Published online Jan 6, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i1.157

Peer-review started: October 4, 2019

First decision: October 23, 2019

Revised: October 31, 2019

Accepted: November 15, 2019

Article in press: November 15, 2019

Published online: January 6, 2020

Processing time: 94 Days and 15 Hours

Isolated gastrointestinal venous malformations (GIVMs) are extremely rare congenital developmental abnormalities of the venous vasculature. Because of their asymptomatic nature, the diagnosis is often quite challenging. However, as symptomatic GIVMs have nonspecific clinical manifestations, misdiagnosis is very common. Here, we report a case of isolated diffuse GIVMs inducing mechanical intestinal obstruction. A literature review was also conducted to summarize clinical features, diagnostic points, treatment selections and differential diagnosis in order that doctors may have a comprehensive understanding of this disease.

A 50-year-old man presented with recurrent painless gastrointestinal bleeding for two months and failure to pass flatus and defecate with nausea and vomiting for ten days. Digital rectal examination found bright red blood and soft nodular masses 3 cm above the anal verge. Computed tomography showed that part of the descending colon and rectosigmoid colon was thickened with phleboliths in the intestinal wall. Colonoscopy exhibited bluish and reddish multinodular submucosal masses and flat submucosal serpentine vessels. Endoscopic ultrasonography showed anechoic cystic spaces within intestinal wall. The lesions were initially thought to be isolated VMs involving part of the descending colon and rectosigmoid colon. Laparoscopic subtotal proctocolectomy, pull-through transection and coloanal anastomosis and ileostomy were performed. Histopathology revealed intact mucosa and dilated, thin-walled blood vessels in the submucosa, muscularis, and serosa involving the entire colorectum. The patient recovered with complete symptomatic relief during the 52-mo follow-up period.

The diagnosis of isolated GIVMs is challenging. The information presented here is significant for the diagnosis and management of symptoms.

Core tip: Few cases of gastrointestinal venous malformations (GIVMs) responsible for intestinal obstruction in adults have been described. We present a rare case of isolated GIVMs involving the colorectum in a patient with symptoms of intestinal obstruction. Digital rectal examination, enhanced computed tomography, colonoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography, barium contrast examination and selective mesenteric angiography contributed to a precise diagnosis. Laparoscopic subtotal proctocolectomy, pull-through transection and coloanal anastomosis were performed. The patient did not develop any serious complications during the follow-up period. We have also summarized the information obtained from 152 cases reported to date, which is important in assisting physicians with the diagnosis and treatment.

- Citation: Li HB, Lv JF, Lu N, Lv ZS. Mechanical intestinal obstruction due to isolated diffuse venous malformations in the gastrointestinal tract: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(1): 157-167

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i1/157.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i1.157

Vascular malformations, the result of inborn errors in vascular morphogenesis, are further classified on the basis of the main vessel type (capillary, venous, lymphatic, and arterial) and combined malformations[1]. Among the different types, venous malformations (VMs), structural anomalies of the venous vasculature, are the most common type in the gastrointestinal (GI) system and can occur throughout the GI tract. These malformations may also involve extra-intestinal areas and adjacent organs such as the liver, spleen, and bladder[2]. As VMs are rare in the GI tract, little is known about them. The incidence rate of VMs is difficult to determine because of their asymptomatic nature. Symptomatic vascular malformations are found in 1 out of every 10000 individuals[3] and are usually seen in teenagers. As symptomatic VMs in the GI (GIVMs) may cause occult or massive GI bleeding that is nonspecific, misdiagnosis is very common. Many patients undergo unnecessary pharmaceutical treatment for many years before the correct diagnosis is made, and some patients even undergo one or more surgeries[4]. Very few cases of GIVMs responsible for mechanical intestinal obstruction in adults have been described in the literature. We here describe a rare case of isolated VMs involving the total colorectum which remained asymptomatic and without anemia until adulthood when the patient developed symptoms of mechanical intestinal obstruction preoperatively.

A 50-year-old man presented to our general surgery department with recurrent painless GI bleeding for two months, and failure to pass flatus and defecate with nausea and vomiting for 10 d.

Two months previously, no obvious symptoms were present before the first rectal bleeding which coated the outside of the stool, stool frequency was 5-6 times a day and self-limited in nature. The patient did not seek medical attention during the course of bleeding. Ten days before the current admission, the patient suddenly stopped passing flatus and defecating without abdominal pain and anal pain, and started to vomit.

Unremarkable.

The patient had no family history of GIVMs.

Physical examination revealed minimal abdominal distension and bowel hyperactivity. No evidence of mucocutaneous vascular lesions was observed. Digital rectal examination found bright red blood and several soft nodular masses 3 cm above the anal verge. The rest of the examinations were unremarkable.

Laboratory parameters revealed mild anemia (hemoglobin 110 g/L) with a mean corpuscular volume of 88 fL and normal white blood cell and platelet counts.

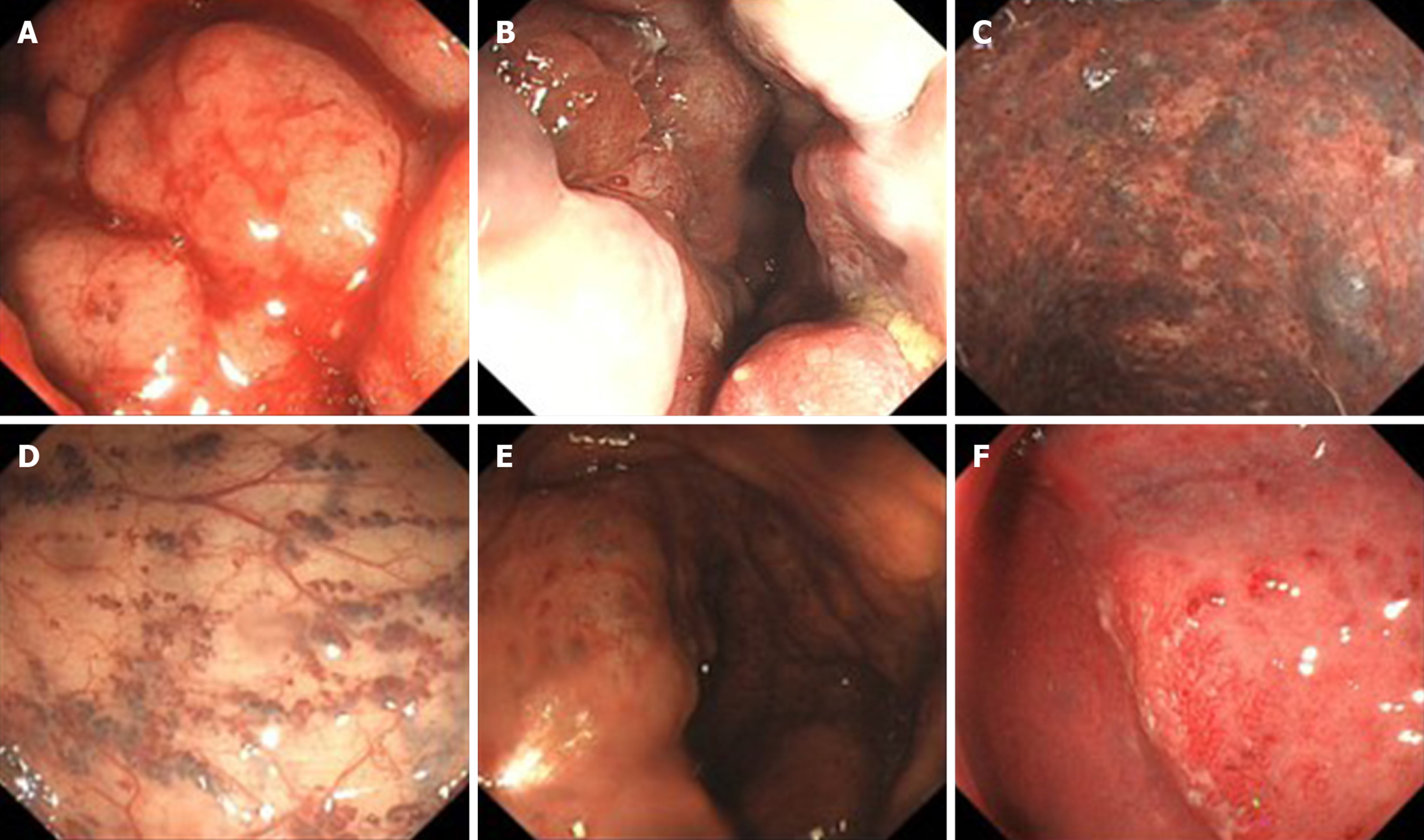

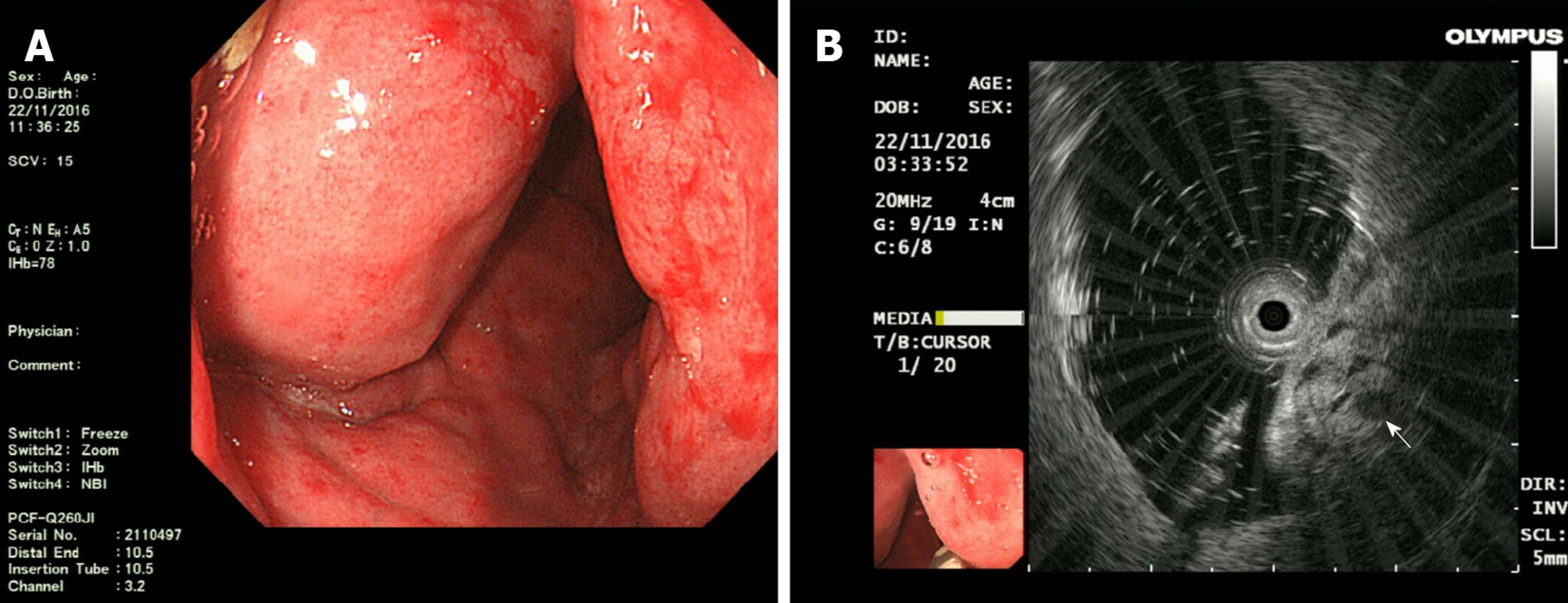

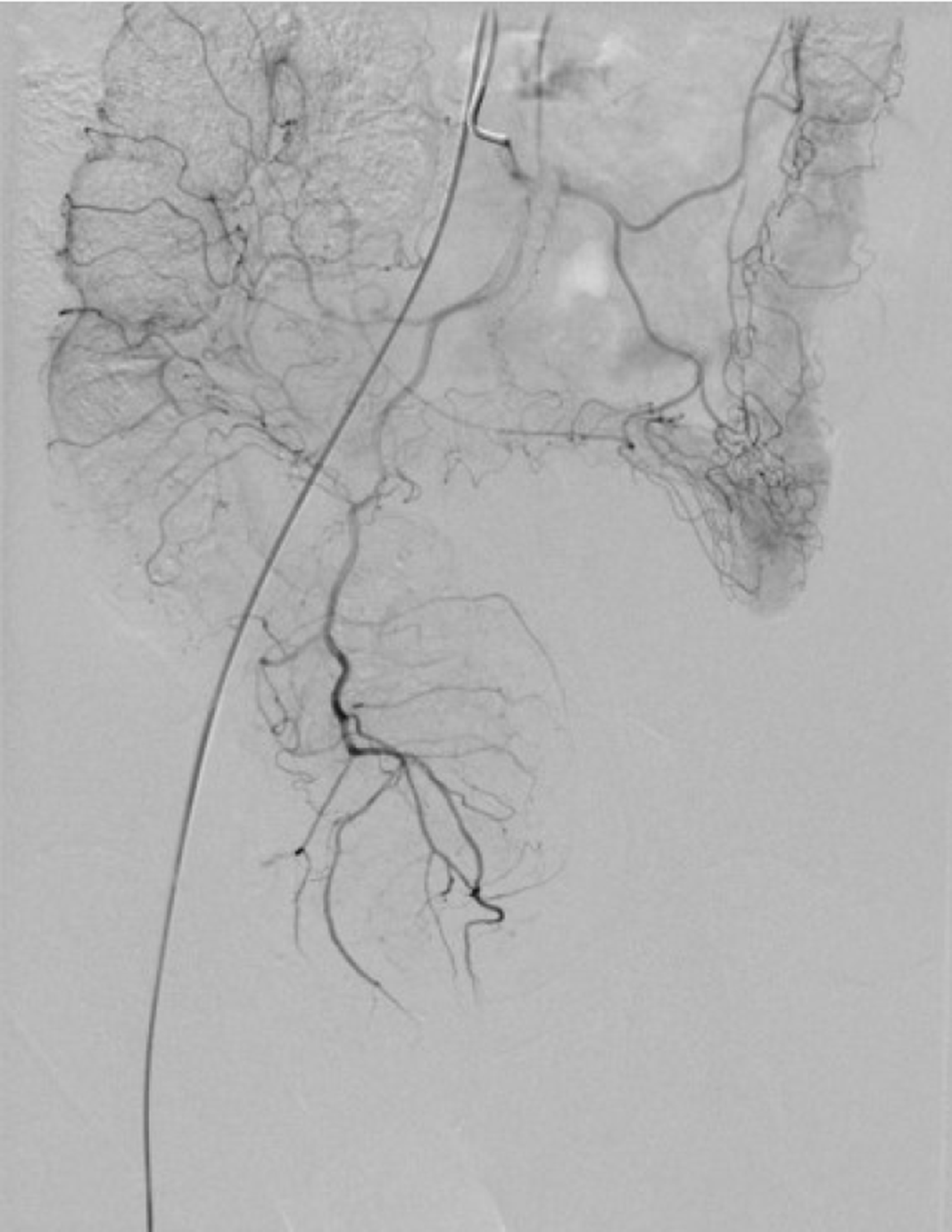

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed that part of the descending colon and rectosigmoid colon were thickened with edema, and numerous tiny dense spots considered to be phleboliths were distributed within the intestinal wall (Figure 1). At colonoscopy, bluish and reddish multinodular submucosal masses were seen occupying the entire rectosigmoid colon extending to the pectinate line (Figure 2A and B). Another typical positive finding was flat submucosal serpentine vessels (Figure 2C), which appeared as a sporadic lamellar submucosal lesion (Figure 2D) occupying part of the descending colon. Swelling of the intestinal mucosa, erosion, bleeding and an ischemic appearance were also identified when the supply vessels were obstructed by multiple thrombi (Figure 2E and F). In an evaluation of the bowel wall, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) showed distinct edema with erosion and redness in the intestinal mucosa (Figure 3A), with significant bowel wall thickening > 15 mm (especially the submucosa). The circumferential wall also revealed multiple small “anechoic cystic spaces” on EUS (Figure 3B). Selective mesenteric angiography showed that superior rectal artery was normal and only part of the descending colon and rectosigmoid colon was thickened (Figure 4). Barium contrast examination showed irregular rectal contours and indentation. Multidetector CT angiography of the mesenteric vessels was performed but no vascular abnormalities were found. Gastroscopy and capsule endoscopy were performed, and biopsy samples were taken to exclude the presence of other GI lesions. No other organs were involved.

Isolated GIVMs involving part of the descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum was the primary diagnostic consideration according to the imaging examinations.

Isolated GIVMs involving the entire colorectum.

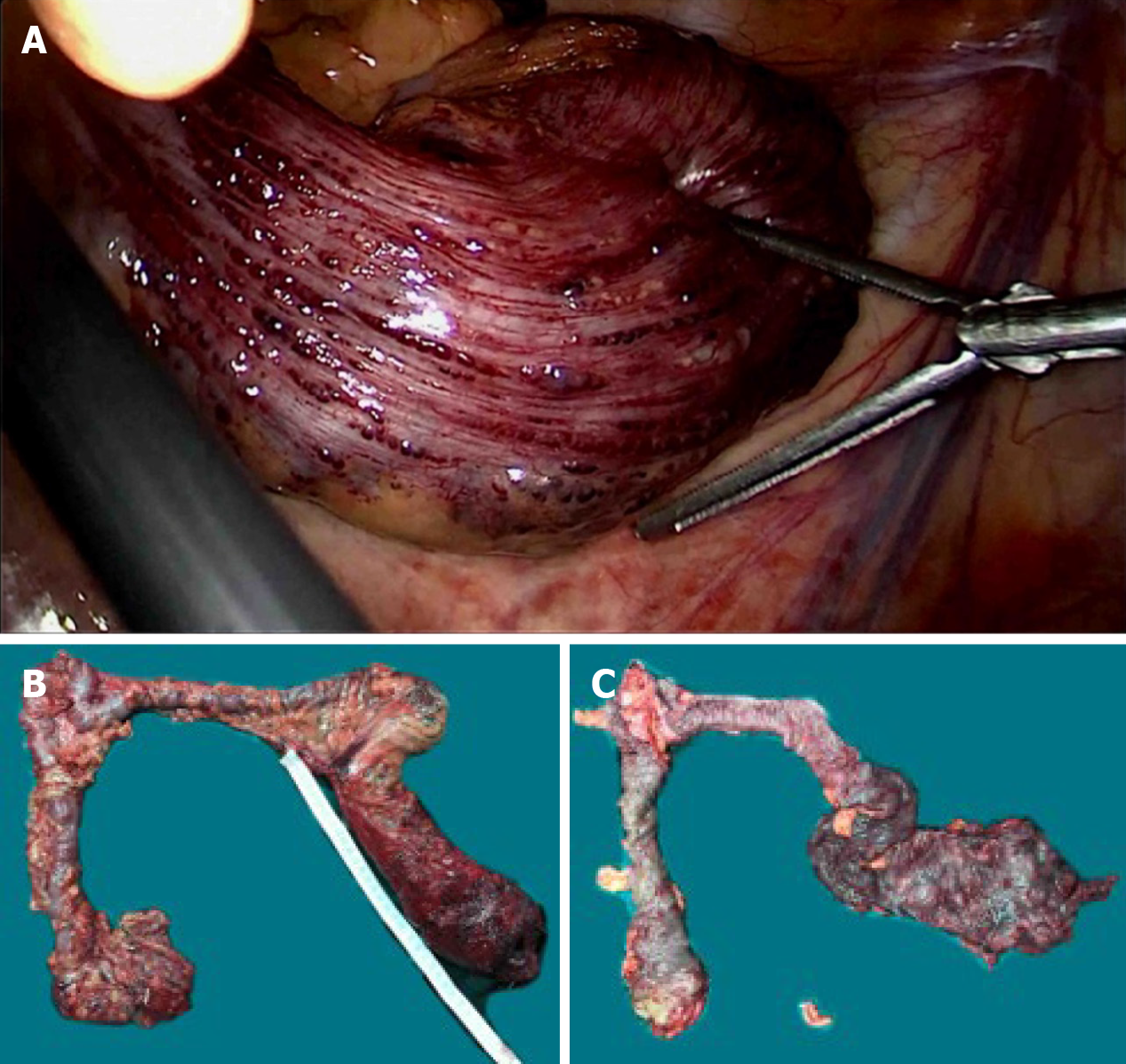

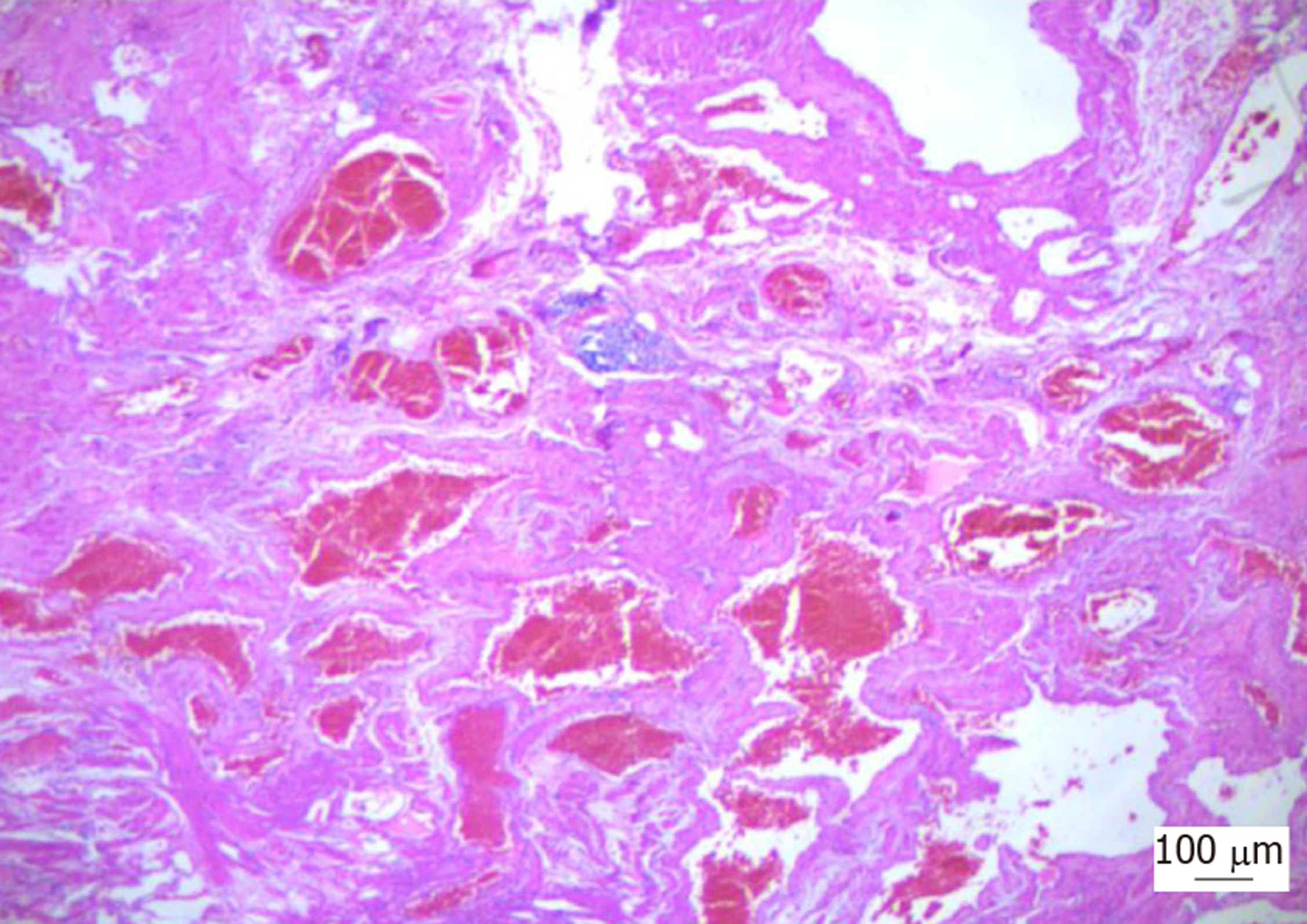

Based on the symptoms of intestinal obstruction, endoscopic findings and imaging examination results, we suggested a total proctocolectomy and abdominoperineal resection. However, this intervention was ruled out by the patient because of his fear of permanent ileostomy. We then considered performing laparoscopic total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (TPC-IPAA). Before the operation, the patient was managed conservatively with daily iron replacement and transfusions. However, at laparoscopy, vascular exophytic excrescences spread diffusely along the serosal surface of part of the thickened descending colon and rectosigmoid colon (Figure 5A) and the other part of the colon appeared to be normal. Considering the complications of TPC-IPAA and poor life quality of the patient, subtotal proctocolectomy, pull-through transection and coloanal anastomosis were performed finally. Ileostomy was performed to prevent postoperative anastomotic leakage due to the patient’s complete intestinal obstruction. Two units of red blood cells and 750 mL of fresh-frozen plasma were transfused. The surgical specimen was approximately 80 cm. On gross examination, an extensive network of vascular lakes was found which involved the wall of the descending colon and rectosigmoid colon infiltrating the surrounding connective tissue (Figure 5B) and bluish-greyish mucosa and a network of depressions on the surface in the areas of the emptied vascular lakes (Figure 5C). Microscopic examination revealed intact mucosa and accumulation of an increased amount of dilated, thin-walled blood vessels in the submucosa, muscular layer, and serosa involving the entire colorectum (Figure 6). The patient had a smooth postoperative recovery without bleeding or abdominal pain. Six months after hospital discharge, the patient underwent ileostomy closure surgery in our general surgery department. He was discharged in a stable condition two weeks later.

The follow-up period was 52 mo. Infection and anal stenosis did not occur in this case. For the first year after surgery, the patient defecated more than four times a day. In the second year after surgery, fecal frequency was satisfactory. The patient did not complain of intermittent rectal bleeding.

According to the 2014 and 2018 ISSVA classification, the use of the term “hemangioma” is inaccurate, with outdated terminology “cavernous hemangioma”[5]. Patients are being given the wrong treatment and wrong prognosis prediction for a vascular anomaly due to the misperceptions of terminology[6]. As a result, Kadlub et al[7] suggested that only the ISSVA classifications (approved at the 20th ISSVA Workshop, Melbourne, April 2014, late revision May 2018)[1] should be used to describe vascular anomalies instead of the WHO classification. According to that, “cavernous hemangioma” refers to “venous malformation”, a subtype of vascular malformations. Consequently, we use GIVMs instead of diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the GI tract.

A comprehensive search of electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, and the Web of Science) was performed to identify studies using MeSH terms and keywords such as “cavernous hemangioma”, “hemangiomatosis”, “venous malformation”, “stomach”, “gastric”, “small intestine”, “duodenum”, “jejunum”, “ileum”, “appendix”, “colon”, “rectum”, “anal canal” and “large intestine”, and 152 cases of isolated GIVMs were retrieved and reviewed.

According to our review of the literature, 18% of patients with isolated GIVMs were from China (27 cases), 12% from the USA (18 cases), 11% from Japan (17 cases), 9% from France (13 cases) and 5% from India (8 cases). The number of cases from other countries was much lower, which indicated that this disease can occur in multiple races.

The female-male ratio was approximately 1:1, indicating that there is no sex difference in isolated GIVMs. Among the patients reviewed (mean age, 38.6 years), 13% had GIVMs from childhood, 5% started GIVMs during adolescence, and 82% developed GIVMs in adulthood. Onset of the disease can occur at any age, but usually presents in young people. According to our review, they may occur anywhere along the intestinal system, and involved the stomach (9 cases), duodenum (2 cases), jejunum (22 cases), ileum (17 cases), appendix and cecum (2 cases), ascending colon (5 cases), transverse colon (6 cases), descending colon (5 cases), sigmoid (42 cases), rectum (84 cases) and anal canal (10 cases). The most commonly involved site in the small intestine was the jejunum, as reported by Durer et al[8]. The rectosigmoid was the most common site in the large intestine, as reported by Andrade et al[9]. Isolated GIVM lesions can be focal, multifocal, or diffuse. VMs of the mesentery has also been reported[10]. There is no sufficient evidence to show that the size and number of lesions increase with time.

The pathogenesis of GIVMs is uncertain. A pathological study showed that enlargement occurred by the projection of budding endothelial cells. However, whether these transformations are neoplastic or congenital is controversial. VMs represent developmental anomalies arising during the process of embryologic vasculogenesis; however, many patients remain asymptomatic until later in life. Isolated GIVMs are generally manifested as self-limited painless GI bleeding as the primary symptoms, leading to a diagnostic dilemma. Other symptoms include abdominal pain, intestinal obstruction, intussusceptions and volvulus. There are a number of possible explanations for the findings that the isolated GIVM lesions contributed to intestinal obstruction in our case. Endoscopy showing multiple bluish submucosal serpentine vessels and severe vascular congestion with the thickness of GI wall occupying the gut lumen may explain the clinical presentation of intestinal obstruction. In addition, the edema of GI wall which results in inadequate oxygenation to a segment of intestine, failure of intestinal movement, ischemia and eventually stenosis of the bowel may also explain the intestinal obstruction. Isolated VMs in the stomach are also manifested as dyspepsia. VMs of the appendix may cause intraperitoneal bleeding because of rupture of the appendix. Some forms of presentation are due to possible compression or invasion of adjacent structures, such as metrorrhagia, hematuria or perianal pain.

GI tract wall thickening with spotting atypical pelvic phleboliths with or without inflammation can be detected by CT[11]. However, when the extent of the lesions is limited, with no phleboliths, GI tract wall thickening might not be specific enough to be diagnosed by CT. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is superior to CT as it can help accurately evaluate the extent of the lesion and display the possible involvement of other organs, although MRI is not sensitive for focal calcification. The GI wall is markedly thickened (nodular or uniform) which is hypointense on Tl-weighted image and has a high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Signal intensity of adipose tissue around the intestinal wall is high on T2-weighted images and contains serpiginous structures representing small vessels in VMs. Five separate layers of the thickened rectal wall can be demonstrated by MRI with an endorectal surface coil. However, some authors[12] believe that CT is the most useful imaging method for establishing a diagnosis of VMs in the stomach.

GI endoscopy is the most important diagnostic method, and mucosal resection, argon plasma coagulation, laser photocoagulation, sclerotherapy or band ligation are necessary[13]. GI endoscopy can determine the location, morphology and the length of the involved segment, and can present a typical image of multiple bluish submucosal serpentine vessels with severe vascular congestion in the GI wall. Occasionally, enteritis and an ischemic appearance (congestion, swelling, and erosion) emerge instead of the characteristic endoscopic appearance. For this reason, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and severe anemia, repeated GI endoscopies are recommended. It should be noted that colonoscopy may not contribute to the diagnosis of VMs in the appendix as the examination can only reveal the appendiceal orifice[14]. Capsule endoscopy, double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE), CT enterography, and MR enterography are beneficial in preoperative diagnosis of VMs in the small intestine. According to the guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association in 2007 and the American College of Gastroenterology clinical guideline in 2015, the initial examination should be capsule endoscopy which is noninvasive and is recommended when identifying the source of bleeding. When positive findings are acquired, DBE should be performed[15], which provides both therapeutic and diagnostic interventions[9]. Endoscopic biopsy is not recommended due to the high risk of severe hemorrhage. However, Coumbaras et al[16], reported that they obtained a biopsy from a small rectal hemangioma without hemorrhage. EUS can reveal the five separate layers of the GI wall and sphincter muscles, which helps in the assessment of the extent of invasion into the anal canal. The presence of heterogeneous hypoechoic lesions, containing anechoic and hyperechoic areas, are limited by the muscularis propria. Phleboliths are also identified as calcific foci with shadow located within the GI wall. The lesion had pulsatile flow on the Doppler examination and was supplied by a small extraluminal vessel[9]. In pregnancy, EUS may be the imaging modality of choice[17].

Selective arteriography, which shows normal findings in most patients, is not necessary. However, Wu et al[18] found that selective inferior mesenteric angiography was beneficial in visualizing VM lesions in the rectum and identifying a vessel for embolization.

Barium contrast examination is of little importance in the diagnosis and shows poorly specific signs such as obstructing lesions or large polypoids. However, this examination helps to evaluate the extent of the lesion.

In patients with an acute onset, plain abdominal radiography is useful for intestinal obstruction and perforation, and abdominal ultrasonography is useful for intussusception and volvulus.

Some authors[4] suggested that radionuclide studies, particularly Tc–99 scans, may be conducive to the assessment of the extension of these lesions. Positron emission tomography may also be necessary as it is helpful for benign/malignant differentiation of the mass[12]. CT colonography also offers key diagnostic information in mucosal lesions and the intraluminal characteristics of submucosal lesions can be evaluated more easily[19].

In patients who have VMs in the rectum, digital rectal examination is performed to identify soft nodular compressible masses. During this process, the presence of multiple solid granular nodules indicates phleboliths.

Treatment can range from strict clinical follow-up, endoscopic sclerosis to surgical resection. According to our review, the treatment of isolated GIVMs included surgery [(laparoscopic surgery, 52 cases, 34%) and open surgery (80 cases, 53%)], conservative treatment (2 cases, 1%) and endoscopic treatment (10 cases, 7%), and eradication of the lesion is recommended.

Isolated GIVMs range from single polypoid lesions to large diffuse lesions. Most endoscopic resections for isolated GIVMs are performed for pedunculated lesions by polypectomy. For sessile polypoid type, endoscopic mucosal resection can be used. In cases of acute or difficult-to-manage bleeding, sclerosis of the lesions via endoscopy and fulguration with an argon laser have been carried out[20]. However, it should be noted that these strategies have limited value only in small, well-defined, solitary lesions located in the mucosa and submucosa. If the lesions are not completely removed, hematochezia continues or may even be aggravated postoperatively. For some patients[21] who received superselective angiography of the internal iliac vessel branches followed by permanent embolization with polyvinyl alcohol particles, the frequency and amount of rectal bleeding were significantly decreased. Future studies are needed to determine the indications for endoscopic treatment.

It is clear that surgical resection is the first choice of treatment for large or diffuse lesions. Segmental resection of the GI tract has been performed. For isolated VMs in the stomach, wedge resection, and partial or total gastrectomy are the standard treatments. For VMs involving the rectum, anterior resection is not recommended as it is impossible to completely remove the lesions which originate from the dentate line[22]. Instead, abdominal-perineal amputation, sphincter mucosectomy and pull-through coloanal sleeve anastomosis, and pull-through transection and coloanal anastomosis are frequently performed[23,24]. When the tumor has extended to the anal canal, abdominoperitoneal resection is performed, whereas a permanent stoma and multiple complications are the main disadvantages. In order to avoid these complications, an endorectal pull-through operation[25] and resection of the entire involved segment should be performed, and sclerotherapy to treat a small amount of remaining hemangioma[26] provides a good result without damaging the rectal sphincter mechanism. Furthermore, coloanal sleeve anastomosis was proposed by Jeffery et al[23]. Although this surgery does not remove the entire lesion, hemorrhage is relieved as the engorged friable mucosa and submucosa of the rectum are removed. However, one disadvantage of this surgery is that a wide mucosectomy is a difficult procedure, although it has been reported that a short muscular rectal cuff (3-4 cm) is sufficient[27,28]. Another disadvantage is that recurrence of hemorrhage may occur as the muscular layer and serosa of the muscular rectal cuff may invade the inner colon[4]. Pull-through transection and coloanal anastomosis ensure the complete resection of VMs involving the rectum without permanent colostomy. During the procedure, the rectum can be liberated to the level of the levator ani muscle, and then the rectum is pulled out of the anus and is cut on the dentate line. The resection is more precise as it is carried out under direct vision. A temporary diverting ileostomy or colostomy contributes to preventing postoperative anastomotic leakage. Continence to flatus and stool can be improved by an ileal or colonic J-pouch[22]. Furthermore, some authors[27] adopted a two-stage operation. The first stage is a sigmoid double-barrel colostomy which can improve anal bleeding and reduce the size of engorged vessels and fibrosis, which makes it easier to perform the second stage. Laparoscopic surgery and 3-D laparoscopy-assisted bowel resection have been shown to be useful for both diagnosis and treatment[14,29]. During surgery, a purple-colored nodular or granular lesion that was raspberry-like in appearance was observed.

Wu et al[18] presented a case of transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) surgery for VMs of the rectum. Zeng et al[30] showed that transanal endoscopic surgery (TAES) is safe and feasible for curing VMs involving the rectum. However, the feasibility and safety of TaTME and TAES for GIVMs needs to be evaluated in a large number of patients. A single-port device introduced through a trans-umbilical incision was successfully performed in patients who had VMs of the small bowel[31].

It is essential to define the relationship between the lesion and the sphincter to determine sphincter preservation[4]. If hemorrhage can be controlled and there is no evidence of malignant change, sphincter-saving procedures are recommended. Furthermore, in some cases[32], it has been shown that rectal cancer can develop in the setting of VMs in the rectosigmoid colon.

When associated complications occur (difficult-to-control bleeding, perforation, intussusceptions, or volvulus), emergency surgery is required. Sometimes acute clinical condition does not allow establishment of the diagnosis preoperatively. Consequently, it is important to know how to identify GIVMs macroscopically to determine how to proceed.

There are no reports on successful drug treatment of isolated GIVMs. However, a significant decrease in the size of GIVMs can be achieved following propranolol treatment[33]. Hormonal therapy (ethinylestradiol plus norethisterone) did not demonstrate any superiority compared to placebo[34]. The antiangiogenic drug, thalidomide, showed higher efficacy in reducing rebleeding and transfusion requirements than placebo in angiodysplasia; however, its use induced significant drug-related side effects[35]. Iannone et al[36] conducted a review and found that octreotide may be effective and safe for GI bleeding due to angiodysplasia. Studies are needed to confirm the results of drug efficacy, in order to provide physicians with a treatment option for patients without available alternatives.

The prognosis of GIVMs depends on permanent sphincter lesions and incomplete GIVMs removal. Immunodeficiency secondary to GIVMs in some cases improved following surgical correction of the GI abnormalities[37].

Isolated GIVMs should be differentiated from other hemorrhagic VMs, such as blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS)[38], Cowden syndrome (CS)[39], and Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome (KTS)[40]. GI BRBNS may appear in any site from the mouth to the anus, but can also cause other cutaneous lesions. It may be inherited by an autosomal dominant pattern. Soblet et al[41] found that BRBNS was caused by somatic mutations in the endothelial cell-specific tyrosine kinase receptor TIE2/TEK. As a result, patients with GIVMs but without lesions in other organs should be considered to have this syndrome only if they have a family history or gene mutations. CS is caused by gene mutation of PTEN. Multiple VMs in the small intestine may be characteristic findings in patients with CS[39]. KTS is characterized by a triad of port wine nevi, bony or soft tissue hypertrophy of an extremity (localized gigantism) and varicose veins or VMs of unusual distribution[40]. Moreover, for VMs in the stomach, due to frequent submucosal localization, other gastric submucosal masses, such as GI stromal tumors, leiomyomas and lipomas should be considered in the differential diagnosis[12]. VMs in the rectum are often misinterpreted as rectal varicosis of portal hypertension[39]. Rectal varicosis without the typical findings of hepatic cirrhosis should be a focus of attention as it may be an indication of VMs in the rectum. Positive findings on digital rectal examination can distinguish between VMs in the rectum and hemorrhoids.

Isolated GIVMs are extremely rare congenital developmental abnormalities of the venous vasculature. According to our review of the literature, this disease can occur in multiple races. There is no sex difference in isolated GIVMs. The most commonly involved site in the small intestine was the jejunum. The rectosigmoid was the most common site in the large intestine. The lesions can be focal, multifocal, or diffuse. Self-limited painless GI bleeding is always the primary symptoms. Physical examination, CT, CT enterography, MRI, MR enterography, digestive endoscopy, capsule endoscopy, DBE, EUS, barium contrast examination, radionuclide studies, positron emission tomography and selective mesenteric angiography contributed to a precise diagnosis. Treatment can range from strict clinical follow-up, endoscopic sclerosis to surgical resection. Eradication of the lesion is recommended.

We thank the Institute of Pathology, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital, for providing histopathology photographs.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tsoulfas G S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: MedE Ma JY E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies. Available from: https://www.issva.org/classification. |

| 2. | Topalak O, Gönen C, Obuz F, Seçil M. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectosigmoid colon with extraintestinal involvement. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2006;17:308-312. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Gordon FH, Watkinson A, Hodgson H. Vascular malformations of the gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;15:41-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hervías D, Turrión JP, Herrera M, Navajas León J, Pajares Villarroya R, Manceñido N, Castillo P, Segura JM. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum: an atypical cause of rectal bleeding. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2004;96:346-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Steele L, Zbeidy S, Thomson J, Flohr C. How is the term haemangioma used in the literature? An evaluation against the revised ISSVA classification. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:628-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hassanein AH, Mulliken JB, Fishman SJ, Greene AK. Evaluation of terminology for vascular anomalies in current literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:347-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kadlub N, Dainese L, Coulomb-L'Hermine A, Galmiche L, Soupre V, Lepointe HD, Vazquez MP, Picard A. Intraosseous haemangioma: semantic and medical confusion. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44:718-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Durer C, Durer S, Sharbatji M, Comba IY, Aharoni I, Majeed U. Cavernous Hemangioma of the Small Bowel: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus. 2018;10:e3113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Andrade P, Lopes S, Macedo G. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum: case report and literature review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1289-1290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Benevento A, Boni L, Dionigi G, Besana Ciani I, Danese E, Dionigi R. Multiple hemangiomas of the appendix and liver. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:860-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Levy AD, Abbott RM, Rohrmann CA, Frazier AA, Kende A. Gastrointestinal hemangiomas: imaging findings with pathologic correlation in pediatric and adult patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:1073-1081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Basbug M, Yavuz R, Dablan M, Baysal B, Gencoglu M, Yagmur Y. Isolated cavernous hemangioma: a rare benign lesion of the stomach. J Clin Med Res. 2012;4:354-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nishiyama N, Mori H, Kobara H, Fujihara S, Nomura T, Kobayashi M, Masaki T. Bleeding duodenal hemangioma: morphological changes and endoscopic mucosal resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2872-2876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Takagi C, Yamafuji K, Takahashi H, Asami A, Takeshima K, Baba H, Okamoto N, Kubochi K. A case of diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the appendix: laparoscopic surgery can facilitate diagnosis and treatment. Surg Case Rep. 2017;3:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Raju GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1697-1717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Coumbaras M, Wendum D, Monnier-Cholley L, Dahan H, Tubiana JM, Arrivé L. CT and MR imaging features of pathologically proven atypical giant hemangiomas of the liver. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1457-1463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gottlieb K, Coff P, Preiksaitis H, Juviler A, Fern P. Massive hemorrhage in pregnancy caused by a diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum--EUS as imaging modality of choice. Medscape J Med. 2008;10:206. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Wu XR, Liang WW, Zhang XW, Kang L, Lan P. Transanal total mesorectal excision as a surgical procedure for diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;39:164-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hsu RM, Horton KM, Fishman EK. Diffuse cavernous hemangiomatosis of the colon: findings on three-dimensional CT colonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1042-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dasgupta R, Fishman SJ. Management of visceral vascular anomalies. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23:216-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kandpal H, Sharma R, Srivastava DN, Sahni P, Vashisht S. Diffuse cavernous haemangioma of colon: magnetic resonance imaging features. Report of two cases. Australas Radiol. 2007;51:B147-B151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wang HT, Gao XH, Fu CG, Wang L, Meng RG, Liu LJ. Diagnosis and treatment of diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum: report of 17 cases. World J Surg. 2010;34:2477-2486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jeffery PJ, Hawley PR, Parks AG. Colo-anal sleeve anastomosis in the treatment of diffuse cavernous haemangioma involving the rectum. Br J Surg. 1976;63:678-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang AY, Ahmad NA. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the colon and rectum. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:A25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Takamatsu H, Akiyama H, Noguchi H, Tahara H, Kajiya H. Endorectal pull-through operation for diffuse cavernous hemangiomatosis of the sigmoid colon, rectum and anus. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1992;2:245-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Amarapurkar D, Jadliwala M, Punamiya S, Jhawer P, Chitale A, Amarapurkar A. Cavernous hemangiomas of the rectum: report of three cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1357-1359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wang CH. Sphincter-saving procedure for treatment of diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum and sigmoid colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:604-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hasegawa H, Teramoto T, Watanabe M, Imai Y, Muaki M, Kodaira S, Kitajima M. Diffuse cavernous hemangioma of the rectum: MR imaging with endorectal surface coil and sphincter-saving surgery. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:875-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fu ZW, Wang LX, Zhang ZY, Luo QF, Ge HY. Three-dimensional laparoscopy-assisted bowel resection for cavernous hemangioma of the rectum: Report of two cases. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2019;12:337-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zeng Z, Wu X, Chen J, Luo S, Hou Y, Kang L. Safety and Feasibility of Transanal Endoscopic Surgery for Diffuse Cavernous Hemangioma of the Rectum. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;2019:1732340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Dhumane P, Mutter D, D'Agostino J, Mavrogenis G, Leroy J, Marescaux J. Small bowel exploration and resection using single-port surgery: a safe and feasible approach. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:109-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pola S, McLemore E, Munroe C, Lin GY, Santillan C, Savides T, Fehmi SA. Rectal cancer developing in the setting of a cavernous hemangioma of the rectosigmoid colon. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Akcam M, Pirgon O, Salman H, Kockar C. Multiple gastrointestinal hemangiomatosis successfully treated with propranolol. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Junquera F, Feu F, Papo M, Videla S, Armengol JR, Bordas JM, Saperas E, Piqué JM, Malagelada JR. A multicenter, randomized, clinical trial of hormonal therapy in the prevention of rebleeding from gastrointestinal angiodysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1073-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Ge ZZ, Chen HM, Gao YJ, Liu WZ, Xu CH, Tan HH, Chen HY, Wei W, Fang JY, Xiao SD. Efficacy of thalidomide for refractory gastrointestinal bleeding from vascular malformation. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1629-37.e1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Iannone A, Principi M, Barone M, Losurdo G, Ierardi E, Di Leo A. Gastrointestinal bleeding from vascular malformations: Is octreotide effective to rescue difficult-to-treat patients? Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2016;40:373-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Fawcett WA 4th, Ferry GD, Gorin LJ, Rosenblatt HM, Brown BS, Shearer WT. Immunodeficiency secondary to structural intestinal defects. Malrotation of the small bowel and cavernous hemangioma of the jejunum. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:169-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Jin XL, Wang ZH, Xiao XB, Huang LS, Zhao XY. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17254-17259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Harada A, Umeno J, Esaki M. Gastrointestinal: Multiple venous malformations and polyps of the small intestine in Cowden syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:1819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | El-Sheikha J, Little MW, Bratby M. Rectal Venous Malformation Treated by Superior Rectal Artery Embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42:154-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Soblet J, Limaye N, Uebelhoer M, Boon LM, Vikkula M. Variable Somatic TIE2 Mutations in Half of Sporadic Venous Malformations. Mol Syndromol. 2013;4:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |