Published online Sep 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i18.2843

Peer-review started: March 22, 2019

First decision: July 30, 2019

Revised: August 21, 2019

Accepted: August 25, 2019

Article in press: August 26, 2019

Published online: September 26, 2019

Processing time: 186 Days and 19.8 Hours

Aortic dissection during pregnancy is a rare but life-threatening event for mothers and fetuses. It often occurs in the third trimester of pregnancy and the postpartum period. Most patients have connective tissue diseases such as Marfan syndrome. Thus, the successful repair of a sporadic aortic dissection with maternal and fetal survival in the early second trimester is extremely rare.

A 28-year-old woman without Marfan syndrome presented with chest pain at the 16th gestational week. Aortic computed tomographic angiography confirmed an acute type A aortic dissection (TAAD) with aortic arch and descending aorta involvement. Preoperative fetal ultrasound confirmed that the fetus was stable in the uterus. The patient underwent total arch replacement with a frozen elephant trunk using moderate hypothermic circulatory arrest with the fetus in situ. The patient recovered uneventfully and continued to be pregnant after discharge. At the 38th gestational week, she delivered a healthy female infant by cesarean section. After 2.5 years of follow-up, the patient is uneventful and the child’s development is normal.

A fetus in the second trimester may have a high possibility of survival and healthy growth after aortic arch surgery.

Core tip: Aortic dissection during pregnancy is a rare but life-threatening event for mothers and fetuses. The successful repair of a sporadic aortic dissection with maternal and fetal survival in the early second trimester is exceedingly rare. This case highlights that a fetus in the second trimester may have a high possibility of survival and healthy growth after aortic arch surgery using hypothermic circulatory arrest.

- Citation: Chen SW, Zhong YL, Ge YP, Qiao ZY, Li CN, Zhu JM, Sun LZ. Successful repair of acute type A aortic dissection during pregnancy at 16th gestational week with maternal and fetal survival: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(18): 2843-2850

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i18/2843.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i18.2843

Type A aortic dissection (TAAD) is a disease with a high mortality rate that increases 1% to 2% per hour after the onset of symptoms in untreated patients. Moreover, acute aortic dissection during pregnancy is a rare and catastrophic disease that leads to extreme lethality of mothers and babies. The significant maternal and fetal mortality is as high as 30% and 50%, respectively[1]. Here, we present a case of TAAD who underwent moderate hypothermic circulatory arrest (MHCA) aortic surgery at the 16th gestational week.

A 28-year-old pregnant woman (G4P2) at the 16th gestational week was admitted to our emergency room, who complained of severe chest and back pain for 24 h.

The patient had severe, tearing chest pain that radiated to the back. The pain was continuous and could not be alleviated for 24 h. There were no adverse accompanying symptoms.

The patient had a history of miscarriage.

The patient had no family history.

The patient was 160 cm tall and weighed 58 kg (body mass index = 22.7). The patient’s temperature was 36.6 °C, heart rate was 78 bp/min, blood pressure was 130/70 mmHg, respiratory rate was 18 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation in room air was 98%. There were no murmurs from the cardiac auscultation. The pulses of both upper extremity arteries and dorsal arteries were equal. The bowel sounds were normal.

On admission, blood analysis revealed mild leukocytosis of 13 × 109/L with predominant neutrophils (94.9%). D-dimer and serum C-reactive protein levels increased to 8974 μg/mL and 35.5 mg/dL, respectively. In addition, hematocrit, platelet count, blood biochemistry, prothrombin, partial thromboplastin time as well as creatinine levels were normal.

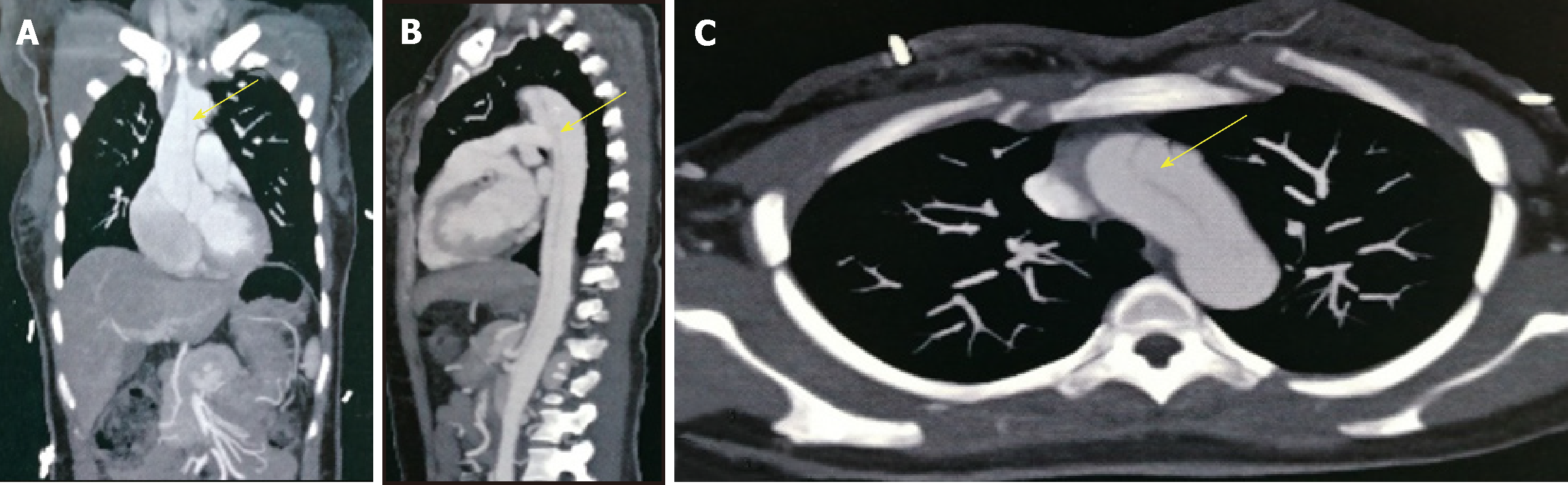

Aortic computed tomographic angiography (CTA) revealed an acute TAAD with the initial tear located at the ascending aorta (Figure 1). The aortic dissection involved the aortic arch and its branches and extended to the iliac arteries. The bloodstream of vital abdominal organs, including the celiac trunk, the mesenteric arteries, and the renal arteries, came from the true lumen. The diameter of the descending aorta was normal. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) showed mild regurgitation of the aortic valve without pericardial effusion. The inner diameters of the ascending aorta and the aortic sinuses were 37 mm and 31 mm, respectively. Fetal ultrasound confirmed that the fetus was stable without distress.

The patient was diagnosed with TAAD at the 16th gestational week. Fetal development was normal without intrauterine distress.

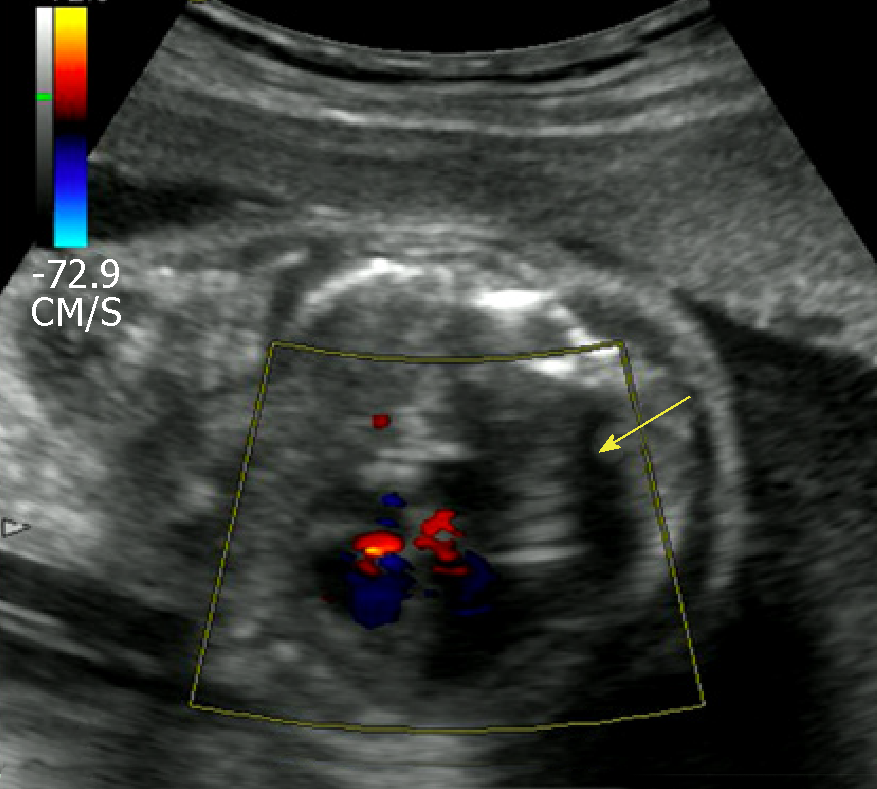

An emergency Sun’s procedure was performed with the fetus in situ. Our surgical technique was previously described in detail[2,3]. In brief, a median sternotomy was performed under MHCA with selective anterograde cerebral perfusion (SACP). The right axillary artery (RAA) cannulation was used for cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and SACP. The right femoral artery (RFA) cannulation was also utilized to increase the blood flow of the uterus. The distal ascending aorta was cross-clamped and the heart was arrested with perfusion of cold blood cardioplegia. The ascending aorta was replaced during the cooling phase. When the nasopharyngeal temperature reached 25 °C, the supra-arch vessels were cross-clamped and SACP was started (5-10 mL/kg/min). A stent elephant trunk (SET) (Cronus®, MicroPort Medical, Shanghai, China) was inserted into the true lumen of the descending aorta, and an anastomosis between the distal end of the four-branched prosthetic graft and the distal aorta incorporating the SET was performed. Therewith, the blood perfusion of the lower body was started via the limb of the prosthetic graft and RFA. Then, CPB was gradually resumed to normal flow and rewarming started. During the rewarming phase, the left common carotid artery, left subclavian artery, and innominate artery were reconstructed sequentially. The times of CPB, aortic cross-clamp, and SACP were 152 min, 66 min, and 17 min, respectively. During the surgery, the patient’s blood pressure was monitored via the radial artery and dorsal pedal artery. We also monitored the fetus using ultrasound and electronic fetal monitoring. No fetal distress was observed during the procedure (Figure 2).

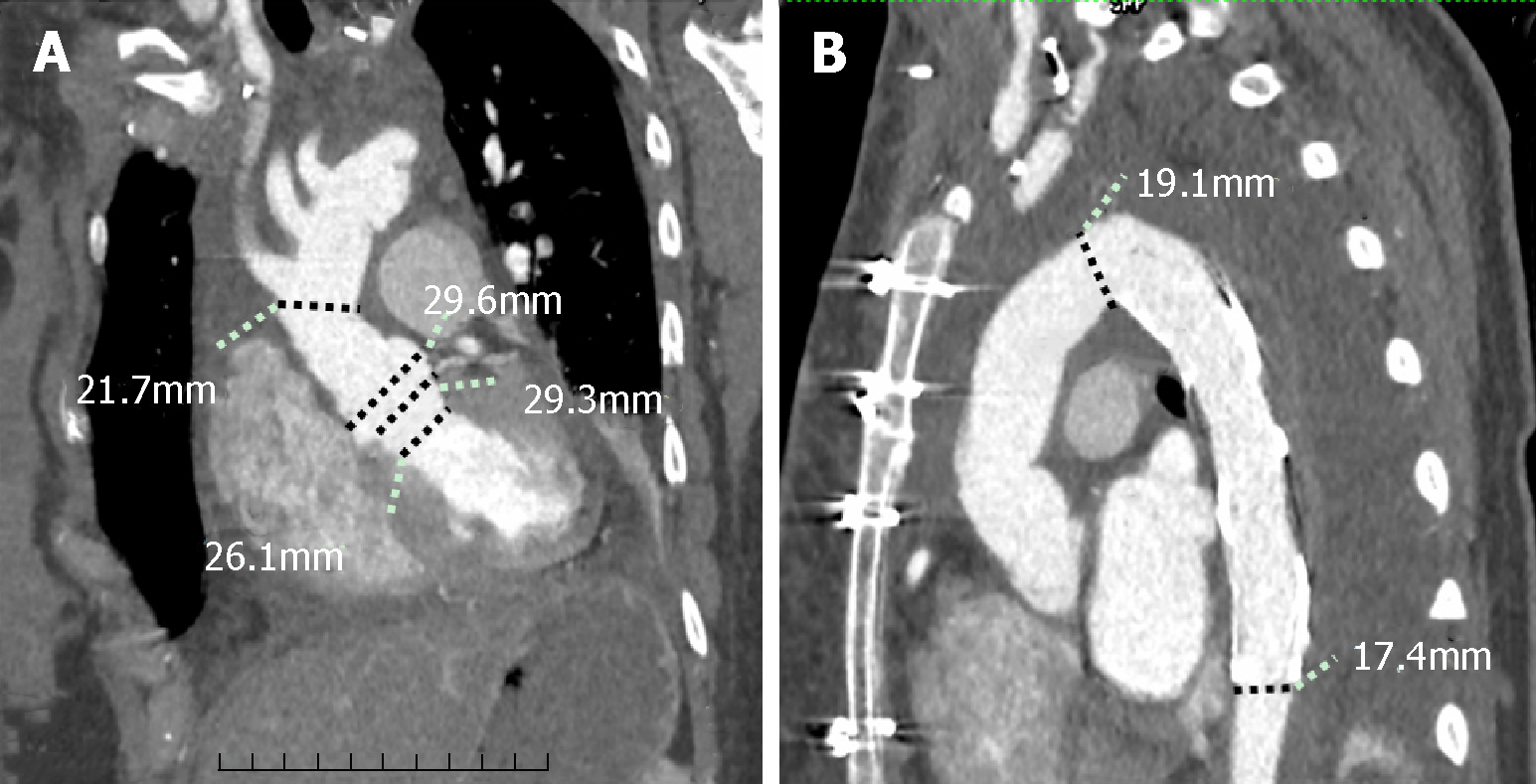

The times of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay were 12 h and 43 h, respectively. The patient received oral administration of Betaloc and Procardin to control heart rate and blood pressure after surgery. The postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged at 7 d postoperatively and continued the pregnancy. The aortic graft was patent and no anastomotic leakage was detected on discharge CTA (Figure 3). The patient underwent periodic prenatal examination and TTE between gestation week 16 and week 38. No obvious abnormality was found in the mother and the fetus. At the 38th gestational week, the patient delivered a healthy female infant by cesarean section. The Apgar score of the newborn was 10/10/10. The follow-up of the patient and newborn was satisfactory. The baby had no neurological or physiological abnormalities. Moreover, the patient and the baby did not receive any further intervention.

The most common phases for aortic dissection in pregnancy often occur in the third trimester and early postpartum period[4,5]. The incidence of aortic dissection in pregnant women is 7-fold higher than in non-pregnant people[6]. TAAD is usually associated with a high maternal risk and even higher fetal risk of death[7,8]. Thus, the correct options and management strategies are especially important for mothers and fetuses.

To meet the needs of fetal growth and development, the blood volume of pregnant women begins to increase at the 6th gestational week, peaks during the 32nd to 34th gestational weeks, and maintains at a high level until the postpartum period. Moreover, the signaling pathways also change during pregnancy[9]. Thus, pregnancy itself without any other complications is associated with a high risk of aortic dissection[10]. Moreover, a history of hypertension, aortitis, surgical manipulation, cardiac catheterization, cocaine exposure, and young age are also risk factors[1,9,11]. In the present case, the patient was at a young age but had no related history of illness. Therefore, the cause of aortic dissection may be related to young age and the pregnancy itself.

Although pregnant women should not be exposed to radiation, CTA can not only acquire sufficient information but can also be performed in a short period of time and can reconstruct the aorta in three dimensions, which may assist in surgical planning. The current guidelines suggested that low doses of radiation during CTA was acceptable in the diagnosis of aortic diseases in pregnancy[12]. Barrus et al[13] also suggested that CTA should be the primary diagnostic tool, and TTE should be a supplementary diagnostic method.

Immer-Bansi et al[14] reported a patient in which misinterpretation of the intraoperative cardiotocography led to an emergency caesarean section. Moreover, Barrus et al[13] reported a patient with aortic dissection who underwent repair surgery without effective monitoring for the fetus. Although the above studies consider medically futile of the intraoperative fetal monitoring, we believe that it can provide useful feedback for managing CPB and make a comprehensive assessment of the fetus during and after surgery.

CPB induces a systemic inflammatory response[15] that increases the risk of maternal and fetal deaths, which are approximately 3% and 20%, respectively[16,17]. The literature considered that the processes of cooling and rewarming both decreased blood flow to the uterus and placenta and increased contractions that prompt fetal bradycardia and intrauterine hypoxia[11,16,18]. The blood flow to the uterus cannot adjust by itself and mainly relies on mean arterial pressure and vascular resistance. Moreover, the hypothermic circulatory arrest (HCA) may also lead to fetal brain atrophy and death[19,20]. However, HCA is still inevitable for TAAD involving the aortic arch. In this case, in order to reduce the risk of adverse events, we used moderate hypothermia and maintained a high flow rate (> 2.4 L/m2/min) with mean arterial pressure > 70 mm during CPB. For myocardial protection, we chose cold blood cardioplegia rather than cold crystal cardioplegia[21]. Meanwhile, both RAA and RFA cannulations were used to maintain a stable and approximate physiological blood flow to the upper and lower body. In addition, SACP not only provided effective cerebral protection for mothers but also had no influence on placental perfusion[11].

The timing of aortic surgery should be based on the types of dissection, the conditions of the fetus, and gestational age[21]. Currently, although different experts had different perspectives on specific gestational weeks to perform aortic surgery and cesarean section, many studies suggested that the optimal timing for cesarean section followed by aortic repair was after reaching fetal maturity[1,22-24], in which the fetal organogenesis was basically complete, and the fetus could survive outside the womb. The probability of independent fetal survival was low before 23 gestational weeks[11]. Therefore, when aortic dissection occurs before fetal maturity, an urgent aortic repair with aggressive fetal monitoring is preferred. However, the risk of fetal developmental anomalies during the first trimester is significantly increased after aortic arch surgery. The probability of fetal survival and normal growth may not be high. Thus, the main controversy is whether fetuses in the second trimester can survive aortic surgery using HCA and eventually have full-term delivery healthily.

According to the gestational age and HCA surgery, we summarize the cases with TAAD who underwent aortic arch surgery in the literature[7,13,17,19,25-33] (Table 1). In these 13 patients, all mothers survived. Only one fetus died and one fetus had neurological abnormalities. Moreover, half of the patients were in the second trimester. In spite of fetal death and postnatal neurological abnormalities, the results showed that most fetuses survived and brought up healthily. Thus, if the immature fetuses can survive after HCA surgery in the second trimester, they may have a high possibility of full-term delivery and healthy growth.

| No. | Author | Age (Yr) | GWs | HCA (°C) | HCA (min) | CPB (min) | MBFR | MPP | SCP | Fetus | Mother |

| 1 | Buffolo et al[25] | 28 | 21 | 19 | 37 | 120 | 2.4 | 60 | — | S/N | Alive |

| 2 | Shaker et al[29] | 34 | 35 | 18 | 11 | — | — | — | ACP | S/N | Alive |

| 3 | Sakaguchi et al[17] | 33 | 26 | 20 | 80 | 367 | — | — | — | Died | Alive |

| 4 | Ham et al[27] | 43 | 37 | 11 | 37 | — | — | — | ACP | S/N | Alive |

| 5 | Barrus et al[13] | 31 | 21 | 18 | 25 | 228 | >4.5 | 70 | RCP | S/N | Alive |

| 6 | Seeburger et al[26] | 27 | 17 | 22 | 20 | 244 | — | — | — | S/N | Alive |

| 7 | Marumoto et al[28] | 28 | 33 | 23 | 37 | 137 | — | — | — | S/N | Alive |

| 8 | Kunishige et al[7] | 32 | 16 | 22.8 | 46 | 302 | > . 4.5 | 80 | — | S/N | Alive |

| 9 | Easo et al[30] | 28 | 24 | 28 | 21 | — | — | — | ACP | S/N | Alive |

| 10 | Dong et al[31] | 27 | 29 | 24.6 | 21 | 198 | — | — | — | S/N | Alive |

| 11 | Nonga et al[32] | 29 | 29 | — | 56 | 253 | — | — | — | S/N | Alive |

| 12 | Shihata et al[33] | 36 | 35 | — | — | 260 | — | — | ACP | S/N | Alive |

| 13 | Mul et al[19] | 32 | 29 | 28 | 5 | — | >5.5 | >70 | — | S/A | Alive |

In addition to surgery, some drugs can also affect the outcomes. Vasoconstrictors should be avoided for pregnant patients during the perioperative period[29], because it will increase contractions, resulting in fetal hypoxia. Although beta-blockers are thought to reduce aortic dilatation and aortic growth[34], the evidence is still insufficient and controversial[35]. The common side effects are fetal bradycardia and growth restriction[36]. Besides, Warfarin is considered teratogenic as well[1]. In the present case, the aortic valve was preserved, thus the effects of Warfarin were avoided. In addition, although the patient was treated with a beta-blocker and calcium channel blocker, fetal development was not affected. Generally, the fetuses should be closely monitored to avoid adverse outcomes if mothers are treated with the above drugs.

Postpartum hemorrhage is an important cause of maternal death. To prevent uterine bleeding, Yang et al suggested that a hysterectomy should be actively performed after cesarean section[37]. However, in our present case, the insertion of a Cook balloon was safe and effective in reducing secondary damage[21].

If fetuses can survive after HCA surgery in the second trimester, they may have a high possibility of full-term delivery and healthy growth.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yellanthoor RB, Ajmal M, Altarabsheh SE S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Zhou BX

| 1. | Immer FF, Bansi AG, Immer-Bansi AS, McDougall J, Zehr KJ, Schaff HV, Carrel TP. Aortic dissection in pregnancy: analysis of risk factors and outcome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:309-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ma WG, Zhu JM, Zheng J, Liu YM, Ziganshin BA, Elefteriades JA, Sun LZ. Sun's procedure for complex aortic arch repair: total arch replacement using a tetrafurcate graft with stented elephant trunk implantation. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;2:642-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sun L, Qi R, Zhu J, Liu Y, Zheng J. Total arch replacement combined with stented elephant trunk implantation: a new "standard" therapy for type a dissection involving repair of the aortic arch? Circulation. 2011;123:971-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Loeys BL, Dietz HC, Braverman AC, Callewaert BL, De Backer J, Devereux RB, Hilhorst-Hofstee Y, Jondeau G, Faivre L, Milewicz DM, Pyeritz RE, Sponseller PD, Wordsworth P, De Paepe AM. The revised Ghent nosology for the Marfan syndrome. J Med Genet. 2010;47:476-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1234] [Cited by in RCA: 1367] [Article Influence: 91.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Crawford JD, Hsieh CM, Schenning RC, Slater MS, Landry GJ, Moneta GL, Mitchell EL. Genetics, Pregnancy, and Aortic Degeneration. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;30:158.e5-158.e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Howard DP, Banerjee A, Fairhead JF, Perkins J, Silver LE, Rothwell PM; Oxford Vascular Study. Population-based study of incidence and outcome of acute aortic dissection and premorbid risk factor control: 10-year results from the Oxford Vascular Study. Circulation. 2013;127:2031-2037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 388] [Cited by in RCA: 588] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kunishige H, Ishibashi Y, Kawasaki M, Yamakawa T, Morimoto K, Inoue N. Surgical treatment for acute type A aortic dissection during pregnancy (16 weeks) with Loeys-Dietz syndrome. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;60:764-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jovic TH, Aboelmagd T, Ramalingham G, Jones N, Nashef SA. Type A Aortic Dissection in Pregnancy: Two Operations Yielding Five Healthy Patients. Aorta (Stamford). 2014;2:113-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Smok DA. Aortopathy in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 2014;38:295-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sawlani N, Shroff A, Vidovich MI. Aortic dissection and mortality associated with pregnancy in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1600-1601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lansman SL, Goldberg JB, Kai M, Tang GH, Malekan R, Spielvogel D. Aortic surgery in pregnancy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:S44-S48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, Bossone E, Bartolomeo RD, Eggebrecht H, Evangelista A, Falk V, Frank H, Gaemperli O, Grabenwöger M, Haverich A, Iung B, Manolis AJ, Meijboom F, Nienaber CA, Roffi M, Rousseau H, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Allmen RS, Vrints CJ; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: Document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2873-2926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2374] [Cited by in RCA: 3099] [Article Influence: 281.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Barrus A, Afshar S, Sani S, LaBounty TG, Padilla C, Farber MK, Rudikoff AG, Hernandez Conte A. Acute Type A Aortic Dissection and Successful Surgical Repair in a Woman at 21 Weeks Gestational Pregnancy With Maternal and Fetal Survival: A Case Report. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32:1487-1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Immer-Bansi A, Immer FF, Henle S, Spörri S, Petersen-Felix S. Unnecessary emergency caesarean section due to silent CTG during anaesthesia? Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:791-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Taylor KM. SIRS--the systemic inflammatory response syndrome after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:1607-1608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pomini F, Mercogliano D, Cavalletti C, Caruso A, Pomini P. Cardiopulmonary bypass in pregnancy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:259-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sakaguchi M, Kitahara H, Seto T, Furusawa T, Fukui D, Yanagiya N, Nishimura K, Amano J. Surgery for acute type A aortic dissection in pregnant patients with Marfan syndrome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28:280-3; discussion 283-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Becker RM. Intracardiac surgery in pregnant women. Ann Thorac Surg. 1983;36:453-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mul TF, van Herwerden LA, Cohen-Overbeek TE, Catsman-Berrevoets CE, Lotgering FK. Hypoxic-ischemic fetal insult resulting from maternal aortic root replacement, with normal fetal heart rate at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:825-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rajagopalan S, Nwazota N, Chandrasekhar S. Outcomes in pregnant women with acute aortic dissections: a review of the literature from 2003 to 2013. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2014;23:348-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhu JM, Ma WG, Peterss S, Wang LF, Qiao ZY, Ziganshin BA, Zheng J, Liu YM, Elefteriades JA, Sun LZ. Aortic Dissection in Pregnancy: Management Strategy and Outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:1199-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wanga S, Silversides C, Dore A, de Waard V, Mulder B. Pregnancy and Thoracic Aortic Disease: Managing the Risks. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32:78-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kohli E, Jwayyed S, Giorgio G, Bhalla MC. Acute type a aortic dissection in a 36-week pregnant patient. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2013;2013:390670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sato S, Ogino H, Matsuda H, Sasaki H, Tanaka H, Iba Y. Annuloaortic ectasia treated successfully in a pregnant woman with Marfan syndrome: report of a case. Surg Today. 2012;42:285-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Buffolo E, Palma JH, Gomes WJ, Vega H, Born D, Moron AF, Carvalho AC. Successful use of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest in pregnancy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:1532-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Seeburger J, Mohr FW, Falk V. Acute type A dissection at 17 weeks of gestation in a Marfan patient. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:674-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ham S. Emergency repair of aortic dissection in a 37-week parturient: a case report. AANA J. 2010;78:63-68. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Marumoto A, Nakamura Y, Harada S, Saiki M, Nishimura M. Acute aortic dissection at 33 weeks of gestation with fetal distress syndrome. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;59:566-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Shaker WH, Refaat AA, Hakamei MA, Ibrahim MF. Acute type A aortic dissection at seven weeks of gestation in a Marfan patient: case report. J Card Surg. 2008;23:569-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Easo J, Horst M, Schmuck B, Thomas RP, Saupe S, Book M, Weymann A. Retrograde type a dissection in a 24th gestational week pregnant patient - the importance of interdisciplinary interaction to a successful outcome. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;13:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Dong X, Lu J, Cheng W, Wang C. An atypical presentation of chronic Stanford type A aortic dissection during pregnancy. J Clin Anesth. 2016;33:337-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Nonga BN, Pasquet A, Noirhomme P, El-Khoury G. Successful bovine arch replacement for a type A acute aortic dissection in a pregnant woman with severe haemodynamic compromise. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15:309-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Shihata M, Pretorius V, MacArthur R. Repair of an acute type A aortic dissection combined with an emergency cesarean section in a pregnant woman. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2008;7:938-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Meijboom LJ, Vos FE, Timmermans J, Boers GH, Zwinderman AH, Mulder BJ. Pregnancy and aortic root growth in the Marfan syndrome: a prospective study. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:914-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Gersony DR, McClaughlin MA, Jin Z, Gersony WM. The effect of beta-blocker therapy on clinical outcome in patients with Marfan's syndrome: a meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2007;114:303-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lydakis C, Lip GY, Beevers M, Beevers DG. Atenolol and fetal growth in pregnancies complicated by hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12:541-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yang Z, Yang S, Wang F, Wang C. Acute aortic dissection in pregnant women. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;64:283-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |