Published online Nov 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i21.3486

Peer-review started: April 24, 2019

First decision: June 28, 2019

Revised: July 5, 2019

Accepted: July 27, 2019

Article in press: July 27, 2019

Published online: November 6, 2019

Processing time: 198 Days and 2.6 Hours

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional constipation (FC) are two commonly encountered functional gastrointestinal disorders in clinical practice and are usually managed with Western medicines in cooperation with traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) interventions. Although clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) have been developed to assist clinicians with their decisions, there are still gaps in management with regard to integrative medicine (IM) recommendations.

To comprehensively review the currently available CPGs and to provide a reference for addressing the gaps in IBS and FC management.

We searched mainstream English and Chinese databases and collected data from January 1990 to January 2019. The search was additionally enriched by manual searches and the use of publicly available resources. Based on the development method, the guidelines were classified into evidence-based (EB) guidelines, consensus-based (CB) guidelines, and consensus-based guidelines with no comprehensive consideration of the EB (CB-EB) guidelines. With regard to the recommendations, the strength of the interventions was uniformly converted to a 4-point grading scale.

Thirty CPGs met the inclusion criteria and were captured as data extraction sources. Most Western medicine (WM) CPGs were developed as EB guidelines. All TCM CPGs and most IM CPGs were identified as CB guidelines. Only the 2011 IBS and IM CPG was a CB-EB set of guidelines. Antispasmodics and peppermint oil for pain, loperamide for diarrhea, and linaclotide for constipation were relatively common in the treatment of IBS. Psyllium bulking agents, polyethylene glycol and lactulose as osmotic laxatives, bisacodyl and sodium picosulfate as stimulant laxatives, lubiprostone and linaclotide as prosecretory agents, and prucalopride were strongly recommended or recommended in FC. TCM interventions were suggested based on pattern differentiation, while the recommendation level was considered to be weak or insufficient.

WM CPGs generally provide a comprehensive management algorithm, although there are still some gaps that could be addressed with TCM. Specific high-quality trials are needed to enrich the evidence.

Core tip: Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional constipation (FC) are two commonly encountered functional intestinal disorders. Current Western medicine clinical practice guidelines provide relatively complete management algorithms, while there are still gaps that could be filled by traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), such as global symptom alleviation of IBS, interval interventions in FC, and special population solutions. TCM interventions are based on a different medical system and on weak recommendations at present. Future emphasis should be placed on high-quality clinical trial design and implementation to enrich the TCM evidence.

- Citation: Dai L, Zhong LL, Ji G. Irritable bowel syndrome and functional constipation management with integrative medicine: A systematic review. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(21): 3486-3504

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i21/3486.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i21.3486

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional constipation (FC) are two functional intestinal diseases frequently encountered in clinical practice. Based on the recent epidemiological investigations in Asia, the prevalence rates of IBS and FC were 45.1% and 14.7%, respectively, among functional gastrointestinal disorder patients in hospital-based outpatient clinics[1]. In South China, the prevalence rates of IBS and FC were reported to be approximately 12% and 24%, respectively, among patients with functional bowel disorders[2]. Although there is a large population base, the pathophysiologies of IBS and FC are still not clear, and consequently, conventional interventions only focus on improving symptoms. However, the unsatisfactory response to chemical agents and the high economic burden of the new drugs still trouble patients and clinical practitioners[3-6]. Hence, many doctors and patients should consider introducing complementary and alternative medicine in their disease management strategies; traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is one of the major medical systems in China.

Both ancient classics and modern studies have illustrated the safety and efficacy of TCM therapies for IBS and FC[7-12]. As a result, TCM is frequently utilized in combination with Western medicine (WM) in IBS and FC management, which generates a new concept called integrative medicine (IM). However, TCM is a complicated and individualized medical system based on unique diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms, namely, pattern differentiation[13]. In addition, multiple intervention methods, such as herbal medicine, acupuncture, moxibustion, and other external therapies, are also involved. There is still debate about when to combine methods and which method or methods should be combined in IM.

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), which are systematically developed statements, are compulsory tools for clinical practitioners, and they provide accurate and appropriate suggestions for the appropriate course of action in specific clinical circumstances[14]. The aim of CPGs is to enhance the quality of health care by translating new research findings into clinical practice[15]. For clinical challenges such as IBS and FC, there are continuous updates to the guidelines to assist clinical doctors in both WM and TCM. Consequently, the best method of implementing these guidelines into practice effectively becomes a significant issue. Therefore, we systematically reviewed the currently available CPGs and identified those based on strong evidence to provide comprehensive suggestions to clinicians. Moreover, in consideration of the Chinese medical system, we also summarized the clinical questions that have the potential to be addressed by IM.

We comprehensively searched PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, the Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (SinoMed), the Chinese Scientific Journal Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Wanfang and collected data from January 1990 to January 2019. The following search terms and corresponding synonyms were applied: “clinical practice guideline”, “medical statement”, “expert consensus”, “irritable bowel syndrome”, and “functional constipation”. The detailed search strategy is shown in Supplement Figure 1. To enrich the data, we also browsed webpages of national public health departments and mainstream professional academic organizations, including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO), and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG). In addition, a manual search of handbooks in China was also performed to enrich the data source.

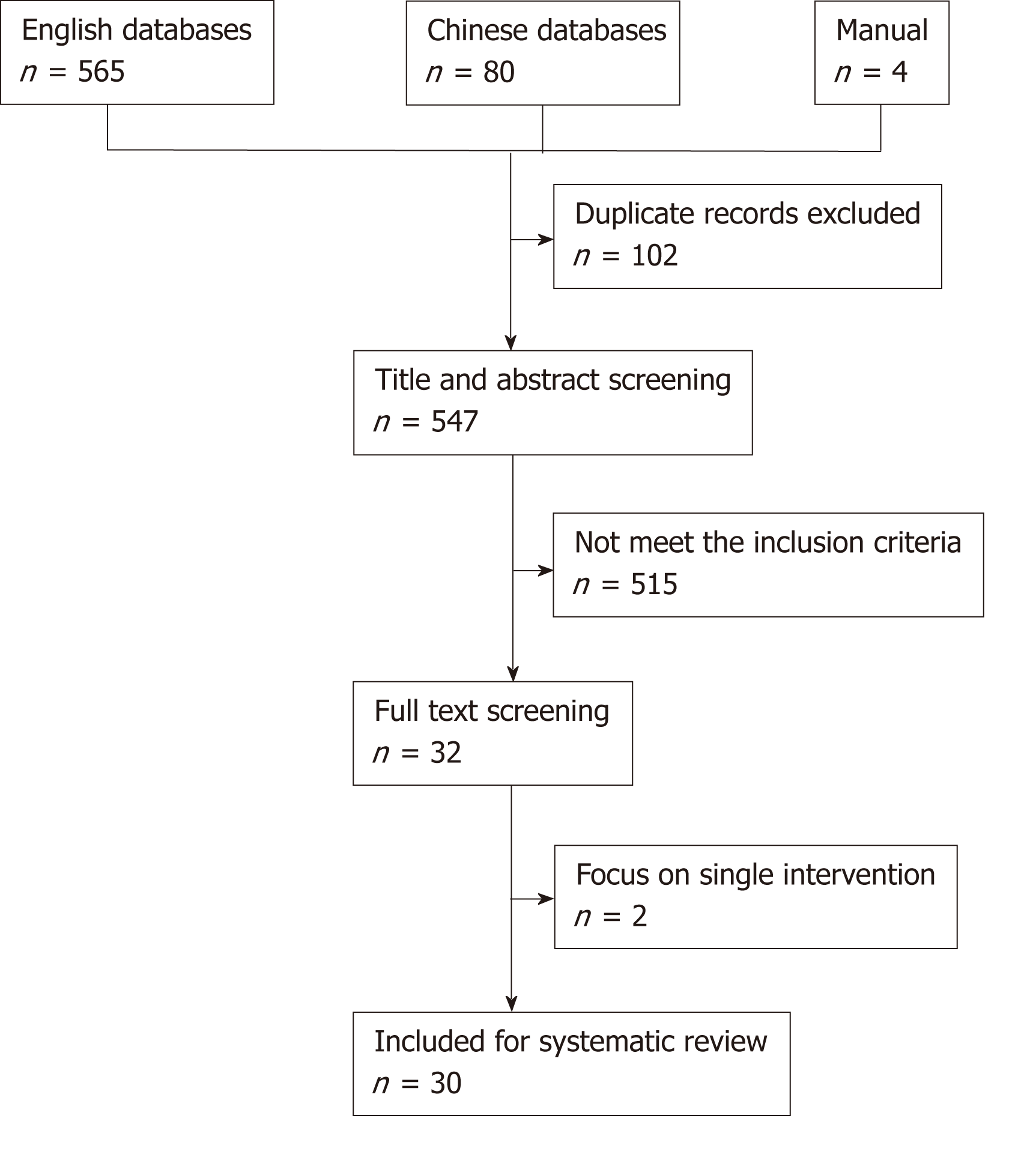

The inclusion criteria for the guidelines were as follows: (1) The title included the terms “irritable bowel disease/IBS/FC/chronic constipation/primary constipation/idiopathic constipation” and “guideline/medical statement/ consensus/monograph”; (2) The guidelines were developed by national authorities, international academic associations, or professional administration organizations; (3) The target patients were the general adult population; and (4) The guideline was published in English or Chinese. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) The guidelines were only focused on elderly patients; and (2) The guidelines only involved a single specific intervention. The process of guideline selection is presented in Figure 1.

Two authors independently conducted the literature search, CPG selection, and data extraction. The extracted information contained the initiating organization, title, year of publication, definition of disease, and recommendation details. Disagreement was resolved by discussion, and consensus was reached with a third individual (GJ).

Evidence-based (EB) guidelines, consensus-based (CB) guidelines, and consensus-based with no comprehensive consideration of EB (CB-EB) guidelines were distinguished on the basis of the development method[16]. An EB guideline was defined as a guideline developed after comprehensively reviewing and appraising the available literature, while a CB guideline is a guideline generated based on the consolidated opinions of a group of specialists. A CB-EB guideline is a special type of guideline developed based on a combination of expert consensus and some degree of explicit evidence appraisal[16].

For the purpose of normalizing the recommendations, the strength of the recommendations concerning the interventions were converted into a 4-level scoring system: (1) Strongly recommended; (2) Recommended; (3) Weak evidence; and (4) Insufficient evidence[17]. The highest level ‘‘strongly recommended’’ was based on at least one high-quality systematic review/meta-analysis or randomized controlled trial (RCT), with a strong body of evidence supporting the recommendation. The second highest level, “recommended,” was based on at least one controlled clinical trial or RCT of lower quality, with a good body of evidence that could be convincing in clinical practice. “Weak evidence’’ is supported only by a strong clinical or expert opinion but lacks a basis in scientific evidence, and it should be utilized with caution. The lowest level is “insufficient evidence”, which means that the statement is lacking in scientific evidence, and the subject of controversy is not supported by clinical or expert consensus.

Two authors individually assessed the levels of the recommendations. Disagreement was resolved by discussion, and consensus was reached with a third individual (GJ).

Given that this systematic review was based on CPG, no statistical analyses were conducted.

A total of 649 records were captured, of which 30 CPGs met the inclusion criteria and were chosen as the data sources (16 IBS CPGs, 10 FC CPGs, and 4 CPGs for both)[18-48]. The general information regarding these CPGs is summarized in Table 1. All CPGs were developed with the support of professional academic associations, except for two IBS CPGs, namely, the IBS NICE guideline[27], which was generated by a special guideline development group from the Royal College of Nursing, and the IBS Hong Kong guideline[31], which was developed by a special committee composed of ten clinical doctors.

| Disease | No. | Title | Publication year | Academic organization | Category | Medical system |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 1 | American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: Irritable bowel syndrome | 2002 | American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) | EB | WM |

| 2 | Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management | 2007 | British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) | EB | WM | |

| 3 | Asian consensus on irritable bowel syndrome | 2010 | Asian Neurogastroenterology and Motility Association (ANMA) | EB | WM | |

| 4 | Diagnosis and treatment consensus on irritable bowel syndrome with traditional Chinese medicine | 2010 | China Society of Digestive Diseases in Chinese Medicine | CB | TCM | |

| 5 | Irritable bowel syndrome--the main recommendations | 2011 | German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) German Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility (DGNM) | EB | WM | |

| 6 | Consensus on irritable bowel syndrome by integrative medicine | 2011 | Speciality Committee of Digestive Diseases, Chinese Association of Integrative Medicine (CAIM) | CB-EB | IM | |

| 7 | American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome | 2014 | American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) | EB | WM | |

| 8 | Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for irritable bowel syndrome | 2015 | Japanese Society of Gastroenterology (JSGE) | EB | WM | |

| 9 | Irritable bowel syndrome: a global perspective | 2015 | World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO) | CB-EB | WM | |

| 10 | Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management | 2015 | National Collaborating Centre for Nursing and Supportive Care (NICE) | CB-EB | WM | |

| 11 | Expert consensus on irritable bowel syndrome in China | 2016 | Chinese Society of Gastroenterology (CSGE) | EB | WM | |

| 12 | Danish national guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of irritable bowel syndrome | 2017 | Danish Society for Gastroenterology and Hepatology (DSGH) | EB | WM | |

| 13 | Diagnosis and treatment consensus on irritable bowel syndrome with traditional Chinese medicine (2017) | 2017 | China Society of Digestive Diseases in Chinese Medicine | CB | TCM | |

| 14 | The current treatment landscape of irritable bowel syndrome in adults in Hong Kong: Consensus statements | 2017 | Multidisciplinary group of clinicians | CB-EB | WM | |

| 15 | Diagnosis and treatment consensus on irritable bowel syndrome with integrative medicine (2017) | 2017 | Speciality Committee of Digestive Diseases, Chinese Association of Integrative Medicine (CAIM) | CB | IM | |

| 16 | Clinical practice guidelines for irritable bowel syndrome in Korea, 2017 revised edition | 2018 | Korean Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (KSNM) | EB | WM | |

| Functional constipation | 1 | Diagnosis and treatment consensus on functional constipation with traditional Chinese medicine | 2011 | China Society of Digestive Diseases in Chinese Medicine | CB | TCM |

| 2 | World Gastroenterology Organisation global guideline constipation - a global perspective | 2011 | World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO) | CB-EB | WM | |

| 3 | Consensus statement AIGO/SICCR: Diagnosis and treatment of chronic constipation and obstructed defecation | 2012 | Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists (AIGO), Italian Society of Colo-Rectal Surgery (SICCR) | EB | WM | |

| 4 | American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation | 2013 | American Gastroenterological Association medical (AGA) | EB | WM | |

| 5 | Diagnosis and treatment guideline of chronic constipation in China | 2013 | Gastrointestinal Motility Group of Digestive Disease Branch and Colorecatal Group of Surgery Branch of Chinese Medical Association | CB-EB | WM | |

| 6 | Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic functional constipation in Korea, 2015 revised edition | 2016 | Korean Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (KSNM) | EB | WM | |

| 7 | Diagnosis and treatment expert consensus on chronic constipation with traditional Chinese medicine (2017) | 2017 | China Association of Chinese Medicine (CACM) | CB | TCM | |

| 8 | Diagnosis and treatment consensus on chronic constipation with integrative medicine | 2018 | Chinese Association of Integrative Medicine (CAIM) | CB | IM | |

| 9 | Clinical practice guidelines from the French National Society of Coloproctology in treating chronic constipation | 2018 | French National Society of Coloproctology (SNFCP) | EB | WM | |

| 10 | Indian consensus on chronic constipation in adults: A joint position statement of the Indian Motility and Functional Diseases Association and the Indian Society of Gastroenterology | 2018 | Indian Motility and Functional Diseases Association, Indian Society of Gastroenterology | EB | WM | |

| Both | 1 | Recommendations on chronic constipation (including constipation associated with irritable bowel syndrome) treatment | 2007 | Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) | EB | WM |

| 2 | Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of common internal diseases in Chinese medicine: Diseases of modern medicine | 2008 | China Association of Chinese Medicine (CACM) | CB | TCM | |

| 3 | American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation | 2014 | American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) | EB | WM | |

| 4 | Clinical practice guideline: Irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and functional constipation in the adult | 2016 | Sociedad Española de Patología Digestiva (SEPD), Sociedad Española de Medicina de Familia y Comunitaria (semFYC), Sociedad Española de Médicos de Atención Primaria (SEMERGEN) and Sociedad Española de Médicos Generales y de Familia (SEMG) | EB | WM |

For IBS, essentially all WM CPGs were EB guidelines except for three (WGO guideline, NICE guideline, and Hong Kong guideline), which were developed as CB-EB guidelines[26,27,31]. The two TCM guidelines were CB guidelines[21,30]. Two IM guidelines were identified: the earlier 2011 IM CPG was a CB-EB guideline[23], while the latter 2017 IM CPG was a CB guideline[32]. Among the 16 CPGs, one CPG only contained pharmacological management recommendations[24], and the rest were comprehensive IBS guidelines. For FC, two WM CPGs were developed as CB-EB guidelines[35,38], while the others were all EB guidelines. The remaining two TCM CPGs and one IM CPG were generated as CB guidelines[34,41,42]. One CPG focused only on treatment[43], and the remaining FC CPGs were comprehensive guidelines. Four guidelines pertained to both diseases, while one CPG only discussed the symptom of constipation, namely, IBS-constipation (IBS-C), and FC[45].

Based on the CPGs, the specific mechanisms underlying IBS remain unclear. Although no unique or characteristic pathophysiological mechanism has been identified for IBS, there are multiple interrelated factors that affect symptoms in individuals that are mentioned in the CPGs. Visceral hypersensitivity is the most convincing factor with strong evidence described in the guidelines. It is considered to be the core pathological mechanism underlying symptom occurrence and IBS development[18-20,22,26,28]. Another important factor was thought to be altered gut motility. However, the CPGs mentioned that the difference in gut motility between IBS patients and healthy individuals is quantitative rather than qualitative, which means that the altered motility may not always be related to the symptoms[18-20,22,28]. Other relevant factors include brain-gut axis dysregulation, microbiota abnormality, intestinal infection, mucosal inflammation, psychological disturbances, and genetics[18-20,22,25,28]. All these changes have been illustrated in IBS patients; however, whether they are causal or secondary alterations remains unclear.

Similarly, according to the CPGs with relevant content, the pathophysiology of FC is still unclear. Basically, FC is caused by changes in colonic motility and disorders of the pelvic floor and/or anorectal function[34,38,39,48]. Based on the current understanding, FC can be categorized into three subtypes: Slow transit constipation (STC), normal transit constipation (NTC), and defecatory disorder (DD)[34,38,39,48]. In addition, some guidelines mentioned that some patients may have combination subtypes or even present with characteristics of IBS[39,45,47,48].

For the diagnosis, the ROME criteria are the gold standard generally accepted by the CPGs. However, exceptions could be found in several guidelines. Specifically, the IBS NICE guideline used diagnostic criteria based on symptoms[27]. The 2016 Korean FC guideline provided a symptomatic definition of chronic constipation, including infrequent bowel movements, hard stool, sensation of incomplete evacuation, straining while defecating, sensation of anorectal blockage during defecation, and assistance of digital maneuvers[40]. In the 2018 French FC guideline, diagnostic information was not included[43]. Because the ROME criteria were updated over time, the diagnostic criteria given by the CPGs also continued to evolve. The ROME IV criteria were widely utilized in guidelines developed after 2016.

The description is relatively simple for the general management of IBS based on the available guidelines. Forming an effective therapeutic patient-doctor relationship was strongly recommended or recommended by six comprehensive CPGs[18,20,25-28,32], while other CPGs lacked relevant content. Symptom monitoring may be helpful to identify possible triggers that exacerbate symptoms, but symptom monitoring was only supported by weak evidence in two CPGs[18,20]. Ten CPGs with relevant content all found weak or insufficient evidence with regard to recommending dietary modification[18-20,25-28,45,47,48]. However, with regard to specific dietary interventions, the suggestions may not be consistent. A low fermentable oligo-di-monosaccharide and polyol (FODMAP) diet was the center of the debate. It was recommended by two CPGs[25,29], while the other six CPGs considered the evidence to be weak[28,31-33,47,48].

Three major symptoms of IBS are abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation. Therefore, the conventional pharmacological interventions were classified based on those three dimensions. A summary of the strengths of the recommendations is provided in Table 2.

| Drugs | Recommendations by CPGs | |

| Pain | Antispasmodics | Strongly recommended or recommended by 13 CPGs; weak evidence reported by 1 CPG |

| Peppermint oil | Strongly recommended or recommended by 4 CPGs | |

| TCAs1 | Strongly recommended or recommended by 10 CPGs; weak evidence reported by 3 CPG | |

| SSRIs | Strongly recommended or recommended by 10 CPGs; weak evidence reported by 3 CPG | |

| Diarrhea | Loperamide | Recommended by 9 CPGs; weak evidence reported by 3 CPG |

| Alosetron2 | Strongly recommended or recommended by 7 CPGs | |

| Eluxadoline | Strongly recommended by 1 CPG; insufficient evidence reported by 1 CPG | |

| Constipation | Mosapride | Recommended by 1 CPG |

| Prucalopride | Insufficient evidence reported by 5 CPGs | |

| PEG | Recommended by 6 CPGs; weak evidence reported by 1 CPG; insufficient evidence reported by 7 CPGs3 | |

| Linaclotide | Strongly recommended or recommended by 7 CPGs | |

| Lubiprostone | Strongly recommended by 6 CPGs; insufficient evidence reported by 1 CPG | |

| Global symptoms | Probiotics | Strongly recommended or recommended by 6 CPGs; weak or insufficient evidence reported by 5 CPG |

| Rifaximin | Recommended by 6 CPGs; weak or insufficient evidence reported by 5 CPG |

Antispasmodics were the main drugs used to address pain in IBS. They were strongly recommended or recommended by 13 CPGs[18-20,22,24-29,31,33,48], while only 1 CPG reported weak evidence[47]. Peppermint oil was the other drug that had the potential to be considered a first-line therapy for pain. Three CPGs strongly recommended or recommended it[26,29,47,48]. Antidepressants, including tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), could be considered when the first-line therapies were ineffective. Ten CPGs strongly recommended or recommended the application of antidepressants for severe pain[18-20,22,25,28,29,33,47,48], while three CPGs reported weak evidence[24,26,27]. Interestingly, several CPGs suggested that TCAs should be avoided in IBS-C patients because of adverse events[20,47,48].

Currently, only three antidiarrheals have been applied in clinical practice: loperamide, alosetron, and eluxadoline. Loperamide was recommended by nine CPGs[18-20,22,24-26,28,47], while three CPGs reported weak evidence[27,29,33]. However, many guidelines suggested that loperamide could only be used to relieve the symptoms of diarrhea but not to improve IBS global symptoms[20,24-26,28,29,33,47]. Alosetron is a type of 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist and can only be used in women with severe IBS-D. It was strongly recommended by three CPGs [19,22,25] and recommended by four other CPGs[24,26,28,47]. Eluxadoline is a new agent approved in the United States in 2015. Therefore, the 2015 WGO guideline reported insufficient evidence[26], while the 2016 CSG guideline reported strong evidence[28].

5-HT4 receptor agonists, osmotic laxatives, and prosecretory agents are used for IBS-C. Mosapride and prucalopride are two available 5-HT4 receptor agonists. However, only one CPG recommended mosapride for IBS-C[25], and three CPGs reported insufficient evidence for prucalopride[22,25,29,33,48]. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is a type of osmotic laxatives available for IBS treatment. When considered for the relief of constipation, six CPGs recommended PEG[22,24,28,33,47,48], while the Danish guideline reported weak evidence[29]. However, when considered for the overall symptoms, seven CPGs reported insufficient evidence[24,25,28,33,45,47,48]. The prosecretory agents included lubiprostone and linaclotide. Linaclotide was strongly recommended or recommended by seven CPGs[24-26,28,29,47,48]. However, lubiprostone did not obtain consistent recommendations. Six CPGs gave strong recommendation[24-26,28,47,48], while the Korean guideline reported insufficient evidence[33].

Probiotics are also a type of drugs used for the treatment of IBS, and they are utilized to relieve the global symptoms of IBS. However, in general, the recommendation levels in the CPGs are not consistent. Six CPGs gave strong recommendation or recommendation[19,20,22,25,28,31], while the other five CPGs reported weak or insufficient evidence[26,29,33,47,48]. Additionally, some CPGs mentioned that the most effective species and strains were not yet confirmed[19,20,25,26,28,29,31,33,47]. Rifaximin is a synthetic antibiotic that could be considered for the treatment of IBS. It was recommended by six CPGs[19,24,26,28,31,47], while weak or insufficient evidence was reported by five CPGs[22,25,29,33,48].

The general management of FC includes appropriate physical exercise, increasing fluid intake and dietary fiber, and forming regular defecation habits. Among the nine CPGs that mentioned physical exercise, six gave weak recommendation[38,40-42,44,48], and three considered there to be insufficient evidence[37,43,45]. In addition, of the nine guidelines that referred to increased fluid intake, five provided weak recommendation[35,38,41,42,44], and the other four reported insufficient evidence[37,43,45,48]. With regard to increasing dietary fiber, two guidelines recommended that consuming food with a high soluble fiber content could benefit mild constipation[43,48]. The other six guidelines thought that there was only weak evidence supporting the recommendation of increasing dietary fiber intake[35,38-42,44,45,47]. Five guidelines mentioned the formation of defecation habits, with weak recommendation in the French guideline and three Chinese guidelines [38,41-43], while the 2012 Italian guideline reported insufficient evidence[37].

Although constipation is a symptom shared by IBS and FC, narration is more common in FC CPGs. The treatment of FC has a clear algorithm. Hence, the following elaboration was based on the therapeutic sequence. Table 3 summarizes the strengths of the recommendations in the corresponding guidelines.

| Category | Drugs | Recommendations by CPGs |

| Bulking agents | Psyllium | Strongly recommended or recommended by 10 CPGs |

| Bran | Recommended by 2 CPGs, insufficient evidence reported by 6 CPGs | |

| Stool softeners | Docusate sodium | Insufficient evidence reported by 4 CPGs |

| Liquid paraffin | Insufficient evidence reported by 4 CPGs | |

| Glycerin | Insufficient evidence reported by 4 CPGs | |

| Osmotic laxatives | PEG | Strongly recommended or recommended by 10 CPGs |

| Lactulose | Recommended by 10 CPGs | |

| Magnesium salts | Recommended by 1 CPG, insufficient evidence reported by 2 CPGs | |

| Stimulant laxatives | Bisacodyl | Recommended by 9 CPGs, weak evidence reported by 1 CPG, insufficient evidence reported by 1 CPG |

| Sodium picosulfate | Recommended by 9 CPGs, weak evidence reported by 1 CPG, insufficient evidence reported by 1 CPG | |

| Senna | Insufficient evidence reported by 6 CPGs | |

| Prosecretory agents | Lubiprostone | Strongly recommended or recommended by 7 CPGs |

| Linaclotide | Strongly recommended or recommended by 7 CPGs | |

| Others | Prucalopride | Strongly recommended or recommended by 9 CPGs |

| Probiotics | Insufficient evidence reported by 6 CPGs | |

| Enema and suppositories | Weak evidence reported by 6 CPGs, Strongly recommended by 1 CPG (CO2-releasing suppositories for distal constipation) |

Bulking agents are fiber supplements that can be classified into soluble fiber and insoluble fiber. Psyllium is the most frequently utilized soluble fiber supplement. It was strongly recommended or recommended by ten guidelines[35,37-40,42-45,47]. Bran is the representative insoluble fiber supplement. However, six CPGs reported insufficient evidence supporting the application of this fiber supplementation in clinical practice[35,37-39,44,47], and only two CPGs recommended it[42,43]. Stool softeners, such as docusate sodium, liquid paraffin, and glycerin, are not commonly used in clinical practice. Only four guidelines had relevant content, and they all considered there to be insufficient evidence supporting the usage of stool softeners[35,37,40,43].

Osmotic agents contain non-absorbable ions or molecules which retain water in the bowel lumen. The conventional medicines include polyethylene glycol (PEG), lactulose, and magnesium salts. Among these three agents, PEG was uniformly strongly recommended by all WM CPGs[35,37-40,43-45,47,48]. In addition, the only IM CPG also recommended the use of PEG. After PEG, lactulose was the next most commonly recommended, and it was uniformly recommended by nine WM CPGs and one IM CPG[35,37-39,42-45,47,48]. Only three CPGs mentioned magnesium salts, two of which reported insufficient evidence[37,45], while the French guideline recommended it based on updated evidence[43].

Stimulant laxatives promote fluid and electrolyte secretion by the colon or induce peristalsis in the colon. The commonly used agents contain bisacodyl, sodium picosulfate, and senna. Bisacodyl and sodium picosulfate were recommended by nine CPGs[35,37-40,42,44,47,48]; however, the French guideline only found weak evidence[43], and the 2007 Canadian guideline reported insufficient evidence[45]. In consideration of the publication years of these guidelines, the discrepancy in recommendations may be the result of updated evidence. In addition, as a conventional laxative, senna was not recommended in the clinical setting due to insufficient evidence[35,37-39,42,45]. However, although the efficacy of bisacodyl and sodium picosulfate was accepted by many CPGs, as stimulant laxatives, they can only be used in short term and then discontinued.

The currently available proseretory drugs are linaclotide and lubiprostone. Linaclotide is a guanylate cyclase C agonist which enhances intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) levels in the enterocyte and then promotes the secretion of bicarbonate and chloride into the lumen. Seven CPGs with related content strongly recommended it for the treatment of constipation[35,37-40,47,48]. Lubiprostone is a chloride channel activator that can enhance chloride secretion, improve transit, and facilitate defecation. Lubiprostone is also strongly recommended or recommended by seven CPGs[35,37-40,47,48].

Serotonin (5-HT) is a critical component in the gastrointestinal tract and could regulate gut motility, secretory and sensory functions. There are seven major classes of 5-HT receptor subtypes (5-HT1-7), and the stimulation of the 5-HT4 receptor is responsible for excitatory effects. Prucalopride is a selective 5-HT4 receptor agonist used in clinical practice and was strongly recommended or recommended by nine CPGs[35,37-40,42,44,47,48]. Probiotics are live bacteria and are thought to possess multiple immunoregulatory functions. Although probiotics are increasing popular in the management of functional gastrointestinal disorders, there is insufficient evidence to support their application in FC[37,40,43,45,47,48]. Enemas and suppositories are local treatments for constipation and have been utilized for hundreds of years. Although there is not enough scientific evidence to support their usage, six CPGs gave weak recommendation based on the expert consensus[38-40,43,45,48]. Nevertheless, the French guideline strongly recommended the use of a new type of CO2-releasing suppositories for distal constipation[43].

Biofeedback is a re-training technique based on the use of electrical or mechanical instruments to enhance the biological response. It can be used to train patients to relax their pelvic floor muscles while straining and to coordinate relaxation and pushing to achieve defecation. The efficacy and safety of biofeedback therapy have been demonstrated repeatedly in DD patients in multiple trials. Therefore, nine CPGs provided strong recommendation regarding biofeedback therapy for DD management[35,37-40,43-45,48].

For patients with severe STC and the failure to respond to conventional drugs, surgical treatment could be considered. This recommendation was made in seven guidelines. However, because of insufficient evidence, the evidence could only be considered weak[35,37-40,43-45,48]. In addition, the indications and surgical procedures should be comprehensively evaluated. Moreover, careful physical and laboratory tests are mandatory before surgical intervention.

In both diseases, there were five CPGs that gave recommendations regarding TCM interventions. However, due to limited evidence, TCM interventions were considered to have weak or insufficient evidence. Nevertheless, as mentioned above, TCM is widely utilized in clinical practice in China and East Asia. Therefore, we believe that it is still necessary to summarize the current TCM interventions, which could benefit their clinical applicability and future research.

Pattern differentiation is the core principle in TCM. Tables 4 and 5 summarize the patterns listed in the available TCM and IM guidelines for IBS and FC. The diagnosis of these patterns is based on patient symptoms along with inspection of the tongue and pulse. In general, patients should manifest at least two symptoms related to defecation and abdominal discomfort and at least two other somatic symptoms. The tongue and pulse inspections are for reference purposes. For IBS-diarrhea (IBS-D), “liver depression and spleen deficiency” was the commonly accepted pattern. For IBS-constipation (IBS-C), “liver depression and qi stagnation” was the generally agreed on pattern. For IBS-mixed (IBS-M), there was only one pattern listed, namely, “cold-heat complex”. For FC, four patterns were generally accepted: Intestinal excess heat, intestinal qi stagnation, dual deficiency of the lung and spleen, and spleen-kidney yang deficiency.

| Title | IBS-D | IBS-C | IBS-M | |||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | |

| Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of common internal diseases in Chinese medicine: diseases of modern medicine: irritable bowel disease | ||||||||||||

| * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Diagnosis and treatment consensus on irritable bowel syndrome with traditional Chinese medicine | ||||||||||||

| * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Consensus on irritable bowel syndrome by integrative medicine | ||||||||||||

| * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Diagnosis and treatment consensus on irritable bowel syndrome with traditional Chinese medicine (2017) | ||||||||||||

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||

| Diagnosis and treatment consensus on irritable bowel syndrome with integrative medicine (2017) | ||||||||||||

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||

| Title | FC | ||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | |

| Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of common internal diseases in Chinese medicine: diseases of modern medicine: functional constipation | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Diagnosis and treatment consensus on functional constipation with traditional Chinese medicine | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Diagnosis and treatment expert consensus on chronic constipation with traditional Chinese medicine (2017) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Diagnosis and treatment consensus on chronic constipation with integrative medicine | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

Tables 6 and 7 summarize the current recommendations for the Chinese formulas used for IBS and FC, respectively. For IBS-D with liver depression and spleen deficiency, the Tongxieyao formula was consistently advised by five CPGs. Similarly, the Liumo decoction was popularly recommended by five CPGs for the treatment of IBS-C with the pattern of liver depression and qi stagnation (In the 2008 IBS TCM guideline, the suggested formula was Wumo decoction combined with Sini powder, which could be considered as a modified Liumo decoction). For IBS-M, the recommendations were not uniform, and Wumei pills was relatively commonly acknowledged. For the previously mentioned four common patterns in FC, the recommended formulas were Maziren pills (intestinal excess heat), Liumo decoction (intestinal qi stagnation), Huangqi decoction (dual deficiency of the lung and spleen), and Jichuan decoction (spleen-kidney yang deficiency).

| Pattern | Formula | Patent medicine | |

| IBS-D | A | Tongxieyao formula and Sini powder | - |

| B | Shenlingbaizhu powder | Shenlingbaizhu granules | |

| C | Fuzilizhong decoction and Sishen pills | Gubenyichang tablets, Bupiyichang pills and Sishen pills | |

| D | Gegengqinlian decoction | Gegengqinlian micro pills | |

| E | Shenlingbaizhu powder | Shenlingbaizhu granules | |

| F | Wumei pills | - | |

| IBS-C | G | Sini powder, Wumo decoction and Liumo decoction | Simo decoction oral liquid and Liuweinengxiao capsules |

| H | Siwu decoction and Zengye decoction | Ziyinrunchang oral liquid | |

| I | Maziren pills | Marenrunchang pills | |

| J | Jichuan decoction | Qirongrunchang oral liquid | |

| K | Huangqi decoction | - | |

| IBS-M | L | Banxiaxiexin decoction Wumei pills | Wumei pills |

| Pattern | Decoction | Patent medicine |

| A | Maziren pills | Marenrunchang pills, Maren pills and Huanglianshangqing pills |

| B | Liumo decoction | Muxiangliqi tablets, Zhishidaozhi pills, Muxiangbinlang pills and Simotang oral liquid |

| C | Huangqi decoction | Bianmitong oral liquid and Qirongrunchang oral liquid |

| D | Jichuan decoction | Banliu pills and Congrongtongbian oral liquid |

| E | Zenye decoction | Tongle granules |

| F | Runchang pills | Wurenrunchang pills |

All TCM and IM CPGs provided recommendations for acupuncture therapy for both diseases, except for the 2008 IBS TCM guideline. For IBS-D, the primary acupoints included Zusanli (ST36), Tianshu (ST25), and Sanyinjiao (SP6). The primary acupoints for IBS-C and FC were basically the same, including Dachangshu (BL25), Tianshu (ST25), Zhigou (SJ6), and Fenglong (ST40). For FC, the 2011 and 2017 TCM guidelines also provided a recommendation for ear acupuncture. The acupoints included Wei (CO4), Dachang (CO7), Xiaochang (CO6), Zhichang (HX2), Jiaogan (AH6a), Pizhixia (AT4), and Sanjiao (CO17). Three or four points were recommended to be selected every time, and medium stimulation was to be given. Umbilical compression therapy was also mentioned in several guidelines, while the application of that therapy may need extra caution due to the limited instructions.

Currently, CPGs are a compulsory tool for daily clinical practice[49]. In China, more than two-thirds of medical practitioners would utilize CPGs routinely[50]. Therefore, in consideration of the position and function of these guidelines, they should be developed strictly on the basis of scientific evidence to reduce the potential for harm[49]. In this systematic review, 30 CPGs were included. Regardless of whether they pertained to IBS or FC, most WM CPGs were developed as EB guidelines, making them more convincing and practical. Some exceptional WM CPGs were established as CB-EB guidelines, whereas comprehensive evidence evaluation was found throughout the guidelines. Unsurprisingly, the majority of TCM CPGs and IM CPGs were developed as CB guidelines, which may be explained by the lack of TCM studies of satisfactory quality; however, this still limited the level of confidence in and practicability of these CPGs. Interestingly, the 2011 IBS and IM CPG was developed as a CB-EB guideline. However, the evidence in this CPG was almost all derived from review articles and consensus papers, which means that the level of evidence is weak.

There is no doubt that every guideline aims to establish a comprehensive and thorough set of medical statements. Nevertheless, current TCM or IM CPGs, which are not limited to IBS and FC, are basically CB guidelines. The core problem causing this phenomenon may be the unsatisfactory quality of the available scientific evidence. Although TCM has been applied in China for thousands of years, the first TCM RCT was published in 1982[51]. In addition, the late initiation of scientific studies on TCM has not fostered its development. According to the latest study, the quality of TCM RCTs is not optimal[52]. Therefore, the evidence in TCM and IM CPGs is not solid. We cannot deny that there have been some high-quality clinical trials conducted and published[53,54]. Based on the recommendation system, these intervention methods could receive a secondary level recommendation. TCM interventions were included in the ROME IV criteria. However, there is still a long way to go to enrich the global evidence. In addition, the available TCM and IM CPGs were developed on the basis of an expert consensus established by a questionnaire survey or at an academic conference. No systematic evidence search strategy was formulated. Hence, the method of CPG development should also have importance attached to it.

Both in the IBS and FC WM CPGs, a relatively comprehensive management algorithm was given. Antispasmodics and peppermint oil for pain, loperamide for diarrhea, and linaclotide for constipation were relatively strongly recommended in the treatment of IBS. Patients with FC could first be given empiric treatments, including fiber supplement and osmotic laxatives. Afterwards, if the response is inadequate, DD should be excluded, and then relatively aggressive interventions such as stimulant laxatives and prosecretory agents could be given. However, there are still some gaps that lack suitable treatments. For instance, in IBS management, how should clinicians address global symptom improvement or an unsatisfactory response to first-line therapies? In FC management, what interventions should be prescribed between the intervals of stimulant laxative treatment? Moreover, how can clinicians solve the problem of patients refusing to continue taking medications? In clinical practice, these issues may be addressed via TCM and IM.

First, herbal medicine (decoction and patent medicine) could be a second-line choice when the first-line agents are not effective enough to improve certain symptoms, or certain interventions cannot be continuously administered, for instance, Tongxieyao formula for IBS-D and Maziren pills for IBS-C and FC. Notably, the application of Chinese herbal medicine should be based on pattern differentiation, which requires a second round of TCM evaluation in clinical practice. Nevertheless, it is still necessary to conduct rigorous high-quality clinical studies to enhance the strength of evidence supporting these recommendations. Second, acupuncture could be considered when global IBS symptoms are not alleviated or patients discontinue pharmacological treatments. The application of acupuncture could also avoid potential drug-drug interactions between herbal medicines and other pharmaceuticals because the active components in Chinese formulas are complicated. Additionally, other external TCM therapies could be adjunctive treatment options after high-quality evidence has been established.

As mentioned above, herb-drug interactions are a potential concern in clinical practice. Some components originating from herbs may alter the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of pharmaceuticals, which then would influence their ultimate safety and efficacy[55]. Several studies have been conducted to reveal the potential interactions between common herbs and certain medications in a broad spectrum of diseases[56-58]. This is a positive trend in the IM research area; however, the accuracy of the data is still insufficient. Most TCM prescriptions in clinical practice were in the form of formulas. As a consequence, a single herb-drug interaction cannot represent the interactions with the whole formula. In our opinion, future studies could focus on the active components. The potential processes may include the following: (1) Recognizing major active components; (2) Testing the biological activity of the components; (3) Exploring the possible interactions based on the chemical structures; and (4) Verifying the interactions via in vitro and/or in vivo studies.

The basic concept of IM is to achieve synergistic therapeutic effects by combining WM with complementary and alternative medicine[59]. Currently, in China, as mentioned above, the use of TCM is routine in clinical practice. Therefore, the major form of IM in China is WM combined with TCM. However, we only identified three IM CPGs, and the contents were simple combinations of the available suggestions from TCM and WM, which means that the implementation of IM in clinical practice is still difficult. Thus, it is necessary to develop an independent IM CPG. This guideline should focus on the issues that clinical practitioners care the most about, such as management gaps that cannot be addressed with WM, advantages of TCM treatment options, and any potential gain or reduction in efficacy associated with IM interventions. Nonetheless, in consideration of the insufficient amount and unsatisfactory quality of the available evidence, this guideline can only be developed as a CB-EB guideline. However, in the future, when TCM and IM research is more mature, the IM CPG could definitely have stronger evidence and an improved impact.

In conclusion, there are relatively comprehensive management algorithms for IBS and FC that have already been developed. TCM has the potential to be used in the treatment of IBS and FC. With the support of high-quality clinical evidence, herbal medicine, acupuncture, and other external therapies could serve as supplemental second-line interventions for certain symptoms, therapy intervals, or special patients and could become therapeutic choices for the relief of global symptoms in IBS. In future, it is necessary to develop an independent IM CPG combining WM and TCM to guide clinical practice more efficiently.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional constipation (FC), two representative functional gastrointestinal disorders, are commonly encountered in daily clinical practice. In the outpatient setting, patients with IBS and FC account for 45.1% and 14.7% of all functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) patients, respectively. Nevertheless, the pathophysiologies of IBS and FC are still unclear, and the current interventions mostly address symptoms. Hence, in China, many clinicians consider integrating traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) into disease management. The effectiveness of TCM has been demonstrated through clinical experience and modern research, while the integration of Western medicine (WM) and TCM is still debated due to the unique medical system and various interventions involved in TCM. This systematic review is an innovative attempt to comprehensively summarize the recommendations with strong evidence in clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), aiming to identify the issues that might be addressed via integrative medicine (IM) and to provide new insights into future research.

The fundamental purpose of IM is to obtain synergistic therapeutic effects by combining two medical systems, namely, WM and TCM. In clinical practice, it is still difficult for doctors to identify the most suitable interventions and their timing. CPGs are systematically developed medical statements that contain the currently available and generally accepted interventions accompanied by the corresponding recommendations. By identifying the strong evidence-based (EB) recommendations in the CPGs, clinicians can not only have a better understanding of the current management of IBS and FC but also recognize clinical questions that have potential in further IM research.

The fundamental objective of this study was to systematically review the currently available CPGs and summarize the WM and TCM interventions that have strong evidence. More importantly, based on the available evidence, doctors and researchers can discover clinical issues that could be addressed with IM and then design relevant studies to verify the application.

Seven databases, namely, PUBMED, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, the Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (SinoMed), the Chinese Scientific Journal Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and the Wanfang database, were selected. The search terms were “clinical practice guideline”, “medical statement”, “expert consensus”, “irritable bowel syndrome”, “functional constipation”, and the corresponding synonyms. In addition, the official websites of national health institutions and handbooks were selected as supplementary resources. The extracted information included the initiating organization, title, year of publication, definitions of diseases, and details of the recommendations. According to the method of development of the CPGs, the included records were classified into EB guidelines, consensus-based (CB) guidelines, and consensus-based guidelines with no comprehensive consideration of the EB (CB-EB) guidelines. In addition, based on the quality of evidence, the strength of the recommendations related to the interventions was translated into a 4-grade system as follows: strong recommendation, recommendation, weak evidence, and insufficient evidence.

A total of 30 CPGs were included in the systematic review, including 16 IBS CPGs, 10 FC CPGs, and 4 CPGs for both. In general, most WM CPGs were developed as EB guidelines, while all TCM CPGs and most IM CPGs were CB guidelines. For IBS, antispasmodics and peppermint oil for pain, loperamide for diarrhea, and linaclotide for constipation had relatively high recommendation levels. Psyllium as a bulking agent, polyethylene glycol and lactulose as osmotic laxatives, bisacodyl and sodium picosulfate as stimulant laxatives, lubiprostone and linaclotide as prosecretory agents, and prucalopride were supported by relatively strong clinical evidence. TCM interventions were generally recommended based on expert consensus, which limited the recommendation level to weak or insufficient. For IBS, “liver depression and spleen deficiency” for diarrhea, “liver depression and qi stagnation” for constipation, and “cold-heat complex” for mixed type were the generally accepted patterns. The corresponding TCM formulas were the Tongxieyao formula, Liumo decoction, and Wumei pills, respectively. For FC, four patterns were generally acknowledged: intestinal excess heat, intestinal qi stagnation, dual deficiency of the lung and spleen, and spleen-kidney yang deficiency. Correspondingly, the specific formulas were Maziren pills, Liumo decoction, Huangqi decoction, and Jichuan decoction, respectively. The majority of TCM and IM CPGs recommended acupuncture therapy. For IBS-D, the primary acupoints included Zusanli (ST36), Tianshu (ST25), and Sanyinjiao (SP6). For IBS-C and FC, the primary acupoints included Dachangshu (BL25), Tianshu (ST25), Zhigou (SJ6), and Fenglong (ST40).

This systematic review innovatively summarize the CPGs regarding both TCM and WM over the last 30 years, providing a comprehensive picture of the current management of IBS and FC. The results were generated from generally acknowledged CPGs, which guarantees high levels of confidence in and clinical practicality of the conclusions. According to the results, relatively comprehensive management algorithms for IBS and FC have been established. For IBS, patients manifest with different predominant symptoms, and they are treated with antispasmodics and peppermint oil for pain, loperamide for diarrhea, and linaclotide for constipation. For FC patients, empiric agents such as fiber supplements and osmotic laxatives are administered first. If an inadequate response occurs, relatively aggressive interventions such as stimulant laxatives and prosecretory agents are considered after excluding defecatory disorder. However, there are still gaps in management that could be filled by TCM. For instance, herbal medicines could be considered as alternatives or used in combination when first-line medications are not effective enough. In addition, TCM external interventions could be applied when patients refuse pharmacological treatment or are concerned about herb-drug interactions. Nevertheless, to validate these findings, it is still necessary to conduct rigorous high-quality clinical studies to establish strong clinical evidence.

Based on the CPGs generated in recent decades, both WM and TCM have relatively comprehensive algorithms for IBS and FC treatment. The application of IM is promising in certain aspects of IBS and FC management. Future attention should be paid to the establishment of high-quality IM evidence, which would not only facilitate the management of IBS and FC but also serve as a template for IM application in common clinical diseases.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bouchoucha M, Ng QX, Sikiric P S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Xiong L, Gong X, Siah KT, Pratap N, Ghoshal UC, Abdullah M, Syam AF, Bak YT, Choi MG, Lu CL, Gonlachanvit S, Chua ASB, Chong KM, Ricaforte-Campos JD, Shi Q, Hou X, Whitehead WE, Gwee KA, Chen M. Rome foundation Asian working team report: Real world treatment experience of Asian patients with functional bowel disorders. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:1450-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Long Y, Huang Z, Deng Y, Chu H, Zheng X, Yang J, Zhu Y, Fried M, Fox M, Dai N. Prevalence and risk factors for functional bowel disorders in South China: a population based study using the Rome III criteria. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wall GC, Bryant GA, Bottenberg MM, Maki ED, Miesner AR. Irritable bowel syndrome: a concise review of current treatment concepts. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8796-8806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chang L, Lembo A, Sultan S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1149-72.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Ramkumar D, Rao SS. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:936-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ford AC, Lacy BE, Talley NJ. Irritable Bowel Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2566-2578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 50.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang B, Dong J, Zhou Z. Traditional Chinese Internal Medicine. Shanghai: Shang Hai Science and Technology Press 1985; . |

| 8. | Zhu JJ, Liu S, Su XL, Wang ZS, Guo Y, Li YJ, Yang Y, Hou LW, Wang QG, Wei RH, Yang JQ, Wei W. Efficacy of Chinese Herbal Medicine for Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:4071260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tang B, Zhang J, Yang Z, Lu Y, Xu Q, Chen X, Lin J. Moxibustion for Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:5105108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bahrami HR, Hamedi S, Salari R, Noras M. Herbal Medicines for the Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Electron Physician. 2016;8:2719-2725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cheng CW, Bian ZX, Wu TX. Systematic review of Chinese herbal medicine for functional constipation. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4886-4895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yao YB, Cao YQ, Guo XT, Yi J, Liang HT, Wang C, Lu JG. Biofeedback therapy combined with traditional chinese medicine prescription improves the symptoms, surface myoelectricity, and anal canal pressure of the patients with spleen deficiency constipation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:830714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ferreira AS, Lopes AJ. Chinese medicine pattern differentiation and its implications for clinical practice. Chin J Integr Med. 2011;17:818-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Field MJ, Lohr KN. Clinical practice guidelines: directions for a new program: National Academies Press, 1990. |

| 15. | Wollersheim H, Burgers J, Grol R. Clinical guidelines to improve patient care. Neth J Med. 2005;63:188-192. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Cruse H, Winiarek M, Marshburn J, Clark O, Djulbegovic B. Quality and methods of developing practice guidelines. BMC Health Serv Res. 2002;2:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Brosseau L, Rahman P, Toupin-April K, Poitras S, King J, De Angelis G, Loew L, Casimiro L, Paterson G, McEwan J. A systematic critical appraisal for non-pharmacological management of osteoarthritis using the appraisal of guidelines research and evaluation II instrument. PLoS One. 2014;9:e82986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | American Gastroenterology Association. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2105-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, Emmanuel A, Houghton L, Hungin P, Jones R, Kumar D, Rubin G, Trudgill N, Whorwell P; Clinical Services Committee of The British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut. 2007;56:1770-1798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 591] [Cited by in RCA: 527] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gwee KA, Bak YT, Ghoshal UC, Gonlachanvit S, Lee OY, Fock KM, Chua AS, Lu CL, Goh KL, Kositchaiwat C, Makharia G, Park HJ, Chang FY, Fukudo S, Choi MG, Bhatia S, Ke M, Hou X, Hongo M; Asian Neurogastroenterology and Motility Association. Asian consensus on irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1189-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | China Society of Digestive Diseases in Chinese Medicine. Consensus on standard management of irritable bowel syndrome in TCM. Chin J Tradit Chin Med Pharm. 2010;1062-1065. |

| 22. | Andresen V, Keller J, Pehl C, Schemann M, Preiss J, Layer P. Irritable bowel syndrome--the main recommendations. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:751-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Speciality Committee of Digestive Diseases. Chinese Association of Integrative Medicine. Consensus on irritable bowel syndrome by Integrative Medicine. Chin J Integr Tradit West Med. 2011;31:587-590. |

| 24. | Weinberg DS, Smalley W, Heidelbaugh JJ, Sultan S; Amercian Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1146-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fukudo S, Kaneko H, Akiho H, Inamori M, Endo Y, Okumura T, Kanazawa M, Kamiya T, Sato K, Chiba T, Furuta K, Yamato S, Arakawa T, Fujiyama Y, Azuma T, Fujimoto K, Mine T, Miura S, Kinoshita Y, Sugano K, Shimosegawa T. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:11-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Quigley EM, Fried M, Gwee KA, Khalif I, Hungin AP, Lindberg G, Abbas Z, Fernandez LB, Bhatia SJ, Schmulson M, Olano C, LeMair A; Review Team:. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Global Perspective Update September 2015. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:704-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management [Accessed 4 April 2017]. Available from: URL: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg61 Cited 28 February 2019. |

| 28. | Cooperative Group of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology. Gastrointestinal Motility Group of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology. Expert consensus on irritable bowel syndrome in China. Chin J Dig. 2016;36:299-312. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Krarup AL, Engsbro ALØ, Fassov J, Fynne L, Christensen AB, Bytzer P. Danish national guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Dan Med J. 2017;64. [PubMed] |

| 30. | China Society of Digestive Diseases in Chinese Medicine. Consensus on standard management of irritable bowel syndrome in TCM (2017). J Tradit Chin Med. 2017;58:1614-1620. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Wu JC, Chan AO, Chan YW, Cheung GC, Cheung TK, Kwan AC, Leung VK, Mak AD, Sze WC, Wong R. The current treatment landscape of irritable bowel syndrome in adults in Hong Kong: consensus statements. Hong Kong Med J. 2017;23:641-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Speciality Committee of Digestive Diseases. Chinese Association of Integrative Medicine, Consensus on irritable bowel syndrome by Integrative Medicine (2017). Chin J Integr Tradit West Med Dig. 2018;26:227-232. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Song KH, Jung HK, Kim HJ, Koo HS, Kwon YH, Shin HD, Lim HC, Shin JE, Kim SE, Cho DH, Kim JH, Kim HJ; Clinical Practice Guidelines Group Under the Korean Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Korea, 2017 Revised Edition. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24:197-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | China Society of Digestive Diseases in Chinese Medicine. Diagnosis and treatment consensus on chronic constipation with Traditional Chinese Medicine. Beijing J Tradit Chin Med. 2011;30:3-7. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Lindberg G, Hamid SS, Malfertheiner P, Thomsen OO, Fernandez LB, Garisch J, Thomson A, Goh KL, Tandon R, Fedail S, Wong BC, Khan AG, Krabshuis JH, LeMair A; World Gastroenterology Organisation. World Gastroenterology Organisation global guideline: Constipation--a global perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:483-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bove A, Pucciani F, Bellini M, Battaglia E, Bocchini R, Altomare DF, Dodi G, Sciaudone G, Falletto E, Piloni V, Gambaccini D, Bove V. Consensus statement AIGO/SICCR: diagnosis and treatment of chronic constipation and obstructed defecation (part I: diagnosis). World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1555-1564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Bove A, Bellini M, Battaglia E, Bocchini R, Gambaccini D, Bove V, Pucciani F, Altomare DF, Dodi G, Sciaudone G, Falletto E, Piloni V. Consensus statement AIGO/SICCR diagnosis and treatment of chronic constipation and obstructed defecation (part II: treatment). World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4994-5013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Gastrointestinal Motility Group of Digestive Disease Branch. Colorecatal Group of Surgery Branch of Chinese Medical Association, Diagnosis and treatment guideline of chronic constipation in China (2013). Chin J Gastroenterol. 2013;605-612. |

| 39. | American Gastroenterological Association. Bharucha AE, Dorn SD, Lembo A, Pressman A. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:211-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Shin JE, Jung HK, Lee TH, Jo Y, Lee H, Song KH, Hong SN, Lim HC, Lee SJ, Chung SS, Lee JS, Rhee PL, Lee KJ, Choi SC, Shin ES; Clinical Management Guideline Group under the Korean Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Functional Constipation in Korea, 2015 Revised Edition. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:383-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | China Society of Digestive Diseases in Chinese Medicine. Diagnosis and treatment expert consensus on chronic constipation with Traditional Chinese Medicine (2017). J Tradit Chin Med. 2017;58:1345-1350. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 42. | Digestive Disease Committee of Chinese Association of Integrative Medicine. Diagnosis and treatment consensus on chronic constipation with Integrative Medicne. Chin J Integr Tradit West Med Dis. 2018;26:18-26. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 43. | Vitton V, Damon H, Benezech A, Bouchard D, Brardjanian S, Brochard C, Coffin B, Fathallah N, Higuero T, Jouët P, Leroi AM, Luciano L, Meurette G, Piche T, Ropert A, Sabate JM, Siproudhis L; SNFCP CONSTI Study Group. Clinical practice guidelines from the French National Society of Coloproctology in treating chronic constipation. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:357-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ghoshal UC, Sachdeva S, Pratap N, Verma A, Karyampudi A, Misra A, Abraham P, Bhatia SJ, Bhat N, Chandra A, Chakravartty K, Chaudhuri S, Chandrasekar TS, Gupta A, Goenka M, Goyal O, Makharia G, Mohan Prasad VG, Anupama NK, Paliwal M, Ramakrishna BS, Reddy DN, Ray G, Shukla A, Sainani R, Sadasivan S, Singh SP, Upadhyay R, Venkataraman J. Indian consensus on chronic constipation in adults: A joint position statement of the Indian Motility and Functional Diseases Association and the Indian Society of Gastroenterology. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2018;37:526-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Paré P, Bridges R, Champion MC, Ganguli SC, Gray JR, Irvine EJ, Plourde V, Poitras P, Turnbull GK, Moayyedi P, Flook N, Collins SM. Recommendations on chronic constipation (including constipation associated with irritable bowel syndrome) treatment. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21 Suppl B:3B-22B. [PubMed] |

| 46. | China Association of Chinese Medicine. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of common internal diseases in Chinese Medicine: diseases of modern medicine. Beijing: China Press of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2008; . |

| 47. | Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Quigley EM; Task Force on the Management of Functional Bowel Disorders. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109 Suppl 1:S2-26; quiz S27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 403] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Mearin F, Ciriza C, Mínguez M, Rey E, Mascort JJ, Peña E, Cañones P, Júdez J. Clinical Practice Guideline: Irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and functional constipation in the adult. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016;108:332-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:527-530. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Wu MJ, Zhang SJ, ZC Z, Zhang Y, Li X. Use and demand of clinical practice guidelines in China. Chin J Med Libr Inf Sci. 2016;25:37-42. |

| 51. | Chen KJ, Qian ZH, Zhang WQ, Guan WR, Hao XG, Chen XJ, Liu FZ, Zhang MF, Shi XP, Zhang NR. Effectiveness analysis for double blinded treatment with refined coronary tablets on angina pectoris leaded by coronary heart disease in 112 cases. J Med Res. 1982;11:015. |

| 52. | He J, Du L, Liu G, Fu J, He X, Yu J, Shang L. Quality assessment of reporting of randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding in traditional Chinese medicine RCTs: a review of 3159 RCTs identified from 260 systematic reviews. Trials. 2011;12:122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Zhong LLD, Cheng CW, Kun W, Dai L, Hu DD, Ning ZW, Xiao HT, Lin CY, Zhao L, Huang T, Tian K, Chan KH, Lam TW, Chen XR, Wong CT, Li M, Lu AP, Wu JCY, Bian ZX. Efficacy of MaZiRenWan, a Chinese Herbal Medicine, in Patients With Functional Constipation in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1303-1310.e18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Liu Z, Yan S, Wu J, He L, Li N, Dong G, Fang J, Fu W, Fu L, Sun J, Wang L, Wang S, Yang J, Zhang H, Zhang J, Zhao J, Zhou W, Zhou Z, Ai Y, Zhou K, Liu J, Xu H, Cai Y, Liu B. Acupuncture for Chronic Severe Functional Constipation: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:761-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Singh A, Zhao K. Herb-Drug Interactions of Commonly Used Chinese Medicinal Herbs. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2017;135:197-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Ziemann J, Lendeckel A, Müller S, Horneber M, Ritter CA. Herb-drug interactions: a novel algorithm-assisted information system for pharmacokinetic drug interactions with herbal supplements in cancer treatment. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Zuo HL, Yang FQ, Hu YJ. Investigation of Possible Herb-Drug Interactions for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2019;45:548-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Wilson V, Maulik SK. Herb-Drug Interactions in Neurological Disorders: A Critical Appraisal. Curr Drug Metab. 2018;19:443-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Dobos G, Tao I. The model of Western integrative medicine: the role of Chinese medicine. Chin J Integr Med. 2011;17:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |