Published online Jan 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i2.215

Peer-review started: September 23, 2018

First decision: November 14, 2018

Revised: December 4, 2018

Accepted: December 14, 2018

Article in press: December 15, 2018

Published online: January 26, 2019

Processing time: 126 Days and 22.5 Hours

Infiltrative adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) of the extrahepatic bile duct is reported infrequently, which is an unusual variant of the ordinary adenocarcinoma. The simultaneous development of ASC and cystadenocarcinoma in the extrahepatic biliary tree is rare. In addition, the accurate preoperative diagnosis of concomitant carcinoma in the multiple biliary trees at an early stage is often difficult. Thus, awareness of the risk of the multiplicity of biliary tumors is perhaps the most important factor in identifying these cases.

Here, we report a case of a 63-year-old female with jaundice, who was referred to Shuguang Hospital because of abdominal pain for 1 mo. An abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a type I choledochal cyst and intraluminal masses suggestive of adenoma of the common bile duct. In addition, a preoperative diagnosis of a concomitant Klatskin tumor and type I choledochal cyst was made. The patient underwent anti-inflammatory therapy, followed by radical surgery due to hilar cholangiocarcinoma and resection of the choledochal cyst. Examination of the surgical specimen revealed a papillary tumor of the common bile duct, which arose from the malignant transformation of a pre-existing cystadenoma. Histologic examination confirmed a special type of cholangiocarcinoma; the tumor in the hilar bile duct was an ASC, whereas the tumor in the common bile duct was a moderately differentiated cystadenocarcinoma. The patient showed rapid deterioration 8 mo after surgery.

Although concomitant ASC and cystadenocarcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct is difficult to diagnose before surgery, and the prognosis is poor after surgery, surgical resection is still the preferred treatment.

Core tip: We describe a patient with adenosquamous carcinoma of the hilar bile duct associated with cystadenocarcinoma of the common bile duct, who was treated with surgery. Although concomitant adenosquamous carcinoma and cystadenocarcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct is difficult to diagnose before surgery, and the prognosis is poor after surgery, surgical resection is still the preferred treatment.

- Citation: Lu BJ, Cao XD, Yuan N, Liu NN, Azami NL, Sun MY. Concomitant adenosquamous carcinoma and cystadenocarcinoma of the extrahepatic bile duct: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(2): 215-220

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i2/215.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i2.215

Adenosquamous carcinoma (ASC) is a rare histological type of biliary tract cancer, which has been described as an infiltrative bile duct (BD) cancer containing two malignant components: adenocarcinoma (AC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Cystadenocarcinoma is characterized by a mixture of tumor cysts and solid neoplastic regions. The incidence of BD origin is only 5-10%[1], and around 90% occur in the intrahepatic ducts.

Currently, literature describing multiple synchronous tumors of the extrahepatic biliary tree is very limited. Herein, we present both the clinical and pathological features, as well as the clinical course of a patient with concomitant ASC of the hilar BD (HBD) and cystadenocarcinoma of the common BD (CBD).

A 63-year-old Chinese woman was admitted to Shuguang Hospital due to abdominal pain for 1 mo.

Abdominal pain accompanied by back pain occurred without obvious cause and worsened over time. After anti-inflammatory treatment, the patient experienced temporary pain relief.

She recalled a history of gallstones.

No additional family history nor bad personal habits were presented.

Pulse and blood pressure were within the normal range. With the exception of icterus, physical examination did not identify any abnormalities such as abdominal tenderness, rebound tenderness, guarding of the abdomen, palpable mass, or hepatomegaly.

Laboratory data showed elevated total bilirubin (2.2 mg/dL, normal range 0.2-1.2), alanine transaminase (60 U/L, normal range 0-35), aspartate transaminase (40 U/L, normal range 0-35), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (244.95 U/L, normal range 8-60). Tumor markers were within normal limits, except for a slight elevation in alpha-fetoprotein (7.1 ng/mL, normal range 0-16.7) and carbohydrate antigen 12-5 (54.6 U/mL, normal range 0-41).

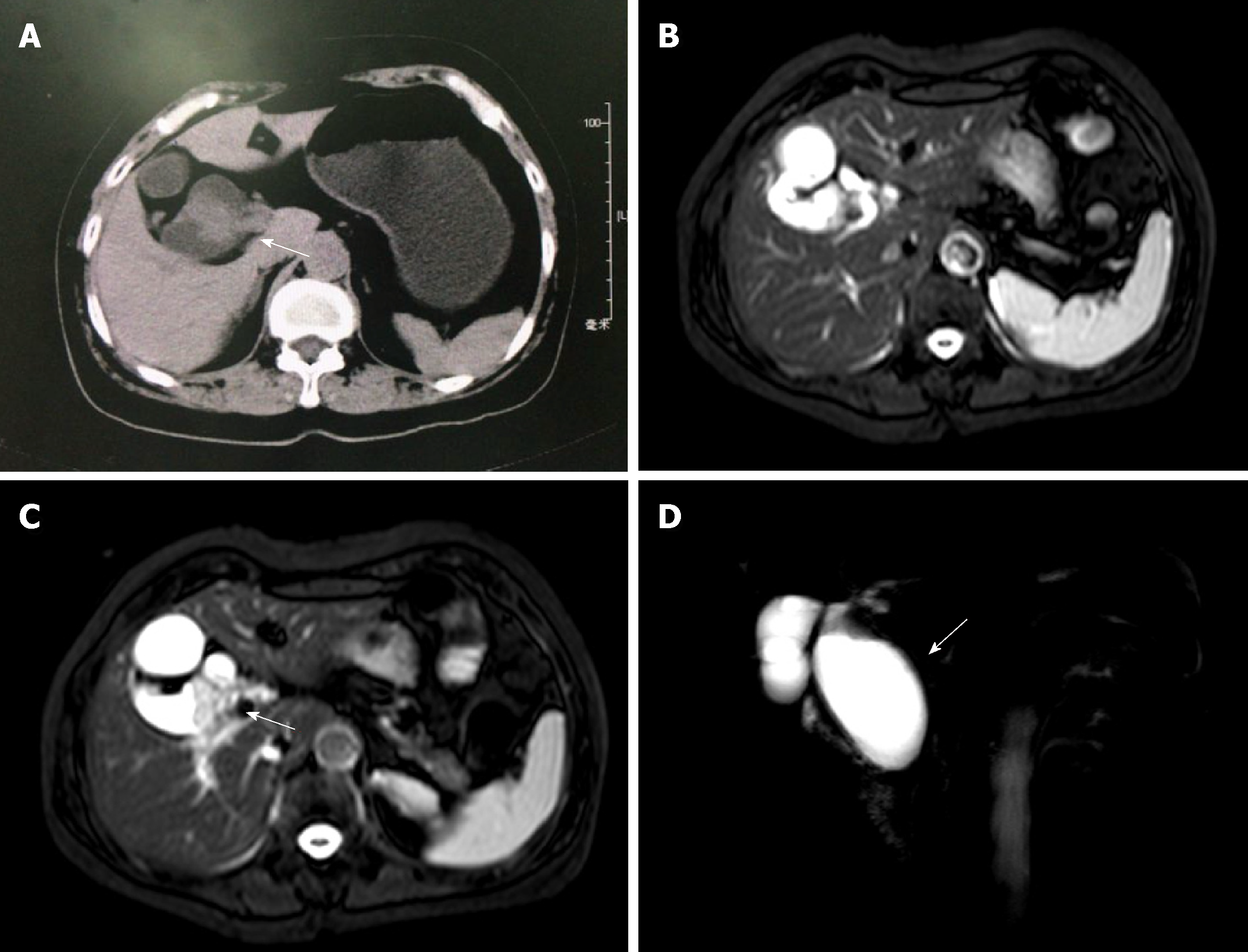

Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a type I choledochal cyst and intraluminal masses suggestive of adenoma of the CBD; however, the malignant potential of the lesions could not be excluded (Figure 1A). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed CBD dilatation, a cystic mass in the lumen of the CBD and an irregular space-occupying lesion in the HBD.

A diagnosis of a Klatskin tumor and a type I choledochal cyst was made (Figure 1B-D).

The patient underwent radical surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma and resection of a choledochal cyst. During surgery, the extrahepatic BD (EHBD) was found to be clearly thickened by approximately 5 cm, and there was a 3 cm mass-like structure in the lower common hepatic duct, which penetrated the wall without invading the serosa. Enlarged hilar lymph nodes or gallbladder stones were not observed. No metastases were found in the liver, spleen, or other abdominal organs. There was also no evidence of local metastatic involvement of the regional lymph nodes. Thus, no hepatectomy, pancreatectomy or lymphadenectomy was performed. Intraoperative frozen sections were done to examine proximal and distal margin status, and all the resection margins were free of residual cancer cells. The operation lasted for more than 4 h, and the intraoperative blood loss was about 300 mL. No blood transfusion was performed.

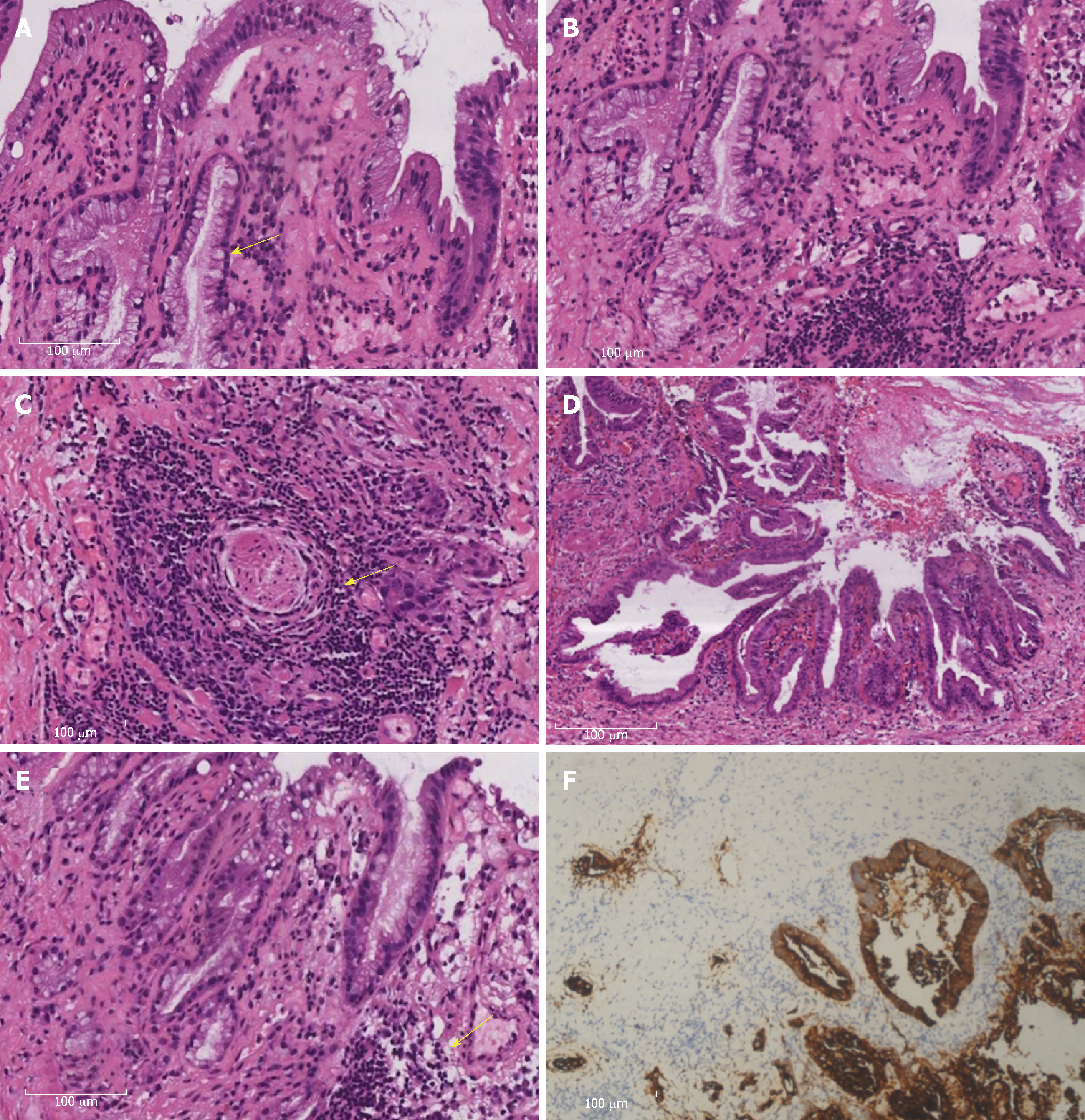

The patient received a combination of postoperative analgesia and prophylactic antibiotics. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed according to routine laboratory protocols. In addition, immunohistochemical staining was performed to define the origin of the cystic structures. Histologic examination showed a special type of cholangiocarcinoma (CC), namely ASC of the HBD associated with cystadenocarcinoma of the CBD. On the one hand, the Klatskin tumor showed a mixture of AC and SCC, where the AC portion included easily recognizable gland-like structures and focally abundant mucus production (Figure 2A-B). On the other hand, SCC was mixed with the AC region and occurred as separate sheets of malignant cells. Well-differentiated SCC was characterized by cell atypia and pleomorphism, as well as focal keratinization, with keratin pearls and individual cell keratinization (Figure 2C). Moreover, a malignant tumor with a papillary and glandular pattern was found in the CBD; the lining cells were cuboidal with mild to moderate nuclear atypia (Figure 2D-E). Immunohistochemistry showed positive cytokeratin (CK) 7 (Figure 2F). A definitive diagnosis of concomitant ASC of the HBD and cystadenocarcinoma of the CBD was given.

The patient recovered and was discharged on postoperative day 14 in good condition, and was followed closely as an outpatient under hepatobiliary surgery services. In terms of diet, the patient was advised to strengthen her nutrition. Unfortunately, at the end of the 8 mo follow-up, there were multiple metastases.

Since the 1980s, the age-adjusted incidence rates of extrahepatic CC have remained stable[2]. ASC of the EHBD has been reported to account for approximately 2% of extrahepatic CC. The overall 1-year, 2-year and 5-year survival rates for patients with ASC of the BD are 30.1%, 11.3%, and 3.7%, respectively, and the median survival is 14.0, 6.0 and 6.0 mo for ampulla of Vater, EHBD and intrahepatic bile duct ASC, respectively[3]. Patients with choledochal cysts, particularly type I and IV, have an up to 50-fold increased risk of developing CC, with a lifetime incidence rate of 6% to 30%[4]. It has been hypothesized that cystadenocarcinoma results from the malignant degeneration of pre-existing cystadenoma, which has a risk of malignant transformation as high as 20-30%[5].

The diagnosis of CC is challenging, as the clinical presentation is often insidious and frequently nonspecific. Globally, the average age at diagnosis is over 50 years. Several serum tumor markers (CA 19-9, CEA, and CA-125) may be elevated in patients with CC. However, not one of these serum markers is specific. MRCP is noninvasive and provides additional information on the extent of extra-biliary tumor, vascular encasement, the relation of the primary tumor to surrounding structures, and intra- as well as extrahepatic metastases[6]. In addition, fluorescence in situ hybridization has been demonstrated to increase the sensitivity of cytology for diagnosing CC[7]. Cystadenocarcinoma can be morphologically differentiated from CC by its cystic features, and CT and MRI are helpful in making a diagnosis. In malignant lesions, most tumor cells are positive in immunohistochemical staining with antibodies to CK; however, immunohistochemistry does not yield a diagnostic immune profile to distinguish cystadenoma from cystadenocarcinoma.

The histologic types of CC include intestinal type AC, clear cell AC, signet-ring cell carcinoma, ASC, SCC, and small cell carcinoma[8]. The World Health Organization tumor classification system (2010) makes a clear distinction between ASC, which contains malignant glandular and squamous elements, and AC, including benign squamous metaplasia, which is mainly caused by chronic inflammation, gallstones or choledochal cysts undergoing malignant transformation. Additionally, the SCC component of ASC is closely related to an advanced AC and displays a higher proliferative capacity[9], whereas pure SCC is rare and may be associated with chronic cholangitis. ASC is clinically more aggressive and has a less favorable prognosis than AC, but a better prognosis than SCC, which grows twice as fast as AC. Once AC transforms to ASC, the carcinoma is highly malignant[10]. Kim et al[11] reported a higher incidence of lymph node metastasis in patients with ASC than in those with AC, with a node-positive rate of more than 80%. Most biliary cystic neoplasms, including cystadenomas and malignant cystadenocarcinomas, arise from the hepatobiliary epithelium. Since Hueter first reported cystadenocarcinoma in 1887, its pathophysiology has not been completely determined[12]. The possible pathogenesis correlates with ductal plate malformations (DPM)[13], as first proposed by Jorgenson MJ. The embryological ductal plate is a double-layered tubular column of precursor hepatoblasts, which surround the portal vein radicle and progressively differentiate into future BDs[14]. However, Terada et al[15] suggested that this DPM-like structure in cystadenocarcinoma was not true DPM, but rather represented structural atypia related to carcinoma cells. Besides, some authors favor an acquired etiology, such as a reactive process to a focal injury. Occasionally, genetic alterations with Kras mutations may occur in regions of low- and high-grade dysplasia.

Currently, complete surgical resection represents the only potentially curative treatment option for biliary tract cancer, and surgical outcomes have improved significantly in the 2000s due to careful patient selection, lower surgical mortality rates and higher R0 resection rates. Moreover, the benefits of chemotherapy and radiotherapy as adjuvant therapies for resected biliary tract cancer are under investigation. The only chemotherapeutic drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration for CC is gemcitabine, which, along with oxaliplatin, has been used as the standard treatment for unresectable CC in non-cirrhotic patients[16]. Even so, most patients may have a dismal prognosis and encounter early recurrence and distant metastasis after surgery.

In summary, although multiple carcinomas occurring in different parts of the gastrointestinal tract are known, concomitant ASC and cystadenocarcinoma of the EHBD is regarded as relatively rare. MRCP, combined with laboratory testing and clinical data, is a valuable method for early diagnosis of hepatobiliary origin tumors. Of course, accurate diagnosis still depends on pathological features. Once the patient is diagnosed, surgery should be performed as soon as possible to reduce recurrence and prolong survival.

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Li-Li Wu (Department of Pathology at Shuguang Hospital, Shanghai) for her comments on this case.

CARE Checklist (2013) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2013), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2013).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Gupta R, Neri V, Yoshida H S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Jwa EK, Hwang S. Clinicopathological features and post-resection outcomes of biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma of the liver. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2017;21:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Khan SA, Emadossadaty S, Ladep NG, Thomas HC, Elliott P, Taylor-Robinson SD, Toledano MB. Rising trends in cholangiocarcinoma: is the ICD classification system misleading us? J Hepatol. 2012;56:848-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Qin BD, Jiao XD, Yuan LY, Liu K, Zang YS. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the bile duct: a population-based study. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:439-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Blechacz B, Komuta M, Roskams T, Gores GJ. Clinical diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:512-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 427] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 38.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kubota E, Katsumi K, Iida M, Kishimoto A, Ban Y, Nakata K, Takahashi N, Kobayashi K, Andoh K, Takamatsu S, Joh T. Biliary cystadenocarcinoma followed up as benign cystadenoma for 10 years. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:278-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rizvi S, Gores GJ. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1215-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 923] [Cited by in RCA: 966] [Article Influence: 80.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Moreno Luna LE, Kipp B, Halling KC, Sebo TJ, Kremers WK, Roberts LR, Barr Fritcher EG, Levy MJ, Gores GJ. Advanced cytologic techniques for the detection of malignant pancreatobiliary strictures. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1064-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Blechacz BR, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2008;12:131-150, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hoshimoto S, Hoshi S, Hishinuma S, Tomikawa M, Shirakawa H, Ozawa I, Wakamatsu S, Hoshi N, Hirabayashi K, Ogata Y. Adenosquamous carcinoma in the biliary tract: association of the proliferative ability of the squamous component with its proportion and tumor progression. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:425-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Okabayashi T, Kobayashi M, Nishimori I, Namikawa T, Okamoto K, Onishi S, Araki K. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the extrahepatic biliary tract: clinicopathological analysis of Japanese cases of this uncommon disease. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:192-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim WS, Jang KT, Choi DW, Choi SH, Heo JS, You DD, Lee HG. Clinicopathologic analysis of adenosquamous/squamous cell carcinoma of the gallbladder. J Surg Oncol. 2011;103:239-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Soares KC, Arnaoutakis DJ, Kamel I, Anders R, Adams RB, Bauer TW, Pawlik TM. Cystic neoplasms of the liver: biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:119-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Arora A, Bansal K, Sureka B, Rajesh S. Choledochal cysts: sequel of the malformed embryological ductal plate? Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:2062-2064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Terada T. Human ductal plate and its derivatives express antigens of cholangiocellular, hepatocellular, hepatic stellate/progenitor cell, stem cell, and neuroendocrine lineages, and proliferative antigens. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2017;242:907-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Terada T. Hepatobiliary cystadenocarcinoma of the liver with features of ductal plate malformations. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:197-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira SP, Roughton M, Bridgewater J; ABC-02 Trial Investigators. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2617] [Cited by in RCA: 3165] [Article Influence: 211.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |