Published online Oct 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i20.3282

Peer-review started: May 21, 2019

First decision: July 30, 2019

Revised: August 30, 2019

Accepted: September 9, 2019

Article in press: September 9, 2019

Published online: October 26, 2019

Processing time: 162 Days and 10.7 Hours

Systemic amyloidosis in which multiple systems can be involved has become a common clinical disease. When the liver is affected, symptoms such as abdominal distension, fatigue, edema, liver, and jaundice could appear. To date, hepatic amyloidosis combined with hepatic venular occlusive disease and Budd-Chiari syndrome has not been reported.

A 54-year-old female patient was admitted to the Beijing Shijitan Hospital with hepatic amyloidosis leading to hepatic venular occlusion and Budd-Chiari syndrome in 2018. The patient underwent surgery 1 mo previously for liver rupture and hemorrhage after Budd-Chiari syndrome was diagnosed. She was diagnosed with hepatic venular occlusion, liver amyloidosis, and Budd-Chiari syndrome (i.e. extensive hepatic vein occlusion). Transjugular intrahepatic portosystem shunt was performed. After the treatment, the clinical symptoms improved markedly with increase in urine volume.

Hepatic amyloidosis with hepatic venous occlusion and Budd-Chiari syndrome is relatively rare clinically, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystem shunt is an effective treatment for this disease.

Core tip: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystem shunt is an effective treatment for hepatic amyloidosis with hepatic venous occlusion and Budd-Chiari syndrome.

- Citation: Li TT, Wu YF, Liu FQ, He FL. Hepatic amyloidosis leading to hepatic venular occlusive disease and Budd-Chiari syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(20): 3282-3288

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i20/3282.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i20.3282

Amyloidosis, a type of clinical syndrome, is caused by amyloid deposition in various organs, such as kidney, heart, liver, gastrointestinal tract, tongue, spleen, nervous system, and skin[1-6]. The affected organs are enlarged and dysfunctional. Hepatic amyloidosis, a part of systemic amyloidosis, is a metabolic disease caused by the extracellular amyloid deposits in the hepatic blood vessel walls and tissues[7]. Patients with hepatic amyloidosis may have the following symptoms: fatigue, weakness, weight loss, shortness of breath after fatigue, edema, and liver enlargement[8]. Hepatic venous occlusion (HVOD), also known as sinus space obstruction syndrome, is a non-thrombotic obstruction of hepatic circulation that is accompanied by lobular central sinus space fibrosis and common hepatic venular fibrosis stenosis or occlusion[9-10]. Clinical symptoms of HVOD include liver enlargement, pain, and ascites. It was reported that more than 50% of patients showed recovery, 20% died of liver failure, and a few patients developed cirrhotic portal hypertension. Budd-Chiari syndrome is a type of retrohepatic portal hypertension caused by hepatic vein and inferior vena cava obstruction above the opening of the hepatic vein[11-13]. Hepatic amyloidosis along with HVOD and Budd-Chiari syndrome is relatively rare clinically; therefore, no study has been reported to date. We here report a patient who was admitted to our hospital with hepatic amyloidosis complicated with HVOD and Budd-Chiari syndrome.

A 54-year-old female patient developed persistent severe pain in the upper abdomen after abdominal trauma combined with general weakness. After admission to a local hospital, she was diagnosed with abdominal hemorrhage with hemorrhagic shock, and emergency laparotomy was performed. During the operation, the liver was found to be enlarged diffusely, and a significant amount of non-coagulant blood was in the abdominal cavity. The right hepatic capsule was ruptured, and there was a large hematoma in the left liver. Liver biopsy was not performed, and the abdomen was closed after placing the abdominal drainage tube. Hemorrhagic ascites outflow continued after the operation. As the patient was in a critical condition, she was transferred to a superior hospital 2 d after the operation. After completing the relevant examinations, the patient was diagnosed with Budd-Chiari syndrome (a type of HVOD), portal hypertension, varicose esophageal veins, and gastric fundus veins. For further treatment, the patient came to our hospital. She had no history of other diseases.

Physical examinations showed temperature: 36.5 °C; pulse rate: 80 times/min; breathing rate: 16 times/min; and blood pressure: 120/80 mmHg. The patient had a poor general condition, emaciated, and weak with severe jaundice on the skin and mucous membranes; however, there were no liver palms or spider moles. Cardiopulmonary examination did not show any obvious abnormality. Abdominal swelling was present. There were no varicose veins in the abdominal wall. There was no obvious tenderness, rebound pain, and muscle tension, and the liver could be touched. Intestinal sound was 4 times/min, and both lower limbs had mild edema.

Laboratory tests revealed the following: White blood cell count: 11.97 × 109/L; routine urinalysis: Bilirubin 2 +, urine protein 3 +; Sed occult blood (-); blood biochemistry: ALT29U/L, AST74U/L, TBIL27 (1.4 µmol/L), DBIL (148.3 µmol/L), ALB (33.9 g/L), BUN (4.91 mmol/L), Cr (29 µmol/L); coagulation: PT15.3S, PTA (61%), INR (1.38); blood ammonia (45.2 µmol/L); HBsAg (-), HBsAb (+); CA125: 202.1; antibodies against autoimmune liver disease (-).

No abnormalities were observed on both chest radiography and electrocardiography.

Hepatic vascular ultrasound revealed that the inferior vena cava of the hepatic segment was compressed and narrowed by the enlarged hepatic tissue. The blood flow was unobstructed, and the three hepatic veins were not visible. The main portal vein and its intrahepatic branches were unobstructed.

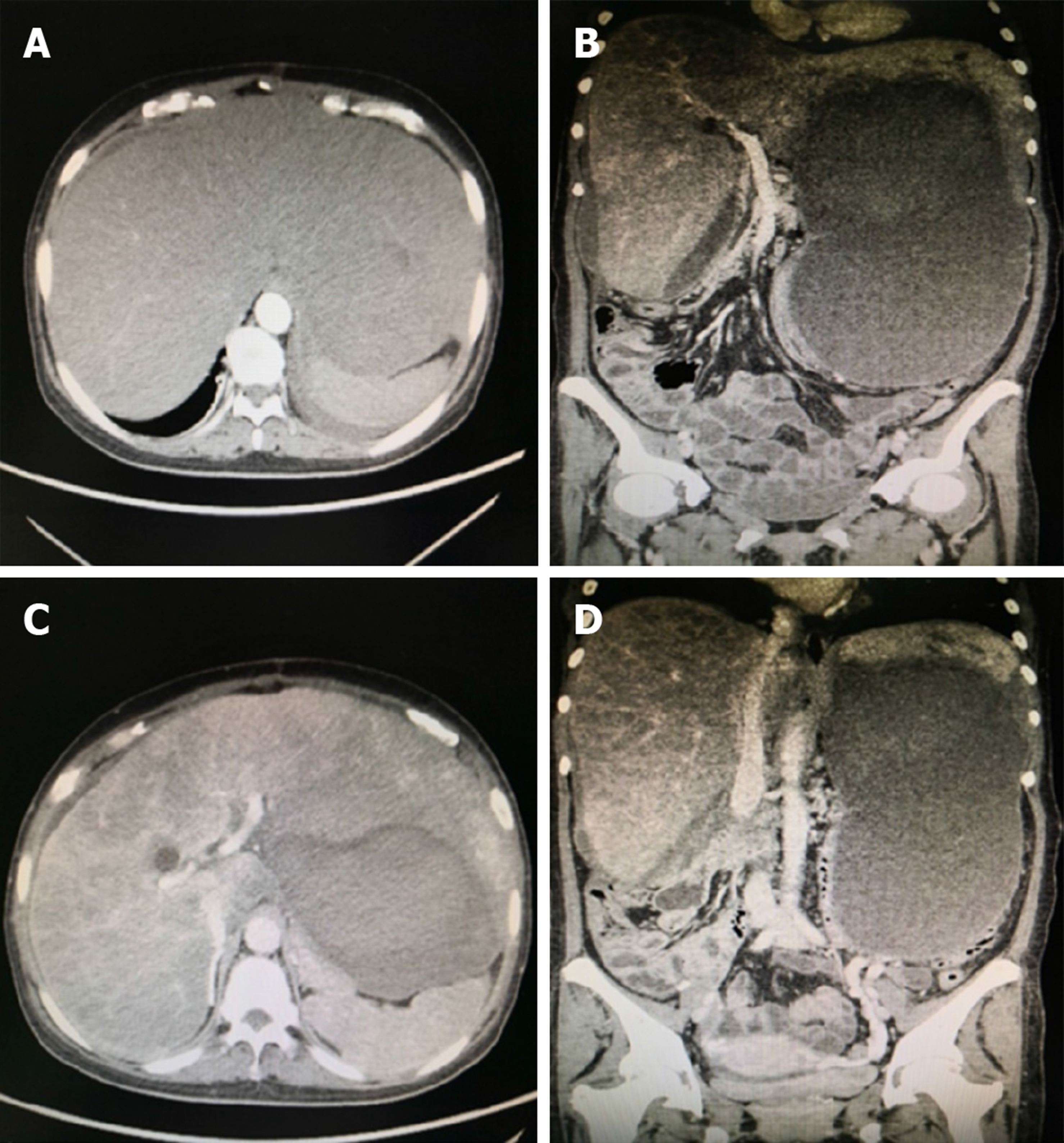

Abdominal computed tomography showed that the inferior vena cava of the hepatic segment was narrowed. The left, middle, and right hepatic veins were not clearly visible. The main portal vein and its branches were unobstructed (Figure 1).

Budd-Chiari syndrome, portal hypertension, ascites, varicose esophageal veins, and gastric fundus veins.

The patient was advised to have a good rest, avoid overwork, reduce the intake of liver damaging substances, and avoid the intake of hard food. Moreover, appropriate nutritional supplements were provided.

Polyene phosphatidylcholine, reduced glutathione dose for injection, and human serum albumin were administered.

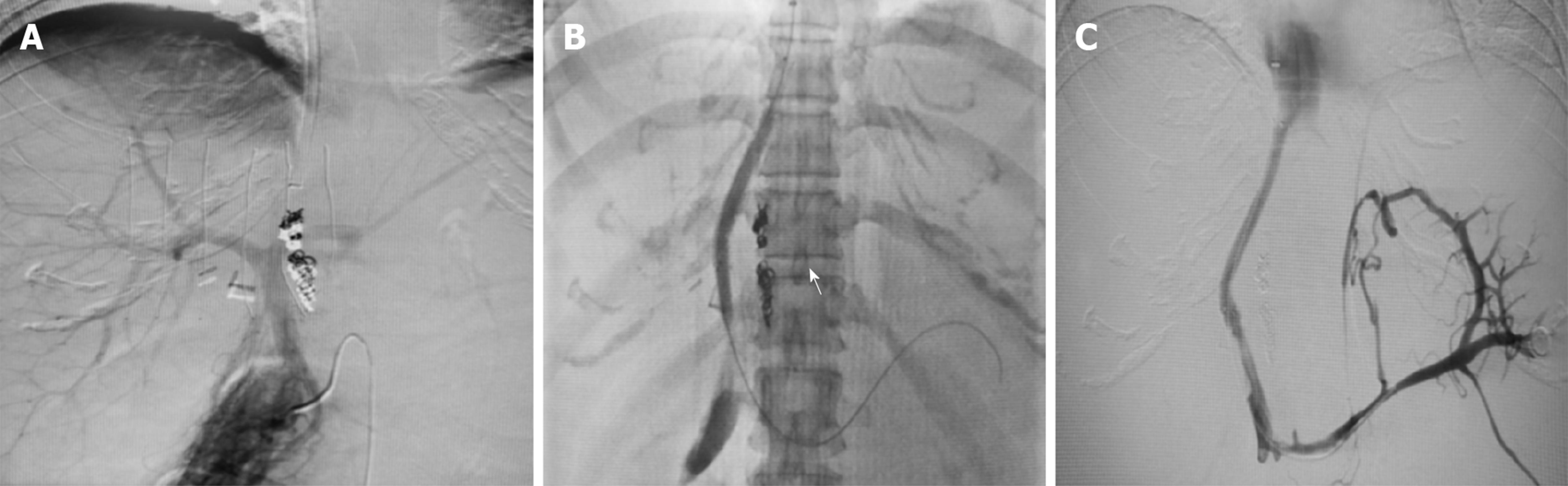

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystem shunt (TIPS) was performed. The right femoral artery and right internal jugular vein were punctured under local anesthesia, and inferior vena cava and hepatic venography was performed after catheterization. There was no thrombosis in the main portal vein and its intrahepatic branches. The inferior vena cava through the hepatic segment was narrowed. There was blood flow in the inferior vena cava of the hepatic segment, but the three hepatic veins were not shown. A thick accessory hepatic vein drained into the inferior vena cava through the third portal hepatis. The RUPS-100 was successfully punctured into the portal vein through the inferior vena cava. Under the guidance of a guidewire, a balloon (5 mm × 40 mm) was placed to predilate the puncture channel between the inferior vena cava and the portal vein. Two stents (8 mm × 60 mm, 7 mm × 60 mm) were placed between the puncture channels, and the good position of the stents was observed using fluoroscopy. During reexamination, it was observed that the contrast agent entered the inferior vena cava through the stents and the systemic circulation (Figure 2).

Intraoperative liver biopsy was performed through internal jugular vein. The results showed that while the hepatic sinus was blocked, the liver plate was atrophied and thin. Large areas of pink stains were seen, which were considered as amyloidosis. They were diagnosed as HVOD and hepatic amyloidosis. HVOD was most likely caused by hepatic amyloidosis.

Five days after TIPS, abdominal distension was reduced, the urine volume was significantly increased and the liver pain disappeared. There was no nausea, vomiting, or any other discomfort.

Hepatic vascular ultrasound showed that the stent was unobstructed, and the degree of liver swelling was less than before. The inferior vena cava of the hepatic segment was mildly expanded, and the three hepatic veins were not seen. There was no thrombosis in the main portal vein and its intrahepatic branches.

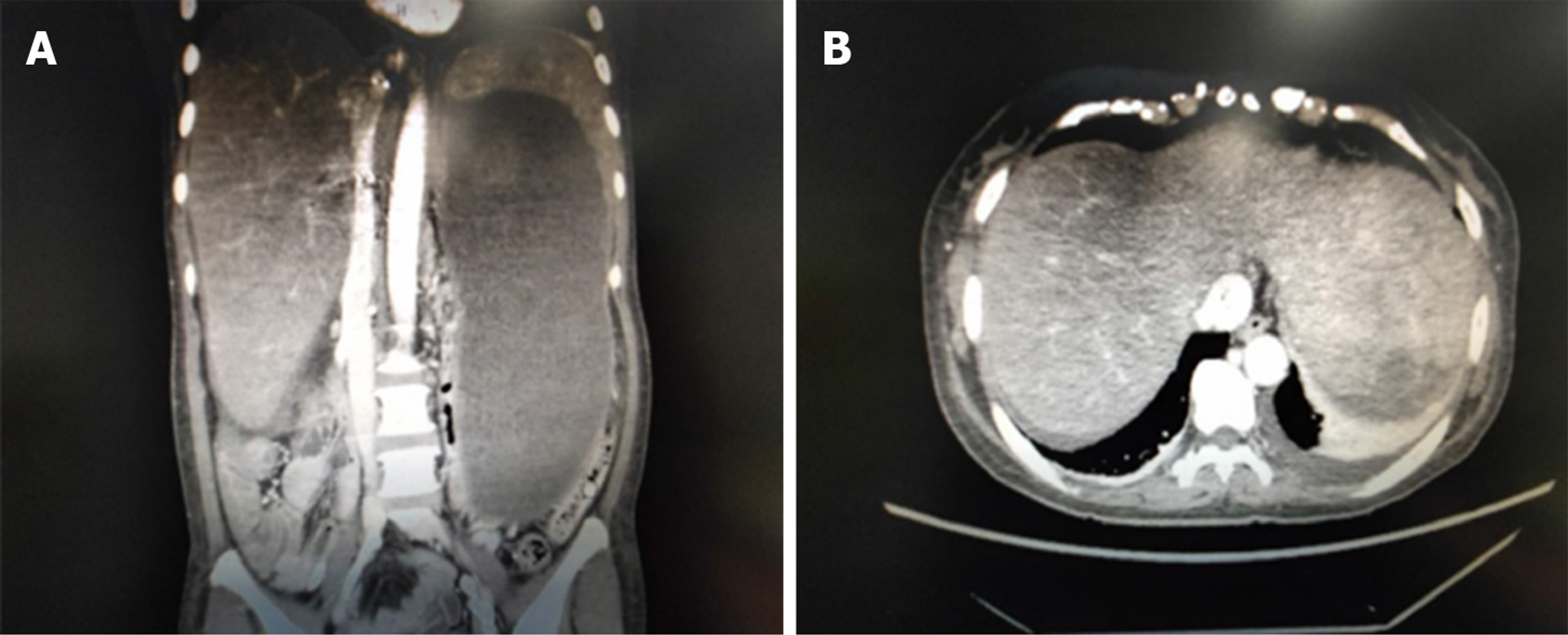

Abdominal computed tomography revealed that the stent was unobstructed, and the degree of liver swelling was less than before. The inferior vena cava of the hepatic segment expanded mildly, and the three hepatic veins were not seen (Figure 3).

Three months after TIPS, abdominal distension was reduced, the urine volume was significantly increased, and the liver pain disappeared.

Hepatic vascular ultrasound showed that the stent was unobstructed and the degree of liver swelling was obviously less than before. The inferior vena cava of the hepatic segment was expanded obviously. The three hepatic veins could not be seen. There was no thrombosis in the main portal vein and its intrahepatic branches.

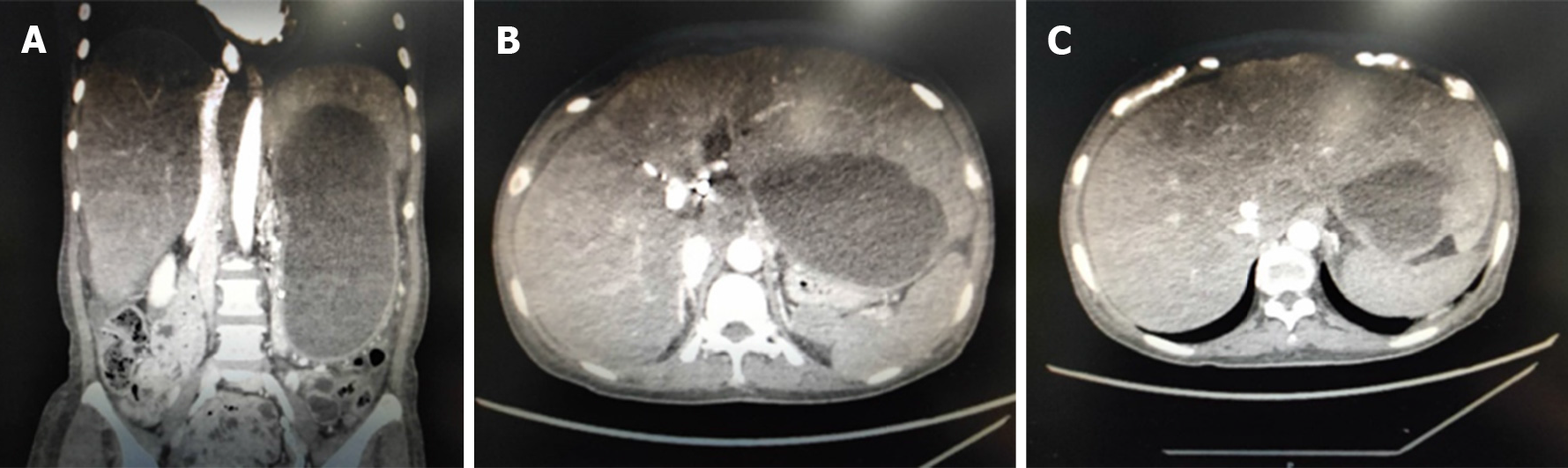

Abdominal computed tomography revealed that the stent was unobstructed and the degree of liver swelling was obviously less than before. The inferior vena cava of the hepatic segment was markedly expanded and the three hepatic veins were not seen (Figure 4).

Hepatic amyloidosis, a part of systemic amyloidosis, is a metabolic disease caused by extracellular amyloid deposits in the hepatic vascular walls and tissues. Although the etiology of primary hepatic amyloidosis is unknown, secondary amyloidosis is often induced by chronic diseases. Hepatic amyloidosis shows a clear and amorphous extracellular deposition that is mostly seen in the arterial and arteriolar wall and to a lesser extent in the portal vein and hepatic vein. The clinical manifestation of hepatic amyloidosis can be classified into three aspects[14]: (A) General performance: Abdominal distension, early fullness, weight loss, fatigue, and edema; (B) Extrahepatic amyloidosis syndrome: Nephrotic syndrome, congestive heart failure, postural hypotension, peripheral neuropathy, and carpal tunnel syndrome; and (C) liver involvement: liver enlargement, jaundice, and ascites.

HVOD refers to an injury of the central vein of the hepatic lobule and the sublobular vein of the patient. This leads to the narrowing or occlusion of the lumen of the central lobular vein and the inferior lobular vein, causing the symptoms of post-hepatic sinusoid portal hypertension[15]. Hepatic sinus endothelial cell injury results in an obstruction of the hepatic sinus outflow tract. The pathogenesis of HVOD is unclear. It may be associated with certain clinical treatments (hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and chemoradiotherapy) and the consumption of plants containing pyrrolidine alkaloids. Liver biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of this disease. The hepatic sinus was obviously dilated and filled with blood. The liver cells were swollen, degenerated, and necrotic to different degrees. The endothelium of the hepatic venules was swollen, degenerated, and shed. The fibrous tissue of the vessel wall was proliferated and degenerated, and stenosis was observed to different degrees. Clinical manifestations include liver enlargement, liver pain, jaundice, ascites, abdominal distension, and other symptoms.

Hepatic amyloidosis, HVOD, and Budd-Chiari syndrome are common clinically; however, hepatic amyloidosis combined with HVOD and Budd-Chiari syndrome is rare, and there are no relevant reports at present. In this report, we present a case of Budd-Chiari syndrome combined with HVOD caused by hepatic amyloidosis. From an imaging perspective, the patient’s liver was large and congested with uneven enhancement. The inferior vena cava of the hepatic segment was narrow with unclear development of the three hepatic veins. Initially, the Budd-Chiari syndrome was considered based on the patient’s imaging and symptoms. According to liver biopsy and laboratory tests, the patient was diagnosed with hepatic amyloidosis and hepatic venular occlusion. Considering the pathogenesis of the disease, hepatic amyloidosis may cause HVOD, which may further lead to Budd-Chiari syndrome. For the treatment, TIPS showed a good effect, which shunted the blood in the portal vein directly into the inferior vena cava. Moreover, it effectively alleviated the state of hepatic congestion and the clinical symptoms of the patient. After TIPS, the urine volume of the patient significantly increased, and the abdominal distension disappeared.

Systemic amyloidosis, a common clinical disease, can lead to hepatic amyloidosis when it involves the liver. Hepatic amyloidosis can cause hepatic venular occlusion, which further leads to Budd-Chiari syndrome. TIPS is an effective procedure for this disease.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Arville B, Shimizu Y S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Pinney JH, Smith CJ, Taube JB, Lachmann HJ, Venner CP, Gibbs SD, Dungu J, Banypersad SM, Wechalekar AD, Whelan CJ, Hawkins PN, Gillmore JD. Systemic amyloidosis in England: an epidemiological study. Br J Haematol. 2013;161:525-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mahmood S, Palladini G, Sanchorawala V, Wechalekar A. Update on treatment of light chain amyloidosis. Haematologica. 2014;99:209-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Takayasu V, Laborda LS, Bernardelli R, Pinesi HT, Silva MP, Chiavelli V, Simões AB, Felipe-Silva A. Amyloidosis: an unusual cause of portal hypertension. Autops Case Rep. 2016;6:9-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sonthalia N, Jain S, Pawar S, Zanwar V, Surude R, Rathi PM. Primary hepatic amyloidosis: A case report and review of literature. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:340-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Loudin M, Childers R, Zivony A, Lanciault C, Chang M, Ahn J. Liver Failure Secondary to Amyloid Light-Chain Amyloidosis. Am J Med. 2016;129:e19-e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pinney JH, Whelan CJ, Petrie A, Dungu J, Banypersad SM, Sattianayagam P, Wechalekar A, Gibbs SD, Venner CP, Wassef N, McCarthy CA, Gilbertson JA, Rowczenio D, Hawkins PN, Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ. Senile systemic amyloidosis: clinical features at presentation and outcome. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Krupa Ł, Staroń R, Pająk J, Lammert F, Krawczyk M, Gutkowski K. Secondary systemic amyloidosis diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided liver biopsy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2018;27:101-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Matsuda S, Motosugi U, Kato R, Muraoka M, Suzuki Y, Sato M, Shindo K, Nakayama Y, Inoue T, Maekawa S, Sakamoto M, Enomoto N. Hepatic Amyloidosis with an Extremely High Stiffness Value on Magnetic Resonance Elastography. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2016;15:251-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gao H, Li N, Wang JY, Zhang SC, Lin G. Definitive diagnosis of hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome induced by pyrrolizidine alkaloids. J Dig Dis. 2012;13:33-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pai RK, van Besien K, Hart J, Artz AS, O'Donnell PH. Clinicopathologic features of late-onset veno-occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstruction syndrome after high dose intravenous busulfan and hematopoietic cell transplant. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:1552-1557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Khan F, Mehrzad H, Tripathi D. Timing of Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Stent-shunt in Budd-Chiari Syndrome: A UK Hepatologist's Perspective. J Transl Int Med. 2018;6:97-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Martens P, Nevens F. Budd-Chiari syndrome. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:489-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhang W, Wang QZ, Chen XW, Zhong HS, Zhang XT, Chen XD, Xu K. Budd-Chiari syndrome in China: A 30-year retrospective study on survival from a single center. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1134-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yoshida S, Shimada M, Nishino T, Hiroshima K. Education and imaging. Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic: Elastography assessment in AL hepatic amyloidosis with no fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yang M, Ruan J, Gao H, Li N, Ma J, Xue J, Ye Y, Fu PP, Wang J, Lin G. First evidence of pyrrolizidine alkaloid N-oxide-induced hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome in humans. Arch Toxicol. 2017;91:3913-3925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |