Published online Feb 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i4.441

Peer-review started: November 5, 2018

First decision: December 20, 2018

Revised: January 9, 2019

Accepted: January 26, 2019

Article in press: January 26, 2019

Published online: February 26, 2019

Processing time: 114 Days and 2.7 Hours

Endometriosis is a common disease for women of reproductive age. However, when it involves intestines, it is difficult to diagnose preoperatively because its symptoms overlap with other diseases and the results of evaluations can be unspecific. Thus it is important to know the clinical characteristics of intestinal endometriosis and how to exactly diagnose.

To analyze patients in whom intestinal endometriosis was diagnosed after surgical treatments, and to evaluate the clinical characteristics of preoperatively misdiagnosed cases.

We retrospectively reviewed the pathologic reports of 30 patients diagnosed as having intestinal endometriosis based on surgical specimens between January 2000 and December 2017. We reviewed their clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes.

Twenty-three (76.6%) patients showed symptoms associated with endometriosis, with dysmenorrhea being the most common (n = 9, 30.0%). Thirteen patients (43.3%) had a history of pelvic surgeries. Ten patients (33.3%) had a history of treatment for endometriosis. Only 4 patients (13.3%) had a diagnosis of endometriosis based on endoscopic biopsy findings. According to preoperative evaluations, 13 patients (43.3%) had an initial diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis and 17 patients (56.6%) were misdiagnosed as having other diseases. The most common misdiagnosis was submucosal tumor in the large intestine (n = 8, 26.7%), followed by malignancies of the colon/rectum (n = 3, 10.0%) and ovary (n = 3, 10.0%). According to the Clavien-Dindo classification, 5 complications were grade I or II and 2 complications were grade IIIa. The median follow-up period was 26.9 (0.6-132.1) mo, and only 1 patient had a recurrence of endometriosis.

Intestinal endometriosis is difficult to diagnose preoperatively because it mimics various intestinal diseases. Thus, if women of reproductive age have ambiguous symptoms and signs with nonspecific radiologic and/or endoscopic findings, intestinal endometriosis should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Core tip: Intestinal endometriosis is difficult to diagnose preoperatively because it mimics various intestinal diseases. The aim of this study is to analyze patients in whom intestinal endometriosis was diagnosed after surgical treatments, and to evaluate the clinical characteristics of preoperatively misdiagnosed cases. According to preoperative evaluations, 13 patients (43.3%) had an initial diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis and 17 patients (56.6%) were misdiagnosed as having other diseases. Only 4 patients (13.3%) had a diagnosis of endometriosis based on endoscopic biopsy findings. Thirteen patients (43.3%) had a history of pelvic surgeries. Ten patients (33.3%) had a history of treatment for endometriosis. Thus, if women of reproductive age have ambiguous symptoms and signs with nonspecific radiologic and/or endoscopic findings, intestinal endometriosis should be included in the differential diagnosis.

- Citation: Bong JW, Yu CS, Lee JL, Kim CW, Yoon YS, Park IJ, Lim SB, Kim JC. Intestinal endometriosis: Diagnostic ambiguities and surgical outcomes. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(4): 441-451

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i4/441.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i4.441

Endometriosis is defined as a disease of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus inducing a chronic inflammatory reaction[1]. Endometriosis is a relatively common disease with a reported incidence of up to 15% in women of reproductive age[1]. The mechanism of endometriosis has not been known well; however, ectopic implantation of endometrial cells following retrograde menstruation via the Fallopian tube into the pelvis is accepted as the main cause of endometriosis. The clinical manifestations of endometriosis include pelvic pain, infertility, and a pelvic mass. Because endometrial cells are influenced by hormonal changes, symptoms of endometriosis often worsen during the menstrual period.

When endometrial-like glands and stroma infiltrate the bowel wall, reaching at least the subserous fat tissue or the adjacent subserous plexus, the condition is diagnosed as intestinal endometriosis[2]. The incidence of intestinal endometriosis is estimated to be from 3% to 37% of all endometriosis cases[3]. In most cases (> 90%), intestinal endometriosis involves the sigmoid colon or rectum and the posterior pelvic compartment peritoneum[4]. It presents with symptoms including diarrhea, constipation, tenesmus, and rectal bleeding. Pelvic pain and infertility can also occur with or without these symptoms. The aims of treatment are to relieve symptoms and recover fertility with minimal injury to other gynecologic organs. Medical treatments including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral contraceptives, progesterone, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues were reported to be effective in relieving symptoms and in eradicating microscopic disease and diseases of vital structures[2]. En bloc resection is preferred to completely remove the endometrial tissue because multifocality (another lesion within 2 cm from the main lesion) and multicentricity (another lesion beyond 2 cm from the main lesion) are common in intestinal endometriosis (incidence: 62% and 38%, respectively)[5].

Many diseases can be included in the differential diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis, such as irritable bowel syndrome, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, ischemic colitis, and metastatic tumor[6]. However, reaching a diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis is complicated because its symptoms overlap with those of other diseases. Additionally, because endoscopically obtained biopsy material has a superficial origin and endometriosis usually involves the deeper layers of the bowel wall, tissue obtained in an endoscopic manner may reflect chronic injury but lack endometriotic foci[7]. Lesions, especially if firm and obstructive, can also be mistaken intraoperatively for gastrointestinal carcinoma. Misdiagnosis inevitably contributes to diagnostic delay and increased economic burden because of inappropriate management[6]. In this study, we reviewed the clinical courses of patients in whom intestinal endometriosis was diagnosed after surgical treatments at our institute, to evaluate the clinical characteristics of preoperatively misdiagnosed cases and the surgical outcomes of intestinal endometriosis.

From the database about pathologic reports of our institution, a tertiary referral center, we searched and collected medical records of patients who had been diagnosed with intestinal endometriosis from their surgical specimens from January 2000 to December 2017. We reviewed the clinical characteristics of the patients, including age at surgical treatment and history of abdominal surgery and endometriosis. Clinical presentation and computed tomography (CT) imaging findings related to the diagnosis were obtained from the medical records. Endoscopic findings were collected and categorized according mucosal change and eccentric wall thickening. Biopsy specimens were obtained from lesions with abnormal changes by using standard endoscopic forceps. Preoperative diagnosis, locations of lesions, types of bowel surgeries, and combined operations were analyzed. Additionally, we collected data associated with postoperative complications within 30 d after the surgery and categorized them according to the Clavien-Dindo classification (CDC) to evaluate surgical outcomes. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB approval number: S2017-2143-0001).

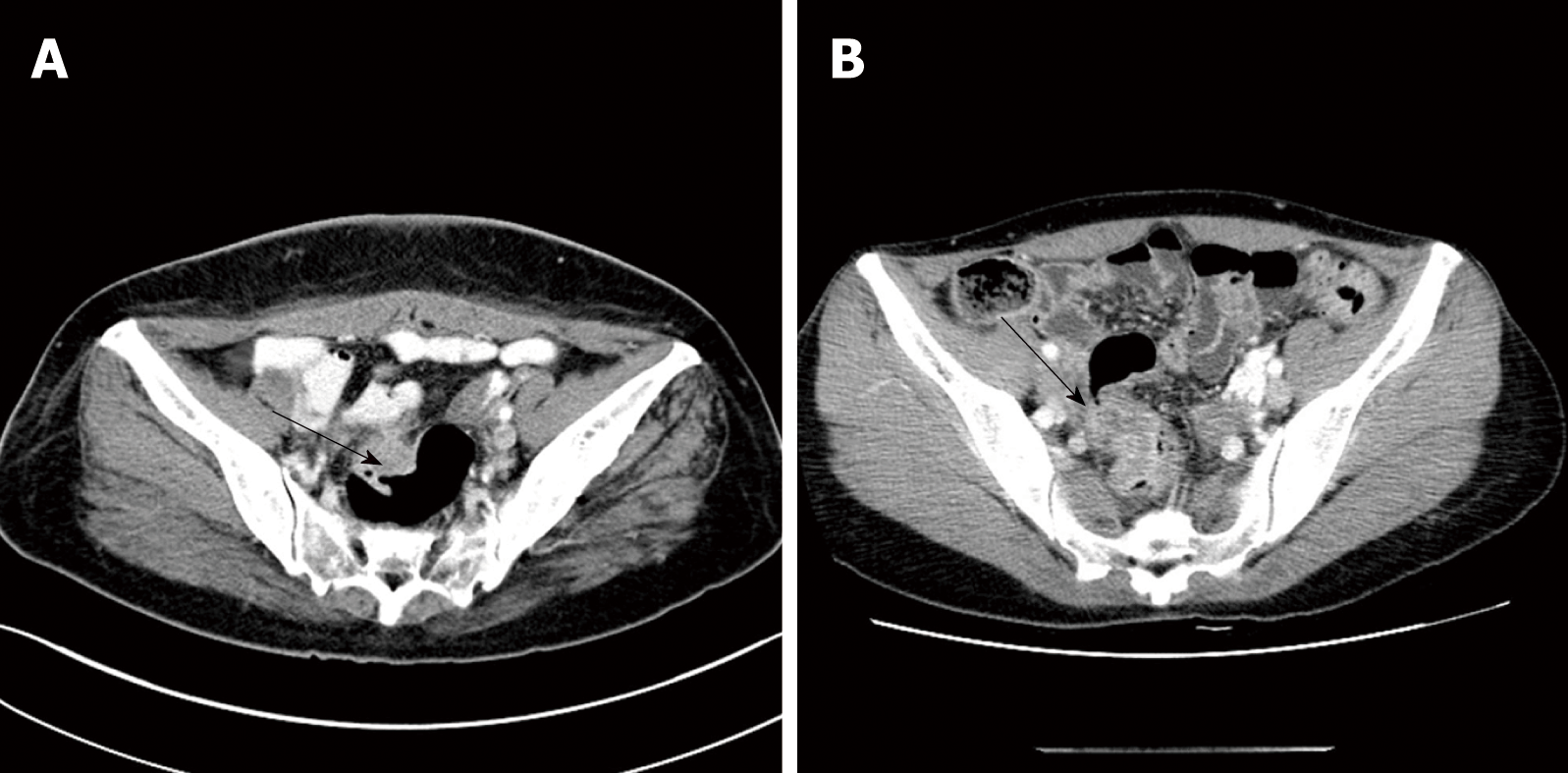

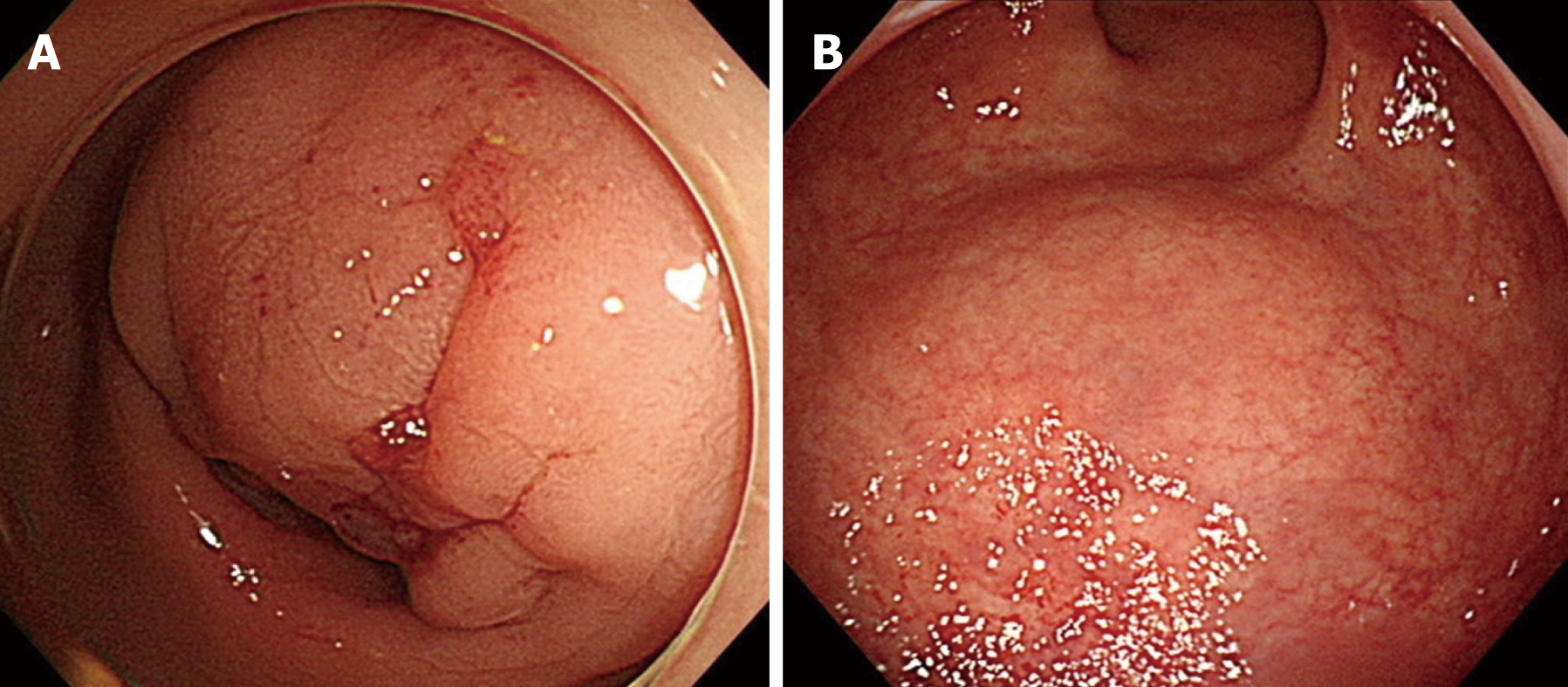

Fifty patients with histologically confirmed intestinal endometriosis were identified and we retrospectively reviewed their medical records. Among them, cases were excluded if the diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis was made incidentally during surgical resection for other pathologies, including colorectal cancer (n = 10), ovarian cancer (n = 7), uterine myoma (n = 2), and Crohn’s disease (n = 1). Finally, a total of 30 patients were included in this study. The median age at surgery for intestinal endometriosis was 43 (29-53) years (Table 1). Twenty-three (76.7%) patients showed symptoms associated with endometriosis, with dysmenorrhea being the most common (n = 9, 30.0%), followed by hematochezia (n = 5, 16.7%) and abdominal pain (n = 4, 13.3%). In the remaining 7 patients (23.3%), intestinal endometriosis was incidentally diagnosed using endoscopic screening. Thirteen patients (43.3%) had a history of pelvic surgeries including cesarean section, transabdominal hysterectomy, and/or unilateral/bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for uterine myoma, ovarian cyst, and pelvic endometriosis. Additionally, 10 patients (33.3%) had a history of treatment for endometriosis and 6 patients (20.0%) had been previously treated with both surgical and medical therapies. Figure 1 shows the finding of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a patient who were diagnosed preoperatively with intestinal endometriosis at rectosigmoid colon. A nodule infiltrating the rectal wall from the outside is detectable. Preoperative CT images showed a mass in the intestine or other gynecologic organs in most patients (n = 23, 76.7%; Table 2). Figure 2A shows a CT image of a patient who had a diagnosis of rectal submucosal tumor preoperatively. An about 3-cm mass with mild wall thickening was identified at the upper rectum without any infiltration and luminal obstruction. Figure 2B is a CT image from another patient, showing wall thickness and infiltration at the rectosigmoid colon without a definite mass. This patient had a diagnosis of rectosigmoid colon cancer preoperatively. The most common endoscopic finding was eccentric wall thickening of the bowel mucosa (n = 16, 53.4%). Of these 16 patients, 8 patients (26.7%) showed no mucosal change in the colonic lumen. Moreover, in 4 patients (13.3%), no abnormal change was identified in colonoscopic findings. Only 4 patients (13.3%) had a diagnosis of endometriosis based on endoscopic biopsies. Figure 3A demonstrates the endoscopic biopsy of a patient who was diagnosed as having rectal endometriosis. Severe luminal obstruction with extrinsic compression and hyperemic change was identified in the mucosa. Figure 3B shows the endoscopic findings of another patient who was diagnosed as having submucosal tumor at the sigmoid colon. A mass was appeared to be in the submucosal layer without abnormal change in the colonic mucosa, and the diagnosis based on endoscopic biopsy was nonspecific colitis.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Age, yr, median (range) | 43 (29-53) |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 15 (50.0) |

| Pelvic surgery | 13 (43.3) |

| Cesarean section | 9 (30.0) |

| TAH ± BSO | 4 (13.3) |

| Splenectomy | 1 (3.3) |

| History of endometriosis | 10 (33.3) |

| Surgical treatment | 9 (30.0) |

| Ovarian cystectomy | 3 (10.0) |

| TAH ± SO | 2 (6.6) |

| Oophorectomy | 2 (6.6) |

| Adhesiolysis | 2 (6.6) |

| Medical treatment | 7 (23.3) |

| Both | 6 (20.0) |

| Initial symptom | |

| Dysmenorrhea | 9 (30.0) |

| Hematochezia | 5 (16.7) |

| Abdominal pain | 4 (13.3) |

| Constipation | 2 (6.7) |

| Abdominal mass | 1 (3.3) |

| Urinary discomfort | 1 (3.3) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (3.3) |

| No symptom | 7 (23.3) |

| Findings | n (%) |

| Computed tomography | |

| Eccentric intestinal wall thickening with a mass | 15 (50.0) |

| Mass in the ovary or uterus | 8 (26.7) |

| Intestinal stricture without a mass | 4 (13.3) |

| Not definite | 3 (10.0) |

| Colonoscopy | |

| Eccentric wall thickening without mucosal change | 8 (26.7) |

| Eccentric wall thickening with mucosal change | 8 (26.7) |

| Normal | 4 (13.3) |

| Not evaluated | 10 (33.3) |

| Colonoscopic biopsy | |

| Inflammation | 6 (20.0) |

| Endometriosis | 4 (13.3) |

| Adenoma | 2 (6.7) |

| Normal mucosa | 1 (3.3) |

| Not evaluated | 17 (56.7) |

Thirteen patients (43.3%) had an initial diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis according to the results of preoperative evaluations (Table 3). The remaining 17 patients (56.3%) were misdiagnosed as having other diseases. The most common misdiagnosis was submucosal tumor in the large intestine (n = 8, 26.7%), followed by malignancies of the colon/rectum (n = 3, 10.0%) and ovary (n = 3, 10.0%).

| Preoperative diagnosis | n (%) |

| Pelvic endometriosis | 13 (43.3) |

| Rectosigmiod endometriosis | 9 (30.0) |

| Rectovaginal endometriosis | 2 (6.7) |

| Ovarian endometrioma | 2 (6.7) |

| Malignancy | 7 (23.3) |

| Colorectal cancer | 3 (10.0) |

| Ovarian cancer | 3 (10.0) |

| Small intestinal cancer | 1 (3.3) |

| Other disease | 10 (33.3) |

| Colorectal submucosal tumor | 8 (26.7) |

| Crohn’s disease with intestinal stricture | 1 (3.3) |

| Postoperative adhesion of the small intestine | 1 (3.3) |

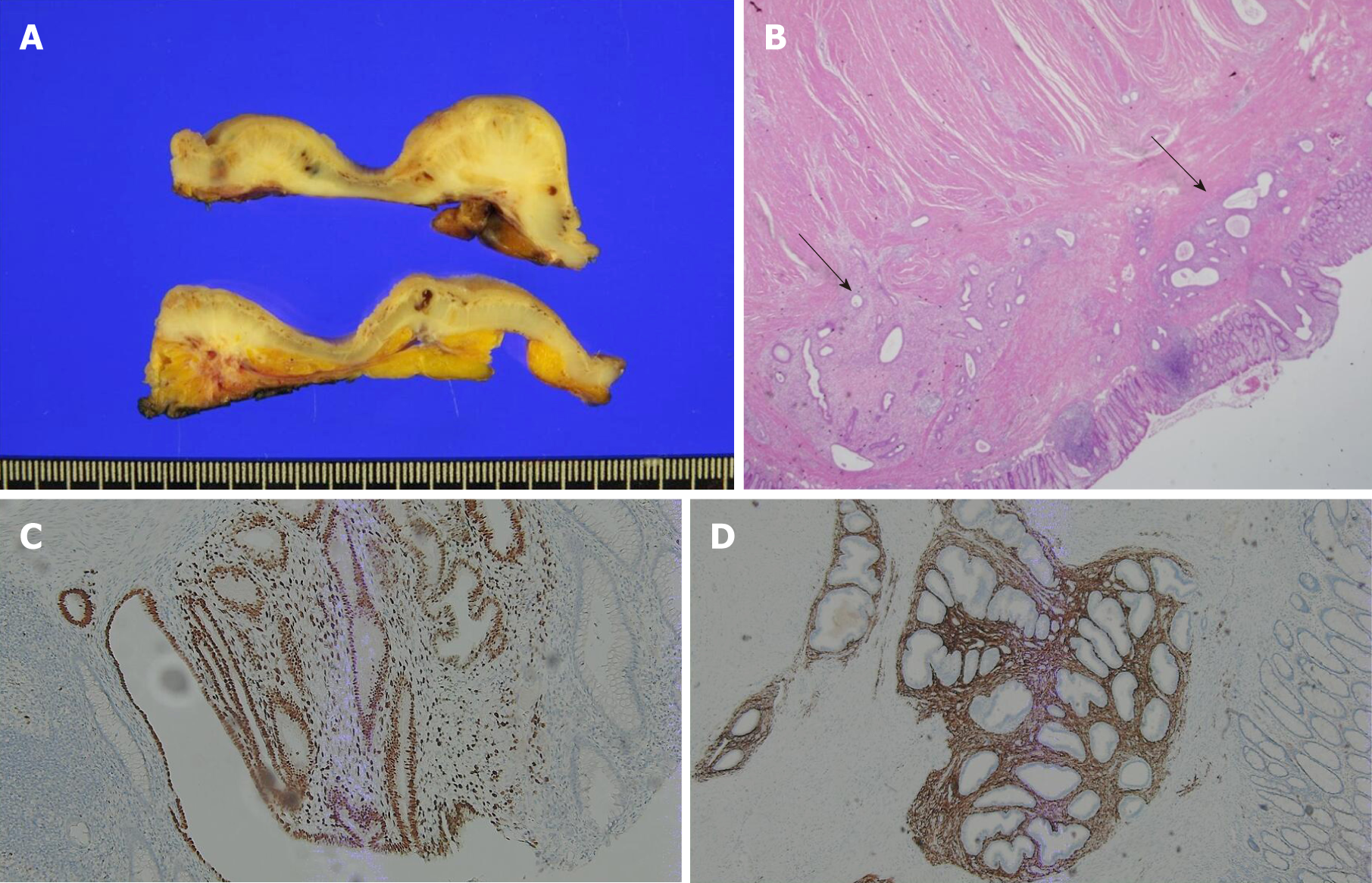

Intestinal endometriosis most frequently occurred in the sigmoid colon/rectum (n = 25, 83.3%) (Table 4). En bloc resections were performed including the bowel and other involved pelvic organs. Anterior resection and low anterior resection of the colon and rectum were performed in most patients (n = 25, 83.3%), whereas gynecologic operations were also performed in 15 patients (50.0%). Ureteroureterostomy was performed in 1 patient because of ureteric invasion of endometriosis inducing hydroureteronephrosis (Table 5). Figure 4A shows the gross specimen sections from a patient with endometriosis at the rectosigmoid colon. The endometriotic nodule caused thickening of the bowel wall and mucosal changes. Figure 4B shows the microscopic findings of this patient. Several endometrial glands were embedded in the submucosal layer, and foci of dense fibrosis surround the glands. The glands infiltrate the muscularis propria with an irregular margin. CD10 and ER (estrogen receptor) were positive as results of immunohistochemical staining and these results supported the diagnosis of this patient (Figure 4C and D).

| Location | n (%) |

| Rectum | 19 (63.3) |

| Sigmoid colon | 6 (20.0) |

| Ileum | 3 (10.0) |

| Cecum | 2 (6.7) |

| Operations | n (%) |

| Type of intestinal operation | |

| Low anterior resection | 15 (50.0) |

| Anterior resection | 10 (33.3) |

| Ileocecal resection | 3 (10.0) |

| Cecectomy | 1 (3.3) |

| Resection and anastomosis of the small intestine | 1 (3.3) |

| Type of combined operation | |

| TAH ± SO | 7 (23.3) |

| Ovarian cystectomy | 4 (13.3) |

| SO | 3 (10.0) |

| Posterior vaginectomy | 1 (3.3) |

| Ureteroureterostomy | 1 (3.3) |

| None | 14 (46.7) |

Complications within 30 d after the operation occurred in 7 (23.3%) patients: Pelvic abscess in 3 patients, paralytic ileus in 3 patients, and acute pyelonephritis in 1 patient (Table 6). Of these patients, 5 (16.7%) were treated with conservative management (CDC grade I–II) and 2 (6.7%) required intervention to manage the complication of fluid collection in the pelvic cavity (CDC grade IIIa). No patient had severe complications of CDC grade IIIb or more. Only 1 patient experienced recurrence at 3 years and 4 mo after the operation, and underwent bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for recurrence of endometrioma of the ovary. Median follow-up period after operation for intestinal endometriosis was 24 mo (0-128).

| Complication | n (%) | Clavien-Dindo classification | |||

| I | II | IIIa | IIIb | ||

| Pelvic abscess | 3 (10.0) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Paralytic ileus | 3 (10.0) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Acute pyelonephritis | 1 (3.3) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 7 (23.3) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

Intestinal endometriosis mostly presents with symptoms mimicking other diseases; thus, it is difficult to diagnose preoperatively. Screening techniques including CT and colonoscopy have limited values in the diagnosis because the disease invades inwards from the serosa and the mucosa remains uninvolved in the majority of cases. CT is an important modality as the first-line screening tool for identifying endometriomas and mapping multifocal lesions. However, our data showed that the incidence of intestinal endometriosis without a mass on CT images was 23.3%, and all of these cases were misdiagnosed as other diseases. In addition, although CT might reveal bowel wall thickening with the main lesions, it is not sufficient to diagnose intestinal endometriosis because evaluations of the invaded bowel wall or the characteristics of the mass cannot be exactly performed with CT images.

MRI is one of the most commonly used techniques for this purpose. A contrast-enhanced mass or hyperintense foci on T1-weighted MRI strongly suggest the presence of hemorrhagic foci secondary to endometriosis[1]. The sensitivity and specificity of MRI in detecting pelvic endometriosis is around 90%[1,2]. Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) may identify the presence of pelvic endometriosis with a relatively high accuracy (sensitivity, 83%; specificity, 94%) and help in estimating the depth of infiltration of the nodules in the intestinal wall[8]. In our cases initially diagnosed as pelvic endometriosis (13 cases), MRI and TVUS were used in 6 cases (46.1%) and 11 cases (84.6%), respectively. On the other hand, in our misdiagnosed cases (17 cases), MRI and TVUS were performed in only 3 cases (17.6%) and 4 cases (23.5%), respectively. Thus, in cases that intestinal endometriosis is suspicious, further evaluation using MRI and TVUS is important to diagnose intestinal endometriosis preoperatively. In our institute, we prefer MRI plus TVUS because they are relatively convenient modalities to understand the extent of disease and depth of invasion. However, since TVUS depends on the experience of the operator, other modalities such as MR-enterography and red-blood cell scintigraphy can be good alternatives with more than 90% of sensitivity[9,10]. MR-enterography especially enables to figure out details of small bowel involvement. Thus, tailored choice of modality is also important to diagnosis intestinal endometriosis preoperatively.

In our cases, the diagnostic accuracy of colonoscopy was very low (13.3%). Although colonoscopy is the first-line test in the evaluation of colonic bleeding, it is of little use in the diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis, because infiltration of the lesion into the mucosa is rare[11]. The endoscopic findings of colorectal endometriosis were narrowing, bulging into the lumen, and sometimes polyps or mucosal change with erythema and granularity[12]. These nonspecific findings of colonoscopy and biopsy of only the superficial layers make the diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis more difficult.

Evaluation of the operative history of patients has an important role in the diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis. In our study, about 13 patients (41.9%) had a history of pelvic surgery including cesarean section and hysterectomy. The positive correlation between a previously operated pelvis and endometriosis has been reported previously in other studies[13]. Although the mechanism is not known well, endometrial cells are believed to be incidentally implanted into the peritoneum during pelvic surgery, which can develop into pelvic endometriosis. In our study, intestinal endometriosis occurred after hysterectomy in 4 cases. Endometriosis can occur even after hysterectomy if the function of the ovary is preserved or hormone replacement therapy is used after hysterectomy because the remnant endometriosis of microscopic foci or deeply infiltrated lesions may develop into the disease[14]. In our cases, the ovary was preserved in all 4 patients with a history of hysterectomy at the time of diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis.

Previous treatment for endometriosis is also an important factor in diagnosing intestinal endometriosis. The overall recurrence rate of endometriosis is reported to be up to 67%[15]. The recurrence of endometriosis after bowel resection has been reported in 4.7%-25% of cases during the follow-up period of > 2 years[5]. In our cases, 10 patients (33.3%) had a history of treatments for endometriosis at the time of diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis. In addition, 1 patient underwent reoperation for pelvic endometriosis (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) at 39 mo after bowel surgery for intestinal endometriosis. Several studies demonstrated that the recurrence risk increases if the lesions are not completely removed during the initial surgery, and that recurrence tends to occur at the same location[16]. Particularly in deep infiltrating endometriosis, the recurrence rate is higher with lymph node involvement or lymphovascular invasion[17]. Thus, intestinal endometriosis should be considered if patients presenting with abdominal symptoms have a history of endometriosis.

Previous treatments for other diseases can also mislead the diagnosis of patients with intestinal endometriosis. In our cases, a patient with acute abdominal symptoms and a stricture of the terminal ileum in CT images was diagnosed as having an acute aggravation of Crohn’s disease due to the history of treatment for Crohn’s disease. The patient underwent ileocecal resection, and the pathologic diagnosis was intestinal endometriosis at the terminal ileum. Another patient with repeated pelvic surgeries showed symptoms of obstruction. Small-bowel obstruction was identified on CT images, and postoperative adhesion of the small intestine was diagnosed. However, after small-bowel resection and anastomosis, endometriosis was proven to be the main cause of the abdominal symptoms.

We also examined postoperative complications of patients. Paralytic ileus and pelvic abscess were the main complications after surgery, and most of them were managed conservatively. Complications related to anastomosis, such as rectovaginal fistula, anastomotic leakage, and pelvic abscess, are reported as the major postoperative complications after surgical treatment for intestinal endometriosis, and their prevalence was highly variable among studies[5]. Most of the complications were related to combined resection of other pelvic organs such as the bladder, ureter, ovary, and uterus. Additionally, functional problems including voiding difficulty and sexual dysfunction were also reported as postoperative complications after surgical treatment for rectal endometriosis[18]. Thus, a diverting stoma should be considered in case of en bloc resection of other pelvic organs with the rectum to avoid anastomotic problems. Moreover, autonomic nerve preservation is also required during dissection of the rectum from the pelvis to prevent functional problems related to pelvic denervation.

As we mentioned above, the recurrence rate of endometriosis is relatively high. To prevent recurrence, it is important to remove all endometriotic tissue while preserving fertility[19]. There are various surgical treatment methods for intestinal endometriosis, including resection and anastomosis, discoid resection, and superficial shaving[5]. No study about the postoperative results of different surgical methods has been reported yet. Many authors have demonstrated that incomplete excision is a major cause of clinical recurrence; thus, en bloc resection with anastomosis is recommended to minimize recurrence[20]. Hormonal treatments for intestinal endometriosis cannot be offered to all women because they inhibit ovulation and may not be effective in cases with > 60% stenosis of the bowel lumen[2]. Postoperative hormonal therapy is considered effective in prolonging the interval between surgery and the first recurrence by maintaining the minimal disease state[21]. However, it is known to be ineffective in eliminating residual disease. In our study, it was not possible to examine the incidence of malignant transformation of endometriosis, because patients diagnosed with intestinal endometriosis incidentally after surgeries for malignancy were excluded. It is rare but endometriosis is known to have a malignant potential in less than 1%[22]. More careful surveillance should be considered to the patients with potentials such as repeated or rapid progression or mural nodules to monitor a malignant transformation of endometriosis[23].

There are several limitations to this study coming from a retrospective review of pathologic reports. In our institution, the number of total patients who underwent surgical treatments for endometriosis was 1205 during the study period, thus the rate of intestinal endometriosis was 2.5% (30/1205). This is relatively low compared with other studies about intestinal endometriosis. Actually, this study mainly focused on the surgical cases of intestinal endometriosis, thus this rate reflected only surgical treatments for intestinal endometriosis. However, as previously mentioned above, intestinal endometriosis without severe symptoms can be initially managed with medical treatments and these patients were omitted from our study. Additionally, although en bloc resection is a principle for surgical treatment of pelvic endometriosis, the gynecologic surgeons in our institution showed a tendency to avoid surgical resection of the intestinal tract in some cases of superficial involvement of intestinal tract. These cases could not be included in our study. Therefore, the prevalence of intestinal endometriosis could not be exactly assessed with our data. Secondly, exact definitions of preoperative symptoms could not be established because of the insufficient description of preoperative symptoms in our electrical medical records. We tried to gather exact information about initial symptoms, however, some of them were not enough to identify details of symptoms, such as degree, duration and location. Nevertheless, this study can be meaningful, because it suggests to colorectal surgeons that the intestinal endometriosis should be considered if female patients with ambiguous results of preoperative evaluations show severe symptoms requiring surgical treatment.

In conclusion, the clinical characteristics of intestinal endometriosis can mimic those of various intestinal diseases. Intestinal endometriosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of women of reproductive age who have ambiguous symptoms and signs, as well as nonspecific radiologic and/or endoscopic findings.

The intestinal endometriosis is a disease that endometrial tissue involves the small or large intestine. Endometriosis is relatively common disease, but intestinal endometriosis is very rare and it is difficult to diagnose preoperatively.

A young woman who was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and under medical treatment for about 3 years at our hospital had suffered severe abdominal paint at right lower quadrant. We had found severe stricture of terminal ileum at computed tomography (CT) images. We had misdiagnosed her as acute phase of Crohn’s disease, but the pathologic result was intestinal endometriosis. After that, we reviewed similar cases in our institution and identified there was several misdiagnosed cases before operations. We had also searched similar studies, but not enough information was acquired with their clinical characteristics.

We aimed to evaluate the clinical characteristics of misdiagnosed cases before surgery and tried to suggest ways to reduce those cases.

We retrospectively reviewed medical records of patients who had been diagnosed with intestinal endometriosis from their surgical specimens. Fifty patients were identified and 20 cases were excluded because the diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis was made incidentally during surgical resection for other pathologies. A total of 30 patients were included in this study and their clinical characteristics including age, history of abdominal surgery or endometriosis were evaluated. Clinical presentation, CT imaging, endoscopic findings were also evaluated and preoperative diagnosis, locations of lesions, types of bowel surgeries, and combined operations were analyzed.

According to preoperative evaluations, 13 patients (43.3%) had an initial diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis and 17 patients (56.6%) were misdiagnosed as having other diseases. Only 4 patients (13.3%) had a diagnosis of endometriosis based on endoscopic biopsy findings. The most common misdiagnosis was submucosal tumor in the large intestine (n = 8, 26.7%), followed by malignancies of the colon/rectum (n = 3, 10.0%) and ovary (n = 3, 10.0%).

Symptoms of intestinal endometriosis mimic various intestinal diseases, thus it is difficult to diagnose preoperatively. Intestinal endometriosis should be considered when women of reproductive age have ambiguous symptoms and signs with preoperative evaluations.

It will be meaningful to study about more long term results of patients with intestinal endometriosis and their potency of malignant formation.

Date sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Osawa S, Seow-Choen F, Sipos F, Jiang QP S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Wolthuis AM, Meuleman C, Tomassetti C, D'Hooghe T, de Buck van Overstraeten A, D'Hoore A. Bowel endometriosis: colorectal surgeon's perspective in a multidisciplinary surgical team. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:15616-15623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ferrero S, Camerini G, Maggiore ULR, Venturini PL, Biscaldi E, Remorgida V. Bowel endometriosis: Recent insights and unsolved problems. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;3:31-38. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Remorgida V, Ferrero S, Fulcheri E, Ragni N, Martin DC. Bowel endometriosis: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62:461-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Campagnacci R, Perretta S, Guerrieri M, Paganini AM, De Sanctis A, Ciavattini A, Lezoche E. Laparoscopic colorectal resection for endometriosis. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:662-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Meuleman C, Tomassetti C, D'Hoore A, Van Cleynenbreugel B, Penninckx F, Vergote I, D'Hooghe T. Surgical treatment of deeply infiltrating endometriosis with colorectal involvement. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:311-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Seaman HE, Ballard KD, Wright JT, de Vries CS. Endometriosis and its coexistence with irritable bowel syndrome and pelvic inflammatory disease: findings from a national case-control study--Part 2. BJOG. 2008;115:1392-1396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yantiss RK, Clement PB, Young RH. Endometriosis of the intestinal tract: a study of 44 cases of a disease that may cause diverse challenges in clinical and pathologic evaluation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:445-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Goncalves MO, Podgaec S, Dias JA, Gonzalez M, Abrao MS. Transvaginal ultrasonography with bowel preparation is able to predict the number of lesions and rectosigmoid layers affected in cases of deep endometriosis, defining surgical strategy. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:665-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rousset P, Peyron N, Charlot M, Chateau F, Golfier F, Raudrant D, Cotte E, Isaac S, Réty F, Valette PJ. Bowel endometriosis: preoperative diagnostic accuracy of 3.0-T MR enterography--initial results. Radiology. 2014;273:117-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Demirel F, Koca G, Demirel K, Aydogmus H, Korkmaz M, Gokmen B. Labeled red blood cell scintigraphy in the non-invasive diagnostics of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:S202. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim KJ, Jung SS, Yang SK, Yoon SM, Yang DH, Ye BD, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Kim JH. Colonoscopic findings and histologic diagnostic yield of colorectal endometriosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:536-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bergqvist A. Different types of extragenital endometriosis: a review. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1993;7:207-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Peterson CM, Johnstone EB, Hammoud AO, Stanford JB, Varner MW, Kennedy A, Chen Z, Sun L, Fujimoto VY, Hediger ML, Buck Louis GM; ENDO Study Working Group. Risk factors associated with endometriosis: importance of study population for characterizing disease in the ENDO Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:451.e1-451.11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rizk B, Fischer AS, Lotfy HA, Turki R, Zahed HA, Malik R, Holliday CP, Glass A, Fishel H, Soliman MY, Herrera D. Recurrence of endometriosis after hysterectomy. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2014;6:219-227. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Selçuk İ, Bozdağ G. Recurrence of endometriosis; risk factors, mechanisms and biomarkers; review of the literature. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2013;14:98-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Guo SW. Recurrence of endometriosis and its control. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:441-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 403] [Cited by in RCA: 472] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Randall GW, Gantt PA, Poe-Zeigler RL, Bergmann CA, Noel ME, Strawbridge WR, Richardson-Cox B, Hereford JR, Reiff RH. Serum antiendometrial antibodies and diagnosis of endometriosis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;58:374-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Landi S, Ceccaroni M, Perutelli A, Allodi C, Barbieri F, Fiaccavento A, Ruffo G, McVeigh E, Zanolla L, Minelli L. Laparoscopic nerve-sparing complete excision of deep endometriosis: is it feasible? Hum Reprod. 2006;21:774-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chopin N, Vieira M, Borghese B, Foulot H, Dousset B, Coste J, Mignon A, Fauconnier A, Chapron C. Operative management of deeply infiltrating endometriosis: results on pelvic pain symptoms according to a surgical classification. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12:106-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fedele L, Bianchi S, Zanconato G, Bettoni G, Gotsch F. Long-term follow-up after conservative surgery for rectovaginal endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1020-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Seong SJ, Kim D, Lee KH, Kim TJ, Chung HH, Chang SJ, Lee EJ. Role of Hormone Therapy After Primary Surgery for Endometrioma: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. Reprod Sci. 2016;23:1011-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Heaps JM, Nieberg RK, Berek JS. Malignant neoplasms arising in endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:1023-1028. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Takeuchi M, Matsuzaki K, Uehara H, Nishitani H. Malignant transformation of pelvic endometriosis: MR imaging findings and pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2006;26:407-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |