Published online Feb 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i4.538

Peer-review started: October 31, 2018

First decision: December 9, 2018

Revised: December 22, 2018

Accepted: January 3, 2019

Article in press: January 3, 2019

Published online: February 26, 2019

Processing time: 118 Days and 19 Hours

Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes), a Gram-positive facultatively intracellular bacterium, is the causative agent of human listeriosis. Listeria infection is usually found in immunocompromised patients, including elderly people, pregnant women, and newborns, whereas it is rare in healthy people. L. monocytogenes may cause meningitis, meningoencephalitis, and some very rare and severe complications, such as hydrocephalus and intracranial hemorrhage, which cause high mortality and morbidity worldwide. Up to now, reports on hydrocephalus and intracranial hemorrhage due to L. monocytogenes are few.

We herein report a case of rhombencephalitis caused by L. monocytogenes in a 29-year-old man. He was admitted to the hospital with a 2-d history of headache and fever. He consumed unpasteurized cooked beef two days before appearance. His medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, and contaminated beef intake 2 d before onset. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed Gram-positive rod infection, and blood culture was positive for L. monocytogenes. Magnetic resonance imaging findings suggested rhombencephalitis and hydrocephalus. Treatment was started empirically and then modified according to the blood culture results. Repeated CT images were suggestive of intracranial hemorrhage. Although the patient underwent aggressive external ventricular drainage, he died of a continuing deterioration of intracranial conditions.

Hydrocephalus, intracranial hemorrhage, and inappropriate antimicrobial treatment are the determinations of unfavorable outcomes.

Core tip: Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes) infection occurs predominantly in immunocompromised subjects. Various manifestations of listeriosis have been reported previously, but hydrocephalus and intracranial hemorrhage due to Listeria are rare. Hydrocephalus, intracranial hemorrhage, and inappropriate antimicrobial treatment are determinants of unfavorable outcomes. A pertinent literature review might contribute to improving our understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment of this disease.

- Citation: Liang JJ, He XY, Ye H. Rhombencephalitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes with hydrocephalus and intracranial hemorrhage: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(4): 538-547

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i4/538.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i4.538

Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes) is one of the very few bacteria that can infect neurons to produce a serious and often fatal disease, with a mortality of 20%-50%[1-4]. L. monocytogenes infection occurs predominantly in the following populations: elderly people, pregnant women, newborns, and immunodeficient patients; patients with chronic liver disease, malignant hemopathies, and diabetes; patients on chronic hemodialysis; and, less frequently, healthy individuals[5,6]. The main routes of transmission are confirmed to be through the consumption of contaminated food and via vertical transmission from mother to child[7]. Penetration of the intestinal, blood-brain, blood-choroid, and fetoplacental barriers is one of the most important virulence factors of L. monocytogenes[8]. Therefore, the manifestations of listeriosis are varied, such as gastroenteritis, septicemia, meningitis, and other conditions.

Neurolisteriosis, a central nervous system (CNS) infection caused by L. monocytogenes, represents 5%-10% of listeriosis cases and is less common in the world, especially rhombencephalitis[9-11]. Hydrocephalus and intracranial hemorrhage are rare complications of listeriosis, occurring in 10%-15% and 3% of neurolisteriosis cases, respectively[12,13]. In this paper, we present a young patient with L. monocytogenes rhombencephalitis who presented with persistent alteration of consciousness, hydrocephalus, and intracranial hemorrhage. This case is rare due to the occurrence of hydrocephalus and intracranial hemorrhage. Cases published between 1985 and 2018 that are related to Listeria hydrocephalus are reviewed in Tables 1 and 2.

| Ref. | Gestation/gender | CT/sonography on admission | Time to diagnosis of hydrocephalus | Other complications | Intervention | Outcome |

| Svare et al[22], 1991 | NB, 32 W/M | Not done | 6 wk | Epilepsy, intraventricular hemorrhage | VPD | Moderately retarded with reduced muscular tone at 3 mo |

| Madlinger et al[25], 1998 | NB, 34 W/F | Sonography, normal | 9 wk | None | VAD, VDP | Recovery |

| Chan et al[26], 2007 | NB, 31 W/M | Not done | 10 d | Subtle seizure | VPD | Significant improvement |

| Laciar et al[27], 2011 | NB, 37 W/F | Not done | 3 d | None | EVD | NA |

| Ref. | Age/gender | Immune-competent | CT on admission | Time to diagnosis of hydrocephalus | Other complications | Intervention | Outcome |

| Ulloa-Gutierrez et al[6], 2004 | 10 Y/M | Yes | Not done | 8 d | None | VPD | Recovery |

| Ulloa-Gutierrez et al[6], 2004 | 3½ Y/M | Yes | Normal | 5 d | None | VPD | Died |

| Ulloa-Gutierrez et al[6], 2004 | 6½ Y/M | Yes | Not done | 5 d | None | VPD | Died |

| Kasanmoentalib et al[12], 2010 | 57 Y/M | Yes | Not done | 5 d | Tracheoesophageal fistula | EVD | Severe cognitive slowness |

| Ito et al[13], 2007 | 62 Y/M | No | Normal | 14 d | Ventriculitis | EVD | Improvement, remained confused and disoriented |

| McCaffrey et al[20], 2012 | 57 Y/M | No | Yes, hydrocephalus | 1 d | Ventriculitis | EVD | NA |

| Dhiwakar et al[21], 2007 | 40 Y/F | No | Not done | 2 mo | Seizures, ventriculitis, basal arachnoiditis, cerebellar tonsillar herniation | VPD, VAD | Near-complete recovery |

| Chan et al[26], 2001 | 42 Y/M | Yes | Yes, hydrocephalus | 4 d | Subdural collection, extensive; cerebritis and ventriculitis | EVD | Died |

| Lee et al[28], 2010 | 7 Y/F | Yes | Not done | 10 d | None | EVD, VPD | Recovery |

| Platnaris et al[29], 2009 | 7 M/M | Yes | Normal | 10 d | Seizures | EVD | Normal development having achieved skills according to his age at 22 mo of age |

| Papandreou et al[30], 2015 | 3 Y/F | Yes | Normal | 8 d | Cerebellar tonsillar herniation, ventriculitis, and AIDP | EVD, VPD | Incomplete recovery |

| Gaini et al[31], 2015 | 74 Y/M | Yes | Normal | 6 d | Brain abscess | EVD | Severe sequelae, died 1 yr later |

| Ruggieri et al[32], 2014 | 27 Y/F | Yes | Yes, hindbrain multifocal lesions | 9 d | None | EVD | Only a motor deficit of the right arm remained |

| Cunha et al[33], 2004 | 50 Y/M | Yes | Yes, hydrocephalus | 1 d | None | No | Died 10 d after admission |

| Frat et al[34], 2001 | 72 Y/F | Yes | Normal | 12 d | Seizures | VPD | Recovery after 5 mo of rehabilitative care |

| Raps et al[35], 1989 | 47 Y/F | No | Not done | Several weeks | Cervical cord compression | EVD, VPD | No significant deficit 6 mo later |

| Yang et al[36], 2006 | 42 Y/M | No | Normal | 9 d | Seizures | ORI | Recovery |

| Rana et al[37], 2014 | 75 Y/M | No | Not done | 5 d | None | VPD | Gradual recovery |

A 29-year-old Chinese man was admitted to the hospital with a 2-d history of intermittent fevers of up to 39 °C, and forehead headache without nausea.

Two days prior to onset, he had consumed unpasteurized cooked beef that was stored in the refrigerator for a few days.

His medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus, which was poorly controlled, fatty liver, smoking, and drinking.

He denied a family history of hypertension and stroke.

The physical examination was unremarkable, except for nuchal rigidity.

The blood laboratory findings showed that glucose, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were high, while white blood cells (WBCs), red blood cells, hemoglobin, urea, creatinine, serum minerals, and autoimmune antibodies were normal. The first lumbar puncture on admission revealed a turbid cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with 2090 leukocytes/mm3 (30% neutrophils, 70% monocytes), 233.85 mg/dL protein, 1.4 mmol/L glucose (serum glucose 9 mmol/L), and pressure > 33 cmH2O. CSF Gram stain showed Gram-positive rods and was negative for fungi and acid-fast bacilli (Table 3). On the 8th day, the blood cultures yielded L. monocytogenes, which was susceptible to ampicillin, erythrocin, meropenem, and penicillin but resistant to sulfamethoxazole. CSF and urine cultures were negative. Repeated CSF examination on the 14th and 28th day showed a greater decrease in WBCs and protein (Table 3).

| CSF test | On the 2nd d | On the 14th d | On the 28th d1 |

| Color | Turbid | Turbid | Mildly turbid |

| Pressure(cm H2O) | > 33 | 12.5 | NA |

| Erythrocyte count (/mm3) | 0 | 13198 | 3313 |

| WBC count (/mm3) | 2090 | 782 | 85 |

| WBC distribution (L/N) | 70/30 | 3/97 | 17/68 |

| Protein (mg/dL) | 233.85 | 441 | 119 |

| CSF glucose (mmol/L) | 1.40 | 5.42 | 5.60 |

| Plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 9.00 | 11.05 | 10.0 |

| Gram stain | Gram-positive rods | Normal | Normal |

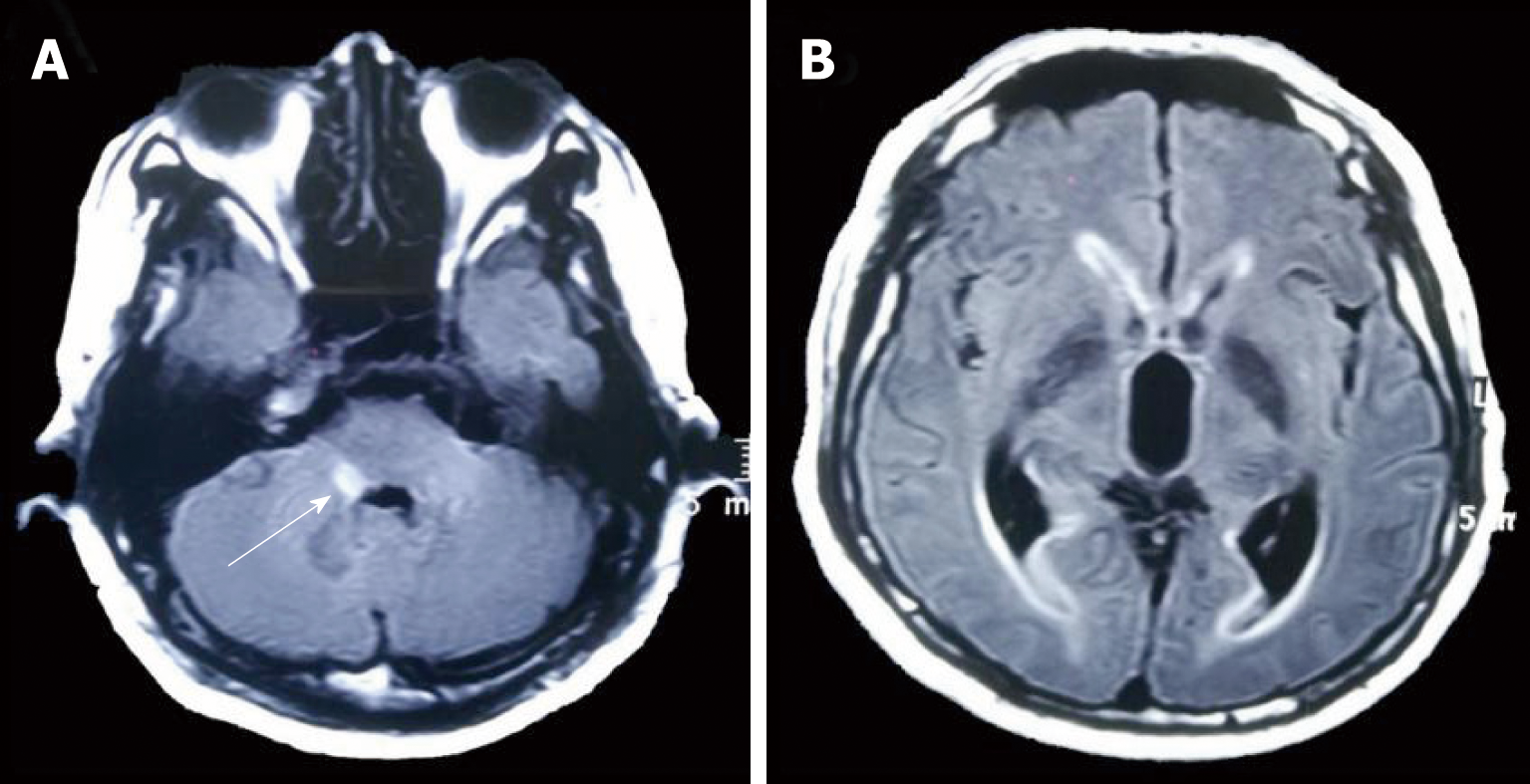

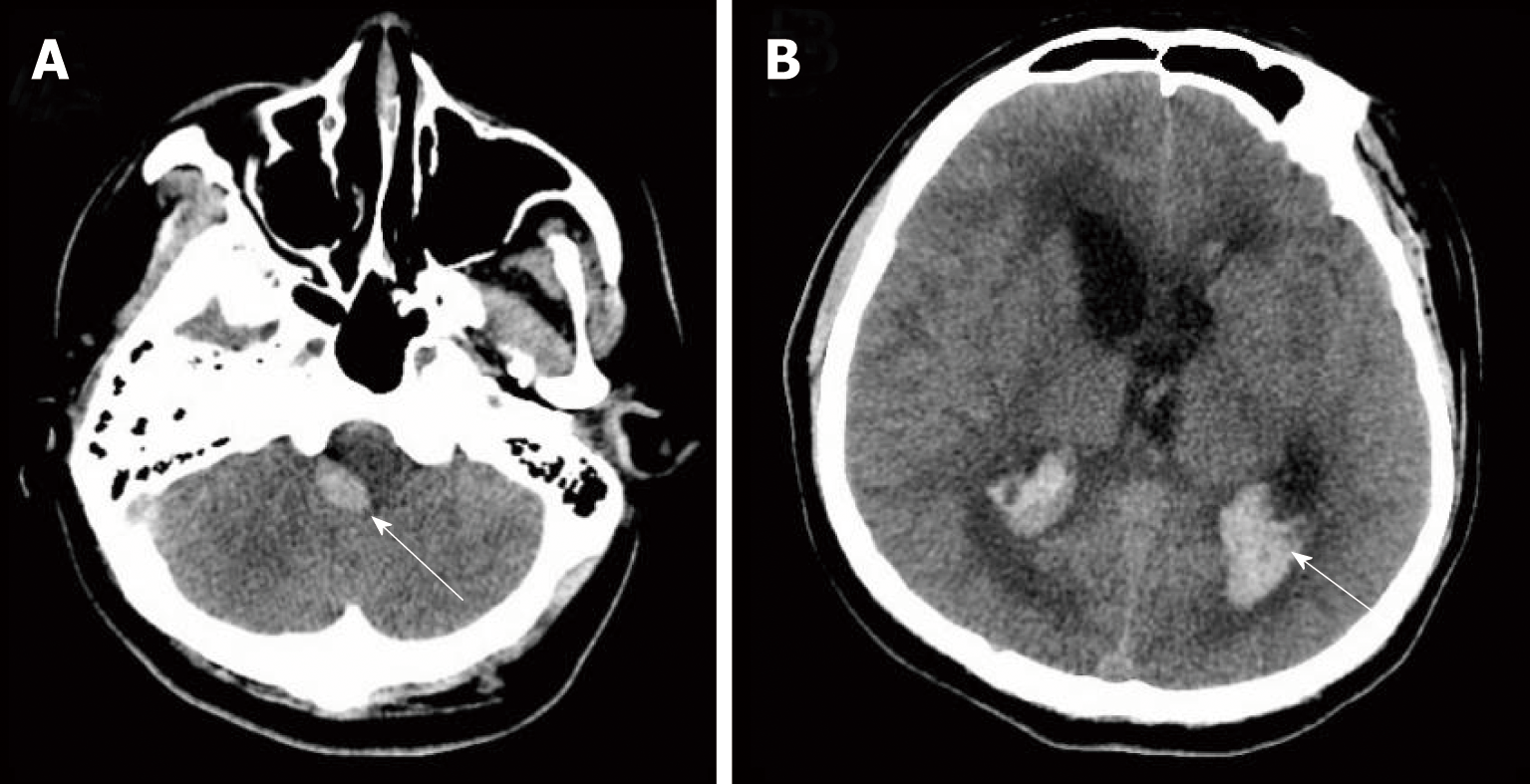

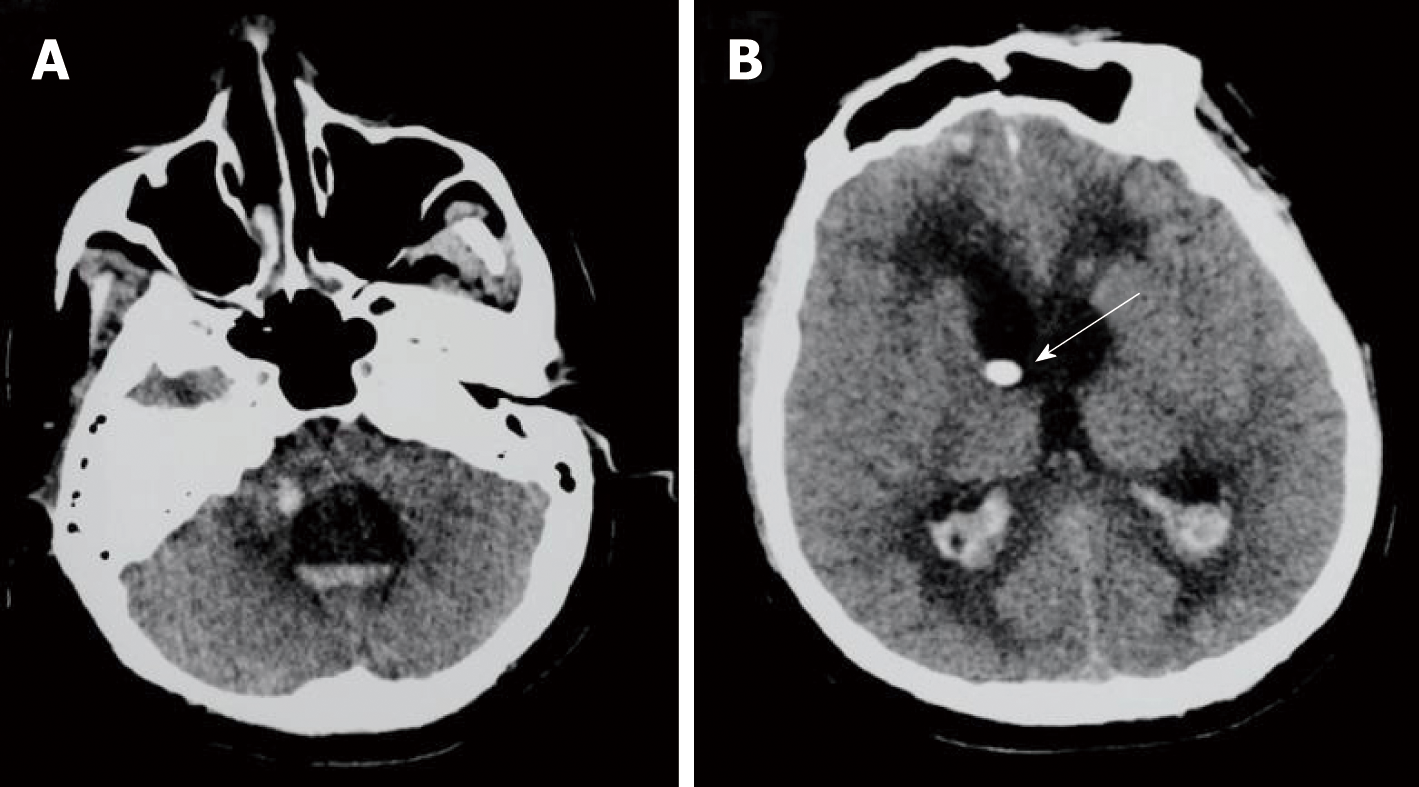

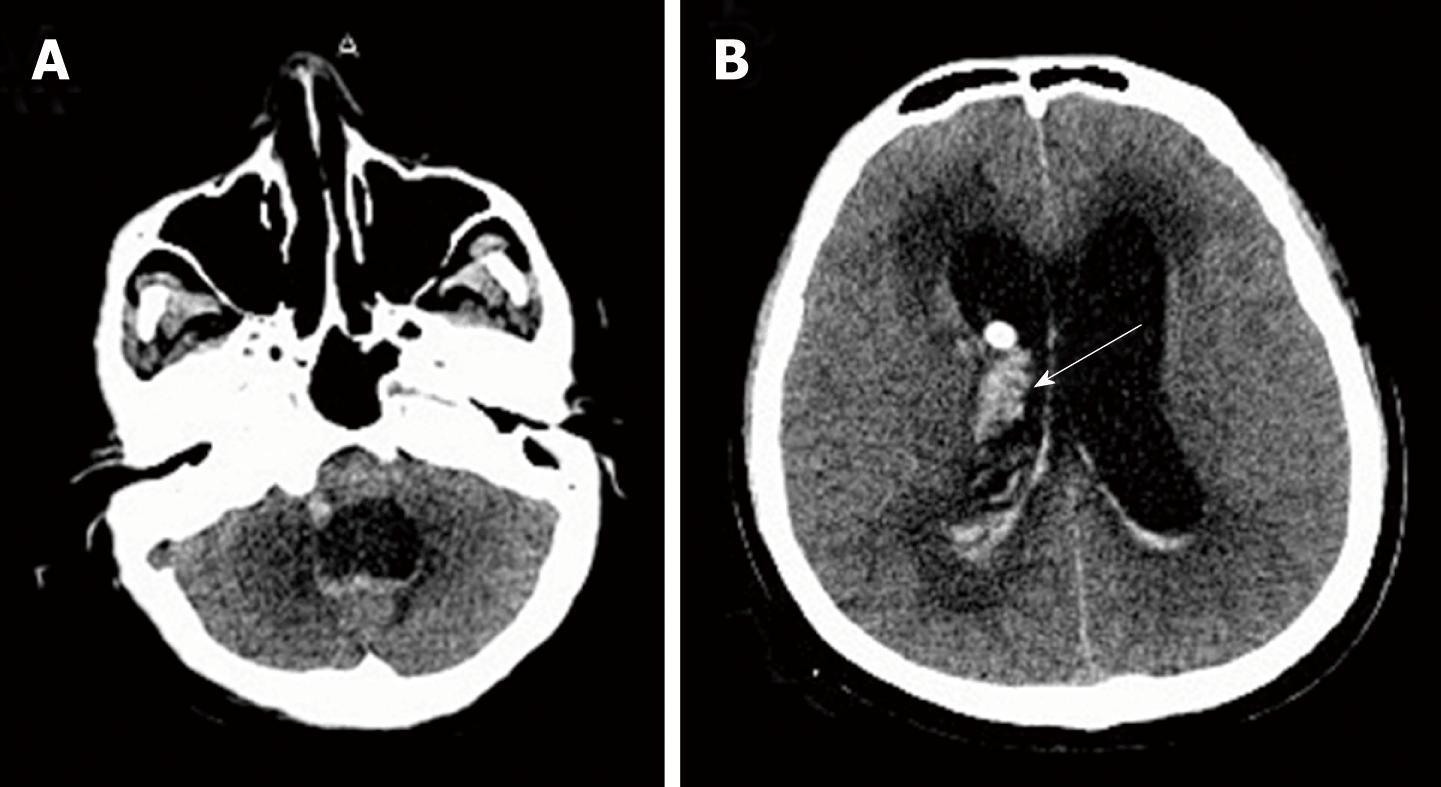

The initial brain CT was unremarkable, and chest CT showed bilateral bronchopneumonia. On the 4th day of admission, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed an abnormally high T2 flow attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal in the right pons and prominent temporal horns with enlargement of the ventricles (Figure 1). On the 14th day, brain CT showed hemorrhage of the right pons and hydrocephalus (bilateral lateral ventricular and the third ventricle hydrocephalus) (Figure 2). The 3rd cerebral CT was performed on the day after extraventricular drainage, revealed significant dilatation of fourth ventricle, and no remission in lateral ventricles (Figure 3). The 4th brain CT on the 29th day showed rehaemorrhagia of the lateral ventricle and a larger ventricular system (Figure 4).

The patient was finally diagnosed with Listeria rhombencephalitis, hydrocephalus, and intracranial hemorrhage.

Although empiric antibiotic therapy for bacterial meningitis (Ceftriaxone 2 g, every 12 h for 2 d, followed by meropenem 1 g, every 8 h for 2 d) and all other supportive symptomatic treatments were administered after performing blood cultures, the patient developed new symptoms with fever, sinus tachycardia, tachypnea, confusion [Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score 12/15], bilateral horizontal nystagmus, bilateral abducens nerve palsy, dysarthria, and weakness of all four limbs. He was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) on the 5th day. On the 8th day, he went into coma (GCS score 5/15), and was intubated and ventilated without autonomous respiration. According to blood cultures, new antibiotic therapy with ampicillin, etimicin and meropenem was administered. On the 12th day, etimicin was discontinued as he became afebrile. We performed an extraventricular drainage to relieve hydrocephalus on the 22nd day (Figure 3). On the 29th day, because of rehaemorrhagia of the lateral ventricle, his condition rapidly deteriorated (GCS score 3/15), with anisocoria (left pupil 4 mm and right pupil 2 mm).

The patient died on the 31st day. Autopsy could not be performed.

Although L. monocytogenes has been reported to be the third most common cause of community-acquired bacterial meningitis, following pneumococcal and meningococcal meningitis in adults, its occurrence is relatively rare, accounting for only 5% of encephalitis cases in metropolitan France[14]. Listeria has an important impact on public health, with high hospitalization and mortality rates despite antibiotic treatment[15]. As listeriosis is not incorporated into the national monitoring system for cases, epidemiological data on Listeria are scarce in China[7,16]. In a study published in 2013, Feng et al[16] reviewed 147 cases of listeriosis in China from 1964 to 2010, with neurolisteriosis accounting for 31% of cases. The overall case-fatality rate was 26%, highest among neonatal cases (46%) and lowest among pregnant cases (4%)[16]. In a study conducted by Wang et al[7], 38 cases of listeriosis, including 5 neonatal, 8 maternal, and 25 nonmaternal cases, were reviewed in China between 1999 and 2011, and the case-fatality rates for neonatal, maternal, and nonmaternal cases were 20%, 0%, and 26%, respectively[7].

CSF and blood cultures are the most specific for diagnosis. Early diagnosis of neurolisteriosis is difficult not only because the presentation of CSF is similar to the manifestations of other bacterial encephalitis and meningitis (pleocytosis, hyperproteinorrachia, and hypoglycorrhachia) but also because approximately 50% of CSF Gram stains are negative[17]. Jubelt et al[18] reported that approximately three-quarters of patients have CSF pleocytosis, with approximately equal percentages of mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells. In our case, there was an initial predominance of lymphocytic cells, which then turned to mononuclear cell predominance; this change might be related to pathological processes and the application of antibiotics. Listeria is usually revealed first on blood cultures, which are positive in 62% of encephalitis cases[19]. Therefore, early before antibiotic administration, repeated blood and CSF cultures are necessary and helpful for early and differential diagnoses.

L. monocytogenes infection most frequently presents as acute bacterial meningitis, less commonly as meningoencephalitis, and least commonly as rhombencephalitis, accounting for approximately 10% of neurolisteriosis cases[12,13]. Although the exact mechanism of rhombencephalitis remains poorly understood, L. monocytogenes has a well-known predilection for the brainstem. Karlsson et al[9] reviewed 120 patients with Listeria rhombencephalitis and suggested that L. monocytogenes enters the cerebellopontine angle through the trigeminal nerve in a subset of patients, invading the brainstem via the sensory trigeminal nuclei. As MRI is superior to CT in detecting subtentorial abnormal lesions, it has become more helpful for diagnosing rhombencephalitis, which has a high signal on T2-FLAIR sequences.

L. monocytogenes complications, such as acute hydrocephalus, hemorrhage, brain abscess, spine abscess, cerebritis, and ventriculitis, can develop, and the mortality associated with these complications is significantly high. Hydrocephalus is most common in tuberculous encephalitis but rare in listeriosis, with an approximate 3% incidence of L. monocytogenes meningoencephalitis in adults[13]. The exact mechanism of hydrocephalus remains unclear. The development of meningitis-associated hydrocephalus may be due to several mechanisms, such as a high level of CSF protein, impaired CSF absorption due to the obliteration of the subarachnoid space by meningeal exudates, and/or blockade of the CSF pathway by leptomeningeal inflammation[20].

Retrospective analysis of hydrocephalus due to listeriosis is scarce at present, and most of the literature consists of case reports. The time to onset of hydrocephalus varies greatly, ranging from 1 d to 9 wk[20,21]. Ventricular drainage may not be an effective way to relieve hydrocephalus and improve survival[12,14]. A study from the Netherlands reviewed 26 hydrocephalus cases in 577 bacterial meningitis patients (4.5%), including four cases of L. monocytogenes (15%), all of whom underwent placement of an external ventricular drain catheter[14]. None of these patients improved clinically after catheter placement, and all had poor outcomes for hydrocephalus, with three deaths (75%) and one case of serious sequela (25%), thus indicating that patients with hydrocephalus were at a high risk for unfavorable outcomes and that hydrocephalus was an independent risk factor for death[14]. In our case, the patient underwent ventricular drainage, but a continuous improvement in cognitive function was not obvious.

Another rare complication of Listeria meningitis is intracranial hemorrhage, which is also one of the determinants of unfavorable outcomes[2]. Most reported cases of intracranial hemorrhage occur in infants and young children, while the condition is quite rare in adults. Svarea et al[22] reported a case of maternal listeriosis resulting in preterm delivery and intraventricular hemorrhage, which was diagnosed by an ultrasound scan. In a prospective study of 860 episodes with bacterial meningitis in the Netherlands, 24 (2.79%) were diagnosed with intracranial hemorrhage, with S. pneumoniae accounting for 67% and L. monocytogenes accounting for 4%[2]. The underlying pathophysiology of intraventricular hemorrhage in L. monocytogenes infection is still unknown and may be related to dysregulation of both the coagulation and fibrinolytic pathways and to vascular endothelial cell swelling and activation[2].

An empirical therapy for bacterial meningitis, generally third-generation cephalosporins, is always applied at an early stage when bacterial meningitis is suspected. However, this treatment option does not cover L. monocytogenes. Former publications have demonstrated that inappropriate empirical antibiotic therapy leads to unfavorable outcomes[23]. Therefore, it is very important to adjust the appropriate antibiotic therapy as soon as possible once Listeria is highly suspected or confirmed.

Listeria is known to be difficult to treat, not only because L. monocytogenes has an intracellular life cycle but also because only a few antibiotics demonstrate activity against Listeria[24]. Due to the lack of multicenter clinical controlled studies, the optimal antibiotic regimen and duration for neurolisteriosis have not been definitively defined. However, amoxicillin, ampicillin, and penicillin G are generally considered effective regimens in the treatment of listeriosis[24]. The addition of aminoglycosides (such as gentamicin) could be considered a treatment regimen for L. monocytogenes meningitis, but its use remains controversial due to the occurrence of kidney damage[24]. The drugs should be applied at high doses, and the duration of this treatment should be extended to 21 d or longer, until complete eradication, to prevent relapse[24]. Furthermore, cotrimoxazole, rifampin, meropenem, linezolid, tetracyclines, and moxifloxacin should also be considered active against Listeria[23]. In our patient, the combination of ampicillin, etimicin, and meropenem was used for Listeria, and it was proven effective by repeated CSF examinations (Table 3).

We report a case of acute hydrocephalus and intracranial hemorrhage due to complications from L. monocytogenes rhombencephalitis. The pathogenesis of complications has been reviewed. L. monocytogenes may be prone to entering the brainstem through the trigeminal nerve; hydrocephalus may be close with a high level of CSF protein and impaired CSF absorption and circulation; the occurrence of intracranial hemorrhage may be related to dysregulation of both the coagulation and fibrinolytic pathways and to vascular endothelial cell swelling and activation. Hydrocephalus, intracranial hemorrhage, and inappropriate antimicrobial treatment are the determinations of unfavorable outcomes.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Bhalla AS, Chowdhury FH, Vaudo G S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Cossart P. Interactions of the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes with mammalian cells: bacterial factors, cellular ligands, and signaling. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 1998;43:291-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mook-Kanamori BB, Fritz D, Brouwer MC, van der Ende A, van de Beek D. Intracerebral hemorrhages in adults with community associated bacterial meningitis in adults: should we reconsider anticoagulant therapy? PLoS One. 2012;7:e45271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Goulenok T, Buzelé R, Duval X, Bruneel F, Stahl JP, Fantin B. Management of adult infectious encephalitis in metropolitan France. Med Mal Infect. 2017;47:206-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dons L, Jin Y, Kristensson K, Rottenberg ME. Axonal transport of Listeria monocytogenes and nerve-cell-induced bacterial killing. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2529-2537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ben Shimol S, Einhorn M, Greenberg D. Listeria meningitis and ventriculitis in an immunocompetent child: case report and literature review. Infection. 2012;40:207-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ulloa-Gutierrez R, Avila-Agüero ML, Huertas E. Fulminant Listeria monocytogenes meningitis complicated with acute hydrocephalus in healthy children beyond the newborn period. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:233-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang HL, Ghanem KG, Wang P, Yang S, Li TS. Listeriosis at a tertiary care hospital in beijing, china: high prevalence of nonclustered healthcare-associated cases among adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:666-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Disson O, Lecuit M. Targeting of the central nervous system by Listeria monocytogenes. Virulence. 2012;3:213-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Karlsson WK, Harboe ZB, Roed C, Monrad JB, Lindelof M, Larsen VA, Kondziella D. Early trigeminal nerve involvement in Listeria monocytogenes rhombencephalitis: case series and systematic review. J Neurol. 2017;264:1875-1884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Antal EA, Dietrichs E, Løberg EM, Melby KK, Maehlen J. Brain stem encephalitis in listeriosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37:190-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Charlier C, Perrodeau É, Leclercq A, Cazenave B, Pilmis B, Henry B, Lopes A, Maury MM, Moura A, Goffinet F, Dieye HB, Thouvenot P, Ungeheuer MN, Tourdjman M, Goulet V, de Valk H, Lortholary O, Ravaud P, Lecuit M; MONALISA study group. Clinical features and prognostic factors of listeriosis: the MONALISA national prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:510-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 341] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kasanmoentalib ES, Brouwer MC, van der Ende A, van de Beek D. Hydrocephalus in adults with community-acquired bacterial meningitis. Neurology. 2010;75:918-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ito H, Kobayashi S, Iino M, Kamei T, Takanashi Y. Listeria monocytogenes meningoencephalitis presenting with hydrocephalus and ventriculitis. Intern Med. 2008;47:323-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pelegrín I, Moragas M, Suárez C, Ribera A, Verdaguer R, Martínez-Yelamos S, Rubio-Borrego F, Ariza J, Viladrich PF, Cabellos C. Listeria monocytogenes meningoencephalitis in adults: analysis of factors related to unfavourable outcome. Infection. 2014;42:817-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Mailles A, Lecuit M, Goulet V, Leclercq A, Stahl JP; National Study on Listeriosis Encephalitis Steering Committee. Listeria monocytogenes encephalitis in France. Med Mal Infect. 2011;41:594-601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Feng Y, Wu S, Varma JK, Klena JD, Angulo FJ, Ran L. Systematic review of human listeriosis in China, 1964-2010. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:1248-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cunha BA, Fatehpuria R, Eisenstein LE. Listeria monocytogenes encephalitis mimicking Herpes Simplex virus encephalitis: the differential diagnostic importance of cerebrospinal fluid lactic acid levels. Heart Lung. 2007;36:226-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jubelt B, Mihai C, Li TM, Veerapaneni P. Rhombencephalitis / brainstem encephalitis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2011;11:543-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Reynaud L, Graf M, Gentile I, Cerini R, Ciampi R, Noce S, Borrelli F, Viola C, Gentile F, Briganti F, Borgia G. A rare case of brainstem encephalitis by Listeria monocytogenes with isolated mesencephalic localization. Case report and review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;58:121-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McCaffrey LM, Petelin A, Cunha BA. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) cerebritis versus Listeria monocytogenes meningoencephalitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus on chronic corticosteroid therapy: the diagnostic importance of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of lactic acid levels. Heart Lung. 2012;41:394-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dhiwakar M, Basu S, Ramaswamy R, Mallucci C. Neurolisteriosis causing hydrocephalus, trapped fourth ventricle, hindbrain herniation and syringomyelia. Br J Neurosurg. 2004;18:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Svare J, Andersen LF, Langhoff-Roos J, Madsen H, Bruun B. Maternal-fetal listeriosis: 2 case reports. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1991;31:179-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hof H. An update on the medical management of listeriosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:1727-1735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | van de Beek D, Cabellos C, Dzupova O, Esposito S, Klein M, Kloek AT, Leib SL, Mourvillier B, Ostergaard C, Pagliano P, Pfister HW, Read RC, Sipahi OR, Brouwer MC; ESCMID Study Group for Infections of the Brain (ESGIB). ESCMID guideline: diagnosis and treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22 Suppl 3:S37-S62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 499] [Article Influence: 55.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Madlinger AG, Krauss JK. Intramedullary brain stem cyst and trapped IV ventricle after infection with Listeria monocytogenes. Childs Nerv Syst. 1998;14:747-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chan YC, Ho KH, Tambyah PA, Lee KH, Ong BK. Listeria meningoencephalitis: two cases and a review of the literature. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2001;30:659-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Laciar AL, Vaca Ruiz ML, Le Monnier A. Neonatal Listeria-meningitis in San Luis, Argentina: a three-case report. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2011;43:45-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lee JE, Cho WK, Nam CH, Jung MH, Kang JH, Suh BK. A case of meningoencephalitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes in a healthy child. Korean J Pediatr. 2010;53:653-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Platnaris A, Hatzimichael A, Ktenidou-Kartali S, Kontoyiannides K, Kollios K, Anagnostopoulos J, Roilides E. A case of Listeria meningoencephalitis complicated by hydrocephalus in an immunocompetent infant. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:343-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Papandreou A, Hedrera-Fernandez A, Kaliakatsos M, Chong WK, Bhate S. An unusual presentation of paediatric Listeria meningitis with selective spinal grey matter involvement and acute demyelinating polyneuropathy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016;20:196-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gaini S, Karlsen GH, Nandy A, Madsen H, Christiansen DH, Á Borg S. Culture Negative Listeria monocytogenes Meningitis Resulting in Hydrocephalus and Severe Neurological Sequelae in a Previously Healthy Immunocompetent Man with Penicillin Allergy. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:248302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ruggieri F, Cerri M, Beretta L. Infective rhomboencephalitis and inverted Takotsubo: neurogenic-stunned myocardium or myocarditis? Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:191.e1-191.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cunha BA, Filozov A, Remé P. Listeria monocytogenes encephalitis mimicking West Nile encephalitis. Heart Lung. 2004;33:61-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Frat JP, Veinstein A, Wager M, Burucoa C, Robert R. Reversible acute hydrocephalus complicating Listeria monocytogenes meningitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:512-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Raps EC, Gutmann DH, Brorson JR, O'Connor M, Hurtig HI. Symptomatic hydrocephalus and reversible spinal cord compression in Listeria monocytogenes meningitis. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:620-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Yang CC, Yeh CH, Tsai TC, Yu WL. Acute symptomatic hydrocephalus in Listeria monocytogenes meningitis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2006;39:255-258. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Rana F, Shaikh MM, Bowles J. Listeria meningitis and resultant symptomatic hydrocephalus complicating infliximab treatment for ulcerative colitis. JRSM Open. 2014;5:2054270414522223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |