Published online Oct 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i20.3377

Peer-review started: June 29, 2019

First decision: July 31, 2019

Revised: August 24, 2019

Accepted: September 11, 2019

Article in press: September 11, 2019

Published online: October 26, 2019

Processing time: 120 Days and 13.6 Hours

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a CD30-positive T cell lymphoma, a rare type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The current World Health Organization classification system divides ALCLs into anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive and ALK-negative groups. ALCL rarely presents in the gastrointestinal tract.

A 54-year-old male was admitted to the department of gastroenterology for abdominal pain. He presented with lower abdominal pain, diarrhea and recurrent oral and penile ulcers. He was misdiagnosed with Behcet's disease and treated with prednisone. But after one month, he was hospitalized in another hospital for reexamination. This time, the lesion on the penis was biopsied for histological examination. The final pathological diagnosis was ALCL, ALK-negative. The patient was treated with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone chemotherapy. However, he died within one month.

Gastrointestinal ALCL needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis to avoid delaying treatment. Repeated biopsy is the most important for early diagnosis and treatment.

Core tip: Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a CD30-positive T cell lymphoma, a rare kind of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. ALCL rarely presents with the intestinal tract. In addition to reporting an anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative ALCL involving the colon and penis in a 54-year-old male, our literature review identified 3 cases of gastrointestinal ALCL with several interesting clinicopathological features.

- Citation: Luo J, Jiang YH, Lei Z, Miao YL. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma masquerading as Behcet's disease: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(20): 3377-3383

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i20/3377.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i20.3377

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a peripheral T-cell lymphoma and is characterized by strong expression of CD30 (Ki-1)[1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, ALCLs are divided into four groups: Systemic anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive ALCL (ALCL, ALK+), systemic ALK-negative ALCL (ALCL, ALK-), primary cutaneous ALCL (pC-ALCL), and breast implant-associated ALCL (BI-ALCL)[2]. Both ALK-positive and ALK-negative patients are predominantly male[1]. Two groups involve both lymph nodes and extranodal sites, and 20% of ALCL and ALK- patients have involvement of both sites[3]. In patients with ALCL, the ALK+ subtypes are more often seen in the first three decades of life and, by definition,s carry a 2;5 [t(2;5)(p23;q35)] chromosomal translocation of the ALK gene resulting in overexpression of the ALK protein[4]. The ALK- subtype of ALCL usually occurs in middle age and has a worse prognosis[5]. An extranodal presentation is found in only 20% of the cases[6]. The most frequent extranodal involvement sites are the skin, lungs, bone, and liver[7,8], whereas the colon is rarely reported as being involved[3,9]. To the best of our knowledge, there have only been 9 such cases reported in 4 papers written in English[10-13]. Three of those reports were case reports, and no review has focused on this rare presentation. Therefore, in addition to reporting one case of ALCL, ALK- involving the colon and penis, we also conducted a literature review that showed some interesting clinical and pathological features of gastrointestinal ALCL, ALK-.

A 54-year-old male was admitted to the department of gastroenterology for abdominal pain. He presented with lower abdominal pain; frequent passing of stool, diarrhea and mucus; and recurrent oral ulcers.

The patient was a 54-year-old male with a history of a recurrent penile ulcer for 6 years. He presented with lower abdominal pain; frequent passing of stool, diarrhea and mucus; and recurrent oral ulcers. No additional sites of involvement were identified. CT enterography (CTE) and colonoscopy showed skip lesions and different sizes and shapes of ulcers in the colon. The lesions of the colon were biopsied for histological examination. The biopsy showed nonspecific ulcers of the colon. According to his history and auxiliary examinations, he was diagnosed with Behcet's disease (BD) and treated with prednisone. He was discharged in an improved condition. After one month, he was hospitalized in another hospital because of colon perforation. After operation, he was transferred to the rheumatology and immunology department. This time, bilateral inguinal lymph nodes were found enlarged. The lesion on the penis was biopsied for histological examination. The final pathological diagnosis was ALCL, ALK-negative (ALCL, ALK-).

No past illnesses were documented.

Unremarkable.

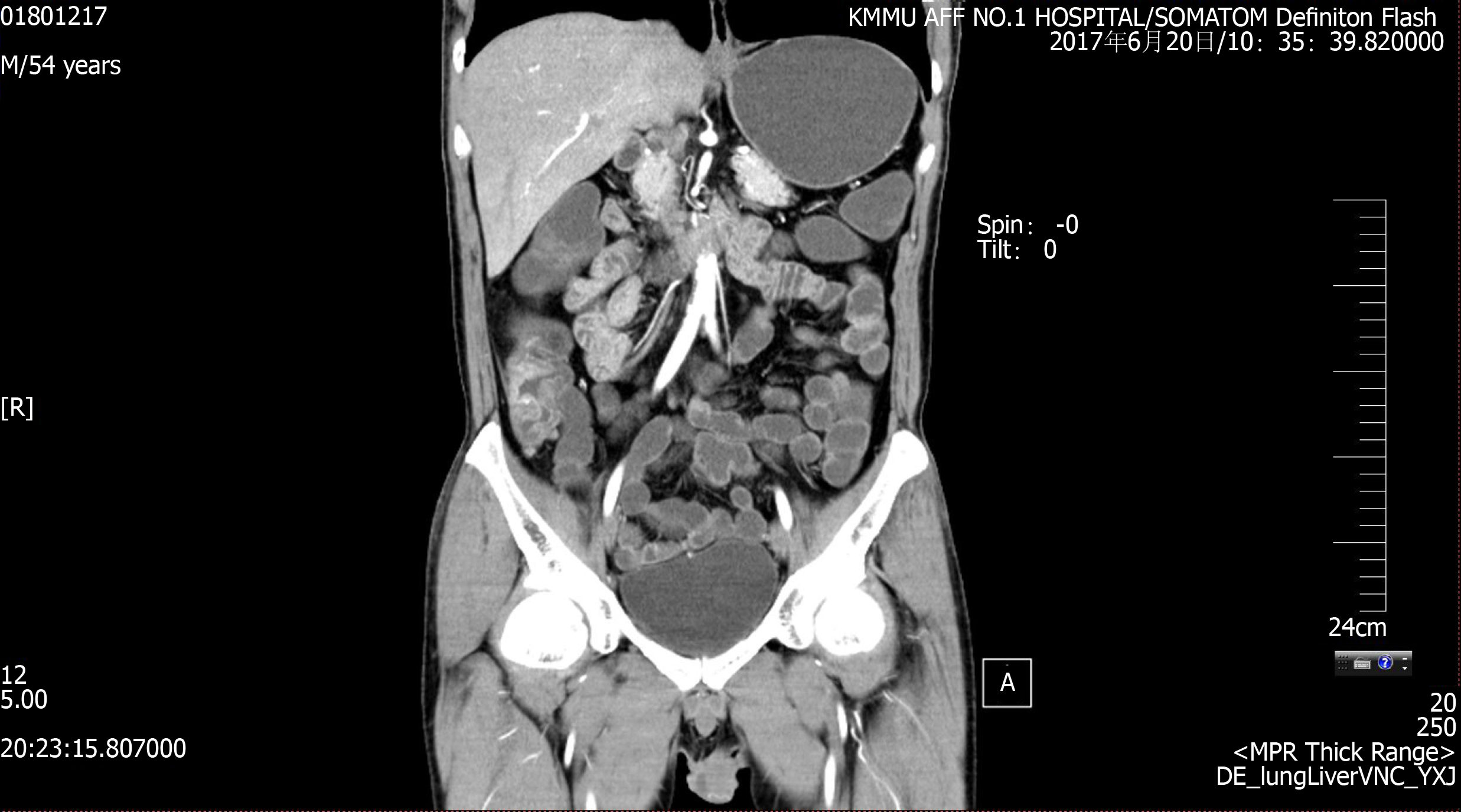

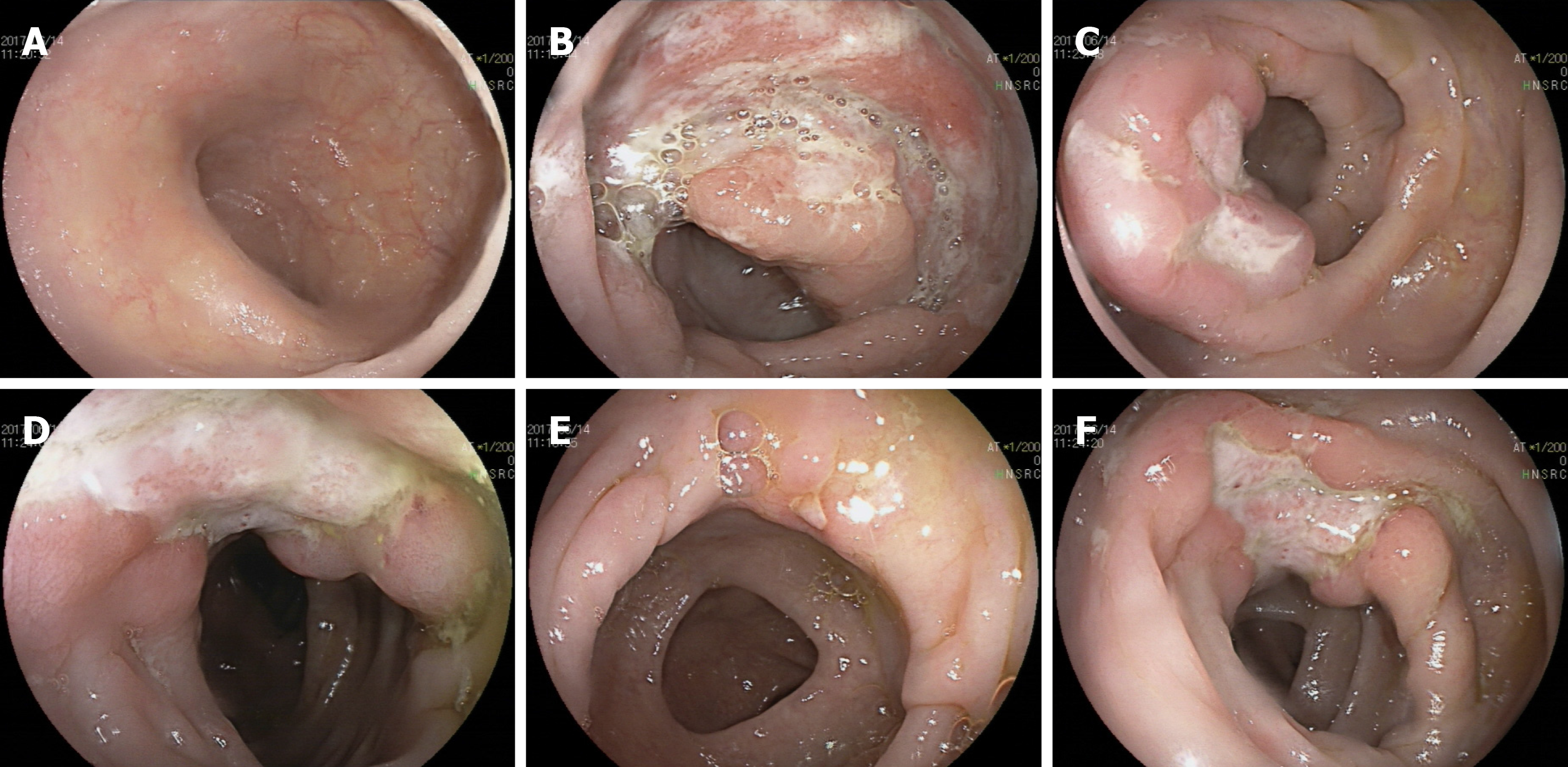

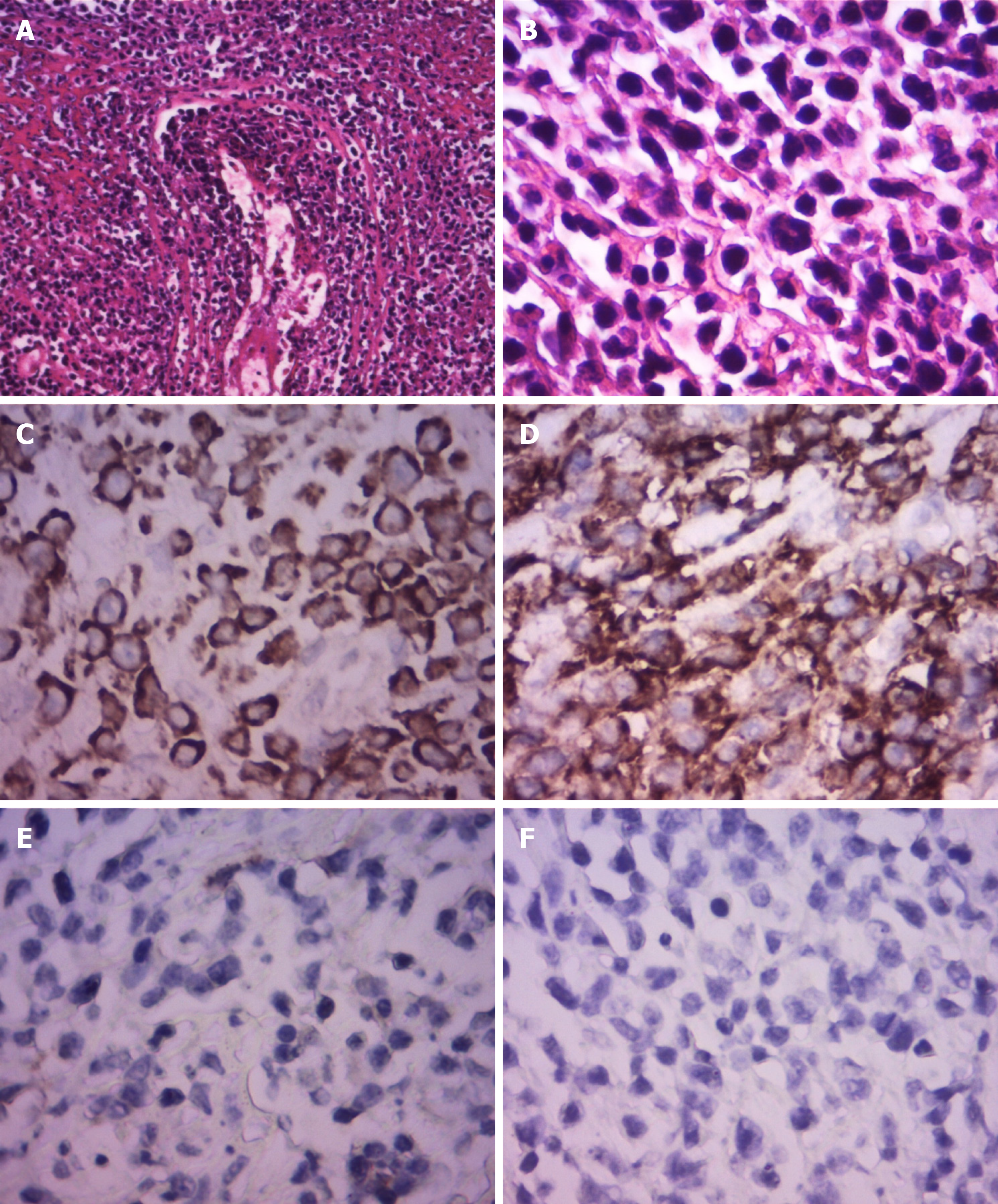

CT enterography (CTE) showed abnormal thickening of the bowel walls at the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, and descending colon, and the intestinal wall showed obvious enhancement in the arterial stage (Figure 1). Colonoscopy showed skip lesions and different sizes and shapes of ulcers in the cecum, transverse colon, and descending colon (Figure 2). The lesion on the penis was biopsied for histological examination. HE staining showed infiltration of large lymphoid cells (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry showed that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD2, CD3, CD10, CD30, LCA, and Mum-1. The expression of Ki-67 was 70% positive. The cells were negative for CD20, CD56, Bcl-2, Bcl-6, Pax-5, P40, P63, PCK, ALK-80, and EBER (Figure 3). The final pathological diagnosis was ALCL, ALK-negative (ALCL, ALK-).

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma at IVE.

The patient was treated with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone (CHOP) chemotherapy once.

However, the patient died of septic shock soon.

ALCL is a CD30+ positive T cell lymphoma with its own characteristic morphology and immunophenotype[14]. According to the expression of ALK, the WHO 2016 classification system divided ALCL into four entities: systemic ALK-positive ALCL (ALCL, ALK+), systemic ALK-negative ALCL (ALCL, ALK-), primary cutaneous ALCL (pC-ALCL), and breast implant-associated ALCL (BI-ALCL)[2]. ALCL, ALK- represents 15%-50% of the cases of systemic ALCL. While most cases of ALCL, ALK+ are seen in children, ALCL, ALK- is often found in adults[3]. ALCL, ALK+ is sensitive to chemotherapy and often has a better prognosis, but ALCL, ALK- always occurs in elderly patients with a poor clinical outcome[9]. ALCL, ALK- results in a worse prognosis than ALCL, ALK+, with 5-year survival rates of 50% and 70%, respectively[9,15]. ALCL, ALK- mainly involves the lymph nodes but approximately 20% of cases can also be found in extranodal sites[3]. Secondary involvement of ALCL, ALK- in the skin has to be distinguished from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas, including pC-ALCL and BD. The differential diagnosis is difficult and requires a comprehensive approach, including clinical evaluation, histopathologic evaluation, and determination of the immunophenotype[6]. The extranodal sites often include the skin, breast, lungs, bone, liver and gastrointestinal tract[3,9,16,17]. To the best of our knowledge, only one case reported pC-ALCL presenting as paraphimosis[18]. Our case is the second reported case of ALCL in the penis and the first one of systemic ALK-negative ALCL.

The incidence of primary intestinal lymphomas is very rare. Gastrointestinal lymphomas account for 20% of them, and most of them are mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas[19,20]. We present a case of primary ALCL arising in the oral cavity, penis, and colon, which was initially misdiagnosed as BD. In 2013, the International Study Group criteria for BD presents a new criteria that ocular lesions, oral aphthosis and genital aphthosis are each assigned 2 points, while skin lesions, central nervous system involvement and vascular manifestations 1 point each[21]. A patient scoring ≥ 4 points is classified as having BD. So this patient just fit the criteria. But finally, the morphologic and phenotypic features were found to be consistent with systemic ALCL, ALK-, at IVE. This may be because the presence of inflammation with neutrophil infiltration affects the mucosa in systemic ALCL[22]. Therefore, in our case, neutrophil infiltration may have been associated with the presence of large ulcers at multiple sites, as reported in Lapthanasupkul et al[23]. It is extremely rare for ALCL to initially present with gastrointestinal symptoms. Our review of the English language literature identified four papers that reported this disease, including nine case reports[10-12] (Table 1). Including the current case, the patients were eight males and two females (4:1). The median age was 66.3 years (ranging from 54 to 88 years). The main gastrointestinal sites involved were the esophagus in 1 case (10%), the stomach in 4 cases (40%), the jejunum in 1 case (10%), the terminal ileum in 2 cases (20%), and the colon in 2 cases (20%). The cases initially presented with abdominal pain, mass or diarrhea. Colonoscopy revealed a reddish ulcerative lesion with protrusion or different sizes and shapes of ulcers. After receiving six cycles of CHOP chemotherapy or other therapies, three patients achieved complete remission. The other seven patients died due to disease progression from 0.7 to 63 mo after the diagnosis.

| Ref. | Gender;Age | Presenting symptom; impression | Primary site | Biopsy or surgery | Perforation | Marrow involvement | Treatment | Follow-up |

| Sakakibara et al[10], 2015 | M 65 | A painful hard mass in the left buttock. | Ascending colon | Colon biopsy | (-) | (-) | Six cycles of CHOP | Achieved complete remission |

| Tian et al[11], 2016 | M 39 | Epigastric pain with low-grade fever | Stomach | Stomach biopsy | (-) | (-) | Four cycles of CHOP, then two cycles of Hyper-CVAD/MA | Died 3 mo later |

| Zhang et al[12], 2017 | M 82 | Weakness | Stomach | Stomach biopsy | (-) | (-) | Brentuximab | Clinically improved |

| Lee et al[13], 2017 | F 64 | Not mentioned | Oesophagus | Segmental resection of distal oesophagus and proximal partial gastrectomy | (-) | (-) | Various regimens and transplantation after relapse | Died 63 mo later |

| M 59 | Not mentioned | Stomach | Partial gastrectomy | (-) | (-) | CHOP | No evidence of disease after 81 mo | |

| F 70 | Epigastric pain with poor appetite | Stomach | Total gastrectomy and liver biopsy | (-) | CHOP and ESHAP | Died 21 mo later | ||

| M 65 | Fever | Jejunum | Segmental resection | (+) | (+) (focal) | Nil | Died 0.7 mo later | |

| M 88 | Not mentioned | Terminal ileum | Segmental resection | (-) | (-) | CHOP | Alive with disease after 4 mo | |

| M 37 | Not mentioned | Terminal ileum | Right hemicolectomy | (-) | Not done | Nil | Died 0.7 mo later | |

| Current study | M 54 | Lower abdominal pain and diarrhea | Colon | Penis biopsy | (+) | Not done | One cycle of CHOP | Died 1 mo later |

In summary, there are some interesting clinicopathologic features associated with the gastrointestinal involvement of ALCL: (1) There is a male predominance; (2) The majority of the patients are more than 50 years old; (3) The patients uniformly present with gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, mass or diarrhea; (4) The primary neoplasm is in the stomach; (5) Endoscopic examination often shows irregular ulcers; and (6) The most commonly used treatment is CHOP, but the prognosis is poor. Although limited by the number of cases available, our findings indicate that this group of ALCLs has an unusual clinical presentation and could pose a diagnostic challenge. Furthermore, a timely diagnosis and treatment are crucial to avoid disease progression. It is essential to establish a timely diagnosis of ALCL through pathological, immunohistological, and clinical evaluations[22]. We hope this review will bring attention to and help us understand the rare presentation of ALK-negative ALCL. In addition, gastrointestinal ALCL needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis even when autoimmune bowel disease is suspected, especially in older patients.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kohei S, Kupeli S S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Ma JY E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Bennani-Baiti N, Ansell S, Feldman AL. Adult systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: recommendations for diagnosis and management. Expert Rev Hematol. 2016;9:137-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz AD, Jaffe ES. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4245] [Cited by in RCA: 5395] [Article Influence: 599.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ferreri AJ, Govi S, Pileri SA, Savage KJ. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK-negative. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;85:206-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Morris SW, Kirstein MN, Valentine MB, Dittmer KG, Shapiro DN, Saltman DL, Look AT. Fusion of a kinase gene, ALK, to a nucleolar protein gene, NPM, in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Science. 1994;263:1281-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1698] [Cited by in RCA: 1704] [Article Influence: 55.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sabattini E, Bacci F, Sagramoso C, Pileri SA. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: an overview. Pathologica. 2010;102:83-87. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Montes-Mojarro IA, Steinhilber J, Bonzheim I, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Fend F. The Pathological Spectrum of Systemic Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL). Cancers (Basel). 2018;10:E107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Querfeld C, Khan I, Mahon B, Nelson BP, Rosen ST, Evens AM. Primary cutaneous and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma: clinicopathologic aspects and therapeutic options. Oncology (Williston Park). 2010;24:574-587. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Tsuyama N, Sakamoto K, Sakata S, Dobashi A, Takeuchi K. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma: pathology, genetics, and clinical aspects. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2017;57:120-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Savage KJ, Harris NL, Vose JM, Ullrich F, Jaffe ES, Connors JM, Rimsza L, Pileri SA, Chhanabhai M, Gascoyne RD, Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD; International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. ALK- anaplastic large-cell lymphoma is clinically and immunophenotypically different from both ALK+ ALCL and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: report from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Blood. 2008;111:5496-5504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 620] [Cited by in RCA: 612] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sakakibara Y, Nakazuru S, Yamada T, Iwasaki T, Iwasaki R, Ishihara A, Nishio K, Ishida H, Kodama Y, Mita E. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma with colon involvement. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29:345-346. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Tian C, Zhang Y. Primary gastric anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:5659-5661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang W, Burton S, Wu S, Qian X, Rajeh MN, Schroeder K, Shuldberg M, Merando A, Lai JP. Primary Gastric ALK-negative EBV-negative Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Presenting with Iron Deficiency Anemia. In Vivo. 2017;31:701-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee YY, Takata K, Wang RC, Yang SF, Chuang SS. Primary gastrointestinal anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Pathology. 2017;49:479-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang X, Wu J, Zhang M. Advances in the treatment and prognosis of anaplastic lymphoma kinase negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Hematology. 2019;24:440-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vose J, Armitage J, Weisenburger D; International T-Cell Lymphoma Project. International peripheral T-cell and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma study: pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4124-4130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1369] [Cited by in RCA: 1564] [Article Influence: 92.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xu X. ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma primarily involving the bronchus: a case report and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;7:460-463. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Tuck M, Lim J, Lucar J, Benator D. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma masquerading as osteomyelitis of the shoulder: an uncommon presentation. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016217317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | McNab PM, Jukic DM, Mills O, Browarsky I. Primary cutaneous CD30+ T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder presenting as paraphimosis: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:3. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Wong MT, Eu KW. Primary colorectal lymphomas. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:586-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Habr-Gama A, Campos FG, Ribeiro Júnior U, Gansl R, da Silva JH, Pinotti HW. [Primary lymphomas of the large intestine]. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 1993;48:272-277. [PubMed] |

| 21. | International Team for the Revision of the International Criteria for Behçet's Disease (ITR-ICBD). The International Criteria for Behçet's Disease (ICBD): a collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:338-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 670] [Cited by in RCA: 888] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sciallis AP, Law ME, Inwards DJ, McClure RF, Macon WR, Kurtin PJ, Dogan A, Feldman AL. Mucosal CD30-positive T-cell lymphoproliferations of the head and neck show a clinicopathologic spectrum similar to cutaneous CD30-positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:983-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lapthanasupkul P, Songkampol K, Boonsiriseth K, Kitkumthorn N. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the palate: A case report. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;120:172-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |