Published online Aug 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2336

Peer-review started: March 20, 2019

First decision: June 21, 2019

Revised: July 25, 2019

Accepted: July 27, 2019

Article in press: July 27, 2019

Published online: August 26, 2019

Processing time: 162 Days and 15.3 Hours

Abdominal drainage allows for timely detection of hemorrhage, but it cannot prevent hemorrhage. Whether routine abdominal drainage is needed during bariatric procedures remains controversial. Few reports describe the role of abdominal drainage in the diagnosis and treatment of abdominal hemorrhage in bariatric surgery.

Six cases of hemorrhage after bariatric surgery were described, including three cases with and three without abdominal drainage during the first surgery. The hemorrhage in five of the six cases was controlled by conservative treatment. Abdominal hemorrhage was found through the drainage tube on the day of the operation in the three patients with abdominal drainage during the first surgery. Emergency treatment was initiated, and their conditions gradually stabilized within 48 h. No patients required a reoperation. Abdominal hemorrhage was found later in the patients without abdominal drainage. Although the hemorrhage was controlled by conservative treatment in two cases (1 and 2), reoperation and percutaneous drainage were performed for abdominal infection and pelvic hemorrhage. An obsolete encapsulated effusion that may require treatment in the future was left in the abdominal cavity of a patient (Case 1).

The possibility of controlling abdominal hemorrhage after bariatric/metabolic surgery by conservative treatment is high. When hemorrhage occurs, abdominal drainage can reduce the probability of reoperation by reducing the formation of blood clots behind the stomach.

Core tip: Abdominal drainage allows for timely detection of hemorrhage, but it cannot prevent it. Whether routine abdominal drainage is needed during bariatric procedures remains controversial. The possibility of controlling abdominal hemorrhage after bariatric/metabolic surgery by conservative treatment is high. When hemorrhage occurs, abdominal drainage can reduce the probability of reoperation by reducing the formation of blood clots around the stomach.

- Citation: Liu Y, Li MY, Zhang ZT. Role of abdominal drainage in bariatric surgery: Report of six cases. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(16): 2336-2340

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i16/2336.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2336

The prevalence of morbid obesity is increasing worldwide, and the number of bariatric surgery procedures is accordingly increasing each year[1]. As in other abdominal surgeries, hemorrhage is a challenging issue for bariatric surgeons. Abdominal drainage allows for timely detection of hemorrhage, but it cannot prevent hemorrhage. Whether routine abdominal drainage is needed during bariatric procedures remains controversial[2]. Few reports describe the role of abdominal drainage in the diagnosis and treatment of abdominal hemorrhage in bariatric surgery. We herein present six cases of abdominal hemorrhage in bariatric procedures performed in our center.

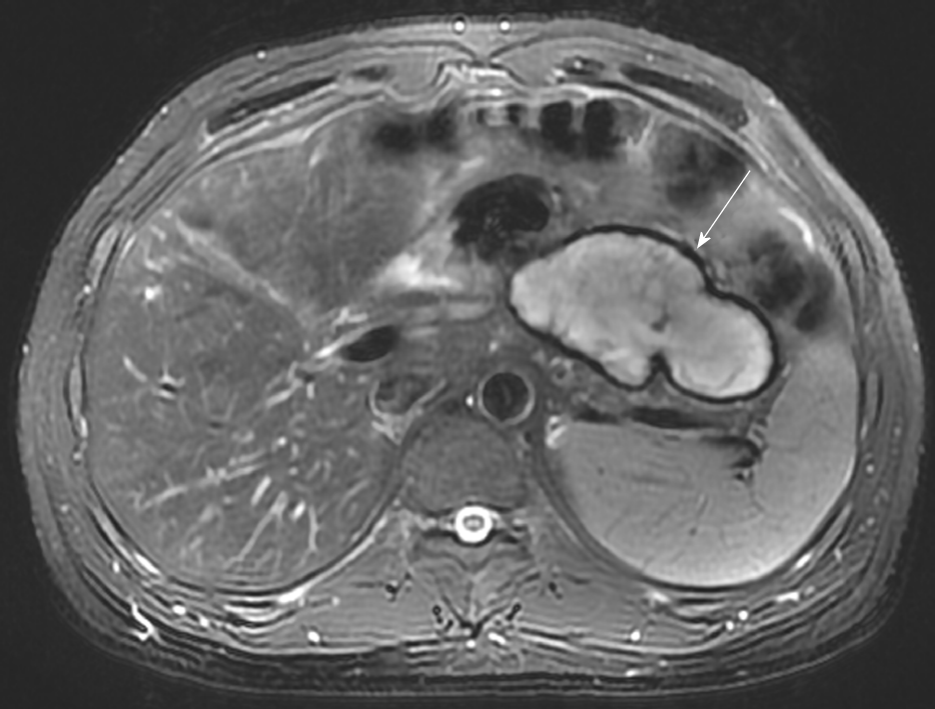

A 37-year-old man with a body mass index (BMI) of 33.73 kg/m2 underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) with cholecystectomy due to chole-cystolithiasis. Abdominal hemorrhage was found on the first postoperative day, and the patient exhibited an accelerated heart rate of 100 to 120 beats per minute (bpm) compared with the preoperative baseline of 60 to 70 bpm. His blood pressure and urine volume remained steady, and conservative treatment was implemented (bed rest, hemostasis, and fluid infusion). The patient’s condition stabilized on postoperative day 4. His hemoglobin level decreased from 15.7 g/dL to 8.0 g/dL, and transfusion of 8 U of red blood cells was therefore performed. On postoperative day 8, 800 mL of blood was percutaneously drained from a pelvic hematocele that had formed. The patient did not require a reoperation and was discharged on postoperative day 10. However, an encapsulated effusion was found in his abdominal cavity by abdominal magnetic resonance imaging at the 3-mo follow-up (Figure 1). Because he had no symptoms, conservative observation was still recommended.

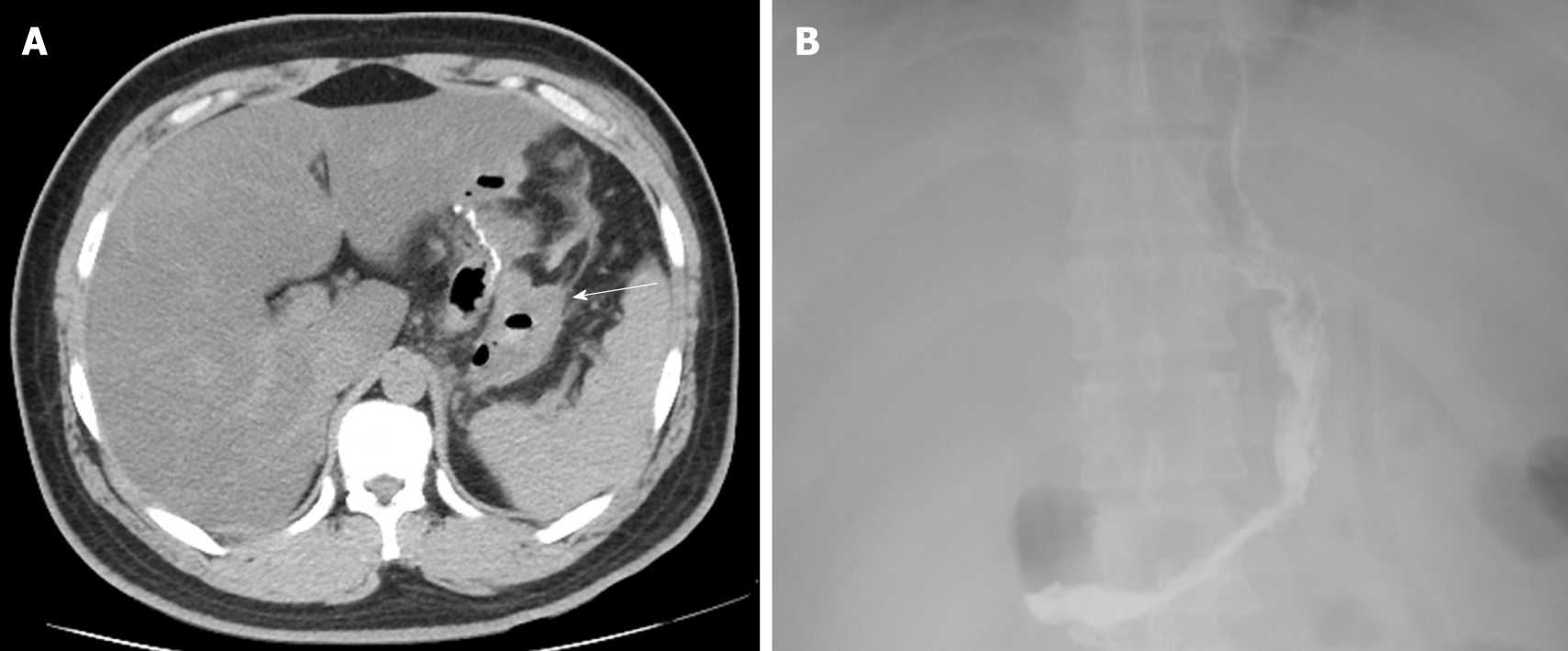

A 32-year-old man with a BMI of 33.46 kg/m2 underwent LSG. Hemorrhage was found on the first postoperative day by routine blood tests and bedside ultrasound examinations. After 48 h of conservative treatment, his condition stabilized and his hemoglobin level decreased by 4.1 g/dL without a blood transfusion. However, he developed a fever of 39 ºC on postoperative day 4. Physical examination revealed tenderness in the epigastrium without guarding or rebound. Antibiotics were administered and 200 mL of blood was percutaneously drained from a pelvic hematocele that had formed; however, the fever did not improve. Abdominal ultrasound findings were normal, but a computed tomography scan showed free air in the peritoneal cavity (Figure 2A). Considering the patient’s increasing generalized abdominal pain and fever, a reoperation was performed on postoperative day 6 to place a drainage tube and confirm whether gastric leakage was present. A large number of blood clots were found in the greater curvature of the stomach during the operation, but neither the location of the abdominal hemorrhage nor the presence of gastric leakage was found. The blood clots were thoroughly cleared and an abdominal drainage tube was placed on the greater curvature side of the stomach. The patient’s recovery was quite rapid after the second operation. On postoperative day 3, after the second surgery, no gastric leakage was detected by upper gastrointestinal radiography (Figure 2B), and oral liquid feeding was started. On day 10, the drainage tube was removed and the patient was discharged with no other complications.

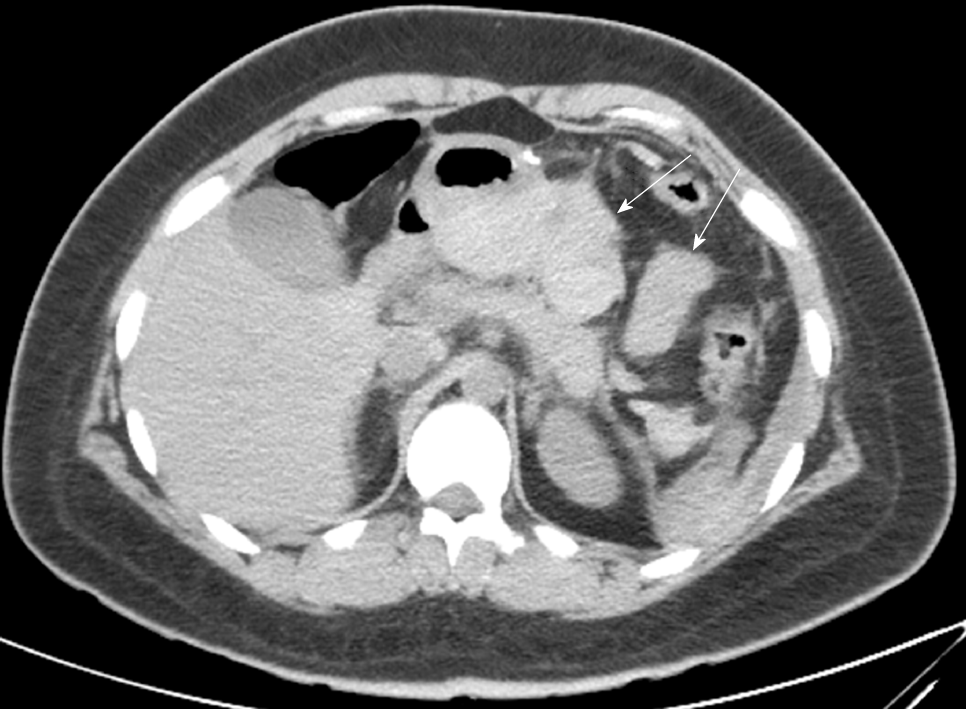

A 20-year-old woman with a BMI of 35.7 kg/m2 underwent LSG. Hemorrhage was found on the first postoperative day by routine blood tests and bedside ultrasound examinations. After 12 h of conservative treatment, the patient’s vital signs remained unstable and her hemoglobin level declined from 14.1 to 7.9 g/dL. A computed tomography scan showed a large number of blood clots behind the stomach (Figure 3), which was a difficult area to drain percutaneously. A reoperation was performed for hemostasis and placement of a drainage tube. The location of hemorrhage was not found by laparoscopy. The blood clots were thoroughly cleared, and an abdominal drainage tube was placed on the greater curvature side of the stomach. During the second postoperative period, the patient’s recovery was quite rapid. On postoperative day 2, oral liquid feeding was started. On day 7, the drains were removed and the patient was discharged with no other complications.

A 47-year-old man with a BMI of 32.8 kg/m2 underwent laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB).

A 42-year-old man with a BMI of 30.2 kg/m2 underwent LRYGB.

A 32-year-old woman with a BMI of 30.9 kg/m2 underwent laparoscopic single anastomosis gastric bypass.

In all of the last three cases, abdominal drainage was performed during the first surgery. Abdominal hemorrhage was found through the drainage tube on the day of the operation. The patients’ heart rate, blood pressure, and urine volume remained steady, and conservative treatment was implemented (bed rest, hemostasis, and fluid infusion). The hemorrhage stopped after the hemoglobin level decreased to 4.4, 3.1, and 6.1 g/dL, respectively, within 48 h. The amount of hemorrhage from the drainage tube was 480, 910, and 750 mL, respectively. In Case 4, 370 mL of blood was percutaneously drained from a pelvic hematocele that had formed. No patients required a reoperation, and no abdominal infection developed.

According to previous reports, the probability of abdominal hemorrhage after bariatric surgery ranges from 1.5% to 2.0%[3]. In total, 343 metabolic procedures have been performed in our center this year, among which six cases of hemorrhage occurred (incidence of 1.7%). All six cases were treated by an experienced surgeon who had surgical experience with > 400 LSG procedures and > 100 gastric bypass procedures. The gastric staple line is reinforced by sutures in the LSG procedure, but not in the gastric bypass procedure. A review of the operative videos showed that the surgical process was relatively smooth in all six cases. The origin of hemorrhage was most likely to be the omental margin in the LSG procedure and the gastric staple line in the gastric bypass procedure.

The concept of enhanced recovery after surgery has gradually gained popularity in recent years[4,5]. Day-case bariatric surgery has been adopted in some bariatric and metabolic centers[6]. Chang et al[7] suggested that omission of drainage may contribute to a shorter time to flatus passage. Doumouras et al[8] suggested that the use of routine abdominal drainage should be restricted to very select, high-risk cases. Drains can increase postoperative pain, lengthen the hospital stay, increase morbidity, and result in a marked peritoneal inflammatory response[9,10]. The concept of no routine abdominal drainage is being advocated by increasingly more surgeons.

The hemorrhage in five of the six cases was controlled by conservative treatment (success rate of 83.3%). Abdominal hemorrhage was found through the drainage tube on the day of the operation in the three patients with abdominal drainage during the first surgery. Emergency treatment was initiated, and their conditions gradually stabilized within 48 h. No patients required a reoperation. Abdominal hemorrhage was found later in the patients without abdominal drainage. Although the hemorrhage was controlled by conservative treatment in Cases 1 and 2, reoperation and percutaneous drainage were performed for abdominal infection and pelvic hemorrhage. An obsolete encapsulated effusion that may require treatment in the future was left in the abdominal cavity of a patient (Case 1). The clinical outcomes of the six cases varied greatly depending on whether abdominal drainage was implemented. Therefore, we believe that it should be in a very prudent way to popularize no routine drainage in bariatric surgery. Hemorrhage cannot be prevented by abdominal drainage, but it can be detected in a timely manner, allowing for immediate implementation of the necessary treatment. When hemorrhage occurs, the greater clinical significance of drainage is to drain the hematocele and reduce the formation of blood clots behind the stomach; such clots developed in the three cases without abdominal drainage in the present study. Blood clots are a likely reason for reoperation because they may lead to the development of infections and are difficult to drain out by other drainage methods.

However, controlled studies with a larger sample size are needed to evaluate the significance of drainage in bariatric/metabolic surgery more objectively.

The possibility of controlling abdominal hemorrhage after bariatric/metabolic surgery by conservative treatment is high. When hemorrhage occurs, abdominal drainage can reduce the probability of reoperation by reducing the formation of blood clots behind the stomach; such clots may lead to the development of infections or persistent residue in the abdominal cavity.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Letitia Adela Maria Streba LAM S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, Vitiello A, Higa K, Himpens J, Buchwald H, Scopinaro N. IFSO Worldwide Survey 2016: Primary, Endoluminal, and Revisional Procedures. Obes Surg. 2018;28:3783-3794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 791] [Cited by in RCA: 725] [Article Influence: 103.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liscia G, Scaringi S, Facchiano E, Quartararo G, Lucchese M. The role of drainage after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:171-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zafar SN, Miller K, Felton J, Wise ES, Kligman M. Postoperative bleeding after laparoscopic Roux en Y gastric bypass: predictors and consequences. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:272-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Blanchet MC, Gignoux B, Matussière Y, Vulliez A, Lanz T, Monier F, Frering V. Experience with an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Program for Bariatric Surgery: Comparison of MGB and LSG in 374 Patients. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1896-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Małczak P, Pisarska M, Piotr M, Wysocki M, Budzyński A, Pędziwiatr M. Enhanced Recovery after Bariatric Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes Surg. 2017;27:226-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rebibo L, Dhahri A, Badaoui R, Dupont H, Regimbeau JM. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as day-case surgery (without overnight hospitalization). Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:335-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chang CC, Lee WJ, Ser KH, Lee YC, Chen SC, Tsou JJ, Chen JC. Routine drainage is not necessary after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2011;4:63-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Doumouras AG, Maeda A, Jackson TD. The role of routine abdominal drainage after bariatric surgery: a metabolic and bariatric surgery accreditation and quality improvement program study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1997-2003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Behrman SW, Zarzaur BL, Parmar A, Riall TS, Hall BL, Pitt HA. Routine drainage of the operative bed following elective distal pancreatectomy does not reduce the occurrence of complications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:72-9; discussion 79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Salgado W, Cunha Fde Q, dos Santos JS, Nonino-Borges CB, Sankarankutty AK, de Castro e Silva O, Ceneviva R. Routine abdominal drains after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a prospective evaluation of the inflammatory response. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:648-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |