Published online Aug 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2374

Peer-review started: January 23, 2019

First decision: March 18, 2019

Revised: May 17, 2019

Accepted: June 26, 2019

Article in press: June 27, 2019

Published online: August 26, 2019

Processing time: 216 Days and 21.3 Hours

In recent years, the incidence of fungal infection has been increasing, often invading one or more systems of the body. However, it is rare for lymph nodes to be invaded without the involvement of other organs.

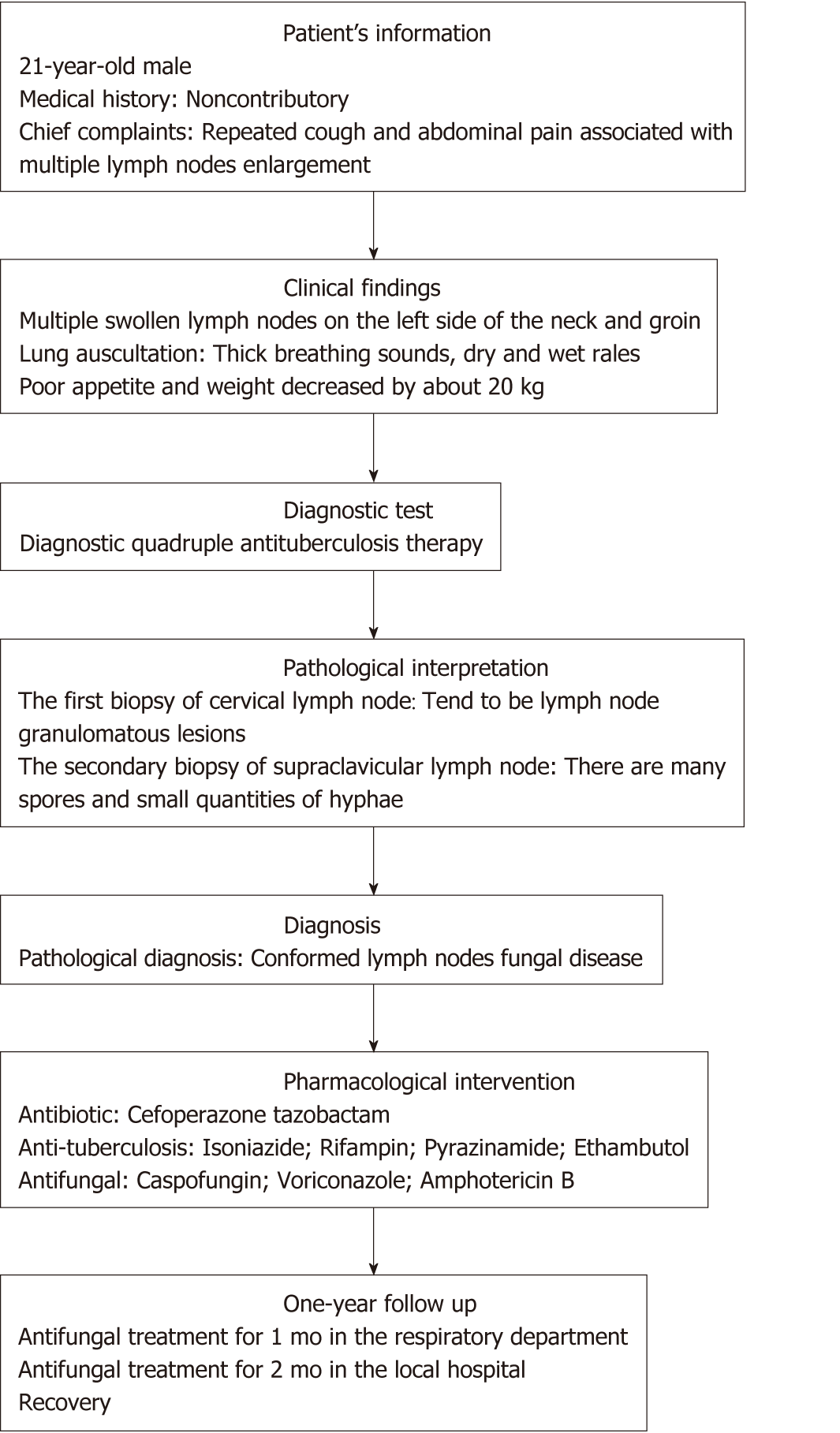

A 21-year-old man was admitted to hospital for repeated cough for 2 mo and abdominal pain for 1 mo. Physical examination revealed multiple lymph nodes enlargement, especially those in the left neck and groin. CT scan showed multiple lymph nodes enlargement in the chest, especially left lung, abdominal cavity, and retroperitoneum. The first lymph node biopsy revealed granulomatous lesions of lymph nodes, so intravenous infusion of Cefoperazone tazobactam combined with anti-tuberculosis drugs were given. Because fever and respiratory failure occurred 4 d after admission, mechanical ventilation was given, and Caspofungin and Voriconazole were used successively. However, the disease still could not be controlled. On the 11th day of admission, the body temperature reached 40° C. After mycosis of lymph nodes was confirmed by the second lymph node biopsy, Amphotericin B was given, and the patient recovered and was discharged from the hospital.

No fixed target organ was identified in this case, and only lymph node involvement was found. Caspofungin, a new antifungal drug, and the conventional first choice drug, Voriconazole, were ineffective, while Amphotericin B was effective.

Core tip: In this case, the results from cervical and supraclavicular lymph node biopsies were different. It is very difficult to diagnose lymph node mycosis quickly in the early stage. When conventional anti-infective treatment is ineffective, multi-stage and multi-site lymph node biopsy is particularly important. The new antifungal drug Caspofungin and the empirical antifungal agent Voriconazole were ineffective, and successful treatment was achieved with Amphotericin B.

- Citation: Xiao XF, Wu JX, Xu YC. Treatment of invasive fungal disease: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(16): 2374-2383

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i16/2374.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2374

Invasive fungal disease (IFD) is a common type of infection in daily clinical practice around the world. It is defined as fungus that invades body tissues, fluids, and blood, and its growth in these places causes inflammation reaction, leading to tissue damage and organ dysfunction. The incidence in patients with immunosuppression due to organ transplants, malignant tumors, etc is high (up to 20%-40%)[1]. In recent years, with increasing numbers of immunosuppression in patients with diseases (e.g., malignant tumors and acquired immune deficiency syndrome) and those who use immunosuppressive drugs, IFD incidence has increased dramatically, and the proportion is higher in patients with chronic diseases[2-6]. Current estimates suggest that there are approximately 300 million life-threating fungal infections annually, resulting in 1.6 million deaths[7]. Health impacts worldwide include high morbidity, an overall mortality of 30%–80%, and a multibillion dollar annual economic burden[8].

Lung is the most common target organ of fungal infection. Some specific fungi also have corresponding sensory organs. For example, Aspergillus often diffuses in the brain, candida infection often appears in mucositis, and cryptococcal infection often involves the central nervous system[9]. However, it is not common that the main manifestation is lymph node invasion. Unlike previously reported cases, we report a case of invasive mycosis with lymph node fungal infection as the predominant manifestation in a non-immunodeficient patient.

A 21-year-old man presented to the emergency room department with the chief complaints of repeated cough and abdominal pain associated with multiple lymph nodes enlargement.

The patient began to cough and expectorate 2 mo ago, but he refused treatment at that time. These symptoms continued to appear repeatedly. One month ago, he felt pain in his abdominal region with persistence of colic and paroxysmal exacerbation. There were many lymph nodes on the left side of his neck and groin, but there was no fever over the course of disease. His appetite was poor, and his weight decreased approximately 20 kg in 2 mo.

There were no significant comorbidities at admission.

The patient was unmarried and childless, lived in a good environment. He denied smoking or drinking and had no personal or family history of other diseases.

Clinical examination revealed the presence of multiple swollen lymph nodes, especially on the left side of his neck and groin. The lymph nodes looked like peanuts with moderate hardness, and their borders were clear. There were no adhesions in the surrounding tissues, and an absence of tenderness. Lung auscultation revealed thick breathing sounds and dry and wet rales.

Laboratory results including liver function, renal function, electrolytes, enzymology, and immunological tests, such as lymphocyte subsets, immunoglobulin, and immunoelectrophoresis, were normal. Blood culture, parasite detected, sputum acid fast staining, virology examination, rheumatoid factor tests, tuberculosis-antibody immunoglobulin G, tuberculosis-antibody immunoglobulin M tests, and human immunodeficiency virus (1+2) antibodies were negative. White cell count, neutrophil ratio, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were elevated, and sputum culture showed Klebsiella pneumoniae.

The computed tomography showed there were many enlarged lymph nodes in the chest and abdominal cavity, with some distributed in the retroperitoneal space. We also found pulmonary atelectasis and infection in the left lung (Figure 1, Videos 1-3).

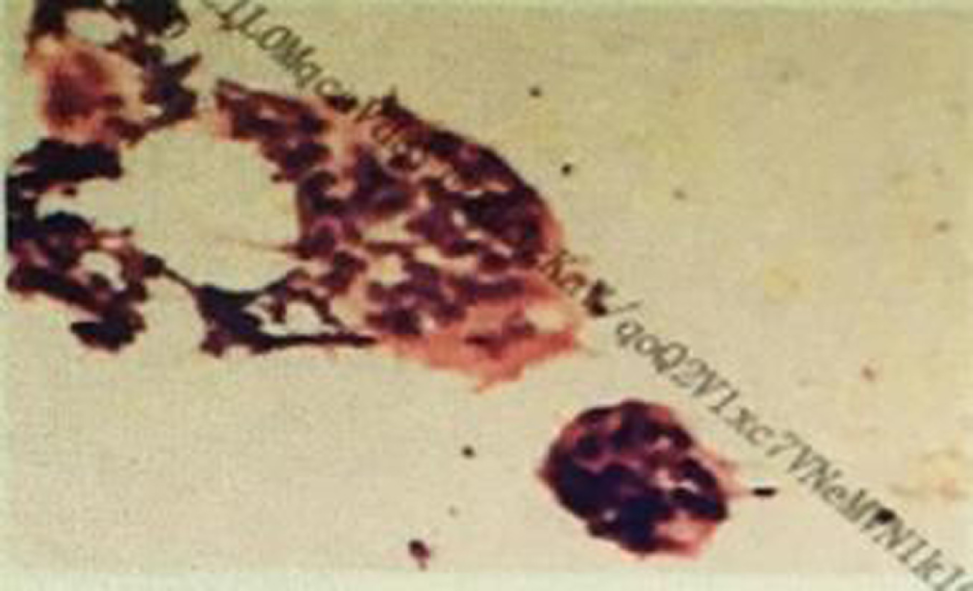

In the first biopsy of the cervical lymph node, we found a few lymphocytes and multinucleated giant cells, with no tumor cells, and there tended to be lymph node granulomatous lesions (Figure 2).

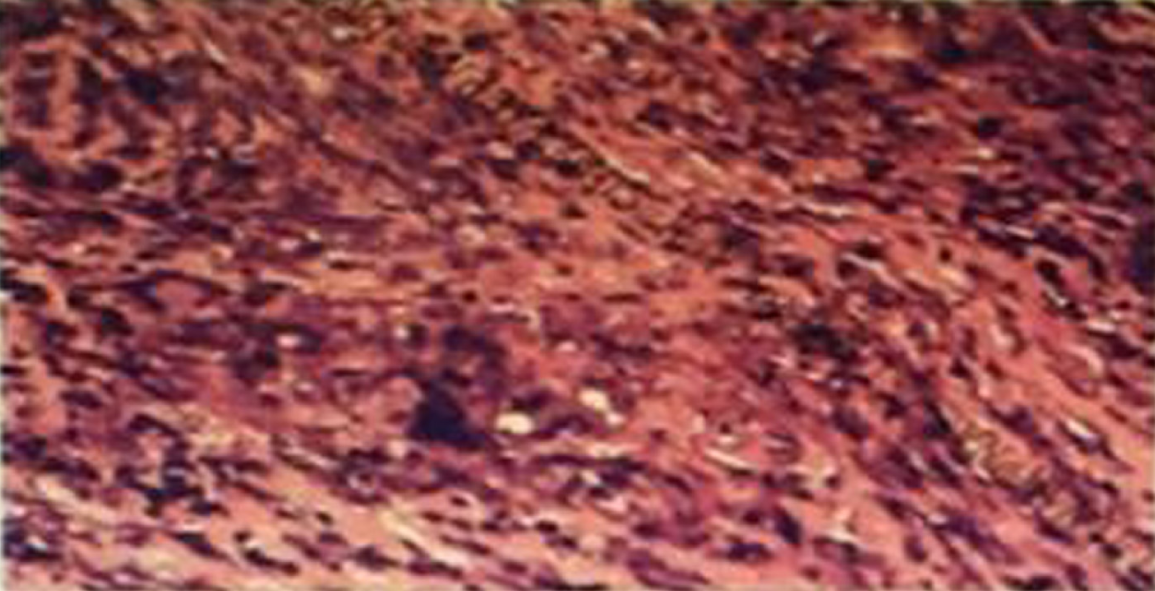

In the second biopsy of the supraclavicular lymph node, we found lymph nodes with widespread degeneration and necrosis, and there were many spores and small quantities of hyphae in these tissues. There were many giant cell granulomas in the peripheral lymphoid tissues (Figure 3).

Bronchoscopy showed bilateral bronchial mucous that was uneven with hyperemia and edema. In addition, there were some small white ulcers. Blood samples as well as white glutinous secretions with filaments were seen in the airway.

Based on the imaging findings and the results of the secondary lymph node biopsy, the patient was finally diagnosed with mycosis of lymph nodes.

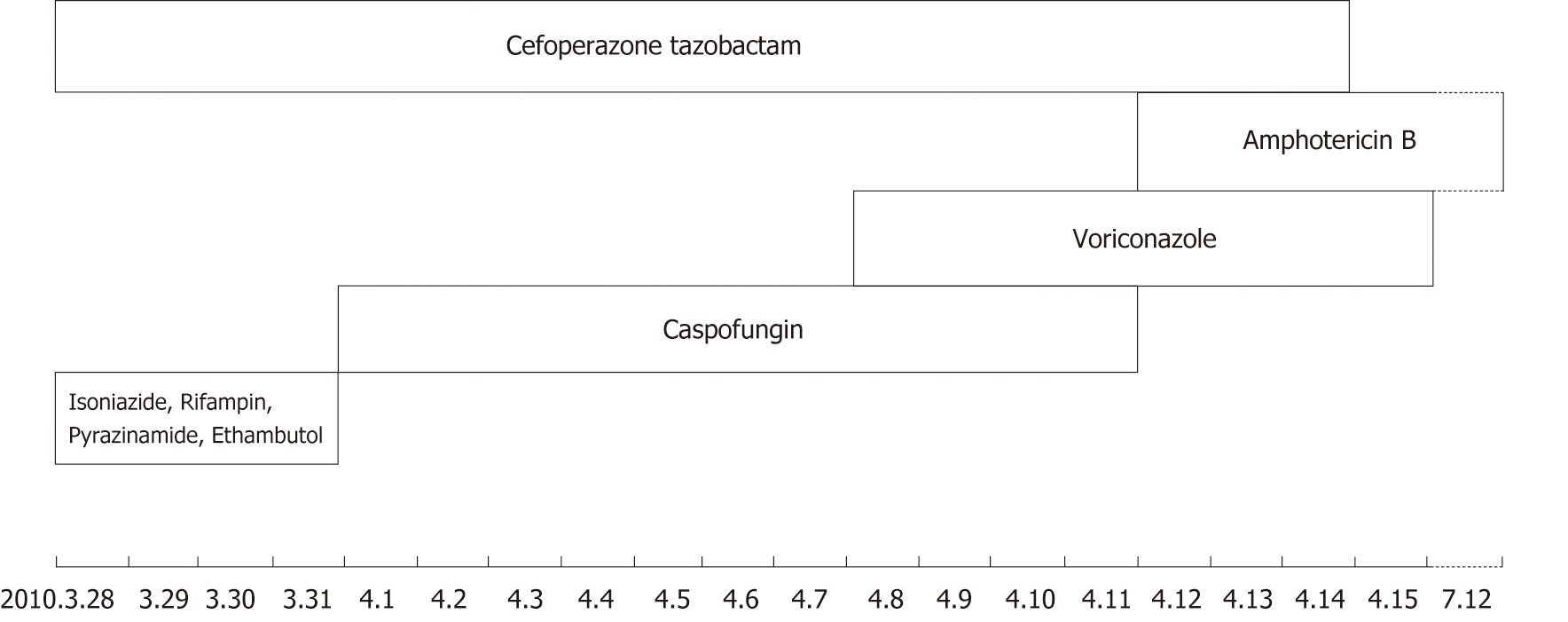

After admission, he received regular antibiotic treatment and anti-tuberculosis treatment (Cefoperazone tazobactam 2 × 2 g/d,intravenous drip; Isoniazide 0.3 g; Rifampin 0.45 g; Pyrazinamide 3 × 0.5 g; Ethambutol 0.75 g/d, PO), but the treatment effect was not ideal. His temperature was raised gradually in the fifth day, and he started to present with respiratory failure (the oxygenation index less than 150 mmHg) and needed mechanical ventilation therapy. The general anti-infection and anti-tuberculosis treatment were invalid, so we stopped giving anti-tuberculosis drugs and switched to antifungal therapy using Caspofungin (50 mg/d, intravenous drip) for 7 d. The patient’s temperature, however, was still not under control. Therefore, we added Voriconazole (2 × 0.2 g/d, intravenous drip) to his treatment. Four days later, this change appeared to be invalid, and the patient’s temperature continued to rise. Then we conducted another lymph node biopsy (Figure 2), and at the same time, we began Amphotericin B (30 mg/d, intravenous drip) as the antifungal treatment and stopped using Caspofungin. As Amphotericin B was gradually added, Voriconazole was discontinued after 4 d of Amphotericin B. Figure 4 shows the timeline of drug intervention.

On the third day of Amphotericin B treatment, the patient’s temperature gradually returned to normal, and respiratory failure relieved. On the 15th day after admission, the patient was evacuated from the ventilator, and his condition tended to improve. He was then transferred out of the intensive care unit. After continued antifungal treatment for 1 mo in the respiratory department, he went back to the local hospital for further antifungal treatment for 2 mo and recovered. Figure 5 represents the timeline from the patient’s presentation to the final outcome.

Clinical manifestations in fungal infection are various and lack of specificity, and they often appear in conjunction with other diseases and are easily concealed by the primary diseases. In general, the lung is the most common target organ in fungal infection. Some specific fungi also have corresponding target organs: Aspergillomycosis often spreads in the brain; mucosal inflammation is the most common manifestations in candidiasis; and cryptococcosis always involves central nervous system[9]. Onychomycosis is considered to be one of the hallmarks of human immunodeficiency virus[10]. However, swollen lymph nodes as the prominent manifestation are not common in fungal infections.

Many new antifungal drugs and dosage forms have been developed in recent years, but the incidence and mortality of IFD remains high[2,11-14]. It has been reported that the mortality rates exceed 30% in patients diagnosed with IFD[15]. In recent years, diagnostic testing has improved significantly, and the determination of some biomarkers, such as procalcitonin and presepsin, play an important role in the identification of fungal or bacterial infections[16-19]. However, accurate diagnosis of IFD remains challenging. Fungal infections lack specific characteristic clinical manifestations and laboratory indicators, making early diagnosis difficult and the rate of missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis high[11]. In this case, the patient was young and had no history of tumor or other immunodeficiency. The first lymph node biopsy indicated lymph node granulomatous lesions, where there is no specificity. Therefore, the implementation of empirical anti-bacterial and diagnostic anti-tuberculosis treatment was made. Obviously, there was no effect and the patient's condition gradually worsened, with onset of fever, shortness of breath, and the need for mechanical ventilation treatment. When conventional anti-infective treatment is ineffective or the disease advances progressively, the possibility of fungal infection should be taken into consideration. Antifungal treatment should be given appropriately, and lymph node biopsy should be performed again to find the pathogen.

Clarity and uniformity in defining these infections are important. At present, invasive fungal infection is mainly diagnosed by grading mode[1]. The diagnostic basis is composed of four parts: Host (risk) factors, clinical evidence, mycological evidence, and histopathological evidence[1]. The diagnostic level can be divided into three grades: Definite diagnosis, clinical diagnosis, and suspected diagnosis[1]. Diagnostic criteria are shown in Tables 1-3[1]. Infections caused by Pneumocystis jirovec are not included. The criteria for definite diagnosis and clinical diagnosis (Tables 1 and 2)[1] include indirect tests, whereas the level of suspected diagnosis (Table 3)[1] include fungal etiology, although mycological evidence is lacking. These definitions have been adopted by most practice guidelines for IFD. The most commonly identified fungal species associated with IFD are Candida species, Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, and Pneumocystis[20]. This case accorded with the grade of suspected diagnosis according to this standard. As there was no etiological basis, Caspofungin with relatively few side effects was given. In this case, Caspofungin was given first and then combined with Voriconazole. Voriconazole is the preferred antifungal drug for empirical antifungal therapy[21]. Unfortunately, the patient's condition was not effectively controlled, and fever occurred (the body temperature rose to 40° C). At this point, lymph nodes biopsy was again carried out, revealing lymph node mycosis. The diagnosis of fungal infection was clear, but empirical antifungal therapy was ineffective. At this point, Amphotericin B was resolutely replaced for treatment, and the patient eventually recovered. However, due to technical limitations, we failed to clear the specific type of the fungal infection. Detection and characterization of drug resistance in vitro could assist clinicians to select the best antifungal regimen[8]. Evidence supports therapeutic drug monitoring to optimize clinical efficacy[22,23], and our future research efforts will focus on optimization this strategy.

| Analysis and specimen | Molds1 | Yeasts1 |

| Microscopic analysis: Sterile material | Histopathologic, cytopathologic, or direct microscopic examination2 of a specimen obtained by needle aspiration or biopsy in which hyphae or melanized yeast-like forms are seen accompanied by evidence of associated tissue damage | Histopathologic, cytopathologic, or direct microscopic examination2 of a specimen obtained by needle aspiration or biopsy from a normally sterile site (other than mucous membranes) showing yeast cells - for example, Cryptococcus species indicated by encapsulated budding yeasts or Candida species showing pseudohyphae or true hyphae3 |

| Culture; Sterile material | Recovery of a mold or “black yeast” by culture of a specimen obtained by a sterile procedure from a normally sterile and clinically or radiologically abnormal site consistent with an infectious disease process, excluding bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, a cranial sinus cavity specimen, and urine | Recovery of a yeast by culture of a sample obtained by a sterile procedure [including a freshly placed (< 24 h ago) drain] from a normally sterile site showing a clinical or radiological abnormality consistent with an infectious disease process |

| Blood | Blood culture that yields a mold4 (e.g., Fusarium species) in the context of a compatible infectious disease process | Blood culture that yields yeast (e.g., Cryptococcus or Candida species) or yeast- like fungi (e.g., Trichosporon species) |

| Serological analysis: CSF | Not applicable | Cryptococcal antigen in CSF indicates disseminated cryptococcosis |

| Host factors1 |

| Recent history of neutropenia [< 0.5 × 109 neutrophils/L (< 500 neutrophils/mm3] for > 10 d] temporally related to the onset of fungal disease |

| Receipt of an allogeneic stem cell transplant |

| Prolonged use of corticosteroids (excluding among patients with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis) at a mean minimum dose of 0.3 mg/kg/d of prednisone equivalent for > 3 wk |

| Treatment with other recognized T cell immunosuppressants, such as cyclosporine, TNF-α blockers, specific monoclonal antibodies (such as alemtuzumab), or nucleoside analogues during the past 90 d |

| Inherited severe immunodeficiency (such as chronic granulomatous disease or severe combined immunodeficiency) |

| Clinical criteria2 |

| Lower respiratory tract fungal disease3 |

| The presence of one of the following three signs on CT: |

| Dense, well-circumscribed lesions(s) with or without a halo sign |

| Air-crescent sign |

| Cavity |

| Tracheobronchitis |

| Tracheobronchial ulceration, nodule, pseudomembrane, plaque, or eschar seen on bronchoscopic analysis |

| Sinonasal infection |

| Imaging showing sinusitis plus at least one of the following three signs: |

| Acute localized pain (including pain radiating to the eye) |

| Nasal ulcer with black eschar |

| Extension from the paranasal sinus across bony barriers, including into the orbit |

| CNS infection |

| One of the following two signs: |

| Focal lesions on imaging |

| Meningeal enhancement on MRI or CT |

| Disseminated candidiasis4 |

| At least one of the following two entities after an episode of candidemia within the previous 2 wk: |

| Small, target-like abscesses (bull's-eye lesions) in liver or spleen |

| Progressive retinal exudates on ophthalmologic examination |

| Mycological criteria |

| Direct test (cytology, direct microscopy, or culture) |

| Mold in sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, bronchial brush, or sinus aspirate samples, indicated by 1 of the following: |

| Presence of fungal elements indicating a mold |

| Recovery by culture of a mold (e.g., Aspergillus, Fusarium, Zygomycetes, or Scedosporium species) |

| Indirect tests (detection of antigen or cell-wall constituents)5 |

| Aspergillosis |

| Galactomannan antigen detected in plasma, serum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, or CSF |

| Invasive fungal disease other than cryptococcosis and zygomycoses |

| β-D-glucan detected in serum |

| Diagnosis and criteria |

| Proven endemic mycosis |

| In a host with an illness consistent with an endemic mycosis, one of the following: |

| Recovery in culture from a specimen obtained from the affected site or from blood |

| Histopathologic or direct microscopic demonstration of appropriate morphologic forms with a truly distinctive appearance characteristic of dimorphic fungi, such as Coccidioides species spherules, Blastomyces dermatitidis thick-walled broad-based budding yeasts, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis multiple budding yeast cells, and, in the case of histoplasmosis, the presence of characteristic intracellular yeast forms in a phagocyte in a peripheral blood smear or in tissue macrophages |

| For coccidioidomycosis, demonstration of coccidioidal antibody in CSF, or a 2-dilution rise measured in two consecutive blood samples tested concurrently in the setting of an ongoing infectious disease process |

| For paracoccidioidomycosis, demonstration in two consecutive serum samples of a precipitin band to paracoccidioidin concurrently in the setting of an ongoing infectious disease process |

| Probable endemic mycosis |

| Presence of a host factor, including but not limited to those specified in Table 2, plus a clinical picture consistent with endemic mycosis and mycological evidence, such as a positive Histoplasma antigen test result from urine, blood, or CSF |

IFDs are characterized by insidious onset and lack of specificity of symptoms. Early neglect can cause delay of diagnosis and treatment, resulting in critical illness and life threatening complications. Therefore, effective antifungal therapy should be carried out once the definite diagnosis/clinical diagnosis is confirmed, and empirical antifungal therapy should also be carried out in the early stage for patients of suspected diagnosis with unclear pathogens. When empiric antifungal therapy is ineffective, it is important to change the antifungal drugs decisively. The patient eventually recovered and was discharged from the hospital, benefiting from early and timely empirical antifungal treatment, although ineffective, but winning the time and opportunity for the latter irrigation of changing antifungal drugs.

In summary, invasive mycosis is a common medical problem in the world. The positive rate of lymph node biopsy is not high. Once invasive fungal infection occurs, it is often accompanied by severe condition, long course, high medical cost, and poor prognosis. In addition, IFD has been shown to be a substantial financial burden to the health care system[24,25]. Therefore, multi-stage and multi-site lymph node biopsies are the key to the diagnosis of the disease. Timely and effective antifungal treatment is essential for curing the disease.

The possibility of fungal infection should be considered when both empirical anti-infection and diagnostic anti-tuberculosis treatments are ineffective. The new antifungal drug was not the best treatment, and the empirical antifungal drugs do not necessarily work for every patient. Precise individualized treatment is needed. When routine antifungal therapy is invalid, it is appropriate to change the drug. When replacing antifungal drugs, it is necessary to consider the overlap and continuity of drugs.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cuevas-Covarrubias SA, Kaliyadan F S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, Pappas PG, Maertens J, Lortholary O, Kauffman CA, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Maschmeyer G, Bille J, Dismukes WE, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Kibbler CC, Kullberg BJ, Marr KA, Muñoz P, Odds FC, Perfect JR, Restrepo A, Ruhnke M, Segal BH, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC, Viscoli C, Wingard JR, Zaoutis T, Bennett JE; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1813-1821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4096] [Cited by in RCA: 3953] [Article Influence: 232.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive mycoses in North America. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2010;36:1-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 660] [Cited by in RCA: 670] [Article Influence: 44.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lortholary O, Gangneux JP, Sitbon K, Lebeau B, de Monbrison F, Le Strat Y, Coignard B, Dromer F, Bretagne S; French Mycosis Study Group. Epidemiological trends in invasive aspergillosis in France: the SAIF network (2005-2007). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1882-1889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schelenz S. Management of candidiasis in the intensive care unit. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61 Suppl 1:i31-i34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Guinea J, Torres-Narbona M, Gijón P, Muñoz P, Pozo F, Peláez T, de Miguel J, Bouza E. Pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:870-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hayes GE, Denning DW. Frequency, diagnosis and management of fungal respiratory infections. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:259-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stop neglecting fungi. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Beardsley J, Halliday CL, Chen SC, Sorrell TC. Responding to the emergence of antifungal drug resistance: perspectives from the bench and the bedside. Future Microbiol. 2018;13:1175-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tang S; Chinese Medical Association The Editorial Board, Chinese Journal of Pediatrics; Subspecialty Group of Hematology The Society of Pediatrics The Society of Pediatrics; Chinese Medical Association The Editorial Board Chinese Journal of Pediatrics; Subspecialty Group of Hematology, The Society of Pediatrics, The Society of Pediatrics. [Treatment recommendations for invasive fungal disease in pediatric patients with cancer or blood disease]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2014;52:426-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ameen M, Lear JT, Madan V, Mohd Mustapa MF, Richardson M. British Association of Dermatologists' guidelines for the management of onychomycosis 2014. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:937-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schelenz S, Barnes RA, Barton RC, Cleverley JR, Lucas SB, Kibbler CC, Denning DW; British Society for Medical Mycology. British Society for Medical Mycology best practice recommendations for the diagnosis of serious fungal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:461-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nivoix Y, Velten M, Letscher-Bru V, Moghaddam A, Natarajan-Amé S, Fohrer C, Lioure B, Bilger K, Lutun P, Marcellin L, Launoy A, Freys G, Bergerat JP, Herbrecht R. Factors associated with overall and attributable mortality in invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1176-1184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dignani MC. Epidemiology of invasive fungal diseases on the basis of autopsy reports. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Miceli MH, Lee SA. Emerging moulds: epidemiological trends and antifungal resistance. Mycoses. 2011;54:e666-e678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bitar D, Lortholary O, Le Strat Y, Nicolau J, Coignard B, Tattevin P, Che D, Dromer F. Population-based analysis of invasive fungal infections, France, 2001-2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1149-1155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pieralli F, Corbo L, Torrigiani A, Mannini D, Antonielli E, Mancini A, Corradi F, Arena F, Moggi Pignone A, Morettini A, Nozzoli C, Rossolini GM. Usefulness of procalcitonin in differentiating Candida and bacterial blood stream infections in critically ill septic patients outside the intensive care unit. Intern Emerg Med. 2017;12:629-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Thomas-Rüddel DO, Poidinger B, Kott M, Weiss M, Reinhart K, Bloos F; MEDUSA study group. Influence of pathogen and focus of infection on procalcitonin values in sepsis patients with bacteremia or candidemia. Crit Care. 2018;22:128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bamba Y, Moro H, Aoki N, Koizumi T, Ohshima Y, Watanabe S, Sakagami T, Koya T, Takada T, Kikuchi T. Increased presepsin levels are associated with the severity of fungal bloodstream infections. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0206089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lippi G. Sepsis biomarkers: past, present and future. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2019; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Schmiedel Y, Zimmerli S. Common invasive fungal diseases: an overview of invasive candidiasis, aspergillosis, cryptococcosis, and Pneumocystis pneumonia. Swiss Med Wkly. 2016;146:w14281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Infectious Diseases Society of Taiwan. ; Hematology Society of Taiwan; Taiwan Society of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine; Medical Foundation in Memory of Dr Deh-Lin Cheng; Foundation of Professor Wei-Chuan Hsieh for Infectious Diseases Research and Education; CY Lee’s Research Foundation for Pediatric Infectious Diseases and Vaccines. Guidelines for the use of antifungal agents in patients with invasive fungal infections in Taiwan--revised 2009. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43:258-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Andes D, Pascual A, Marchetti O. Antifungal therapeutic drug monitoring: established and emerging indications. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:24-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Stott KE, Hope WW. Therapeutic drug monitoring for invasive mould infections and disease: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:i12-i18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zaoutis TE, Argon J, Chu J, Berlin JA, Walsh TJ, Feudtner C. The epidemiology and attributable outcomes of candidemia in adults and children hospitalized in the United States: a propensity analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1232-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 575] [Cited by in RCA: 600] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zaoutis TE, Heydon K, Chu JH, Walsh TJ, Steinbach WJ. Epidemiology, outcomes, and costs of invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised children in the United States, 2000. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e711-e716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |