Published online Dec 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i23.4150

Peer-review started: August 8, 2019

First decision: September 23, 2019

Revised: October 24, 2019

Accepted: November 14, 2019

Article in press: November 14, 2019

Published online: December 6, 2019

Processing time: 119 Days and 18.6 Hours

Odontogenic infection is one of the common infectious diseases in oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions. Clinically, if early odontogenic infections such as acute periapical periodontitis, alveolar abscess, and pericoronitis of wisdom teeth are not treated timely, effectively and correctly, the infected tissue may spread up to the skull and brain, down to the thoracic cavity, abdominal cavity and other areas through the natural potential fascial space in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck. Severe multi-space infections are formed and can eventually lead to life-threatening complications (LTCs), such as intracranial infection, pleural effusion, empyema, sepsis and even death.

We report a rare case of death in a 41-year-old man with severe odontogenic multi-space infections in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions. One week before admission, due to pain in the right lower posterior teeth, the patient placed a cigarette butt dipped in the pesticide "Miehailin" into the "dental cavity" to relieve the pain. Within a week, the infection gradually spread bilaterally to the floor of the mouth, submandibular space, neck, chest, waist, back, temporal and other areas. The patient had difficulty breathing, swallowing and eating, and was transferred to our hospital as an emergency admission. Following admission, oral and maxillofacial surgeons immediately organized consultations with doctors in otolaryngology, thoracic surgery, general surgery, hematology, anesthesia and the intensive care unit to assist with treatment. The patient was treated with the highest level of antibiotics (vancomycin) and extensive abscess incision and drainage in the oral, maxillofacial, head and neck, chest and back regions. Unfortunately, the patient died of septic shock and multiple organ failure on the third day after admission.

Odontogenic infection can cause serious multi-space infections in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions, which can result in multiple LTCs. The management and treatment of LTCs such as multi-space infections should be multidisciplinary led by oral and maxillofacial surgeons.

Core tip: As reported in this article, despite current medical advances, when a patient has fatal life-threatening complications, the risk of death is high. Prevention of early odontogenic diseases is more meaningful than the treatment of late odontogenic multi-space infections. Furthermore, it is also very important to raise awareness of oral health care in remote mountainous areas of China.

- Citation: Dai TG, Ran HB, Qiu YX, Xu B, Cheng JQ, Liu YK. Fatal complications in a patient with severe multi-space infections in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(23): 4150-4156

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i23/4150.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i23.4150

Odontogenic infections such as acute periapical periodontitis, alveolar abscess, and pericoronitis of wisdom teeth are common infectious diseases in the oral and maxillofacial regions. Clinically, if these diseases are not treated timely, effectively and correctly in the early stage, the infected tissue may spread up to the skull and brain, down to the thoracic cavity, abdominal cavity and back through the natural potential fascial space in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions[1]. Severe multi-space infections are formed, which can eventually lead to life-threatening complications (LTCs) such as intracranial infection, pleural effusion, empyema, sepsis and even death[2]. When a patient develops LTCs, treatment becomes very complicated, the outcome is poor and the mortality rate is high[3]. Nowadays, the occurrence of serious LTCs is less frequent due to rational use of antibiotics and early treatment of odontogenic diseases. Nevertheless, it is still difficult to predict the development of severe odontogenic multi-space infections in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions. We report a patient with odontogenic infection who was not effectively treated in the initial stage, and consequently developed severe multi-space infections in the oral, maxillofacial, head and neck, chest and back, mediastinum and posterior abdominal wall regions, and subsequently died of septic shock and acute multiple organ failure.

A 41-year-old man presented with pain in the right lower posterior teeth, followed by swelling and pain in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions for 7 d, and difficulty in breathing and swallowing for 2 d.

One week before admission, due to pain in the right lower posterior teeth, the patient placed a cigarette butt dipped in the pesticide "Miehailin" into the "dental cavity" to relieve the pain. However, two days later, there was no significant improvement in dental pain and he visited a local community clinic where the doctors removed the cigarette butt and the patient received an infusion of anti-inflammatory drugs for 4 d. However, the odontogenic infections gradually became aggravated, and spread bilaterally to the floor of the mouth, submandibular space, neck, chest, waist, back, temporal and other areas. The patient also began to have difficulty in breathing, swallowing and eating. Due to these complications, the patient was transferred to our hospital for follow-up treatment as an emergency admission. Since the onset of illness, he had been mentally exhausted, with a poor diet, poor sleep, and weight loss of approximately 2.5 kg.

Healthy, with no specific diseases.

None.

Physical examination showed that the patient had an acutely painful face, extensive swelling and pneumatosis in the bilateral temporal, oral, maxillofacial, neck, chest, waist and back regions, combined with skin redness and high temperature. The submandibular space and neck regions pulsated when touched. Puncture revealed purulent fluid which was black, thin, with bubbles and had a foul odor. When the patient was admitted to hospital, mouth opening was less than 1 cm; therefore, the tooth lesion could not be examined properly.

Laboratory examination results on emergency admission were as follows: leukocyte count was 13.53 × 109/L, neutrophil ratio was 88.40%, hypersensitive C-reactive protein was > 180 mg/L, and procalcitonin was 9.8 ng/mL. Electrolyte results were: potassium was 5.65 mmol/L, sodium was 136.4 mmol/L, chlorine was 101.9 mmol/L, calcium was 1.91 mmol/L, and magnesium was 0.93 mmol/L. Liver and kidney function test results were as follows: alanine aminotransferase was 19 U/L, glutamic oxaloacetic aminotransferase was 23 U/L, creatinine was 94 µmol/L, and urea was 19.1 mmol/L. The platelet count was 41.0 × 109/L and the D-dimer level was 1184 ng/mL. The results of blood culture indicated infection with Streptococcus viridans. Drug sensitivity testing indicated that the organism was sensitive to penicillin antibiotics.

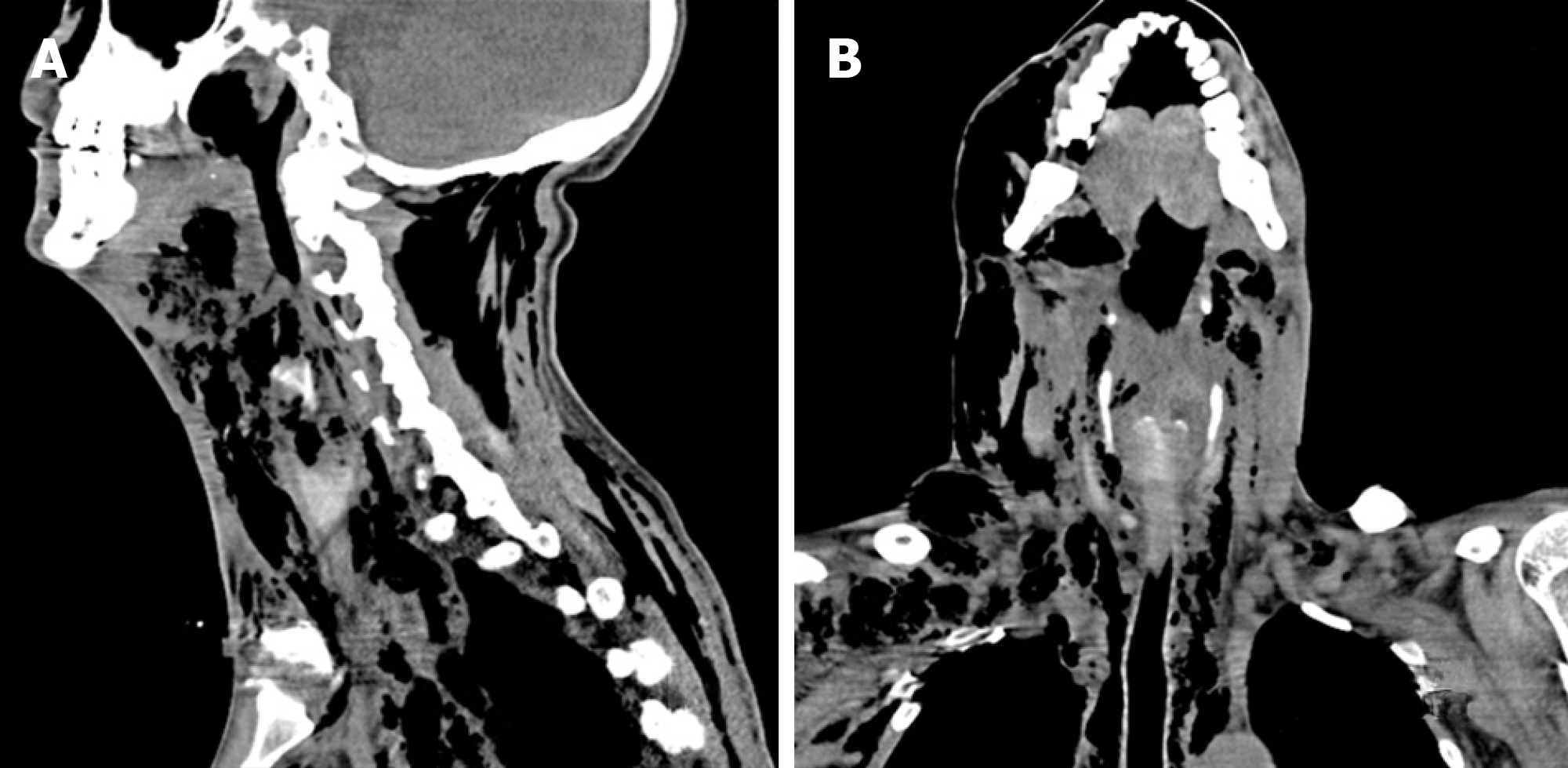

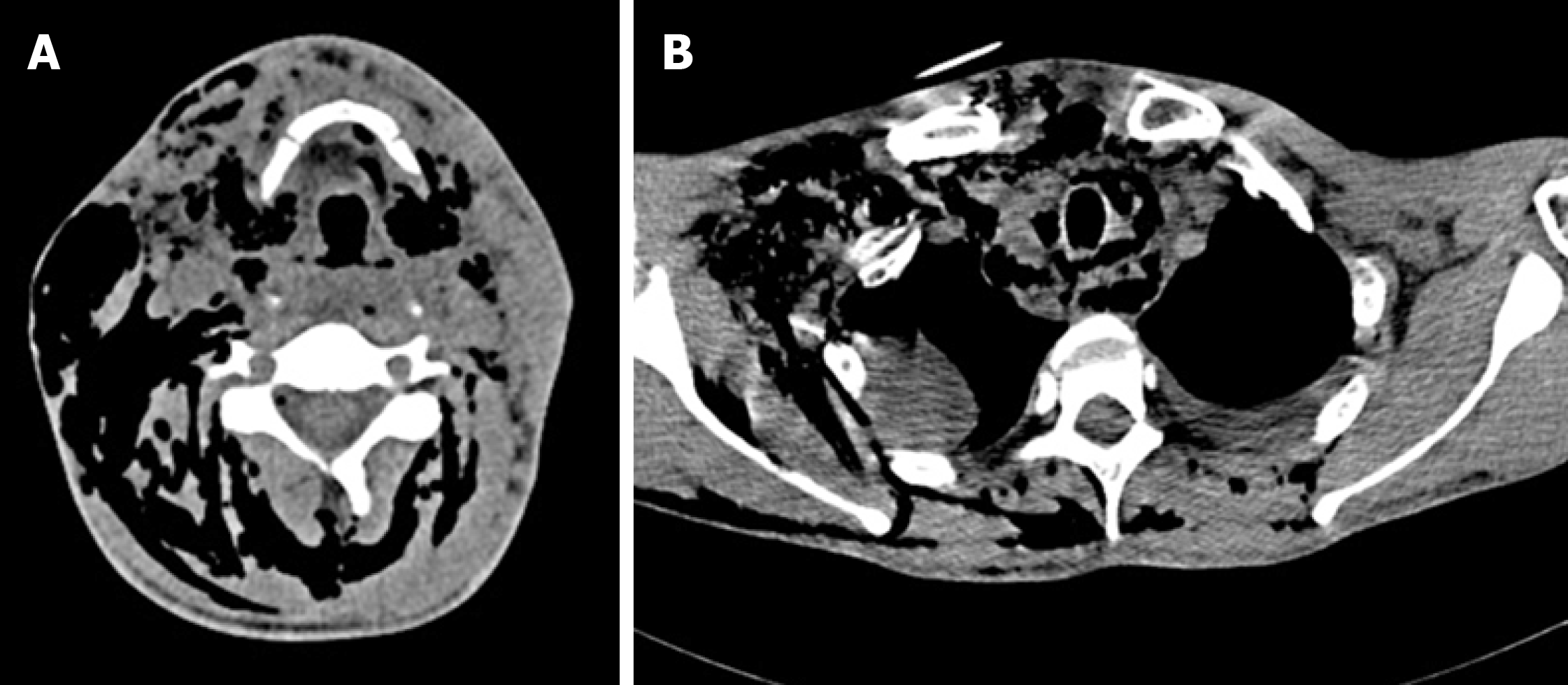

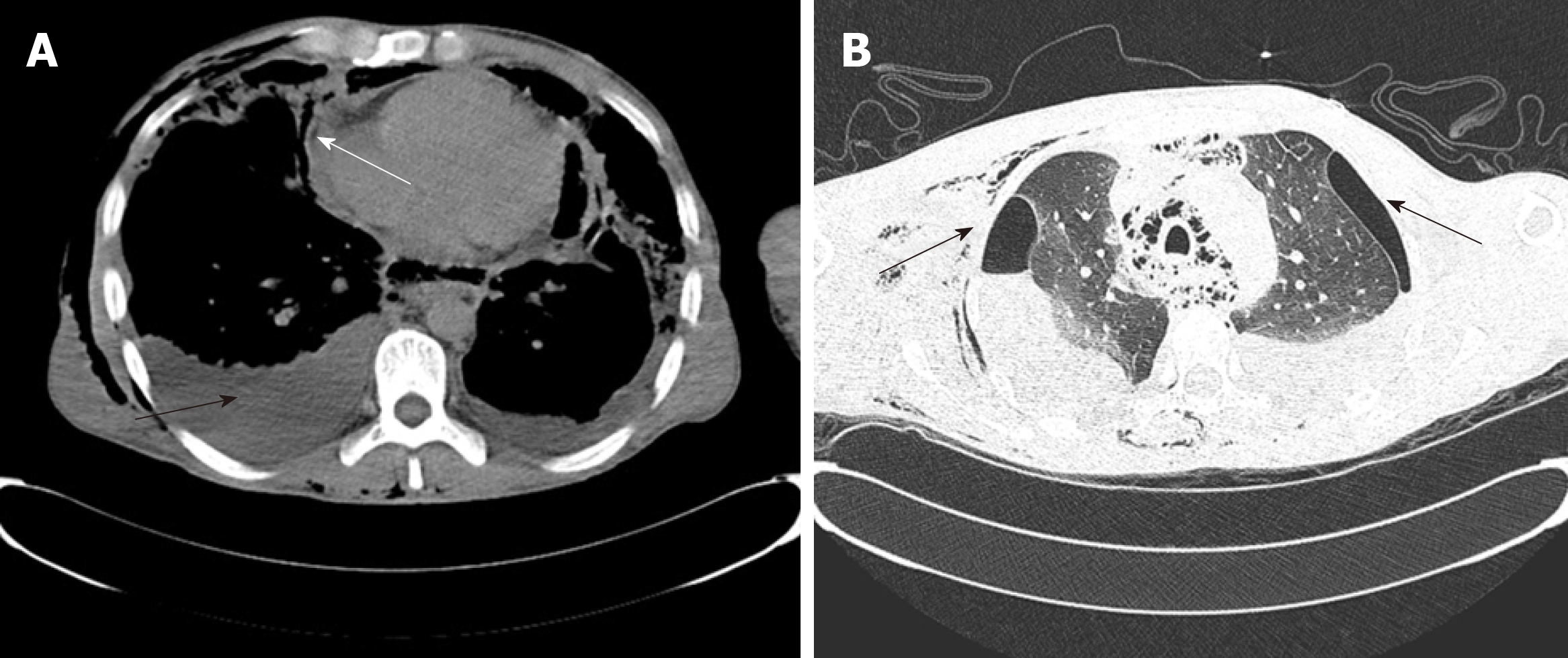

Computed tomography scans of the maxillofacial, neck and chest regions showed extensive swelling and pneumatosis in soft tissues bilaterally in the oral, maxillofacial, temporal, cervical, parapharyngeal space, chest, back, mediastinum and posterior abdominal wall regions (Figures 1 and 2). The upper respiratory tract was narrowed slightly and bilateral lung pneumothorax was observed. A small amount of effusion was seen bilaterally in the pleura and pericardium (Figure 3A). Lung pneumothorax was more serious on the left side and the compression ratio was approximately 20%-30% (Figure 3B). Pulmonary infection was seen in both lungs, particularly in the left lung.

Initial diagnosis on admission was severe multi-space infections bilaterally in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions; secondary infections in the thorax, back and waist; mediastinal abscess; bilateral pneumothorax; bilateral pulmonary infection; purulent pleural effusion; pericardial effusion; secondary thrombocytopenia.

Immediately after admission, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for specialized intensive care.

Oral and maxillofacial surgeons immediately organized consultations and discussion of treatment plans with doctors from otolaryngology, thoracic surgery, general surgery, hematology, anesthesiology and ICU.

Oral and maxillofacial surgeons were responsible for extensive abscess incision and drainage in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions under emergency general anesthesia. Thoracic surgeons were responsible for thoracic and pericardial puncture, catheter drainage and pneumothorax management. General surgeons were responsible for the management of back and waist infections. Otolaryngologists and anesthesiologists were responsible for anesthesia and respiratory management. The hematologist was responsible for platelets and blood transfusion. ICU doctors were responsible for intensive care, antimicrobial administration (Norvancomycin hydrochloride), nutritional support, water, electrolytes and acid-base stability. On the first day after surgery, platelets decreased to 22.00 × 109/L, and liver and kidney function tests were abnormal (alanine aminotransferase 186 U/L, glutamic oxalate aminotransferase 450 U/L, cholinesterase 968 U/L, urea 21.3 mmol/L, creatinine 153 µmol/L). Electrolytes were also abnormal (potassium 4.77 mmol/L, sodium 148.8 mmol/L, chlorine 114.6 mmol/L, calcium 1.38 mmol/L). On the second day after surgery, liver and kidney function continued to deteriorate (alanine aminotransferase increased to 168 U/L, glutamic oxalate aminotransferase increased to 1025 U/L, cholinesterase increased to 814 U/L, urea increased to 34.44 mmol/L, creatinine increased to 259 µmol/L). On the third day after surgery, the patient developed septic shock and sudden respiratory and cardiac arrest, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation was implemented immediately. Unfortunately, the rescue efforts were ineffective and the patient died.

Despite unremitting efforts by the doctors, the patient eventually died of septic shock and acute hepatic and renal insufficiency. Medical diagnoses at death were as follows: Septic shock; acute hepatic and renal insufficiency; severe multi-space infections bilaterally in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions; secondary infections of the thorax, back and waist; mediastinal abscess; bilateral pneumothorax; bilateral pulmonary infection; purulent pleural effusion; pericardial effusion; secondary thrombocytopenia.

Approximately 62.6% of oral and maxillofacial head and neck space infections are odontogenic and multiple spaces are involved in 22.5% of cases. The age of these patients ranged from 2 to 84 years and the mortality rate was 1%[4]. Huang et al[5] reported that the incidence of LTCs such as multi-space infections in the head and neck regions was about 12.20%, and descending mediastinitis was the most frequent (56.06%), followed by airway obstruction, pneumonia, pericarditis, intraorbital infection, multiple organ failure, intracranial infection and sudden cardiac death. Twelve patients (18.2%) with multi-space infections died during treatment.

In many remote rural areas of China, there is a proverb that toothache is not a disease. Due to this silly proverb, many people do not have a strong sense of oral health care, think that dental pain is not a disease, do not regularly see a dentist , or even use their own "indigenous method" to relieve pain. As reported in this case, the patient put a cigarette butt dipped in the pesticide "Miehailin" into the "dental cavity" to relieve the pain. Miehailin is a highly effective insecticide, which has a good quick-killing effect on mosquitoes, flies, cockroaches, bedbugs, ants and other pests. Why did our patient rapidly progress from having a simple odontogenic disease to multi-space infections in the oral, maxillofacial, head and neck regions, which quickly spread to the temporal, chest, mediastinum, back and waist regions? Firstly, we think that the toxicity of pesticides may play a role in the rapid development of diseases. Secondary thrombocytopenia in this patient is the best proof of this proposal. Secondly, in the early stage, the patient visited a non-dental medical institution. The clinician only removed the cigarette butt without any other treatment for the tooth lesion, which resulted in spread of the odontogenic infection. Thirdly, when the patient's odontogenic infection was confined to the oral and maxillofacial region, timely incision and drainage were not performed, which was an important factor in the rapid spread of infection throughout his body. When the patient was rushed to our hospital, oral and maxillofacial surgeons took the lead, and doctors from various departments were urgently consulted to assist in his treatment and formulate a reasonable and appropriate rescue plan. All available rescue measures were adopted, including timely intensive care, anesthesia intubation to ensure that the respiratory tract was unobstructed, extensive systemic abscess incision and drainage under general anesthesia, accurate thoracic and pericardial puncture abscess drainage, administration of the highest level of antibiotics, and platelet transfusion. Unfortunately, the patient died despite unremitting efforts by the doctors. In an analysis of the causes of death, we believe that there were many causes, but the main causes were septic shock, acute multiple organ failure, secondary thrombocytopenia, and pesticide poisoning.

Odontogenic infection can be treated effectively, but can also lead to severe multi-space infections in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions. The traditional treatment of multi-space infections in these regions is correct anti-bacterial drug administration and abscess incision and drainage[6]. In recent years, Qiu et al[7] and Li et al[8] reported that a vacuum sealing drainage-assisted irrigation technique used in the treatment of severe multi-space infections in the oral and maxillofacial cervical regions showed high clinical and therapeutic efficacy. As the infection in our patient was very serious, following discussion and approval by the Drug Administration Committee, we administered the highest level of antibiotics (Norvancomycin hydrochloride) to combat the infection. For extensive incision and drainage of the multi-space infections in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions, we adopted disposable multi-functional tube drainage and irrigation technology. This technique can not only irrigate antibacterial drugs into the pus cavity continuously, but also remove infectious wastes by negative pressure suction.

Multi-space infections in the oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions can cause several LTCs. Effective prevention of the occurrence of LTCs is a challenge that oral and maxillofacial surgeons must address. Huang et al[5] reported that older age and underlying systemic disease can increase the risk of multi-space infections. Gallo et al[9] reported that algorithm-based management of head and neck space infections was successful in avoiding the onset LTCs. To identify the deep neck infection factors related to LTCs, Mejzlik et al[10] conducted a multi-institutional study involving 586 patients. The results showed that patients with neck movement disturbances, dysphonia, dyspnea and swelling of the external neck, accompanied by severe pain, and inflammatory changes in the retropharyngeal space and large vessel areas, with culture-confirmed infection with Candida albicans, are likely to develop LTCs. Osunde et al[11] reported that early recognition and treatment of established cases are necessary to prevent considerable morbidity and mortality. Heim et al[12] showed that simultaneous removal of the infection focus (tooth) and abscess incision reduced the length of hospital stay. Combining literature results and our clinical practice, we believe that patients with serious systemic diseases, extensive infection, extremely abnormal blood and biochemical indicators, and severe respiratory obstruction can be used as predictors of mortality in multi-space infections.

Odontogenic infection can cause serious multi-space infections in oral and maxillofacial head and neck regions, which can cause several LTCs. As shown in the case reported herein, despite current medical advances, when a patient develops LTCs, the risk of death is high. The prevention of early odontogenic diseases is more meaningful than the treatment of late odontogenic multi-space infections. It is very important to treat the various stages of dental diseases, such as pulp diseases, periapical diseases, and periodontal diseases, effectively and promptly. Furthermore, it is also important to raise awareness of oral health care in remote mountainous areas of China.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abd-Elsalam S, Monti M S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Webster JR E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Maroldi R, Farina D, Ravanelli M, Lombardi D, Nicolai P. Emergency imaging assessment of deep neck space infections. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2012;33:432-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wills PI, Vernon RP. Complications of space infections of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1981;91:1129-1136. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Larawin V, Naipao J, Dubey SP. Head and neck space infections. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:889-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pourdanesh F, Dehghani N, Azarsina M, Malekhosein Z. Pattern of odontogenic infections at a tertiary hospital in tehran, iran: a 10-year retrospective study of 310 patients. J Dent (Tehran). 2013;10:319-328. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Huang L, Jiang B, Cai X, Zhang W, Qian W, Li Y, Guan X, Liang X, Zhou L, Zhu J, Zhang Z. Multi-Space Infections in the Head and Neck: Do Underlying Systemic Diseases Have a Predictive Role in Life-Threatening Complications? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:1320.e1-1320.10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bratton TA, Jackson DC, Nkungula-Howlett T, Williams CW, Bennett CR. Management of complex multi-space odontogenic infections. J Tenn Dent Assoc. 2002;82:39-47. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Qiu Y, Li Y, Gao B, Li J, Pan L, Ye Z, Lin Y, Lin L. Therapeutic efficacy of vacuum sealing drainage-assisted irrigation in patients with severe multiple-space infections in the oral, maxillofacial, and cervical regions. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2019;47:837-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li CM, Xie CL, Hu S, Sun Q, Li GH, Niu ZX, Sun ML. [Clinical value of vacuum sealing drainage in the treatment of oral and maxillofacial space infection]. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2019;37:62-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gallo O, Mannelli G, Lazio MS, Santoro R. How to avoid life-threatening complications following head and neck space infections: an algorithm-based approach to apply during times of emergency. When and why to hospitalise a neck infection patient. J Laryngol Otol. 2018;132:53-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mejzlik J, Celakovsky P, Tucek L, Kotulek M, Vrbacky A, Matousek P, Stanikova L, Hoskova T, Pazs A, Mittu P, Chrobok V. Univariate and multivariate models for the prediction of life-threatening complications in 586 cases of deep neck space infections: retrospective multi-institutional study. J Laryngol Otol. 2017;131:779-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Osunde OD, Akhiwu BI, Efunkoya AA, Adebola AR, Iyogun CA, Arotiba JT. Management of fascial space infections in a Nigerian teaching hospital: A 4-year review. Niger Med J. 2012;53:12-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Heim N, Warwas FB, Wiedemeyer V, Wilms CT, Reich RH, Martini M. The role of immediate versus secondary removal of the odontogenic focus in treatment of deep head and neck space infections. A retrospective analysis of 248 patients. Clin Oral Investig. 2019;23:2921-2927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |