Published online Jan 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i1.20

Peer-review started: October 14, 2019

First decision: December 4, 2019

Revised: December 4, 2019

Accepted: December 13, 2019

Article in press: December 13, 2019

Published online: January 6, 2020

Processing time: 84 Days and 1.9 Hours

Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) is a critical and poorly managed complication of ERCP. Endoscopists need to understand the risk factors for PEP. However, the majority of studies investigating ERCP-related risk factors have included well-trained endoscopists, with the issue of endoscopist experience on PEP incidence not having been systematically evaluated.

To explore the risk factors for PEP in beginner endoscopists without supervision.

We performed a retrospective analysis of 293 patients, with naïve papilla and no history of pancreatitis, treated using bile duct cannulation. Patients were classified according to the endoscopist’s experience (beginner vs expert). The angle of the distal common bile duct (CBD) was measured as the angle between the lower wall of the bile duct and a vertical line extending to the lower wall of the bile duct on coronal view computed tomography.

After propensity matching, there were no differences between patients treated by the expert and beginner endoscopist with regard to age, sex, mean bile duct dilatation, and ratio of benign disease. The distal CBD angle was classified as acute (> 30º) or obtuse (≤ 30º), based on the mean angle of 29.9º for the group. An acute distal CBD angle was a significant risk factor for PEP for beginner (P = 0.049), but not expert.

For beginner endoscopists first performing unsupervised ERCP, cases with an obtuse distal CBD angle may be more appropriate to lower the risk of PEP.

Core tip: The most studies investigating endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)-related risk factors have included well-trained endoscopists, with the issue of endoscopist experience on post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) incidence not having been systematically evaluated. Our retrospective study aims to explore the risk factors for PEP in beginner endoscopists without supervisor. Our data showed that acute distal common bile duct (CBD) angle was the only significantly risk factor of PEP in novice endoscopist. The acute distal CBD angle could be known before the procedure. Therefore, beginners can avoid these cases or perform with supervisor to reduce the PEP rate. Obtuse distal CBD angle may be more appropriate to beginner endoscopist.

- Citation: Han SY, Kim DU, Lee MW, Park YJ, Baek DH, Kim GH, Song GA. Acute distal common bile duct angle is risk factor for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis in beginner endoscopist. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(1): 20-28

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i1/20.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i1.20

Currently, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is widely used as a diagnostic and therapeutic modality for pancreaticobiliary disease. Although ERCP is considered to be a relatively safe procedure, adverse events may arise and may be fatal. Therefore, endoscopists need to be aware of the potential for adverse events occurring during ERCP, understand the risk factors for such events, and know how to manage emergent events[1]. Adverse events associated with ERCP can range from post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) to bleeding and perforation. Of these, PEP is the most important and common adverse event, with the incidence rate ranging between 1.6% and 16.7%[1,2]. A recent meta-analysis reported a prevalence rate of 9.7% (95%CI: 8.6%-10.7%)[3]. The European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy has indicated that an incidence rate of < 10% would be appropriate[4].

To lower the risk of PEP, identification of risk factors is a necessary first step. Risk factors can be divided into two major groups, namely patient- and procedure-related. Known patient-related factors for PEP include female sex, young age, prior history of PEP, normal bilirubin, non-dilated bile ducts, and suspicion of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Procedure-related risk factors are as follows: difficult cannulation, precut sphincterotomy, wire cannulation into the pancreatic duct, and contrast injection into the pancreatic duct[5]. In these high-risk groups, the incidence of pancreatitis can be reduced through prophylactic pancreatic stent placement[6,7] or use of rectal non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs[8]. However, the majority of studies investigating ERCP-related risk factors have included well-trained endoscopists, with the issue of endoscopist experience on PEP incidence not having been systematically evaluated[9-11].

Training is essential to developing ERCP expertise. Identifying and avoiding risk factors for beginner endoscopists, who experience a relatively higher incidence rate of PEP than expert endoscopists, may lead to the reduction of PEP. Therefore, the aim of our study was to evaluate the risk factors for PEP among beginner endoscopists, to identify any differences in risk factors compared to expert endoscopists. Identification of risk factors specific to beginner endoscopists would be helpful in selecting appropriate cases for ERCP training.

Our retrospective analysis included 293 ERCP performed at our hospital between June 2017 and November 2017; 196 performed by an expert (Kim DU; > 5000 ERCP procedures) and 97 by a beginner who had completed the required 1-year of supervised training (Han SY; > 100 supervised ERCP procedures and no independent ERCP procedures prior to June 2017). Cases were screened based on the following exclusion criteria: Previous ERCP; biliary pancreatitis at admission; unavailability of a coronal reconstruction view computed tomography (CT) image; and difficulty in identifying the distal common bile duct (CBD) angle on coronal CT images. For analysis, cases were classified according to the endoscopist’s level of experience (expert vs beginner) and distal CBD angle.

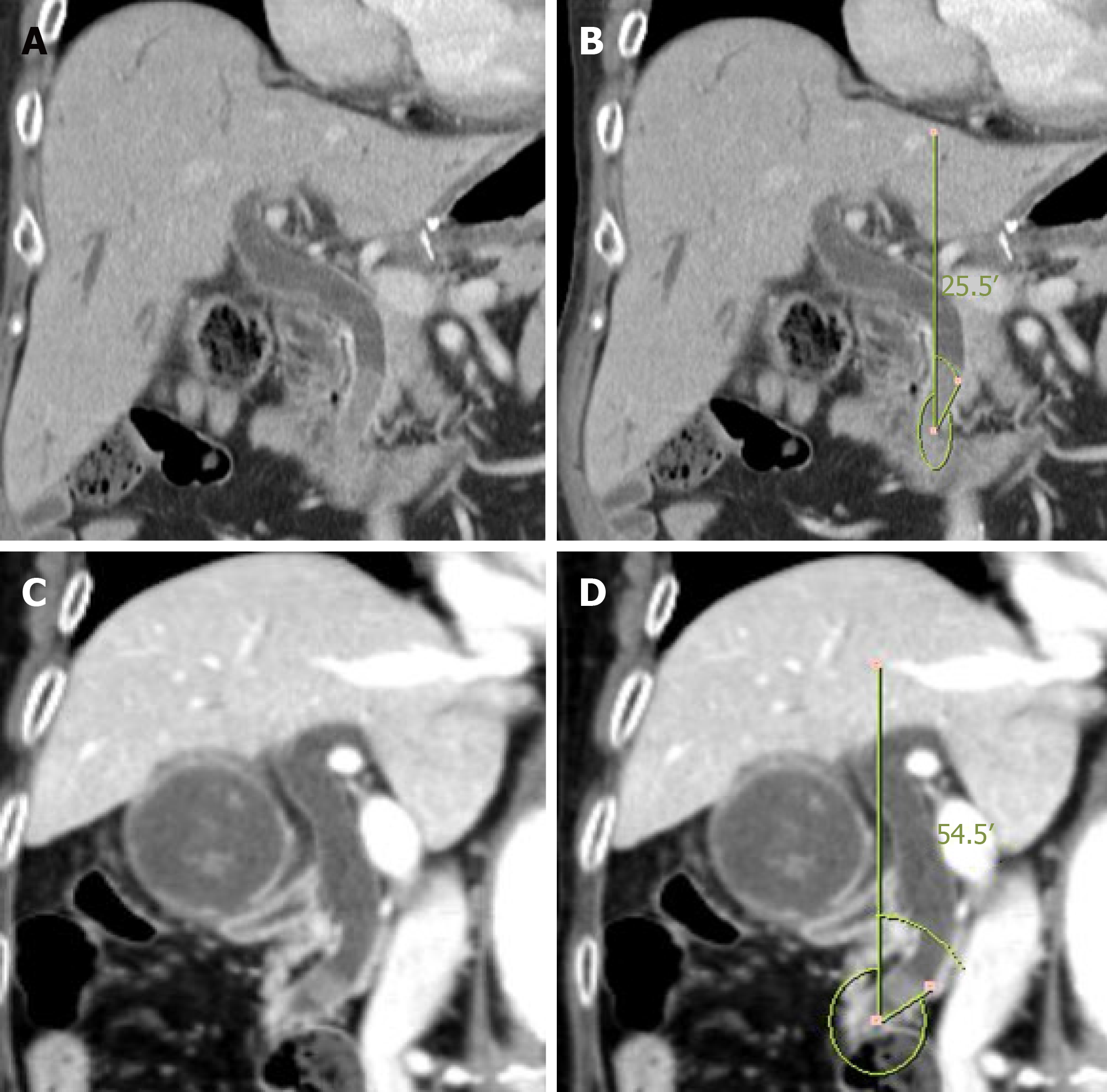

The distal CBD angle was defined relative to a vertical line drawn on the lower wall of the bile duct on coronal CT images. The mean distal CBD angle for the 293 patients included in our study group was approximately 30º. Based on this mean angle value, cases were classified into an acute CBD angle group (< 30º) and an obtuse angle group (≥ 30º); an example of an acute and obtuse CBD angle is provided in Figure 1.

Heterogeneity was identified between cases in the expert and beginner group at baseline, with a higher proportion of malignancy in the bile duct in the expert group and a higher proportion of benign disease in the beginner group. The distribution of sex and diameter of the bile duct was also different between the two groups. To balance the groups on these baseline parameters, the groups were matched using a propensity score that included sex, diameter of the bile duct, and benign disease.

All ERCP procedures were performed using a duodenoscope (TJF-260, Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Biliary cannulation was performed using a guidewire-assisted technique (0.025-inch guidewire; visiglide 2, Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan), after the catheter impacted with the papilla, with none of the cases included in our analysis treated using a primary needle knife fistulotomy. Prophylactic pancreatic stenting was attempted for patients who required ≥ 2 attempts at pancreatic duct cannulation or underwent pancreatic duct contrast injection. Endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed in all patients.

We surveyed the success rate of cannulation, cannulation time and total procedure time, and the occurrence and type of ERCP-related adverse events. Successful ERCP was defined by biliary cannulation completed in one ERCP session. Cannulation time was calculated from the initial examination of the orifice of the ampulla to bile duct cannulation. Total procedure time was calculated from the initial examination of the orifice of the ampulla to the end of the procedure. PEP occurrence was determined from the serum amylase and lipase levels, obtained before the procedure and on post-operative day 1. Abdominal radiographs were used to survey for perforation in patients with abdominal pain 4 h after the procedure. ERCP-related adverse events included bleeding, PEP, and perforation[12].

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software (version 22.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Categorical data were summarized by frequency and percentage, with between-group differences evaluated using the chi-squared test. Continuous data were summarized by the mean ± SD, with an independent t-test used to evaluate differences between the two groups. Univariate analyses were conducted to identify predictors of PEP. Factors with a P < 0.2 were included in a multivariate analysis, together with clinically meaningful variables, to identify independent predictors of PEP. Statistical significance was determined by a P < 0.05.

The baseline characteristics of the 293 cases are summarized in Table 1. After propensity score matching, 138 cases, 69 in each group, were included in the analysis, with the beginner and expert groups balanced on the variables of sex [18/69 (26.1%) vs 10/69 (14.5%), P = 0.090], diameter of the bile duct (9.4 mm vs 10.0 mm, P = 0.322) and ratio of benign disease [63/69 (91.3%) vs 64/69 (92.8%), P = 0.753].

| Before propensity matching | After propensity matching | |||||||

| Beginner (n = 97) | Expert (n = 196) | P value | D | Beginner (n = 69) | Expert (n = 69) | P value | D | |

| Female | 35 (36.1) | 104 (53.1) | 0.006 | 0.383 | 18 (26.1) | 10 (14.5) | 0.090 | 0.404 |

| Age | 69.8 ± 12.2 | 67.6± 12.3 | 0.143 | 0.179 | 71.8 ± 11.0 | 72.2 ± 10.7 | 0.790 | 0.037 |

| Angle | 29.5 ± 15.5 | 30.1 ± 16.1 | 0.752 | 0.038 | 29.6 ± 15.9 | 30.3 ± 16.4 | 0.789 | 0.043 |

| Angle > 30 (%) | 45 (46.4) | 96 (49.0) | 0.678 | 0.057 | 32 (46.4) | 33 (47.8) | 0.865 | 0.032 |

| Bile duct dilatation | 9.0 ± 3.3 | 8.2 ± 3.4 | 0.046 | 0.238 | 9.4 ± 3.3 | 10.0 ± 4.0 | 0.322 | 0.164 |

| Benign Dz | 78 (80.4) | 132 (67.3) | 0.019 | 0.380 | 63 (91.3) | 64 (92.8) | 0.753 | 0.109 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 30 (30.9) | 67 (34.2) | 0.579 | 0.082 | 24 (34.8) | 32 (46.4) | 0.165 | 0.267 |

| Erythema | 10 (10.3) | 26 (13.3) | 0.470 | 0.158 | 8 (11.6) | 11 (15.9) | 0.459 | 0.203 |

| Bulging | 5 (5.2) | 12 (6.1) | 0.740 | 0.101 | 2 (2.9) | 7 (10.1) | 0.085 | 0.733 |

Baseline patient characteristics for cases with an acute or obtuse distal CBD angle are reported in supplementary table 1. The distribution of acute and obtuse angles was not different between the beginner (37 acute and 32 obtuse) and expert (36 acute and 33 obtuse) group, but the mean acute and obtuse angle was different (P < 0.001) between the beginner (17.9º ± 7.8º and 43.1º ± 11.4º) and expert (18.9º ± 7.0º and 43.8º ± 12.7º) group. The diameter of the bile duct was not different between acute and obtuse angle cases for the beginner (P = 0.119) and expert (P = 0.270) group, and neither was the presence of erythema of the ampulla (beginner, P = 0.084; expert, P = 0.627). However, in the expert group, the ratio of bulging ampulla was greater in the obtuse (18.2%) than acute (2.8%) angle cases (P = 0.034), with no difference in the beginner group (P = 0.917).

Comparison of ERCP outcomes between the acute and obtuse distal CBD angle groups is reported in Table 2. For the beginner endoscopist, ERCP success rate was 94.6 % in the acute angle group and 100% in the obtuse group (P = 0.187). The cannulation time was 2.6 min longer in the acute than obtuse angle group (6.7 min ± 7.2 min vs 4.1 min ± 4.2 min, P = 0.076). The ratio of pancreatic duct cannulation or pancreatic duct contrast injection was higher in the acute (37.8%) than obtuse (25.0%) angle group, although this difference was not significant (P = 0.260). The rate of PEP was significantly higher in the acute (21.6%) than obtuse (3.1%) angle group (P = 0.023). The rates of other complications (bleeding and perforation) were not different between the acute and obtuse angle groups for the beginner endoscopist. For the expert endoscopist, the success rate was 100% in the acute angle group and 97% in the obtuse group (P = 0.293). The cannulation time was similar for the acute and obtuse angle groups (4.2 min ± 2.9 min vs 4.3 min ± 2.9 min, P = 0.833). The ratio of pancreatic duct cannulation or pancreatic duct contrast injection was higher in the acute (22.2%) than obtuse (12.1%) angle group, although this difference was not significant (P = 0.276). The rate of PEP was slightly higher in the obtuse (6.1%) than acute (2.8%) angle group, although this difference was not significant (P = 0.511). The rates of other complications (bleeding and perforation) were not different between the acute and obtuse angle groups for the expert endoscopist.

| Beginner endoscopist | Expert endoscopist | |||||||

| Total (n = 69) | Acute angle (n = 37) | Obtuse angle (n = 32) | P value | Total (n = 69) | Acute angle (n = 36) | Obtuse angle (n = 33) | P value | |

| Success rate | 67 (97.1) | 35 (94.6) | 32 (100) | 0.187 | 68 (98.6) | 36 (100) | 32 (97) | 0.293 |

| Cannulation time | 5.5 ± 6.0 | 6.7 ± 7.2 | 4.1 ± 4.2 | 0.076 | 4.3 ± 2.9 | 4.2 ± 2.9 | 4.3 ± 2.9 | 0.833 |

| Total procedure | 19.6 ± 10.3 | 20.7 ± 11.2 | 18.3 ± 9.2 | 0.330 | 17.7 ± 7.5 | 16.8 ± 4.4 | 18.8 ± 9.9 | 0.296 |

| P-duct insertion or injection | 22 (31.9) | 14 (37.8) | 8 (25.0) | 0.260 | 10 (17.4) | 6 (22.2) | 4 (12.1) | 0.276 |

| P-duct stent | 19 (27.5) | 12 (32.4) | 7 (21.9) | 0.335 | 7 (10.1) | 4 (11.1) | 3 (9.1) | 0.785 |

| PEP | 9 (13.0) | 8 (21.6) | 1 (3.1) | 0.023a | 3 (4.3) | 1 (2.8) | 2 (6.1) | 0.511 |

| Hyperamylase-mia | 12 (17.4) | 6 (16.2) | 6 (18.8) | 0.786 | 12 (17.4) | 6 (16.7) | 6 (18.2) | 0.868 |

| Bleeding | 2 (2.9) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (3.1) | 0.918 | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.0) | 0.293 |

| Perforation | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

And supplementary table 2 showed comparison of ERCP outcomes between the acute and obtuse distal CBD angle groups, about all of patients who were performed ERCP by beginner endoscopist. There was no significant difference between the two groups except for PEP, which is similar to the comparison in patients with propensity score matching. The rate of PEP was significantly higher in the acute (19.2%) than obtuse (4.5%) angle group (P = 0.030). There was one perforation in obtuse angle group, but there was no statistical significance.

Clinical factors associated with PEP for the beginner endoscopist are reported in Table 3. Among the 69 patients in this group with a naïve papilla and no signs of pancreatitis at admission, PEP developed in 9 cases after ERCP. On univariate analysis, an acute distal CBD angle (P = 0.023) was significantly associated to PEP incidence, and was retained as an independent predictive factor of PEP on multivariate analysis (P = 0.049). Other factors included in the multivariate analysis for the beginner endoscopist (female sex and pancreatic duct cannulation or contrast injection) were not significant predictors of PEP.

| Beginner endoscopist | |||||

| Total (n = 69) | With PEP (n = 9) | Without PEP (n = 60) | P value | ||

| Univariable | Multivari-able | ||||

| Age (yr) | 71.8 ± 11.0 | 73.0 ± 6.5 | 71.6 ± 11.5 | 0.718 | - |

| Female | 18 (26.1) | 4 (44.4) | 14 (23.3) | 0.184 | 0.182 |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 24 (34.8) | 3 (33.3) | 21 (35.0) | 0.923 | - |

| Erythema | 8 (11.6) | 1 (1.1) | 7 (11.7) | 0.865 | - |

| Buldging | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.3) | 0.585 | - |

| Malignancy | 6 (8.7) | 0 (0) | 6 (10.0) | 0.328 | - |

| Benign diseases | 63 (91.3) | 9 (100) | 54 (90.0) | - | - |

| Bile duct dilatation | 9.4 ± 3.3 | 9.4 ± 4.4 | 9.4 ± 3.2 | 0.937 | - |

| Acute angle | 37 (53.6) | 8 (88.9) | 29 (48.3) | 0.023a | 0.049a |

| Cannulation time (min) | 5.5 ± 6.0 | 6.8 ± 2.1 | 5.3 ± 6.4 | 0.534 | - |

| Total Procedure time (min) | 19.6 ± 10.3 | 17.3 ± 4.9 | 19.9 ± 10.9 | 0.492 | - |

| P-duct insertion or injection | 22 (31.9) | 5 (55.6) | 17 (28.3) | 0.105 | 0.181 |

| P-duct stent | 19 (27.5) | 3 (33.3) | 16 (26.7) | 0.682 | - |

Clinical factors associated with PEP over the entire study cohort are reported in Table 4. On univariate analysis, pancreatic duct cannulation or contrast injection (P = 0.002) was the only significant factor associated with PEP incidence. On multivariate analysis, female sex (P = 0.017) and pancreatic duct cannulation or contrast injection (P = 0.003) were retained as independent predictors of PEP. An acute distal CBD angle and the experience of the endoscopist did not predictors of PEP. Of note, cannulation time approached significance, with a longer time among PEP than non-PEP cases (6.7 min ± 2.2 min vs 4.8 min ± 4.9 min, P = 0.052).

| Total (n = 138) | With PEP (n = 12) | Without PEP (n = 126) | P value | ||

| Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

| Age (yr) | 72.0 ± 10.8 | 72.1 ± 7.0 | 72.0 ± 11.1 | 0.978 | - |

| Female | 28 (20.3) | 5 (41.7) | 23 (18.3) | 0.055 | 0.017a |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 56 (40.6) | 3 (25.0) | 53 (42.1) | 0.253 | - |

| Erythema | 19 (13.8) | 2 (16.7) | 17 (13.5) | 0.762 | - |

| Buldging | 9 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (7.1) | 0.342 | - |

| Malignancy | 11 (8.7) | 0 (0) | 11 (8.7) | 0.289 | - |

| Benign diseases | 127 (92.0) | 12 (100) | 115 (91.3) | - | - |

| Bile duct dilatation | 9.7 ± 3.7 | 9.8 ± 3.9 | 9.7 ± 3.7 | 0.941 | - |

| Acute angle | 73 (52.9) | 9 (75.0) | 64 (50.8) | 0.110 | 0.324 |

| Beginner endoscopist | 69 (50.0) | 9 (75.0) | 60 (47.6) | 0.071 | 0.743 |

| Cannulation time (min) | 5.0 ± 4.7 | 6.7 ± 2.2 | 4.8 ± 4.9 | 0.201 | 0.052 |

| Total Procedure time (min) | 18.7 ± 9.1 | 16.8 ± 4.9 | 18.8 ± 9.4 | 0.467 | - |

| P-duct insertion or injection | 32 (23.2) | 7 (58.3) | 25 (19.8) | 0.002a | 0.003a |

| P-duct stent | 27 (19.6) | 3 (25.0) | 24 (19.0) | 0.622 | - |

PEP is an adverse outcome of ERCP that is difficult to effectively manage and carries a risk of mortality. It is well accepted that intensive training and accumulation of experience with ERCP procedures for beginner endoscopists is essential. In this study, we further explored the possibility that risk factors for PEP might be different between a beginner and expert endoscopist. Only a few, small, studies have previously addressed the issue of endoscopist experience as a factor for PEP[9-11]. We identified an acute distal CBD angle as the only independent risk factor for PEP for the beginner endoscopist, with not predictive association between the distal CBD angle and PEP for the expert endoscopist. The distal CBD angle was not a predictive factor for other adverse events. No other predictive factors of ERCP-related adverse events were identified.

Different thresholds of practice have been suggested for beginner endoscopists. The American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends that > 180 ERCP procedures be completed[13]. However, considering inherent differences in ability between trainees, the number of procedures alone cannot determine the absolute learning curve. For this reason, some researchers have advocated for competence to be based on actual performance, such as the rate of successful cannulation, rather than a specific case volume[10,14]. In our study, the beginner endoscopist reached a rate of successful cannulation of 90% after completing 100 supervised ERCP procedures during training and observing about 500 procedures over a 1-year period. As beginner endoscopist generally perform ERCP under supervision, we argue that risk factors identified in previous studies, with supervision, do not represent factors that are unique to the beginner status of an endoscopist. In this regard, our study revealed an acute CBD angle to be a risk factor for PEP that is specific to the beginner status of an endoscopist. Consequently, we believe that most ERCP procedures can feasibly be performed by a beginner endoscopist without supervision with no expectation of additional risk, so long as there is adequate pre-procedure planning to avoid assigning cases with an acute distal CBD angle to a beginner in an effort to lower the incidence rate of PEP.

Overall, we identified female sex and pancreatic duct insertion or injection as important risk factors for PEP, which is consistent with previous studies. Women are at 50% higher risk for PEP then men[15,16]. As well, main pancreatic duct injection is associated with a 50% higher risk of PEP[16]. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy defines difficult cannulation, which might increase the risk for PEP, as > 5 contacts with the papilla, attempt at cannulation for > 5 min, and unintended pancreatic duct cannulation[17]. As our study used a retrospective analysis, the number of cannulation attempts was not consistently surveyed and, therefore, could not be entered as a variable in our analysis. Although not retained as a significant factor, for cases performed by the beginner endoscopist, pancreatic duct cannulation was performed slightly more frequently in the acute than obtuse distal CBD angle group, with the procedure time also being slightly longer in the acute angle group. From this point of view, cannulation might more difficult for acute than obtuse angles, with this difficulty being an issue for the beginner but not the expert endoscopist. For cases with an acute distal CBD angle, a higher proportion of pancreatic-duct cannulations was performed, although not significant. In the acute angle group, the CBD angle is more likely to be directed upward, relative to the bile duct, which would increase the risk of irritation of the pancreatic ducts, thus increasing the difficulty in entering the bile duct and the number of cannulation attempted before achieving deep cannulation (Figure 2). This might explain the higher risk for PEP associated with an acute than obtuse distal CBD angle. The lower rate of PEP in cases with an acute distal CBD angle for the expert than beginner endoscopist may reflect the higher skilled manipulation of the catheter by the expert, as well as the ability of the expert to more quickly switch to a rescue method. Therefore, the ability to quickly modify the procedure may be an added feature of expertise, in addition to manipulation skills. Supervision during these more difficult ERCP procedures could overcome lack of experience. Knowing the risk factors for PEP, and other adverse events, would be important for a more appropriate selection of cases when a beginner endoscopist begins unsupervised procedures.

In our study, the angle of the distal CBD was defined relative to a vertical line drawn from the lower wall of the bile duct in coronal view of CT images. The distal CBD angle can also be defined by the intersection of a line extending from the duodenum wall to a virtual median line through the bile ducts. However, identifying the wall of the duodenum may be difficult, making it difficult to reliably estimate the distal CBD angle, either by CT or magnetic resonance imaging. It is to address this limitation that we measured the distal CBD angle relative to a virtual vertical line extending to the lower wall of the bile duct. We hypothesized that the angle thus measured was related to the angle of the duodenum and the bile duct, thereby reflecting the entire distal angle. However, the measured angle can vary depending on where the distal reference point is located. As an example, an enlarged bile duct may appear to be at a more obtuse angle than it actually is. However, we do note that in our analysis, the diameter of the bile duct was not statistically associated to the angle. Therefore, use of the lower wall of the bile duct may provide an alternative to the use of a median bile duct reference line.

The limitations of our study should be acknowledged. First, because of the retrospective design of our study, a selection bias cannot be denied. Moreover, baseline characteristics were different between the beginner and expert group, requiring propensity score matching to correct this heterogeneity. Second, our sample size was relatively small, and ERCP procedures were performed by one beginner and one expert endoscopist. Although this approach was sufficient to identify an acute distal CBD angle as a specific risk factor for PEP for the beginner but not expert endoscopist, a larger sample of endoscopists is needed to confirm our results. Third, the PEP rate for our beginner endoscopist was higher than previously reported. This might reflect the fact that this was the first ERCP procedures performed by the beginner endoscopist without supervision. We recognize this as a disadvantage of our study design.

In conclusion, an acute distal CBD angle is a risk factor for PEP for the beginner but not expert endoscopist. As the distal CBD angle can be verified on CT images before ERCP, it would be possible to avoid allocating cases with an acute distal CBD angle to a beginner endoscopist, particularly for those first performing ERCP without supervision. Supervision for beginner endoscopist performing ERCP in patients with an acute distal CBD angle might be appropriate to assist with the difficult upward manipulation of the catheter and early consideration of a rescue method. Further studies are needed to confirm our findings.

The risk factor for post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) pancreatitis (PEP) in beginner endoscopist is not well-known.

It is hypothesized that there will be structural risk factors that can be known before the procedure.

In this study, the authors aimed to determine whether the difference in distal common bile duct (CBD) angle was associated with PEP.

The authors performed analysis after propensity-score matching to compare the patient who underwent ERCP by different experiences endoscopists.

The authors found significant correlation between acute distal CBD angle and PEP in beginner endoscopist.

These findings suggest that acute distal CBD angle is a risk factor for PEP in beginner endoscopist.

We should pay more attention to perform the ERCP in patient with acute distal CBD angle by beginner endoscopist. And it is better to perform the ERCP by expertised endoscopist or to be with supervisor.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rodrigo L S-Editor: Wang YQ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Chandrasekhara V, Khashab MA, Muthusamy VR, Acosta RD, Agrawal D, Bruining DH, Eloubeidi MA, Fanelli RD, Faulx AL, Gurudu SR, Kothari S, Lightdale JR, Qumseya BJ, Shaukat A, Wang A, Wani SB, Yang J, DeWitt JM. Adverse events associated with ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:32-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 66.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dumonceau JM, Andriulli A, Elmunzer BJ, Mariani A, Meister T, Deviere J, Marek T, Baron TH, Hassan C, Testoni PA, Kapral C; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - updated June 2014. Endoscopy. 2014;46:799-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 36.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kochar B, Akshintala VS, Afghani E, Elmunzer BJ, Kim KJ, Lennon AM, Khashab MA, Kalloo AN, Singh VK. Incidence, severity, and mortality of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review by using randomized, controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:143-149.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Domagk D, Oppong KW, Aabakken L, Czakó L, Gyökeres T, Manes G, Meier P, Poley JW, Ponchon T, Tringali A, Bellisario C, Minozzi S, Senore C, Bennett C, Bretthauer M, Hassan C, Kaminski MF, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Rees CJ, Spada C, Valori R, Bisschops R, Rutter MD. Performance measures for ERCP and endoscopic ultrasound: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Quality Improvement Initiative. Endoscopy. 2018;50:1116-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Morales SJ, Sampath K, Gardner TB. A Review of Prevention of Post-ERCP Pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2018;14:286-292. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Tarnasky PR, Palesch YY, Cunningham JT, Mauldin PD, Cotton PB, Hawes RH. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1518-1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fogel EL, Eversman D, Jamidar P, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: pancreaticobiliary sphincterotomy with pancreatic stent placement has a lower rate of pancreatitis than biliary sphincterotomy alone. Endoscopy. 2002;34:280-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Elmunzer BJ, Scheiman JM, Lehman GA, Chak A, Mosler P, Higgins PD, Hayward RA, Romagnuolo J, Elta GH, Sherman S, Waljee AK, Repaka A, Atkinson MR, Cote GA, Kwon RS, McHenry L, Piraka CR, Wamsteker EJ, Watkins JL, Korsnes SJ, Schmidt SE, Turner SM, Nicholson S, Fogel EL; U. S. Cooperative for Outcomes Research in Endoscopy (USCORE). A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1414-1422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 503] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Testoni PA, Mariani A, Giussani A, Vailati C, Masci E, Macarri G, Ghezzo L, Familiari L, Giardullo N, Mutignani M, Lombardi G, Talamini G, Spadaccini A, Briglia R, Piazzi L; SEIFRED Group. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis in high- and low-volume centers and among expert and non-expert operators: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1753-1761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ekkelenkamp VE, Koch AD, Rauws EA, Borsboom GJ, de Man RA, Kuipers EJ. Competence development in ERCP: the learning curve of novice trainees. Endoscopy. 2014;46:949-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vandervoort J, Soetikno RM, Tham TC, Wong RC, Ferrari AP, Montes H, Roston AD, Slivka A, Lichtenstein DR, Ruymann FW, Van Dam J, Hughes M, Carr-Locke DL. Risk factors for complications after performance of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:652-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2036] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Chutkan RK, Ahmad AS, Cohen J, Cruz-Correa MR, Desilets DJ, Dominitz JA, Dunkin BJ, Kantsevoy SV, McHenry L, Mishra G, Perdue D, Petrini JL, Pfau PR, Savides TJ, Telford JJ, Vargo JJ; ERCP Core Curriculum prepared by the ASGE Training Committee. ERCP core curriculum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:361-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wani S, Hall M, Wang AY, DiMaio CJ, Muthusamy VR, Keswani RN, Brauer BC, Easler JJ, Yen RD, El Hajj I, Fukami N, Ghassemi KF, Gonzalez S, Hosford L, Hollander TG, Wilson R, Kushnir VM, Ahmad J, Murad F, Prabhu A, Watson RR, Strand DS, Amateau SK, Attwell A, Shah RJ, Early D, Edmundowicz SA, Mullady D. Variation in learning curves and competence for ERCP among advanced endoscopy trainees by using cumulative sum analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:711-9.e11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen JJ, Wang XM, Liu XQ, Li W, Dong M, Suo ZW, Ding P, Li Y. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a systematic review of clinical trials with a large sample size in the past 10 years. Eur J Med Res. 2014;19:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ding X, Zhang F, Wang Y. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon. 2015;13:218-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Testoni PA, Mariani A, Aabakken L, Arvanitakis M, Bories E, Costamagna G, Devière J, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Dumonceau JM, Giovannini M, Gyokeres T, Hafner M, Halttunen J, Hassan C, Lopes L, Papanikolaou IS, Tham TC, Tringali A, van Hooft J, Williams EJ. Papillary cannulation and sphincterotomy techniques at ERCP: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2016;48:657-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |