Published online Dec 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i23.4111

Peer-review started: September 27, 2019

First decision: October 24, 2019

Revised: November 16, 2019

Accepted: November 20, 2019

Article in press: November 20, 2019

Published online: December 6, 2019

Processing time: 70 Days and 0.6 Hours

Hepatocellular adenoma (HCA) is very rare and has a high misdiagnosis rate through clinical and imaging examinations. We report a case of giant HCA of the left liver in a young woman that was diagnosed by medical imaging and pathology.

A 21-year-old woman was admitted to our department for a giant hepatic tumor measuring 22 cm × 20 cm × 10 cm that completely replaced the left hepatic lobe. Her laboratory data only suggested mildly elevated liver function parameters and C-reactive protein levels. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed mixed density in the tumor. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the tumor revealed a heterogeneous hypointensity on T1-weighed MR images and heterogeneous hyperintensity on T2-weighed MR images. On dynamic contrast CT and MRI scans, the tumor presented marked enhancement and the subcapsular feeding arteries were clearly visible in the arterial phase, with persistent enhancement in the portal and delayed phases. Moreover, the tumor capsule was especially prominent on T1-weighted MR images and showed marked enhancement in the delayed phase. Based on these imaging manifestations, the tumor was initially considered to be an HCA. Subsequently, the tumor was completely resected and pathologically diagnosed as an HCA.

HCA is an extremely rare hepatic tumor. Preoperative misdiagnoses were common not only due to the absence of special clinical manifestations and laboratory examination findings, but also due to the clinicians’ lack of practical diagnostic experience and vigilance in identifying HCA on medical images. Our case highlights the importance of the combination of contrast-enhanced CT and MRI in the preoperative diagnosis of HCA.

Core tip: Hepatocellular adenoma (HCA) is not easily identifiable due to its rarity and atypical presentations. Herein, we provide a successful example of a preoperative diagnosis of a giant HCA in a young woman that was found by physical examination. Our case emphasizes that the visualization of the subcapsular feeding arteries in the arterial phase, the conspicuous capsule on T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images, and the markedly enhanced capsule on the delayed-phase MR images can be the important characteristics for the preoperative diagnosis of HCA.

- Citation: Zheng LP, Hu CD, Wang J, Chen XJ, Shen YY. Radiological aspects of giant hepatocellular adenoma of the left liver: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(23): 4111-4118

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i23/4111.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i23.4111

Hepatocellular adenoma (HCA), also known as hepatic adenoma, is a rare benign tumor of the liver, which can be divided into two categories: Congenital and acquired. Congenital HCA is more common in infants and may stem from the unconnected isolated embryonic hepatocytes. Acquired HCA occurs mostly in young women with a history of oral contraceptive use, with an estimated incidence of 3-4 per 100000 women[1,2]. This may be due to the fact that oral contraceptives promote necrosis of hepatocytes and regeneration of nodules, leading to the development of HCA. However, other predisposing factors, such as androgen treatment, diabetes mellitus, and glycogen storage disease, have been gradually recognized[3-5].

In the early stage of the disease, HCA rarely causes clinical symptoms or has laboratory indicators of abnormal function, most of which are found in physical examinations. The diagnoses of HCA mainly depend on imaging examinations, but in fact, the misdiagnosis rate of the disease by imaging is very high. Liver biopsy is helpful for definite preoperative diagnosis and reduction of misdiagnosis, but there is still some controversy because of its risk of intertumoral and intraperitoneal bleeding and iatrogenic spread of malignancies.

HCA is a group of heterogeneous tumors. According to the characteristics of genotype or immunophenotype, HCA can be classified into four different molecular subtypes, namely, hepatocyte nuclear factor-1α-inactivated HCA (subtype H-HCA), beta-catenin-activated HCA (subtype b-HCA), inflammatory HCA (subtype I-HCA), and unclassified HCA. Approximately 10% of subtype I-HCA cases coexist with a subtype b-HCA[6,7]. The most important complications of HCA are spontaneous hemorrhage and malignant transformation to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[8,9]. The risk factors for HCC from HCA include large tumor size (>5 cm) and β-catenin-activated subtype[10]. Therefore, HCA must be identified and treated promptly.

In our case, the giant hepatic tumor of the patient was found by physical examination without etiology. After computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, an initial diagnosis of HCA was made. Resection of the tumor was performed, and the tumor was pathologically diagnosed as HCA. Our case emphasizes that visualization of the tumor-feeding arteries in the arterial phase, the conspicuous capsule on T1-weighted MR images, and the markedly enhanced capsule on the delayed-phase MR images can be the important characteristics for the preoperative diagnosis of HCA.

A 21-year-old woman was admitted to our department for a giant hepatic tumor that was found one month prior during a physical examination.

One month ago, an ultrasound examination at a local hospital revealed a giant hepatic tumor. However, the patient did not experience any obvious abdominal pain, distention, nausea, vomiting, chills, or fever.

She denied a medical history of oral contraceptive use, hepatitis, metabolic disorders, and immunodeficiency diseases.

The patient was unmarried, and her last menstrual period ended 11 d before admission. No additional family history was presented.

The patient’s sclera was not stained yellow and superficial lymph nodes were not enlarged. Her abdominal examination showed that her abdomen was flat and soft, and there was no obvious tenderness throughout her abdomen. The lower margin of the liver was palpable 15 cm below the xiphoid, but the spleen was not palpable.

Routine blood, kidney function, and coagulation function tests as well as the levels of tumor markers such as alpha-fetoprotein (AFP; 2.7 ng/mL, reference range 0-20 ng/mL), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA; 0.71 ng/mL, reference range 0-5 ng/mL), and CA19-9 (2.39 ng/mL, reference range 0-37 ng/mL) were all within normal ranges. The C-reactive protein level was mildly elevated (8.25 mg/L, reference range 0-8 mg/mL). The liver function test revealed mildly elevated gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and alkaline phosphatase (gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, 309 IU/L, reference range 10-60 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase, 182 IU/L, reference range 42-125 IU/L). The hepatitis A-E markers were all negative.

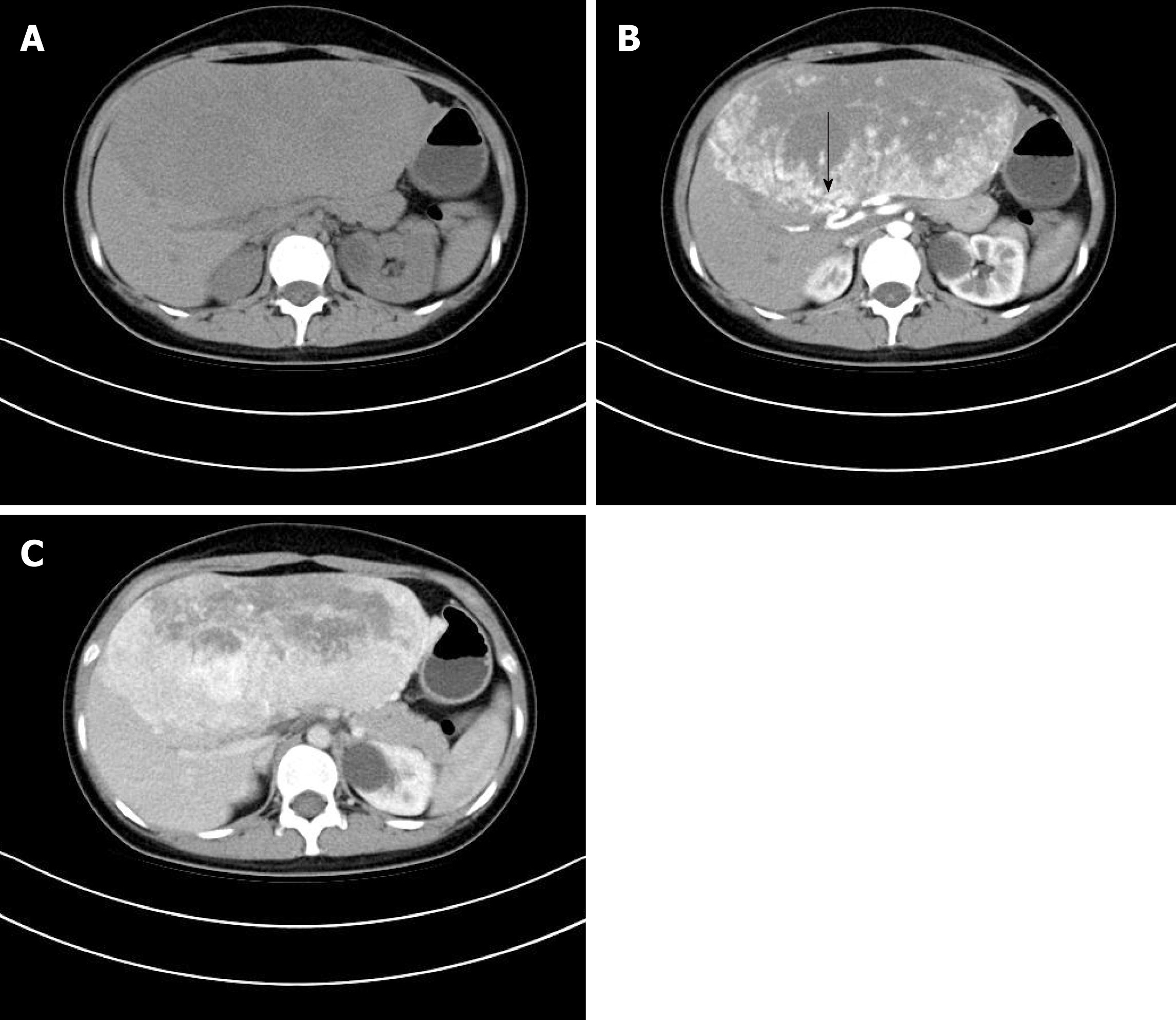

A CT scan performed at our hospital revealed a giant hepatic tumor measuring 22 cm × 20 cm × 10 cm, which completely replaced the left hepatic lobe. On non-contrast enhanced CT, the tumor showed a heterogeneous hypodensity, with a clear boundary (Figure 1A). On the contrast-enhanced CT, the tumor presented with patchy or nodular enhancement and the subcapsular feeding arteries were visible in the arterial phase (Figure 1B, arrow), which became intensified and hyper-attenuated in the portal phase (Figure 1C). However, some regions of the tumor were not enhanced in the arterial and portal phases.

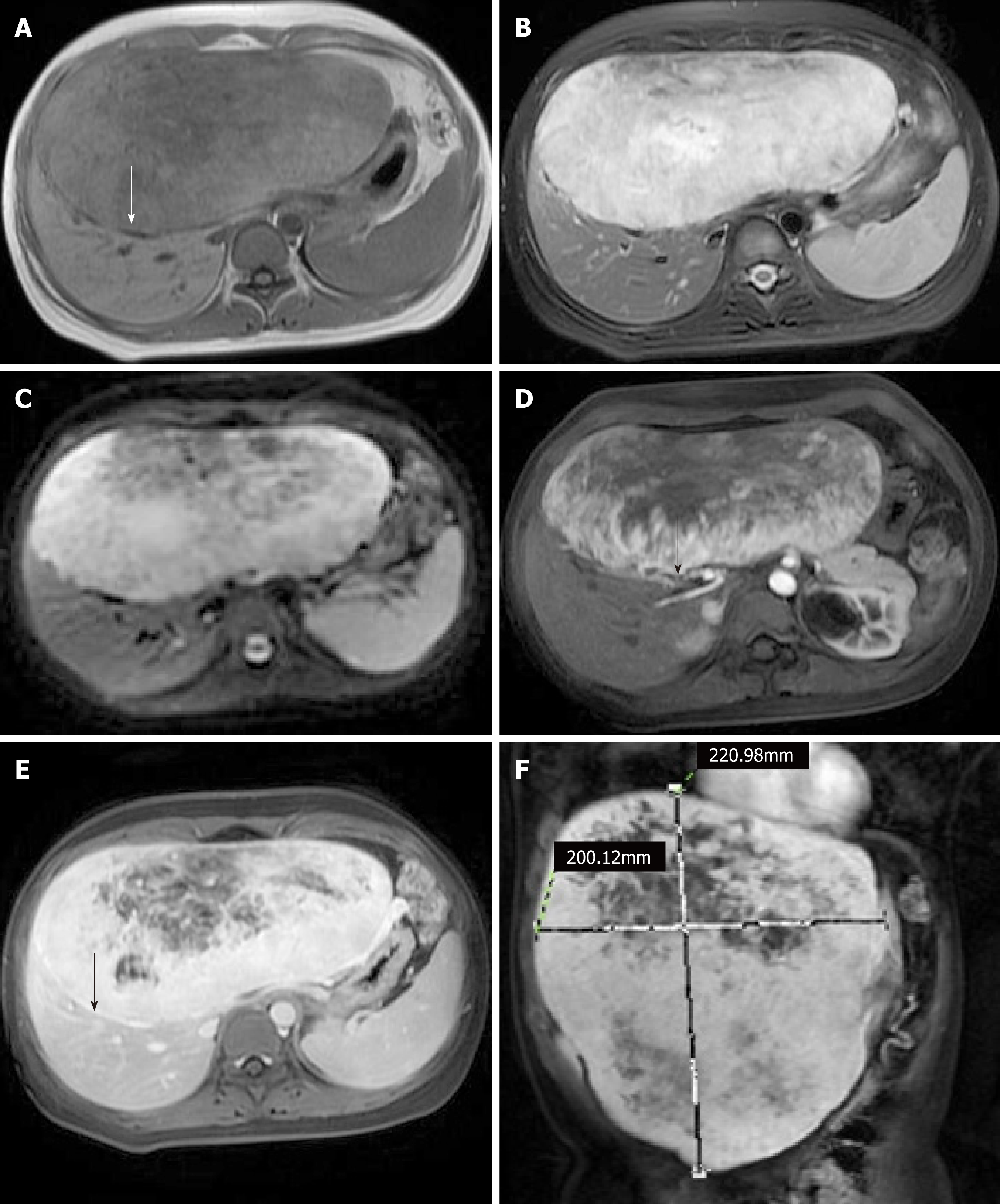

To further diagnose the patient’s condition, MRI was also performed. On T1-weighted MR images, the tumor appeared heterogeneous hypointense with a complete capsule (Figure 2A, arrow). On T2-weighted MR images, diffusion-weighted imaging, and multiplanar reconstruction images, the tumor appeared heterogeneous hyperintense (Figure 2B, 2C, and 2F). Following an injection of Gd-DTPA, the tumor presented with heterogeneous enhancement and the subcapsular feeding arteries were also visible in the arterial phase (Figure 2D, arrow). In the delayed phase, the tumor had more intense enhancement over a larger range than in the arterial phase, and the capsule was significantly enhanced (Figure 2E, arrow).

Based on these imaging manifestations, the tumor was initially diagnosed as an HCA.

The patient had surgical indications because of the giant tumor size and the risk of rupture and hemorrhage. To examine if the remnant liver weight could meet the needs of the patient’s body, we performed a preoperative assessment by CT. The results showed that the remnant liver weight (>500 g, patient’s weight was 50 kg) could meet the needs of the patient’s body. Therefore, surgery was performed, and the patient underwent surgery for extracapsular blunt separation with vascular isolation of the liver. Finally, the tumor was completely resected.

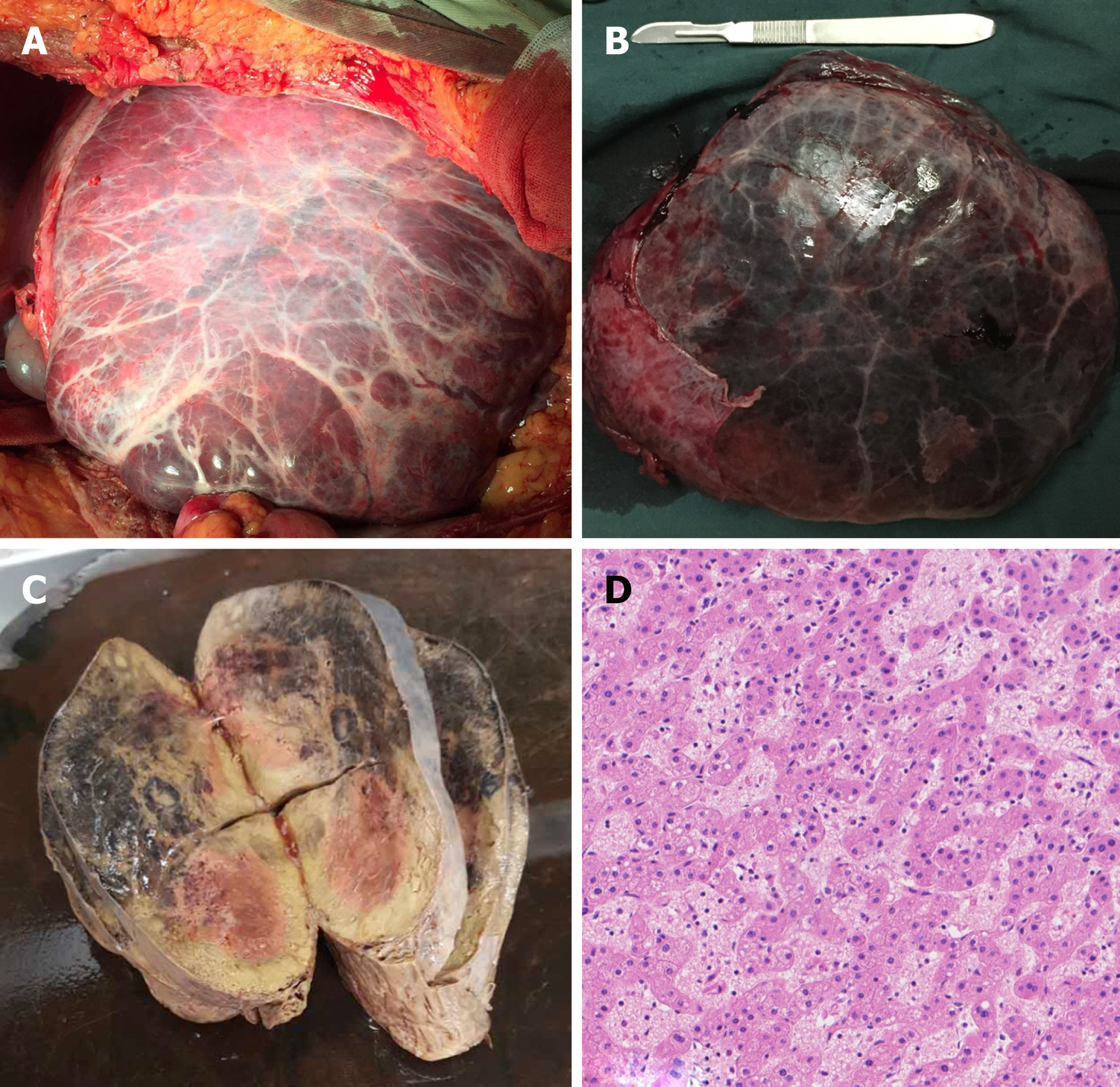

The patient recovered without complications. The hepatectomy specimen presented as a well-defined grayish yellow tumor with large surface vessels and a complete fibrous capsule, and varying degrees of hemorrhage and necrosis could be observed in the center of the tumor (Figure 3A-C). Microscopically, normal hepatic lobule structures were not found in the tumor, and the hepatocytes contained uniform magnitude without mitotic figures and thus resembled normal hepatocytes. Hepatic cords of the tumor comprised one or two layers of cells. Hyperemia edema was found in the tumor mesenchyme with scattered lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. In parts of the liver sinusoid, obvious dilation, hyperemia, and hemorrhages could be observed. There was no obvious cirrhosis and no dilated bile ducts were found. The tumor was pathologically diagnosed as an HCA (Figure 3D).

Now, the young woman is working and living normally and has not relapsed during a year of re-examinations.

HCA is occult at onset and lacks of specific clinical manifestations and laboratory examination findings. Since most scholars are cautious about liver biopsy, the preoperative diagnosis of HCA mainly depends on imaging examinations. However, the imaging manifestations of HCA are so diverse that the misdiagnosis rate is very high.

On non-contrast CT, typical HCA appears isodense or slightly hypodense, with a clear boundary. However, HCA appeared hyperdense under the background of the fatty liver. Large HCA could oppress the adjacent hepatic parenchyma to form a capsule, but the capsule is not easily visible. HCA easily leads to bleeding and necrosis, and the areas of hemorrhage show a hyperdensity in the acute or subacute phase, while the areas of old hemorrhagic necrosis show a hypodensity. On contrast-enhanced CT, the whole tumor appears homogeneously hyperdense in the arterial phase[11], but the incidence of this characteristic appearance gradually declines as the diameter increases. Hemorrhagic necrotic areas are not enhanced. Sometimes, the subcapsular feeding arteries can be seen[12]. In the portal and delayed phases, typical HCA appears isodense or slightly hypodense[11].

On MRI, there are several heterogeneous signal ranges for most of HCA. For HCA, the fat component and short-term hemorrhage areas appear hyperintense, and old hemorrhage and necrotic areas appear hypointense on T1-weighted MR images. Large HCA tends to compress the adjacent liver parenchyma and form a pseudocapsule, and the low-signal capsule at the lesion edge on T1-weighted MR images is the most obvious, showing an annular hypointensity. The mixed signals on T2-weighted MR images are predominantly slightly hyperintense. Dynamic gadolinium-enhanced gradient-echo MR imaging, like dynamic CT, can reflect the blood supply of HCA. The enhancement characteristics of HCA are closely related to the genotype/phenotype[13,14]. Subtype H-HCA presents as slightly heterogeneous enhancement in the arterial and portal phases and hypointense enhancement in the delayed phase, which is predominantly related to the fatty degeneration, lack of inflammatory cells, and dilated sinusoid. Subtype b-HCA presents as highly heterogeneous enhancement in the arterial and portal phases and heterogeneous hypointense enhancement in the delayed phase. The enhancement is characterized by very heterogeneous enhancement and rapid clearance in some areas of the lesion, which is related to the presence of heteromorphic cells and acinar cells. Subtype I-HCA mainly presents as significant enhancement in the arterial phase and persistent enhancement in the portal and delayed phases, which is related to the pathological basis of inflammatory cell infiltration and blood sinus dilatation.

HCA should be differentiated from HCC, focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH), hepatic angioleiomyoma (HAML), and hepatic hemangioma (HCH)[15-17]. HCC is usually associated with hepatitis and cirrhosis, demonstrates expansive growth, oppresses all surrounding tissues, and forms pseudocapsules. Serum AFP levels are significantly elevated in most cases. Contrast-enhanced scans suggest the enhancement characteristics of fast-in and fast-out.

FNH is a hypervascular tumor that mainly occurs in young women, without a capsule or hemorrhagic necrosis. On non-contrast enhanced CT scans, FNH appear iso-or slightly hypodense. On the contrast-enhanced CT, the enhancement is characterized by uniform enhancement except in scar tissue. Some lesions may show a supply artery located at the periphery or center of the lesion. FNH shows an iso-or slightly hypodensity in the portal and delayed phases, and delayed enhancement of the central scar is characteristic[18]. On T1-weighted MR images, FNH shows an isointense or slightly reduced signal and the center scar shows a reduced signal. On T2-weighted MRI images, FNH shows an isointensity or hyperintensity, and the center scar shows an elevated signal.

HAML is a rare benign, mesenchymal tumor that commonly occurs in young women, without hepatitis or cirrhosis. HAML is composed of different proportions of adipose tissues, thick-walled blood vessels, and smooth muscle cells, and the imaging features depend on the proportion of adipose tissues and abnormal blood vessels. Contrast-enhanced scans of HAML show hypervascular lesions with a point-strip vascular image and a focal or patchy fat component. However, the differential diagnosis of HAML from other fat-containing and hypervascular lesions is very difficult in fact. Recent research has shown that the presence of an early drainage vein is anticipated as a useful feature for distinguishing HAML from HCA[19].

HCH is the most common benign tumor that is mainly seen in adult females, without hepatitis, cirrhosis, or a capsule, but with a central scar. Contrast-enhanced scans suggest the characteristics of fast-in and slow-out, and a central scar without enhancement. The presence of an extremely bright signal on T2-weighted MR images is helpful in distinguishing HCH from HCA.

In our case, the patient’s tumor was found by physical examination without etiology. The CT and MRI findings presented as the enhanced features of fast-in and slow-out. Some unenhanced areas suggested hemorrhagic necrosis. The tumor-feeding arteries were connected to the markedly enhanced lesions in the arterial phase. Ichikawa et al[20] reported that this sign is the characteristic manifestation of HCA. Moreover, the capsule of the tumor was especially prominent on the T1-weighted MR images and showed marked enhancement in the delayed phase. Studies[21,22] have shown that these features are the characteristic imaging manifestations of HCA. Based on the above imaging findings, the tumor was initially identified as an HCA and subsequently confirmed pathologically.

We report a case of giant HCA of the left liver in a young woman. Our case highlights the importance of a combination of contrast-enhanced CT and MRI in the preoperative diagnosis of HCA. We expect that a detailed description of this case will provide valuable resources for the future diagnosis of HCA.

We wish to acknowledge Ya-Wei Yu and Quan Zhou (Department of Pathology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Jiaxing University, Jiaxing) for her support on this case in pathology.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: El-Razek AA, Ribeiro MA S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Haring MPD, Gouw ASH, de Haas RJ, Cuperus FJC, de Jong KP, de Meijer VE. The effect of oral contraceptive pill cessation on hepatocellular adenoma diameter: A retrospective cohort study. Liver Int. 2019;39:905-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bioulac-Sage P, Balabaud C, Zucman-Rossi J. Focal nodular hyperplasia, hepatocellular adenomas: past, present, future. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:355-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kato K, Abe H, Hanawa N, Fukuzawa J, Matsuo R, Yonezawa T, Itoh S, Sato Y, Ika M, Shimizu S, Endo S, Hano H, Izu A, Sugitani M, Tsubota A. Hepatocellular adenoma in a woman who was undergoing testosterone treatment for gender identity disorder. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2018;11:401-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hirata E, Shimizu S, Umeda S, Kobayashi T, Nakano M, Higuchi H, Serizawa H, Iwasaki N, Morinaga S, Tsunematsu S. [Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α-inactivated hepatocellular adenomatosis in a patient with maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 3: case report and literature review]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2015;112:1696-1704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Baheti AD, Yeh MM, O'Malley R, Lalwani N. Malignant Transformation of Hepatic Adenoma in Glycogen Storage Disease Type-1a: Report of an Exceptional Case Diagnosed on Surveillance Imaging. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2015;5:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bioulac-Sage P, Sempoux C, Balabaud C. Hepatocellular adenoma: Classification, variants and clinical relevance. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:112-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Margolskee E, Bao F, de Gonzalez AK, Moreira RK, Lagana S, Sireci AN, Sepulveda AR, Remotti H, Lefkowitch JH, Salomao M. Hepatocellular adenoma classification: a comparative evaluation of immunohistochemistry and targeted mutational analysis. Diagn Pathol. 2016;11:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Klompenhouwer AJ, de Man RA, Thomeer MG, Ijzermans JN. Management and outcome of hepatocellular adenoma with massive bleeding at presentation. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4579-4586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | An SL, Wang LM, Rong WQ, Wu F, Sun W, Yu WB, Feng L, Liu FQ, Tian F, Wu JX. Hepatocellular adenoma with malignant transformation in male patients with non-cirrhotic livers. Chin J Cancer. 2015;34:217-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stoot JH, Coelen RJ, De Jong MC, Dejong CH. Malignant transformation of hepatocellular adenomas into hepatocellular carcinomas: a systematic review including more than 1600 adenoma cases. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:509-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang W, Liu JY, Yang Z, Wang YF, Shen SL, Yi FL, Huang Y, Xu EJ, Xie XY, Lu MD, Wang Z, Chen LD. Hepatocellular adenoma: comparison between real-time contrast-enhanced ultrasound and dynamic computed tomography. Springerplus. 2016;5:951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Grazioli L, Federle MP, Brancatelli G, Ichikawa T, Olivetti L, Blachar A. Hepatic adenomas: imaging and pathologic findings. Radiographics. 2001;21:877-92; discussion 892-4. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Thomeer MG, E Bröker ME, de Lussanet Q, Biermann K, Dwarkasing RS, de Man R, Ijzermans JN, de Vries M. Genotype-phenotype correlations in hepatocellular adenoma: an update of MRI findings. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2014;20:193-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Khanna M, Ramanathan S, Fasih N, Schieda N, Virmani V, McInnes MD. Current updates on the molecular genetics and magnetic resonance imaging of focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma. Insights Imaging. 2015;6:347-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Choi WT, Ramachandran R, Kakar S. Immunohistochemical approach for the diagnosis of a liver mass on small biopsy specimens. Hum Pathol. 2017;63:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yoshioka M, Watanabe G, Uchinami H, Kudoh K, Hiroshima Y, Yoshioka T, Nanjo H, Funaoka M, Yamamoto Y. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: differential diagnosis from other liver tumors in a special reference to vascular imaging - importance of early drainage vein. Surg Case Rep. 2015;1:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nagy G, Dezsõ K, Kiss G, Gerlei Z, Nagy P, Kóbori L. [Benign liver tumours - current diagnostics and therapeutic modalities]. Magy Onkol. 2018;62:5-13. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Vyas M, Jain D. A practical diagnostic approach to hepatic masses. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2018;61:2-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Iwao Y, Ojima H, Onaya H, Sakamoto Y, Kishi Y, Nara S, Esaki M, Mizuguchi Y, Ushigome M, Asahina D, Hiraoka N, Shimada K, Kosuge T, Kanai Y. Early venous return in hepatic angiomyolipoma due to an intratumoral structure resembling an arteriovenous fistula. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:700-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ichikawa T, Federle MP, Grazioli L, Nalesnik M. Hepatocellular adenoma: multiphasic CT and histopathologic findings in 25 patients. Radiology. 2000;214:861-868. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Brancatelli G, Federle MP, Vullierme MP, Lagalla R, Midiri M, Vilgrain V. CT and MR imaging evaluation of hepatic adenoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:745-750. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Katabathina VS, Menias CO, Shanbhogue AK, Jagirdar J, Paspulati RM, Prasad SR. Genetics and imaging of hepatocellular adenomas: 2011 update. Radiographics. 2011;31:1529-1543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |