Published online Jan 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i2.228

Peer-review started: October 2, 2018

First decision: November 1, 2018

Revised: November 12, 2018

Accepted: December 14, 2018

Article in press: December 15, 2018

Published online: January 26, 2019

Processing time: 117 Days and 22 Hours

Invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (IFR) caused by Cunninghamella is very rare but has an extremely high fatality rate. There have been only seven cases of IFR caused by Cunninghamella reported in English and, of these, only three patients survived. In this article, we present another case of IFR caused by Cunninghamella, in which the patient was initially treated successfully but then deteriorated due to a relapse of leukemia 2 mo later.

A 50-year-old woman presented with a 2-mo history of right ocular proptosis, blurred vision, rhinorrhea and nasal obstruction. Nasal endoscopic examination showed that the middle turbinate had become necrotic and fragile. Endoscopic sinus surgery and enucleation of the right orbital contents were performed successively. Additionally, the patient was treated with amphotericin B both systematically and topically. Secretion cultivation of the right eye canthus showed infection with Cunninghamella, while postoperative pathology also revealed fungal infection. The patient’s condition gradually stabilized after surgery. However, the patient underwent chemotherapy again due to a relapse of leukemia 2 mo later. Unfortunately, her leukocyte count decreased dramatically, leading to a fatal lung infection and hemoptysis.

Aggressive surgical debridements, followed by antifungal drug treatment both systematically and topically, are the most important fundamental treatments for IFR.

Core tip: Invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (IFR) caused by Cunninghamella is very rare but has an extremely high fatality rate. There have been only seven cases of IFR caused by Cunninghamella reported in English and, of these, only three patients survived. The middle turbinate has been found to be the most common site of invasion, followed by the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses. Antifungal drug treatment and/or surgical treatments are the most important fundamental treatments. In this article, we present another case of IFR caused by Cunninghamella, in which the patient was initially treated successfully but then deteriorated due to a relapse of leukemia 2 mo later.

- Citation: Liu YC, Zhou ML, Cheng KJ, Zhou SH, Wen X, Chang CD. Successful treatment of invasive fungal rhinosinusitis caused by Cunninghamella: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(2): 228-235

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i2/228.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i2.228

Invasive fungal disease (IFD) usually occurs in immunocompromised populations, such as patients with leukemia or undergoing transplants of hematopoietic cells, the intestine, lung, or liver; it is rare in immunocompetent populations. IFD has been associated with many factors, such as prolonged immunosuppression, pulses of corticosteroids, chronic graft dysfunction, previous use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, neutropenia, cytomegalovirus infection, diabetes, and advanced age[1]. Among patients with hematologic disease, those with acute leukemia are at the highest risk of developing IFD[2]. The mortality rate of patients with IFD is significantly higher than that of patients without IFD[3].

In leukemia patients, many types of fungi can cause IFD, such as Mucorales, Aspergillus, Candida, Fusarium, Alternaria, Penicillium, Acremonium, and Saccharomyces. Invasive infection with Cunninghamella is uncommon. Cunninghamella species are fungi belonging to the class Zygomycetes and the order Mucorales[4]. In healthy hosts, this fungal organism has a low potential for virulence[4]. Leukemia may decrease host immunity and increase the risk of invasive infection with Cunninghamella[5]. Cunninghamella occurring in leukemia patients classically follows a pattern of pulmonary infection by inhalation of aerosolized spores and dissemination to other organs[6]. It can be divided into several types: rhinocerebral, pulmonary, cutaneous, gastrointestinal, or disseminated infections[7]. The prognosis of this disease is poor even with treatment, and the mortality rate is high[8]. In this article, we present another case of invasive fungal rhinosinusitis (IFR) caused by Cunninghamella, in which the patient was successfully treated at first but then deteriorated during subsequent chemotherapy, to illustrate this lethal disease.

A 50-year-old female patient presented to our otolaryngological ward complaining of right ocular proptosis, distending pain, blurred vision, epiphora, bilateral nasal obstruction, and rhinorrhea for about 2 mo.

Four months earlier, the patient was hospitalized in the hematology ward with a diagnosis of acute myeloid leukemia and treated with chemotherapy for three cycles. Two months earlier, the patient complained of right ocular proptosis, distending pain, blurred vision, epiphora, bilateral nasal obstruction, and rhinorrhea after the second cycle of chemotherapy, with a leukocyte count of 0.4 × 10-9/L and neutrophils at 2.7%. The symptoms did not improve after treatment with an antibiotic and glucocorticoid; the right ocular proptosis was aggravated and the eyesight in the right eye gradually decreased to the point of blindness.

Nasal examination showed slight edema of the nasal mucosa, slight hypertrophy of the bilateral inferior turbinates, and a partial defect of the mucous membrane of the right middle turbinate. Ocular examination showed right ocular proptosis, difficulty of eye opening, multi-direction activity limitation, chemosis, blindness, and blackening of the skin of the inner canthus.

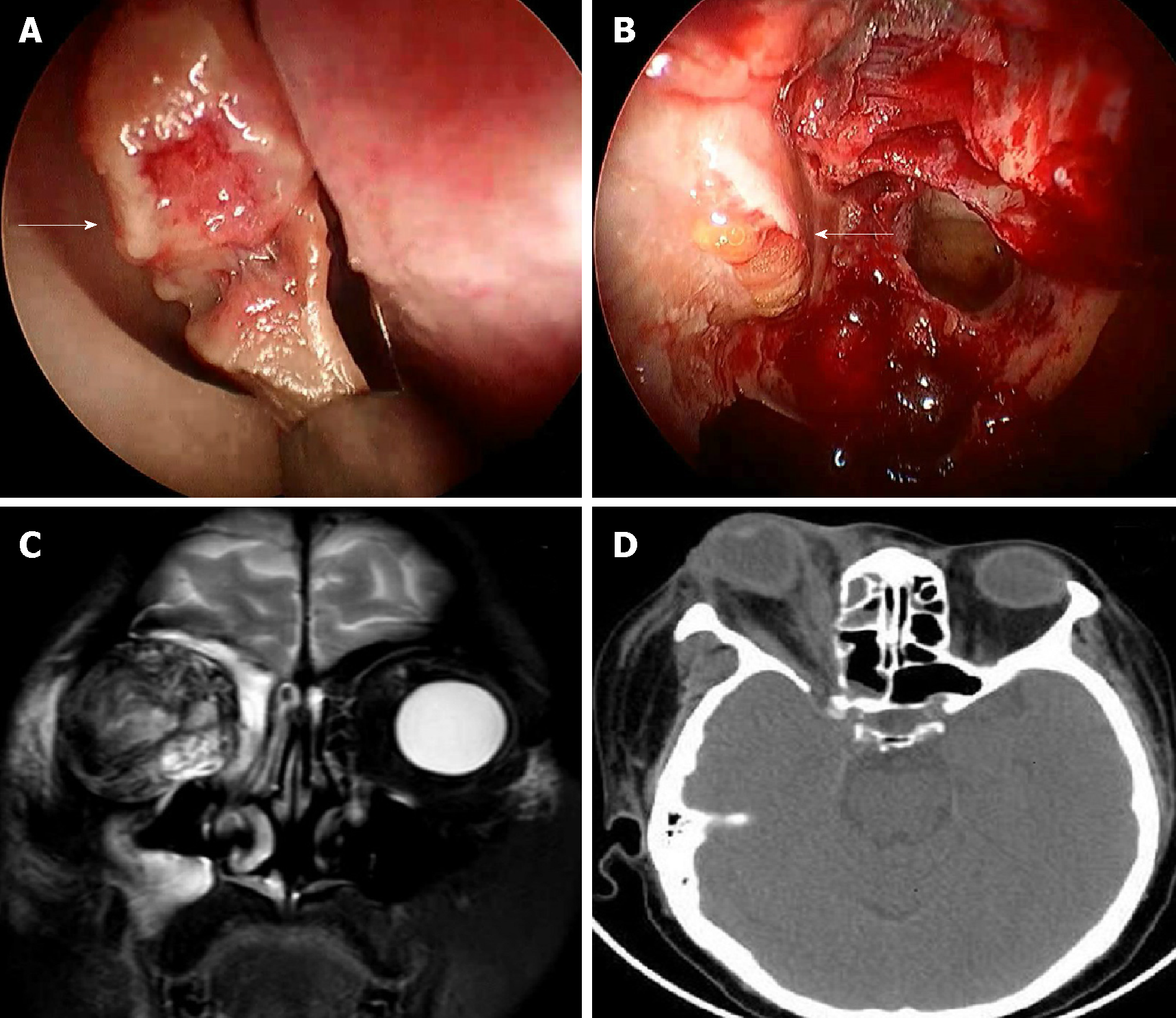

Routine blood tests indicated an elevation of the leukocyte count to 15.5 × 10-9/L, and of neutrophils to 93.3%. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the sinuses revealed inflammation of the bilateral maxillary and ethmoid sinuses, and the right frontal and sphenoid sinuses. The bones of the sinus walls were not affected. The CT scan also revealed right ocular proptosis, blurring of intraorbital fat, and thickening of extraocular muscles. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed thickening of the right extraocular muscles with a high signal on T2-weighted images. The right eyeball was pressed and distorted, but there was no obvious abnormality within the left orbit (Figure 1).

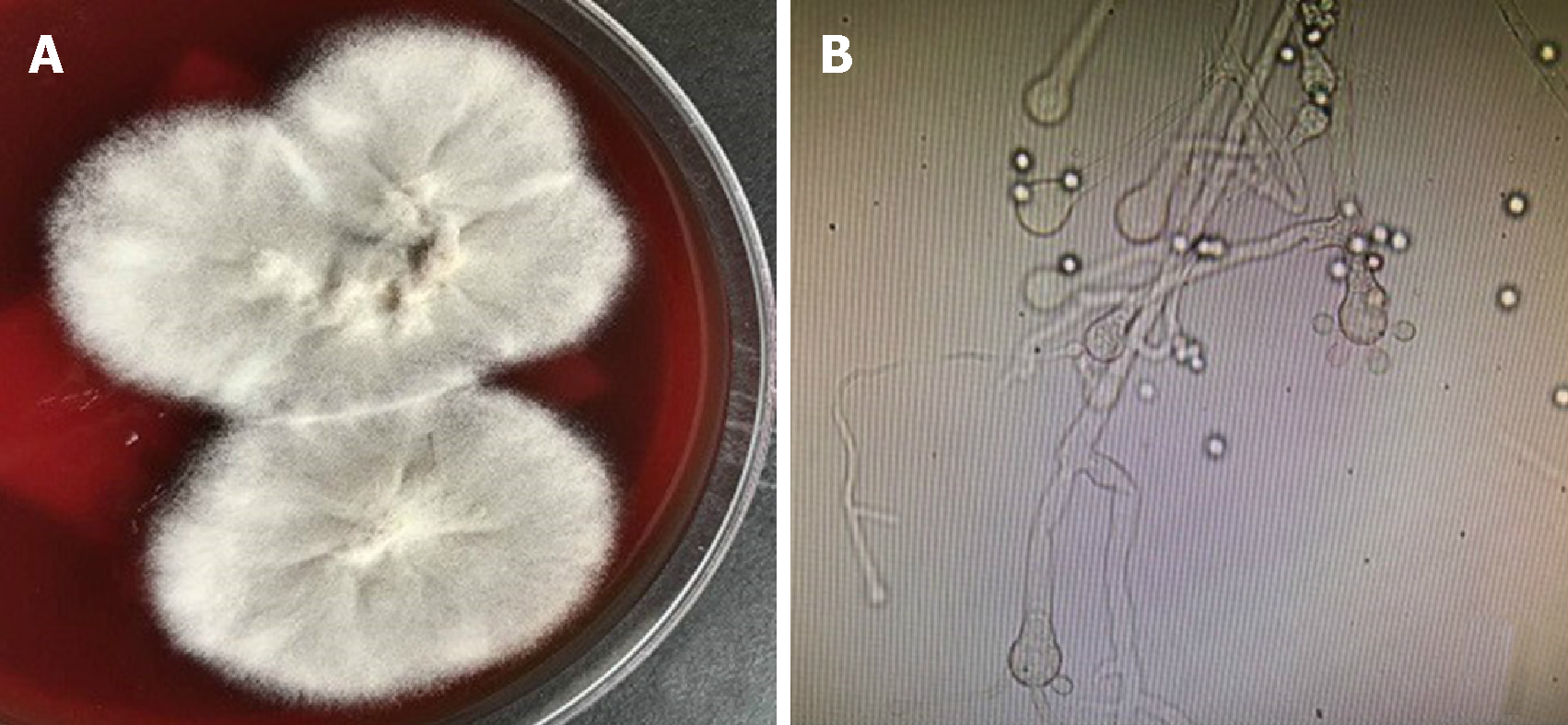

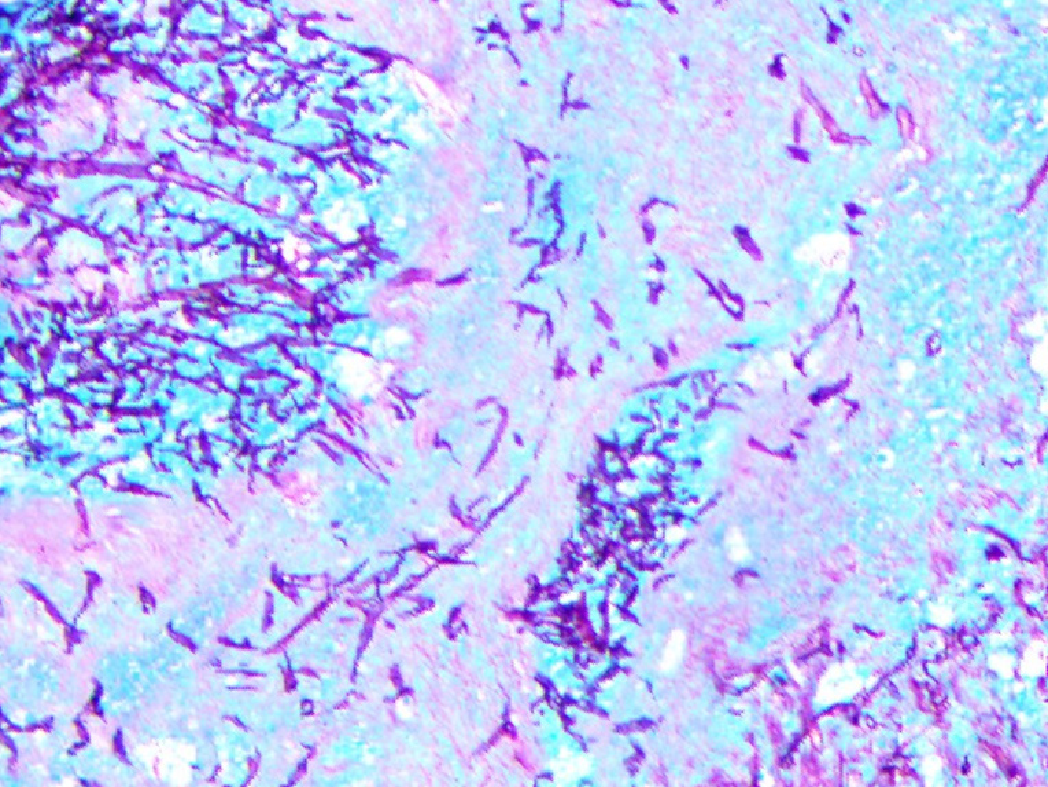

Secretion cultivation of the right eye canthus showed infection with Cunninghamella (Figure 2), and postoperative pathology revealed a large quantity of fungus mycelia and spores within the necrotic tissue of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinus (Figure 3).

We performed endoscopic sinus surgery and right orbit decompression surgery under general anesthesia (Figure 1). The nasal septum deviated slightly toward the right side and there was a partial mucous membrane defect of the right middle turbinate. We resected part of the right middle turbinate and opened the right maxillary and ethmoid sinus during the operation. We found abundant dark-red blood clots and necrotic tissue in the right maxillary sinus. The mucous membrane of the right ethmoid sinus showed partial avascular necrosis, and the mucous membrane of the posterior ethmoid sinus had partly blackened. We resected a large proportion of the right orbital lamina. The orbital fascia was distended toward the ethmoid sinus, and the orbital fascia was also resected. The right uniform process, a mass in the right maxillary sinus, the right middle turbinate, the mucous membrane of the posterior ethmoid sinus, and the intraorbital fat were inspected in a further pathological examination.

After the surgery, the patient was treated with amphotericin B, meropenem, metronidazole, tigecycline, and posaconazole. Secretion cultivation of the right eye canthus showed infection with Cunninghamella, and postoperative pathology revealed a large quantity of fungus mycelia and spores within the necrotic tissue of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinus. Then amphotericin B irrigation (amphotericin B 20 mg, NS 250 mL, bid) was applied in the nasal cavity, and amphotericin B eye drops (amphotericin B 25 mg, 5% GNS 16 mL, 2–5 drops/30 min) were also administered. Ten days after the nasal surgery, an extremely serious infection of the right orbit occurred and an ophthalmologist performed an enucleation of the right orbital contents. Postoperative pathology of the right eyeball also revealed fungal infection. After the second surgery, the patient was treated with amphotericin B, voriconazole, and piperacillin/tazobactam. Dressing changes of the right orbit and amphotericin B nasal irrigation were done every day.

The patient’s condition was gradually stabilized. Endoscopic examination showed that the patient was recovering well after the nasal surgery. However, 2 mo after the second surgery, the patient’s bone marrow examination showed leukemia relapse. She was treated with chemotherapy again and CT examination showed mycotic infection of the right lung. The patient was then treated with posaconazole, amphotericin B, caspofungin, tigecycline, and sulperazone, but her condition deteriorated until finally hemoptysis led to her death.

The reported incidence of IFD in patients with leukemia ranges from 2% to 15%[9]. IFD remains a common cause of morbidity and mortality among patients with leukemia; it is mainly caused by Candida and Aspergillus species[10]. IFD caused by Cunninghamella in patients with acute leukemia is extremely rare. However, this kind of IFD usually appears as a disseminated type and has a very poor prognosis. Su et al[11] reported a disseminated Cunninghamella infection in a girl with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, who ultimately died of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Strasfeld et al[12] presented three cases of invasive Cunninghamella infection in allogeneic transplant recipients: two of the disseminated type and one pulmonary type. All patients died shortly after the confirmation of invasive Cunninghamella infection[12]. We searched the PubMed database for reports of IFD caused by Cunninghamella, presenting as the rhinocerebral type, for the period 1980 to 2017 and found cases in English-language articles that included clinical details.

To our knowledge, there have been only eight cases (including the present case) of IFD, caused by Cunninghamella and presenting as the rhinocerebral type, reported in English (Table 1)[13-19]. Among them, there were six males and two females. The male-to-female ratio was 3:1. The patients ranged in age from 15 to 70 years, with a mean age of 50.9 years. In this review, three patients lived in the United States, and the other five lived in Thailand, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Italy, and China, respectively. Seven (87.5%) patients had underlying conditions and only one (12.5%) patient had no accompanying disease. Among them, four (50%) patients had acute leukemia (two AML, one acute promyelocytic leukemia, and one mixed lineage T-cell and myeloid acute leukemia), three (37.5%) had diabetes mellitus, one (12.5%) had bone marrow transplantation, one (12.5%) had myelodysplasia, and one (12.5%) had sideroblastic anemia and hemochromatosis.

| Ref. | Sex/age | Region | Underlying conditions | Symptoms | Site(s) of involvement | Drug treatment | Surgery | Outcome |

| Brennan et al[13], 1983 | M/70 | United States | Diabetes mellitus, sideroblastic anemia, hemochromatosis | Facial pain and palsy, periorbital swelling, hearing loss, visual loss, fever, mental confusion | Nasal sinuses, orbit, brain | Amphotericin B | Orbital decompression, sinus surgery | Died |

| Chetchotisakd et al[14], 1991 | F/68 | Thailand | Diabetes mellitus | Headache, left eye pain | Nasal sinuses | Amphotericin B, 5-flucytosine | Sinus surgery | Survived |

| Kontoyiani et al[15], 1994 | M/51 | United States | Acute promyelocytic leukemia | Fever, nasal obstruction, dyspnea, fatigue, | Nasal sinuses, lung | Imipenem, vancomycin, trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole, fluconazole, SCH 39304 | No | Died |

| Ng et al[16], 1994 | M/70 | Bangladesh | Diabetes mellitus, myelodysplasia | Facial pain, fever, epistaxis | Maxillary sinus | Amphotericin B, rifampin | No | Survived |

| Jayasuriya et al[17], 2006 | M/42 | Sri Lanka | None | Periorbital oedema, epiphora | Nasal sinuses | Amphotericin B | No | Survived |

| Righi et al[18], 2008 | M/41 | Italy | Acute myeloid leukaemia | Facial swelling, palatal oedema, purulent drainage in the oral cavity | Nasal sinuses, orbit, brain | Amphotericin B | Sinus surgery, Bone marrow transplantation | Died |

| LeBlanc et al[19], 2013 | M/15 | United States | Mixed lineage T-cell and myeloid acute leukemia, bone marrow transplantation | Facial pain, fever, epiphora | Nasal sinuses | Amphotericin B | No | Died |

| Present case, 2017 | F/50 | China | Acute myeloid leukaemia | Ocular proptosis, pain, visual loss, epiphora, nasal obstruction and rhinorrhea | Nasal sinuses, orbit, lung | Amphotericin B, meropenem, metronidazole, tigecycline, posaconazole | Sinus surgery, orbital decompression, orbital content enucleation | Died due to leukemia relapse |

The most common symptoms in our review were facial pain/swelling (five patients, 62.5%) and fever (four patients, 50%), followed by nasal obstruction/rhinorrhea/epistaxis (three patients, 37.5%), epiphora (three patients, 37.5%), and vision loss (two patients, 25%). Other symptoms included mental confusion (one patient, 12.5%), hearing loss (one patient, 12.5%), dyspnea (one patient, 12.5%), and purulent drainage in the oral cavity (one patient, 12.5%). In our review, the most commonly affected region was the paranasal sinuses (eight patients, 100%), followed by the orbit (three patients, 37.5%), brain (two patients, 25%), and lung (two patients, 25%). Payne et al[20] studied 41 cases of acute invasive fungal sinusitis and found that mucosal abnormalities of the middle turbinate and septum, specifically necrosis of the middle turbinate, could be important predictors of disease. Among eight patients, there were six with Cunninghamella infection confirmed by culture/biopsy from the nasal cavity, one with Cunninghamella infection confirmed by culture of the sputum, and one (our patient) with Cunninghamella infection confirmed by culture of the eye canthus secretions. It has been reported that middle turbinate biopsies have a sensitivity of 75% to 86% and a specificity of 100% for the diagnosis of acute invasive fungal sinusitis[21]. The middle turbinate has been found to be the most common site of invasion, followed by the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses. Our patient was found to have a necrotic and fragile middle turbinate during surgery, and postoperative pathology revealed mycotic infection.

In our review, four (50%) patients received drug and surgical treatments, while the other four (50%) received drug treatment only. Among the four patients receiving surgical treatment, all received nasal sinusectomy, two received orbit surgery, and one received jaw sinusotomy. In our review, all patients received antifungal drug treatment, such as amphotericin B (7/8, 87.5%), fluconazole (1/8, 12.5%), or posaconazole (1/8, 12.5%). Seven patients (all except Pt. 3) received amphotericin B treatment after culture/biopsy confirming Cunninghamella infection. Because the respiratory status of Patient 3 deteriorated quickly, he died before culture of his sputum confirmed Cunninghamella infection[15]. IFR is a lethal disease that has a very poor prognosis. In our opinion, confirmation by culture/biopsy and directed antifungal drug treatment are very important. Early empiric therapy must be started as soon as an invasive mold infection is suspected, and after confirmation and/or isolation of the fungus the treatment should be modified to ensure the appropriate drug and dosage[22]. Topical use of amphotericin B combined with endoscopic surgical debridement, followed by intravenous amphotericin B treatment, may constitute acceptable management for aggressive fungal infection[23]. Chen et al[24] studied 46 patients with invasive fungal sinusitis and suggested that early introduction of an anti-fungal agent and aggressive surgical debridement potentially decrease morbidity and mortality in high-risk patients. Other accompanying treatments should include tight regulation of blood glucose, management of diabetic ketoacidosis, and reversal of the underlying immunocompromised state when possible[25].

In our review, only three (3/8, 37.5%) patients survived; one had diabetes mellitus, one had diabetes mellitus and myelodysplasia, and one had no underlying disease. The others (5/8, 62.5%) died; four of them had acute leukemia, and the fifth had diabetes mellitus, sideroblastic anemia, and hemochromatosis. Turner et al[26] performed a systematic review of 52 studies and found that diabetic patients appear to have a better overall survival rate than patients with other comorbidities, while patients who have intracranial involvement, or who do not receive surgery as part of their therapy, have a poor prognosis. Schwartz et al[27] studied 54 consecutive patients with acute myelogenous leukemia and reported that major factors associated with cases ultimately developing IFD included the duration of chemotherapy, the number of sites colonized with fungi, and the number of fungal species isolated on certain surveillance cultures. According to the study of Dwyhalo et al[25], patients who are diagnosed and treated early, i.e., when the fungal load is low, have the best outcomes. In our case, the patient’s condition gradually stabilized after surgical debridement and antifungal drug treatment. However, she underwent chemotherapy again and her leukocyte count decreased, leading to fatal lung infection and hemoptysis.

IFR caused by Cunninghamella is very rare but has an extremely high fatality rate. The middle turbinate has been found to be the most common site of invasion, followed by the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses. Aggressive surgical debridements, followed by antifungal drug treatment both systematically and topically, are the most important fundamental treatments.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: El-Shazly AE, Vento S S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Santos T, Aguiar B, Santos L, Romaozinho C, Tome R, Macario F, Alves R, Campos M, Mota A. Invasive Fungal Infections After Kidney Transplantation: A Single-center Experience. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:971-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pagano L, Caira M, Candoni A, Offidani M, Fianchi L, Martino B, Pastore D, Picardi M, Bonini A, Chierichini A, Fanci R, Caramatti C, Invernizzi R, Mattei D, Mitra ME, Melillo L, Aversa F, Van Lint MT, Falcucci P, Valentini CG, Girmenia C, Nosari A. The epidemiology of fungal infections in patients with hematologic malignancies: the SEIFEM-2004 study. Haematologica. 2006;91:1068-1075. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Nicolato A, Nouér SA, Garnica M, Portugal R, Maiolino A, Nucci M. Invasive fungal diseases in patients with acute lymphoid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57:2084-2089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cohen-Abbo A, Bozeman PM, Patrick CC. Cunninghamella infections: review and report of two cases of Cunninghamella pneumonia in immunocompromised children. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:173-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Malkan AD, Wahid FN, Rao BN, Sandoval JA. Aggressive Cunninghamella pneumonia in an adolescent. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:581-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zarei M, Morris J, Aachi V, Gregory R, Meanock C, Brito-Babapulle F. Acute isolated cerebral mucormycosis in a patient with high grade non-Hodgkins lymphoma. Eur J Neurol. 2000;7:443-447. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ortín X, Escoda L, Llorente A, Rodriguez R, Martínez S, Boixadera J, Cabezudo E, Ugarriza A. Cunninghamella bertholletiae infection (mucormycosis) in a patient with acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:617-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Darrisaw L, Hanson G, Vesole DH, Kehl SC. Cunninghamella infection post bone marrow transplant: case report and review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25:1213-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cornely OA, Maertens J, Winston DJ, Perfect J, Ullmann AJ, Walsh TJ, Helfgott D, Holowiecki J, Stockelberg D, Goh YT, Petrini M, Hardalo C, Suresh R, Angulo-Gonzalez D. Posaconazole vs. fluconazole or itraconazole prophylaxis in patients with neutropenia. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:348-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1335] [Cited by in RCA: 1319] [Article Influence: 73.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hammond SP, Marty FM, Bryar JM, DeAngelo DJ, Baden LR. Invasive fungal disease in patients treated for newly diagnosed acute leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:695-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Su YY, Chang TY, Wang CJ, Jaing TH, Hsueh C, Chiu CH, Huang YC, Chen SH. Disseminated Cunninghamella bertholletiae Infection During Induction Chemotherapy in a Girl with High-Risk Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Pediatr Neonatol. 2016;57:531-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Strasfeld L, Espinosa-Aguilar L, Gajewski JL, Stenzel P, Pimentel A, Mater E, Maziarz RT. Emergence of Cunninghamella as a pathogenic invasive mold infection in allogeneic transplant recipients. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13:622-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Brennan RO, Crain BJ, Proctor AM, Durack DT. Cunninghamella: a newly recognized cause of rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1983;80:98-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chetchotisakd P, Boonma P, Sookpranee M, Pairojkul C. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: a report of eleven cases. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1991;22:268-273. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kontoyianis DP, Vartivarian S, Anaissie EJ, Samonis G, Bodey GP, Rinaldi M. Infections due to Cunninghamella bertholletiae in patients with cancer: report of three cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:925-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ng TT, Campbell CK, Rothera M, Houghton JB, Hughes D, Denning DW. Successful treatment of sinusitis caused by Cunninghamella bertholletiae. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:313-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jayasuriya NS, Tilakaratne WM, Amaratunga EA, Ekanayake MK. An unusual presentation of rhinofacial zygomycosis due to Cunninghamella sp. in an immunocompetent patient: a case report and literature review. Oral Dis. 2006;12:67-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Righi E, Giacomazzi CG, Lindstrom V, Albarello A, Soro O, Miglino M, Perotti M, Varnier OE, Gobbi M, Viscoli C, Bassetti M. A case of Cunninghamella bertholettiae rhino-cerebral infection in a leukaemic patient and review of recent published studies. Mycopathologia. 2008;165:407-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | LeBlanc RE, Meriden Z, Sutton DA, Thompson EH, Neofytos D, Zhang SX. Cunninghamella echinulata causing fatally invasive fungal sinusitis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;76:506-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Payne SJ, Mitzner R, Kunchala S, Roland L, McGinn JD. Acute Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis: A 15-Year Experience with 41 Patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;154:759-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Middlebrooks EH, Frost CJ, De Jesus RO, Massini TC, Schmalfuss IM, Mancuso AA. Acute Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis: A Comprehensive Update of CT Findings and Design of an Effective Diagnostic Imaging Model. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:1529-1535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Krcmery V, Kunova E, Jesenska Z, Trupl J, Spanik S, Mardiak J, Studena M, Kukuckova E. Invasive mold infections in cancer patients: 5 years' experience with Aspergillus, Mucor, Fusarium and Acremonium infections. Support Care Cancer. 1996;4:39-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Saedi B, Sadeghi M, Seilani P. Endoscopic management of rhinocerebral mucormycosis with topical and intravenous amphotericin B. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125:807-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chen CY, Sheng WH, Cheng A, Chen YC, Tsay W, Tang JL, Huang SY, Chang SC, Tien HF. Invasive fungal sinusitis in patients with hematological malignancy: 15 years experience in a single university hospital in Taiwan. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dwyhalo KM, Donald C, Mendez A, Hoxworth J. Managing acute invasive fungal sinusitis. JAAPA. 2016;29:48-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Turner JH, Soudry E, Nayak JV, Hwang PH. Survival outcomes in acute invasive fungal sinusitis: a systematic review and quantitative synthesis of published evidence. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1112-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Schwartz RS, Mackintosh FR, Schrier SL, Greenberg PL. Multivariate analysis of factors associated with invasive fungal disease during remission induction therapy for acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer. 1984;53:411-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |