Published online Sep 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i17.2597

Peer-review started: April 10, 2019

First decision: May 9, 2019

Revised: July 2, 2019

Accepted: July 20, 2019

Article in press: July 20,2019

Published online: September 6, 2019

Processing time: 150 Days and 21.2 Hours

Moderately severe acute pancreatitis (MSAP) is a critical form of acute pancreatitis that is related with high morbidity and mortality. Severe Clostridium difficile infection (sCDI) is a serious and rare nosocomial diarrheal complication, especially in MSAP patients. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is a highly effective treatment for refractory and recurrent CDI (rCDI). However, knowledge regarding the initial use of FMT in patients suffering from sCDI is limited.

Here, we report an MSAP patient complicated with sCDI who was treated by FMT as a first-line therapy. The patient was a 51-year-old man who suffered from diarrhea in his course of acute pancreatitis. An enzyme immunoassay was performed to detect toxins, and the result was positive for toxin-producing C. difficile and toxin B and negative for C. difficile ribotype 027. The colonoscopy revealed pseudomembranous colitis. Due to these findings, sCDI was our primary consideration. Because the patient provided informed consent for FMT treatment, we initially treated the patient by FMT rather than metronidazole. Diarrhea resolved within 5 d after FMT. The patient remained asymptomatic, and the follow-up colonoscopy performed 40 d after discharge showed a complete recovery. Our case is the first reported in China.

This case explores the possibilities of initially using FMT to treat severe CDI. Moreover, FMT may become a critical component of the treatment for severe CDI in MSAP patients.

Core tip: A rare complication of acute pancreatitis is Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). Certain antibiotics are used as the treatment of choice for CDI. However, in our case, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) was considered the best treatment and achieved good results. This case demonstrates that FMT can be considered a first-line treatment for primary severe CDI in moderately severe acute pancreatitis patients.

- Citation: Hu Y, Xiao HY, He C, Lv NH, Zhu L. Fecal microbiota transplantation as an effective initial therapy for pancreatitis complicated with severe Clostridium difficile infection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(17): 2597-2604

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i17/2597.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i17.2597

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) infection (CDI) is the most common cause of diarrhea in resident patients, and its incidence, morbidity, mortality, and likelihood of recurrence are increasing[1]. CDI has become an important healthcare-associated infection with a considerable economic impact worldwide. CDI causes post-antibiotic associated diarrhea and colitis from dysbiosis due to the overgrowth of C. difficile. Certain antibiotic therapy remains the treatment of choice[2]. Moderately severe acute pancreatitis (MSAP) is characterized by transient organ failure or local or systemic complications without persistent organ failure[3]. However, in recent years, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has emerged as a new treatment method that is highly effective for the treatment of recurrent and refractory CDI (rCDI)[4]. To date, limited data have been available demonstrating that FMT is more cost-effective than some antibiotics as a first-line treatment for the first episode of severe CDI, especially in the treatment of MSAP patients. Here, we report a patient suffering from MSAP with hospital-acquired CDI who was completely cured by FMT after the first CDI episode.

Persistent upper abdominal pain for 5 d.

A 51-year-old man was admitted to our Intensive Care Unit (ICU) after 5 d of persistent severe upper abdominal pain. On day 9 after admission to the hospital, diarrhea developed with a frequency of 4-10 times/d. We stopped all treatments (rhubarb, mirabilite, and mannitol, oral; glycerol enema) that could induce diarrhea and administered montmorillonite and probiotics (Medilac-s, Live Combined Bacillus Subtilis and Enterococcus Faecium Enteric-coated Capsules 500 mg, t.i.d). However, the amount and frequency of diarrhea remained unrelieved.

The patient had a history of chronic consumption of large amounts of alcohol (approximately 80 g/d), had no significant prior medical history, and denied any history of drug use or smoking.

The patient’s family history was unremarkable.

Upon admission, the physical examination showed a pulse rate of 90 beats per minute, blood pressure of 120/70 mmHg , body temperature of 36.5 °C, and respiration rate of 23 breaths per minute. Pulse oxygen saturation was normal (96%). Moderate tenderness pain in the upper abdomen was observed without rebound tenderness; the results of bilateral chest percussion revealed dullness, and the lower lung breathing sounds disappeared; and the bedside ultrasound showed bilateral pleural effusion. Heart auscultation did not find anything. No jaundice was observed in the skin and sclera. After diarrhea occurred, rectal palpation was negative. The macroscopic aspects of the stools were yellow water-like stool.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed the following findings: Necrotizing pancreatitis, CT Severity Index (CTSI) level D, and a pancreatic necrotic area < 30% (Figure 1).

The laboratory analysis of the blood tests showed that many inflammatory markers were elevated (Table 1). The stool cultures were negative, and the fecal occult blood test scored 3+. An enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (GeneXpert, Cepheid, America) was performed to detect toxins, and the results were positive for toxin-producing C. difficile and toxin B and negative for C. difficile ribotype 027.

| Testing item | Results | Reference range |

| WBC, count/mL | 12360 | 3500-9500 |

| HCT, % | 46.9 | 43-58.0 |

| Serum amylase, IU/L | 156 | 20-110 |

| c(Ca2+), mmol/L | 1.79 | 2.11-2.52 |

| CRP, mg/L | 141 | <10 |

| Alb, g/L | 26.8 | 40.0-55.0 |

| LDH, U/L | 529 | 120-250 |

| FBG, mmol/L | 5.86 | 3.9-6.1 |

| ESR, mm/h | 69 | <20 |

| HIV | (-) | (-) |

| HBsAg | (-) | (-) |

| HCV-Ab | (-) | (-) |

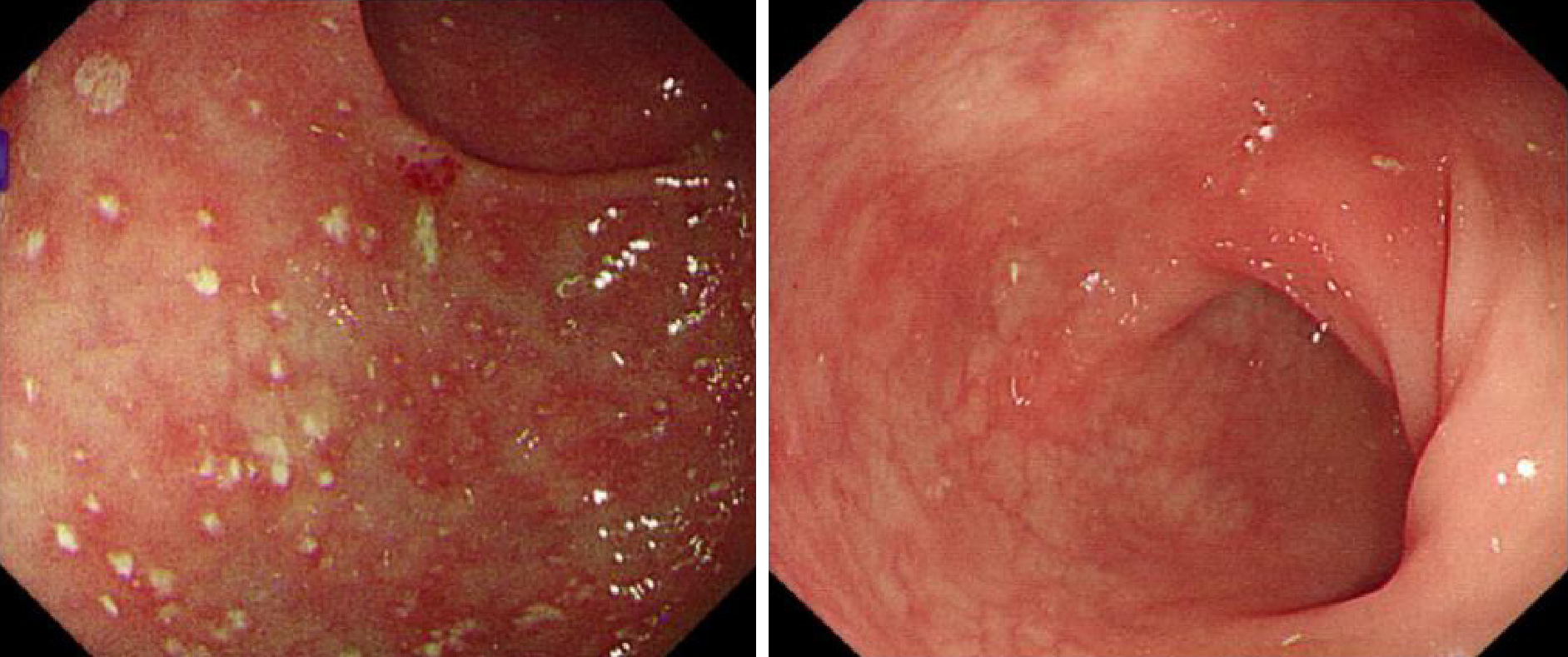

The preliminary combined results indicated MSAP according to the revised Atlanta classification[3]. Colonoscopy revealed pseudomembranous colonitis with yellow pseudomembranes on the wall of the transverse colon and descending colon (Figure 2A). In addition, HE staining revealed the presence of a pseudomembrane composed of an exudate made of inflammatory debris and white blood cells; Gram staining revealed the presence of Gram-positive bacilli. These results combined with the pathological and endoscopic characteristics led to a final diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis due to severe CDI.

We administered the routine treatments of fasting, gastric decompression, fluid resuscitation, and early enteral nutrition (EN); moreover, thoracic puncture and drainage were performed. The drugs administered included omeprazole (20 mg iv qd), ulinastatin (10 WU, q8 h, iv), somatostatin (0.5 mg/h, iv), an analgesic (butorphanol tartrate 3 mg/h, iv) as needed, catharsis (rhubarb, mirabilite, and mannitol, oral; glycerol enema), and a subcutaneous insulin injection for hyperglycemia. After these treatments, the patient clearly improved and was moved from the ICU. Because there was no evidence of pancreatic infection, no antibiotics were administered during hospitalization.

After CDI was diagnosed, we performed FMT on hospitalization day 20. The following abnormal laboratory finding was revealed before performing FMT: hemoglobin 116 g/L.

Fresh stool (50 g) from a donor was collected on the day of infusion, diluted with 200 mL sterile saline, and stirred in a blender (NJM-9060; NUC Electronics, Daegu, South Korea). The homogenized solution was filtered twice through a re-sterilized metal sieve. The sample was centrifuged, and the precipitate was dissolved in 200 mL normal saline twice. The final filtrates (200 mL) were infused into the patient via a nasal-jejunal tube. Before applying FMT, the patient was provided relevant knowledge and was required to fast for 1 h before the operation and 1 h after the operation. The infusion of the donor feces was performed three times (once every two days).

The stool donor for the FMT was a graduate student, who had no familial relationship with the patient. The donor was negative for blood-borne communicable diseases, and the stool tests were also negative for HBsAg, HCV-Ab, VDRL, HEV-IgM, HIV, CMV, syphilis, C. difficile toxin, roundworm, pinworm, hookworm, amoeba, and duovirus. The donor had no history of antibiotic use or any chemotherapy within the past year.

By the day after the second FMT, the frequency of diarrhea had dropped to twice a day, and the diarrhea resolved 5 d after the completion of the FMT process. During the treatment, the patient did not report any adverse events. The patient left the hospital on day 25. After 40 d, a follow-up EIA for toxins did not detect toxin-producing C. difficile, toxin B, or C. difficile ribotype 027. Meanwhile, the follow-up colonoscopy showed that the bowel was normal (Figure 2B).

Our case shows that FMT can be a potential treatment option as a first-line treatment for severe CDI.

The Unites States data showed that the incidence of CDI had gradually increased from 30 per 100000 in 1996 to 84 per 100000 in 2005[5]. A cohort study showed that the prevalence of this epidemic in AP patients significantly increased from 386 per 100000 in 1998 to 576 per 100000 in 2012, and CDI increases the mortality of and economic burden on patients with AP[6]. However, to date, only a few reports of the treatment of CDI in patients with AP have been published.

We speculate that the causes of dysbacteriosis in our patient were as follows: (1) History of excessive alcohol consumption; (2) A hospital stay longer than 7 d for MSAP; (3) Gut barrier dysfunction; and (4) A high carbohydrate intake. We did not perform a confirmation test, which might have revealed a toxigenic culture, because the patient had a very particular diarrhea symptom, endoscopic findings, and positive toxin detection. According to the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID)[7], a two-stage test [glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) or nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for toxin genes, followed by a highly sensitive toxin test or GDH in combination with a toxin test] is recommended for the diagnosis of CDI. We performed the NAATs (Xpert) and toxin B EIA test, and both tests were positive; thus, we believe that CDI was most likely present. However, we used enteroscopy as another diagnostic tool in this patient because we thought that he might have other causes for the severe diarrhea, which is consistent with the indications for enteroscopy in patients with CDI[8]. According to the ESCMID guidelines[9], pseudomembranous colitis can support the diagnosis of severe CDI in our case.

There was no evidence of infection in our AP patient, and antibiotics may result in adverse events, affecting the patient's prognosis and prolonging the hospitalization time. Additionally, FMT is still in the preliminary stage of research at our center and is free of charge. Therefore, FMT was our first choice of treatment for this patient. Various options were discussed in length with the patient and his family. We agree that choosing FMT management instead of antibiotics in primary CDI is controversial. In recent years, with the deepening understanding of the pathogenesis of CDI in the medical community, great changes have been implemented in the management of CDI. Initially, metronidazole was mainly used as a first-line management[10]. Data before 2000 demonstrated that the proportion of patients receiving metronidazole to achieve a clinical cure was similar to the group of receiving vancomycin. However, recent data show that vancomycin had a significant effect on both symptom relief and a lower recurrence rate[11]. While antibiotics have been the mainstay of CDI treatment for decades, the increase in CDI frequency, severity, and treatment failures has prompted investigations into the development of alternative therapies that are less disruptive to the colonic microbiota. This effect may be driven by the resistance patterns of the bacteria. FMT is currently an alternative recommended option in select guidelines[4] due to more and more evidence suggesting efficacy. Unfortunately, because data regarding the use of FMT in initial CDI episodes are limited, FMT is currently recommended only for the treatment of recurrent CDI infections. Based on this background, we discussed the advantages and disadvantages with the patient and obtained written informed consent from the patient and his family. We may consider how to choose drugs if vancomycin gradually lost its current therapeutic effect as metronidazole did, as FMT has no drug resistance problem. The strategy that not all people at risk of or with CDI need enduring antibiotic treatment suggests why FMT is a potential and much needed additional treatment approach. Indeed, more relevant clinical studies are needed to conquer the epidemic.

From an evidence-based perspective, to date, there is insufficient evidence to recommend FMT as an initial treatment for the first episode of CDI[4]. We searched MEDLINE for articles published in English from 1980 to January 2019 involving human participants that described the use of FMT to treat primary CDI (Table 2). We did not restrict the search on the basis of the study design. We identified 10 patients treated with FMT during initial episodes of CDI, all of which were reported in case study series, and not enough data were published[12]. Nine patients were a part of a series involving 20 patients initially treated with FMT for primary CDI[13]; an overall response to treatment was achieved in seven patients in the transplantation group and five patients in the metronidazole group. In one case report, FMT achieved a good effect with no adverse events, although the approaches and methods differed from those used in our patients[14].

| Patient | Sex | Age(yr) | Complication | Antibiotics | EIA for toxins | Fecal material delivery | Adverseevents |

| 1 | M | 51 | MSAP | - | Positive for toxin- producing C. difficile and toxin B | Nasogastric tube | None |

| 2[16] | F | 64 | Dental pain and infections | Clindamycin | Positive for C. difficile toxin and GDH | Colonoscopy | None |

| 3[15] | F (4) M (5) | 67 (34-88) | - | Yes | Retention enema | (1) A foul smell from the patient's stool; (2) No clinical symptoms but an increase in the CRP levels a few days after treatment |

Our report supports the availability of FMT for the management of severe CDI as an initial therapy. In addition, some studies show that FMT is more cost-effective than antimicrobial therapy[15]. The dramatic effect of FMT shown here provides evidence of the important role of gut microbiota in maintaining homeostasis. There is evidence to support that healthy donors’ bacteria can restore the structure and function of the recipients’ intestinal microbial community[16]. FMT can not only eradicate C. difficile but also restore the potential defect of the fecal flora.

To the best of our knowledge, this article presents the first report of severe CDI complicating MSAP that was treated successfully via FMT in China; this article also presents a rare report of FMT used as a first-line treatment for new-onset severe CDI. As the risks of FMT are small and the potential benefits for severe ill patients are considerable, we advocate that the use of FMT in this patient population is reasonable. Furthermore, FMT may play a role in treating patients with SAP complicated with infections. However, fecal microbiota constitutes a highly complex material, and we do not precisely know which components are beneficial or potentially harmful. More trials assessing FMT as an initial treatment for sCDI are needed.

CDI occurs when normal intestinal flora is weakened and induces a severe clinical burden. Our case shows that the possibility of CDI should be considered when abnormal diarrhea occurs in a pancreatitis patient. Furthermore, FMT is equally effective in the initial CDI treatment and may become an alternative to antibiotic therapy in primary C. difficile infection, especially in AP patients.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Khuroo MS, Manenti A, Tantau A, Hoff DAL, Neri V S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Zhou BX

| 1. | Lessa FC, Winston LG, McDonald LC, Emerging Infections Program C. difficile Surveillance Team. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2369-2370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Peng Z, Ling L, Stratton CW, Li C, Polage CR, Wu B, Tang YW. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of Clostridium difficile infections. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018;7:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4342] [Article Influence: 361.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 4. | Cammarota G, Ianiro G, Tilg H, Rajilić-Stojanović M, Kump P, Satokari R, Sokol H, Arkkila P, Pintus C, Hart A, Segal J, Aloi M, Masucci L, Molinaro A, Scaldaferri F, Gasbarrini G, Lopez-Sanroman A, Link A, de Groot P, de Vos WM, Högenauer C, Malfertheiner P, Mattila E, Milosavljević T, Nieuwdorp M, Sanguinetti M, Simren M, Gasbarrini A; European FMT Working Group. European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut. 2017;66:569-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 853] [Cited by in RCA: 784] [Article Influence: 98.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile--more difficult than ever. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1932-1940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1035] [Cited by in RCA: 1023] [Article Influence: 60.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Trikudanathan G, Munigala S. Impact of Clostridium difficile infection in patients hospitalized with acute pancreatitis- a population based cohort study. Pancreatology. 2017;17:201-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Crobach MJ, Planche T, Eckert C, Barbut F, Terveer EM, Dekkers OM, Wilcox MH, Kuijper EJ. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the diagnostic guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22 Suppl 4:S63-S81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Burkart NE, Kwaan MR, Shepela C, Madoff RD, Wang Y, Rothenberger DA, Melton GB. Indications and Relative Utility of Lower Endoscopy in the Management of Clostridium difficile Infection. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011;2011:626582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Debast SB, Bauer MP, Kuijper EJ; European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the treatment guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20 Suppl 2:1-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 766] [Cited by in RCA: 793] [Article Influence: 72.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Paknikar R, Pekow J. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for the Management of Clostridium difficile Infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2018;19:785-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Johnson S, Louie TJ, Gerding DN, Cornely OA, Chasan-Taber S, Fitts D, Gelone SP, Broom C, Davidson DM; Polymer Alternative for CDI Treatment (PACT) investigators. Vancomycin, metronidazole, or tolevamer for Clostridium difficile infection: results from two multinational, randomized, controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:345-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 346] [Cited by in RCA: 391] [Article Influence: 35.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Brandt LJ, Borody TJ, Campbell J. Endoscopic fecal microbiota transplantation: "first-line" treatment for severe clostridium difficile infection? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:655-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Juul FE, Garborg K, Bretthauer M, Skudal H, Øines MN, Wiig H, Rose Ø, Seip B, Lamont JT, Midtvedt T, Valeur J, Kalager M, Holme Ø, Helsingen L, Løberg M, Adami HO. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Primary Clostridium difficile Infection. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2535-2536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tanaka T, Kato H, Fujimoto T. Successful Fecal Microbiota Transplantation as an Initial Therapy for Clostridium difficile Infection on an Outpatient Basis. Intern Med. 2016;55:999-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jiang M, Leung NH, Ip M, You JHS. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ribotype-guided fecal microbiota transplantation in Chinese patients with severe Clostridium difficile infection. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0201539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Seekatz AM, Aas J, Gessert CE, Rubin TA, Saman DM, Bakken JS, Young VB. Recovery of the gut microbiome following fecal microbiota transplantation. MBio. 2014;5:e00893-e00814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |