Published online Nov 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i21.3595

Peer-review started: April 12, 2019

First decision: September 9, 2019

Revised: September 30, 2019

Accepted: October 15, 2019

Article in press: October 15, 2019

Published online: November 6, 2019

Processing time: 213 Days and 13.1 Hours

Necrotizing fasciitis is a severe bacterial skin infection that spreads quickly and is characterized by extensive necrosis of the deep and superficial fascia resulting in the devascularization and necrosis of associated tissues. Because of high morbidity and mortality, accurate diagnosis and early treatment with adequate antibiotics and surgical intervention are vital. And timely identification and treatment of complications are necessary to improve survival of patient.

We report a case of necrotizing fasciitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus in a patient using high doses of glucocorticoid and suffering from secondary diabetes mellitus. He was admitted to our hospital due to redness and oedema of the lower limbs. After admission, necrotizing fasciitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus was considered, and he was discharged after B-ultrasound drainage and multiple surgical operations. In the process of treatment, multiple organ functions were damaged, but with the help of multi-disciplinary treatment, the patient got better finally.

The key to successful management of necrotizing fasciitis is an early and accurate diagnosis. The method of using vacuum sealing drainage in postoperative patients can keep the wound dry and clean, reduce infection rate, and promote wound healing. Interdisciplinary collaboration is a vital prerequisite for successful treatment.

Core tip: Diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis is difficult due to absence of typical signs. Some imaging techniques involving computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and ultrasound could provide valuable morphological features for diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Our case highlights the importance of a combination of antibiotics, multiple surgical debridements, and multi-disciplinary treatment for the successful management of the patient with necrotizing fasciitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

- Citation: Xu LQ, Zhao XX, Wang PX, Yang J, Yang YM. Multidisciplinary treatment of a patient with necrotizing fasciitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(21): 3595-3602

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i21/3595.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i21.3595

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a severe soft tissue infection that spreads quickly and is characterized by extensive necrosis of the deep and superficial fascia resulting in the devascularization and necrosis of associated tissues. This rare condition has a high mortality rate and poses diagnostic and management challenges to the clinician. It can rapidly deteriorate into shock and sepsis, which may lead to multi-organ failure and an imminent life-threatening condition[1]. The high-risk conditions are diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, alcoholism, hypertension, chronic renal insufficiency, immunocompromised status, being elderly, malnourishment, and malignancy[2]. Typical/initial local clinical signs include erythema, extensive oedema, pain, discoloured wound drainage, vesicles or bullae, necrosis, and possibly crepitus. Systemic symptoms involve fever, toxic delirium, typical symptoms of septic shock (tachycardia, weak pulse, and hypotension), and eventually multi-organ failure. Because of high morbidity and mortality, accurate diagnosis and early treatment with adequate antibiotics and surgical intervention are vital[3]. Complex resuscitation and intensive care, including rehabilitation, are standard components of post-surgical management. This article describes the treatment and outcomes of one patient with NF, discusses the identification and treatment of complications, and explores interdisciplinary collaboration as a vital prerequisite for successful treatment.

A 61-year-old man presented with a 2-mo history of systemic erythema and one and a half- months history of oedema of the lower limbs.

He had been administered allopurinol tablets two months ago because of gout; unfortunately, he developed a systemic rash. The rash was scattered throughout the body, was granular with dark red papules, and was accompanied by scratches, partial ulceration, and scabs. He denied any cough, cold, fever, joint pain, diarrhea, or urinary symptoms. He initially sought care at an outside hospital, where his laboratory data showed an elevated white blood cell count (32.3 × 109/L, 91.6% neutrophils and 2.6% eosinophils), high C-reactive protein (CRP) (175 mg/L), and high ALT (133 U/L). He was diagnosed with drug-induced dermatitis and was given 60 mg glucocorticoid once a day (reduced by 8 mg every 5 d) and loratadine and cetirizine as antiallergic therapy. The rash disappeared and the patient was discharged. One and a half months ago, the patient presented with oedema of both lower limbs, particularly the right lower limb, associated with redness on the back of the foot, local tenderness, and higher skin temperatures (Figure 1). He came to our institution for help.

The patient had a 5-year history of hypertension and a 2-mo history of secondary diabetes associated with glucocorticoids.

The patient had no personal or family history.

At admission, his blood pressure was 129/86 mmHg, and his heart rate was 124 beats/min with a temperature of 38.7 °C. His respiration was 17 breaths per minute, and his saturation was 95% without oxygen. Physical examination revealed a localized red-purplish discoloration on both lower limbs. His chest was clear, and his abdomen was soft, with no guarding or rigidity.

His initial blood tests showed a white blood cell count of 13.2 × 109/L, neutrophilia at 93%, and hemoglobin (HGB) of 79 g/L. He had an elevated CRP level of 302 mg/L, elevated procalcitonin level of 2.84 ng/mL, degraded albumin level of 24 g/L, high serum creatinine (4.95 mg/dL), and elevated B-type natriuretic peptide (1791.6 pg/mL). His glycosylated haemoglobin was as high as 9.2%. Arterial blood-gas sampling indicated metabolic acidosis (pH: 7.32; base excess: -6.0 mEq/L). Blood electrolyte and liver function levels were normal. His chest radiography and other laboratory data, including amylase and cardiac enzyme levels, were unremarkable.

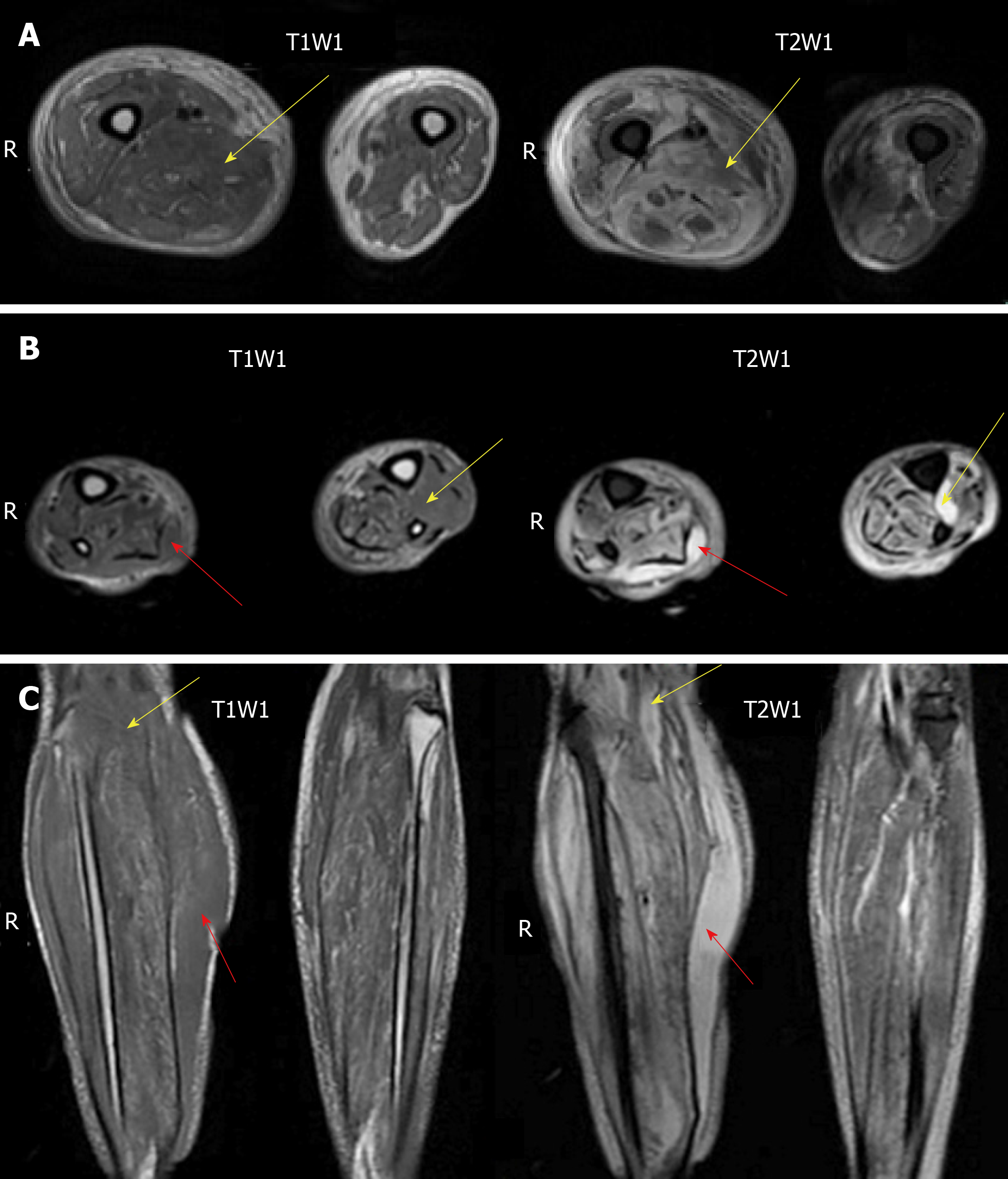

An ultrasonography scan showed oedema of the dorsum of the feet, and an intermuscular abscess of the right calf was suspected (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of both lower limbs revealed multiple muscle and subcutaneous soft tissue swelling, and intermuscular abscesses were observed (Figure 3).

Based on the clinical findings and the results of the pus and blood culture, the patient was finally diagnosed with NF caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

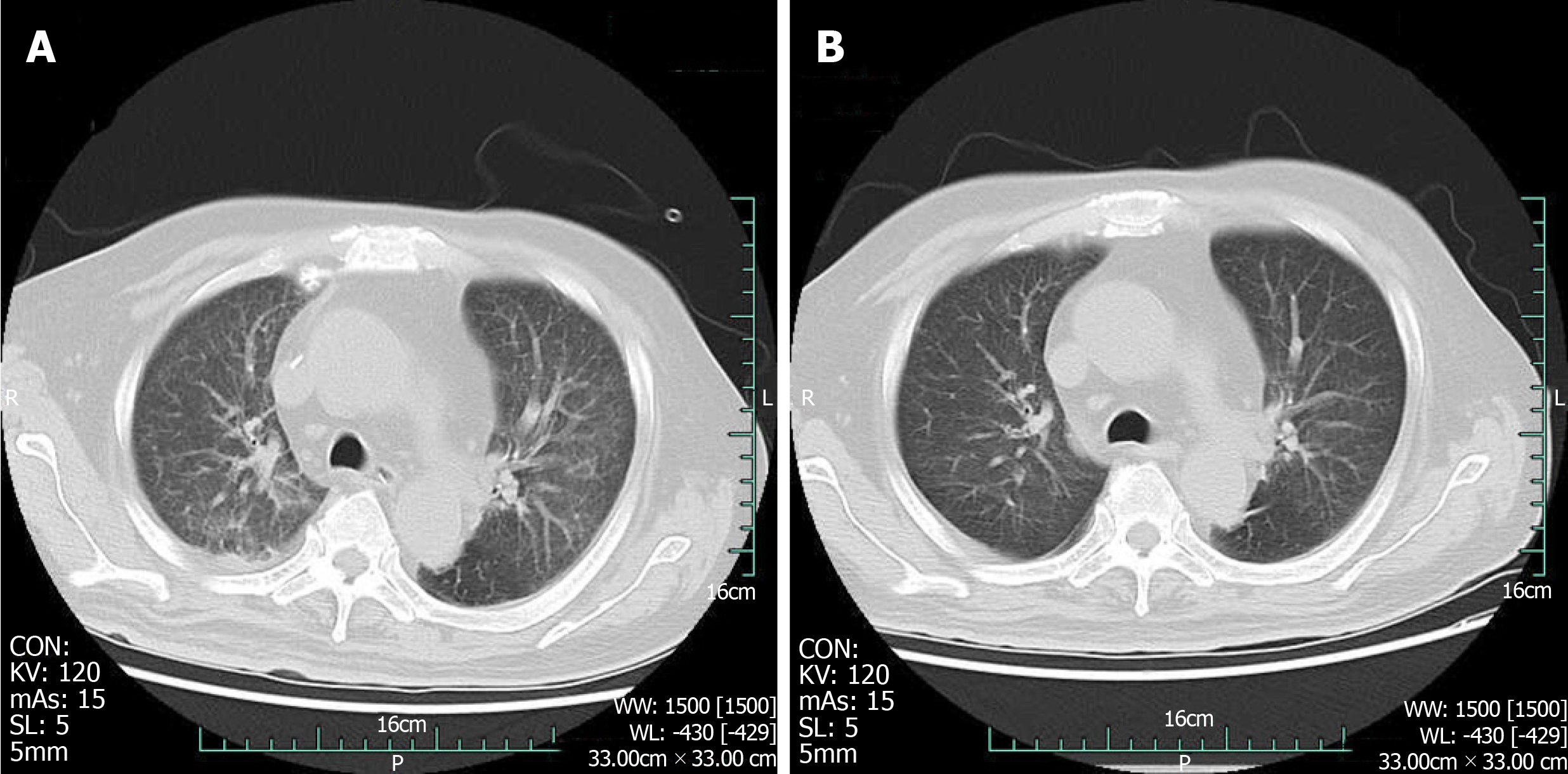

At admission, with a suspected diagnosis of soft tissue infection secondary to diabetes mellitus, the patient was started on broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics with cefoperazone sodium/sulbactam sodium (2 g every 8 h) and caspofungin (50 mg every day). He received serum albumin and fluids intravenously. Immunoglobulins were also administered. Blood glucose was monitored, and insulin was injected subcutaneously to control blood glucose levels. The target of blood glucose control was fasting levels of 5.0-7.0 mmol/L and no more than 11.0 mmol/L after meals. While all of these were being performed, an ultrasonography scan showed oedema of the dorsum of the feet, and an intermuscular abscess of the right calf was suspected (Figure 2). Thus, ultrasound-guided abscess puncture and drainage were performed the following day, and 105 mL of bloody purulent fluid was drained. On the second day after drainage, his temperature dropped to 37.4 °C, and laboratory data showed a degraded white blood cell count (10.5 × 109/L, with 88.9% neutrophils) and a CRP level of 128.50 mg/L. Gram staining of the purulent fluid showed the presence of Gram-positive cocci. A subsequent culture of the purulent fluid confirmed Staphylococcus aureus as the causative organism. Staphylococcus aureus was also detected in blood culture. The sputum culture was negative. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was not isolated from the culture. Intravenous injection of linezolid was given according to drug sensitivity. Unfortunately, on the following day, the patient presented with fever again, and the second ultrasound showed that the abscess was narrowed, but the drainage was not smooth, and a little purulent fluid was drained from the tube every day. An MRI scan of both lower limbs revealed multiple muscle and subcutaneous soft tissue swelling, and intermuscular abscesses were observed (Figure 3). He underwent surgical debridement of the necrotic tissue within 48 h of his arrival to our department. The necrotic tissue in the deep fascia was greyish during the operation (Figure 4), and the presence of purulent fluid confirmed the diagnosis. The culture of the necrotic tissues revealed Staphylococcus infection. Postoperatively, vacuum sealing drainage (VSD) was performed, the negative pressure was maintained between 40 and 60 kPa, and saline was given for continuous irrigation. One week later, the patient received the second debridement for the unhealed right leg. The sixth day after the seconded debridement, the patient suddenly coughed up 3 mL of bloody sputum before the third debridement. He was short of breath, and his saturation was 93% with an oxygen concentration of 33%. Remarkable wheezes in both lungs were heard on auscultation. Echocardiography showed slight enlargement of the left ventricular cavity with an ejection fraction of 57%, with a small amount of pericardial effusions. Blood tests showed moderate anaemia (67 g/L of HGB), elevated brain natriuretic peptide (>9000 ng/mL), and a slight elevation of lactate dehydrogenase. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed acute bilateral pulmonary oedema and a small amount of pleural effusions at the base of both lungs (Figure 5A). For the benefit of the patient, we organized multi-disciplinary treatment on time, including the infectious disease department, intensive care unit, cardiology department, respiratory department, and orthopaedics department. All the experts agreed that severe infection and toxin deposition damaged the myocardium, leading to decreased cardiac function and acute left heart failure. In terms of treatment, in addition to the antibacterial therapy mentioned above, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation was given to reduce left ventricular loading, combined with glucocorticoids to relieve toxaemia. Diuretics were used appropriately, and the amount of intravenous fluid input was in accordance with the amount of output, with a slow infusion rate. Immunoglobulin and thymosin were administered to boost the immune system of the patient. Red blood cells and erythropoietin (EPO) supplementation were intermittently infused because of anaemia. These aggressive therapeutic interventions gradually improved his general condition. After 1 wk of the abovementioned procedures, repeated CT scans showed bilateral pulmonary oedema and pleural fluid absorption (Figure 5B). By the time the patient's heart and lung function could tolerate surgery and anaesthesia, he received repeated debridement once a week, and a total of 6 debridements were performed.

Finally, skin grafting was performed on the dorsum of the right foot after several debridements. The patient was discharged 4 mo after hospitalization. We carried out regular follow-ups every 6 mo, which revealed that the patient remained alive with well-controlled diabetes.

The term “necrotizing fasciitis” has developed over the past few centuries. It was first described in soldiers during the American Civil War in the 18th century[1]. The term “necrotizing fasciitis” was first proposed by the American surgeon B. Wilson in 1952[4].

According to the microorganism involved, four types of NF are classified[5]. Type I is the most common type (70%-90%) and is a mixed infection caused by Gram-positive cocci (Streptococcus and Staphylococcus), Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella), and anaerobic bacteria such as Clostridium and Bacteroides[5,6]. Type II NF is generally monomicrobial, usually caused by group A Streptococcus alone or in combination with Staphylococcus aureus[7]. Type III describes a specific infection caused by marine Vibrio vulnificus[8]. Type IV is caused by a fungal infection, with the most common species being Candida spp. or zygomycetes[8,9].

The predisposing factors for NF are diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, alcoholism, hypertension, chronic renal insufficiency, malignant tumours, immunosuppressive therapy, and intramuscular injection of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs[10]. Among them, type 2 diabetes is the most common potential medical condition. Although this patient had no previous history of diabetes, he had high blood glucose and glycosylated haemoglobin at the time of admission and had a history of glucocorticoid therapy before admission. It was considered that he had secondary diabetes caused by glucocorticoids. Early symptoms of NF are not very typical; they are easy to ignore by clinicians. The early clinical signs of NF may include erythema, swelling, and local tenderness[11]. With the development of infection, the skin characteristically becomes more erythematous, with pain and swelling, and the boundary is blurred. The skin is purple-red and may become necrotic with bullae formation and eventually form haemorrhagic and gangrenous lesions. Large haemorrhagic bullae, skin necrosis, fluctuance, crepitus, sensory and motor impairment are the late symptoms of NF. It is essential to be alert to these symptoms because the earlier diagnosis of NF results in better outcomes and fewer complications[12]. Systemic clinical symptoms include fever, toxic delirium, typical signs of shock (tachycardia and hypotension), and eventually multi-organ dysfunction[13-15]. According to the current literature, the incidence of NF is relatively low, but the reported total mortality rate is as high as 20%[7]. The total cost of treatment during hospital stay was significantly high. NF develops frequently in the limbs, but also in the head and neck, trunk, perineum, and scrotum[16-19]. Fournier gangrene is a specific type of necrotizing infection that occurs on the skin and soft tissue of the perineum[20]. In our case, the infection site was typical, and pathogenic bacteria were cultured in the early stage, which played a significant role in the timely diagnosis of this disease. Early laboratory tests may be normal, but as the infection progresses, laboratory findings include anaemia, raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate, thrombocytopenia, bloody urine, elevated creatine kinase, hyperbilirubinemia, azotemia, decreased albumin, hyponatremia, hypocalcaemia, and metabolic acidosis. Clinical diagnosis is typically done by imaging, including plain X-rays and ultrasound; CT and MRI are helpful in diagnosing suspicious cases. X-rays may show evidence of air in the involved soft tissue[21]. Ultrasound scans may show an irregularly shaped hypoechoic area, subcutaneous thickening, and air due to focal fat necrosis and inflammation. Emphasis should be placed on its utilization to save time for the timely management of life-threatening necrotizing infections[22]. CT and MRI can help to detect asymmetric fascial thickening, soft tissue air, blurred fascial planes, inflammatory fat stranding, reactive lymphadenopathy, and the presence and extent of infection. Compared to X-rays and ultrasound, CT and MRI have higher sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of NF. Currently, MRI is considered to be the gold standard imaging technology because of its high soft tissue contrast[23]. Surgical exploration can also establish the diagnosis of NF. Early surgical exploration and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics (covering Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria) play an important role in successful treatment. However, the extent of debridement depends on the physical findings during the operation and not on the CT or MRI images. The excised tissue should be sent for Gram staining, culture, and histological examination. The necrotic tissue should be completely removed and fully drained, and no dead space should be allowed. If the necrotic area of fascia is enlarged, repeated operations are required. Wound closure is carefully planned because early closure carries the risk of residual infection and poor healing. After the bacterial culture and drug sensitivity results are obtained, sensitive antibiotics are administered. VSD is a wound management method that involves placing a closed dressing on a dedicated wound package and applying a vacuum on the dressing. It has been shown to promote wound healing, control wound drainage, and prevent infection. The significance of maintaining continuous negative pressure on the wound is to remove the metabolism products at the wound surface in a timely manner, keep the wound dry and clean, increase granulation, increase local blood perfusion, decrease hospital length of stay, and expedite final wound closure. At the same time, VSD allows the solution to dwell and then applies a negative pressure to remove the liquid along with any debris. It is especially useful for infectious wounds requiring frequent debridement[24]. Albumin can promote wound healing, while red blood cells and EPO supplementation can promote the proliferation of red blood cells. Intermittent infusion of plasma and immunoglobulins can improve the body’s non-specific immunity. Studies have shown that a large amount of immunoglobulins can improve the non-specific ability of the body’s immunity, which is important for the treatment of fasciitis. Immunoglobulin can increase the survival rate of septic shock caused by NF from 50% to 87%[25]. Thymosin α1 has a good immunoregulatory effect and can enhance the immune function of the body, assist the efficacy of antibacterial drugs, reduce infection complications, and improve prognosis. Patients with NF often suffer from the formation of microembolism. Extensive microembolism can occur at the lesion site and surrounding tissues, making it difficult for antibiotics to reach the lesion and causing occlusion of the fascial supply vessels. In addition, the patient was in bed for a long time, and his lower limbs were immobilized because of surgery, placing him at a high risk of venous thromboembolism; however, there is no contraindication for anticoagulation. Therefore, this patient received a subcutaneous injection of low molecular weight heparin as an anticoagulant therapy in the early stages.

The advantages of different disciplines were combined to improve the therapeutic effect for this patient. They included physicians who offered early basic life support and organ function maintenance, surgeons who performed surgical interventions, bacteriological experts who provided culture and drug sensitivity results on time, dietitians who provided effective nutrition support, and anaesthesiologists who conducted the perioperative management of the patient. In addition, the radiology department provided imaging data for clinical diagnosis and treatment analysis. Interdisciplinary intensive care was a necessary condition for the successful treatment of this patient.

NF, although not common, can cause notable rates of morbidity and mortality. Because of the lack of characteristic skin manifestations, it is important for physicians or surgeons to increase awareness of the early cutaneous findings in the course of the disease. Prompt diagnosis and early operative debridement with adequate antibiotics are vital. Interdisciplinary intensive care treatment is a guarantee for successful therapy.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lei BF S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Hakkarainen TW, Kopari NM, Pham TN, Evans HL. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: review and current concepts in treatment, systems of care, and outcomes. Curr Probl Surg. 2014;51:344-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang JM, Lim HK. Necrotizing fasciitis: eight-year experience and literature review. Braz J Infect Dis. 2014;18:137-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kapp DL, Rogers M, Hermans MHE. Necrotizing Fasciitis: An Overview and 2 Illustrative Cases. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2018;17:295-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Leiblein M, Marzi I, Sander AL, Barker JH, Ebert F, Frank J. Necrotizing fasciitis: treatment concepts and clinical results. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;44:279-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Khamnuan P, Chongruksut W, Jearwattanakanok K, Patumanond J, Yodluangfun S, Tantraworasin A. Necrotizing fasciitis: risk factors of mortality. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2015;8:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, Schwab CW. Necrotizing fasciitis: current concepts and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:279-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Neilly DW, Smith M, Woo A, Bateman V, Stevenson I. Necrotising fasciitis in the North East of Scotland: a 10-year retrospective review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2019;101:363-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Misiakos EP, Bagias G, Patapis P, Sotiropoulos D, Kanavidis P, Machairas A. Current concepts in the management of necrotizing fasciitis. Front Surg. 2014;1:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Das DK, Baker MG, Venugopal K. Risk factors, microbiological findings and outcomes of necrotizing fasciitis in New Zealand: a retrospective chart review. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bucca K, Spencer R, Orford N, Cattigan C, Athan E, McDonald A. Early diagnosis and treatment of necrotizing fasciitis can improve survival: an observational intensive care unit cohort study. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:365-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Livingstone JP, Hasegawa IG, Murray P. Utilizing Negative Pressure Wound Therapy with Instillation and Dwell Time for Extensive Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Lower Extremity: A Case Report. Cureus. 2018;10:e3483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Minini A, Galli S, Salvi AG, Zarattini G. Necrotizing fasciitis of the hand: a case report. Acta Biomed. 2018;90:162-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Frank J, Barker JH, Marzi I. Necrotizing Fasciitis of the Extremities. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2008;34:229-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Herr M, Grabein B, Palm HG, Efinger K, Riesner HJ, Friemert B, Willy C. [Necrotizing fasciitis. 2011 update]. Unfallchirurg. 2011;114:197-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ran C, Hicks K, Alexiev B, Patel AK, Patel UA, Matsuoka AJ. Cervicofacial necrotising fasciitis by clindamycin-resistant and methicillin-resistant <i>Staphylococcus aureus</i> (MRSA) in a young healthy man. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chiu HHC, Francisco CN, Bruno R, Jorge Ii M, Salvaña EM. Hypermucoviscous capsular 1 (K1) serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae necrotising fasciitis and metastatic endophthalmitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen SY, Fu JP, Wang CH, Lee TP, Chen SG. Fournier gangrene: a review of 41 patients and strategies for reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64:765-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wall DB, Klein SR, Black S, de Virgilio C. A simple model to help distinguish necrotizing fasciitis from nonnecrotizing soft tissue infection. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:227-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Castleberg E, Jenson N, Dinh VA. Diagnosis of necrotizing faciitis with bedside ultrasound: the STAFF Exam. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15:111-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tso DK, Singh AK. Necrotizing fasciitis of the lower extremity: imaging pearls and pitfalls. Br J Radiol. 2018;91:20180093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Miller Q, Bird E, Bird K, Meschter C, Moulton MJ. Effect of subatmospheric pressure on the acute healing wound. Curr Surg. 2004;61:205-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gupta S, Gabriel A, Lantis J, Téot L. Clinical recommendations and practical guide for negative pressure wound therapy with instillation. Int Wound J. 2016;13:159-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Linnér A, Darenberg J, Sjölin J, Henriques-Normark B, Norrby-Teglund A. Clinical efficacy of polyspecific intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in patients with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome: a comparative observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:851-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li L, Li D, Shen C, Li D, Cai J, Tuo X, Zhang L. [Application of vacuum sealing drainage in the treatment of severe necrotizing fasciitis in extremities of patients]. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi. 2015;31:98-101. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Humar D, Datta V, Bast DJ, Beall B, De Azavedo JC, Nizet V. Streptolysin S and necrotising infections produced by group G streptococcus. Lancet. 2002;359:124-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |