Published online Dec 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i24.4292

Peer-review started: June 5, 2019

First decision: October 24, 2019

Revised: November 22, 2019

Accepted: November 26, 2019

Article in press: November 26, 2019

Published online: December 26, 2019

Processing time: 205 Days and 6.1 Hours

Paragonimiasis is a food-borne parasitic infection caused by lung flukes of the genus Paragonimus. Although the most common site of infection is the pleuropulmonary area, the parasite can also reach other parts of the body on its journey from the intestines to the lungs, ending up in locations such as the brain, abdomen, skin, and subcutaneous tissues. Ectopic paragonimiasis is difficult to diagnose due to the rarity of this disease.

Here, we report a rare case of simultaneous breast and pulmonary paragonimiasis in a woman presenting painless breast mass and lung nodule with a history of eating raw trout. To confirm the diagnosis, serologic testing and tissue confirmation of the breast mass were performed. The patient was treated with surgical resection of the mass and praziquantel medication.

Ectopic paragonimiasis is difficult to diagnose due to the rarity of this disease. Thus, thorough history-taking and clinical suspicion of parasitic infection are important.

Core tip: Paragonimiasis is a parasitic infection caused by lung flukes of genus Paragonimus. Paragonimiasis is an important food-borne worldwide disease. It has been estimated that 22.8 million people worldwide are at risk of paragonimiasis. Here we present a rare case of simultaneous breast and pulmonary paragonimiasis in a woman presenting with a painless breast mass and a lung nodule, who has a history of eating raw trout. To confirm the diagnosis, serologic testing and tissue confirmation of the breast mass were performed. The patient was treated with surgical resection of the mass and praziquantel medication. Because of the rarity of ectopic paragonimiasis, history-taking and clinical suspicion of parasitic infection are important.

- Citation: Oh MY, Chu A, Park JH, Lee JY, Roh EY, Chai YJ, Hwang KT. Simultaneous Paragonimus infection involving the breast and lung: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(24): 4292-4298

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i24/4292.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i24.4292

Paragonimiasis is a parasitic infection caused by lung flukes of genus Paragonimus. Paragonimus rudis was first reported in the lung of an otter by Diesing in 1885. Since then, 43 species of Paragonimus have been reported. Of many different species of Paragonimus, only 8 species are known to develop and cause disease in man, the most common one being Paragonimus westermani[1]. Paragonimiasis is an important food-borne worldwide disease. It has been estimated that 22.8 million people worldwide are at risk of Paragonimiasis. Human beings are infected by ingesting raw or undercooked crabs, crayfish, and shrimps[2]. The parasites produce toxic substances, which cause aseptic inflammation or granulomatous reaction[3]. Pulmonary paragonimiasis is the most common clinical manifestation. Patients generally present with chronic productive cough and blood-tinged sputum. They may also present hemoptysis, chest pain, and dyspnea, although these symptoms are less frequent. The adult Paragonimus wanders around until it reaches the lungs, but during this migration process, other parts of the body such as the brain, abdomen, skin, heart, and subcutaneous tissues can also be involved[3,4]. Only two cases of breast paragonimiasis have been reported so far[5,6]. There is only one reported case of Paragonimus infection affecting two separate organs[7]. We report a rare case of simultaneous Paragonimus infection involving the breast and lung with review of related literature.

A 43-year-old female patient presented to the hospital with a painless mass of the left breast.

The mass was palpable one month prior to the visit. She had already done a breast sonography at a local clinic. She was recommended to do a biopsy for the breast mass. She transferred to our hospital, a larger tertiary care hospital, for further evaluation. The patient did not remember consuming crabs or crayfish. However, she did mention that she had eaten raw trout recently.

The patient had no underlying disease.

The patient denied any family history.

On physical examination, the palpable mass of the left breast was about 1.5 cm in diameter, well-defined, and freely moveable. There was a small amount of nipple discharge. There was no evidence of skin color change or skin retraction.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was initiated. Results came out positive for paragonimiasis.

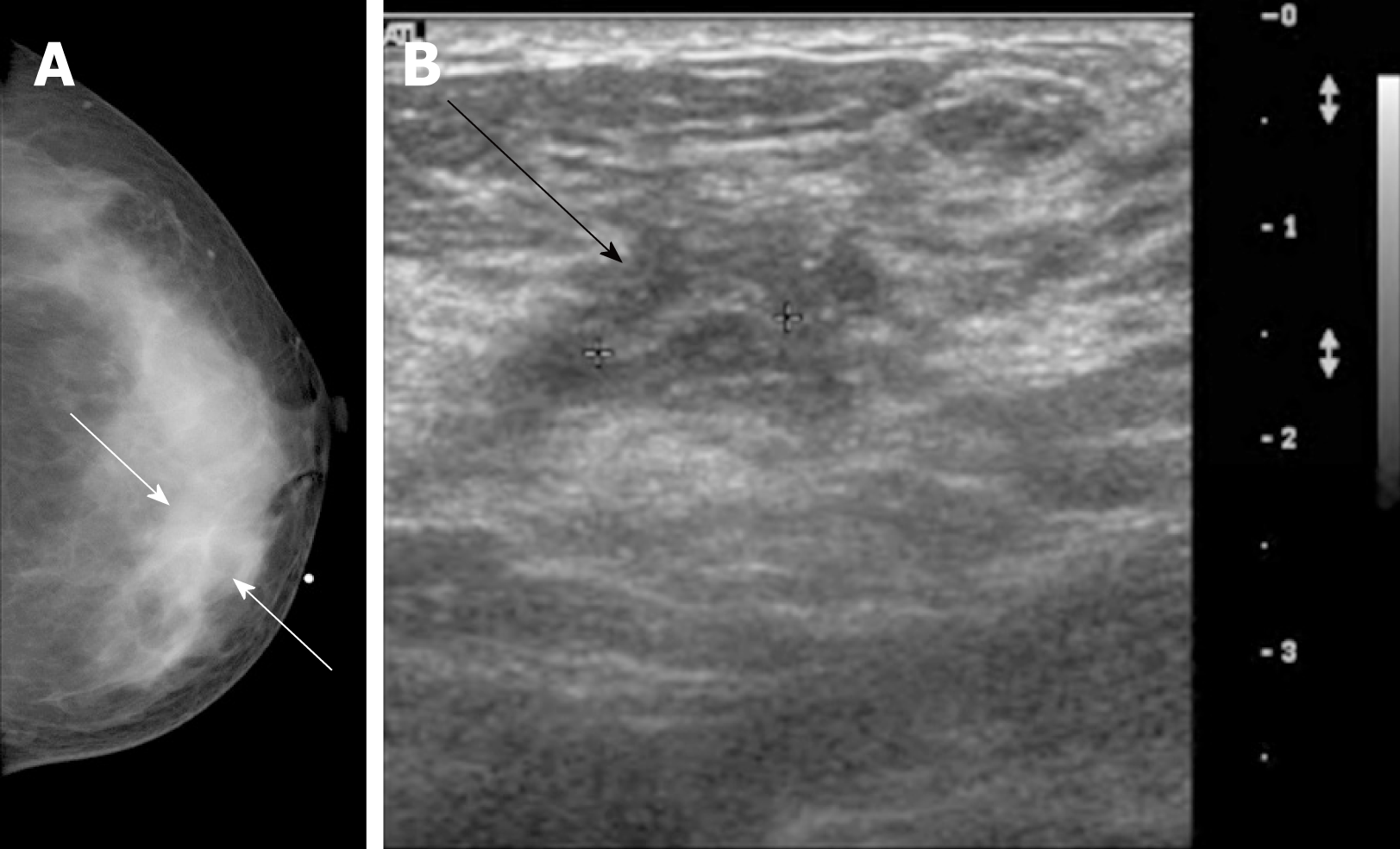

Mammogram showed an asymmetry at the palpable site of the left inner breast (Figure 1A). Ultrasonogram revealed 2 cm sized circumscribed cystic space connected to the nipple. A 0.2 cm sized hypoechoic irregular tubular mass was demonstrated within the cystic cavity (Figure 1B). This tubular structure was seen to be freely moving within the cavity.

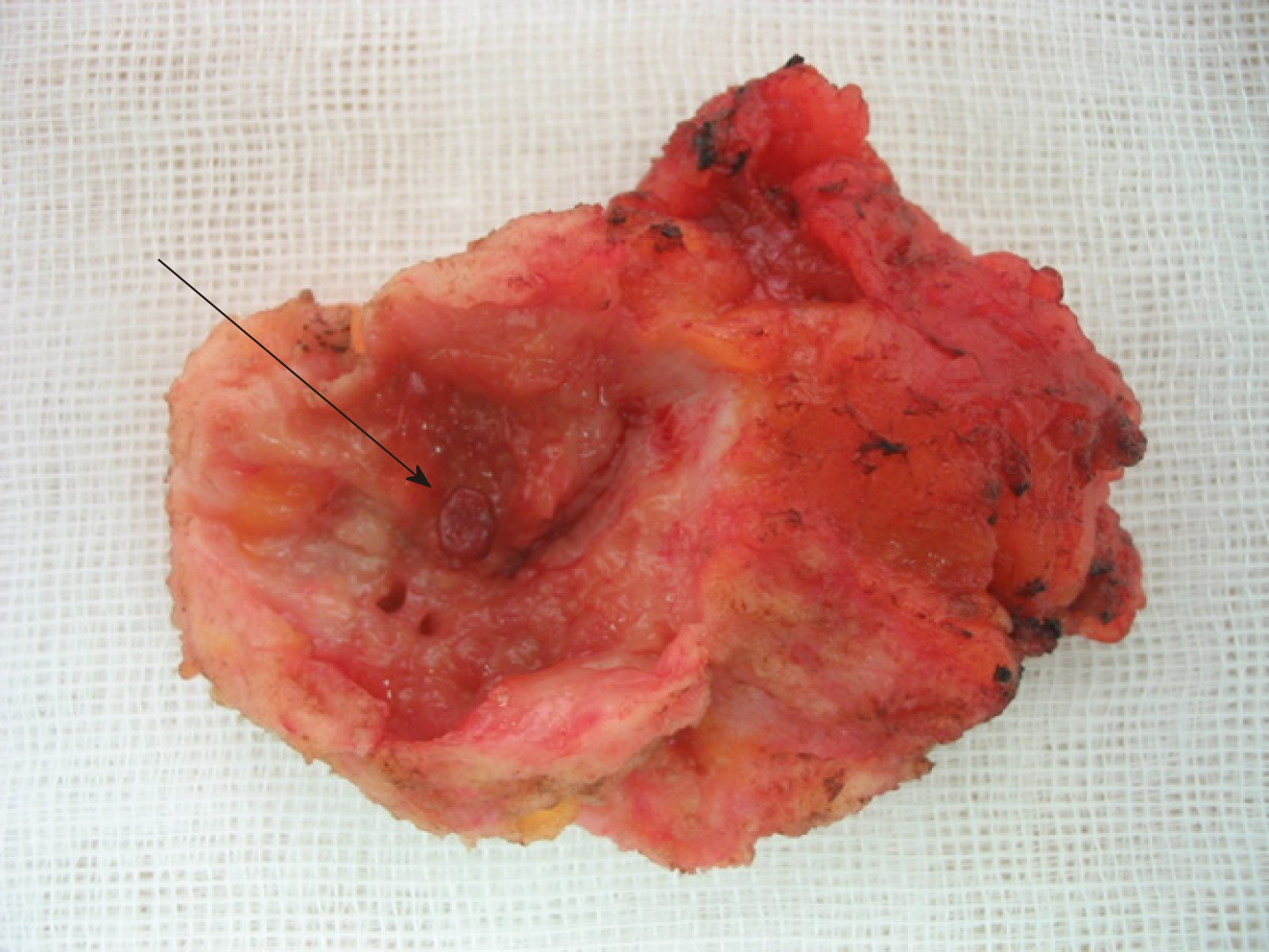

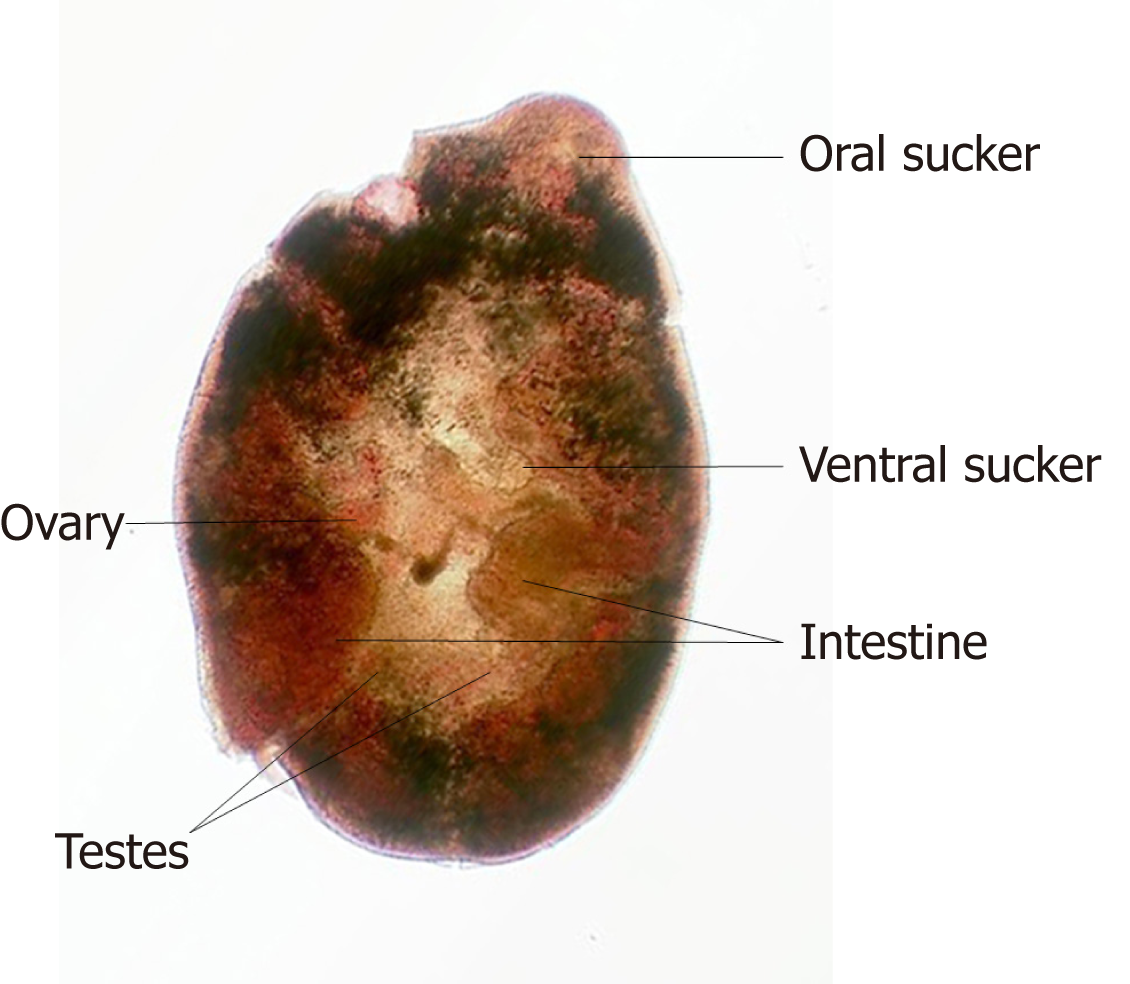

A parasitic infection was suspected and excisional biopsy of the breast mass was performed. Inside the excised soft tissue mass, there was a cystic lesion with an irregular inner wall that was grayish white in color with about 2.3 cm for the longest diameter (Figure 2). Inside this cystic lesion was a red, oval-shaped figure that was about 5 mm in longest diameter. It was suspected to be a parasite. This specimen was sent to the Department of Parasitology. It was confirmed to be Paragonimus westermani (Figure 3). The pathology of the left breast mass excluding the parasite itself showed chronic granulomatous inflammation with eosinophilic infiltration, dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, and features suggesting parasitic eggs.

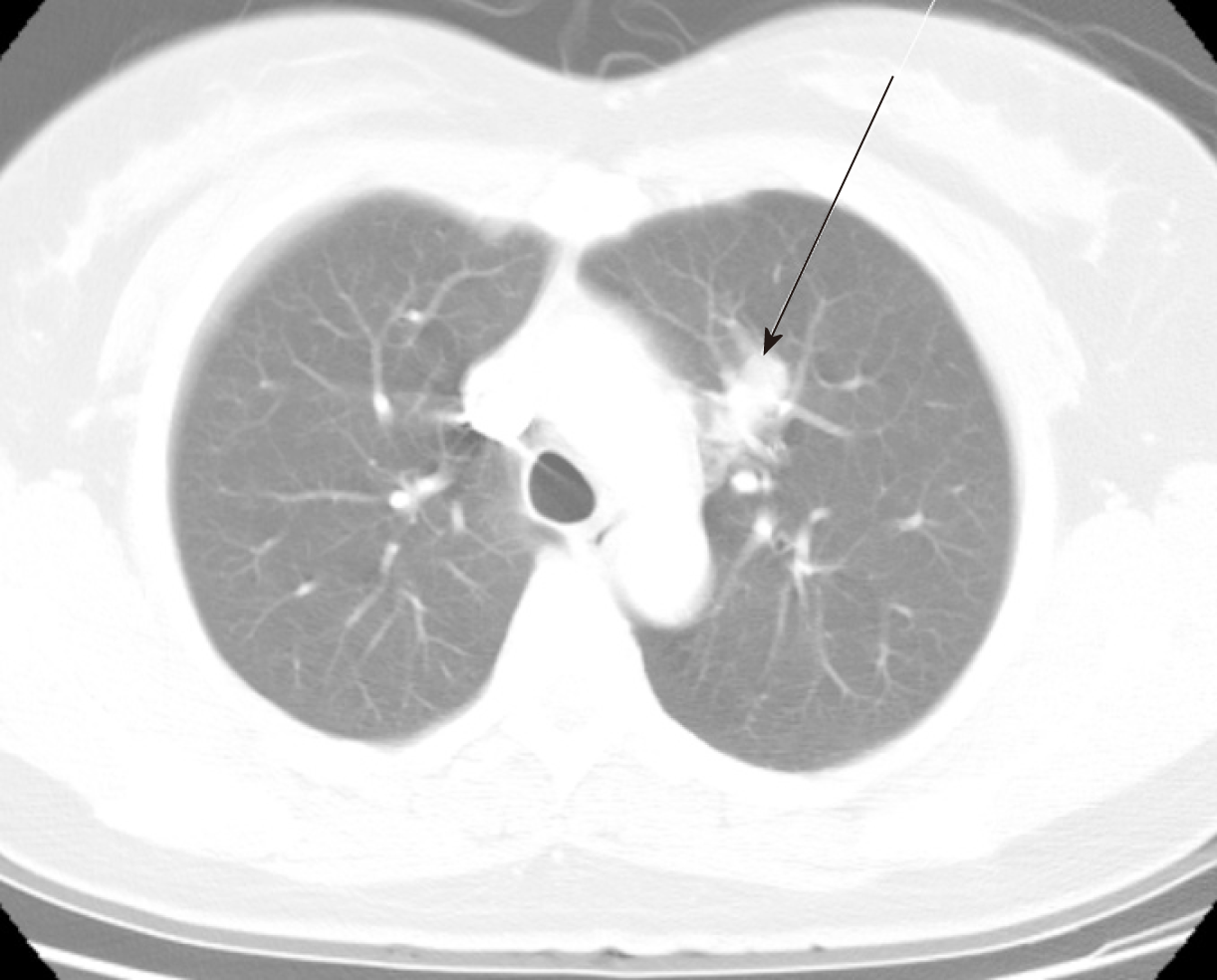

The patient was also referred to the Pulmonary Department of Internal Medicine. She complained of blood tinged sputum 3-4 wk prior to the visit. An 18 mm sized elongated nodule at left upper lobe of the lung was seen on chest computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 4). Clinically, this nodule was considered as a paragonimiasis-related nodule.

The final diagnosis of the presented case is paragonimiasis of the breast and lung.

The breast mass was excised and the patient was treated with praziquantel 25 mg/kg/d for 3 d.

The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful. Follow-up breast examinations and chest X-rays were normal.

Paragonimiasis is a food-borne parasitic disease caused by Paragonimus species, the most common one being Paragonimus westermani. These parasites are widely distributed worldwide, especially in Asia, West-Central Africa, Central America, and South America[2]. The parasite causes pulmonary infections most of the time, although it sometimes causes extrapulmonary infections[1].

Adult worms of Paragonimus are usually encapsulated in the lungs and sometimes in other organs of definite hosts, including humans and other mammals. Eggs produced by these worms can exit the pulmonary system through bronchioles. They can be coughed out or expelled through feces, ultimately ending up in freshwater ponds, streams, or rivers. Their miracidia can then hatch from eggs and enter their first intermediate hosts such as snails to develop into sporocysts, then radiae, and eventually cercariae. Crabs or crayfish can ingest the infected snail. Then cercariae can penetrate crustacean hosts to become metacercariae. Their definitive hosts are known to be infected by eating raw or undercooked crabs or crayfish. These metacercariae will ultimately grow into adult worms[8]. The patient in the reported case had a history of eating raw trout as a potential route of transmission.

When humans are infected, metacercariae can pass through the intestinal wall into the peritoneal cavity and through the diaphragm into the pleural cavity, eventually ending up in the lung parenchyma and finally grow into adult flukes[9]. On its journey to the lungs, the parasite can reach other locations of the body such as the brain, abdomen, skin, heart, and subcutaneous tissues[10]. The primary site of parasitic infection is the lung. Therefore, most patients present with respiratory symptoms such as cough, sputum, chest discomfort, and dyspnea. Subcutaneous paragonimiasis is rare compared to pulmonary and other ectopic manifestations. Its diagnosis is difficult due to rarity of the disease with various symptoms[9,11]. In the present case, paragonimiasis manifested both in pulmonary and extrapulmonary forms, presenting as a breast mass and a lung nodule.

Mammography and ultrasonography examinations were used to diagnose the breast mass in our patient. Mammography revealed limited information of the mass, but the ultrasonography was able to reveal a cystic cavity as well as the real time imaging of the moving worm inside. On the other hand, the lung nodule was diagnosed with a chest CT scan. The main features of pleuropulmonary paragonimiasis on chest CT scans are mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and subfissural or subpleural nodules[12]. Likewise, mediastinal lymph node enlargement was seen in our patient’s scan, and because the scan was performed after the pathological diagnosis of breast paragonimiasis, this nodule was clinically considered as a paragonimiasis-related nodule. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan would have also been a great diagnostic imaging tool, as it is a promising non-invasive parameter for the assessment of both breast masses and mediastinal masses[13]. However, MRI scan is expensive compared to other imaging tools, bringing to question its cost-effectiveness, because parasitic infection of the breast was well diagnosed with ultrasonography in this case.

ELISA test, an immunodiagnostic method that can detect and measure antibodies in the blood, is known to be both highly sensitive and specific for diagnosing paragonimiasis[9,14]. Infection by Paragonimus can be prevented by not eating raw or undercooked crabs and crayfish. Praziquantel is the first-line treatment for human paragonimiasis. It is proven to be highly effective[9,15,16]. To the best of our knowledge, only two cases of paragonimiasis of the breast have been reported so far[6,7]. Paragonimiasis was diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration biopsy in both cases and ELISA test was done only in one of these two cases. In both cases, patients were treated with praziquantel[6,7]. In our patient, biopsy by surgical resection as well as ELISA test were performed for the diagnosis. For treatment, she was also prescribed praziquantel.

Up to now, only one case has been reported of Paragonimus infection that simultaneously involved two separate organs[7]. In the mentioned case, a computed tomography scan of the patient revealed a pulmonary cavity lesion and an adrenal mass when he presented with hemotypsis. Both lesions were confirmed as Paragonimus infection by surgical resection[7]. Our patient also presented with lesions of two different organs, a breast mass and a lung nodule. She first presented with a breast mass. She was diagnosed and treated for breast paragonimiasis. It was only after the management of the breast mass that she was referred to the Pulmonology Department for intermittent symptom of blood tinged sputum and clinically diagnosed with pulmonary paragonimiasis for the lung nodule seen on computed tomography scan. The breast mass was confirmed by surgical resection as a Paragonimus infection and the lung nodule was clinically considered as a paragonimiasis-related nodule. This is a first case of extrapulmonary paragonimiasis manifesting as a breast mass with simultaneous pulmonary Paragonimus infection.

The patient presented with a painless breast mass and a lung nodule as seemingly two unrelated manifestations. Thus, differential diagnosis of a painless breast mass along with a pulmonary nodule is important, especially to rule out malignancy and metastasis. Because of the rarity of subcutaneous paragonimiasis, clinical suspicion of parasitic infection is important and proper history-taking is of essence.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: El-Razek AA S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Choi DW. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in Korea. Kisaengchunghak Chapchi. 1990;28 Suppl:79-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sah R, Khadka S. Case series of paragonimiasis from Nepal. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2017;2017:omx083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abdel Razek AA, Watcharakorn A, Castillo M. Parasitic diseases of the central nervous system. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2011;21:815-841, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Roy P, Praharaj AK, Dubey S. An unusual case of human paragonimiasis. Med J Armed Forces India. 2015;71:S60-S62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fogel SP, Chandrasoma PT. Paragonimiasis in a cystic breast mass: case report and implications for examination of aspirated cyst fluids. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;10:229-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jun SY, Jang J, Ahn SH, Park JM, Gong G. Paragonimiasis of the breast. Report of a case diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 2003;47:685-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kwon YS, Lee HW, Kim HJ. Paragonimus westermani infection manifesting as a pulmonary cavity and adrenal gland mass: A case report. J Infect Chemother. 2019;25:200-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu Q, Wei F, Liu W, Yang S, Zhang X. Paragonimiasis: an important food-borne zoonosis in China. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:318-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim MJ, Kim SH, Lee SO, Choi SH, Kim YS, Woo JH, Yoon YS, Kim KW, Cho J, Chai JY, Chong YP. A Case of Ectopic Peritoneal Paragonimiasis Mimicking Diverticulitis or Abdominal Abscess. Korean J Parasitol. 2017;55:313-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee CH, Kim JH, Moon WS, Lee MR. Paragonimiasis in the abdominal cavity and subcutaneous tissue: report of 3 cases. Korean J Parasitol. 2012;50:345-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kodama M, Akaki M, Tanaka H, Maruyama H, Nagayasu E, Yokouchi T, Arimura Y, Kataoka H. Cutaneous paragonimiasis due to triploid Paragonimus westermani presenting as a non-migratory subcutaneous nodule: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shim SS, Kim Y, Lee JK, Lee JH, Song DE. Pleuropulmonary and abdominal paragonimiasis: CT and ultrasound findings. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:403-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Abdel Razek AA, Soliman N, Elashery R. Apparent diffusion coefficient values of mediastinal masses in children. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:1311-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Imai J. Evaluation of ELISA for the diagnosis of paragonimiasis westermani. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1987;81:3-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ibáñez N, Jara C. Experimental paragonimiasias: therapeutical tests with praziquantel--first report. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1992;87 Suppl 1:107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kashida Y, Niiro M, Maruyama H, Hanaya R. Cerebral Paragonimiasis With Hemorrhagic Stroke in a Developed Country. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27:2648-2649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |