Published online Nov 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i21.3446

Peer-review started: July 12, 2019

First decision: August 2, 2019

Revised: August 10, 2019

Accepted: September 13, 2019

Article in press: September 13, 2019

Published online: November 6, 2019

Processing time: 130 Days and 1.5 Hours

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common digestive system disease with a high incidence rate and is common in women. The cause of IBS remains unclear. Some studies have shown that mental and psychological diseases are independent risk factors for IBS. At present, the treatment of IBS is mainly symptomatic treatment. Clinically, doctors also use cognitive behavioral therapy to improve patients' cognitive ability to diseases and clinical symptoms. In recent years, exercise therapy has attracted more and more attention from scholars. Improving the symptoms of IBS patients through psychosomatic treatment strategy may be a good treatment method.

To explore the effects of an intervention of cognitive behavioral therapy combined with exercise (CBT+E) on the cognitive bias and coping styles of patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D); and to provide a theoretical reference for the management of IBS.

Sixty IBS-D patients and thirty healthy subjects were selected. The 60 IBS-D patients were randomly divided into experimental and control groups. The experimental group was treated with the CBT+E intervention, while the control group was treated with conventional drugs without any additional intervention. The cognitive bias and coping styles of the participants were evaluated at baseline and after 6 wk, 12 wk and 24 wk using the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ), Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS) and Pain Coping Style Questionnaire (CSQ) instruments, and the intervention effect was analyzed using SPSS 17.0 statistical software.

At baseline, the scores on the various scales showed that all subjects had cognitive bias and adverse coping styles. The IBS Symptom Severity Scale (IBS-SSS) scores, ATQ total scores, DAS scores and CSQ scores of the two groups were not significantly different (P > 0.05). Compared with baseline, after 6 wk of the CBT+E intervention, there were significant differences in the ATQ scores, the dependence and total scores on the DAS, and the catastrophization, distraction and prayer scores on the CSQ (P < 0.05). After 12 wk, there were significant differences in the scores for perfectionism on the DAS and in the scores for reinterpretation, neglect and pain behavior on the CSQ in the experimental group (P < 0.05). After 24 wk, there were significant differences in the vulnerability, dependence, perfectionism, and total scores on the DAS and in the catastrophization, distraction and prayer scores on the CSQ in the experimental group (P < 0.01). The IBS-SSS scores were negatively correlated with the ATQ and DAS total scores (P < 0.05) but were positively correlated with the CSQ total score (P < 0.05).

Intervention consisting of CBT+E can correct the cognitive bias of IBS-D patients and eliminate their adverse coping conditions. CBT+E should be promoted for IBS and psychosomatic diseases.

Core tip: Cognitive bias and negative coping styles are common in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). We have conducted continuous observation and research on the clinical somatic symptoms, cognitive bias and coping styles of patients with comprehensive treatment for 24 wk, and found that compared with single conventional treatment, it has better effect on relieving clinical symptoms, which proves that it is of great significance to improve cognitive bias and adverse coping styles of patients with diarrhea-type IBS through cognitive behavioral therapy combined with exercise intervention.

- Citation: Zhao SR, Ni XM, Zhang XA, Tian H. Effect of cognitive behavior therapy combined with exercise intervention on the cognitive bias and coping styles of diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome patients. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(21): 3446-3462

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i21/3446.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i21.3446

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a group of functional diseases with continuous or intermittent attacks of symptoms such as abdominal pain, abdominal distension, or changes in defecation habits or stool characteristics due to dysfunction of the nervous system[1]. According to clinical characteristics, it can be divided into diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D), constipation-predominant IBS (IBS-C) or mixed IBS (IBS-M); IBS-D is the most common. The etiology and pathogenesis of IBS remain unclear and may be related to gastrointestinal motility, visceral sensations, brain-gut regulatory abnormalities, inflammation, mental psychology and other factors[2]. Digestion and dysfunction of the intestinal tract in IBS patients are manifested as abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation and alternation of stool dryness and thinness. Compared with organic gastroenteropathy, IBS is more prone to cognitive bias and emotional disorders, which often lead to "abnormal" psychological behavioral patterns, which mainly include anxiety, depression, fear, runaway emotions, sensitivity, hypochondriasis, somatization disorders and other mental and psychological problems. These cognitive biases and negative coping styles affect the nervous system function of patients through the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, causing increased vagus nerve excitability, stimulation of intestinal peristalsis and mucosal gland secretion, and gastrointestinal symptoms that often cannot immediately relieved[3]. Therefore, it is very important to correct patients' cognitive biases and coping styles for the fundamental treatment of these diseases. At present, the treatment of IBS is mainly limited to symptomatic treatment, including adjustments to diet structure, psychological and behavioral treatment, and simple drug treatment, and the effect has not been ideal. In recent years, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has become an important modality of IBS treatment[4]. Cognitive behavioral therapy is a structured, short-term and cognitive approach to psychotherapy. It is considered to be an important component of IBS patients with moderate to severe disease or unresponsive to initial drug therapy and comorbid psychological factors. The application of exercise therapy in the treatment of chronic diseases has gradually attracted the attention of researchers. Aerobic exercise with moderate intensity and an appropriate duration has a positive effect on body and mind regulation[5]. Based on these findings, this study used Baduanjin health qigong as an auxiliary therapy supplementing CBT therapy and carried out 24 wk of the combined intervention with IBS-D patients, observed the intervention effects on the cognitive bias and coping styles of IBS-D patients, and discussed the application value of an intervention of CBT combined with exercise (CBT+E) in the prevention and treatment of IBS.

Sixty patients with IBS-D were selected from January to October 2018 from the Digestive Department of the Fourth People's Hospital of Shenyang City, Liaoning Province, and 30 healthy subjects were recruited as controls. The sixty IBS-D patients were aged 30-40 years old and were divided into an experimental group (CBT+E) and a control group, with 30 people in each group. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Compliance with the IBS-D Rome III diagnostic criteria published by the American Gastroenterology Academic Year 2006[6]; (2) No restriction on sex, with patient age ranging from 30 to 40 years old; (3) Illness lasting for 6-24 wk; (4) No organic diseases identified through endoscopy, X-ray, B-ultrasound or laboratory examination; and (5) Normal blood examination and normal heart, liver and kidney function. The exclusion criteria included the following: (1) Inflammatory bowel disease or other organic diseases that would affect the evaluation of patient symptoms; (2) Severe psychological diseases such as schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder and suicidal tendency[7]; (3) Psychological treatment for other diseases; (4) The occurrence of serious negative life events during treatment; (5) Allergy history and drug and food allergy during the test period; and (6) Pregnancy or lactation.

The general demographic data of the subjects are shown in Table 1. The basic conditions of the subjects in each group were similar, and there was no significant difference in age, body mass index (BMI), educational level or course of disease between groups (P > 0.05). During the initial assessment, the purpose and significance of the study, the research methods and some possible impacts on the patient were explained to the patients. The participants voluntarily participated in the study and signed an informed consent form. During the experiment, 3 subjects withdrew for different reasons. One person from the experimental group was unable to complete the experiment, and another patient suffered from other diseases and received treatment. One participant in the control group suffered from other intestinal diseases. There were twenty-eight patients in the final experimental group, 29 patients in the conventional drug control group and 30 subjects in the healthy control group.

| Group | Number | Sex, male/female | Age, yr | Time of education, yr | BMI, kg/m2 | Course of disease, yr |

| CBT+E | 28 | 7/21 | 33.75 ± 2.57 | 14.57 ± 2.54 | 21.67 ± 1.38 | 8.68 ± 1.80 |

| Control | 29 | 7/22 | 36.86 ± 2.54 | 15.03 ± 2.54 | 21.90 ± 1.36 | 8.66 ± 2.00 |

| Healthy | 30 | 7/23 | 35.30 ± 2.75 | 14.93 ± 2.55 | 22.27 ± 1.63 | - |

| t/χ2 | 0.02 | 9.47 | 3.37 | 1.22 | 3.29 | |

| P value | 0.98 | 0.48 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.77 |

In order to implement the whole experiment smoothly according to the training plan, a pre-experiment was carried out before the formal experiment. In the pre-experiment, the subjects in the experimental group were clearly explained, and the eight-part brocade movement demonstration and essentials were demonstrated. Through the practice, the training process and movement requirements were familiar with, and the training time and arrangement were clearly defined. The subjects in the control group adopted the conventional comprehensive treatment scheme. First, drugs for regulating intestinal motility were used to address the symptoms of diarrhea and constipation. For patients with abdominal pain, symptomatic treatment, e.g., antispasmodic and analgesic drugs, was used together with drugs for regulating intestinal flora. For patients with anxiety disorder, anti-anxiety and antidepressant drugs were used to reduce the sensitivity of internal organs. The subjects in the experimental group adopted CBT+E based on a conventional comprehensive treatment scheme. Among them, cognitive behavioral therapy is to improve the psychological problems it presents by changing the patient’s views and attitudes towards people, oneself and things. The focus is to reduce the mental burden of the patient on the disease, explain the patient’s illness in detail and patiently, eliminate the patient’s doubts, block the vicious circle of bad psychology, and establish a good cognition of the disease. For example, CBT required doctors and laboratory personnel to first understand the cognitive characteristics and symptom-inducing factors of the subjects and evaluate their cognitive characteristics, emotional responses and coping styles with regard to events; then, disease-related psychoeducation, the identification and correction of negative automatic thoughts, cognitive restructuring, and relaxation training were conducted with the subjects once a week to enable the patients to establish a correct adaptive cognitive mode. The Baduanjin training required the subjects to engage in the continuous exercise intervention no fewer than 4 times/wk, 2 times/d (in the morning and afternoon) and 45 min/session for 24 wk. Baduanjin professional coaches and medical staff provided comprehensive and systematic guidance on the technical essentials and duration of the Baduanjin exercises. The coaches, doctors and nurses established good relations with the subjects, fully understood the disease condition, comprehended the emotional state of the patients, and obtained their trust and cooperation. During the tests, all the subjects in each group followed their doctors’ advice, and the relevant test personnel provided safety education and relevant information and addressed matters requiring attention. Each subject in the CBT+E group received video data so that all the subjects could standardize and master the eight-segment brocade. They were introduced to the detailed exercises of the eight-segment brocade so that they could use it in their daily study and exercise. Telephone supervision and return visits were regularly conducted, timely skill guidance was provided, random checks occurred, and each exercise was recorded. If any problems were encountered, the subjects could communicate with the doctors and coaches at any time.

Before the test, all the scale assessors received unified scale assessment training to standardize the evaluation of the test battery. The three groups of subjects were evaluated with the following scales at baseline and 6 wk, 12 wk and 24 wk after the initiation of the intervention. (1) The IBS Symptom Severity Scale (IBS-SSS) was evaluated. The symptom severity score and symptom frequency score for IBS were divided into 4 grades. The scale was scored along 5 dimensions: The degree of abdominal pain, the frequency of abdominal pain, the degree of abdominal distension, the degree of satisfaction with defecation and the degree of influence on life. (2) Cognitive and behavioral characteristics were assessed with the following: (I) the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ), which is a self-assessment questionnaire with all items describing negative experiences of depression, and the scores, categorized into 5 grades, have been positively correlated with the degree of depression; and (II) the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS), which assesses potentially deeper cognitive structures, including vulnerability, attraction and exclusion, perfectionism, compulsion, approval seeking, dependence, autonomous attitude, cognitive philosophy and other factors. (3) Coping styles were assed with the Pain Coping Style Questionnaire (CSQ), which includes 8 dimensions: Reinterpreting pain: Overcoming one's own state, ignoring pain perception, catastrophizing, increasing activity, engaging in pain behavior, distracting attention, and praying; this instrument makes it possible to evaluate the coping style of IBS and chronic pain patients with regard to pain symptoms.

SPSS 17.0 statistical software was used to process the data. Descriptions of the measurement data were expressed as the mean ± SD. The general demographic data of the patients were statistically analyzed by t tests and χ2 tests. Changes in the IBS-SSS, ATQ, DAS, and CSQ scores were analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA within and between groups. A normality test of the values showed that all the data conformed to a normal distribution. For the differences, a standard significance level was adopted, with differences being considered significant at P < 0.05 and extremely significant at P < 0.01.

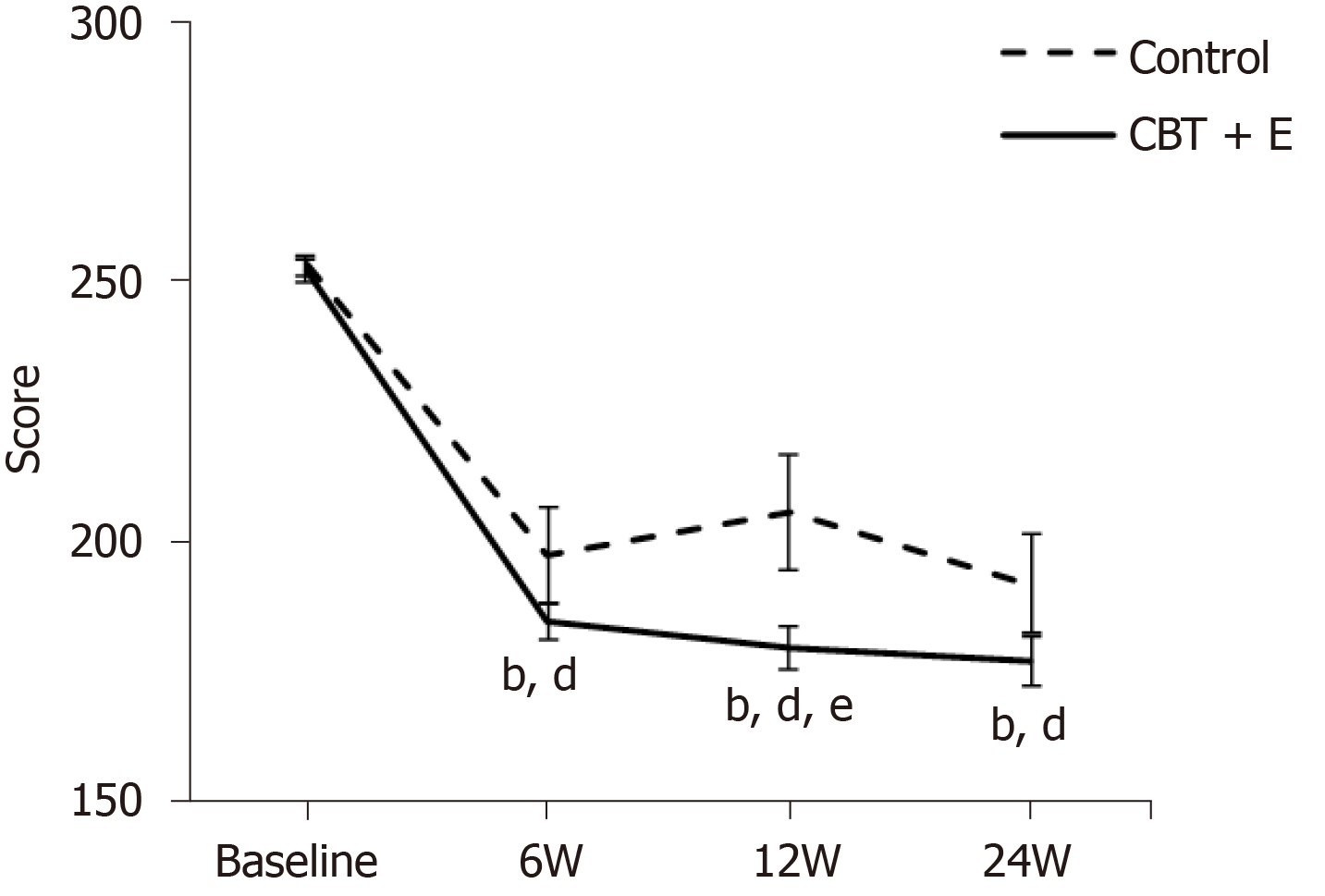

Table 2 shows the IBS-SSS symptom score test before and after intervention in ech group of patients. As shown in Figure 1, there were no significant differences in IBS-SSS scores between the two groups at baseline (P > 0.05). Compared with the control group, after 6 wk, 12 wk and 24 wk of the combined intervention, the IBS-SSS scores in the experimental group showed significant differences (P < 0.01). Compared with baseline, the IBS-SSS scores in the experimental group were significantly different after 6 wk, 12 wk and 24 wk of the intervention (P < 0.05). There was a significant difference in the scores of the experimental group between 12 wk of intervention and 6 wk of intervention (P < 0.01). The IBS-SSS scores in the experimental group showed a significant difference between 24 wk of intervention and 12 wk of intervention (P < 0.05).

| Group | n | Baseline | 6 wk | 12 wk | 24 wk |

| CBT+E | 28 | 252.07 ± 2.32 | 184.75 ± 3.56 | 179.85 ± 4.05 | 177.14 ± 4.61 |

| Control | 29 | 253.13 ± 1.97 | 197.51 ± 9.04 | 205.68 ± 10.89 | 191.89 ± 9.39 |

Table 3 shows the results of repeated-measures ANOVA, with the IBS-SSS score serving as the dependent variable in the experimental group. After the CBT+E intervention, there were extremely significant differences between test points at different times (P < 0.01). In the time*group interaction effect, the IBS-SSS scores showed extremely significant differences (P < 0.01), while for the group effects, the IBS-SSS scores showed extremely significant differences between the test and control groups (P < 0.01).

| Time main effect | Interaction | Group main effect | ||||

| F | P value | F | P value | F | P value | |

| IBS-SSS | 3292.810 | < 0.001 | 115.158 | < 0.001 | 71.795 | < 0.001 |

As shown in Table 4, the total ATQ, DAS and CSQ scores of the experimental group before and after 24 wk of the intervention were statistically significant between the groups (P < 0.05). Compared with healthy people, IBS-D patients have significant negative automatic thinking (P < 0.01). Compared with healthy people, the dysfunctional attitude of IBS-D patients is widespread. The perfectionism score on the DAS scale showed no significant differences (P > 0.05) across the experimental and healthy control groups, and the remaining 7 dimensions and the total score showed extremely significant differences (P < 0.01). Compared with the healthy control group, IBS-D patients chose particular coping styles more often, such as catastrophization and prayer (P < 0.01), and fewer other coping styles, such as diversion of attention (P < 0.05).

| Scale | Dimensions | IBS-D (n = 57) | Healthy control (n = 30) | t | P value |

| ATQ | 63.32 ± 9.44 | 44.33 ± 3.51 | 10.609 | 0.000 | |

| DAS | Vulnerability | 17.96 ± 2.36 | 14.67 ± 1.26 | 7.099 | 0.002 |

| Absorption/rejection | 15.46 ± 3.67 | 11.17 ± 2.26 | 5.837 | 0.000 | |

| Perfectionism | 16.98 ± 2.98 | 15.87 ± 2.30 | 1.785 | 0.059 | |

| Mandatory | 17.89 ± 3.74 | 11.93 ± 2.19 | 8.019 | 0.000 | |

| Seek approval | 18.09 ± 3.47 | 13.40 ± 2.31 | 6.652 | 0.002 | |

| Dependence | 18.30 ± 2.62 | 13.20 ± 2.02 | 9.276 | 0.043 | |

| Autonomous attitude | 18.56 ± 3.74 | 12.83 ± 2.70 | 7.410 | 0.041 | |

| Cognitive philosophy | 17.16 ± 2.12 | 12.87 ± 2.86 | 7.915 | 0.007 | |

| Total score | 137.39 ± 17.30 | 113.67 ± 10.35 | 6.875 | 0.008 | |

| CSQ | f1 Reinterpret | 9.42 ± 2.91 | 9.43 ± 2.27 | -0.019 | 0.513 |

| f2 Overcome | 17.42 ± 2.61 | 17.57 ± 2.14 | -0.262 | 0.205 | |

| f3 Ignore | 13.27 ± 2.67 | 14.81 ± 3.00 | -2.358 | 0.337 | |

| f4 Catastrophization | 19.82 ± 3.14 | 11.57 ± 4.76 | 9.689 | 0.004 | |

| f5 Increase activity | 12.74 ± 3.12 | 13.67 ± 3.85 | -1.215 | 0.175 | |

| f6 Pain behavior | 13.93 ± 3.21 | 12.67 ± 3.20 | 1.744 | 0.890 | |

| f7 Divert attention | 9.68 ± 4.21 | 14.67 ± 3.25 | -5.642 | 0.025 | |

| f8 Pray | 12.74 ± 3.12 | 9.27 ± 2.11 | 5.452 | 0.005 |

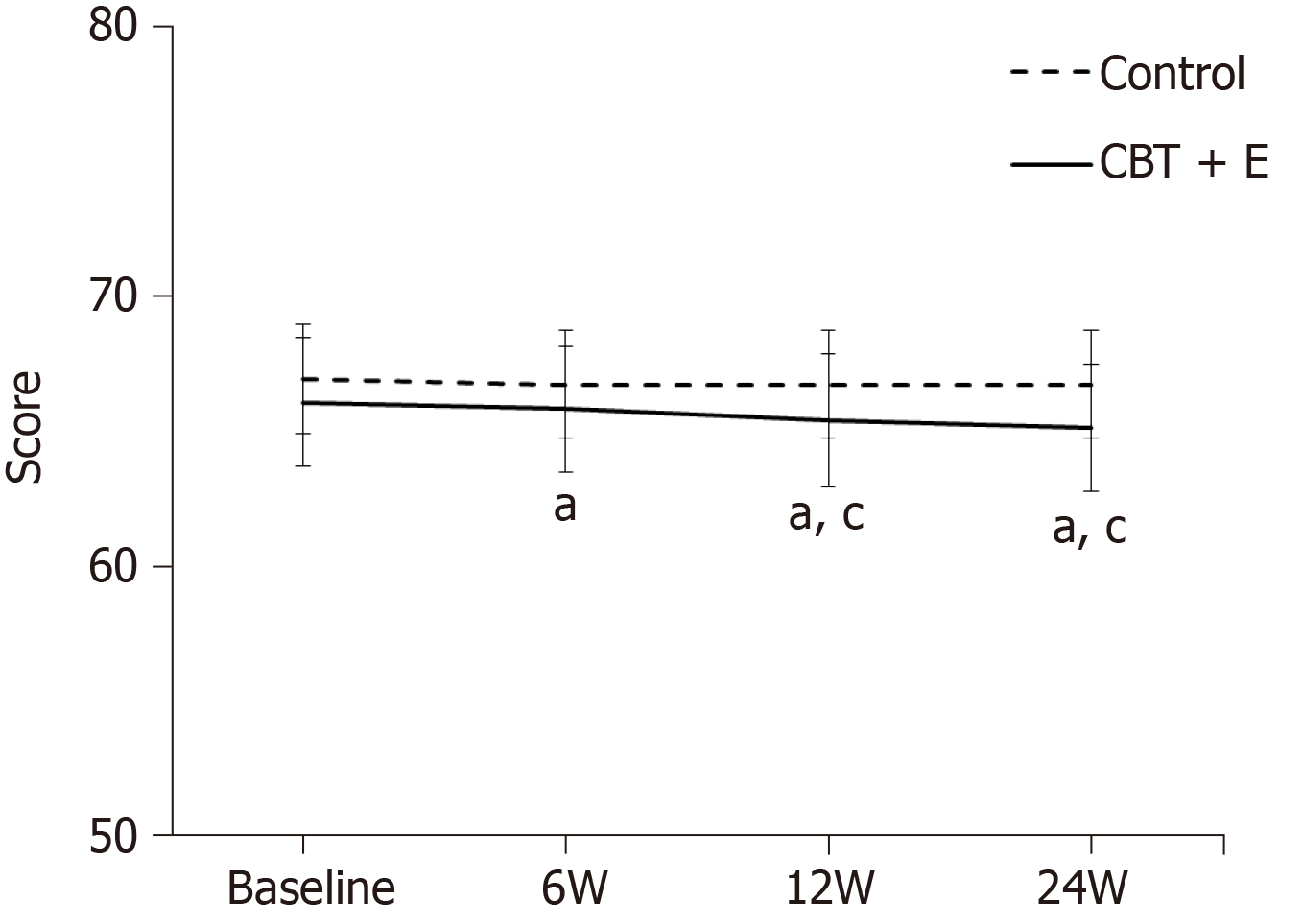

Table 5 shows the changes of cognitive bias scores before and after the intervention. As shown in Figure 2, at baseline, there was no significant difference in the ATQ scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). Compared with the control group, after 6 wk of the combined intervention, the ATQ scores showed significant differences (P < 0.05), and after 12 wk and 24 wk, the ATQ scores showed significant differences (P < 0.05). Compared with baseline, after 12 wk of the intervention, the ATQ scores in the experimental group began to show significant differences (P < 0.05), and after 12 wk and 24 wk, the ATQ scores continued to show significant differences (P < 0.05).

| CBT+E (n = 28) | Control (n = 29) | ||||||||

| Baseline | 6 wk | 12 wk | 24 wk | Baseline | 6 wk | 12 wk | 24 wk | ||

| ATQ | 66.96 ± 2.02 | 66.75 ± 2.01 | 65.66 ± 1.03 | 64.98 ± 2.23 | 66.10 ± 2.39 | 65.85 ± 2.33 | 65.42 ± 2.45 | 65.14 ± 2.36 | |

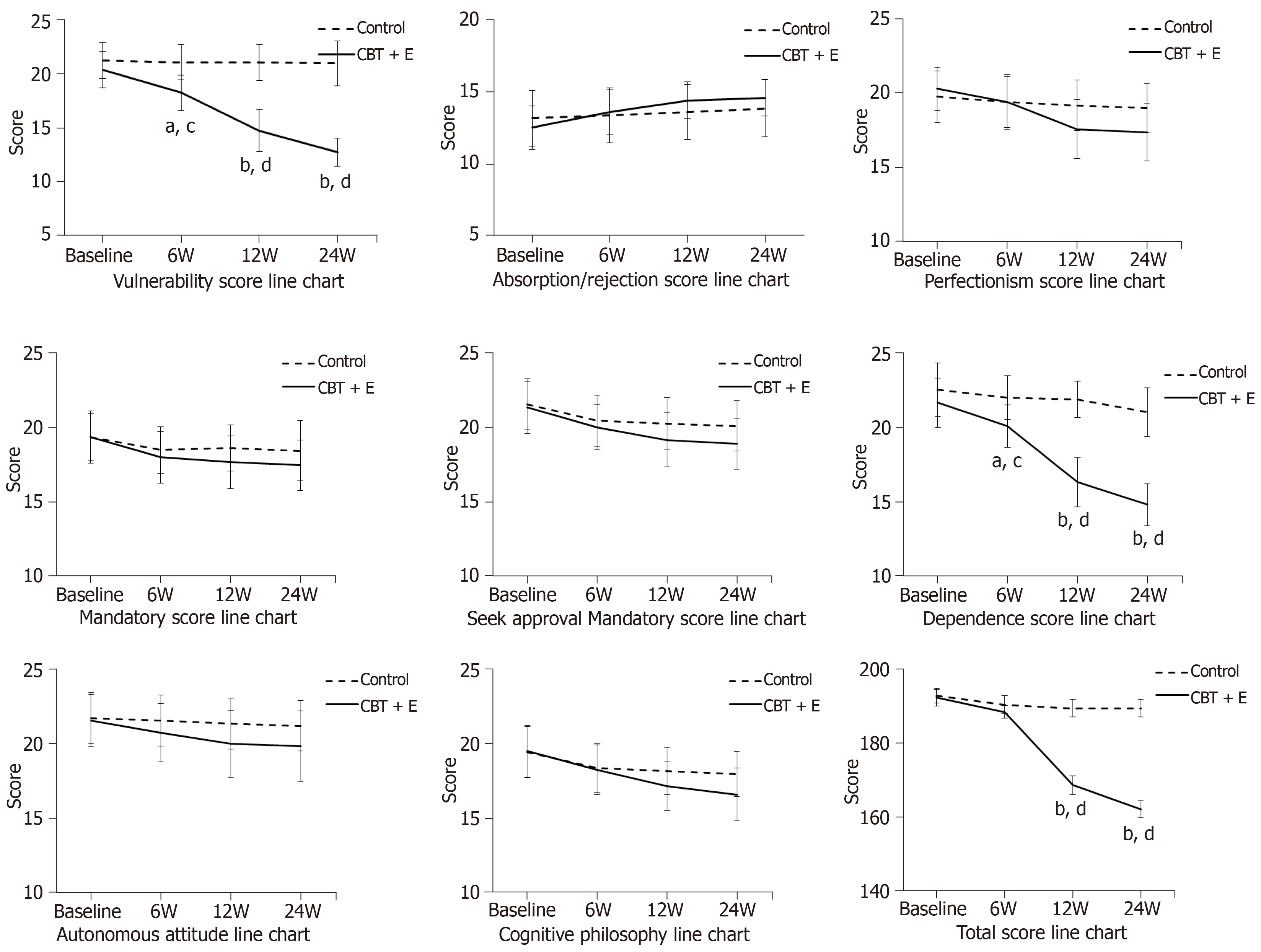

| Vulnerability | 20.39 ± 1.66 | 18.25 ± 1.66 | 14.75 ± 1.97 | 12.75 ± 1.77 | 21.27 ± 1.68 | 21.10 ± 1.65 | 21.06 ± 1.68 | 20.99 ± 2.10 | |

| Absorption/rejection | 12.53 ± 1.52 | 13.60 ± 1.59 | 14.42 ± 1.28 | 14.60 ± 1.28 | 13.17 ± 1.94 | 13.37 ± 1.91 | 13.62 ± 1.91 | 13.86 ± 1.99 | |

| Perfectionism | 20.28 ± 1.46 | 19.39 ± 1.72 | 17.57 ± 1.98 | 17.35 ± 1.92 | 19.75 ± 1.72 | 19.41 ± 1.84 | 19.17 ± 1.69 | 19.00 ± 1.64 | |

| DAS | Mandatory | 19.37 ± 1.76 | 18.00 ± 1.74 | 17.67 ± 1.78 | 17.46 ± 1.68 | 19.37 ± 1.59 | 18.48 ± 1.57 | 18.62 ± 1.54 | 18.43 ± 2.03 |

| Seek approval | 21.35 ± 1.74 | 20.03 ± 1.55 | 19.17 ± 1.80 | 18.89 ± 1.68 | 21.58 ± 1.70 | 20.44 ± 1.74 | 20.27 ± 1.72 | 20.10 ± 1.69 | |

| Dependence | 21.67 ± 1.65 | 20.10 ± 1.42 | 16.32 ± 1.65 | 14.82 ± 1.41 | 22.55 ± 1.80 | 22.01 ± 1.45 | 21.90 ± 1.22 | 21.03 ± 1.65 | |

| Autonomous attitude | 21.57 ± 1.75 | 20.75 ± 1.95 | 20.00 ± 2.26 | 19.85 ± 2.36 | 21.72 ± 1.70 | 21.55 ± 1.72 | 21.37 ± 1.71 | 21.20 ± 1.69 | |

| Cognitive philosophy | 19.50 ± 1.75 | 18.25 ± 1.66 | 17.14 ± 1.64 | 16.60 ± 1.79 | 19.44 ± 1.70 | 18.37 ± 1.63 | 18.17 ± 1.60 | 17.96 ± 1.52 | |

| Total score | 192.32 ± 2.22 | 188.50 ± 1.71 | 168.67 ± 2.56 | 162.10 ± 2.33 | 192.89 ± 2.00 | 190.48 ± 2.38 | 189.48 ± 2.38 | 189.48 ± 2.38 | |

As shown in Figure 3, at baseline, there were no significant differences in the scores for the DAS dimensions between the two groups (P > 0.05). Compared with the control group, there were significant differences in the vulnerability, dependency and total scores after 6 wk of the combined intervention (P < 0.05). After 12 wk, the perfectionism scores showed a significant difference (P < 0.05). After 24 wk, the perfection scores showed a significant difference (P < 0.05), and the vulnerability, dependency and total scores showed an extremely significant difference (P < 0.01). There were no significant differences in the other 5 dimensions of the DAS before and after the intervention (P > 0.05). Compared with baseline, after 6 wk of the intervention, the vulnerability, perfectionism, dependency and total scores of the CBT+E group showed significant differences (P < 0.05). After 12 wk, the perfectionism scores showed a significant difference (P < 0.05), and the vulnerability, dependency and total scores showed extremely significant differences (P < 0.01). After 24 wk, the score changes showed results similar to those after 12 wk. Compared with baseline, the other 5 dimensions of the DAS showed no significant differences (P > 0.05).

Table 6 shows the results of repeated-measures ANOVA, with the ATQ and DAS scores for each test group serving as the dependent variables. After the intervention, the ATQ total score and the DAS dimension scores and total scores had extremely significant differences between different test points (P < 0.01). In the time*group interaction effect, there were significant differences in the ATQ total scores and DAS scores and total scores (P < 0.01). In the group effect, the total ATQ scores between the experimental group and control group were significantly different (P < 0.05). The vulnerability, perfectionism, dependence and total scores on the DAS were significantly different (P < 0.01). There were no significant differences in the five dimensions of attraction and rejection, compulsion, seeking approval, autonomous attitude and cognitive philosophy (P > 0.05).

| Time main effect | Interaction | Group main effect | ||||

| F | P value | F | P value | F | P value | |

| ATQ | 52.475 | < 0.001 | 26.296 | < 0.001 | 4.094 | 0.048 |

| DAS | 2240.350 | < 0.001 | 2033.203 | < 0.001 | 102.742 | < 0.001 |

| Vulnerability | 190.521 | < 0.001 | 59.642 | < 0.001 | 0.409 | 0.525 |

| Absorption/rejection | 341.422 | < 0.001 | 154.348 | 0.001 | 4.242 | 0.044 |

| Perfectionism | 246.569 | < 0.001 | 35.920 | < 0.001 | 2.321 | 0.133 |

| Mandatory | 432.932 | < 0.001 | 33.320 | < 0.001 | 2.722 | 0.105 |

| Seek approval | 1994.091 | < 0.001 | 1859.358 | < 0.001 | 94.206 | < 0.001 |

| Dependence | 52.797 | < 0.001 | 18.439 | < 0.001 | 3.406 | 0.070 |

| Autonomous attitude | 526.055 | < 0.001 | 66.836 | < 0.001 | 2.001 | 0.163 |

| Cognitive philosophy | 24495.725 | < 0.001 | 17739.892 | < 0.001 | 456.001 | < 0.001 |

| Total score | 52.475 | < 0.001 | 26.296 | < 0.001 | 4.094 | 0.048 |

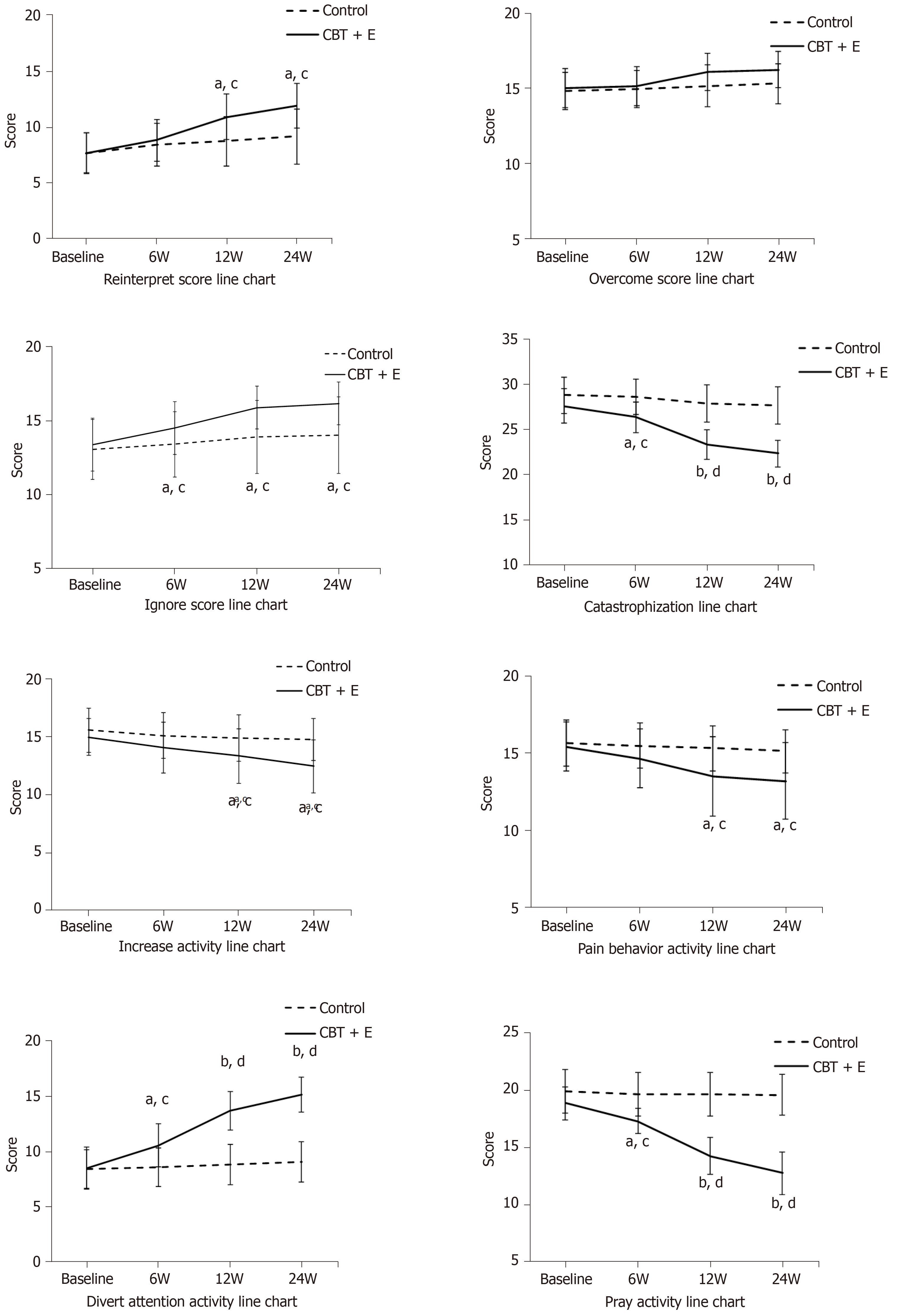

Table 7 shows the changes of coping style scores before and after the intervention. As shown in Figure 4, at baseline, there was no significant difference in the CSQ scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). Compared with the control group, after 6 wk of the combined intervention, there were significant differences in the catastrophization, distraction and prayer scores (P < 0.05). After 12 wk, there was a significant difference in four dimensions: reinterpretation, neglect, increased activity and pain behavior (P < 0.05); additionally, there was an extremely significant difference in the catastrophization, distraction and prayer scores (P < 0.01). After 24 wk, the reinterpretation, neglect, increased activity and pain behavior scores showed significant differences (P < 0.05), and the catastrophization, distraction and prayer scores showed extremely significant differences (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference in the CSQ one-dimensional overcoming score before and after the intervention (P > 0.05). Compared with baseline, the CBT+E group showed significant differences in the catastrophization, distraction and prayer scores after 6 wk of the intervention (P < 0.05). Only after 12 wk of the intervention did significant differences in reinterpretation, neglect, increased activity and pain behaviors appear (P < 0.05). After 24 wk, there were significant differences in reinterpretation, neglect, increased activity and pain behavior (P < 0.05) and significant differences in the catastrophization, distraction and prayer scores (P < 0.01).

| Dimensions | CBT+E (n = 28) | Control (n = 29) | ||||||

| Baseline | 6 wk | 12 wk | 24 wk | Baseline | 6 wk | 12 wk | 24 wk | |

| Reinterpret | 7.67 ± 1.80 | 8.82 ± 1.88 | 10.92 ± 2.03 | 11.92 ± 2.03 | 7.65 ± 1.81 | 8.41 ± 1.91 | 8.75 ± 2.21 | 9.17 ± 2.47 |

| Overcome | 15.03 ± 1.31 | 15.17 ± 1.30 | 16.10 ± 1.22 | 16.25 ± 1.20 | 14.82 ± 1.25 | 14.96 ± 1.26 | 15.17 ± 1.39 | 15.31 ± 1.31 |

| Ignore | 13.39 ± 1.79 | 14.50 ± 1.79 | 15.89 ± 1.44 | 16.17 ± 1.44 | 13.06 ± 2.03 | 13.41 ± 2.22 | 13.91 ± 2.46 | 14.03 ± 2.58 |

| Catastrophization | 27.57 ± 1.91 | 26.35 ± 1.66 | 23.32 ± 1.65 | 22.32 ± 1.51 | 28.79 ± 2.00 | 28.58 ± 1.97 | 27.89 ± 2.07 | 27.68 ± 2.05 |

| Increase activity | 14.96 ± 1.59 | 14.07 ± 2.22 | 13.35 ± 2.34 | 12.46 ± 2.28 | 15.58 ± 1.91 | 15.10 ± 1.98 | 14.89 ± 1.98 | 14.75 ± 1.82 |

| Pain behavior | 15.42 ± 1.59 | 14.67 ± 1.88 | 13.50 ± 2.57 | 13.21 ± 2.49 | 15.68 ± 1.49 | 15.48 ± 1.45 | 15.31 ± 1.44 | 15.13 ± 1.40 |

| Divert attention | 8.50 ± 1.87 | 10.57 ± 1.95 | 13.71 ± 1.76 | 15.17 ± 1.58 | 8.44 ± 1.74 | 8.62 ± 1.74 | 8.86 ± 1.82 | 9.06 ± 1.83 |

| Pray | 18.85 ± 1.43 | 17.28 ± 1.11 | 14.25 ± 1.62 | 12.75 ± 1.89 | 19.86 ± 1.92 | 19.65 ± 1.89 | 19.65 ± 1.89 | 19.58 ± 1.78 |

Table 8 shows the results of repeated-measures ANOVA, with the CSQ scores in each group serving as the dependent variables. Significant differences in the CSQ dimension scores were observed between different test points under the different interventions in each test group (P < 0.01). In the time*group interaction effect, the scores on the CSQ dimensions showed extremely significant differences (P < 0.01). For the group effect, the catastrophization, distraction and prayer scores in the experimental group were significantly different (P < 0.01), and the reinterpretation, neglect, increased activity and pain behavior scores in the CSQ were significantly different (P < 0.05), while the overcoming scores were not significantly different (P > 0.05).

| Time main effect | Interaction | Group main effect | ||||

| F | P value | F | P value | F | P value | |

| Reinterpret | 358.691 | < 0.001 | 102.798 | < 0.001 | 6.319 | 0.015 |

| Overcome | 118.479 | < 0.001 | 30.007 | < 0.001 | 2.944 | 0.092 |

| Ignore | 178.747 | < 0.001 | 42.734 | < 0.001 | 6.807 | 0.012 |

| Catastrophization | 1493.579 | < 0.001 | 625.333 | < 0.001 | 46.485 | < 0.001 |

| Increase activity | 115.845 | < 0.001 | 38.786 | < 0.001 | 6.688 | 0.012 |

| Pain behavior | 54.750 | < 0.001 | 19.504 | < 0.001 | 6.326 | 0.015 |

| Divert attention | 1393.227 | < 0.001 | 973.004 | < 0.001 | 47.800 | < 0.001 |

| Pray | 676.394 | < 0.001 | 568.470 | < 0.001 | 75.735 | < 0.001 |

After 24 wk of the CBT+E intervention, the cognitive bias and coping styles of the subjects in the experimental group changed to a certain extent. First, the 24-wk values of the above indexes in the CBT+E group were compared with the baseline values, i.e., 24 wk-baseline, and then, the differences between the test groups were analyzed. The IBS-SSS scores were taken as dependent variables, and the average total scores of the ATQ, DAS, and CSQ were taken as independent variables for linear regression analysis.

According to Table 9, the Pearson correlation coefficients of the IBS-SSS scores with the ATQ, DAS and CSQ scores were -0.330, 0.744, and 0.763, respectively, with significant coefficients (P < 0.05), indicating significant correlations among the IBS-SSS, ATQ, DAS and CSQ and reliable correlations among the different variables.

The scores on the IBS-SSS, ATQ, DAS and CSQ before and after the CBT+E intervention in the experimental group were analyzed and showed a linear relationship. Therefore, it is of great practical significance to establish the corresponding linear regression model according to the fitting effect of the model.

As shown in Table 10, the adjusted R2 = 0.702 conforms to the goodness-of-fit level for the regression equation, F = 18.872, P < 0.01. The linear relationships between the IBS-SSS scores and the ATQ, DAS, and CSQ scores were significant when the coefficients were different from 0, and a linear equation was established.

| R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Standard error | F | P value |

| 0.838 | 0.702 | 0.665 | 0.649 | 18.872 | 0.000 |

Table 11 shows the totality of the equation. The regression equation coefficient table shows that the significance levels of the regression coefficients for the ATQ, DAS and CSQ scores were 0.033, 0.028 and 0.036, respectively. The significance test results were less than 0.05, which means that the variables were significantly correlated and consistent with the results obtained in correlation analysis. Linear regression equations can be established according to the following model, with X1 representing ATQ, X2 representing DAS, and X3 representing CSQ: Y(IBS-SSS) = -95.862 - 0.261X1 - 0.393X2 + 0.305X3. The research results showed that after 6 wk, 12 wk and 24 wk of the CBT+E intervention, the IBS-SSS scores of the subjects in the experimental group were significantly negatively correlated with the ATQ and DAS scores and were significantly positively correlated with the CSQ scores. When the IBS-SSS scores changed, the ATQ and DAS scores decreased, and the CSQ scores increased. This finding shows that changes in cognitive bias (ATQ, DAS) and adverse coping styles can predict changes in the IBS-SSS scores in the study group. This analysis of the improvements in the clinical symptoms of the patients shows that a change in cognitive bias and a positive improvement in adverse coping styles can promote the recovery of the patients.

| Variable | Regression coefficient | Standard error | Normalization coefficient | t | P value |

| Constant | -95.862 | 4.871 | — | -19.681 | 0.000 |

| ATQ | -0.261 | 0.115 | -0.256 | -2.269 | 0.033 |

| DAS | -0.393 | 0.168 | -0.420 | -2.343 | 0.028 |

| CSQ | 0.305 | 0.138 | 0.400 | 2.215 | 0.036 |

IBS is a group of intestinal dysfunction syndromes caused by abdominal discomfort or abdominal pain with abnormal defecation. From a physiological perspective, the gastrointestinal tract is the only organ under the combined control of the intestinal nervous system, autonomic nervous system and central nervous system in the body, which has both sensory functions and motor functions. Therefore, IBS is a typical psychosomatic disease in the digestive system[8,9]. Studies have confirmed that IBS patients generally have cognitive biases and negative coping styles, accompanied by negative emotions[10]. Clinically, treatment is often limited to improving symptoms through drugs or a single session of CBT therapy. However, for patients, it is difficult to realize the integrated adjustment of the brain-gut axis if they cannot adopt a unified treatment strategy that combines mental and physical health[11]. Even if the cognitive bias of patients is corrected, their negative coping styles cannot be improved, and the disease cannot be fundamentally treated. Studies have indicated that exercise can improve the mood of IBS patients and easily promote positive coping styles. Therefore, on the foundation of CBT, exercise therapy was used as an auxiliary therapy to correct patients' cognitive bias and generate positive coping styles, which may be an important strategy for IBS rehabilitation treatment. This study takes IBS-D patients as the research object. The most common clinical classification is diarrhea, and one of the main factors affecting the occurrence of IBS is intestinal flora. Some studies have confirmed that IBS-D flora have more serious imbalances and more obvious differences than IBS-C and IBS-M patients, thus providing a theoretical basis for our study.

The main clinical manifestations of patients with IBS-D are abnormal defecation shape, abdominal distension, abdominal discomfort and abdominal pain. The etiological mechanism of the disease is relatively complex. It is presumed that the causes may be psychological factors, dietary factors, heredity, infection, visceral sensory abnormalities and intestinal motility abnormalities[12,13]. A large number of studies worldwide show that CBT is an effective treatment for IBS. Jones et al[14] showed that in treating IBS patients, CBT combined with mebeverine is better than mebeverine alone. Mikocka-Walus et al[15] found that CBT is more effective than general education. Behavioral therapy has been increasingly and more widely applied in the treatment of physical and mental diseases; in this regard, researchers have also paid an increasing amount of attention to sports interventions[16]. As a form of traditional Chinese sports, health qigong Baduanjin has the good effects of calming the heart and qi, improving breathing, calming the five major internal organs and correcting body shape. It has obvious prevention and treatment effects on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, endocrinological diseases, metabolic diseases and digestive diseases[17]. Among these effects, the third type, "regulating the spleen and lifting the stomach alone", can improve constipation symptoms, regulate intestinal flora, stimulate appetite and have obvious improvement effects on gastrointestinal functions[18]. Sun Hongmei[19], using quantitative culture methods and counting living bacteria, recorded changes in the intestinal flora of elderly participants after practicing Baduanjin for 24 wk. The results showed that practicing Baduanjin had a positive effect on the growth and distribution of intestinal flora of elderly patients and could effectively improve the intestinal microecological balance. Lackner et al[20] carried out 8-segment brocade training twice a week for 60 min and 14 wk for subjects suffering from IBS, and they confirmed the effect of this exercise therapy in terms of improving patient symptoms, improving quality of life and reducing medical expenses[21]. In this paper, fitness Baduanjin was selected as an adjuvant therapy for CBT treatment. It was found that the CBT+E intervention was better than CBT treatment alone in relieving clinical symptoms, which is consistent with the relevant research results.

Cognitive bias is a phenomenon in which people often distort or fail to objectively perceive themselves, others or the external environment due to their own or situational reasons[22]. Most patients with IBS-D have a negative tendency when looking at problems, i.e., patients have negative automatic thinking, ideas and thoughts with regard to the disease, which reflect adverse reactions such as fragility, perfection, and dependence. They think that they cannot be cured. Therefore, they have fluctuating emotions, sensitive and suspicious mental and psychological problems, and persistent negative emotions and mental tension that often increase visceral sensitivity and aggravate the disease[23]. CBT has a significant psychotherapeutic effect and a positive effect on relieving chronic pain. It is also helpful for improving patients' understanding and experience of pain behaviors, thus confirming that patients with chronic pain have some catastrophizing cognitive attitudes[24]. Some researchers believe that functional disorder is a characteristic symptom of IBS and constitutes the disease's susceptibility to negative events. Beppu et al[25] believe that when faced with negative life events, if individuals hold extremely negative cognitive biases, including negative self-evaluation, generalization and catastrophization, their negative life events will trigger unreasonable self-attribution and present a spiraling vicious circle of development, ultimately affecting the whole illness. Using a specific hypnotherapy, Harder et al[26] found that hypnotherapy can significantly improve the cognitive bias of patients and eventually improve their gastrointestinal symptoms. Pimentel et al[27] conducted biofeedback therapy with 60 IBS patients. Their results showed that biofeedback therapy can improve the symptoms of abdominal pain and emergency defecation, reduce the patients' worries about gastrointestinal function and improve their overall well-being. All of these findings confirm that CBT has a positive effect on IBS patients. Some researchers have pointed out that during moderate aerobic exercise, most areas of the brain are in a relatively inhibited state, improving the functions of the frontal lobe and the parietal cortex of the brain, avoiding excessive nervous activity, regulating brain balance, promoting blood circulation, increasing gastrointestinal peristalsis, and thus effectively relieving the pain and discomfort of patients, allowing a gradual return to normal life[28]. In this paper, a 12-wk period of health qigong Baduanjin combined with CBT therapy was selected as the intervention. It was found that the combined therapy was more effective in correcting the cognitive bias of patients, producing positive coping styles and increasing treatment compliance.

Coping style refers to the methods or means that people adopt in the face of various inevitable stressful scenarios and related situations of emotional distress[29]. Patients with IBS-D often choose adverse coping styles, such as catastrophization and prayer, and give up active coping styles, such as overcoming their own state, ignoring adverse feelings and diverting attention, thus causing the illness to repeatedly lead to poor therapeutic effects[30]. Poor coping styles will cause many negative emotions, and vagus nerve excitability will continue to increase, which will lead to increased intestinal peristalsis and intestinal secretion, affect gastrointestinal digestion and absorption capacity, and cause gastrointestinal dysfunction more serious symptoms[31]. IBS patients often place difficulties in front of themselves when they encounter problems and are not good at adopting appropriate coping methods to face the current situation[32]. CBT coping skills training, such as relaxation training, respiratory training, hypnotherapy and biofeedback therapy, can help patients identify uncontrollable stressors. Johnston et al[33] improved the abdominal discomfort and defecation habits of IBS patients through hypnotherapy, thus improving their overall well-being and positive coping styles. In Gonsalkorale et al[34], 75 IBS patients were randomly divided into an intestinal hypnotherapy plus conventional drug therapy group and a simple conventional drug therapy group as the interventions. Their results showed that the former had more obvious intestinal symptoms and a positive coping attitude than the latter. This study found that IBS patients adopt more negative coping styles than do healthy people, which suggests that IBS patients have poor coping styles that have a direct impact on the therapeutic effect of an intervention. Through the CBT+E intervention, the negative coping styles of patients were improved. At the same time, their ability to use some positive coping styles also improved, and the disease was effectively treated. In this study, a simple and easy-to-understand Baduanjin exercise to relieve mood and relax the body was used for adjuvant therapy. It was found that the CBT+E intervention has a more significant effect on the coping abilities of IBS patients, which is consistent with the relevant research results. In summary, this article selected health qigong Baduanjin as an auxiliary therapy supplementing CBT treatment and found that a CBT+E intervention can correct the cognitive bias of patients, alleviate intestinal pain, improve patients' normal adjustment ability to intestinal movement and autonomic nerve, correct intestinal dysfunction, effectively relieve dysfunctional attitudes, and generate positive coping styles. At the same time, through a good social support environment, patients are urged to use correct coping styles to reduce or relieve psychosomatic damage caused by symptoms, thus improving quality of life[35] and achieving a relatively satisfactory curative effect of IBS treatment. A CBT+E intervention can be used as an effective treatment strategy for IBS and should be clinically promoted.

This study has several limitations that need to be discussed. First, the number of research subjects is relatively small, and the observation indexes are not rich enough to reflect the actual clinical conditions of more subjects. Secondly, the subjects selected in this study are all patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome, and there is no research and analysis on other types of the disease. Third, this test analyzed the different index data of 24 wk of intervention training, and did not carry out follow-up testing and analysis, which can be carried out in future research to further explore. For the test, the combination of pharmacotherapy may produce important bias, which requires longer time and more systematic test analysis to explore its internal change trend.

IBS-D patients generally have a certain degree of cognitive bias and adverse coping styles, thus affecting the therapeutic effects of any intervention and their daily quality of life. An intervention consisting of CBT combined with Baduanjin was more helpful in correcting the negative automatic thinking of IBS-D patients, forming appropriate coping styles, and effectively improving symptoms. The intervention consisting of CBT combined with Baduanjin is a therapeutic strategy for IBS-D that should be promoted for the clinical and family rehabilitation of some psychosomatic diseases.

Compared with organic gastroenteropathy, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is more prone to cognitive bias and emotional disorders, which can lead to "abnormal" psychological behavior patterns. IBS can affect the nervous system function of patients through hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and so on, cause increased vagus nerve excitability, stimulate intestinal peristalsis and mucosal gland secretion, and cannot relieve gastrointestinal symptoms. Therefore, it is very important to correct patients' cognitive biases and coping styles for the fundamental treatment of diseases.

Studies have confirmed that IBS patients generally have cognitive biases and negative coping styles, accompanied by negative emotions. Clinically, the improvement of symptoms is often limited to drugs or single CBT therapy. However, if the treatment strategy of combining mental psychology and body cannot be adopted in a way of both body and mind, it is difficult to realize the integrated regulation of brain-intestine axis, and the disease cannot be fundamentally solved. According to some research reports, exercise can improve the mood of IBS patients. Therefore, on the basis of cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise therapy is used as an auxiliary therapy to correct the cognitive bias of patients and produce positive coping styles, which may be an important strategy for rehabilitation treatment of IBS.

The research objective of this study was to explore the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy combined with exercise intervention on cognitive bias and coping styles of patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS to provide a theoretical reference for the prevention and treatment of diarrhea-predominant IBS.

We retrospectively analyzed 60 patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS aged 30-40 years and 30 healthy subjects recruited from January 2018 to October 2018. They were randomly divided into the experimental group and the control group. All subjects received 24 wk of continuous intervention program. Statistical analysis was conducted through repeated measurement variance analysis, and correlation and regression analysis were used to determine correlation.

Our study found that patients with IBS have obvious cognitive bias and negative coping styles compared with normal people. IBS-SSS symptom score is significantly correlated with ATQ, DAS and CSQ scores.

Cognitive behavioral therapy combined with exercise intervention can well correct the cognitive bias of diarrhea IBS patients and eliminate the adverse coping conditions of patients, which is of great significance for the treatment of IBS and psychosomatic diseases.

The number of subjects included in our study is relatively small, the intervention time is relatively short, and there are not enough observation indicators to more fully reflect the clinical situation of patients. In future research, more attention should be paid to the above deficiencies.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dumitrascu DL, Ng QX, Vento S S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Drossman DA. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1366] [Cited by in RCA: 1375] [Article Influence: 152.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | O'Malley D. Immunomodulation of enteric neural function in irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7362-7366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ringel-Kulka T, Choi CH, Temas D, Kim A, Maier DM, Scott K, Galanko JA, Ringel Y. Altered Colonic Bacterial Fermentation as a Potential Pathophysiological Factor in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1339-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Simrén M, Törnblom H, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE. Management of the multiple symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:112-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, Bajor A, Sadik R. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:915-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Engsbro AL, Simren M, Bytzer P. Short-term stability of subtypes in the irritable bowel syndrome: prospective evaluation using the Rome III classification. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:350-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Moser G, Trägner S, Gajowniczek EE, Mikulits A, Michalski M, Kazemi-Shirazi L, Kulnigg-Dabsch S, Führer M, Ponocny-Seliger E, Dejaco C, Miehsler W. Long-term success of GUT-directed group hypnosis for patients with refractory irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:602-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nahon S, Lahmek P, Durance C, Olympie A, Lesgourgues B, Colombel JF, Gendre JP. Risk factors of anxiety and depression in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2086-2091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gracie DJ, Irvine AJ, Sood R, Mikocka-Walus A, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC. Effect of psychological therapy on disease activity, psychological comorbidity, and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:189-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee YJ, Park KS. Irritable bowel syndrome: emerging paradigm in pathophysiology. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2456-2469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 11. | Kew KM, Nashed M, Dulay V, Yorke J. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for adults and adolescents with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD011818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Şimşek I. Irritable bowel syndrome and other functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45 Suppl:S86-S88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ng QX, Soh AYS, Loke W, Lim DY, Yeo WS. The role of inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). J Inflamm Res. 2018;11:345-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Jones M, Koloski N, Boyce P, Talley NJ. Pathways connecting cognitive behavioral therapy and change in bowel symptoms of IBS. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70:278-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mikocka-Walus A, Bampton P, Hetzel D, Hughes P, Esterman A, Andrews JM. Cognitive-behavioural therapy has no effect on disease activity but improves quality of life in subgroups of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li L, Xiong L, Zhang S, Yu Q, Chen M. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schumann D, Anheyer D, Lauche R, Dobos G, Langhorst J, Cramer H. Effect of Yoga in the Therapy of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1720-1731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Whelan K, Quigley EM. Probiotics in the management of irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29:184-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hajizadeh Maleki B, Tartibian B, Mooren FC, FitzGerald LZ, Krüger K, Chehrazi M, Malandish A. Low-to-moderate intensity aerobic exercise training modulates irritable bowel syndrome through antioxidative and inflammatory mechanisms in women: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Cytokine. 2018;102:18-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Krasner SS, Katz LA, Gudleski GD, Holroyd K. Self-administered cognitive behavior therapy for moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome: clinical efficacy, tolerability, feasibility. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:899-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Montgomery GH, David D, Kangas M, Green S, Sucala M, Bovbjerg DH, Hallquist MN, Schnur JB. Randomized controlled trial of a cognitive-behavioral therapy plus hypnosis intervention to control fatigue in patients undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:557-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vargas S, Antoni MH, Carver CS, Lechner SC, Wohlgemuth W, Llabre M, Blomberg BB, Glück S, DerHagopian RP. Sleep quality and fatigue after a stress management intervention for women with early-stage breast cancer in southern Florida. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21:971-981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Grinsvall C, Törnblom H, Tack J, Van Oudenhove L, Simrén M. Psychological factors selectively upregulate rectal pain perception in hypersensitive patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:1772-1782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ng QX, Venkatanarayanan N, Kumar L. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for the Management of Pediatric Migraine. Headache. 2017;57:349-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Doi H, Beppu N, Odawara S, Tanooka M, Takada Y, Niwa Y, Fujiwara M, Kimura F, Yanagi H, Yamanaka N, Kamikonya N, Hirota S. Neoadjuvant short-course hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy (SC-HART) combined with S-1 for locally advanced rectal cancer. J Radiat Res. 2013;54:1118-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Harder H, Parlour L, Jenkins V. Randomised controlled trials of yoga interventions for women with breast cancer: a systematic literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:3055-3064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pimentel M. Review article: potential mechanisms of action of rifaximin in the management of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43 Suppl 1:37-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Van Oudenhove L, Crowell MD, Drossman DA, Halpert AD, Keefer L, Lackner JM, Murphy TB, Naliboff BD, Levy RL. Biopsychosocial Aspects of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;S0016-5085(16)00218-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rahnama M, Shahdadi H, Bagheri S, Moghadam MP, Absalan A. The Relationship between Anxiety and Coping Strategies in Family Caregivers of Patients with Trauma. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:IC06-IC09. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sherwin LB, Leary E, Henderson WA. Effect of Illness Representations and Catastrophizing on Quality of Life in Adults With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2016;54:44-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Krogsgaard LR, Engsbro AL, Bytzer P. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in Denmark. A population-based survey in adults ≤50 years of age. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:523-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pergamin-Hight L, Pine DS, Fox NA, Bar-Haim Y. Attention bias modification for youth with social anxiety disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57:1317-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Johnston JM, Shiff SJ, Quigley EM. A review of the clinical efficacy of linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:149-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Gonsalkorale WM, Toner BB, Whorwell PJ. Cognitive change in patients undergoing hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:271-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Geng Z, Ogbolu Y, Wang J, Hinds PS, Qian H, Yuan C. Gauging the Effects of Self-efficacy, Social Support, and Coping Style on Self-management Behaviors in Chinese Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41:E1-E10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |