Published online Oct 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i19.3055

Peer-review started: April 15, 2019

First decision: August 1, 2019

Revised: August 14, 2019

Accepted: August 27, 2019

Article in press: August 27, 2019

Published online: October 6, 2019

Processing time: 170 Days and 0.3 Hours

Monoclonal immunoglobulin can cause renal damage, with a wide spectrum of pathological changes and clinical manifestations without hematological evidence of malignancy. These disorders can be missed, especially when combined with other kidney diseases.

A 61-year-old woman presented with moderate proteinuria with normal renal function. She was diagnosed with IgA nephropathy combined with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance after the first renal biopsy. Although having received immunosuppressive treatment for 3 years, the patient developed nephrotic syndrome. Repeated renal biopsy and laser microdissection/mass spectrometry analysis confirmed heavy chain amyloidosis. After nine cycles of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone, she achieved very good partial hematological and kidney responses.

Renal injury should be monitored closely in monoclonal gammopathy patients without obvious hematological malignancy, especially in patients with other pre-existing renal diseases.

Core tip: Monoclonal immunoglobulin can cause renal injury without hematological evidence of malignancy. These disorders can be missed, especially when combined with other kidney diseases. We present a patient initially diagnosed with IgA nephropathy and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). Atypical characteristics and treatment refractoriness of IgA nephropathy led to a second renal biopsy. Amyloidosis was revealed, and laser microdissection/mass spectrometry was used for typing. The patient improved well after therapy containing bortezomib. Renal involvement should be monitored closely in patients with MGUS, especially in those with pre-existing kidney diseases.

- Citation: Wu HT, Wen YB, Ye W, Liu BY, Shen KN, Gao RT, Li MX. Underlying IgM heavy chain amyloidosis in treatment-refractory IgA nephropathy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(19): 3055-3061

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i19/3055.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i19.3055

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is found in 3%-4% of the population, especially in elderly people[1,2]. MGUS can progress to renal damage without evidence of hematological malignancy[3]. Renal involvement is then easily missed, especially when combined with underlying kidney diseases. We present a 61-year-old woman who was diagnosed with IgA nephropathy and MGUS after the first renal biopsy and other detailed examinations. The renal injury aggravation exacerbated, despite 3 years of aggressive treatment. Repeated renal biopsy discovered underlying heavy chain amyloidosis.

A 61-year-old woman was hospitalized for the second time for gradually aggravated lower limb edema on February 21, 2017.

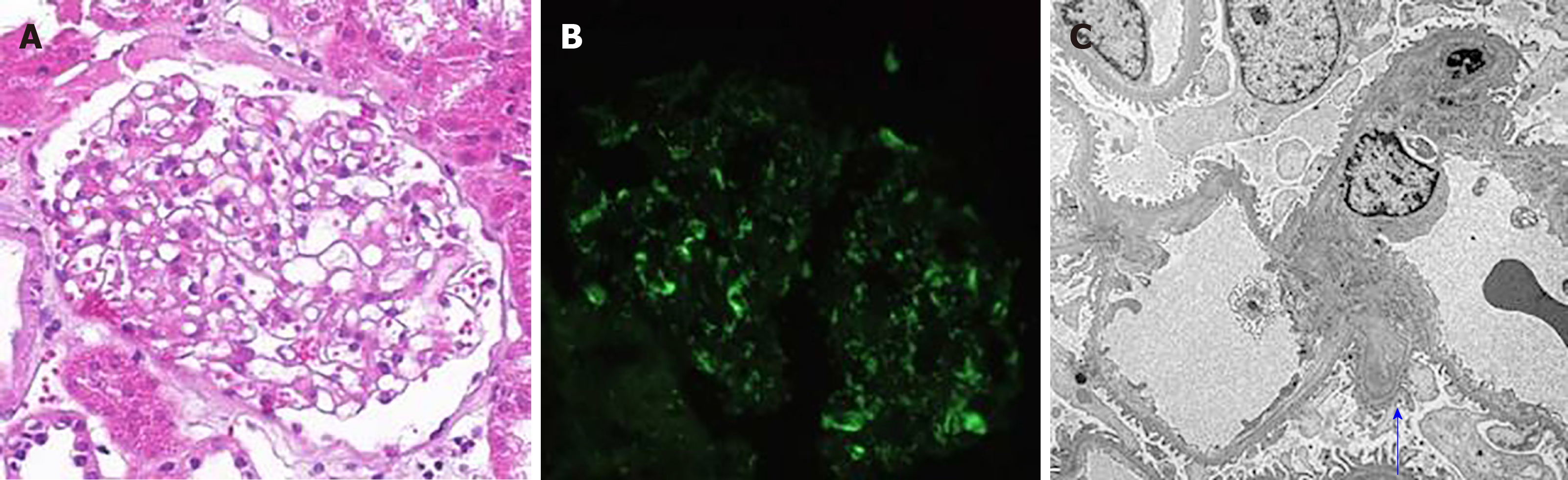

The patient was admitted 3 years ago because of moderate proteinuria. Urine protein excretory rate (UPER) was 1.91 g/24 h, and urine sediment showed no hematuria. Serum creatinine and albumin were normal. A monoclonal serum immunoglobulin M lambda (IgMλ) was found without evidence of hematological diseases. Blood pressure (BP) was low to normal. The patient underwent renal biopsy. Mild increased mesangial matrix and mesangial hypercellularity were observed under light microscopy. Immunofluorescence microscopy showed moderate positive signals for IgA in the mesangial area of all observed glomeruli, while other immunoglobulin heavy chains, immunoglobulin light chains and Congo red staining were negative. In electron microscopy, electron-dense deposits were observed in the paramesangium (Figure 1). No specific fibrils were seen in the mesangial area, glomerular basement membrane (GBM) and arterioles. The patient was diagnosed with IgA nephropathy combined with MGUS. She was intolerant to renin-angiotensin system inhibitors (RASIs) because of relatively low BP. Therefore, prednisone and Tripterygium wilfordii were given. UPER decreased to an average 1.5 g/24 h in the first 6 mo, but increased to 2-3 g/24 h after 1 year. Cyclophosphamide (cumulative dosage 12 g) and tacrolimus (FK506 concentration 5.7 ng/mL) were prescribed successively. However, lower limb edema was gradually aggravated. The patient was also followed up regularly in the hematology clinic, and the diagnosis of IgMλ MGUS was maintained.

The patient had normal BP and moderate pitting edema in the lower limbs. There was no enlargement of superficial lymph nodes, liver or spleen. She had no significant past or family history.

Laboratory tests revealed a normal complete blood count. UPER was 4.5 g/24 h, serum albumin was 24 g/L, and serum creatinine was normal. Differences between involved and uninvolved serum immunoglobulin free light chain levels (dFLC) was 56.3 mg/L. Thoracic and abdominal computed tomography and bone marrow biopsy were normal.

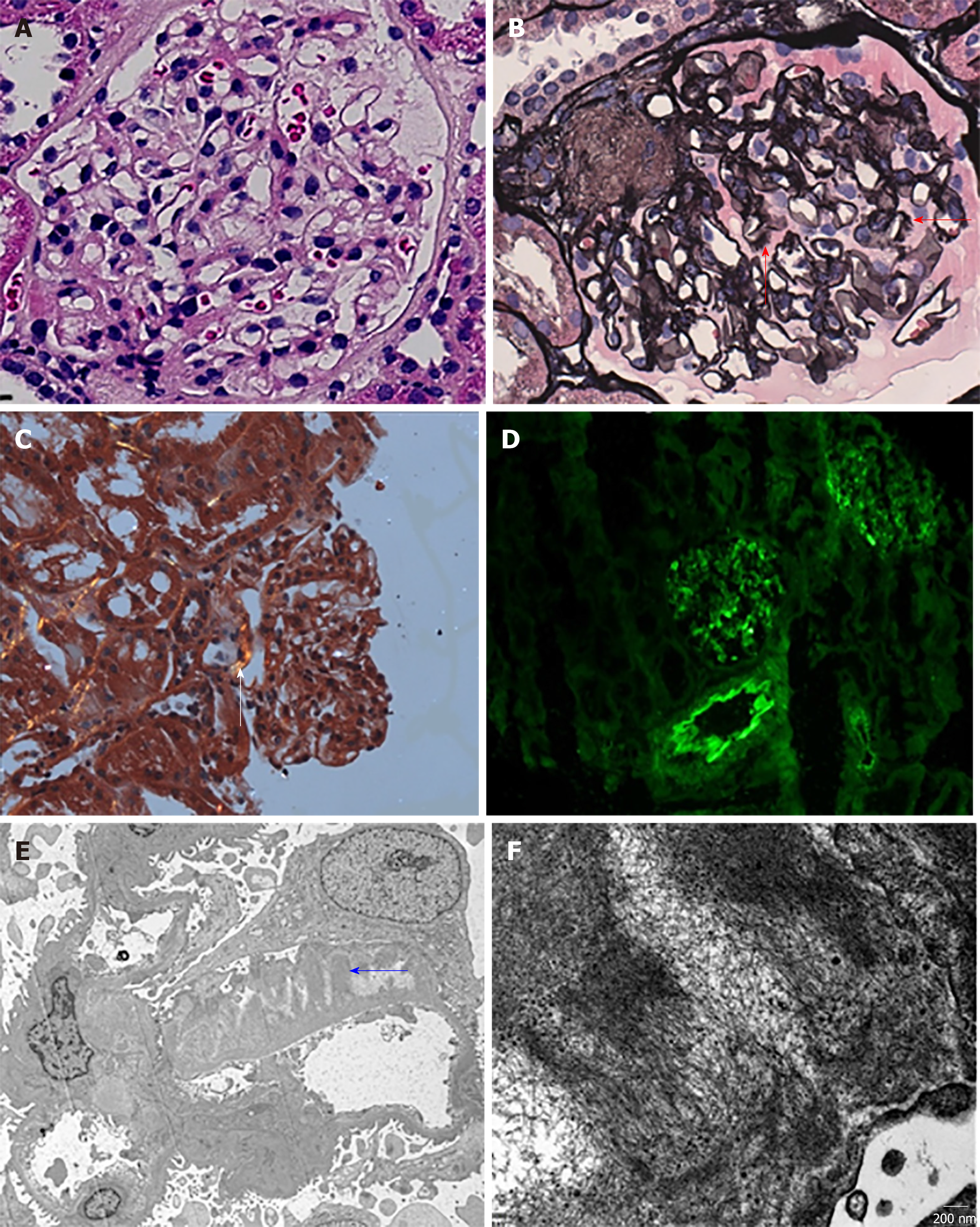

The repeated kidney biopsy specimen had 18 glomeruli. In light microscopy, mild pale eosinophilic material in the mesangium was found, but mesangial hypercellularity was not obvious. There was marked diffuse thickening of GBM, with subepithelial fringe-like projections. The tubulointerstitium had no significant changes. Arterioles were Congo red positive, with pathognomonic apple green birefringence under polarized light. In light microscopy, diffuse mesangial deposits of IgM, κ and λ were detected. IgA was detected by immunohistochemical staining. In electron microscopy, 8-12-nm diameter, nonbranching fibrils were deposited in the mesangial area, GBM and arterioles (Figure 2). There were also a few electron-dense deposits in the mesangial area. Renal amyloidosis and IgA nephropathy were coexistent. Laser microdissection/mass spectrometry (LMD/MS) analysis of the Congo-red-positive area confirmed heavy chain amyloidosis (μ chain). We performed LMD/MS on the first renal biopsy specimen, and found no evidence of amyloidosis.

The final diagnosis of the presented case is renal amyloidosis and IgA nephropathy.

Immunosuppressants were replaced by the combination of intravenous (iv) bortezomib 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, 15 and 22, cyclophosphamide 270 mg/m2 iv on days 1, 8 and 15, and dexamethasone 40 mg iv on days 1, 8, 15 and 22 for nine cycles.

The patient achieved very good partial hematological and kidney responses. At the last follow-up, UPER was 1.6 g/24 h, serum albumin was 31 g/L, and creatinine was still normal. Serum and urinary immunofixation electrophoresis both turned negative, and dFLC fell from 56.3 to 9.8 mg/L.

The patient was diagnosed with IgA nephropathy combined with IgMλ MGUS after detailed investigation 3 years ago. Since MGUS can progress to hematological malignancy, the patient was followed up regularly in both hematology and nephrology clinics. Kyle et al[4] identified 1,384 MGUS patients diagnosed at the Mayo Clinic from 1960 to 1994. During 11,009 person-years of follow-up, MGUS progressed in 115 patients to multiple myeloma and other disorders. IgM MGUS represents about 15% of all MGUS cases, and has increased risk of progression to malignancy compared with other subtypes[5]. In a study with long-term follow-up, about 14% of the patients with IgM MGUS developed malignancies, the majority of which were non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia[6]. No such disorders were discovered in our patient. However, the aggravated proteinuria, despite aggressive treatment for IgA nephropathy, urged us to find an underlying disorder. Amyloidosis was diagnosed by repeated renal biopsy.

Rarely, IgM MGUS can progress to renal limited injury, as in the present case. Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance (MGRS) was proposed by multinational and multidisciplinary cooperations in 2012 to emphasize those patients with renal damage caused by monoclonal immunoglobulin (MIg) secreted by small B cell clones[3]. These patients do not meet the diagnostic criteria for malignancy mentioned above. The spectrum of MGRS varies widely according to characteristics of pathogenic MIg, which can deposit in kidneys in the form of fibrils, microtubules, crystals, inclusions or nonorganized deposits/inclusions. Renal amyloidosis is most well-known among the different types of MGRS. Renal biopsy can help confirm renal involvement from MIg and identify different pathological types. Although monoclonal gammopathy is suggested to increase the risk of hemorrhagic complications[7], several reports show a similar risk of major hemorrhagic complications after percutaneous renal biopsy[8,9]. Renal biopsy is important, and can be performed safely using the same screening criteria as for patients without MIg.

Our patient showed heavy chain amyloidosis, which is rare. One recent study suggested that, compared with light chain amyloidosis, heavy chain amyloidosis and heavy and light chain amyloidosis have less heart involvement and lower sensitivity of fat pad and bone marrow biopsy. The renal response to treatment is better, and the survival rate higher[10]. Our patient also showed a good response to treatment. Immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry staining of renal biopsy specimens can show the subtype of amyloidosis. However, 7.3% of cases of light chain amyloidosis fail to be diagnosed with immunostaining[11]. There can be false-negative results when epitopes are concealed or even deleted in the deposits[11,12]. On the other hand, the staining pattern can be nonspecific when several potential components have similar staining intensity simultaneously[13,14]. Serum protein contamination and charge interaction between antibody and deposit are possible reasons for this false-positive diagnoses. In our case, typing was difficult, since the patient had positive immunofluorescence staining for IgM, κ and λ at the same time. LMD/MS was performed, and finally confirmed μ chain (IgM) deposit. LMD/MS is suggested if there are negative or confusing immunostaining results.

IgA nephropathy in this patient was atypical. Peak incidence of IgA nephropathy is in the second and third decades of life, and it is rare for proteinuria to occur without microscopic hematuria. We suspected that IgA nephropathy might have been a mild indolent background in this patient, which happened to be discovered. Although no use of RASI for IgA nephropathy was a limitation of this case, treatment refractoriness to aggressive immunosuppressants still makes us question whether proteinuria was explained by conditions other than IgA nephropathy at the outset. Hetzel et al[15] reported a patient initially presenting with nephrotic syndrome and minimal change glomerulonephritis. However, repeated renal biopsy suggested light chain amyloidosis. Additionally, Thoenes et al[16] observed abundant pathologically-altered epithelia in amyloid-free loops in amyloidosis patients. They speculated that there must be patients with amyloidosis who do not yet show any amyloid in the glomeruli, but suffer from proteinuria. In our patient, we also suspected that proteinuria at the beginning may have been partly due to the “future” amyloidosis. Another explanation is that deposition of amyloid fibrils may be focal and easily missed at the early stage of amyloidosis. Therefore, the diagnosis of MGUS should be made carefully and be closely reassessed.

Patients with MGUS, especially the IgM type, may progress to different kinds of malignancy. Renal damage can also occur without hematological evidence of malignancy. Renal injury needs be monitored in those patients, especially in patients with pre-existing renal diseases. For some patients, proteinuria is suspected even before renal amyloidosis can be diagnosed. LMD/MS is useful in typing amyloidosis in difficult cases (Figure 3).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tovoli F S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Li X

| 1. | Anagnostopoulos A, Evangelopoulou A, Sotou D, Gika D, Mitsibounas D, Dimopoulos MA. Incidence and evolution of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) in Greece. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:357-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cabrera Q, Macro M, Hebert B, Cornet E, Collignon A, Troussard X. Epidemiology of Monoclonal Gammopathy of Undetermined Significance (MGUS): The experience from the specialized registry of hematologic malignancies of Basse-Normandie (France). Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38:354-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Leung N, Bridoux F, Hutchison CA, Nasr SH, Cockwell P, Fermand JP, Dispenzieri A, Song KW, Kyle RA; International Kidney and Monoclonal Gammopathy Research Group. Monoclonal gammopathy of renal significance: when MGUS is no longer undetermined or insignificant. Blood. 2012;120:4292-4295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, Offord JR, Larson DR, Plevak MF, Melton LJ. A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:564-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1081] [Cited by in RCA: 1010] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Paludo J, Ansell SM. Advances in the understanding of IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. F1000Res. 2017;6:2142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kyle RA, Benson J, Larson D, Therneau T, Dispenzieri A, Melton Iii LJ, Rajkumar SV. IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9:17-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Eiro M, Katoh T, Watanabe T. Risk factors for bleeding complications in percutaneous renal biopsy. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2005;9:40-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fish R, Pinney J, Jain P, Addison C, Jones C, Jayawardene S, Booth J, Howie AJ, Ghonemy T, Rajabali S, Roberts D, White L, Khan S, Morgan M, Cockwell P, Hutchison CA. The incidence of major hemorrhagic complications after renal biopsies in patients with monoclonal gammopathies. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1977-1980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Soares SM, Fervenza FC, Lager DJ, Gertz MA, Cosio FG, Leung N. Bleeding complications after transcutaneous kidney biopsy in patients with systemic amyloidosis: single-center experience in 101 patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:1079-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nasr SH, Said SM, Valeri AM, Sethi S, Fidler ME, Cornell LD, Gertz MA, Dispenzieri A, Buadi FK, Vrana JA, Theis JD, Dogan A, Leung N. The diagnosis and characteristics of renal heavy-chain and heavy/light-chain amyloidosis and their comparison with renal light-chain amyloidosis. Kidney Int. 2013;83:463-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Said SM, Sethi S, Valeri AM, Leung N, Cornell LD, Fidler ME, Herrera Hernandez L, Vrana JA, Theis JD, Quint PS, Dogan A, Nasr SH. Renal amyloidosis: origin and clinicopathologic correlations of 474 recent cases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1515-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Manabe S, Hatano M, Yazaki M, Nitta K, Nagata M. Renal AH Amyloidosis Associated With a Truncated Immunoglobulin Heavy Chain Undetectable by Immunostaining. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:1095-1100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kebbel A, Röcken C. Immunohistochemical classification of amyloid in surgical pathology revisited. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:673-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Satoskar AA, Burdge K, Cowden DJ, Nadasdy GM, Hebert LA, Nadasdy T. Typing of amyloidosis in renal biopsies: diagnostic pitfalls. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:917-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hetzel GR, Uhlig K, Mondry A, Helmchen U, Grabensee B. AL-amyloidosis of the kidney initially presenting as minimal change glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:630-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thoenes W, Schneider HM. Human glomerular amyloidosis -- with special regard to proteinuria and amyloidogenesis. Klin Wochenschr. 1980;58:667-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |