Published online Dec 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i23.4004

Peer-review started: August 20, 2019

First decision: September 23, 2019

Revised: October 6, 2019

Accepted: October 15, 2019

Article in press: October 15, 2019

Published online: December 6, 2019

Processing time: 107 Days and 23.9 Hours

One of the common late sequela in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is the calcium phosphate disorder leading to chronic hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia causing the precipitation of calcium salt in soft tissues. Tumoral calcinosis is an extremely rare clinical manifestation of cyst-like soft tissue deposits in different periarticular regions in patients with ESRD and is characterized by extensive calcium salt containing space-consuming painful lesions. The treatment of ESRD patients with tumoral calcinosis manifestation involves an increase in or switching of renal replacement therapy regimes and the adjustment of oral medication with the goal of improved hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia.

We describe a 40-year-old woman with ESRD secondary to IgA-nephritis and severe bilateral manifestation of tumoral calcinosis associated with hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia and tertiary hyperparathyroidism. The patient was on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and treatment with vitamin D analogues. After switching her to a daily hemodialysis schedule and adjusting the medical treatment, the patient experienced a significant dissolution of her soft tissue calcifications within a couple of weeks. Complete remission was achieved 11 mo after the initial diagnosis.

Reduced patient compliance and subsequent insufficiency of dialysis regime quality contribute to the aggravation of calcium phosphate disorder in a patient with ESRD leading to the manifestation of tumoral calcinosis. However, the improvement of the treatment strategy and reinforcement of patient compliance enabled complete remission of this rare disease entity.

Core tip: Tumoral calcinosis, a very rare disease entity, occurred in the described patient with end-stage renal disease due to disturbed calcium phosphate metabolism and insufficient quality of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Complete remission was achieved by modification of the medical treatment and by switching to hemodialysis, which improved the dialysis quality. In general, to recuperate severe tumoral calcinosis, the treatment must be selected based on an understanding of the clinical background and the quality of the renal replacement therapy regime. In conclusion, this case report will significantly contribute to the reader’s understanding of tumoral calcinosis pathogenesis and treatment in patients with end-stage renal disease.

- Citation: Westermann L, Isbell LK, Breitenfeldt MK, Arnold F, Röthele E, Schneider J, Widmeier E. Recuperation of severe tumoral calcinosis in a dialysis patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(23): 4004-4010

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i23/4004.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i23.4004

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) is associated with significant comorbidity and mortality usually representing a condition of abnormal calcium-phosphate metabolism causing hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia with associated calcium salt deposits in soft tissues like blood vessels, visceral organs and skin[1-3]. While soft tissue calcifications in patients with ESRD is common, the prevalence of extensive periarticular cyst-like calcium salt containing space-consuming lesions in the form of tumoral calcinosis is very rare[4,5]. The pathophysiology underlying the development of this rare disease entity remains unclear. It is mostly associated with manifestation of hyperparathyroidism, hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia[6]. That said, there is evidence of hormone-independent disease onset[7]. We describe the case of a 40-year-old woman with ESRD due to IgA-type nephritis on peritoneal dialysis, who developed severe tumoral calcinosis associated with administration of vitamin D analogues, hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia and tertiary hyperparathyroidism experiencing complete remission during the next 11 mo after the modification of the treatment strategy.

A 40-year-old woman with ESRD secondary to IgA-nephritis, who had been on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) for 24 mo, was admitted to our emergency department in September 2016 with continuously worsening bilateral immobilizing hip pain since 4 mo.

Her CAPD treatment regime was as follows: Four cycles involving a total dialysate volume of 8000 mL/24 h, three daytime exchanges and one nighttime exchange. The daytime dialysate bags consisted of 1x Dianeal PDG4 1.36%, 2x Dianeal PDG4 2.27% glycose solution containing a calcium concentration of 1.25 mmol/L and 1x overnight extraneal icodextrin solution containing a calcium concentration of 1.75 mmol/L. The CAPD efficacy was measured by peritoneal Kt/V (reference range > 1.7) and was performed on weekly basis. Before the hospital admission, tests had indicated a 24-h urine output of 900 mL, 24-h ultrafiltration rate of 900 mL and a peritoneal Kt/V of 1.32 showing insufficient dialysis quality with clinical signs of uremia. The overall situation was further complicated by the fact that her medical treatment compliance was doubtful, and her peritoneal Kt/V had been successively worsening for the previous 7 mo (for instance, 5 mo before admission, peritoneal Kt/V was indicated at 1.96). For the 4 mo prior to her diagnosis, she had complained of progressive, bilateral pain and immobility of her hips and having progressive, palpable painful indurations around her gluteal and hip regions. She had been taking vitamin D analogues: 1, 25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol at a dose of 0.5 µg orally twice a week for 14 mo and cholecalciferol at a dose of 20000 IE orally every 14 d for 20 mo due to low vitamin D3 level associated with increasing parathormone levels. She had been on phosphate binders: calcium acetate with a total daily dose of 1900 mg for 26 mo and sevelamer carbonate with a total daily dose of 3200 mg for 1 mo.

Her past medical history showed preeclampsia associated with HELLP syndrome in September 2005 and usual ESRD comorbidities as follows: Renal anemia, arterial hypertension and hyperparathyroidism as well as a severe CAPD associated peritonitis (S. aureus) in December 2015.

Family history was positive for chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in her aunt and cousin.

At admission, her physical examination showed reduced mobility of her hip joints associated with swelling and tenderness on percussion.

Her laboratory findings showed increased serum calcium, phosphate and parathormone levels (Table 1). Her calcitriol level was at the lower reference range at 20 ng/mL 20 d after admission.

| Serum parameter (unit) | 28 mo before ID (start of RRT) | 10 mo before ID (on PD) | At admission ID (on PD) | 3 mo post ID (on HD) | 4 mo post ID (on HD) | 22 mo post ID (on HD) | 34 mo post ID (on HD) | Reference range |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.47 | 2.51a | 2.75a | 3.24 | 2.82 | 2.14 | 2.19 | 2.15-2.5 |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | 2.00 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.31 | 1.21 | 0.81-1.45 |

| Ca x P product (mmol2/L2) | 4.94 | 5.10 | 6.33 | 5.83 | 4.79 | 2.80 | 2.65 | b |

| Parathormone (pg/mL) | 185 | N/A | N/A | 104 | 285 | 620 | N/A | 15-65 |

| 25-OH vitamin D2/D3 (ng/mL) | 53.0 | N/A | N/A | 29.4 | 28.7 | 34.2 | N/A | 20-70 |

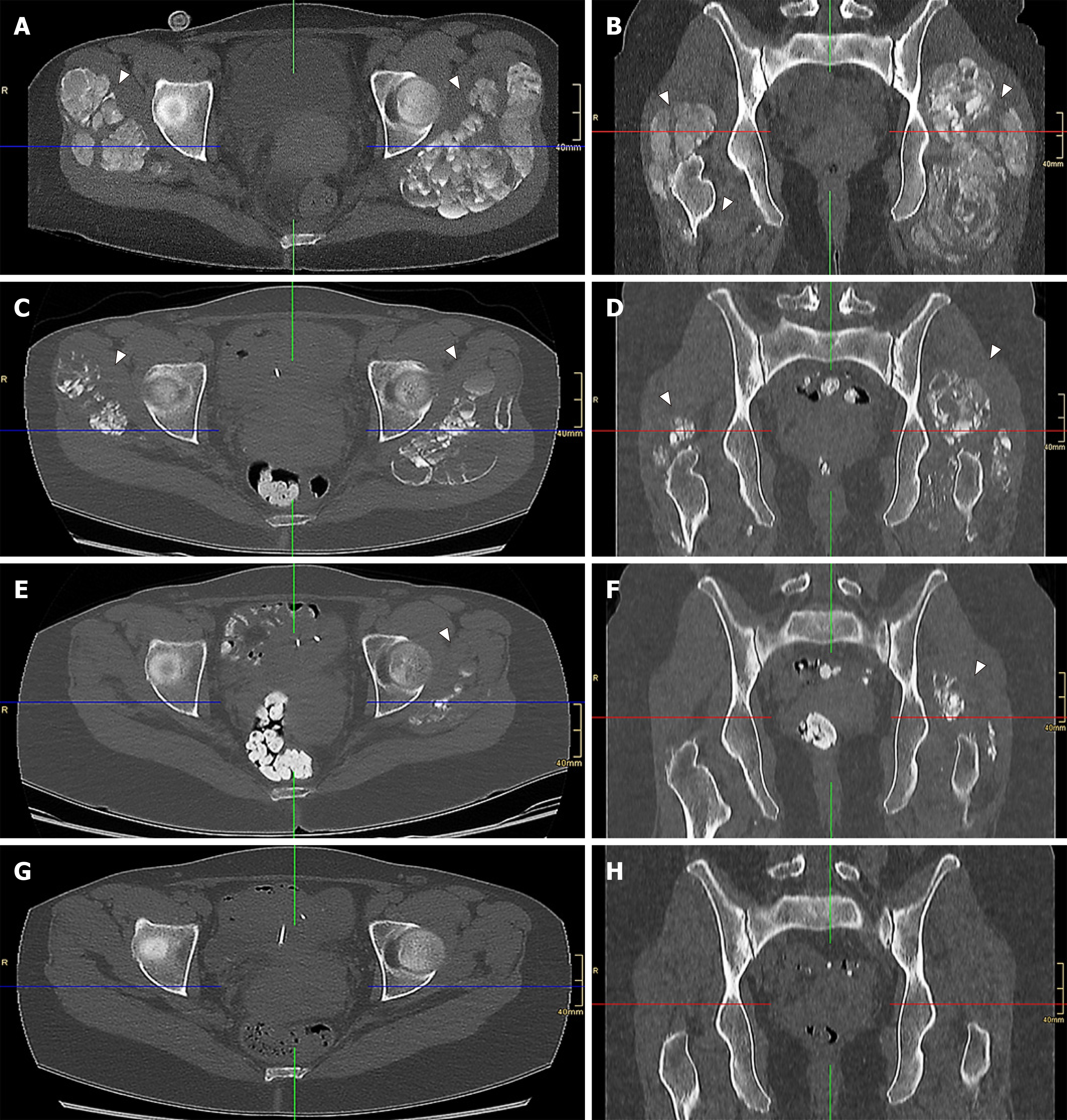

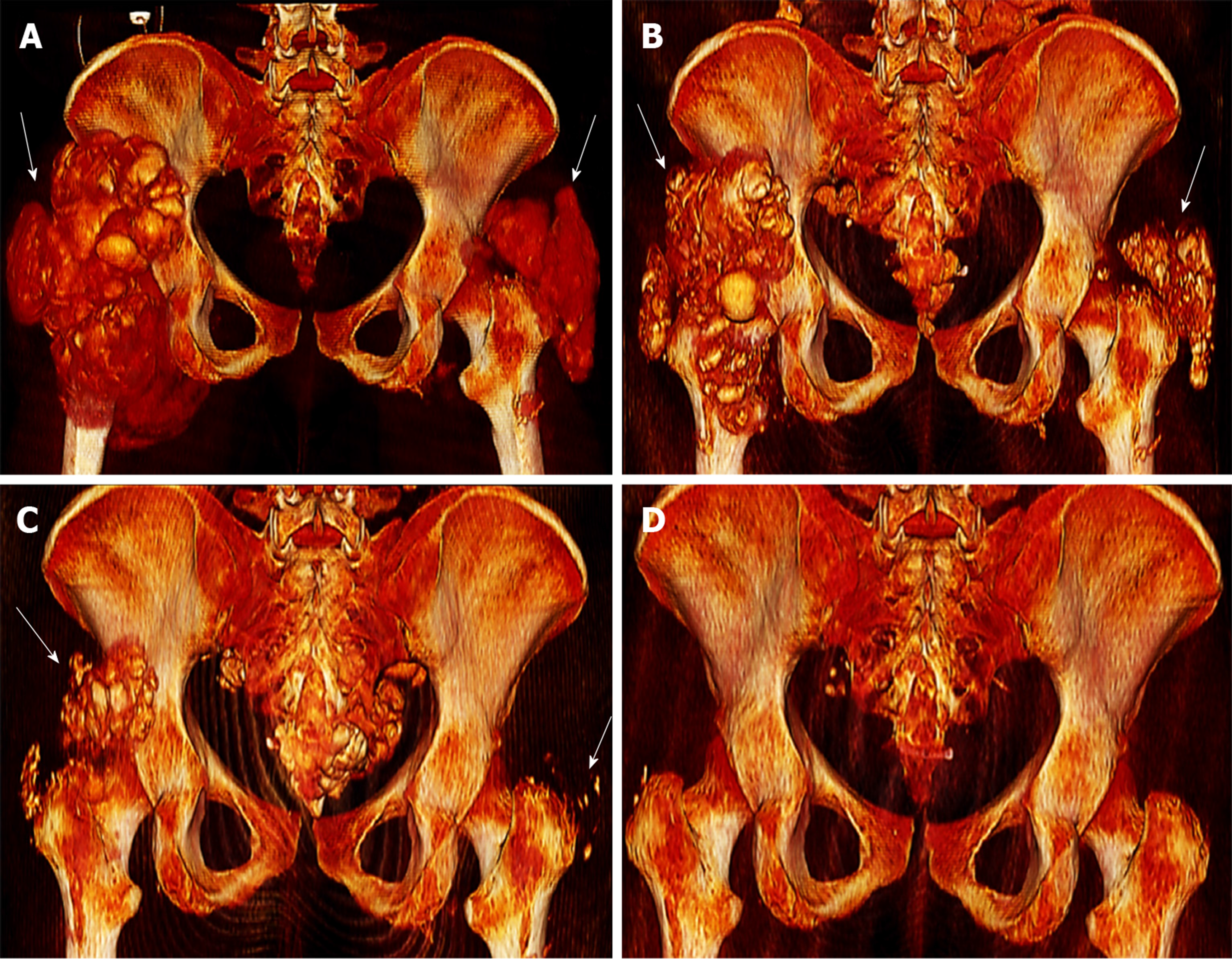

A computed tomography scan of her pelvic region at admission showed severe bilateral manifestation of tumoral calcinosis, mainly around the trochanter major (Figure 1A, 1B and Figure 2A).

Subsequently, the vitamin D analogue therapy was discontinued. She started lanthan(III)-carbonate, discontinued sevelamer carbonate and started an in-hospital low-calcium and low-phosphate diet. Furthermore, due to the severity of the clinical findings and insufficient quality of CAPD, she was instantly switched to daily hemodialysis (HD). Her HD schedule involved 5-h sessions six times weekly at a 250 mL/min blood pump speed and 500 mL/min dialysate pump speed with the following dialysate composition: Sodium 138 mmol/L, calcium 1.0 mmol/L and bicarbonate 32 mmol/L. The follow-up computed tomography scans, one at 2 mo (Figure 1C, 1D and Figure 2B) and another at 4 mo (Figure 1E, 1F and Figure 2C) after initial diagnosis, demonstrated significant improvement in her tumoral calcinosis. Based on these findings the above-mentioned HD schedule was subsequently reduced to 5-h sessions 3x weekly for the next 3 mo followed by a nighttime HD schedule of 7-h sessions 3x weekly until the present day.

The follow-up computed tomography scan at 11 mo after initial diagnosis revealed complete remission of the tumoral calcinosis (Figure 1G, 1H and Figure 2D) along with normal calcium levels. However, hyperphosphatemia and elevated parathormone levels remained. Due to persistent therapy-refractory tertiary hyperparathyroidism and despite the therapy with etelcalcetid and cinacalcet hydrochloride, the patient underwent a total parathyroidectomy 22 mo after the initial diagnosis and started calcium acetate with a total daily dose of 1900 mg with adequate response to treatment. Follow-up with the patient has, at the time of publication, reached a total of 34 mo with normal range values of calcium, phosphate, Ca x P product, parathormone and calcitriol. The patient is currently listed for kidney transplantation.

The final diagnosis of the patient was secondary tumoral calcinosis (calcinosis of chronic renal failure) due to ESRD associated with tertiary hyperparathyroidism, hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia.

Right after the diagnosis of the tumoral calcinosis the patient was switched from PD to daily HD (5-h session 6x/wk for 4 consecutive mo) and subsequently reduced to 5-h sessions 3x weekly for the next 3 mo followed by a nighttime HD schedule of 7-h sessions 3x weekly. The medication was adjusted as follows: Vitamin D analogues and sevelamer carbonate were discontinued; lanthan(III)-carbonate was started upon the diagnosis and continued until parathyroidectomy and then subsequently switched to calcium acetate (continued until time of publication); in addition etelcalcetid was commenced 13 mo after diagnosis but did not have the desired effect and was replaced after 2 mo with cinacalcet hydrochloride, which continued until the parathyroidectomy.

At the time of publication, follow-up with the patient had reached a total of 34 mo. The patient experienced complete remission of tumoral calcinosis 11 mo after the initial diagnosis. The patient underwent a total parathyroidectomy due to persistent therapy-refractory tertiary hyperparathyroidism 22 mo after the initial diagnosis and is currently listed for a kidney transplantation.

The tumoral calcinosis (calcinosis of chronic renal failure) represents a benign rare disease entity in ESRD patients and is associated with hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia and hyperparathyroidism leading to widespread calcifications of soft tissues mostly in the periarticular regions of the large joints[8]. The pathophysiology of tumoral calcinosis remains mostly unclear. ESRD patients often experience dysregulation of calcium phosphate metabolism due to impaired renal phosphate excretion and vitamin D activation causing hyperparathyroidism, elevated calcium phosphate product and the precipitation thereof in soft tissues[6].

In our case, the patient developed tumoral calcinosis due to the insufficient quality of CAPD, doubtful compliance and typical late sequela of calcium phosphate metabolism possibly aggravated by vitamin D3 administration. In addition, a concurrent rapid decrease of PD quality might have been caused by possible calcification of peritoneal microvasculature. Being on CAPD treatment, the patient had a high calcium phosphate product of 6.33 mmol2/L2 (normal range: < 4.5 mmol2/L2) and a high parathormone level at admission. The switch of PD to HD led to a rapid and sufficient decrease of calcium phosphate product indicating its sufficient clearance by HD. The most likely explanation is that decreased intradialytic calcium and phosphate levels caused the mobilization of calcium located in soft tissue calcification leading to disaggregation of tumoral calcinosis in a short time with the achievement of a complete remission. However, the tertiary hyperparathyroidism remained present even several months after successful treatment with normal serum calcium levels and was finally treated by a parathyroidectomy.

We report a patient with ESRD and severe tumoral calcinosis who achieved complete remission. It is important for renal health care providers to recognize that ESRD patients may develop this rare disease entity based on reduced patient compliance and subsequent insufficiency of dialysis regime quality contributing to the aggravation of calcium phosphate disorder in such patients. However, improvement of the treatment strategy and reinforcement of patient compliance can enable the complete remission of this rare disease entity.

We are grateful to the patient for her contribution. We thank Patrick Salisbury for proofreading the manuscript.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Pedersen EB, Al-Haggar M, Yorioka N, Eroglu E S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Walsh JS, Fairley JA. Calcifying disorders of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:693-706. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Goodman WG, Goldin J, Kuizon BD, Yoon C, Gales B, Sider D, Wang Y, Chung J, Emerick A, Greaser L, Elashoff RM, Salusky IB. Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1478-1483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1961] [Cited by in RCA: 1943] [Article Influence: 77.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Muntner P, Coresh J, Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Perneger TV. History of myocardial infarction and stroke among incident end-stage renal disease cases and population-based controls: an analysis of shared risk factors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:323-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Eisenberg B, Tzamaloukas AH, Hartshorne MF, Listrom M, Arrington ER, Sherrard DJ. Periarticular tumoral calcinosis and hypercalcemia in a hemodialysis patient without hyperparathyroidism: a case report. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:1099-1103. |

| 5. | Franco M, Van Elslande L, Passeron C, Verdier JF, Barrillon D, Cassuto-Viguier E, Pettelot G, Bracco J. Tumoral calcinosis in hemodialysis patients. A review of three cases. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1997;64:59-62. [PubMed] |

| 6. | National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:S1-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 904] [Cited by in RCA: 869] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kamar FB, Mann B, Kline G. Sudden onset of parathyroid hormone-independent severe hypercalcemia from reversal of tumoral calcinosis in a dialysis patient. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17:137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Olsen KM, Chew FS. Tumoral calcinosis: pearls, polemics, and alternative possibilities. Radiographics. 2006;26:871-885. [PubMed] |