Published online Jan 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i2.209

Peer-review started: September 2, 2018

First decision: October 4, 2018

Revised: December 23, 2018

Accepted: December 29, 2018

Article in press: December 30, 2018

Published online: January 26, 2019

Processing time: 148 Days and 6.1 Hours

Colonic lipomas are rare, slow-growing benign tumors. Colonic lipomas are generally asymptomatic and are found incidentally. Although cases of cecal lipoma have been sporadically reported in the literature, the disease has not been systematically reviewed.

We present a 44-year-old man who underwent a routine physical check-up during which colonoscopic examination revealed an asymptomatic 1.5-cm cecal mass at the appendiceal orifice. Laparoscopic exploration was performed that also demonstrated a congested and erythematous appendix. En bloc resection of both the cecum and vermiform appendix was performed because of the suspicion of malignancy. Histopathological examination revealed a cecal lipoma composed of mature adipose tissue, and the appendix showed subclinical inflammation. Our procedures and findings were discussed, along with relevant English literature that was retrieved from the PubMed database from 2000 to 2017. Twenty-six cases, including ours, were reported. Consistent with the findings of the literature, it is difficult to obtain a definitive diagnosis by colonoscopic biopsy.

Surgery remains the treatment of choice for this condition. Intraoperative frozen pathological sectioning helped the surgeon decide the extent of surgery, and radical surgery was avoided. Excision of benign lesions occupying the appendiceal orifice may be indicated for the prevention of later development of acute appendicitis. The prognosis is generally good, with only one of the 26 reported patients complicated with acute appendicitis, who subsequently succumbed due to severe comorbidities and sepsis.

Core tip: All patients with cecal lipoma reported in the literature were treated with radical right hemicolectomy because malignancy could not be completely ruled out before surgery. However, in our presented case, intraoperative frozen histopathological sectioning helped the surgeon decide the extent of surgery, and radical surgery was avoided. Furthermore, excision of benign lesions occupying the appendiceal orifice may be indicated for the prevention of later development of acute appendicitis.

- Citation: Tsai KJ, Tai YS, Hung CM, Su YC. Cecal lipoma with subclinical appendicitis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(2): 209-214

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i2/209.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i2.209

Colonic lipomas are rare, slow-growing benign tumors. However, they constitute most nonepithelial neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract[1]. Colonic lipomas are generally asymptomatic and are found incidentally during colonoscopy, surgery for other conditions or autopsy[2]. Although cases of cecal lipoma have been sporadically reported in the literature, the condition has not been systematically reviewed. We hereby present an asymptomatic patient with a cecal lipoma located at the orifice of the vermiform appendix with subclinical appendicitis. Histopathological study confirmed the diagnosis of a cecal lipoma obstructing the appendiceal orifice causing a chronic inflammatory change of the appendix. Relevant English literature was retrieved from the PubMed database from 2000 to 2017 using the keywords “cecal lipoma”, “ileocecal valve lipoma” and “appendix”. In total, twenty-six cases, including ours, were reviewed regarding the clinical manifestations, treatment and prognosis.

A 44-year-old man without known systemic diseases had a 1.5-cm sessile polypoid mass with intact overlying mucosa found during a colonoscopy as part of a regular health examination.

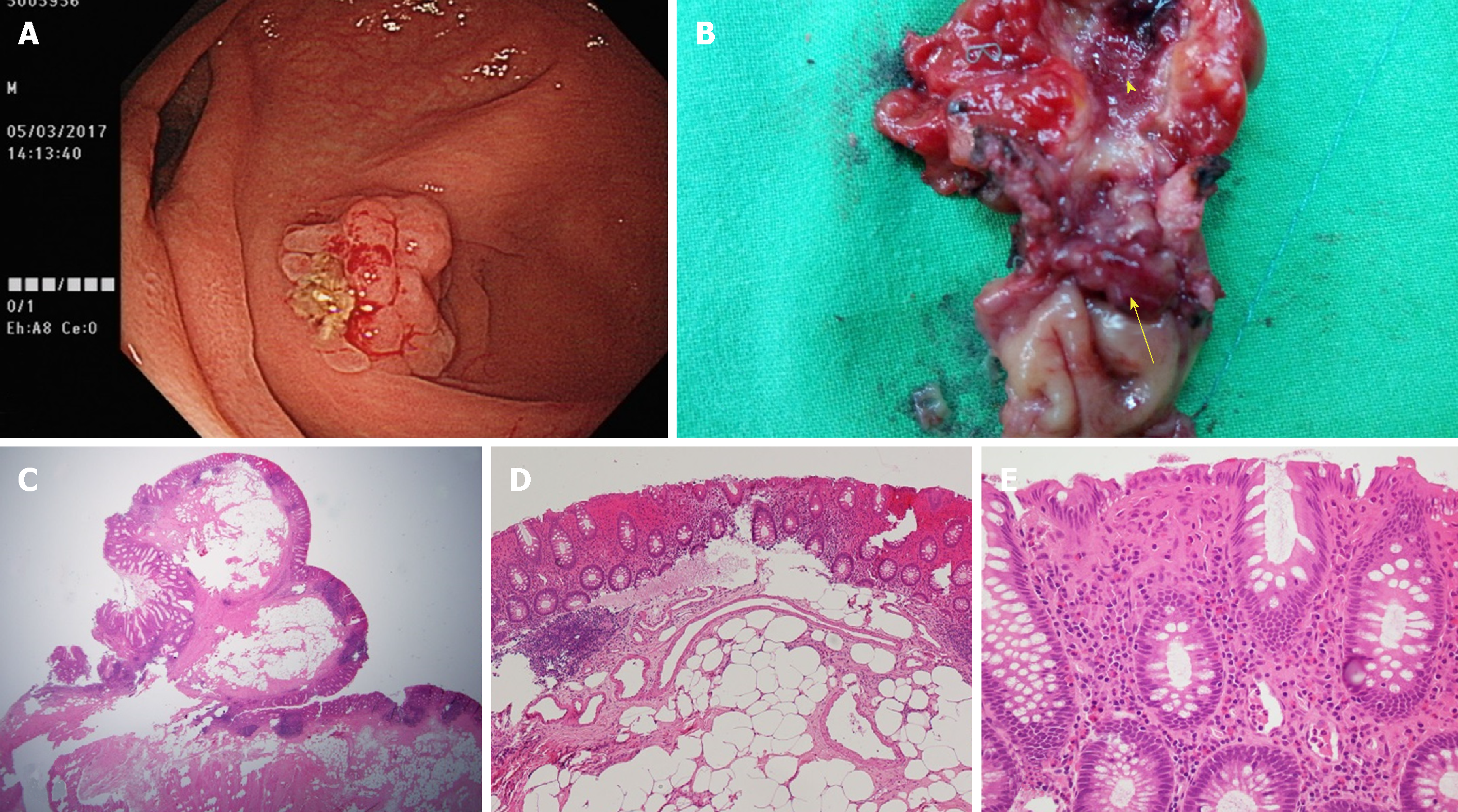

The cecal mass occupied the appendiceal lumen and was prone to bleeding on contact (Figure 1A).

The patient had never experienced any abdominal pain, bowel movement irregularity or body weight loss prior to this medical check-up. He did not have a history of alcohol abuse or consumption of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

He was not anemic or icteric at the time of physical examination, which showed no tenderness or mass over the abdomen.

Laboratory studies, including carcinoembryonic antigen, were all within normal limits. The idea of endoscopic resection of the lesion was declined due to its submucosal location, which may have predisposed to bleeding and cecal perforation during the procedure. As a result, laparoscopic segmental resection was scheduled because malignancy could not be ruled out.

Cecal lipoma with subclinical appendicitis.

During laparoscopic exploration of the peritoneal cavity, a swollen and erythematous vermiform appendix with adhesions to the adjacent mesentery and omentum was noted. The appendix and partial cecum were resected en bloc with an articulating endoscopic linear cutter (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., OH, USA). Gross examination of the resected specimen showed a polypoid mass obstructing the appendiceal lumen lined with inflammatory and erythematous mucosa. A frozen section of the specimen demonstrated a benign inflammatory polyp for which the operation was terminated without proceeding to radical right hemicolectomy. Histopathological examination of the specimen demonstrated mature adipose cells inside the polypoid mass (Figure 1B) with mixed neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrations in the overlying mucosa (Figure 1C). In addition, lymphocytic infiltration was noted in the appendiceal mucosa, with lymphoid hyperplasia in the submucosa (Figure 1D). The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and he was discharged on the third day after the surgery.

Twenty-five case reports of cecal lipoma, including ileocecal valve lipoma, were collected from the PubMed English database during the period from 2000 to 2017. After adding our case into the database, there were a total of twenty-six cases that showed a slight female predominance (n = 17, 65.4%). The average age of the patients was 55.2 ± 13.6 years (32-77). The predominant clinical symptoms were abdominal pain (80.8%), hematochezia (23.1%), bowel habit change (19.2%), and body weight loss (15.4%) (Table 1). There were two cases (7.7%) of asymptomatic cecal lipoma found in routine health check-ups. The most common preoperative diagnosis was acute or chronic recurrent intussusception (46.2%), followed by cecal mass with or without bleeding (38.5%). The remaining four patients were preoperatively diagnosed as having acute appendicitis, mucocele of the appendix, cecal volvulus, and intestinal obstruction, respectively (Table 2). The average size of cecal lipoma in the 23 reported cases was 5.4 ± 2.3 cm (range, 1.5-10 cm). There were 12 cases with documentation of the gross morphology of the lesions, of which 8 were pedunculated and 4 were sessile. Regarding the location of the lipoma, 13 cases were in the cecal wall, 8 were in the ileocecal valve, and 3 in were the appendiceal orifice, with two cases unreported. Of the three cases with appendiceal involvement, pathological examinations demonstrated the location of cecal lipoma over the appendiceal orifice in two cases with acute suppurative appendicitis[3,4]. Our case was the only one that showed features of chronic appendicitis.

| Symptoms | No. of patients | Prevalence |

| Abdominal pain | 21 | 80.8% |

| Hematochezia | 6 | 23.1% |

| Bowel habit change | 5 | 19.2% |

| Body weight loss | 4 | 15.4% |

| No symptoms | 2 | 7.7% |

| Pre-operative diagnosis | No. of patients | Prevalence |

| Intussusception | 12 | 46.2% |

| Cecal mass | 10 | 38.5% |

| Acute appendicitis | 1 | 3.8% |

| Mucocele of the appendix | 1 | 3.8% |

| Cecal volvulus | 1 | 3.8% |

| Intestinal obstruction | 1 | 3.8% |

Chronic appendicitis is an uncommon clinical entity usually presenting as a less severe, nearly continuous abdominal pain often lasting for weeks, months or even years[5]. Chronic appendicitis was thought to be due to partial, but persistent, obstruction of the appendiceal lumen[6]. The causes of intermittent or partial appendiceal obstruction include fecalith, tumors, lymphoid hyperplasia, foreign bodies, and appendiceal folding[7]. Chronic appendicitis may also occur without any clinical manifestations, as in our presented case. However, overt clinical symptoms may later become apparent if the mass is left untreated. The cecal lipoma in our case was found incidentally in a regular physical check-up without preceding symptoms. The gastroenterologist declined the decision of preoperative tissue biopsy because of a high false-negative rate for diagnosis of malignancy, probability of biopsy site bleeding, the sessile stalk of the polyp and little help in surgical decision making[8]. We proceeded with the surgery because of the possibility of malignancy and potential symptomatic appendicitis in the future.

Colonic lipomas are often silent. Those larger than 2 cm may occasionally cause abdominal pain, changes of bowel habits, rectal bleeding and bowel obstruction, intussusception or prolapse[9].

Taking into account the unique anatomic features of the cecum in comparison with other parts of the colon, such as the relative mobility of the cecum, the existence of the appendix and the ileocecal valve, cecal lipoma of a relatively small size could have a higher possibility of inducing pathological changes or even clinical symptoms than other colon locations.

Pedunculated lipomas less than 2 cm can be removed via colonoscopy. For a sessile type of lipoma, or a tumor size larger than 2 cm, colonoscopic resection should not be performed because of the potential risk of perforation. Colonoscopic biopsy is not recommended in patients with suspected colonic lipoma because biopsies of these submucosal lesions are often thought to be inadequate for histological diagnosis[10].

Tholoor et al[11] reported the polyps involving the appendiceal orifice as among the “difficult polyps” for endoscopic resection, which has been shown to be associated with a high risk of recurrence or perforation in this location. Hence, open surgery is generally the preferred approach.

In our literature review, pathological diagnosis of lipoma was not established in all cases before surgical excision. In view of possible malignancy and potential tumor complications, such as intestinal obstruction, bleeding and intussusception, we recommend surgical intervention in all cases if colonoscopic resection is not feasible. This strategy is primarily to establish the diagnosis so that aggressive therapeutic approaches for more common malignant colonic lesions (e.g., primary colonic carcinoma) can be avoided, and secondarily to obviate possible appendicitis, tumor bleeding and colonic intussusception or obstruction. The choice of excision method (e.g., lipomectomy via colotomy or segmental resection of bowel) should be based on individual cases. In cases where malignancy cannot be ruled out preoperatively, formal radical hemicolectomy should be performed through either a laparoscopic approach or conventional laparotomy[12]. In our case, a frozen section of the specimen was of great assistance to determine the range of resection and to avoid radical right hemicolectomy.

Review of the literature demonstrated that only one patient expired after surgery due to acute appendicitis complicated with septic shock and severe comorbidities[3], while all others recovered well postoperatively, suggesting the safety of surgical treatment for this patient population.

We presented a case of incidentally diagnosed cecal lipoma that was successfully treated with limited laparoscopic resection based on the result of intraoperative pathological frozen section. Our case highlighted the importance of intraoperative pathological diagnosis in guiding the extent of resection when preoperative diagnosis of a cecal lesion remains uncertain.

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Department of Research, E-Da Hospital, I-Shou University for English editing.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Burke BA, Dinc B, Mohamed AA, Wani IA S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Ghidirim G, Mishin I, Gutsu E, Gagauz I, Danch A, Russu S. Giant submucosal lipoma of the cecum: report of a case and review of literature. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14:393-396. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Nallamothu G, Adler DG. Large colonic lipomas. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7:490-492. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Hagan I, Corr C, Shepherd N, McGann G. Acute suppurative appendicitis complicating ileocolic intussusception due to a caecal lipoma. Eur J Radiol. 2006;60:113-115. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mohamed A, Hassan N, Bhat N, Abukhater M, Uddin M. Caecal lipoma, unusual cause of recurrent appendicitis, case report and literature review. Internet J Gastroenterol. 2008;8. |

| 5. | See TC, Watson CJ, Arends MJ, Ng CS. Atypical appendicitis: the impact of CT and its management. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2008;52:140-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shah SS, Gaffney RR, Dykes TM, Goldstein JP. Chronic appendicitis: an often forgotten cause of recurrent abdominal pain. Am J Med. 2013;126:e7-e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kothadia JP, Katz S, Ginzburg L. Chronic appendicitis: uncommon cause of chronic abdominal pain. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2015;8:160-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chen CH, Wu KL, Hu ML, Chiu YC, Tai WC, Chiou SS, Chuah SK. Is a biopsy necessary for colon polyps suitable for polypectomy when performing a colonoscopy? Chang Gung Med J. 2011;34:506-511. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Vecchio R, Ferrara M, Mosca F, Ignoto A, Latteri F. Lipomas of the large bowel. Eur J Surg. 1996;162:915-919. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Chung YF, Ho YH, Nyam DC, Leong AF, Seow-Choen F. Management of colonic lipomas. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68:133-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tholoor S, Tsagkournis O, Basford P, Bhandari P. Managing difficult polyps: techniques and pitfalls. Ann Gastroenterol. 2013;26:114-121. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Mantzoros I, Raptis D, Pramateftakis MG, Kanellos D, Psomas S, Makrantonakis A, Tsachalis T, Angelopoulos S. Colonic lipomas: our experience in diagnosis and treatment. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15 Suppl 1:S71-S73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |