Published online Oct 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i19.3160

Peer-review started: June 26, 2019

First decision: July 31, 2019

Revised: August 9, 2019

Accepted: August 27, 2019

Article in press: August 27, 2019

Published online: October 6, 2019

Processing time: 102 Days and 2.8 Hours

Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus accounts for 0.1%-0.2% of all esophageal malignancies, including melanotic and amelanotic melanomas. Primary amelanotic malignant melanoma of the esophagus is extremely rare, and only about 20 cases have been published in the literature to date. Most primary malignant melanomas of the esophagus are diagnosed following development of metastatic lesions and thus have a very poor prognosis. The median survival duration of patients with metastatic melanoma has been reported to be 6.2 mo.

A 49-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with a diagnosis of esophageal cancer. Endoscopy, biopsy, imaging evaluation, and physical examination at our hospital indicated a diagnosis of advanced primary amelanotic malignant melanoma of the esophagus. Immunohistochemical staining confirmed melanoma. Nuclear medicine examination revealed a left iliac bone metastatic lesion. After discharge, the patient self-administered apatinib for 3 mo, followed by oral treatment with Chinese medicines (also self-administered) for 2 mo. No treatments had been taken since then. The patient has survived with no growth out to the most recent follow-up (24 mo post diagnosis), and she always presented with a positive attitude about her condition during this period.

Survival following metastatic melanoma might be related to the pharmaceutical and Chinese medicine treatment and the patient's positive attitude.

Core tip: Primary amelanotic malignant melanoma of the esophagus is an extremely rare disease . We report here a 49-year-old woman with advanced primary amelanotic malignant melanoma of the esophagus diagnosed by endoscopy, biopsy, imaging evaluation, and physical examination, and confirmed by immunohistochemical staining. This patient's survival was much longer than other that of metastatic melanoma patients, without effective treatment. We hypothesize that this outcome might be related to the Western drug and Chinese medicine treatments as well as the patient's positive attitude and emotional state. It may be of great benefit towards extending the survival period of patients with metastatic melanoma through psychological intervention.

- Citation: Zhang RX, Li YY, Liu CJ, Wang WN, Cao Y, Bai YH, Zhang TJ. Advanced primary amelanotic malignant melanoma of the esophagus: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(19): 3160-3167

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i19/3160.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i19.3160

Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus (PMME) originates from the basal melanocytes of the esophageal squamous epithelium and is a rare malignant tumor, accounting for 0.1%-0.2% of all esophageal malignancies and 0.5% of all noncutaneous melanomas with an estimated incidence of 0.0036 cases per million/year[1]. Only 339 cases had been reported worldwide by 2016, most as individual case reports[2]. About 2% of all esophageal melanomas are amelanotic[3], and only about 20 cases have been published in the literature so far. By the time of PMME diagnosis, 30%-40% of patients have already developed metastatic lesions, and 40%-80% of those patients have periesophageal, mediastinal, and celiac lymph node metastases[4]. Therefore, the disease has a very poor prognosis.

Amelanotic malignant melanomas (AMMs) tend to be diagnosed at even more advanced periods, due to higher invasiveness and misdiagnosis as other nonpigmented tumors. The overall survival of AMMs is lower than that of pigmented malignant melanomas (PMMs)[5]. We report herein a patient with advanced primary amelanotic malignant melanoma of the esophagus who received 5 mo of sequential Western drug (3 mo) and Chinese medicine (2 mo) treatment and was alive at 19 mo after treatment completion.

A 49-year-old woman had undergone endoscopic biopsy in a local hospital and was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. She presented to our hospital with the complaint of dysphagia that manifested with intake of solid foods. She reported that the dysphagia had begun 6 mo prior and worsened 3 mo ago.

The patient had a history of progressive dysphagia and retrosternal pain for more than 6mo.

No specific related past illness was found.

The patient had no specific personal or family history of any cancer or related disease.

No signs of cutaneous or extracutaneous malignant melanoma were found.

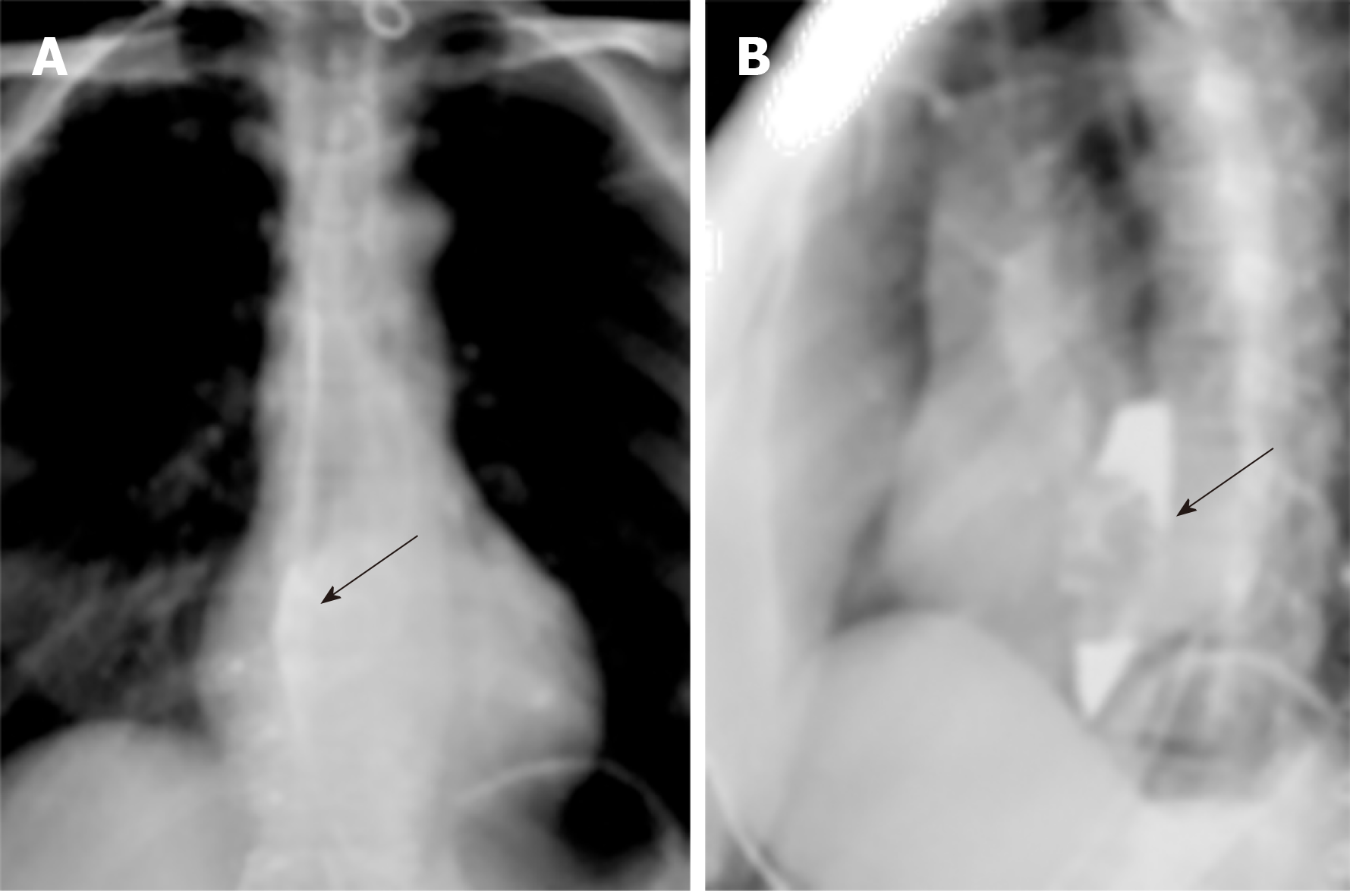

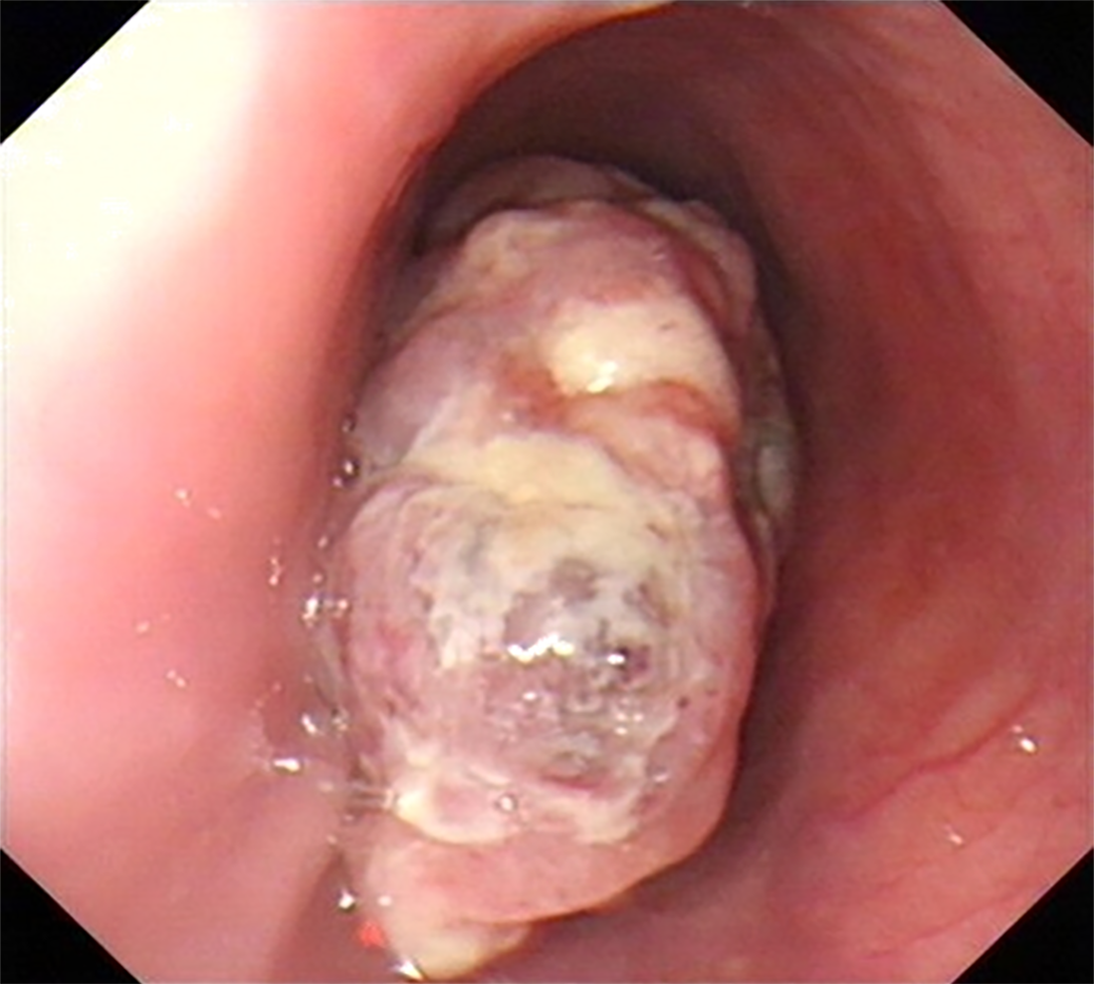

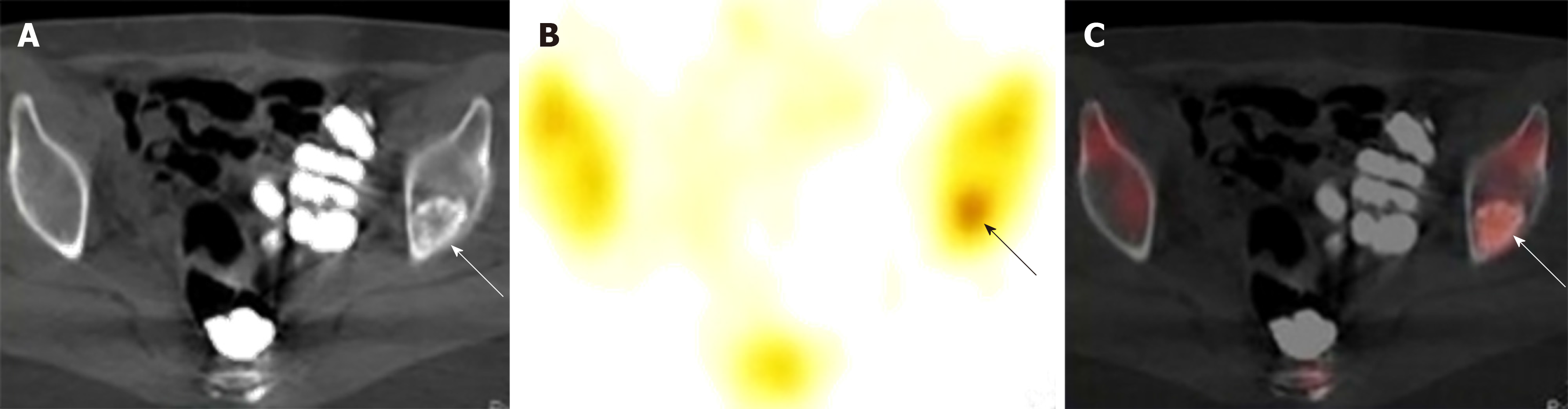

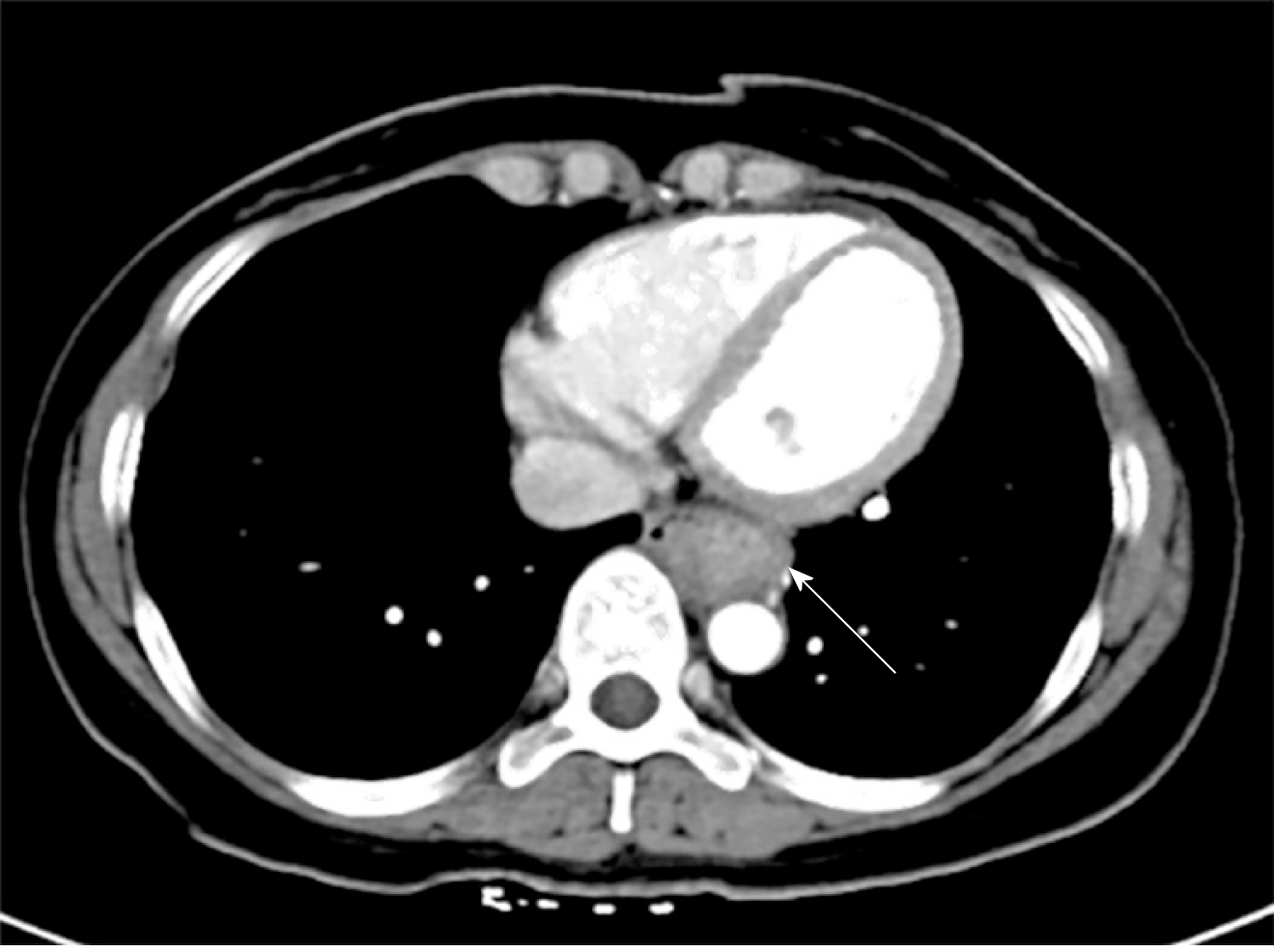

Upper gastrointestinal imaging revealed a polypoid intraluminal mass in the lower esophagus (Figure 1). Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a nonpigmented mass located 30-35 cm from the incisors, which existed as a protrusion of the esophagus wall and bleed upon contact (Figure 2). Single-photon emission computed tomography-computed tomography (SPECT/CT) fusion images confirmed the presence of a left iliac bone metastatic lesion (Figure 3). Thoracic contrast-enhanced CT revealed an enhancing mass in the lower esophagus; no enlarged lymph nodes were found within the scanning range (Figure 4).

Histological analysis of the biopsied mass showed that the lamina propria contained a large number of infiltrating heteromorphous cells and necrosis, indicating a malignant tumor (Figure 5). Immunohistochemical staining revealed that the tumor was negative for cytokeratin but positive for S-100, HMB-45, and melan-A. The percentage of Ki67- positive cells was about 60% (Figure 6). These findings supported the diagnosis of melanoma.

The final diagnosis of advanced primary amelanotic malignant melanoma of the esophagus was made according to the imaging and biopsy findings.

The patient was discharged to home after refusing palliative care. After discharge, she self-administered apatinib for 3 mo according to the instructions for drug use. She reported having discontinued the drug at this time because of the intolerable adverse reaction of dizziness, which was found by us to be caused by a sharp rise in blood pressure. There was no significant relief of her dysphagia following the drug withdrawal. However, when the patient underwent magnetic resonance imaging examinations at local hospitals, the esophageal lumen was found to be recanalized. The patient was then treated for 2 mo with an oral decoction (also self-administered) consisting of herba duchesnea indica, climbing nightshade, gentiana macrophylla, black nightshade, HERBA EPIMEDII, asiatic cornelian cherry fruit, solomonseal rhizome, fruit of glossy privet, unprocessed rehmannia root, herba celiptae, human placenta, Chinese angelica, glabrous greenbrier rhizome, grifola, etc., and took it frequently every day. The treatment was discontinued due to severe vomiting. No treatment for the melanoma has been used or administered since then.

The patient’s character was very optimistic and strong throughout the illness, which may be related to her police career. She told us that she was surprised to open her eyes every morning because she was still alive. She also reported that care from her family made her happy. She said she was eager to survive but was not afraid of death. She felt lucky that she had lived for so long in the case of this disease. From the time of diagnosis to writing this manuscript, the patient's survival period has reached 24 mo. During this period, the patient's condition fluctuated and hematemesis occurred occasionally. However, her overall condition was improved as compared with that experienced during the periods of drug treatment, and the patient was able to live independently.

Cases of PMME are rare, representing only 0.1%-0.2% of all esophageal malignancies reported[1]. Primary AMM of the esophagus is extremely rare, with only about 20 cases published in the literature to date. PMME has a very poor prognosis due to its high metastatic potential, reflected by its median survival time of 10 mo[6]. AMMs tend to be diagnosed at more advanced stages, making the overall survival lower than that of PMMs[5]. De La Pava et al[7] reported the presence of melanocytes within the esophageal mucosa in 1963. For a long time before this, esophageal malignant melanoma was considered to be a metastatic disease from other origins of malignant melanoma.

Currently, the average age of onset of PMME is 60.5 years old, and the ratio of male to female is 2:1[6]. Although risk factors have still not been defined, melanocytosis is considered a predisposing factor[1]; yet, there have been no reported cases of melanocytosis progressing to PMME[6]. The clinical symptoms of PMME are similar to those of other esophageal malignancies. Dysphagia is the most common, followed by retrosternal or epigastric discomfort or pain, while hematemesis or melena is uncommon. In more than 90% of the reported cases, the lesion itself occurs in the lower two-thirds of the esophagus[8].

Upper gastrointestinal radiography usually displays a polypoid intraluminal mass but significant obstruction is uncommon. Radiological examination is difficult to distinguish from other polypoid tumors, such as spindle cell carcinoma[9]. The typical endoscope visualization shows a polypoid lesion, accompanied rarely by ulcers. PMME is usually pigmented, and the endoscopically viewed characteristic black mass supports the diagnosis of PMME[10]. Because of the paramagnetic property of melanin, magnetic resonance images reveal pigmented melanomas by their distinctive 'short T1 and short T2 signals'[11]. Between 10% and 25% of cases are nonpigmented, and in most cases histological examination can detect melanin granules[12]. Primary AMM of the esophagus has no melanin granules detectable on histologic examinations, and they represent only 2% of all esophageal melanomas[3]. Without melanin, AMMs can hardly be distinguished from other nonpigmented tumors, such as poorly differentiated squamous carcinoma, sarcoma, carcinosarcoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma, by magnetic resonance and endoscopic images.

AMMs contain stage I and/or II melanosomes[13]. Immunohistochemical staining showing positivity for protein S-100, HMB-45, and melan-A and negativity for CK supports the diagnosis of malignant melanoma. PMME metastases are mainly hematogenous and lymphatic. At the time of diagnosis, approximately 50% of patients have metastatic lesions, involving the liver (31%), mediastinum (29%), lung (18%), and brain (13%)[12]. Thoracic and abdominal CT is helpful in defining mediastinal invasion, lymph node enlargement, and distant metastasis, and can be used to display and determine the stage of lesions. Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT also plays an important role in the diagnosis of metastatic lesions. In 2009, the American Joint Committee on Cancer developed a new staging system for upper gastrointestinal melanoma[14], according to which, our case which had developed metastasis to distant organs, was identified as stage IVc.

Due to the rarity of PMME cases, there is no specific standard for treating this malignancy. Esophagectomy is preferred for patients with localized lesions. However, there has been little effective treatment in the past for patients with metastatic melanoma because of the poor efficacy of traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy. It was not until the advent of ipilimumab in 2011 that immunotherapies and targeted therapies developed rapidly within a few years, significantly improving the overall survival of patients with advanced melanoma and overcoming its characterization as an incurable disease. Targeted therapies include inhibition of the melanoma-associated genes BRAF and MEK; indeed, BRAF/MEK inhibitor combinations have become a standard therapy for patients with BRAF V600-mutated metastatic melanoma[15]. BRAF is the most frequently mutated gene in melanoma[16]. On the other hand, BRAF mutations are rare in mucosal melanomas, including esophageal melanoma, and activating mutations of the cell surface receptor tyrosine kinase are discovered more frequently[17]. Imatinib is a targeted drug for such patients[17].

Blocking antibodies against cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4, and programmed death 1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) serve as immune checkpoint inhibitors; mechanistically, they promote the activation and proliferation of T cells, producing antitumor effects. The PD-1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab, in particular, are currently in use as first-line agents for advanced melanoma[15]. Talimogene laherparepvec is an oncolytic virus of melanoma, which can be applied as a therapy to dissolve tumor cells, release tumor-derived antigens, activate the immune system, and kill tumor cells[15]. However, studies on the efficacy of immunotherapy for mucosal melanoma are limited. It is also difficult to determine the value of these therapies for PMME patients due to the very small number of patients.

In our case, taking apatinib for 3 mo may have contributed to the prolongation of the patient's survival. Apatinib is a small molecule antiangiogenesis inhibitor, which remains an important therapeutic approach for advanced malignant melanoma. It has been shown that apatinib mesylate tablets can treat advanced malignant melanoma, with a relatively ideal therapeutic effect[18]. Of course, we should not rule out the contribution of Chinese medicine treatment to the survival of this patient. We also need to pay attention to the fact that the drug treatment time was only 5 mo in total. After that, the patient survived for 19 mo. The question then is, was survival due to drug efficacy alone?

As highlighted by the above therapies, immune system activity is key to controlling the occurrence and development of tumors. Before the emergence of ipilimumab, the median survival time for metastatic melanoma patients was only 6.2 mo[19]. For our patient, the post-diagnosis follow-up revealed the patient to be in a very bad condition during the periods of drug treatment. Her dysphagia did not improve, yet severe vomiting and hypertension occurred, she became extremely weak, and the treatment had to be stopped. Throughout, the patient held an optimistic attitude about her illness. She reported having forced herself to eat for 1 mo after stopping the drug, and her vomiting eased and condition improved. After that, she kept a regular bedtime every day and performed moderate outdoor exercise, housework and entertainment activities that made her feel happy. According to self-report, she did what she wanted to do, ate what she wanted to eat, avoided overwork, and maintained a balanced diet; her family cared for her. Although, after stopping all treatment, the disease status fluctuated and hematemesis occurred occasionally, her condition was improved compared with that during the periods of drug treatment, and the patient could basically live independently.

Epidemiological studies have indicated that psychological stress, chronic depression, and lack of social support may be closely related to cancer occurrence and development[20]. The chronic stress response and depression activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, leading to the release of mediators that inhibit certain parts of the immune response and impairing the most important effectors of the anti-tumor immune response; collectively, these effects generate conditions for the occurrence and progression of certain types of cancer[21]. It has been shown experimentally that psychological intervention can reduce recurrence and mortality in patients with malignant melanoma[21].

In addition to reports of the effects of negative emotions on cancer, a few researchers have studied the effects of positive emotions on cancer. The brain's reward system is known to regulate the antitumor immune response. Researchers have used chemical genetics (i.e., ‘Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs’, or 'DREADDs’) to activate the reward system of B16 melanoma-bearing mice, which led to reduced tumor weight. Some subsets of immune cells, such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), support tumor growth by inhibiting the antitumor immune response and by creating an enabling environment for the tumor. After activation of the reward system, the immunosuppressive effect of MDSCs becomes weakened and tumor growth is inhibited[22]. Since the activation of the brain's reward system mediates positive emotions, it can be inferred that a positive psychological state can impact the antitumor immune response.

The knowledge provided from our case is based on the fact that it represents an extremely rare case of primary AMM of the esophagus, which has a very bad prognosis in general, yet this patient's survival has been much longer than that of other metastatic melanoma patients. Unfortunately, there are myriad unknown but potentially confounding factors, other than the mental state, that may have affected the patient’s survival.

We present here an extremely rare case of primary AMM of the esophagus, which in general has a worse prognosis than pigmented malignant melanomas. Our patient's time of survival after diagnosis has been much longer than that of other metastatic melanoma patients who did not receive effective treatment, which may have been related to her positive mental state. Although psychological interventions cannot replace drug therapies nor be used as independent treatments for cancer, they seem to have beneficial effects on survival. It will be of great significance to perform systematic studies of whether the survival period of patients with metastatic melanoma may be extended through psychological intervention.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Elhamid SMA

S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Sun H, Gong L, Zhao G, Zhan H, Meng B, Yu Z, Pan Z. Clinicopathological characteristics, staging classification, and survival outcomes of primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. J Surg Oncol. 2018;117:588-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang X, Kong Y, Chi Z, Sheng X, Cui C, Mao L, Lian B, Tang B, Yan X, Si L, Guo J. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus: A retrospective analysis of clinical features, management, and survival of 76 patients. Thorac Cancer. 2019;10:950-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stringa O, Valdez R, Beguerie JR, Abbruzzese M, Lioni M, Nadales A, Iudica F, Venditti J, San Roman A. Primary amelanotic melanoma of the esophagus. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1207-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rochefort P, Roussel J, de la Fouchardière A, Sarabi M, Desseigne F, Guibert P, Cattey-Javouhey A, Mastier C, Neidhardt-Berard EM, de la Fouchardière C. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus, treated with immunotherapy: a case report. Immunotherapy. 2018;10:831-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Strazzulla LC, Li X, Zhu K, Okhovat JP, Lee SJ, Kim CC. Clinicopathologic, misdiagnosis, and survival differences between clinically amelanotic melanomas and pigmented melanomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1292-1298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Iwanuma Y, Tomita N, Amano T, Isayama F, Tsurumaru M, Hayashi T, Kajiyama Y. Current status of primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus: clinical features, pathology, management and prognosis. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:21-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bisceglia M, De La Pava S, Nigogosyan G, Pickren Jw, Cabrera A. Melanosis of the esophagus. Cancer. 1963;16:48-50. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Bisceglia M, Perri F, Tucci A, Tardio M, Panniello G, Vita G, Pasquinelli G. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus: a clinicopathologic study of a case with comprehensive literature review. Adv Anat Pathol. 2011;18:235-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gollub MJ, Prowda JC. Primary melanoma of the esophagus: radiologic and clinical findings in six patients. Radiology. 1999;213:97-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu H, Yan Y, Jiang CM. Primary Malignant Melanoma of the Esophagus With Unusual Endoscopic Findings: A Case Report and Literature Review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li P, Liu J. Diagnostic value of MRI and computed tomography in anorectal malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2016;26:46-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Machado J, Ministro P, Araújo R, Cancela E, Castanheira A, Silva A. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4734-4738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kobayashi J, Fujimoto D, Murakami M, Hirono Y, Goi T. A report of amelanotic malignant melanoma of the esophagus diagnosed appropriately with novel markers: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:9087-9092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang L, Zong L, Nakazato H, Wang WY, Li CF, Shi YF, Zhang GC, Tang T. Primary advanced esophago-gastric melanoma: A rare case. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:3296-3301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Luther C, Swami U, Zhang J, Milhem M, Zakharia Y. Advanced stage melanoma therapies: Detailing the present and exploring the future. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;133:99-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Langer R, Becker K, Feith M, Friess H, Höfler H, Keller G. Genetic aberrations in primary esophageal melanomas: molecular analysis of c-KIT, PDGFR, KRAS, NRAS and BRAF in a series of 10 cases. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:495-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tacastacas JD, Bray J, Cohen YK, Arbesman J, Kim J, Koon HB, Honda K, Cooper KD, Gerstenblith MR. Update on primary mucosal melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:366-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yang L, Zhu H, Luo P, Chen S, Xu Y, Wang C. Apatinib mesylate tablet in the treatment of advanced malignant melanoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:5333-5338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Korn EL, Liu PY, Lee SJ, Chapman JA, Niedzwiecki D, Suman VJ, Moon J, Sondak VK, Atkins MB, Eisenhauer EA, Parulekar W, Markovic SN, Saxman S, Kirkwood JM. Meta-analysis of phase II cooperative group trials in metastatic stage IV melanoma to determine progression-free and overall survival benchmarks for future phase II trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:527-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 513] [Cited by in RCA: 536] [Article Influence: 31.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Antoni MH, Lutgendorf SK, Cole SW, Dhabhar FS, Sephton SE, McDonald PG, Stefanek M, Sood AK. The influence of bio-behavioural factors on tumour biology: pathways and mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:240-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 760] [Cited by in RCA: 697] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Reiche EM, Nunes SO, Morimoto HK. Stress, depression, the immune system, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:617-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 762] [Cited by in RCA: 853] [Article Influence: 40.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ben-Shaanan TL, Schiller M, Azulay-Debby H, Korin B, Boshnak N, Koren T, Krot M, Shakya J, Rahat MA, Hakim F, Rolls A. Modulation of anti-tumor immunity by the brain's reward system. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |