Published online Sep 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i18.2831

Peer-review started: March 18, 2019

First decision: August 1, 2019

Revised: August 13, 2019

Accepted: August 25, 2019

Article in press: August 26, 2019

Published online: September 26, 2019

Processing time: 192 Days and 20.1 Hours

Status epilepticus is an emergent and critical condition which needs management without hesitation. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) tends to be less recognized, and its diagnosis is delayed in comparison with overt status epilepticus because of the absence of specific clinical signs. It is often difficult to make a diagnosis, particularly in patients with hepatic encephalopathy.

A 38-year-old man with a history of alcoholic liver cirrhosis presented with altered mental status; the initial diagnosis was hepatic encephalopathy. Although optimal treatment for hepatic encephalopathy was administered, the patient's mental status did not improve. A final diagnosis of NCSE was made by continuous electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring. Treatment with levetiracetam and propofol pump was immediately started. The patient’s consciousness gradually improved after discontinuation of propofol therapy, and no further epileptic discharge was observed by EEG monitoring. After 1 wk, the patient returned to full consciousness, and he was able to walk in the hospital ward without assistance. He was discharged with minimal sequela of bilateral conjunctivitis.

In cases of persistent altered mental status without reasonable diagnosis, NCSE should be considered in hepatic encephalopathy patients with persistently altered levels of consciousness, and EEG monitoring is very important. We also recommend propofol as a safe and efficient therapy for NCSE in liver cirrhosis patients.

Core tip: This case highlights the probability of nonconvulsive status epilepticus in patients with liver cirrhosis who do not respond to standard treatment. A multidisciplinary team that includes a neurologist, intensivists, and electroencephalography technicians would contribute to achieving a general improvement in patients with this condition. We also recommend that propofol is a reasonable choice of treatment in such cases.

- Citation: Hor S, Chen CY, Tsai ST. Propofol pump controls nonconvulsive status epilepticus in a hepatic encephalopathy patient: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(18): 2831-2837

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i18/2831.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i18.2831

In the eight-year case series of France[1], the Brain-Liver team estimated a prevalence of 0.7% for status epilepticus (SE) in patients with cirrhosis [15 of 2010 patients admitted to intensive care unit (ICU)]. And less than three cases (0.15%) could be considered to be non-convulsive SE (NCSE). Although the low incidence, its in-hospital mortality was high (73%). NCSE may not be easily recognized because of the lack of obvious convulsions in comparison with NCSE, and treatment may thus be delayed. It is often difficult to diagnose, particularly in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Choosing the most appropriate antiepileptic drug in this setting is also challenging because most medications are metabolized by the liver. For example, benzodiazepines are predominantly metabolized in the liver. Valproic acid is mainly eliminated through the liver, and in patients with hepatic diseases, its metabolism could potentially shift to alternative pathways with the production of hepatotoxic metabolites[2]. Here we report the case of a patient in whom hepatic encephalopathy was strongly suspected and whose ultimate diagnosis was NCSE, which was controlled with a propofol pump. Based on our literature review, this is the first reported case in Taiwan.

A 38-year-old man arrived at our emergency department with acutely altered mental status.

The patient suffered from alcoholism and had a known history of recurrent episodes of hepatic encephalopathy; the most recent episode had happened 5 mo earlier. He had stopped drinking alcohol for 5 mo and had started drinking again 1 wk prior to this presentation. On the morning of admission, the family had incidentally found him lying in bed, confused and lethargic, and immediately called an ambulance.

The patient did not have any history of disease and did not have a history of seizures or brain trauma, and he had not recently undergone surgery.

The patient has been drinking alcohol everyday for 16 years. Family history was not contributory.

Upon arrival, the patient had a blood pressure of 96/56 mm Hg, pulse rate of 132 beats per minute, body temperature of 37.5 °C, respiratory rate of 22 breaths per min, and oxygen saturation of 96% in room air. Physical examination revealed no acute distress and a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 5 (eyes, 1; verbal, 3; and motor, 1). No signs of trauma were observed on his body. His pupils were equal in size, round, and nonreactive to light. Cardiopulmonary and abdominal examination findings were unremarkable. Bilateral Babinski signs were absent, but the neurological examination otherwise was limited because the patient could not follow commands.

Laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 9900/μL with 75.8% of neutrophils, hemoglobin level of 17.6 g/dL, hematocrit of 50.6%, and platelet count of 117000/μL. Electrolyte, liver function, and blood chemistry results were as follows: Sodium, 132 mmol/L; potassium, 3.5 mmol/L; calcium, 8.2 mg/dL; magnesium, 2.4 mg/dL; blood urea nitrogen, 34 mg/dL; creatinine, 2.72 mg/dL; total bilirubin, 6.7 mg/dL; direct bilirubin, 3.8 mg/dL; alanine aminotransferase, 496 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase, 163 IU/L; albumin, 3.9 g/dL; lipase, 73 IU/L; prothrombin time (international normalized ratio), 1.17; and ammonia, 277.7 μmol/L (reference range, 6-47 μmol/L). The fasting blood glucose level was 168 mg/dL; the lactate level was 71.5 mg/dL. The arterial blood gas pH was 7.29 (partial pressure of carbon dioxide, 56 mm Hg; partial pressure of oxygen, 71 mm Hg; and actual bicarbonate level, 26.9 mmol/L).

Electrocardiograms and chest radiographs revealed no acute pathological finding. Brain computed tomography without contrast enhancement revealed no hemorrhage or acute ischemic stroke. Abdominal computed tomography showed atelectasis in both lower lung zones, fatty liver, and ileus.

In the emergency department, one episode of generalized seizure with frothing at the mouth and both eyes deviated to the left side lasting for several minutes was noted. An intravenous injection of lorazepam (1 ampoule of 2 mg) was immediately administered for seizure control; at that time, the patient’s Glasgow Coma Scale score was 3 (eyes, 1; verbal, 1; and motor, 1). The patient was intubated and admitted to an ICU for monitoring with a diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy. Lorazepam and vitamin B infusion were administered to prevent alcohol withdrawal syndrome; lactulose (30 mL) via a nasogastric tube was administered three times per day for management of hepatic encephalopathy, and broad-spectrum empirical antibiotics were administered for control of any infection. On the second day of his hospitalization, several episodes of involuntary bilateral feet dorsiflexion were noted. His ammonia level decreased to 88.1 μmol/L by the third day of hospitalization, but intermittent involuntary movement in the lower face was still noted.

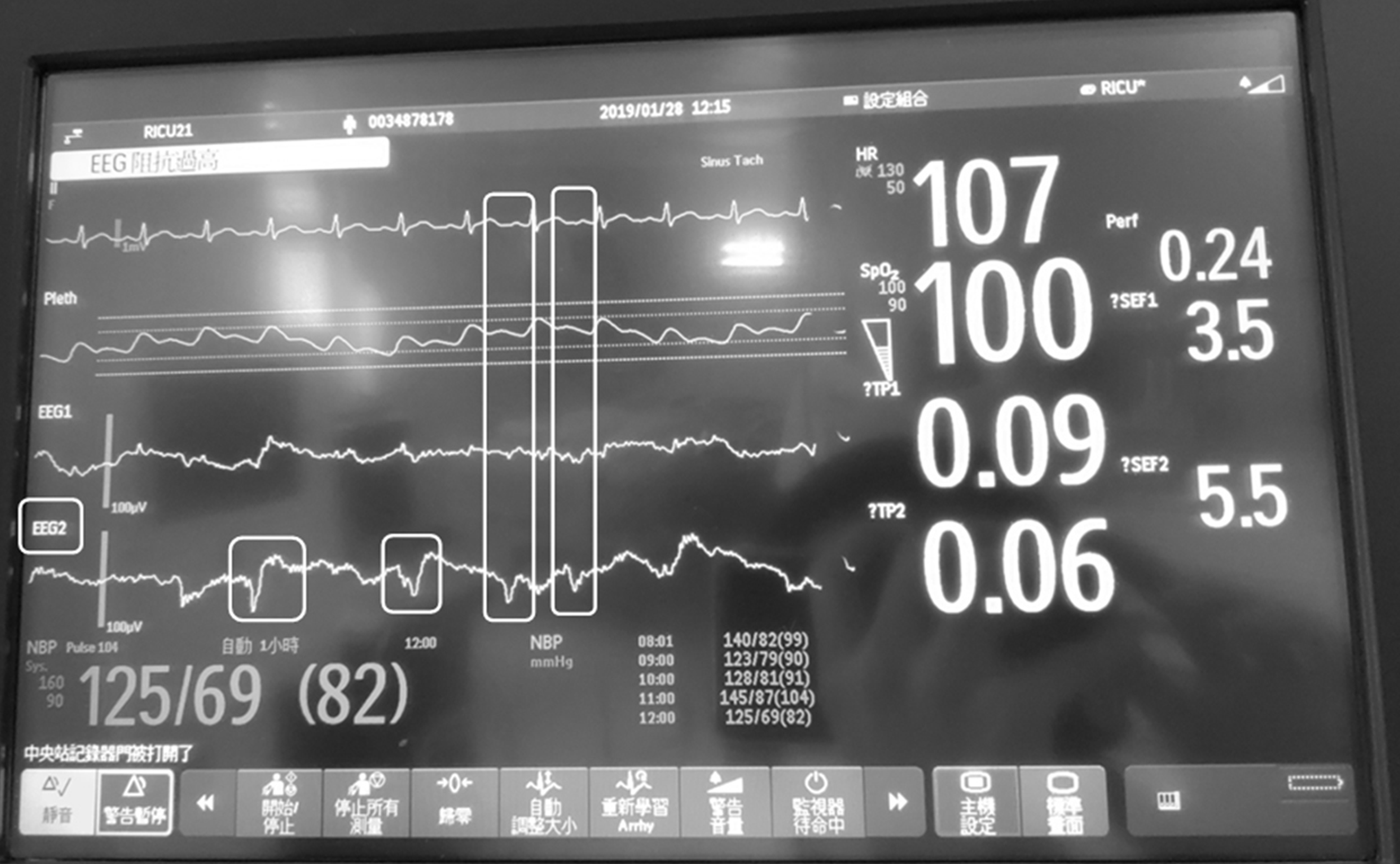

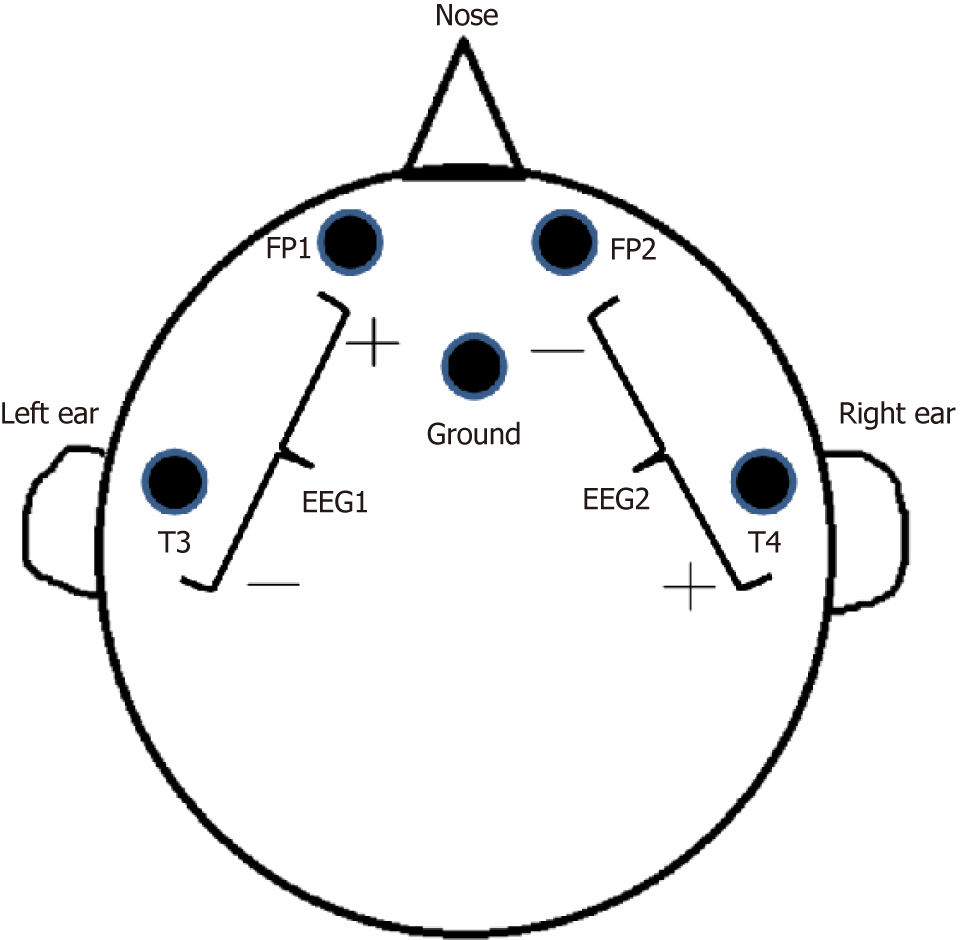

A neurologist was consulted; a bedside electroencephalogram (EEG) was performed, which revealed intermittent spike-and-wave patterns, predominantly in the right hemisphere (Figures 1 and 2).

Nonconvulsive SE.

We intravenously administered levetiracetam (1 vial) every 12 h and initiated propofol pump infusion. We adjusted the dosage of propofol based on continuous EEG monitoring. The formal EEG (International 10-20 system) was obtained one day later, while the patient was under propofol sedation. It did not show epileptic discharge. We started to taper down the dose of propofol after 40 h of infusion, and no more spike-and-wave pattern was noted on the bedside EEG monitor.

The patient became alert and oriented, and he achieved a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15 (eyes, 4; verbal, 5; and motor, 6) on the 12th day of hospitalization. The endotracheal tube was successfully removed. The patient was subsequently transferred to an ordinary hospital ward, and he demonstrated that he could walk around without assistance. On the 18th day of hospitalization, the patient was discharged and continued to do well on subsequent follow-up monitoring.

First of all, the most important is the diagnosis of NCSE. According to the 2015 Salzburg Electroencephalography Consensus Criteria for NCSE[3] (Table 1), our patient had epileptiform discharge (ED) ≤ 2.5/s (around 0.58 Hz, Figure 1). So we need to find additional criteria to make the diagnosis. Our patient got some involuntary movements (bilateral feet subtle dorsiflexion) during the ICU. It fulfilled the subtle clinical ictal phenomena. But according to the previous study published by Rudler et al[1], some abnormal movements are non-epileptic, which are easy to be misdiagnosed as SE. Therefore, we checked the continuous EEG monitor during the patient’s feet movements. The EEG monitor showed spike and wave complex at that time, instead of triphasic wave (characteristic of hepatic encephalopathy). Also the EEG of the patient had no reactivity to external stimulus (favoring epileptiform discharge). Because of the above reasons, we diagnosed this case as NCSE according to the EEG monitoring (we cannot perform the 10-20 EEG at that time because of the limitation of facility). And the clinical improvement by propofol pump supported our diagnosis. In addition, some specific findings in diffusion-weighted imaging sequences of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (cortical or subcortical hyperintensity) may also support the diagnosis of SE[4]. In our case, the consciousness of the patient recovered to his usual status without sequela. We did not perform brain MRI for him. We consider to arrange the MRI examination a few months later for follow-up.

| 2015 Salzburg Electroencephalography Consensus Criteria |

| Epileptiform discharge > 2.5/s |

| Or |

| Epileptiform discharge ≤ 2.5/s and at least one of the additional criteria: |

| 1 Clinical and EEG improvements from antiepileptic drugs |

| 2 Subtle clinical ictal phenomena |

| 3 Typical spatiotemporal evolution |

We found three similar case reports (Table 2) in the literature. In these case reports, patients with underlying hepatic diseases presented with symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy, but NCSE was later confirmed by EEG[5-7]. As in our case, the mental status of those patients did not improve despite optimal medical treatment and a decrease in ammonia level. In each case, after the multidisciplinary team discussed patient’s clinical conditions, the neurologist made a final diagnosis of NCSE by bedside continuous EEG monitoring; treatment was immediately started. These cases told us that in cases of unexplained alteration in mental status like our situation, NCSE should be considered, and EEG should be immediately obtained[8,9].

| Age | Liver disease | Glasgow Coma Scale | Initial ammonia | Treatment | Country | Journal/Published year |

| 64 | HCV infection status post liver transplant | E4V3M5 | 501 µmol/L | Phenytoin, midazolam | United States | Western Journal of Emergency Medicine/2011 |

| 45 | HCV related cirrhosis, HIV infection on HAART | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Pakistan | Journal of Medical Case Reports/2012 |

| 52 | HBV related cirrhosis, HCC | E3V4M4 → E4V5M6 after lactulose and rifaximin (ammonia: 63) → E1V1M2 (ammonia: 112) | 88 µmol/L | Unknown | Korea | World Journal of Gastroenterology/2015 |

| 38 | Alcoholic cirrhosis | E1V3M1 (ammonia: 88.1 µmol/L) → E4V5M6 (ammonia: 48.7 µmol/L) | 277.7 μmol/L → 88.1 µmol/L | Levetiracetam, propofol pump | Taiwan | World Journal of Clinical Cases/2019 |

About the treatment, we chose propofol because of its safety in patients with hepatic failure[10,11]. However, we were concerned about propofol infusion syndrome, which is characterized by cardiac failure, rhabdomyolysis, severe metabolic acidosis, and renal failure, and may occur if duration of treatment is longer than 48 h[12]. We discontinued the propofol infusion after 40 h to prevent this syndrome. We also regularly checked our patient’s venous gas, creatine kinase, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine values.

Our patient benefited from early multidisciplinary team intervention and immediate EEG monitoring. In a referral center, a multidisciplinary team that includes a neurologist, intensivists, and electroencephalography technicians would contribute to achieve a general improvement in patients with this condition.

In an evaluation of patients with liver cirrhosis who present with change of consciousness, it is important to consider the possibility of NCSE, particularly in patients who do not respond to standard treatment. And the EEG is the examination of choice to get the prompt diagnosis of SE. We also believe that propofol is a reasonable choice of treatment in such cases.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Loustaud-Ratti V S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Rudler M, Marois C, Weiss N, Thabut D, Navarro V; Brain-Liver Pitié-Salpêtrière Study Group (BLIPS). Status epilepticus in patients with cirrhosis: How to avoid misdiagnosis in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Seizure. 2017;45:192-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Vidaurre J, Gedela S, Yarosz S. Antiepileptic Drugs and Liver Disease. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;77:23-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Leitinger M, Beniczky S, Rohracher A, Gardella E, Kalss G, Qerama E, Höfler J, Hess Lindberg-Larsen A, Kuchukhidze G, Dobesberger J, Langthaler PB, Trinka E. Salzburg Consensus Criteria for Non-Convulsive Status Epilepticus--approach to clinical application. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;49:158-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Newey CR, George P, Sarwal A, So N, Hantus S. Electro-Radiological Observations of Grade III/IV Hepatic Encephalopathy Patients with Seizures. Neurocrit Care. 2018;28:97-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Badshah MB, Riaz H, Aslam S, Badshah MB, Korsten MA, Munir MB. Complex partial non-convulsive status epilepticus masquerading as hepatic encephalopathy: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jhun P, Kim H. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in hepatic encephalopathy. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:372-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jo YM, Lee SW, Han SY, Baek YH, Ahn JH, Choi WJ, Lee JY, Kim SH, Yoon BA. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus disguising as hepatic encephalopathy. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5105-5109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kaplan PW. The clinical features, diagnosis, and prognosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Neurologist. 2005;11:348-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sutter R, Kaplan PW. Electroencephalographic criteria for nonconvulsive status epilepticus: Synopsis and comprehensive survey. Epilepsia. 2012;53 Suppl 3:1-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kanto J, Gepts E. Pharmacokinetic implications for the clinical use of propofol. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1989;17:308-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Suh SJ, Yim HJ, Yoon EL, Lee BJ, Hyun JJ, Jung SW, Koo JS, Kim JH, Kim KJ, Choung RS, Seo YS, Yeon JE, Um SH, Byun KS, Lee SW, Choi JH, Ryu HS. Is propofol safe when administered to cirrhotic patients during sedative endoscopy? Korean J Intern Med. 2014;29:57-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vasile B, Rasulo F, Candiani A, Latronico N. The pathophysiology of propofol infusion syndrome: A simple name for a complex syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1417-1425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 427] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |