Published online Nov 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i22.3718

Peer-review started: August 21, 2019

First decision: September 9, 2019

Revised: October 8, 2019

Accepted: October 15, 2019

Article in press: October 15, 2019

Published online: November 26, 2019

Processing time: 96 Days and 7.6 Hours

Many patients have inadequate long-term analgesia, respiratory distress, and hypoxemia due to a long-standing substantial smoking history or the presence of primary pulmonary diseases; analgesic treatment is not valid in these patients. Even if the imaging findings of rib fractures are relatively mild, rib fractures may cause severe position limitation, respiratory distress, and hypoxemia.

To investigate the curative effect of surgical treatment for patients with severe non-flail chest rib fractures.

A total of 78 patients from our hospital with severe noncontinuous thoracic rib fractures from September 2016 to September 2018 were enrolled in our study. Thirty-nine patients underwent surgical treatment, and 39 underwent conservative treatment. The surgical treatment group received surgery performed with titanium plates, and the screws were inserted with open reduction and internal fixation. The conservative treatment group received analgesia and symptomatic treatment. The pain scores at 72 h, 1 wk, 2 wk, 4 wk, 6 wk, 3 mo, and 6 mo were compared, and the SF-36 quality of life scores were compared atthe 3rd and 6th months.

Pain relief in the surgical group was significantly better than that in the conservative group at each time point (72 h, 1 wk, 2 wk, 4 wk, 6 wk, 3 mo, and 6 mo after surgery, P < 0.001). ( The SF-36 scores were significantly higher in the surgical group than in the conservative group at 1 mo and 6 mo (P < 0.05).

Patients with severe non-flail chest rib fractures have a better quality of life following surgical treatment than following conservative treatment, and surgical treatment is also useful for relieving pain. We should pay more attention to the physiological functions and clinical manifestations of patients with severe rib fractures. In patients with non-flail chest rib fractures, surgical treatment is feasible and effective.

Core tip: Patients with severe non-flail chest rib fractures have a better quality of life following surgical treatment than following conservative treatment, and surgical treatment is also useful for relieving pain. We should pay more attention to the physiological functions and clinical manifestations of patients with severe rib fractures. In patients with non-flail chest rib fractures, surgical treatment is feasible and effective.

- Citation: Zhang JP, Sun L, Li WQ, Wang YY, Li XZ, Liu Y. Surgical treatment ofpatients with severe non-flail chest rib fractures. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(22): 3718-3727

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i22/3718.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i22.3718

A rib fracture is caused by a large force impacting the chest wall and is a typical chest injury, accounting for 40%-80% of chest traumas[1,2]. The severity of injury varies with the number of rib fractures, the presence or absence of angulation, and the age and physical condition of the patient; the injury may be accompanied by severe complications (pneumothorax, hemothorax, pulmonary contusion, pneumonia, and other critical organ damage), and posttraumatic mortality is also relatively high[3,4].

There are two types of treatments for rib fractures: Surgical treatment and conservative treatment. Surgical treatment involves rib fracture internal fixation in the literature, and this method is often reported in select patients with injuries to the flail chest[5]. Conservative treatment includes analgesia and ventilator support. The clinical manifestations of patients with rib fractures vary widely. Some patients who meet the diagnostic criteria for image of flail chest have no abnormal breathing, have satisfactory pain management, and have mild respiratory complications.

In contrast, many patients have inadequate long-term analgesia, respiratory distress, and hypoxemia due to a long-standing substantial smoking history or the presence of primary pulmonary diseases; analgesic treatment is not valid in these patients. Even if the imaging findings of rib fractures are relatively mild, rib fractures may cause severe position limitation, respiratory distress, and hypoxemia. Even further, mechanical ventilation may be needed, so the "clinical flail chest" condition should receive more attention[6].

In clinical work, we found that many patients who did not meet the diagnostic criteria fora sacral chest but met the "clinical flail chest" criteria were limited by severe pain before surgery, but they were able to get out of bed on the first day after surgery. The recovery process was very smooth. The postoperative follow-up satisfaction was also high, and the surgical results were very significant. Therefore, we designed this study that included78 patients with severe non-continuous thoracic rib fractures; 39 patients underwent surgical treatment, and 39 patients underwent conservative treatment and were considered as acontrol group. The pain scores before and after surgery and the SF-36 scores were used to evaluate the curative effects of surgery compared with those of conservative treatment.

A total of 78 patients with rib fractures who were treated at our hospital from September 2016 to September 2018 were enrolled, and there were 39 patients in the surgical group and 39 patients in the conservative treatment group.

The inclusion criteria for the study were non-flail unilateral rib fractures of three or more severely displaced fractures, defined as bicortical displacement, and the absence of sternal fractures and costal cartilage fractures. The flail chest was defined as three or more contiguous ribs fractured in two or more places.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) Age less than 18 years old; (2) Chest trauma associated with severe craniocerebral injury, abdominal organ injury, severe spinal trauma, or others; (3) Rib fracture combined with severe pulmonary laceration, bronchial rupture, massive hemothorax, diaphragmatic rupture, acute chest wall defect, open thoracic wall fracture, or other severe thoracic organ damage; (4) Bacteremia, chest wall infection, or chest infection; (5) A serious medical disease that is a contraindication for general anesthesia, such as a new cerebral infarction, myocardial infarction, and hemorrhagic syndrome; and (6) An illness that may cause a severe decline in patient quality of life and is not included in the study inclusion criteria, including a severe pelvic fracture, a severe lower limb fracture, a severe brain infarction sequela, a poorly controlled chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiac insufficiency. The hospital's ethics committee approved the study, and the patients were fully informed, agreed to the treatment, and signed an informed consent form.

Immediately after enrollment in the study, the patient’s data were collected, and routine treatment was given. The surgical treatment group under went the relevant examination, and surgery was performed with a titanium plate and by open reduction and internal fixation of the screws. The conservative treatment group was routinely given nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain, and for patients with poor pain management, the medication was gradually escalated to opioid analgesics; some patients underwent thoracic epidural block, thoracic paravertebral block, or intercostal block[7,8].

The pain scores at 72 h, 1 wk, 2 wk, 4 wk, 6 wk, 3 mo, and 6 mo after the operation were observed and compared with those of the conservative treatment group. The quality of life scores for the two groups were recorded at 3 mo and 6 mo after the surgery.

Patient pain was scored using a digital pain scale: 0: no pain; 1-3: mild pain; 4-6: moderate pain; and 7-10: severe pain.

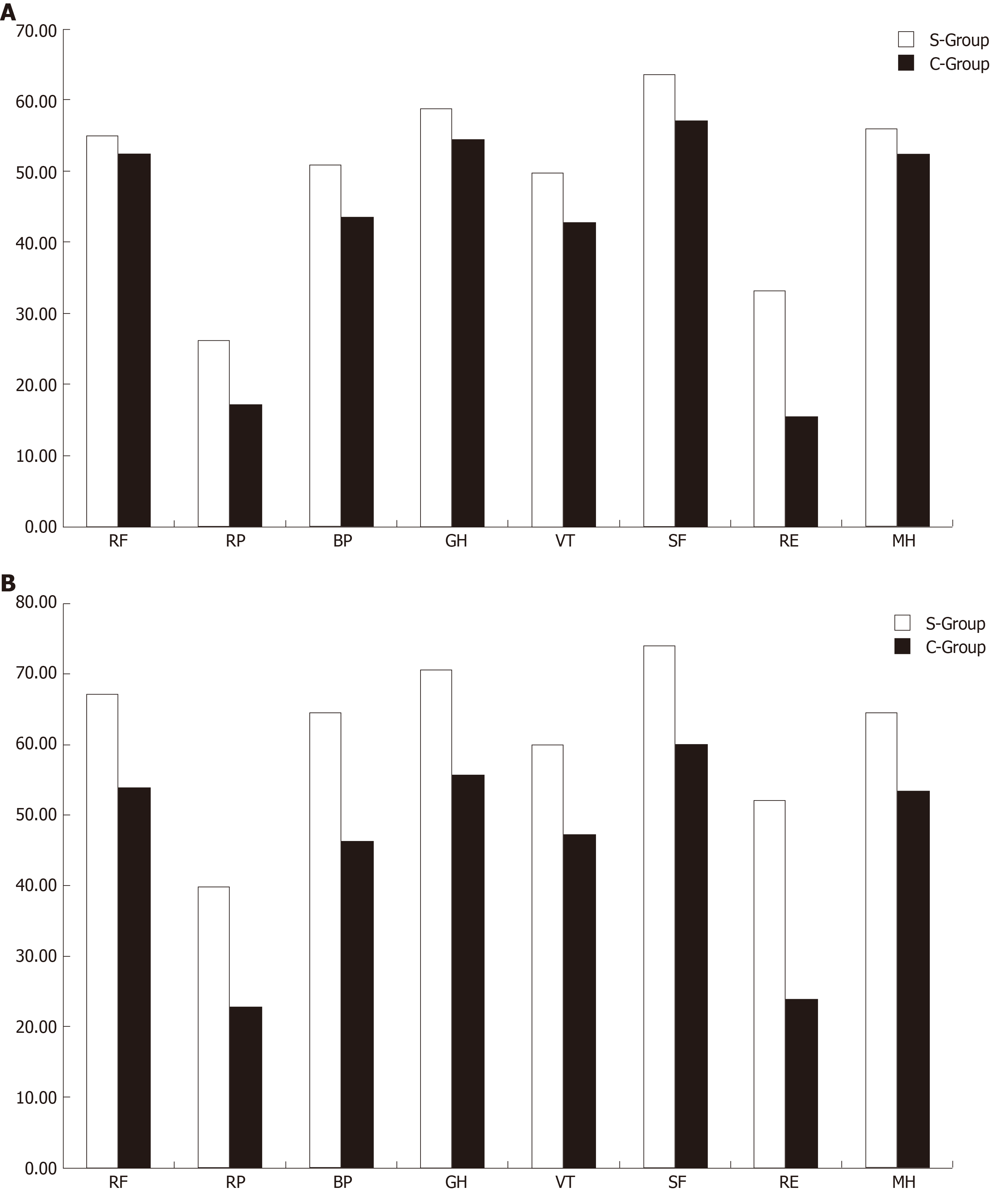

The SF-36 (36-item Short Form questionnaire) was developed by the Medical Outcomes Study group[9]. This questionnaire assesses the quality of life of patients with 36 items addressing the following eight dimensions: Physical functioning, physical role functioning, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional functioning, and mental health. Each domain has a score of 0 to 100 points. A higher score corresponds to a higher quality of life.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0. Measurement data are expressed as the mean ± SD. The SF-36 scores of the two groups were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The pain scores of the two groups were compared using repeated-measures analysis of variance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 78 patients were enrolled. The operation group enrolled 28 males and 11 females with an average age of 48.7 years. The conservative treatment group contained 29 males and 10 females with an average age of 50.2 years. The average number of rib fractures in different locations was 5.6 (1.4) vs 5.4 (1.4). The average number of rib fractures in different locations was 5.1 (1.3) vs 4.9 (1.2). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups (P > 0.05, Table 1).

| Clinical information | Surgery group (n = 39) | Conservative group (n = 39) | P value |

| Sex | 0.071 | ||

| Male | 28 | 29 | |

| Female | 11 | 10 | |

| Age | 48.7 (9.6) | 50.2 (10.1) | 0.059 |

| Rib fracture (root) | 5.1 (1.3) | 4.9 (1.2) | 0.057 |

| Rib fracture | 5.6 (1.4) | 5.4 (1.4) | 0.054 |

| Chest associated injury | 0.065 | ||

| Pulmonary contusion | 27 | 25 | |

| Simple blood chest | 15 | 14 | |

| Blood pneumothorax | 8 | 6 | |

| Average chest cumulative AIS1 | 3 | 3 | 0.985 |

| Chest injury2 | 0.073 | ||

| Clavicle and upper limb fracture | 5 | 5 | |

| Mild brain injury | 2 | 3 | |

| Hepatic contusion | 1 | 1 | |

| Spleen contusion | 0 | 1 | |

| Tobacco use | 16 | 15 | 0.075 |

The average number of fixed fractures in the operation group was 4.744 ± 0.715, the total incision length was 7.667 ± 1.143 cm, the operation time was 60.385 ± 14.345 min, the intraoperative blood loss was 38.461 ± 21.094 mL, and the time to chest wall drainage extraction was 30.769 ± 9.045 h. The chest drainage time was 34.154 ± 8.937 h, and the amount of thoracic and chest wall drainage was 168.462 ± 54.413 mL (Table 2). There were no perioperative deaths.

| Surgical parameter | mean ± SD |

| Fixed | 4.744 ± 0.715 |

| Total incision length (cm) | 7.667 ± 1.143 |

| Operation time (min) | 60.385 ± 14.345 |

| Intraoperative bleeding (mL) | 38.461 ± 21.094 |

| Time to chest wall drainage extraction (h) | 30.769 ± 9.045 |

| Thoracic + chest wall drainage (mL) | 168.462 ± 54.413 |

| Time to chest drainage extraction(h) | 34.154 ± 8.937 |

In the operation group, two patients had postoperative venous thrombosis of the lower extremities, and no pulmonary embolism occurred. There were no incisions or deep tissue infections after the operation, and the rib plates were removed before the fracture healed. Before the first stage of healing, three patients with incisions had localized fat liquefaction or aseptic necrosis of muscle tissue. Considering that postoperative muscle soft tissue injuries heal poorly, only partial debridement was used, and no antibiotics were used; a smooth process of healing occurred.

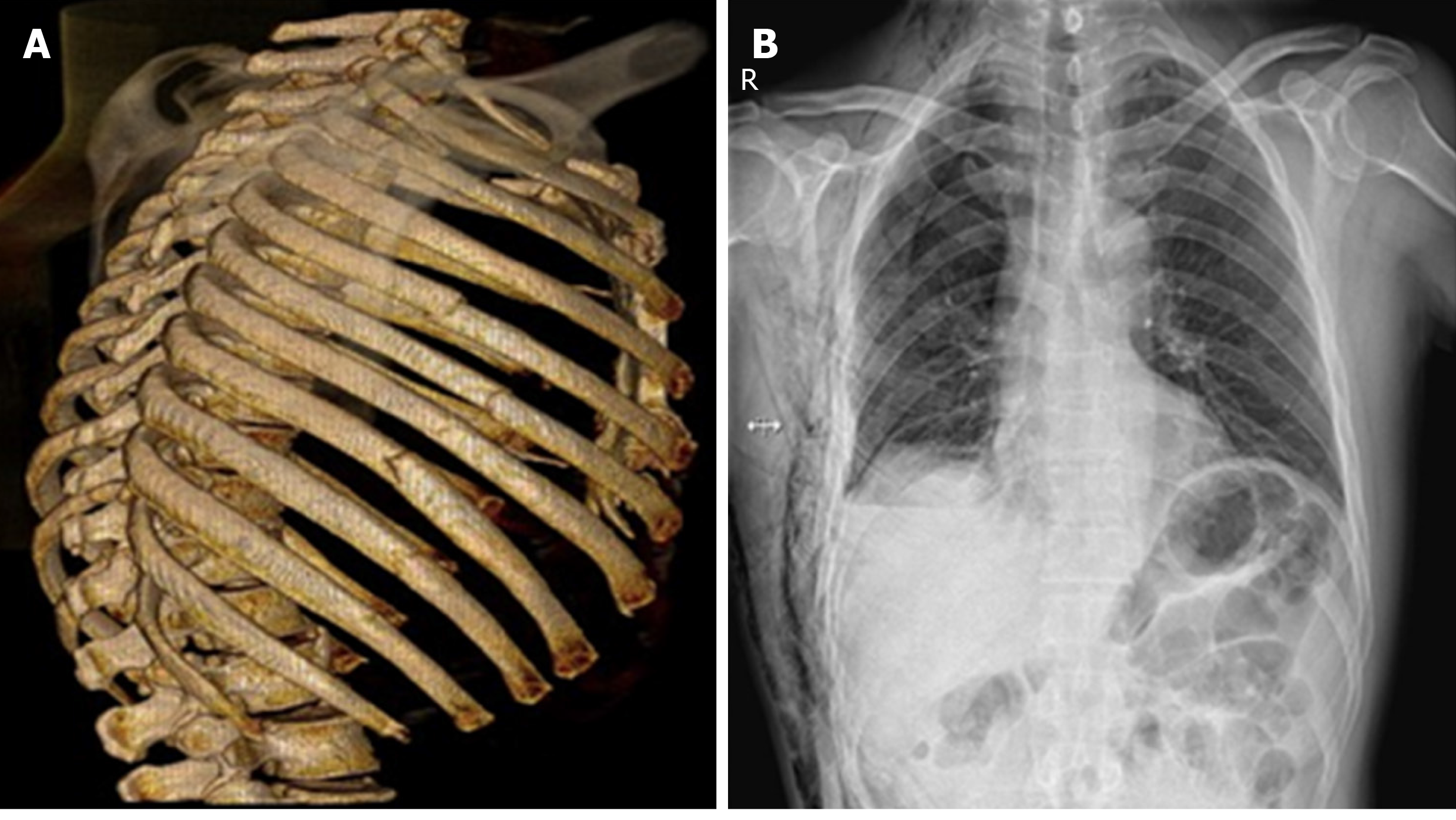

Postoperative follow-ups by chest radiographs or chest computed tomography scans did not show bone nonunion, thoracic deformities similar to the preoperative deformities, or rib plate fractures (Figure 1). All patients in this study had no postoperative thoracic deformity or abnormal breathing, and respiratory function was significantly improved after treatment.

The level of physical activity in daily life was significantly higher after 3 mo in the surgical group than in the conservative treatment group (27/39 vs 19/39, P < 0.05). After 6 mo of treatment, the rate of pre-injury work in the traditional group was 64.10% (25/39), and the rate of pre-injury work in the surgical group was 94.87% (37/39). Compared with conservative treatment, surgical treatment can achieve a higher quality of life in the medium and long term.

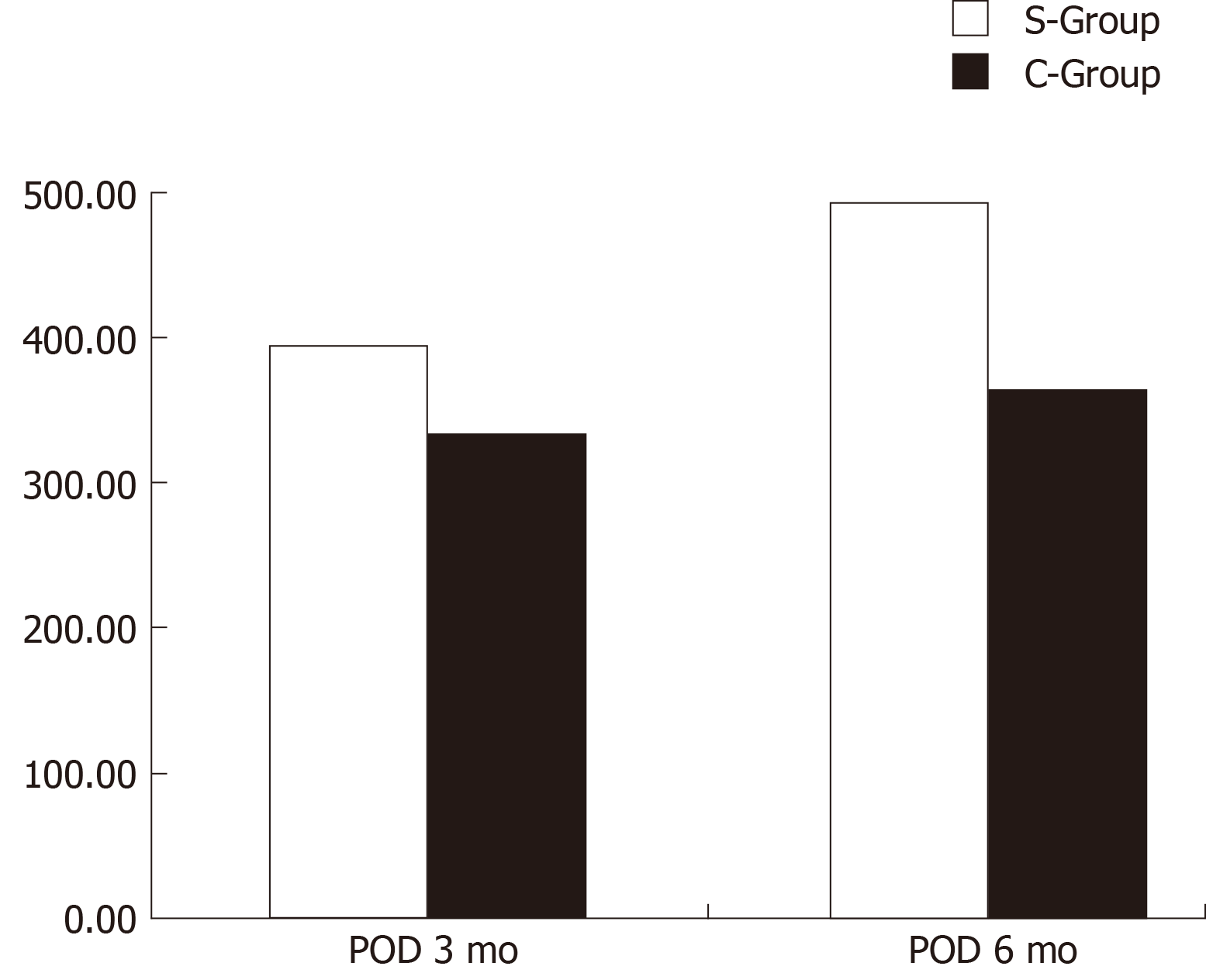

It can be seen from Figure 2A and B that the quality of life scores of the operation group were higher than those of the conservative group in all eight dimensions, at both 3 mo and 6 mo after the procedure. The total SF-36 scores in the operation group were higher than those in the conservative group at 3 mo and 6 mo after surgery; these results indicate that the recovery rate of the patients in the operation group was faster and that short-term and long-term effects were better than those of the patients in the conservative group (Figure 3). To prove whether the results were statistically significant, we performed a Wilcoxon rank-sum test on the two groups of data (Table 3). The indexes of the operation group were better than those of the conservative group at 3 mo and 6 mo after surgery, and there was statistical significance (P < 0.05).

| Dimension | Surgery group (n = 39) | Conservative group (n = 39) | Z/t | P value |

| PF | ||||

| Postoperative 3 mo | 52.44 (6.77,60.00) | 50.00 (50.00,50.00) | -1.810 | 0.070 |

| Postoperative 6 mo | 65.00 (65.00,70.00)d | 55.00 (50.00,55.00)d | -6.850 | 0.000b |

| RP | ||||

| Postoperative 3 mo | 25.00 (0.00,50.00) | 25.00 (0.00,25.00) | -2.019 | 0.043a |

| Postoperative 6 mo | 25.00 (25.00,50.00)d | 25.00 (0.00,25.00)d | -3.380 | 0.001b |

| BP | ||||

| Postoperative 3 mo | 52.00 (41.00,52.00) | 41.00 (31.00,52.00) | -2.829 | 0.005b |

| Postoperative 6 mo | 62.00 (52.00,74.00)d | 41.00 (31.00,52.00)d | -5.386 | 0.000b |

| GH | ||||

| Postoperative 3 mo | 60.00 (50.00,65.00) | 55.00 (45.00,65.00) | -2.071 | 0.038a |

| Postoperative 6 mo | 72.00 (65.00,72.00)d | 55.00 (50.00,65.00)d | -5.838 | 0.000b |

| VT | ||||

| Postoperative 3 mo | 50.00 (45.00,55.00) | 40.00 (35.00,45.00) | -3.922 | 0.000b |

| Postoperative 6 mo | 60.00 (55.00,60.00)d | 45.00 (45.00,50.00)d | -6.960 | 0.000b |

| SF | ||||

| Postoperative 3 mo | 62.50 (62.50,62.50) | 62.50 (50.00,62.50) | -3.092 | 0.002b |

| Postoperative 6 mo | 75.00 (62.50,75.00)d | 62.50 (50.00,62.50)d | -5.259 | 0.000b |

| RE | ||||

| Postoperative 3 mo | 33.33 (33.33,33.33) | 0.00 (0.00,33.33) | -3.983 | 0.000b |

| Postoperative 6 mo | 66.70 (33.33,66.70)d | 33.33 (0.00,33.33)d | -4.940 | 0.000b |

| MH | ||||

| Postoperative 3 mo | 56.00 (52.00,60.00) | 52.00 (48.00,56.00) | -3.199 | 0.001b |

| Postoperative 6 mo | 64.00 (60.00,64.00)d | 52.00 (52.00,56.00)d | -6.810 | 0.000b |

| SF-36 total score | ||||

| Postoperative 3 mo | 393.57 ± 68.51 | 335.12 ± 83.11 | 3.389 | 0.001b |

| Postoperative 6 mo | 493.07 ± 69.97d | 363.64 ± 72.02d | 8.050 | 0.000b |

We performed a statistical analysis of the highest preoperative pain score and the pain score 24 h after surgery and found that the pain score improved significantly after surgery (P < 0.01) (Table 4).

| VA score | t | P value | |

| Highest preoperative pain | 6.51 (0.60) | 9.064 | < 0.01 |

| Postoperative pain score at 24 h | 5.48 (0.64) |

From the general data that we found (Table 5), the pain scores of the surgical group at each time point were lower than those of the conservative group. Analysis of variance showed that the difference in pain scores between the two groups was statistically significant (F = 363.017, P < 0.001), indicating that the effects of different treatments on pain scores were mixed.

| Time | Surgical group | Conservative group |

| The highest score of preoperative pain (the highest pain score within 72 h after injury) | 6.51 (0.60) | 6.31 (0.57) |

| Pain score at 72 h postoperatively (pain score 1wk after injury) | 3.95 (0.72)d | 5.46 (0.55)ad |

| Pain score at 2wk after surgery (2 wk pain score after injury) | 2.95 (0.39)d | 4.67 (0.53)ad |

| Pain score at 4wk after surgery (4 wk post-injury pain score) | 2.54 (0.51)d | 3.92 (0.48)ad |

| Pain score at 6wk after surgery (6 wk post-injury pain score) | 1.87 (0.34)d | 3.33 (0.48)ad |

| Pain score at 3 mo after surgery (pain score after 3 mo) | 0.90 (0.45)d | 2.92 (0.27)ad |

| Pain score at 6 mo postoperatively (pain score after 6 mo) | 0.36 (0.49)d | 2.05 (0.65)ad |

The differences in pain scores at different time points were statistically significant (F = 84.830, P < 0.001), indicating that the pain scores were different at each time point. Tests with within-subjects effects and tests with between-subjects effects showed significant interactions between different groups and at different time points (F = 53.733, P < 0.001).

There are currently no global guidelines or consensus on surgical indications for rib fractures. The surgical signs common in the current study are the following: (1) Selective patients with a flail chest[10]; (2) Patients with non-continuous thoracic fractures involving three or more double cortical fractures and displaced bones, although surgical treatment compared with nonsurgical treatment can improve the prognosis of patients (acute pain relief, reduction of pulmonary infection, hemothorax, empyema, respiratory failure, and tracheotomy)[11-13]; (3) Patients with rib fractures requiring mechanical ventilation, although internal fixation of rib fractures can shorten mechanical ventilation time and reduce patient mortality[14]; and (4) Severe pain that is difficult to control[15,16]. However, the definition of acute pain is rather vague, and there is no standard analgesic measure in clinical practice. The clinical manifestations of patients with rib fractures are quite different. Even if the imaging performance of rib fractures is relatively mild, the fractures can affect the stability of the thorax. Additionally, many patients may have severe respiratory distress due to a long-term smoking history or primary pulmonary diseases such as hypoxemia. We believe that these patients have the "clinical flail chest”. A large number of studies have shown the need for surgical treatment of patients with flail chest. We compared the prognosis of patients with severe non-flail chest rib fractures treated with surgical fixation and conservative treatment and explored the medical benefits of patients with severe rib fractures.

The "clinical flail chest” was used to emphasize the physiological changes caused by rib fractures. The surgery was used to allow a better recovery. The SF-36 scores in the operation group were better than those in the conservative group at 3 mo and 6 mo (P < 0.05), indicating that patients had excellent surgical treatment outcomes.

Pain is a clinically relevant observation index and serves as an evaluation index for our treatment effect. We compared the maximum preoperative pain score of the surgical group24 h after surgery and found that postoperative pain was significantly relieved (P < 0.01). Surgical treatment relieves acute pain in the affected areas of the patient. Surgeries for non-flail chest rib fractures were generally performed within 72 h after injury, so we compared the highest pain score before surgery with the highest pain score within 72 h after injury; the differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The fractures (72 h, 1 wk, 2 wk, 4 wk, 6 wk, 3 mo, and 6 mo after surgery) were significantly better in the surgery group than in the conservative group (P < 0.001). This shows that the surgical treatment of "clinical flail chest" is necessary to relieve pain and improve the quality of life of patients.

Some patients of our surgical treatment group were able to rise from the bed one day after surgery, and it can be seen from the SF-36 scores and pain scores that patients with severe non-continuous thoracic rib fractures recovered faster after surgery than patients with conservative treatment. The rapid relief of pain helps patients to cough and excrete sputum, recover quickly, and be more optimistic about treatment; these benefits reduce the incidence of some complications, such as prolonged bed rest caused by pressure ulcer, hypostatic pneumonia, and more severe infections, especially in older patients. Fast track surgery[17] has developed rapidly in recent years, and we believe that surgical treatment is also in line with the FTS requirements.

Some scholars have performed many studies on the surgical treatment of rib fractures; Qiu et al[18] performed a retrospective comparison of 124 cases of non-flail chest rib fractures, and they believe that patients with thoracic surgery have faster fracture healing, less pain, fewer lung infections, and better clinical results than patients without the surgery. Pieracci et al[13] believed that early surgical treatment of severe non-flail chest rib fractures can reduce the incidence of respiratory failure and intracranial hemorrhage in patients, which can improve the prognosis of patients. Moya et al[16], after evaluating the benefits of rib fracture surgery by the number of analgesic drugs, believe that the need for analgesic drugs after the operation is fixed in patients with multiple rib fractures and that severe pain is one of the surgical indications.

The limitations of this paper is its retrospective nature with a relative small number of patients, so multicenter studies with a large number of samples, long-term follow-up, and RCT design are needed to fully confirm this conclusion.

In summary, we believe that in clinical practice, we should pay more attention to the physiological function and clinical manifestations of patients with severe rib fractures. For patients with severe non-flail chest rib fractures, surgical treatment is effective. However, there are some factors, such as the high cost of surgery, the cost-to-benefit ratio, and the evaluation methods and fixation methods for severe non-flail chest rib fractures, that need to be considered. We need more prospective experiments in patients from multiple trauma centers and collaborative research to confirm our findings.

Rib fracture is caused by a large force impacting the chest wall and is a typical chest injury, accounting for 40%-80% of chest traumas. The severity of injury varies with the number of rib fractures, the presence or absence of angulation, and the age and physical condition of the patient; the injury may be accompanied by severe complications.

There are two types of treatments for rib fractures: Surgical treatment and conservative treatment. Surgical treatment involves rib fracture internal fixation in the literature, and this method is often reported in select patients with injuries to the flail chest. Conservative treatment includes analgesia and ventilator support. The clinical manifestations of patients with rib fractures vary widely.

Some patients who meet the diagnostic criteria for an image of flail chest have no abnormal breathing, have satisfactory pain management, and have mild respiratory complications. In contrast, many patients have inadequate long-term analgesia, respiratory distress, and hypoxemia due to a long-standing substantial smoking history or the presence of primary pulmonary diseases; analgesic treatment is not valid in these patients. Even if the imaging findings of rib fractures are relatively mild, rib fractures may cause severe position limitation, respiratory distress, and hypoxemia. Even further, mechanical ventilation may be needed, so the "clinical flail chest" condition should receive more attention.

Seventy-eight patients from our hospital with severe non-continuous thoracic rib fractures from September 2016 to September 2018 were enrolled in our study. Thirty-nine patients underwent surgical treatment, and 39 underwent conservative surgery. The surgical treatment group received surgery performed with titanium plates, and the screws were inserted with open reduction and internal fixation. The conservative treatment group received analgesia and symptomatic treatment. The pain scores at 72 h, 1 wk, 2 wk, 4 wk, 6 wk, 3 mo, and 6 mo were compared, and the SF-36 quality of life scores were compared at the 3rd and 6th months.

Pain relief in the surgical group was significantly better than that in the conservative group at each time point. The SF-36 scores were significantly higher in the conservative group than in the surgical group at1mo and 6 mo.

Patients with severe non-flail chest rib fractures have a better quality of life following surgical treatment than following conservative treatment, and surgical treatment is also useful for relieving pain.

We should pay more attention to the physiological functions and clinical manifestations of patients with severe rib fractures. In patients with non-flail chest rib fractures, surgical treatment is feasible and effective.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sharma RA, Yoon DH S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Lin FC, Li RY, Tung YW, Jeng KC, Tsai SC. Morbidity, mortality, associated injuries, and management of traumatic rib fractures. J Chin Med Assoc. 2016;79:329-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sirmali M, Türüt H, Topçu S, Gülhan E, Yazici U, Kaya S, Taştepe I. A comprehensive analysis of traumatic rib fractures: morbidity, mortality and management. Eur J CardiothoracSurg. 2003;24:133-138. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Fabricant L, Ham B, Mullins R, Mayberry J. Prolonged pain and disability are common after rib fractures. Am J Surg. 2013;205:511-5; discusssion 515-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dehghan N, de Mestral C, McKee MD, Schemitsch EH, Nathens A. Flail chest injuries: a review of outcomes and treatment practices from the National Trauma Data Bank. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:462-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bemelman M, Poeze M, Blokhuis TJ, Leenen LP. Historic overview of treatment techniques for rib fractures and flail chest. Eur J Trauma EmergSurg. 2010;36:407-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nirula R, Diaz JJ, Trunkey DD, Mayberry JC. Rib fracture repair: indications, technical issues, and future directions. World J Surg. 2009;33:14-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ho AM, Karmakar MK, Critchley LA. Acute pain management of patients with multiple fractured ribs: a focus on regional techniques. CurrOpinCritCare. 2011;17:323-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Karmakar MK, Ho AM. Acute pain management of patients with multiple fractured ribs. J Trauma. 2003;54:615-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tarlov AR, Ware JE, Greenfield S, Nelson EC, Perrin E, Zubkoff M. The Medical Outcomes Study.An application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. JAMA. 1989;262:925-930. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Bottlang M, Long WB, Phelan D, Fielder D, Madey SM. Surgical stabilization of flail chest injuries with MatrixRIB implants: a prospective observational study. Injury. 2013;44:232-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Majercik S, Vijayakumar S, Olsen G, Wilson E, Gardner S, Granger SR, Van Boerum DH, White TW. Surgical stabilization of severe rib fractures decreases incidence of retained hemothorax and empyema. Am J Surg. 2015;210:1112-6; discussion 1116-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mayberry J. Surgical stabilization of severe rib fractures: Several caveats. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pieracci FM, Lin Y, Rodil M, Synder M, Herbert B, Tran DK, Stoval RT, Johnson JL, Biffl WL, Barnett CC, Cothren-Burlew C, Fox C, Jurkovich GJ, Moore EE. A prospective, controlled clinical evaluation of surgical stabilization of severe rib fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80:187-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pieracci FM, Rodil M, Stovall RT, Johnson JL, Biffl WL, Mauffrey C, Moore EE, Jurkovich GJ. Surgical stabilization of severe rib fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:883-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Majercik S, Cannon Q, Granger SR, VanBoerum DH, White TW. Long-term patient outcomes after surgical stabilization of rib fractures. Am J Surg. 2014;208:88-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | de Moya M, Bramos T, Agarwal S, Fikry K, Janjua S, King DR, Alam HB, Velmahos GC, Burke P, Tobler W. Pain as an indication for rib fixation: a bi-institutional pilot study. J Trauma. 2011;71:1750-1754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Loop T. Fast track in thoracic surgery and anaesthesia: update of concepts. CurrOpinAnaesthesiol. 2016;29:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Qiu M, Shi Z, Xiao J, Zhang X, Ling S, Ling H. Potential Benefits of Rib Fracture Fixation in Patients with Flail Chest and Multiple Non-flail Rib Fractures. Indian J Surg. 2016;78:458-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |