Published online Oct 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i19.3082

Peer-review started: June 3, 2019

First decision: August 1, 2019

Revised: August 11, 2019

Accepted: August 27, 2019

Article in press: August 27, 2019

Published online: October 6, 2019

Processing time: 124 Days and 19.6 Hours

Hypoplasia of bilateral cruciate ligaments is a rare congenital malformation. The diagnosis of such diseases and indications for the various treatment options require further analysis and discussion.

The patient is a 26-year-old Chinese woman who has been suffering from knee pain since the age of 8 years, 2-3 episodes a year. Three years ago, due to the practice of advanced yoga poses, the frequency of left knee pain increased, requiring prompt medical treatment. Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated an absence of both anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments of both knees with abnormal posterior tilting of the tibial plateau. Bilateral subluxation of the knee joint was also found, therefore tibial osteotomy was performed. The patient reported at the 24 mo follow-up that the frequency of pain and instability had been reduced and function restored.

Osteotomy may be an effective method to treat patients with congenital cruciate ligament deficiency with posterior tibial plateau tilting. The diagnosis of congenital cruciate ligament deficiency shall be based on the combination of patient’s medical history, clinical manifestations, and findings from imaging to avoid possible misdiagnosis. Based on the symptoms, frequency of attacks, and intent of the individual, appropriate treatment options shall be identified.

Core tip: While some articles reported the rare disease of congenital absence of cruciate ligaments, to our knowledge none of them systematiclly reports the published cases and summarizes the characteristics of this kind of disease. . We conducted a literature review that focus on the symptoms and their appear age of the disease. In order to find out the best treatment programs for congenital absence of cruciate ligaments, we also paid great attention to the treatment method of each case. In addition, we concluded a diagnostic process that will help clinicians to decrease the chance of misdiagnosis.

- Citation: Lu R, Zhu DP, Chen N, Sun H, Li ZH, Cao XW. How should congenital absence of cruciate ligaments be treated? A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(19): 3082-3089

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i19/3082.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i19.3082

In 1962, Giorgi[1] first described congenital anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) deficiency. In general, this form of congenital dysplasia is unilateral, rarely being observed in both knee joints[2,3]. It involves defects of the anterior or posterior cruciate ligament, or both, and may include a single, or both, knees[4]. Such patients are extremely rare, with a prevalence of 0.017 per 1000 live births[5,6], especially when both the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments of each knee are missing combined with tibial plateau dysplasia[7].

As yet, there is no clear consensus on the treatment of such diseases. For some patients without apparent knee instability or pain, and without symptoms that affect daily life, some clinicians have often observed that cruciate ligament reconstruction offers no improvement[8,9]. These clinicians therefore suggest conservative treatment for asymptomatic patients. For those who are symptomatic, in order to regain knee stability and function, most clinicians are reported to proceed with cruciate ligament reconstruction or orthopedic surgery[9-11]. In this case, because of the large tilt of the tibial plateau, the surgeon decided to first correct the bony deformity. Therefore, tibial osteotomy was adopted. After 2 years of follow-up, the effect of treatment was found to be excellent. The case report on this patient follows.

A 26-year-old Chinese woman presented with occasional alternating pain in her knees from being about 8 years old, regularly occurring 2-3 times a year.

Her pain was relieved after rest. The left knee was unstable. About three years prior to presentation in the clinic, the frequency of alternating pain in both knees increased to 10-12 times a year, coinciding with practicing advanced yoga, each period of pain lasting approximately a week. After she attended an outpatient clinic, she was provided nonoperative treatment, such as Chinese massage or acupuncture, for a year.

Neither she nor her family had any past history of congenital knee deformity.

There was no obvious swelling of either knee joint during physical examination. The joints were flexed from 0° to 120° with no apparent tenderness, and tibial movement was normal. Anterior and posterior drawer tests were positive as well as Lachman test. The Lysholm II score was 72.

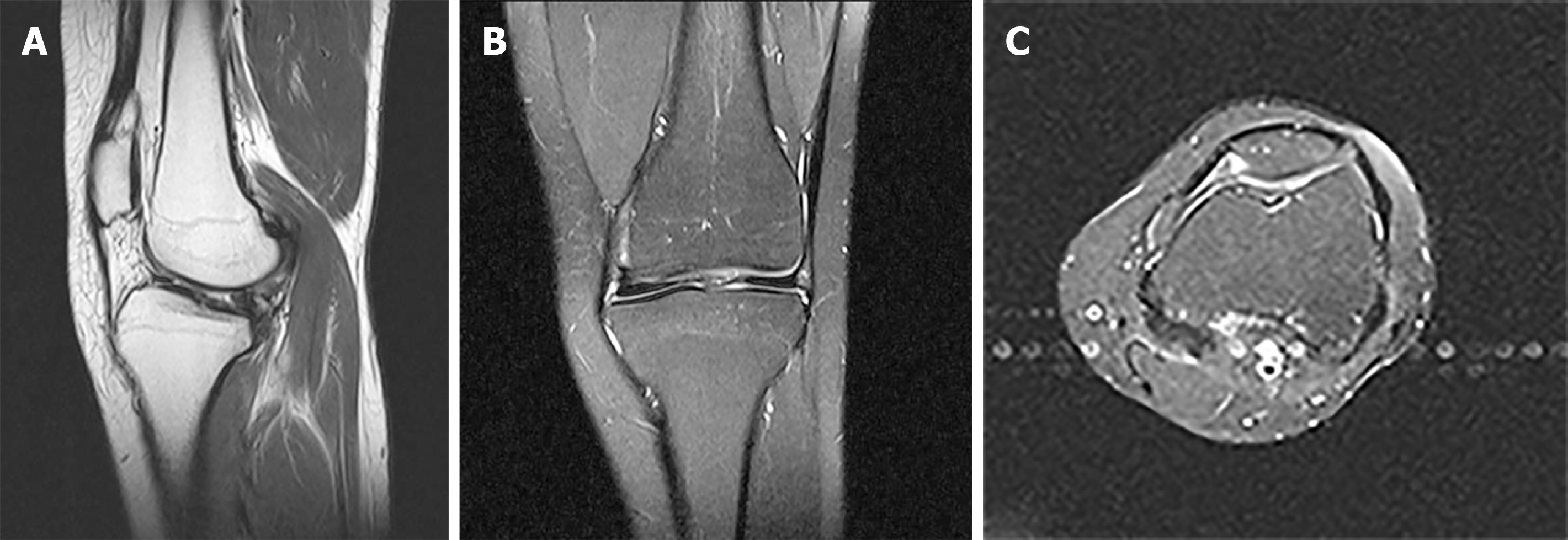

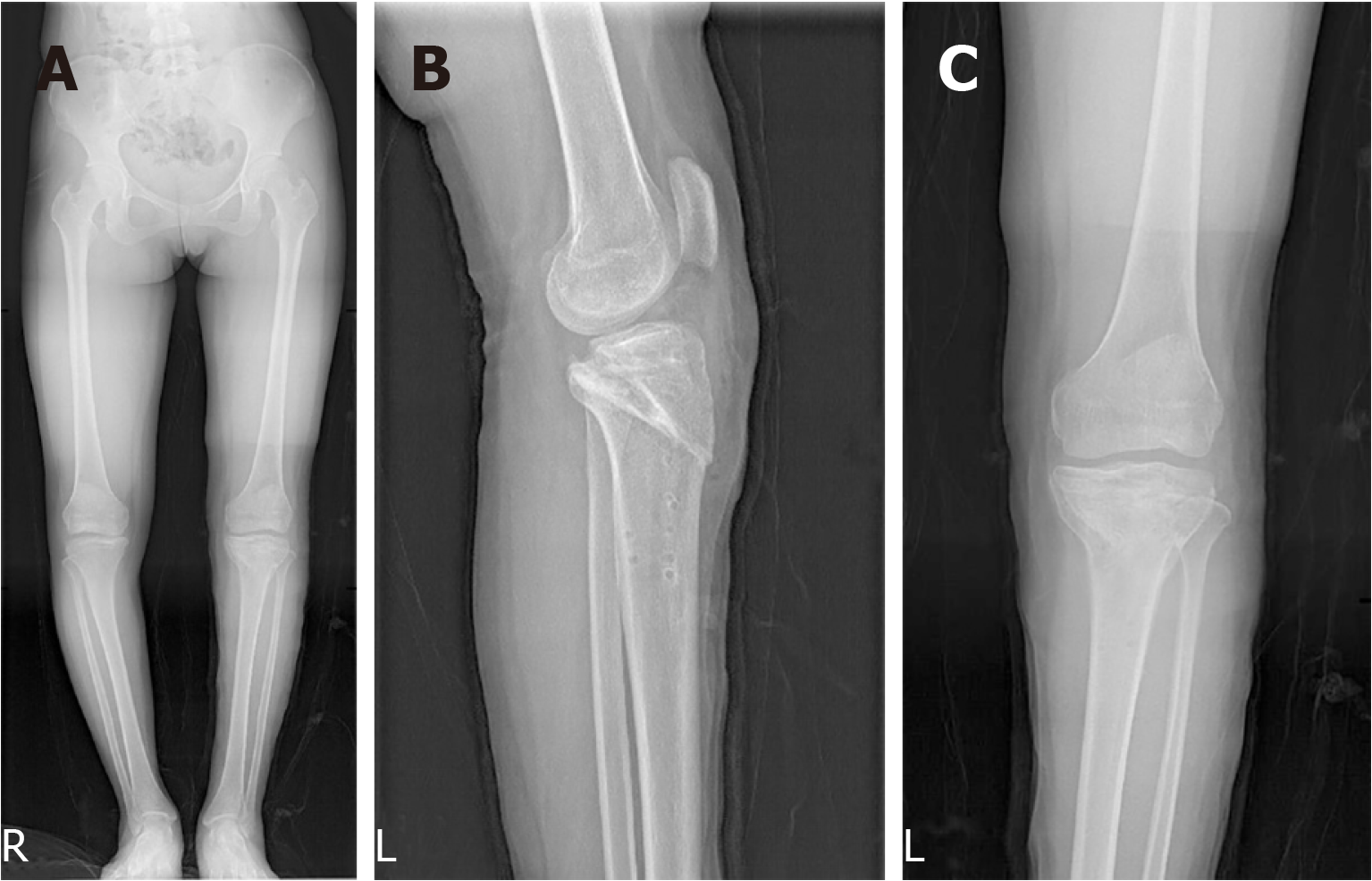

An X-ray showed bilateral varus knee with instability (Figures 1A and 1B). An magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (Figure 2) indicated bilateral knee joint malalignment, anterior displacement of the tibia, subluxation, left tibial plateau bone cysts, sclerosis and bone formation, a slightly worn right medial tibial plateau, an absence of ligaments in both knees, bilateral thickening of the lateral retinacula, and bilateral patellar joint malalignment with grade III-IV wear in the patella and patellofemoral joint.

Congenital cruciate ligament deficiency (bilateral knee joints).

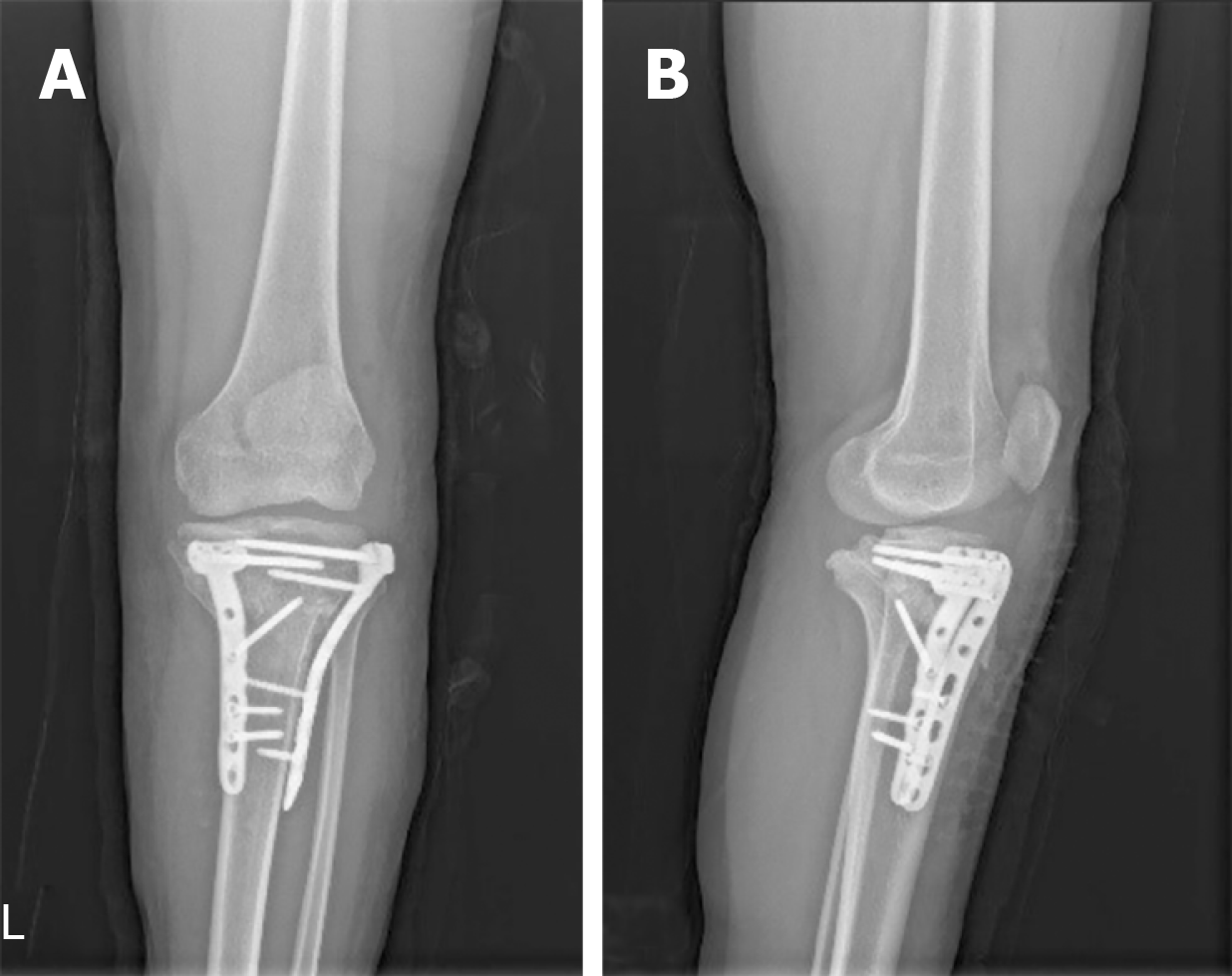

The patient underwent osteotomy of the left proximal tibial under general anesthesia, with internal tibial fixation (Figures 3A-D). Large tilt of the tibial plateau was corrected (Figure 3B). Neutral left lower limb alignment was attained (Figure 3C). Postoperative recovery was positive with the patient's regular reviews.

Eleven months postoperatively, X-ray examination demonstrated that the left knee was in good alignment, and correction to the left tibial plateau and proximal tibia had been achieved with no loose internal fixation. The left knee was able to achieve flexion of 0° to 120°. The tibial internal fixation device was removed under general anesthesia following tracheal intubation (Figure 4A-C).

After 24 mo of follow-up visits, the patient felt that function of the left knee was better than the right. She was not restricted in activities by the left knee, being able to squat completely, with no pain at rest. Slight pain would occur after a long walk which fortunately had no impact on work or life activities. The Lysholm II score was 88.

There is still controversy in the literature regarding treatment of congenital absence of cruciate ligaments[9,10]. In this case, the patient was treated with tibial osteotomy. Although satisfactory results were obtained, they may only be applicable to this case.

Congenital cruciate ligament defect is a very rare disease with an incidence of only 17 per million population[5]. In most cases previously described in the literature, congenital absence of the cruciate ligaments is usually associated with musculoskeletal diseases, in particular incomplete or stunted development of the lower limbs such as the femur, tibial spine, tibia, fibula or sacrum, congenital meniscus malformations, and multiple organ syndromes such as thrombocytopenia-absent radius syndrome[3,12]. With regard to the congenital absence of a cruciate ligament usually being in combination with other congenital musculoskeletal diseases, the literature has noted that the main role of the intercondylar notch is to adapt to the cruciate ligament[1,13]. Therefore, in the absence of a ligament, formation of the intercondylar notch will be affected. However, some authors believe that the development of the intercondylar spine in the proximal humerus depends on the presence of the cruciate ligament[14]. Therefore, if the ligament is congenitally absent, iliac spine dysplasia will eventually occur. Others believe that malformation is caused by congenital dysplasia rather than through the association with cruciate ligament development[15,16].

History: Following a review of previously published literatures, it has been ascertained that about 31% of patients start experiencing pain and instability due to trauma[7,10,17,18]. The literatures suggests that if trauma is reported in a patient’s history but no significant abnormality of the contralateral knee is observed, misdiagnosis of congenital absence of a ligament may occur instead of post-traumatic ligament loss. Symptoms of congenital ligament absence begin with mild trauma or sprains, ultimately leading to an imbalance in the soft tissue of the knee. In this case, the patient experienced painful symptoms in the knees after practicing advanced yoga exercises. Although there was no apparent history of trauma, there was a clear incentive. In addition, in patients with non-healing osteophytes, injury caused by trauma is more likely to result in fractures at the epiphysis or long bone, or intercondylar eminence avulsion, so cruciate ligament rupture in such patients is unlikely[8]. It has also been proposed that the possibility of congenital absence of a ligament in young patients with a history of trauma and loss of a ligament should not be neglected, and a differential diagnosis should carefully be performed. For those patients who often complain of instability after a traumatic event[7], the clinician should objectively distinguish the real degree of laxity and the patient’s own sense of instability through a positive clinical examination[19]. The history of young children should be scrutinized very closely to ascertain if there were signs of congenital abnormalities, because a history of trauma did not rule out congenital absence of a ligament.

Symptoms: A search of the literature resulted in the discovery of cases of congenital absence of ligaments in a total of 41 knees. Only 13% had no apparent symptoms. The other knees suffered varying degrees of pain with lower limb instability. According to our results, a vast majority of patients have onset of the condition in the 5-20 years old age group and are mostly adolescents. At present, no elderly patients with congenital absence of a ligament have been found. The literatures point out that some patients may not have any symptoms (patients with absence or incompetence in a cruciate ligament often do not complain about joint instability), because they may have adapted to those pathological anatomical conditions[10,20]. However, with age or after sudden trauma, the balance of the knee for which the patient has already compensated is destroyed, causing knee instability, recurrent dislocation, and even pain and other symptoms that accelerate the progression of knee osteoarthritis[21].

In addition, it has been speculated that patients with congenital absence of an ACL may not be detected and need no intervention because, unlike traumatic ACL injuries, they can adapt during development and will not experience subjective instability[5]. This adaptation can delay the onset of osteoarthritis caused by chronic laxity compared to traumatic tears. It is known that patients with congenital absence of ligaments may be asymptomatic, but if symptoms appear at a young age, it is less likely that they will reoccur at an older age[8]. This suggests that we shall consider the diagnosis of congenital ligament loss in young patients during clinical work.

Signs: A review of all cases demonstrated that although some patients did not have apparent symptoms or did not feel unstable on their own, all patients had positive signs of varying degrees of lack of ligament tissue. These positive signs included Lachman test, pivotal transfer test, and anterior and posterior drawer test. Some patients might demonstrate varying degrees of knee effusion, knee cartilage damage, meniscal tears, with medial or lateral collateral ligament injuries due to prolonged knee instability, positive floating blister test, McMurray test, squeezing abrasion test, or eversion. Corresponding positive signs such as varus stress relaxation were also observed. A thorough physical examination of the knee should still be conducted in the clinic to ascertain the patient’s chief complaint in order to facilitate symptomatic treatment.

Videography: Imaging is our primary means of diagnosing such diseases. In clinical practice, radiologists often find it difficult to distinguish between traumatic loss and congenital absence of a cruciate ligament. Cases show that if trauma is reported in a patient’s history and the contralateral knee is normal, and if arthroscopic and MRI reports do not focus on femoral intercondylar or zygomatic spinal deformities (X-rays show an abnormality of the sacrum, with only one bump in the sacrum, possibly a sign of cruciate ligament dysplasia), the correct diagnosis may be missed. Therefore, when using imaging to judge between congenital instability and post-traumatic instability, it shall be ascertained whether the joint bones in the knee are deformed.

For diagnosis using imaging, plain film can be used to perform a preliminary diagnosis of patients with congenital ligament loss according to the three-tiered classification of Manner et al[6]. According to the authors’ conclusions, the differentiation of trauma and underdevelopment of one or two cruciate ligaments can be determined based on the difference in the gap width index and height, and changes in the lateral and/or medial spinous processes of the tibia. In short, X-rays show several signs of radiology such as dysplasia of the tibial eminence, dysplastic lateral femoral condyle, or narrow intercondylar fossa, suggesting the possibility of congenital absence of a cruciate ligament[1,13,22].

Congenital absence of a cruciate ligament has been reported as a solitary abnormality or as part of a syndrome. Studies involving congenital syndromes (where ACL defects are common findings) have partially focused on correcting angle deformities, limb extensions, or amputations and prosthetic limb assembly. Reference is made to the treatment of cruciate ligament loss, but there are also significant differences in the postoperative outcome in different patients who have the same treatment[4,23,24]. Studies have also shown that instability of the anterior part of the knee can induce many forms of late lesion, such as meniscal tears or cartilage damage, which may also lead to the development of early arthritis. Even selective meniscectomy increases joint instability[7,25,26]. Therefore, we have summarized the treatment plans of patients who have had satisfactory treatment of this disorder in the literature, to provide a reference for clinicians to develop treatment strategies in the future. We reviewed 10 articles with a total of 41 patients. Of these, 24% of the knees were reconstructed, 16% were treated with limb orthosis, 12% were both reconstructed and provided with limb orthosis, and the remainder were treated conservatively.

For patients with no apparent symptoms or low frequency of pain and instability, conservative strategies such as strengthening the knee-related muscle groups are recommended. When Gabos et al[11] dealt with such patients, if the symptoms were caused by meniscal tears and cartilage damage (i.e. pain and joint effusions), only the joints were treated. For traumatic injury, after an average follow-up of 31 mo, the patients did not have any reduction in their capacity to exercise and could continue daily activities without further treatment. Such clinical follow-up results also confirmed their point of view that patients had tolerated joint laxation prior to trauma, and once the cause of pain had been eliminated, adequate muscle strengthening was sufficient.

For patients with symptoms of instability either with or without walking pain but without knee joint deformity, combined with the consent of the patient, treatment by cruciate ligament reconstruction was performed. Restoring the stability of the knee joint can further reduce the pain caused by instability of the knee joint and delay the progression of knee osteoarthritis.

For patients with unstable, painful symptoms and bony knee deformities that prevent adding an anterior or posterior cruciate ligament without it being damaged, it is recommended to first correct the bony deformity and ascertain whether, during the follow-up period, the patient is willing to undergo posterior ligament reconstruction. If the patient can achieve satisfactory knee stability and undergo daily activities following rehabilitation exercises, cruciate ligament reconstruction shall not be considered at that time. If noticeable symptoms of instability are still apparent, reconstruction of the cruciate ligament shall be considered. In this case, because the tibial plateau was tilted backwards (Figure 1B), if the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments had been reconstructed first, the reconstructed cruciate ligaments would have been subjected to a greater tension than in a normal knee joint, resulting in a high risk of failure of ligament fractured. Therefore, the surgeon first performed a tibial osteotomy to correct the skeletal deformity. After a period of observation, cruciate ligament reconstruction was considered. We agree with De Ponti et al[7] that in the treatment of ligamentous dysplasia, factors such as age, type of boney protrusions, activity level, and the quality and quantity of symptoms should be considered. Cruciate ligament reconstruction should be limited to cases of impaired joint stability and objectively manifested as a frequent dysfunction. Surgical indications are also based on the patient's condition and expectations and should only be considered after appropriate counseling. Summary of published studies regarding cruciate ligament aplasia sees Table 1.

| Author | Year (yr) | Symptom age | Symptoms | History of trauma | Treatment |

| Katz et al[18] | 1967 | 4 patients at 4 Y, 1 patient at 9 Y | 5 patients felt I | N | 5 patients both O and LR |

| Thomas et al[27] | 1985 | 12 patients at 2-16 Y | 6 patients felt I, 6 patients had no symptoms | N | 5 patients O, 7 patients C |

| Kaelin et al[28] | 1986 | 6 patients at 9-22 Y | 6 patients felt I | 2 patients H, 4 patients N | 6 patients C |

| De Ponti et al[7] | 2001 | 2 patients at 11 Y | 1 patient felt I and P, 1 patient feel I | 1 patient H, 1 patient N | 2 patients C |

| Gabos et al[11] | 2005 | 4 patients at 14-17 Y | 4 patients feel I | Not mentioned | 4 patient LR |

| Ergün et al[14] | 2008 | 1 patient at 3 Y | 1 patient felt I | N | 1 patient LR |

| Kwan et al[29] | 2009 | 3 patients at 38, 7, and 4 Y | 1 patient felt P, 2 patients felt I | N | 3 patients C |

| Sonn et al[17] | 2014 | 2 patients at 11 and 4 Y | 2 patients feel I and P | 2 patients H | 1 patient LR, 1 patient O |

| Bedoya et al[4] | 2014 | 2 patients at 13 Y | 2 patients felt I and P | Not mentioned | 2 patients LR |

| Davanzo et al[10] | 2017 | 2 patients at 6 Y, 2 patients at 15 Y | 4 patients felt I and P | 1 patient H, 3 patients N | 2 patients LR, 2 patients C |

| Total | 41 patients at 2-38 Y, children and young people | 1 patient felt P; 9 patients felt I and P; 26 patients felt I; 6 patients had no symptom, accounting for 14% | 26 patients N; 6 patients not mentioned; 9 patients H, accounting for 31% | 10 patients LR; 6 patients O; 5 patients both O and LR; 20 patients C |

We believe that the treatment of this disease should take into account different factors, namely, the patient’s age, type of dysplasia and level of their activity, and most importantly, the extent of the symptoms and frequency of attacks. We attribute a crucial role to the frequency and type of symptom experienced because we believe that surgical methods shall be used with caution in cases of related joint instability.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Georgiev GP, Anand A S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Giorgi B. Morphologic variations of the intercondylar eminence of the knee. Clin Orthop. 1956;8:209-217. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Barrett GR, Tomasin JD. Bilateral congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament. Orthopedics. 1988;11:431-434. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Mavrodontidis AN, Zalavras CG, Papadonikolakis A, Soucacos PN. Bilateral absence of the patella in nail-patella syndrome: delayed presentation with anterior knee instability. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:e89-e93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bedoya MA, McGraw MH, Wells L, Jaramillo D. Bilateral agenesis of the anterior cruciate ligament: MRI evaluation. Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44:1179-1183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Degnan AJ, Kietz DA, Grudziak JS, Shah A. Bilateral absence of the cruciate ligaments with meniscal dysplasia: Unexpected diagnosis in a child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Imaging. 2018;49:193-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Manner HM, Radler C, Ganger R, Grill F. Dysplasia of the cruciate ligaments: radiographic assessment and classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:130-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | De Ponti A, Sansone V, de Gama Malchèr M. Bilateral absence of the anterior cruciate ligament. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:E26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | DeLee JC, Curtis R. Anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;112-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sachleben BC, Nasreddine AY, Nepple JJ, Tepolt FA, Kasser JR, Kocher MS. Reconstruction of Symptomatic Congenital Anterior Cruciate Ligament Insufficiency. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39:59-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Davanzo D, Fornaciari P, Barbier G, Maniglio M, Petek D. Review and Long-Term Outcomes of Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction versus Conservative Treatment in Siblings with Congenital Anterior Cruciate Ligament Aplasia. Case Rep Orthop. 2017;2017:1636578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gabos PG, El Rassi G, Pahys J. Knee reconstruction in syndromes with congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:210-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Héron D, Bonnard C, Moraine C, Toutain A. Agenesis of cruciate ligaments and menisci causing severe knee dysplasia in TAR syndrome. J Med Genet. 2001;38:E27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Waxenbaum EB, Hunt DR, Falsetti AB. Intercondylar eminences and their effect on the maximum length measure of the tibia. J Forensic Sci. 2010;55:145-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ergün S, Karahan M, Akgün U, Kocaoğlu B. [A case of multiple congenital anomalies including agenesis of the anterior cruciate ligament]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2008;42:373-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Deroussen F, Hustin C, Moukoko D, Collet LM, Gouron R. Osteochondritis dissecans of the lateral tibial condyle associated with agenesis of both cruciate ligaments. Orthopedics. 2014;37:e218-e220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Walker JL, Milbrandt TA, Iwinski HJ, Talwalkar VR. Classification of Cruciate Ligament Dysplasia and the Severity of Congenital Fibular Deficiency. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39:136-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sonn KA, Caltoum CB. Congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament in monozygotic twins. Int J Sports Med. 2014;35:1130-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Katz MP, Grogono BJ, Soper KC. The etiology and treatment of congenital dislocation of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1967;49:112-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Balke M, Mueller-Huebenthal J, Shafizadeh S, Liem D, Hoeher J. Unilateral aplasia of both cruciate ligaments. J Orthop Surg Res. 2010;5:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cerulli G, Amanti A, Placella G. Surgical treatment of a rare isolated bilateral agenesis of anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments. Case Rep Orthop. 2014;2014:809701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hu J, DU SX, Huang ZL, Xia X. Bilateral congenital absence of anterior cruciate ligaments associated with the scoliosis and hip dysplasia: a case report and review of the literature. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123:1099-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Laor T, Jaramillo D, Hoffer FA, Kasser JR. MR imaging in congenital lower limb deformities. Pediatr Radiol. 1996;26:381-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lee YS, Chun DI, Park MJ. Bilateral PCL hypoplasia resulting in posterior, posterolateral rotatory instability and tears of the lateral meniscus anterior horn. Orthopedics. 2010;33:924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rainio P, Sarimo J, Rantanen J, Alanen J, Orava S. Observation of anomalous insertion of the medial meniscus on the anterior cruciate ligament. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:E9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jackson DW, Jennings LD, Maywood RM, Berger PE. Magnetic resonance imaging of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:29-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Silva A, Sampaio R. Anterior lateral meniscofemoral ligament with congenital absence of the ACL. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:192-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Thomas NP, Jackson AM, Aichroth PM. Congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament. A common component of knee dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:572-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kaelin A, Hulin PH, Carlioz H. Congenital aplasia of the cruciate ligaments. A report of six cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68:827-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kwan K, Ross K. Arthrogryposis and congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament: a case report. Knee. 2009;16:81-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |