Published online Oct 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i19.3033

Peer-review started: June 3, 2019

First decision: August 1, 2019

Revised: August 22, 2019

Accepted: September 9, 2019

Article in press: September 9, 2019

Published online: October 6, 2019

Processing time: 125 Days and 3.4 Hours

Sweat glands belong to skin appendages. Sweat gland tumors are uncommon, especially when they occur as malignant tumors in the breast. We report a case of malignant sweat gland tumor of the breast, including imaging and pathological findings.

A 47-year-old woman visited our hospital with a non-tender palpable lesion in her left breast. The lesion had not shown changes for 10 years. However, it recently increased in size. Sonography showed a well circumscribed cystic lesion with internal debris and fluid-fluid level. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a well circumscribed oval mass with T1 hyper-intensity compared to muscle and T2 high signal intensity. There was a small enhancing mural component in the inner wall of the mass. The tumor was resected. Its pathologic result was a malignant transformation of benign sweat gland tumor such as hidradenoma. The lesion was treated with excision and radiation therapy. At 1-year follow up, there was no local recurrence or metastasis in the patient.

In the case of a rapid growing cystic mass in the nipple and subareola, it is necessary to distinguish it from a malignant sweat gland tumor.

Core tip: Sweat gland tumors of the breast are rare. They are clinically similar to benign cutaneous lesions. Imaging findings of sweat gland tumors have been rarely reported. This case will help us understand types of sweat gland tumors, the distinction between cutaneous and breast parenchymal lesions, and differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions.

- Citation: An JK, Woo JJ, Hong YO. Malignant sweat gland tumor of breast arising in pre-existing benign tumor: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(19): 3033-3038

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i19/3033.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i19.3033

The human body mainly consists of two types of sweat glands: Eccrine and apocrine sweat glands[1]. Eccrine glands are distributed in the palms, soles, axillae, and forehead while apocrine glands are mostly distributed in the axilla and anogenital area[2]. Apocrine glands can secrete a proteinaceous viscous sweat with a unique odor. The breast is sometimes regarded as a modified apocrine gland[3]. Eccrine sweat glands can secrete hypotonic sweat consisting mostly of water and electrolytes to control body temperature[1]. Sweat gland tumors are uncommon, especially when they occur in the breast. They have complex classification. These tumors have been reported under different names[4]. We report a case of malignant sweat gland tumor of the breast treated with excision and radiation therapy.

A 47-year-old female patient presented with a palpable lesion protruding from the left areola. This lesion was first noted 10 years earlier and had not shown changes. However, recently it noticeably increased in size.

She underwent breast augmentation surgery with silicone implants eight years ago.

Physical examination revealed a soft, fluctuating, mobile, and non-tender mass measuring approximately 4 cm in size. Part of the overlying skin was slightly greenish in appearance with mild protrusion. However, there was no ulcer or other skin changes.

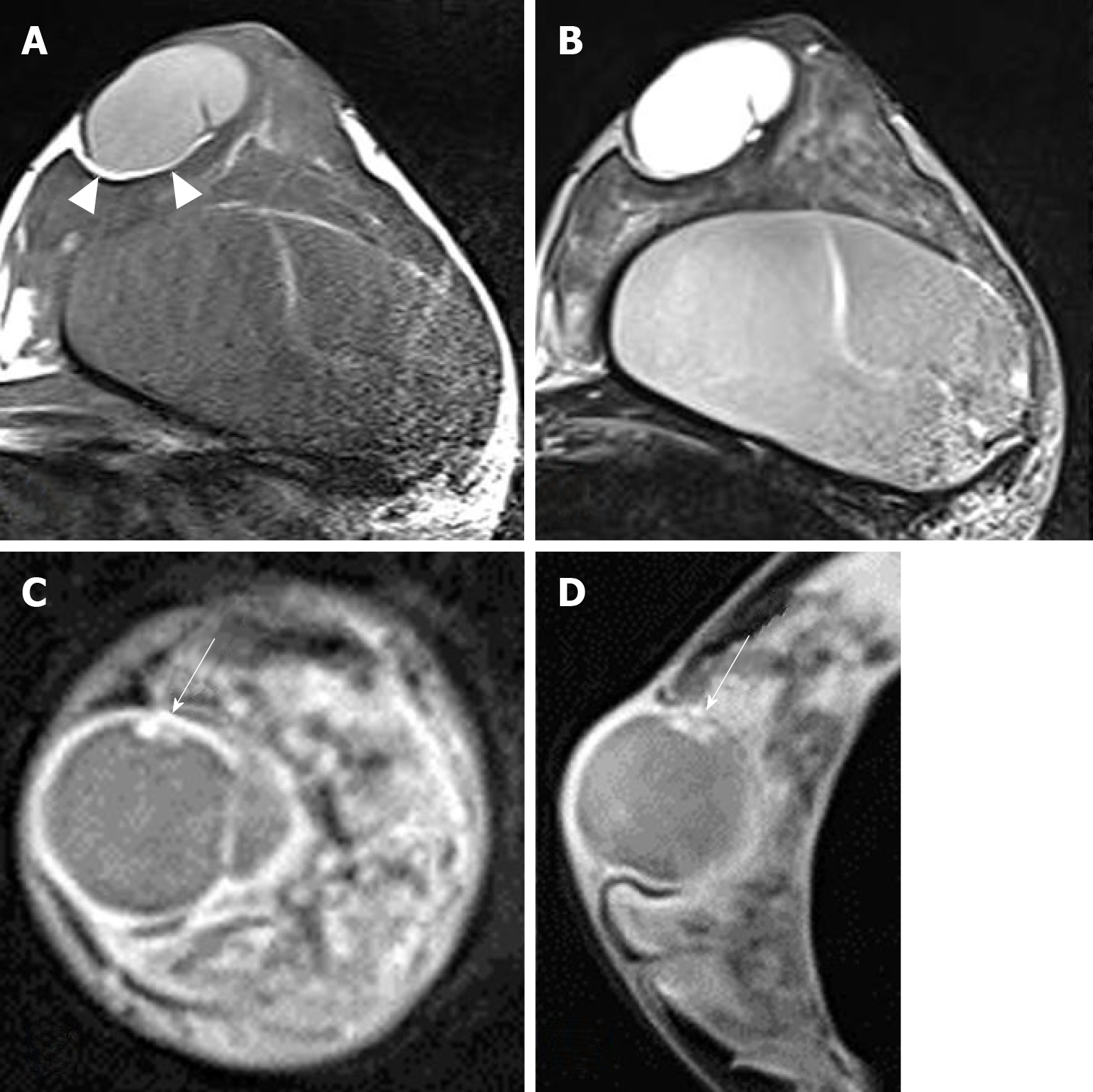

Sonography showed a well circumscribed oval cystic lesion with internal hyperechoic debris and fluid-fluid level. There was no internal blood flow on color doppler study. The mass broadly contacted with dermis, compressing the breast parenchyma (Figure 1). Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to check breast implants, on which the lesion could also be evaluated. MRI showed a well circumscribed oval mass of left subareolar area measuring 3.9 cm. The lesion attached to the cutaneous layer of the areola and compressed the breast parenchyma. Thin fatty layer was noted between the mass and the breast parenchyma, suggesting separated mass from the breast. The lesion showed T1 hyper-intensity compared to muscle and high T2 signal intensity. On post-contrast fat saturation T1-weighted image, the mass showed a well-circumscribed thin and even enhancing wall. There was a small enhancing mural component in the inner wall of the mass (Figure 2). It was not detected on ultrasound because internal debris filling the mass masked the mural component. In differentiation of the lesion, we overlooked the enhancing solid portion and considered the lesion as benign such as epidermal inclusion cyst.

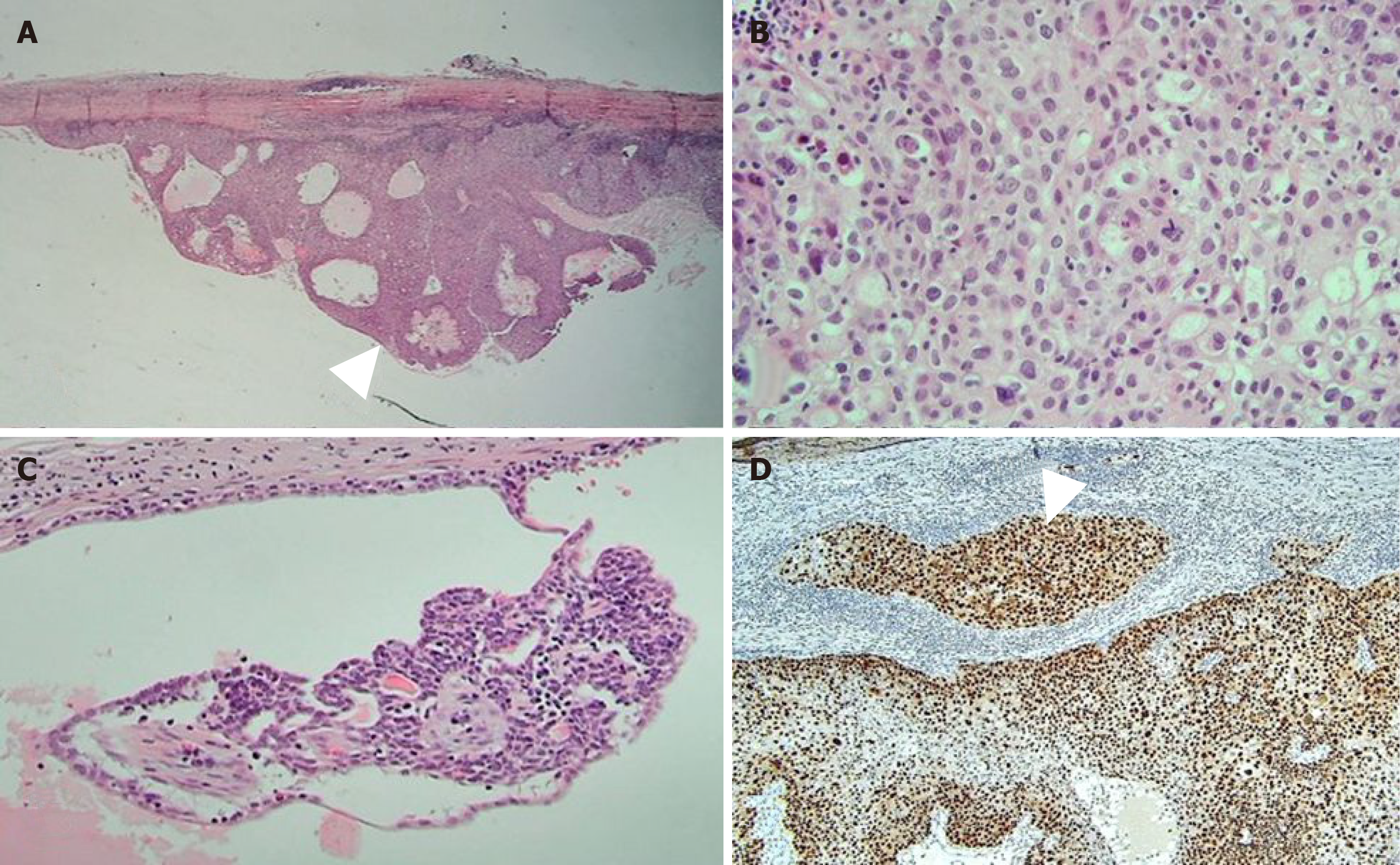

The tumor was resected due to its persistent and growing tendency. The mass was well demarcated with dense fibrous tissue. It was located between the breast parenchyma and the areola. The mass showed deep khaki color. It was filled with brownish and tan necrotic mucoid fluid. Microscopically, the lesion was predominantly cystic, measuring 3.5 cm × 2.5 cm × 2.4 cm with solid portion of 1 cm × 0.3 cm carcinoma and benign tissue of less than 0.1 cm. The carcinoma was composed of epithelial cells with clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm, prominent nucleoli, and frequent mitosis. Suspicious microinvasion to the fibrous cystic wall was noted (Figure 3). Resection margin was less than 1 mm and free of pathology. There was no lymphovascular invasion. Cytokeratin expression of the tumor showed positive for CK7 but negative for CK20. It was moderately positive for Ki-67, reflecting cell proliferation. Regarding other results in immunohistochemistry, it was positive for P63, C-erbB-2, and P53, but negative for estrogen and progesterone receptor.

Based on its history of a longstanding cutaneous mass, residual benign tissue, histology, and immunohistochemistry results of the carcinoma, the pathologic result was concluded to be malignant transformation of benign sweat gland tumor such as hidradenoma.

Depending on the pathological result of malignancy after resection, further surgery was considered. However, the lesion was well separated from the surrounding tissue at the time of operation and the specimen margin had no pathology. Moreover, additional lesions or pathological lymph nodes were not found on positron emission tomography-computed tomography (CT) performed after malignant diagnosis. Therefore, no further surgery was performed. Radiation therapy was performed at the site of excision.

The first follow-up was performed by ultrasound at six months after surgery. At 1-year follow up, she underwent mammogram, breast ultrasound, chest and abdominal CT, and bone scan. No local recurrence or metastasis was found in the patient.

Skin appendages are specialized skin structures located within the dermis and focally within the subcutaneous fatty tissue. They have three histologically distinct structures: The pilosebaceous unit, eccrine sweat glands, and apocrine glands. Tumors from skin appendages exhibit morphological differentiation toward one of thesis different types. Pilosebaceous units contain hair follicle and sebaceous glands. Eccrine and apocrine glands are origins of cutaneous sweat gland tumors. Skin adnexal lesions may display more than one line of differentiation. Thus, precise classification is difficult[5]. Furthermore, cutaneous sweat gland tumors are uncommon. Their classification is very complex with a wide histopathological spectrum and different terms to described the same neoplasm[4]. Thus, morphologic evaluation is very important for skin adnexal lesions. Special or immunohistochemical staining may occasionally serve as ancillary tool[5].

In the present case, features first considered for diagnosis were location, morphology, and cell elements. This lesion was located in the dermal and subcutaneous layer without epidermal connection. The tumor was cystic with focal solid component. Main cellular components were cells having clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm with frequent mitosis. A very small benign component remained within the mass. These findings strongly suggested malignant transformation of hidradenoma or hidradenocarcinoma[5,6].

Hidradenoma is a benign tumor that usually appears as a solitary skin-colored lesion. It can be larger than 2 cm in diameter. It can occur at any anatomical location and age[7,8]. It is classified as poroid hidradenoma of eccrine cell origin and clear cell hidradenoma of apocrine cell origin. Apocrine nodular hidradenoma is more frequent than eccrine variant. However, both subtypes could be present in the same lesion. It might be a solid and/or a solid-cystic mass in about 90% of cases[2,9].

Most cases of hidradenocarcinoma arise de novo. However, the tumor may also arise in pre-existing hidradenoma[10]. Hidradenocarcinoma has been reported in various names, including malignant nodular/clear cell hidradenoma, malignant clear cell acrospiroma, clear cell eccrine carcinoma, and primary mucoepidermoid cutaneous carcinoma. Tumor cells are similar to nodular hidradenoma. However, they can exhibit cytonuclear atypia with increased mitotic activity. There may be evidence of nodular hidradenoma remnants. Invasive growth patterns are not universally seen. Carcinomas can be distinguished from benign hidradenomas by the presence of active mitosis and cell polymorphism.

Immunohistochemistry results can support pathologic diagnosis. In our study, CK7 was positive. It was expressed in secretory coil of normal eccrine and apocrine glands. P63 is a marker of myoepithelial cells seen in most sweat gland tumors. It can be considered to differentiate the secretory coil of sweat glands. It is expressed in most of traditional apocrine tumors[7]. P63 is useful in a panel of antibodies for immunohistochemical differential diagnosis between sweat gland carcinoma other than primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma and skin metastasis of breast carcinoma[11]. Estrogen and progesterone receptors are often positive in skin tumors with eccrine differentiation[4]. However, they were not expressed in the present case. P53 is present in some sweat gland carcinomas. It is rarely present in benign tumors. Ki 67 reflects cell proliferation. Mitotic rate is an important indicator of malignancy[7]. It was moderately positive in the present case.

Imaging findings of hiradenoma or carcinoma have been rarely reported. Wortsman et al[12] have reported sonographic findings of cystic mass including solid portion, inner septa, internal moving echo mimicking snow falling, and fluid-fluid level with anechoic and hypoechoic fluid. Cho et al[13] have reported a sonographic finding of an oval, well circumscribed complex echoic mass in the subcutaneous layer. Another report has presented well-demarcated cystic masses with echolucent area and irregular mural nodules protruding from the cystic wall[14].

Maldjian et al[15] have described MRI findings of complex cystic mass with fluid levels of the cystic portion and enhancing solid component. The cystic portion demonstrated low to intermediate T1 intensity and high T2 signal intensity. Mullaney et al[16] have reported two MR findings of benign hidradenomas with complex cystic masses. The cystic component showed low to high T1 signal intensity and high T2 signal intensity while mural masses demonstrated low intensity T1 and T2 signals with no or homogeneous enhancement[16]. Different signal intensities of cystic components can result from relative differences in hemorrhage and sweat gland secretions.

The most common location of hidradenoma or hidradenocarcinoma in the breast has been reported to be the nipple and subareolar region[17-21]. There have been reports of circumscribed high-density masses on mammograms and cystic masses with significant solid components or mural nodule on sonogram[7,22,23].

Nodular hidradenoma should be completely removed as malignant transformation may occur in other parts of the lesion. In addition, hidradenoma has a recurrence rate of approximately 12% unless fully excised, especially for lesions with irregular peripheral margins[10]. Hidradenocarcinomas do not always behave aggressively. However, they can have aggressive course with metastasis and/or local recurrence. Primary treatment is extensive local resection with or without lymph node dissection[24,25].

Malignant sweat gland tumors of the breast are rare. They may appear similar to benign cystic masses. However, if the lesion develops in the nipple and subareolar area with rapid enlargement, it is necessary to distinguish it from malignant cystic lesion. Ultrasonography is useful as a primary modality while MRI is better for characterizing features of tumors with superior resolution. Pathologic confirmation is very important because the lesion may be similar to benign lesion in physical examination and/or imaging studies. Because treatment methods for malignant sweat gland tumors have not been fully established yet, complete excision with negative margin is important. Additional treatment such as radiation therapy could be considered.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ashkenazi I, Abulezz TA, Hosseini M, Kanat O, Avtanski D, Fiori E S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | Saga K. Structure and function of human sweat glands studied with histochemistry and cytochemistry. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2002;37:323-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kazakov DV, Michal M, Kacerovska D, Brown L. Skin Adnexal Tumors. Pathology of the Vulva and Vagina. Essentials of Diagnostic Gynecological Pathology. Brown L. London: Springer 2013; 245-271. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Weedon D, Strutton G, Rubin AI. 15-Diseases of cutaneous appendages. Weedon’s Skin Pathology (Third Edition). 2010;397-440. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Obaidat NA, Alsaad KO, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms--part 2: an approach to tumours of cutaneous sweat glands. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:145-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Alsaad KO, Obaidat NA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms--part 1: an approach to tumours of the pilosebaceous unit. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:129-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Alhumidi AA. Simple approach to histological diagnosis of common skin adnexal tumors. Pathol Lab Med Int. 2017;9:37-47. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Molina-Ruiz AM, Fuertes L, Requena L, Pla JA, Prieto VG. Immunohistology and Molecular Studies of Sweat Gland Tumors. Applied Immunohistochemistry in the Evaluation of Skin Neoplasms. Pla JA, Prieto VG. Cham: Springer 2016; 27-57. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Kakinuma H, Miyamoto R, Iwasawa U, Baba S, Suzuki H. Three subtypes of poroid neoplasia in a single lesion: eccrine poroma, hidroacanthoma simplex, and dermal duct tumor. Histologic, histochemical, and ultrastructural findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T. A study of histopathologic spectrum of nodular hidradenoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:461-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Crowson AN, Magro CM, Mihm MC. Malignant adnexal neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2006;19 Suppl 2:S93-S126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ansai SI. Topics in histopathology of sweat gland and sebaceous neoplasms. J Dermatol. 2017;44:315-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wortsman X, Reyes C, Ferreira-Wortsman C, Uribe A, Misad C, Gonzalez S. Sonographic Characteristics of Apocrine Nodular Hidradenoma of the Skin. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37:793-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cho KE, Son EJ, Kim JA, Youk JH, Kim EK, Kwak JY, Jeong J. Clear cell hidradenoma of the axilla: a case report with literature review. Korean J Radiol. 2010;11:490-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Horie K, Ito K. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of nodular hidradenoma. J Dermatol. 2016;43:449-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Maldjian C, Adam R, Bonakdarpour A, Robinson TM, Shienbaum AJ. MRI appearance of clear cell hidradenoma. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:104-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mullaney PJ, Becker E, Graham B, Ghazarian D, Riddell RH, Salonen DC. Benign hidradenoma: magnetic resonance and ultrasound features of two cases. Skeletal Radiol. 2007;36:1185-1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mote DG, Ramamurti T, Naveen Babu B. Nodular hidradenoma of the breast: A case report with literature review. Indian J Surg. 2009;71:43-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sehgal S, Goyal P, Ghosh S, Mittal D, Kumar A, Singh S. Clear cell hidradenoma of breast mimicking atypical breast lesion: a diagnostic pitfall in breast cytology. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:5343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Grampurohit VU, Dinesh U, Rao R. Nodular hidradenoma of male breast: Cytohistological correlation. J Cytol. 2011;28:235-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ohi Y, Umekita Y, Rai Y, Kukita T, Sagara Y, Sagara Y, Takahama T, Andou M, Sagara Y, Yoshida A, Yoshida H. Clear cell hidradenoma of the breast: a case report with review of the literature. Breast Cancer. 2007;14:307-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mezzabotta M, Declich P, Cardarelli M, Bellone S, Pacilli P, Riggio E, Pallino A. Clear cell hidradenocarcinoma of the breast: a very rare breast skin tumor. Tumori. 2012;98:43e-45e. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ghai S, Bukhanov K. Eccrine acrospiroma of breast: mammographic and ultrasound findings. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:1142-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chambers I, Rahal AK, Reddy PS, Kallail KJ. Malignant Clear Cell Hidradenoma of the Breast. Cureus. 2017;9:e1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Helwig EB. Eccrine acrospiroma. J Cutan Pathol. 1984;11:415-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Headington JT, Niederhuber JE, Beals TF. Malignant clear cell acrospiroma. Cancer. 1978;41:641-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |