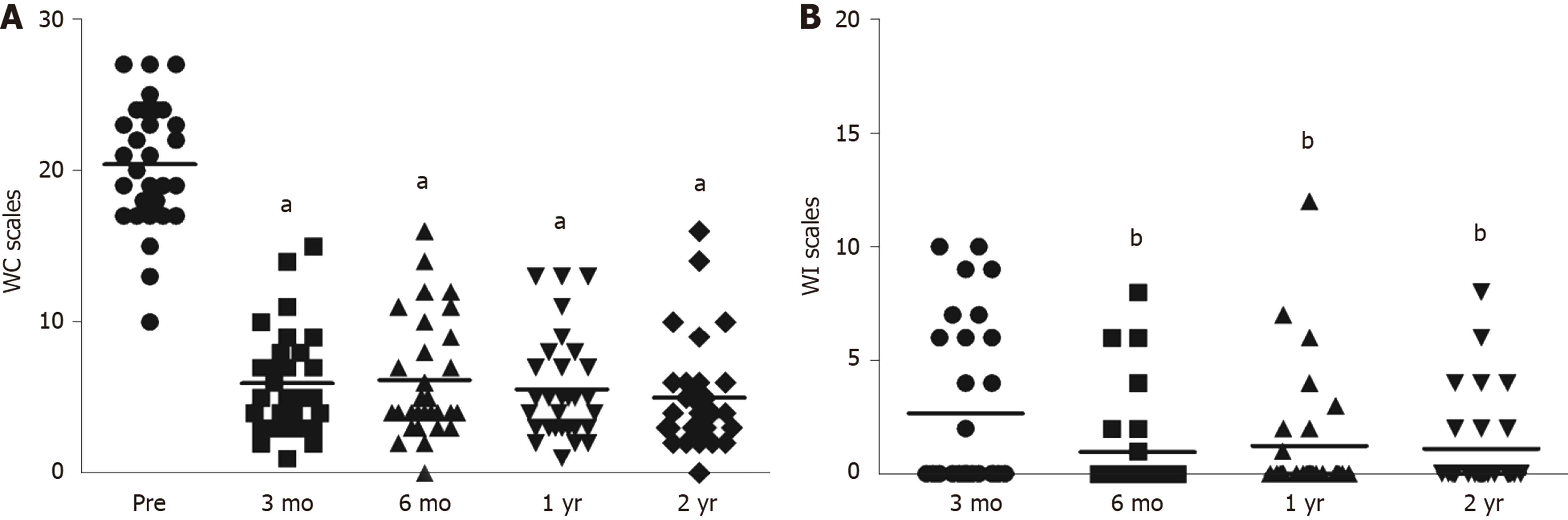

The WC scores significantly decreased at each time point during follow-up (P < 0.05) compared with those of the preoperative findings. A stable trend in WC scores was observed following surgery (Table 2 and Figure 3A).

Compared to the findings at the 3-mo follow-up, WI scores were notably lower at the 6-mo, 1-year and 2-year follow-up (P < 0.05) (Table 2 and Figure 3A). Based on the WI rating standard, no complete fecal incontinence was observed, and 12 patients (40%) had occasional incontinence 3 mo after surgery. Of these patients, 4 (13.3%) used pads for fecal incontinence (Table 2 and Figure 3B).

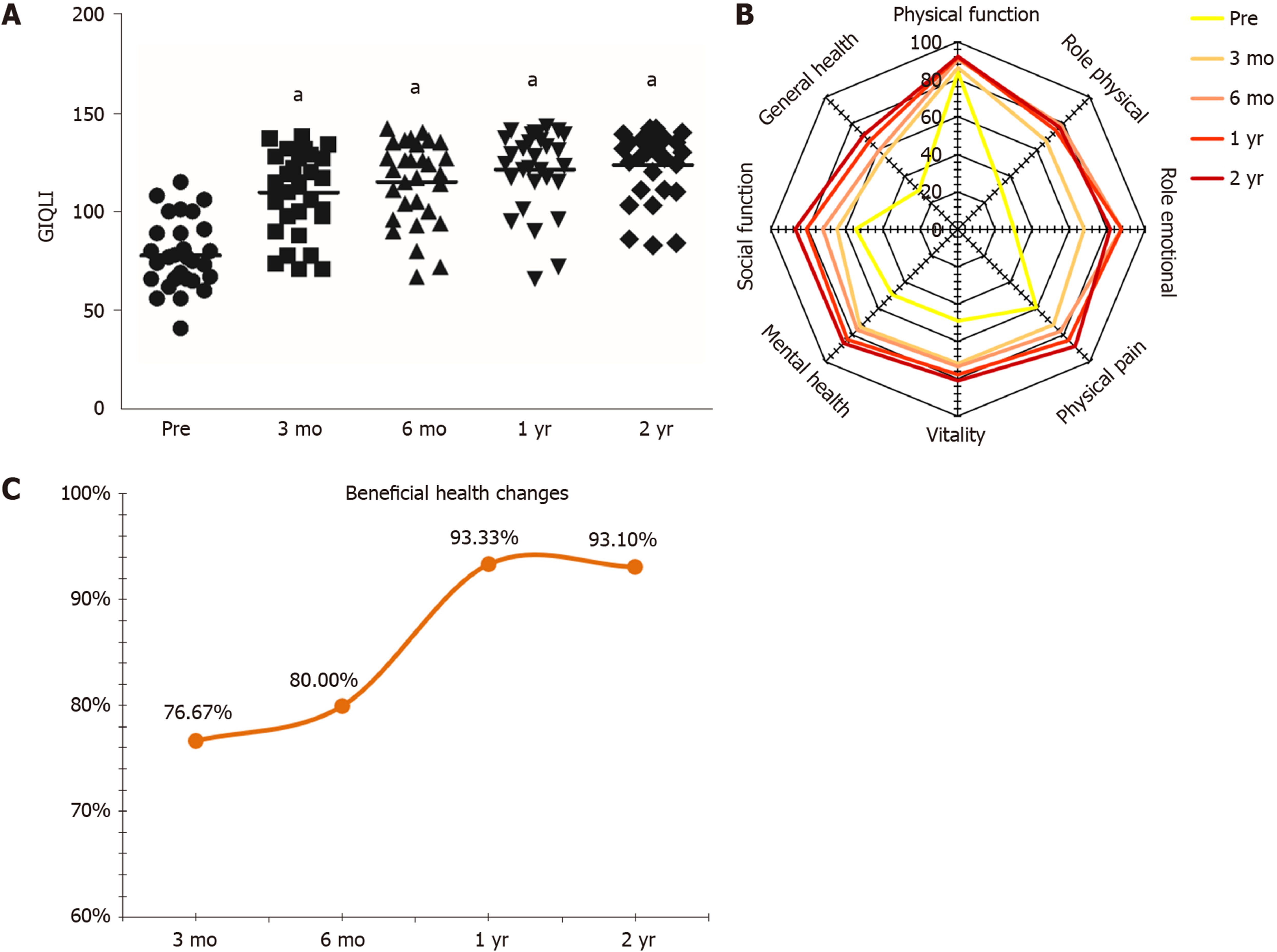

In compare with those of the preoperative conditions, GIQLI scores went up obviously at each follow-up time point (P < 0.05) (Table 3 and Figure 4A).

| Preoperative | Postoperative | ||||

| 3 mo | 6 mo | 1 yr | 2 yr | ||

| GIQLI | 77.8 ± 17.5 | 109.7 ± 21.2a | 115.0 ± 20.7a | 121.3 ± 20.3a | 123.6 ± 17.5a1 |

| SF-36 sphere | |||||

| Physical function | 83.8 ± 20.2 | 86.3 ± 16.1 | 90.7 ± 9.7 | 91.8 ± 10.9 | 92.2 ± 11.52 |

| Role physical | 32.5 ± 46.0 | 66.7 ± 44.7a | 78.3 ± 38.7a | 74.4 ± 37.7a | 76.7 ± 38.9a1 |

| Role emotional | 30.0 ± 46.6 | 67.8 ± 44.2a | 87.8 ± 28.4a | 87.8 ± 30.9a | 81.6 ± 36.3a2 |

| Physical pain | 59.2 ± 31.8 | 72.2 ± 24.7a | 77.4 ± 28.7a | 83.9 ± 25.6a | 88.9 ± 23.5a1 |

| Vitality | 49.0 ± 28.9 | 71.7 ± 27.4a | 73.5 ± 25.6a | 78.0 ± 26.1a | 80.9 ± 23.0a1 |

| Mental health | 49.5 ± 26.5 | 74.0 ± 25.9a | 76.3 ± 26.6a | 83.7 ± 25.1a | 86.2 ± 21.3a1 |

| Social function | 54.6 ± 39.3 | 64.6 ± 31.2 | 72.1 ± 30.0a | 80.8 ± 31.6a | 87.1 ± 24.0a2 |

| General health | 29.4 ± 26.6 | 55.6 ± 27.5a | 56.6 ± 28.3a | 66.6 ± 33.0a | 71.1 ± 30.0a1 |

The results of the SF-36 showed considerable improvements in role physical, role emotional, physical pain, vitality, mental health, and general health spheres at each time point after surgery compared to the preoperative scores (P < 0.05), in addition to those in social function at 6-mo, 1-year, and 2-year follow-up (P < 0.05). No obvious difference was recorded in physical function before and after the procedure (P > 0.05) (Table 3 and Figure 4B).

According to the follow-up findings of postoperative health changes, 23/30 (76.7%) patients stated that they received benefits from the procedure at 3-mo follow-up and this percentage reached more than 90% 1 year after colectomy. At the 2-year follow-up, 27 of 29 patients (96.7% of the respondents) stated that the surgery had been beneficial to their health. Of these, 18 (60%) stated that they were much better, and 9 (30%) said that they had improved. One patient (3.3%) did not think that the surgery had been beneficial, and one (3.3%) felt much worse after surgery (Figure 4C).

The median length of hospital stay was 9 d (range, 6–28 d). No procedure-related death occurred within 30 d after surgery. No patient exhibited anastomotic bleeding or incision infections. Two patients (6.6%) had early anastomotic leakage with ileus and were managed conservatively.

Long-term complications occurring 90 d following surgery were documented during follow-up. Small intestinal obstruction was the most common postoperative complication in 6 (20%) patients in which 2 (6.7%) underwent surgical intervention for enterolysis after 8 mo and 10 mo of the colectomy. Constipation recurrence was observed in 1 patient (3.3%) 1 mo following surgery, requiring enemas every morning. Trocar site hernia was found in 1 patient (3.3%) 3 mo after surgery.

The principal goals of colectomy in patients with STC are to relieve constipation and increase the number of bowel movements. It has been proved that total and subtotal colectomy are beneficial to STC patients, with more than 80% satisfaction reported in some studies[7,25,26]. However, persistent symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, as well as incontinence, and complications are not uncommon after surgery. Meanwhile, a recent systematic review reported by Knowles suggested that current evidence was characterized by the lack of prospectively defined follow-up intervals and uncertain methodological quality[16]. It is difficult and insufficient to quantify and to express the effects of surgery on postoperative defecation function and QOL[16,27]. Unfortunately, the remission of constipation does not necessarily improve the QOL. In fact, the postoperative defecation function and the QOL are always overlooked[28]. Thus, to further evaluate the outcomes of colectomy for STC, the GIQLI, SF-36 survey, WC and WI scales with planned follow-up intervals have been used to assess the defecation function and QOL.

In terms of defecation function, the postoperative increased frequency of bowel movements in the short-term is noteworthy. In our study, a great majority of patients during the hospital stay following surgery were observed to defecate 10-20 times/d, and some patients were even up to more than 20 times/d, requiring an anti-diarrheal agent and adult diapers. The number of bowel movements/wk was 42.5 ± 22.3 during the 3-mo follow-up, and our data showed a downstream trend in the bowel-movement frequency following the procedure, with 27.9 ± 20.5 times/wk during the 2-year follow-up, suggesting that the increased frequency of bowel movements after colectomy could be controllable over time. Compared to the preoperative findings, remarkable improvements were observed in bloating, straining, laxative, and enema use at each time point during follow-up (P < 0.05), in addition to that in abdominal pain at the 2-year follow-up (P < 0.05). None of patient experienced severe diarrhea following the procedure, although more than half of patients complained of occasional diarrhea after surgery, which was closely related to their individual differences and dietary habits such as intake of milk, fat, chilies and cold food. These results suggest that defecation-related symptoms can be improved by surgery, a conclusion also reported by Li et al[25], Marchesi et al[27], and Wei et al[29].

The WC scale is a validated questionnaire designed to quantify a patient’s constipation level[21]. Our results showed significantly decreased WC scores at 3-mo follow-up compared with those in preoperative conditions (P < 0.05), with a stable trend over time postoperatively. However, one patient experienced recurrent constipation 1 mo after colectomy, requiring daily enemas use. This case might involve rectal inertia. Our data (mean 5.0, 30 cases) on WC scores was better than other previous studies (mean 6.0, 33 cases, in the series of Ripetti et al[18]) (a median of 11.5, range 8-23, 12 cases, in the series of Riss et al[19]).

The WI scale in our study was used to quantify fecal incontinence and frequency[22]. Compared to the findings at the 3-mo follow-up, the WI scores were notably lower at 6-mo, 1-year, and 2-year follow-up (P < 0.05). No complete fecal incontinence was observed, while 12 patients (40%) had occasional incontinence at the 3-mo follow-up, 4 of whom (13.3%) used pads for fecal incontinence. The most severe case was a 55-year-old female patient who had a small amount of liquid feces staining on pads with anal pendant expansion daily. The mean WI scores (mean 1.1, range 0-8, 30 cases) in our study were lower than those of the study by Marchesi et al[27] (mean 3, range 0-18, 22 cases), with the number of patients in occasional incontinence (12, 40%) lower than those in the Thaler’s study (17, 47%)[30].

In terms of the QOL, the GIQLI is a validated and internationally adopted QOL questionnaire to evaluate gastrointestinal symptoms by Eypasch et al[23] in 1995. Our results showed that GIQLI scores clearly increased (P < 0.05) at each follow-up time point compared to the preoperative scores, and continual improvement was observed during the 2-year follow-up (123.5 ± 17.5 in 30 cases), which was better than previous reports by FitzHarris et al[31] (103 ± 22 in 75 patients, follow-up 1-10 years) and Marchesi et al[27] (115.5 ± 20.5 in 22 patients, follow-up 1-12 years), and was close to the mean score reported for healthy people (125.8 ± 13)[23].

The SF-36 health survey is a standard tool used to evaluate the QOL and has been used previously to evaluate STC patients with total colectomy[30-32]. At each follow-up time point after surgery, the SF-36 showed considerable improvements in six spheres (role physical, role emotional, physical pain, vitality, mental health, and general health) over the preoperative baseline (P < 0.05), in addition to those in social function at the 6-mo, 1-year, and 2-year follow-up (P < 0.05). No significant difference was observed in physical function before and after surgery (P > 0.05). Our results were worse than those of the study of Vergara-Fernandez et al[32] (8 spheres, 10 cases, follow-up 1 year) and better than those of the study of Ripetti et al[18] (4 spheres, 33 cases, follow-up 1–10 years)[18]. It was reported by FitzHarris et al[31] that the QOL in STC patients following surgery was affected by abdominal pain, diarrhea and incontinence. Marchesi et al[27] also reported that abdominal pain was a common epiphenomenon and a notable negative correlation was observed between GIQLI scores and the abdominal pain. In our study, more than half patients experienced intermittent abdominal pain at the 3-mo follow-up and the incidence rate clearly decreased at the 2-year follow-up compared to preoperative findings (P < 0.05). In addition to the considerable increase in physical pain scores of SF-36 following surgery, our results suggest that both the incidence rate and degree of abdominal pain improved significantly. Such pain, likely caused by surgery-related adhesions, was better in our study than in that in the report of Thaler et al[30] (41%).

Short-term complications occurred in 2 patients (6.7%) within 30 d after surgery. Both patients presented with anastomotic leakage on postoperative days 7 and 9, respectively, as well as the ileus, and were treated conservatively including fasting, water-deprivation, anti-infective treatment, somatostatin by micropump and patent drainage. In this study, 6 (20%) patients were diagnosed with small intestinal obstruction, which was the most common postoperative complications. Four of these (13.3%) healed with conservative management, while other 2 (6.7%) cases required surgical intervention for enterolysis after 8 and 10 mo of the initial surgery. Other reports on the incidence of small intestinal obstruction were diverse (Sohn et al[7], 18.9%; Zutshi et al[17], 46%; Li et al[25], 32.5%; Reshef et al[26], 54% and Marchesi et al[27], 9.1%). It has been reported that laparoscopic minimally invasive surgery for the reduction of postoperative abdominal adhesion was superior to open surgery[33]. One patient experienced constipation recurrence after 1 mo of surgery, requiring an enema every morning. In this patient, the total digestive tract contrast examination with iohexol showed that the contrast agent stopped at the anastomosis, and no anastomosis stenosis was observed in a colonoscopy, indicating that the constipation recurrence may be related to rectal inertia. Trocar site hernia was found in one patient that was cured by herniorrhaphy 3 mo after the initial surgery.

When questioned about postoperative health changes, 23 of 30 (76.7%, 100% of respondents) patients stated that they received benefits from the procedure during the 3-mo follow-up, while it reached more than 90% in the 1-year follow-up. In the 2-year follow-up, 27 of 29 (93.1%, 96.7% of respondents) stated that the surgery was beneficial to their health. Among these patients, 18 (60%) stated they obtained great deal of improvement, while 9 (30%) said that their health had improved. Unfortunately, one (3.3%) patient complained that the operation did not benefit her, the other one (3.3%) felt much worse after surgery.

Since this is a retrospective single-center study which has certain limitations, multicenter randomized controlled studies are necessary in future. In addition, we will also expand the sample size and perform long term continuous follow-up to further evaluate the defecation function and the QOL for surgery.

In our study, a drastically increase in bowel movements, a significant decrease in WC scores and remarkable improvements in associated symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, straining, laxative and enema use suggest that total or subtotal colectomy is efficient in the treatment of STC. A marked trend toward increasing GIQLI scores was observed following surgery and SF-36 displayed great improvement in 6 spheres. Furthermore, the majority of patients (93.1%) thought that they benefit from the procedure during the 2-year follow-up (Supplementary Table 1). These results suggest that the QOL improved after the procedure. Our results revealed that total or subtotal colectomy for STC is effective in treating patients with colonic inertia.

Slow-transit constipation (STC) is characterized by a loss in the colonic motor activity. A minority of patients suffering from long-term intractable symptoms and poor quality of life (QOL) and showing no response to any medical interventions are ultimately recommended for surgery. Currently, the main surgical procedures for STC are ileorectal anastomosis and cecorectal anastomosis.

However, the reported outcomes of colectomy are controversial and conflicting. In these studies, lack of prospectively defined follow-up intervals is a general problem. Moreover, long-term outcomes of surgery for STC are rarely reported. Furthermore, negatively persistent symptoms including abdominal pain, bloating, intractable diarrhea, malnutrition, constipation recurrence, fecal incontinence, and intestinal obstruction are not uncommon following surgery, adversely affecting defecation function and QOL following these procedures.

This study investigated the effectiveness of total or subtotal colectomy, with respect to short- and long-term defecation function and overall QOL during 2-year regular follow-up.

From March 2013 to September 2017, 30 patients undergoing surgery for STC in our department were analyzed. Preoperative, intra-operative, and postoperative 3-mo, 6-mo, 1-year, 2-year follow-up details were recorded. Defecation function was assessed by bowel movements, abdominal pain, bloating, straining, laxative, enema use, diarrhea, and the Wexner constipation and incontinence scales. QOL was evaluated using the gastrointestinal QOL index and the short-form-36 survey.

The majority of patients (93.1%, 27/29) stated that they benefit from the operation at the 2-year follow-up. At each time point of the follow-up, the number of bowel movements per week increased significantly compared with that of the preoperative conditions (P < 0.05). Similarly, compared with the preoperative values, a marked decline was observed in bloating, straining, laxative, and enema use at each time point of following up (P < 0.05). Postoperative diarrhea could be controlled effectively and improved notably at the 2-year follow-up. The Wexner incontinence scores at 6-mo, 1-year, and 2-year were notably lower when compared with those at the 3-mo follow-up (P < 0.05). Compared with those of the preoperative findings, the Wexner constipation scores significantly decreased following surgery (P < 0.05). Thus, was reasonable to find that the gastrointestinal QOL index scores clearly increased (P < 0.05) and the 36-item short form results displayed considerable improvements in six spheres (role physical, role emotional, physical pain, vitality, mental health, and general health) following surgery.

Total or subtotal colectomy for STC is not only effective in alleviating constipation-related symptoms but also in enhancing patients’ QOL.

Because this was a retrospective single-center study with certain limitations, multicenter randomized controlled studies are necessary in the future. In addition, we will also expand the sample size and perform long-term continuous follow-up to further evaluate defecation function and QOL after surgery.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Chunxue Li, Dr. Song Zhao, Dr. Yu Gao, Dr. Bin Huang, nurse Xiao-Lian Deng, and the other members of our institute staff for their assistance in this study.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Raptis D, Zikos TA S-Editor: Wang YQ L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Suares NC, Ford AC. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1582-1591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 674] [Cited by in RCA: 578] [Article Influence: 41.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chu H, Zhong L, Li H, Zhang X, Zhang J, Hou X. Epidemiology characteristics of constipation for general population, pediatric population, and elderly population in china. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014;2014:532734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Frattini JC, Nogueras JJ. Slow transit constipation: a review of a colonic functional disorder. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2008;21:146-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bharucha AE, Wald A. Chronic Constipation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:2340-2357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bharucha AE, Rao SSC, Shin AS. Surgical Interventions and the Use of Device-Aided Therapy for the Treatment of Fecal Incontinence and Defecatory Disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1844-1854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Knowles CH, Scott M, Lunniss PJ. Outcome of colectomy for slow transit constipation. Ann Surg. 1999;230:627-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sohn G, Yu CS, Kim CW, Kwak JY, Jang TY, Kim KH, Yang SS, Yoon YS, Lim SB, Kim JC. Surgical outcomes after total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis in patients with medically intractable slow transit constipation. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2011;27:180-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Han EC, Oh HK, Ha HK, Choe EK, Moon SH, Ryoo SB, Park KJ. Favorable surgical treatment outcomes for chronic constipation with features of colonic pseudo-obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4441-4446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sarli L, Costi R, Sarli D, Roncoroni L. Pilot study of subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic cecoproctostomy for the treatment of chronic slow-transit constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1514-1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Marchesi F, Percalli L, Pinna F, Cecchini S, Ricco' M, Roncoroni L. Laparoscopic subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic cecorectal anastomosis: a new step in the treatment of slow-transit constipation. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1528-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Qian Q, Jiang C, Chen Y, Ding Z, Wu Y, Zheng K, Qin Q, Liu Z. A modified total colonic exclusion for elderly patients with severe slow transit constipation. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:629-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Meurette G, Lehur PA, Coron E, Regenet N. Long-term results of Malone's procedure with antegrade irrigation for severe chronic constipation. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:209-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jiang J, Li N, Zhu WM, Li JS. Efficacy and safety of combined use of subtotal colectomy and modified Duhamel procedure in the surgical treatment of severe functional constipation. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2007;10:115-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Scarpa M, Barollo M, Keighley MR. Ileostomy for constipation: long-term postoperative outcome. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:224-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wilkinson-Smith V, Bharucha AE, Emmanuel A, Knowles C, Yiannakou Y, Corsetti M. When all seems lost: management of refractory constipation-Surgery, rectal irrigation, percutaneous endoscopic colostomy, and more. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30:e13352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Knowles CH, Grossi U, Chapman M, Mason J; NIHR CapaCiTY working group; Pelvic floor Society. Surgery for constipation: systematic review and practice recommendations: Results I: Colonic resection. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19 Suppl 3:17-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zutshi M, Hull TL, Trzcinski R, Arvelakis A, Xu M. Surgery for slow transit constipation: are we helping patients? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:265-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ripetti V, Caputo D, Greco S, Alloni R, Coppola R. Is total colectomy the right choice in intractable slow-transit constipation? Surgery. 2006;140:435-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Riss S, Herbst F, Birsan T, Stift A. Postoperative course and long term follow up after colectomy for slow transit constipation--is surgery an appropriate approach? Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:302-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1377-1390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1467] [Cited by in RCA: 1476] [Article Influence: 77.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Agachan F, Chen T, Pfeifer J, Reissman P, Wexner SD. A constipation scoring system to simplify evaluation and management of constipated patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 818] [Cited by in RCA: 851] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jorge JM, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:77-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2089] [Cited by in RCA: 1967] [Article Influence: 61.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Eypasch E, Williams JI, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ure BM, Schmülling C, Neugebauer E, Troidl H. Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index: development, validation and application of a new instrument. Br J Surg. 1995;82:216-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 852] [Cited by in RCA: 881] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ware JE, Gandek B. Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:903-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1606] [Cited by in RCA: 1752] [Article Influence: 64.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Li F, Fu T, Tong W, Zhang A, Li C, Gao Y, Wu JS, Liu B. Effect of different surgical options on curative effect, nutrition, and health status of patients with slow transit constipation. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1551-1556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Reshef A, Alves-Ferreira P, Zutshi M, Hull T, Gurland B. Colectomy for slow transit constipation: effective for patients with coexistent obstructed defecation. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:841-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Marchesi F, Sarli L, Percalli L, Sansebastiano GE, Veronesi L, Di Mauro D, Porrini C, Ferro M, Roncoroni L. Subtotal colectomy with antiperistaltic cecorectal anastomosis in the treatment of slow-transit constipation: long-term impact on quality of life. World J Surg. 2007;31:1658-1664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Serra J, Mascort-Roca J, Marzo-Castillejo M, Delgado Aros S, Ferrándiz Santos J, Rey Diaz Rubio E, Mearin Manrique F. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of constipation in adults. Part 1: Definition, aetiology and clinical manifestations. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:132-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wei D, Cai J, Yang Y, Zhao T, Zhang H, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Cai F. A prospective comparison of short term results and functional recovery after laparoscopic subtotal colectomy and antiperistaltic cecorectal anastomosis with short colonic reservoir vs. long colonic reservoir. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Thaler K, Dinnewitzer A, Oberwalder M, Weiss EG, Nogueras JJ, Efron J, Vernava AM, Wexner SD. Quality of life after colectomy for colonic inertia. Tech Coloproctol. 2005;9:133-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | FitzHarris GP, Garcia-Aguilar J, Parker SC, Bullard KM, Madoff RD, Goldberg SM, Lowry A. Quality of life after subtotal colectomy for slow-transit constipation: both quality and quantity count. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:433-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Vergara-Fernandez O, Mejía-Ovalle R, Salgado-Nesme N, Rodríguez-Dennen N, Pérez-Aguirre J, Guerrero-Guerrero VH, Sánchez-Robles JC, Valdovinos-Díaz MA. Functional outcomes and quality of life in patients treated with laparoscopic total colectomy for colonic inertia. Surg Today. 2014;44:34-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |