Published online Dec 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i24.4186

Peer-review started: September 5, 2019

First decision: October 24, 2019

Revised: October 31, 2019

Accepted: November 20, 2019

Article in press: November 20, 2019

Published online: December 26, 2019

Processing time: 110 Days and 23.5 Hours

The impact of resection margin status on long-term survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for patients with pancreatic head carcinoma remains controversial and depends on the method used in the histopathological study of the resected specimens. This study aimed to examine the impact of resection margin status on the long-term overall survival of patients with pancreatic head carcinoma after PD using the tumor node metastasis standard.

Consecutive patients with pancreatic head carcinoma who underwent PD at the Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital between May 2010 and May 2016 were included. The impact of resection margin status on long-term survival was retrospectively analyzed.

Among the 124 patients, R0 resection was achieved in 85 patients (68.5%), R1 resection in 38 patients (30.7%) and R2 resection in 1 patient (0.8%). The 1- and 3-year overall survival (OS) rates were significantly higher for the patients who underwent R0 resection than the rates for those who underwent R1 resection (1-year OS rates: 69.4% vs 53.0%; 3-year OS rates: 26.9% vs 11.7%). Multivariate analysis showed that resection margin status and venous invasion were significant risk factors for OS.

Resection margin was an independent risk factor for OS for patients with pancreatic head carcinoma after PD. R0 resection was associated with significantly better OS after surgery.

Core tip: This study aimed to examine the impact of resection margin status on the long-term overall survival of patients with pancreatic head carcinoma after pancreaticoduodenectomy using the tumor node metastasis standard. We found the resection margin was an independent risk factor for overall survival for patients with pancreatic head carcinoma after pancreaticoduodenectomy. R0 resection was associated with significantly better overall survival after surgery. It is suggested that surgeons should perform radical resection for patients with pancreatic head cancer as much as possible.

- Citation: Li CG, Zhou ZP, Tan XL, Gao YX, Wang ZZ, Liu Q, Zhao ZM. Impact of resection margins on long-term survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic head carcinoma. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(24): 4186-4195

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i24/4186.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i24.4186

Pancreatic carcinoma is well-known to have a poor prognosis, and R0 resection is the only treatment that provides the possibility of a cure. However, recurrence and metastasis are frequent after surgery, and the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate is approximately 6%[1,2]. The size and location of the tumor, resection margin status, lymphatic metastasis, neural invasion and tumor differentiation have been reported to positively correlate with postoperative long-term OS[3-5]. In recent years, the status of the resection margin has received much attention, but controversies still exist.

At present, there are no universally accepted histopathological examination procedures and standards used to evaluate resection margins for resected specimens after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD). The common criteria used to evaluate resection margins include tumor node metastasis (TNM) staging by the Union for International Cancer Control, the Japan Pancreas Society reporting guideline and the British Royal College of Pathologists standards[6-8]. While the definition used by the Union for International Cancer Control for R1 resection in the United States is microscopic evidence of tumor involvement of the resection margin[6], the British Royal College of Pathologists in the United Kingdom defined it as tumor involvement within 1 mm of the resection margin[8]. The impact of resection margin status on the long-term OS of patients differs with different evaluation procedures and standards. Some studies suggested that long-term OS for patients with R0 resection was significantly better than that for patients with R1 resection, while other studies indicated no significant differences[3-5,9-14].

This study aimed to investigate the impact of resection margin status on long-term OS in patients with pancreatic head carcinoma after PD based on the TNM standard.

Consecutive patients who underwent PD for pancreatic head carcinoma with curative intent by a single team of surgeons at the Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital between May 2010 and May 2016 were included in this study. Patients who died of complications in the perioperative period were not included because this study only focused on long-term OS. No patients received chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery. Patients with periampullary cancer, distal common bile duct cancer and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors were also excluded. Postoperative chemotherapy consisting of gemcitabine combined with abraxane and/or external irradiation was not routinely given even for patients with R1 resection. The pros and cons of chemotherapy were discussed with the patients, and only those who accepted chemotherapy received it.

Follow-up visits were conducted once every 1-2 mo in the first two years after surgery, once every 3-6 mo after surgery for years 3-5 and thereafter once every 6-12 mo. At each follow-up visit, after history taking and physical examination of the patient, laboratory blood tests and computed tomography were routinely performed. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital. The study was registered with ResearchRegistry.com, and the work has been reported in line with the STROCSS criteria[15].

The surgical procedures included pylorus-preserving PD and PD. Stents were routinely placed across the pancreaticojejunostomy for external drainage and were removed after 4 wk. The range of lymph node dissection included lymph node groups 5, 8, 12, 13, 14 and 17. When the tumor had invaded the portal/superior mesenteric vein, venous resection and reconstruction were performed in selected patients. No patients in this study had combined resection and reconstruction of the portal/superior mesenteric vein and superior mesenteric artery.

The resected specimens were fixed in formalin for 24-48 h. The surgeon and a pathologist identified the orientation of the resected specimen together. The pathologist then prepared and stained specimen slices and studied them microscopically. The resection margins of the specimens included the gastric, duodenal, choledochal and pancreatic cut ends and included the pancreatic groove for the portal/superior mesenteric vein and artery and the surrounding connective tissue layers of the pancreas. The cut ends of the portal/superior mesenteric vein were also studied in cases involving resection of these vessels. Based on the TNM standards, R1 resection indicated that residual tumor cells were present at any resection margin under microscopic examination, and R0 resection indicated no residual tumor at any resection margins[6].

The primary outcome was OS. The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was performed to evaluate the correlation between the resection margin status and categorical clinicopathological characteristics. Student's t test was used to evaluate continuous variables. OS was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and comparison of OS between subgroups was analyzed using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using the Cox proportional hazards regression model for potential prognostic factors of OS. All reported P values were 2-sided. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with the IBM SPSS statistical software, version 20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States).

For the 124 patients who underwent PD, the pathological diagnosis and tumor staging were based on the Eighth Version of the Union for International Cancer Control Classification (Table 1). The pathological diagnoses were pancreatic adenocarcinoma in 118 patients, pancreatic adenocarcinoma plus mucinous adenocarcinoma in 5 patients and pancreatic adenosquamous carcinoma in 1 patient. According to the TNM standards, 59 patients were in stage I, 57 patients were in stage II, 7 patients were in stage III, and 1 patient was in stage IV. The numbers of R0, R1 and R2 resections were 85, 38 and 1, respectively. The median survival time of all patients was 16 mo (range: 7-66 mo).

| Clinicopathologic features | Value |

| Mean age (range), yr | 59 (38-79) |

| Sex, M/F | 76/48 |

| Histopathologic diagnosis | |

| Well differentiated | 1 |

| Moderately differentiated | 74 |

| Poorly differentiated | 49 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 118 |

| Adenocarcinoma + mucinouscarcinoma | 5 |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 1 |

| Stage (Union International Contre le Cancer, 8th ed) | |

| I | 59 |

| II | 57 |

| III | 7 |

| IV | 1 |

| Resection margin status | |

| R0 | 85 |

| R1 | 38 |

| R2 | 1 |

| Median overall survival (range) in mo | 16 (7-66) |

The clinical and pathological characteristics of the patients in the R0 and R1 resection groups are summarized in Table 2. There were no significant differences in age, sex, tumor size, bile duct invasion, duodenal invasion, nerve plexus invasion, lymph node metastasis, venous invasion, frequency of postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy or mean hospital stay between the R0 (n = 85) and R1 groups (n = 38).

| No. patients | P value | ||

| R0 | R1 | ||

| Total patients | 85 | 38 | |

| Age in yr | 0.192 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 47 | 22 | |

| < 60 | 39 | 15 | |

| Sex | 0.719 | ||

| M | 53 | 23 | |

| F | 33 | 14 | |

| Tumor size in cm | 1.000 | ||

| < 2 | 6 | 3 | |

| ≥ 2 | 80 | 34 | |

| Bile duct invasion | 0.486 | ||

| Negative | 28 | 15 | |

| Positive | 58 | 23 | |

| Duodenal invasion | 0.480 | ||

| Negative | 40 | 12 | |

| Positive | 46 | 25 | |

| Nerve plexus invasion | 0.848 | ||

| Negative | 36 | 13 | |

| Positive | 50 | 24 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.562 | ||

| Negative | 54 | 21 | |

| Positive | 32 | 16 | |

| Venous invasion | 0.435 | ||

| Negative | 79 | 32 | |

| Positive | 7 | 5 | |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 0.180 | ||

| No | 45 | 25 | |

| Yes | 41 | 12 | |

| Postoperative radiotherapy | 0.354 | ||

| No | 67 | 44 | |

| Yes | 18 | 4 | |

| Operation blood loss in mL | 251.61 ± 173.94 | 299.23 ± 216.67 | 0.195 |

| Hospital stay in d | 16.70 ± 7.98 | 16.31 ± 5.65 | 0.786 |

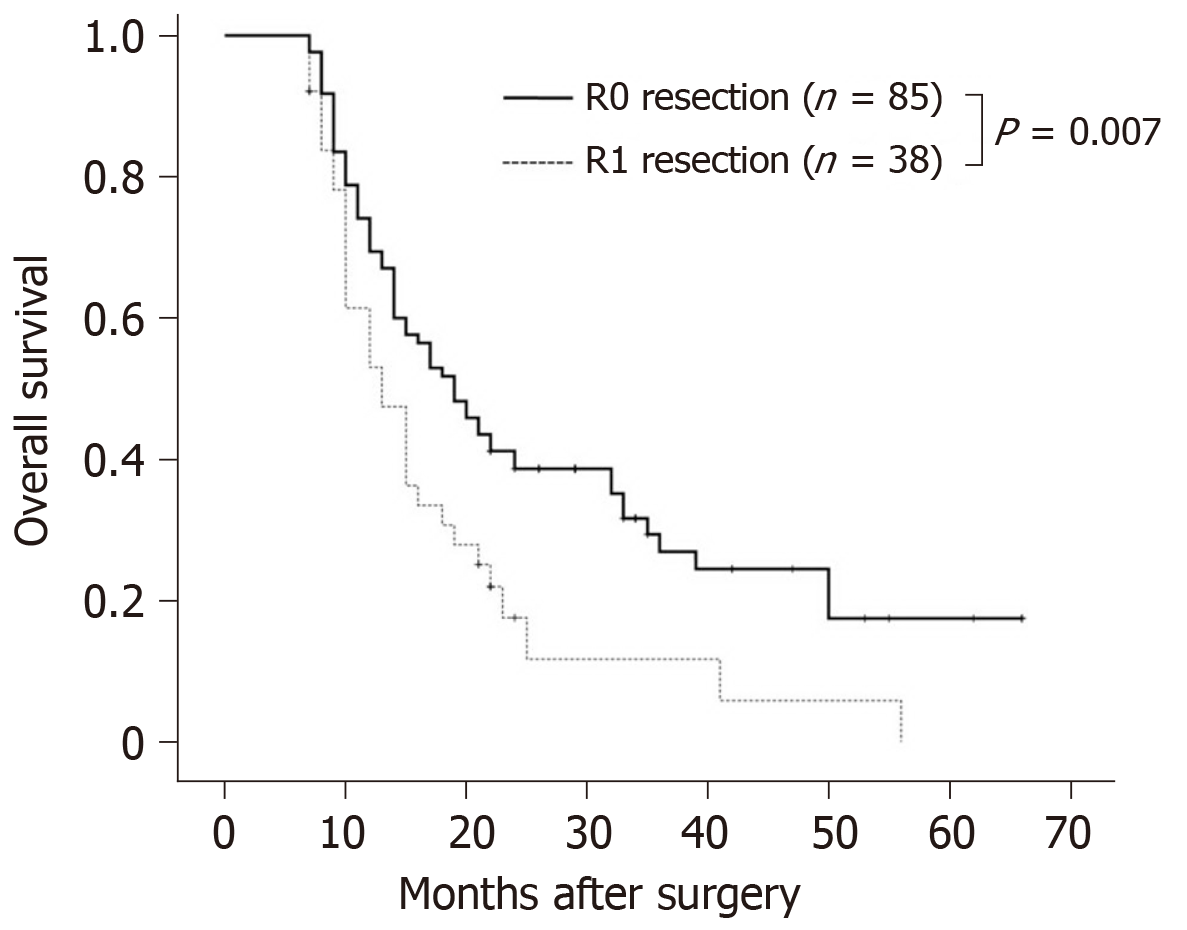

As the number of patients with R2 resection was small (n = 1), the patient was excluded from the survival analysis. The results of multivariate analysis on factors influencing OS are shown in Table 3. The mean OS of the 123 patients was 20.6 mo. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses and log-rank tests on the impact of factors on OS, including age, sex, tumor size, degree of differentiation, margin status, bile duct invasion, duodenal invasion, nerve plexus invasion, lymph node metastasis, venous invasion, postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy, intraoperative blood loss and average hospitalization time showed only R1 resection (hazard ratio = 1.773; 95% confidence interval: 1.149-2.736) and venous invasion (hazard ratio = 2.771; 95% confidence interval: 1.447-5.304) to be significantly correlated with a decrease in postoperative OS. The mean OS rates in patients who underwent R0 and R1 resections were 22.8 mo and 15.5 mo, respectively (χ2 = 7.287, P = 0.007) (Figure 1). The 1-year and 3-year survival rates were significantly higher in patients who underwent R0 resection than the rates in those who underwent R1 resection (1-year survival rate: 69.4% vs 53.0%; 3-year survival rate: 26.9% vs 11.7%). The mean OS rates in patients without and with venous invasion were 21.5 and 11.6 mo, respectively (χ2 = 10.983, P = 0.001).

| Prognostic variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age in yr | ||||||

| ≥ 60 | 1.000 | - | 0.218 | |||

| < 60 | 0.770 | 0.508-1.167 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| M | 1.000 | - | 0.959 | |||

| F | 0.995 | 0.807-1.226 | ||||

| Tumor size in cm | ||||||

| ≥ 2 | 1.000 | - | 0.140 | |||

| < 2 | 0.507 | 0.206-1.251 | ||||

| Differentiation degree | ||||||

| Poor | 1.000 | 0.791 | ||||

| Well + Middle | 0.944 | 0.619-1.442 | ||||

| Margin status | ||||||

| R0 | 1.000 | - | 0.0101 | 1.000 | 0.0331 | |

| R1 | 1.773 | 1.149-2.736 | 1.632 | 1.041-2.529 | ||

| Bile duct invasion | ||||||

| Negative | 1.000 | - | 0.654 | |||

| Positive | 1.100 | 0.724-1.677 | ||||

| Duodenal invasion | ||||||

| Negative | 1.000 | - | 0.415 | |||

| Positive | 1.188 | 0.785-1.796 | ||||

| Nerve plexus invasion | ||||||

| Negative | 1.000 | - | 0.484 | |||

| Positive | 1.159 | 0.766-1.754 | ||||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||

| Negative | 1.000 | - | 0.238 | |||

| Positive | 1.285 | 0.847-1.947 | ||||

| Venous invasion | ||||||

| Negative | 1.000 | - | 0.0021 | 1.000 | 0.0101 | |

| Positive | 2.771 | 1.447-5.304 | 2.395 | 1.237-4.636 | ||

| Postop. chemotherapy | 0.427 | |||||

| No | 1.000 | - | ||||

| Yes | 0.846 | 0.561-1.277 | ||||

| Postop. radiotherapy | 0.944 | |||||

| No | 1.000 | - | ||||

| Yes | 1.018 | 0.624-1.660 | ||||

| Op. blood loss (100 mL) | 1.001. | 1.000-1.002 | 0.081 | |||

| Postop. hospital stay | 1.026 | 0.999-1.054 | 0.057 | |||

Advances in surgical techniques, a better understanding of anatomy and improvements in technology have considerably increased the safety and R0 resection rates for PD[16-18]. However, in the past decades long-term OS after resectional surgery with curative intent has not significantly improved. This led to the focus on factors influencing long-term survival, and resection margin status is one of the important factors.

At present, there is still no universally accepted and standardized technique to section a resected specimen obtained after PD for histological studies under the microscope. The accepted standard for evaluation of resection margins includes the TNM, Japan Pancreas Society and British Royal College of Pathologists standards[6-8]. Even the definition of R1 resection differs[6,8]. Based on different standards for resection margin, postoperative long-term survival in patients with pancreatic head cancer varies (Table 4). While some studies suggested that patients with R0 resection have better postoperative OS than R1 resection, other studies concluded that there were no differences in OS between R0 and R1 resection[19-23].

| Ref. | R1/R2 patients, n (%) | Resection status | Median R1/R2 survival in mo | Median R0 survival in mo |

| Podda et al[19], 2017 | 34 (36) | R1 | 18 | 26 |

| Sugiura et al[20], 2013 | 40 (19) | R1 | 23 | 30 |

| Petermann et al[13], 2013 | 36 (38) | R1 | 14 | 19 |

| Zhang et al[14], 2012 | 48 (57) | R1 | 17 | 29 |

| Rau et al[21], 2012 | 56 (44) | R1 | 14 | 19 |

| Fatima et al[22], 2010 | 149 (24) | R1/R2 | 15/10 | 19 |

| Kato et al[4], 2009 | 61 (35) | R1/R2 | 9/6 | 15 |

| Raut et al[5], 2007 | 60 (17) | R1 | 22 | 28 |

| Present study | 38 (31) | R1 | 16 | 23 |

This study investigated the impact of resection margin status on postoperative long-term OS in patients using the TNM standard. The results suggested that patients with R0 resection had significantly better postoperative long-term OS than that of patients with R1 resection. The other independent factor influencing long-term OS was venous invasion. Other standard clinical parameters, such as age, sex, tumor size, differentiation degree, bile duct invasion, duodenal invasion, nerve plexus invasion, lymph node metastasis and intraoperative blood loss, were not found to be associated with postoperative long-term OS in our study.

The professional knowledge and experience of pathologists have a significant influence on determining the resection margin status. It is difficult for a pathologist on his own to orientate a resected specimen after PD and to decide where to section the sample to microscopically study resection margin status, which is an important factor for distinguishing R0 from R1 resection in pancreatic head cancer[24]. At our hospital, after the surgical specimens are fixed in formalin, the operating surgeon and a pathologist would orientate the sample together. The pathologist then obtains, stains and examines tissue slices at the appropriate sites to look at the resection margin status. The resection margins of the resected specimen routinely include the gastric, duodenal, choledochal and pancreatic cut ends; margins of the pancreatic groove for the portal/superior mesenteric vein and artery; the connective tissue layers surrounding the pancreas; and in appropriate cases, the cut ends of resected ends of the portal/superior mesenteric vein. Such samples obtained together by the pathologists and the operating surgeons provided an accurate method to define the significant resection margins.

The connective tissues on the posterior side of the pancreatic head and around the portal/superior mesenteric vein, superior mesenteric artery, celiac axis and abdominal aorta are the common sites of residual tumor cells left after PD and present as R1 resection margins on microscopic examination[10,25-27]. To achieve higher R0 resection rates, complete resection of the mesopancreas[28,29], clearance of the mesopancreas triangle[30] and even resection of the mesopancreatoduodenum[31] have been proposed.

We must note that this study had limitations. First, our sample size was small, and patients who died of complications in the perioperative period were not included because this study focused only on long-term OS. Second, the follow-up isolation time was too long, which would affect the accuracy of overall survival. Future studies will be required to determine the impact of resection margin status on the long-term overall survival of patients with pancreatic head carcinoma after PD in a larger sample population.

This study suggested that patients with R0 resection had significantly better postoperative long-term OS than that of patients with R1 resection. Venous invasion was an independent factor influencing survival. Adequate resection to achieve R0 resection can improve postoperative long-term OS for patients with pancreatic head cancer.

In recent years, the status of resection margin of patients with pancreatic head carcinoma after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) has received much attention, but controversies still exist.

This study aimed to examine the impact of resection margin status on long-term overall survival (OS) of patients with pancreatic head carcinoma after PD.

This study examined the impact of resection margin status on long-term OS of patients with pancreatic head carcinoma after PD by the tumor node metastasis standard.

Consecutive patients with pancreatic head carcinoma who underwent PD at the Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital between May 2010 and May 2016 were included. The impact of resection margin status on long-term OS was retrospectively analyzed.

Among the 124 patients, R0 resection was achieved in 85 patients (68.5%), R1 resection in 38 patients (30.7%) and R2 resection in 1 patient (0.8%). The 1- and 3-year OS rates were significantly higher for the patients who underwent R0 resection than those who underwent R1 resection (1-year OS rates: 69.4% vs 53.0%; 3-year OS rates: 26.9% vs 11.7%). Multivariate analysis showed resection margin status and venous invasion to be significant risk factors of OS. Future studies should be required to determine the impact of resection margin status on long-term OS of patients with pancreatic head carcinoma after PD in a larger sample population.

This study suggested that patients with R0 resection had significantly better postoperative long-term OS than those with R1 resection. Venous invasion was an independent factor influencing survival. Adequate resection to achieve R0 resection can improve postoperative long-term OS for patients with pancreatic head cancer.

The sample size of this study was small and patients who died of complications in the perioperative period were not included because this study focused only on long-term OS. The follow-up isolation time was also too long in this study, which would affect the accuracy of OS. Future studies will be required to determine the impact of resection margin status on long-term OS of patients with pancreatic head carcinoma after PD in larger sample population.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Roman ID, Tinsley A S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Ethun CG, Kooby DA. The importance of surgical margins in pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2016;113:283-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12135] [Cited by in RCA: 12991] [Article Influence: 1443.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Kooby DA, Lad NL, Squires MH, Maithel SK, Sarmiento JM, Staley CA, Adsay NV, El-Rayes BF, Weber SM, Winslow ER, Cho CS, Zavala KA, Bentrem DJ, Knab M, Ahmad SA, Abbott DE, Sutton JM, Kim HJ, Yeh JJ, Aufforth R, Scoggins CR, Martin RC, Parikh AA, Robinson J, Hashim YM, Fields RC, Hawkins WG, Merchant NB. Value of intraoperative neck margin analysis during Whipple for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a multicenter analysis of 1399 patients. Ann Surg. 2014;260:494-501; discussion 501-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kato K, Yamada S, Sugimoto H, Kanazumi N, Nomoto S, Takeda S, Kodera Y, Morita S, Nakao A. Prognostic factors for survival after extended pancreatectomy for pancreatic head cancer: influence of resection margin status on survival. Pancreas. 2009;38:605-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Raut CP, Tseng JF, Sun CC, Wang H, Wolff RA, Crane CH, Hwang R, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK, Lee JE, Pisters PW, Evans DB. Impact of resection status on pattern of failure and survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;246:52-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind CH. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell Press, 2010. . |

| 7. | Japan Pancreas Society. General rules for the study of pancreatic cancer. 6th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara, 2009. . |

| 8. | Campbell F, Foulis AK, Verbeke CS. Dataset for the histopathological reporting of carcinomas of the pancreas, ampulla of Vater and common bile duct. London: Royal College of Pathologists, 2010. . |

| 9. | Chang DK, Johns AL, Merrett ND, Gill AJ, Colvin EK, Scarlett CJ, Nguyen NQ, Leong RW, Cosman PH, Kelly MI, Sutherland RL, Henshall SM, Kench JG, Biankin AV. Margin clearance and outcome in resected pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2855-2862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Esposito I, Kleeff J, Bergmann F, Reiser C, Herpel E, Friess H, Schirmacher P, Büchler MW. Most pancreatic cancer resections are R1 resections. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1651-1660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 562] [Article Influence: 33.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lad NL, Squires MH, Maithel SK, Fisher SB, Mehta VV, Cardona K, Russell MC, Staley CA, Adsay NV, Kooby DA. Is it time to stop checking frozen section neck margins during pancreaticoduodenectomy? Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3626-3633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Verbeke CS, Leitch D, Menon KV, McMahon MJ, Guillou PJ, Anthoney A. Redefining the R1 resection in pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1232-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Petermann D, Demartines N, Schäfer M. Severe postoperative complications adversely affect long-term survival after R1 resection for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2013;37:1901-1908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhang Y, Frampton AE, Cohen P, Kyriakides C, Bong JJ, Habib NA, Spalding DR, Ahmad R, Jiao LR. Tumor infiltration in the medial resection margin predicts survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1875-1882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Agha RA, Borrelli MR, Vella-Baldacchino M, Thavayogan R, Orgill DP; STROCSS Group. The STROCSS statement: Strengthening the Reporting of Cohort Studies in Surgery. Int J Surg. 2017;46:198-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 688] [Cited by in RCA: 713] [Article Influence: 89.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Okada K, Kawai M, Hirono S, Miyazawa M, Shimizu A, Kitahata Y, Tani M, Yamaue H. A replaced right hepatic artery adjacent to pancreatic carcinoma should be divided to obtain R0 resection in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2015;400:57-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Inoue Y, Saiura A, Yoshioka R, Ono Y, Takahashi M, Arita J, Takahashi Y, Koga R. Pancreatoduodenectomy With Systematic Mesopancreas Dissection Using a Supracolic Anterior Artery-first Approach. Ann Surg. 2015;262:1092-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Aimoto T, Mizutani S, Kawano Y, Matsushita A, Yamashita N, Suzuki H, Uchida E. Left posterior approach pancreaticoduodenectomy with total mesopancreas excision and circumferential lymphadenectomy around the superior mesenteric artery for pancreatic head carcinoma. J Nippon Med Sch. 2013;80:438-445. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Podda M, Thompson J, Kulli CTG, Tait IS. Vascular resection in pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary cancers. A 10 year retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2017;39:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sugiura T, Uesaka K, Mihara K, Sasaki K, Kanemoto H, Mizuno T, Okamura Y. Margin status, recurrence pattern, and prognosis after resection of pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2013;154:1078-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rau BM, Moritz K, Schuschan S, Alsfasser G, Prall F, Klar E. R1 resection in pancreatic cancer has significant impact on long-term outcome in standardized pathology modified for routine use. Surgery. 2012;152:S103-S111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fatima J, Schnelldorfer T, Barton J, Wood CM, Wiste HJ, Smyrk TC, Zhang L, Sarr MG, Nagorney DM, Farnell MB. Pancreatoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma: implications of positive margin on survival. Arch Surg. 2010;145:167-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nitta T, Nakamura T, Mitsuhashi T, Asano T, Okamura K, Tsuchikawa T, Tamoto E, Murakami S, Noji T, Kurashima Y, Ebihara Y, Nakanishi Y, Shichinohe T, Hirano S. The impact of margin status determined by the one-millimeter rule on tumor recurrence and survival following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Surg Today. 2017;47:490-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Komatsu H, Egawa S, Motoi F, Morikawa T, Sakata N, Naitoh T, Katayose Y, Ishida K, Unno M. Clinicopathological features and surgical outcomes of adenosquamous carcinoma of the pancreas: a retrospective analysis of patients with resectable stage tumors. Surg Today. 2015;45:297-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Janot MS, Kersting S, Belyaev O, Matuschek A, Chromik AM, Suelberg D, Uhl W, Tannapfel A, Bergmann U. Can the new RCP R0/R1 classification predict the clinical outcome in ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:917-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Popescu I, Dumitrascu T. Total meso-pancreas excision: key point of resection in pancreatic head adenocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:202-207. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Nagakawa Y, Hosokawa Y, Osakabe H, Sahara Y, Takishita C, Nakajima T, Hijikata Y, Kasahara K, Kazuhiko K, Saito K, Tsuchida A. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with right-oblique posterior dissection of superior mesenteric nerve plexus is logical procedure for pancreatic cancer with extrapancreatic nerve plexus invasion. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:2371-2376. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Gaedcke J, Gunawan B, Grade M, Szöke R, Liersch T, Becker H, Ghadimi BM. The mesopancreas is the primary site for R1 resection in pancreatic head cancer: relevance for clinical trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395:451-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Agrawal MK, Thakur DS, Somashekar U, Chandrakar SK, Sharma D. Mesopancreas: myth or reality? JOP. 2010;11:230-233. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Bouassida M, Mighri MM, Chtourou MF, Sassi S, Touinsi H, Hajji H, Sassi S. Retroportal lamina or mesopancreas? Lessons learned by anatomical and histological study of thirty three cadaveric dissections. Int J Surg. 2013;11:834-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kawabata Y, Tanaka T, Nishi T, Monma H, Yano S, Tajima Y. Appraisal of a total meso-pancreatoduodenum excision with pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic head carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:574-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |