Published online Aug 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2330

Peer-review started: May 14, 2019

First decision: June 12, 2019

Revised: June 14, 2019

Accepted: June 26, 2019

Article in press: June 27, 2019

Published online: August 26, 2019

Processing time: 107 Days and 20.5 Hours

Mushroom exposure is a global health issue. The manifestations of mushroom poisoning (MP) may vary. Some species have been reported as rhabdomyolytic, hallucinogenic, or gastrointestinal poisons. Critical or even fatal MPs are mostly attributable to Amanita phalloides, with the development of severe liver or renal failure. Myocardial injury and even cases mimicking ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) have been previously reported, while cardiac arrhythmia or cardiac arrest is not commonly seen.

We report a 68-year-old woman with MP who suffered from delirium, seizure, long QT syndrome on electrocardiogram (ECG), severe cardiac arrhythmias of multiple origins, and cardiac arrest. She was intubated and put on blood perfusion. Her kidney and liver functions were intact; creatine kinase-MB was mildly elevated, and then fell within normal range during her hospital stay. We sent the mushrooms she left for translation elongation factor subunit 1α, ribosomal RNA gene sequence, and internal transcribed spacer sequence analyses. There were four kinds of mushrooms identified, two of which were found to be toxic.

This is the first time that we found cardiac toxicity caused by Panaeolus subbalteatus and Conocybe lactea, which were believed to be toxic to the liver, kidney, and brain. We suggest that intensive monitoring and ECG follow-up are essential to diagnose prolonged QT interval and different forms of tachycardia in MP patients, even without the development of severe liver or renal failure. The mechanisms need to be further investigated and clarified based on animal experiments and molecular signal pathways.

Core tip: Critical or even fatal mushroom poisonings are mostly attributable to Amanita phalloides, with severe liver or renal failure developing. Myocardial injury was reported previously while cardiac arrhythmias of multiple origins or cardiac arrest are definitely rarely seen or reported in the literature. Also, this is the first time that we found cardiac toxicity caused by Panaeolus subbalteatus and Conocybe lactea, which were believed to be hepatic, renal, and brain toxic.

- Citation: Li S, Ma QB, Tian C, Ge HX, Liang Y, Guo ZG, Zhang CD, Yao B, Geng JN, Riley F. Cardiac arrhythmias and cardiac arrest related to mushroom poisoning: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(16): 2330-2335

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i16/2330.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2330

Mycetism, widely known as mushroom poisoning (MP), is an international health care issue. Some species of mushroom are edible or even medicinal and have been proven to have antioxidative effects. Nonetheless, some species initially classified as edible were later recognized as toxic. In general, the majority of MPs are the result of misidentification while attempting to collect wild mushrooms. More unusual intentional ingestion of hallucinogenic species can occur with recreational use. The clinical manifestations of MP may vary. Fatal poisonings are mostly attributable to Amanita phalloides, causing liver and renal failure, while cardiac arrhythmia is not commonly seen.

Here, we present a case of MP in which the patient suffered from severe cardiac arrhythmias and cardiac arrest but was then totally cured at our hospital.

A 68-year-old female patient presented to the emergency department (ED) complaining of dizziness, visual changes, and slight hearing loss.

She had picked mushrooms 2 d ago at a roadside lawn in the community in which she lived in central Beijing. She ate cooked mushrooms for lunch 2 h prior to her admission and reported nausea, dizziness, visual and hearing changes as well as thirst 30 min after ingestion without any other symptoms.

She had a 10-year history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia, taking candesartan 4 mg per day and atorvastatin 10 mg per day. She denied having taken any other prescribed or over-the-counter medications, alcohol, or illegal drugs.

Her vital signs upon arrival were as follows: Blood pressure 194/106 mmHg, heart rate 93 beats per minute, respiratory rate 12 times per minute, body temperature 37 °C, and oxygen saturation 100% on room air. On examination in the ED, she was awake, alert, and oriented. However, she claimed to be thirsty and kept asking “Am I dying?” with a euphoric smile. Her pupils were slightly dilated, with a diameter of 5 mm on both sides. Other than that, her physical examination was negative.

Her ED laboratory tests showed normal complete blood count and chemistry panel with sodium 142.5 mmol/L; potassium 3.78 mmol/L; magnesium 0.9 mmol/L; and normal liver, renal, and coagulative functions as well as myocardial injury markers. Her electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed sinus rhythm with a normal QT interval.

The initial management included immediate fluid resuscitation and oral gastric lavage given the assumed diagnosis of MP, and an intravenous infusion of urapidil was started for blood pressure control. Her blood pressure was 157/96 mmHg after 5 h. A blood sample was sent to the laboratory for further poison screening. However, food residue could be easily seen in her vomitus, and she began to refuse treatment and entered a stage of confusion and then intensive agitation. Therefore, a nasogastric tube was placed for the prevention of aspiration.

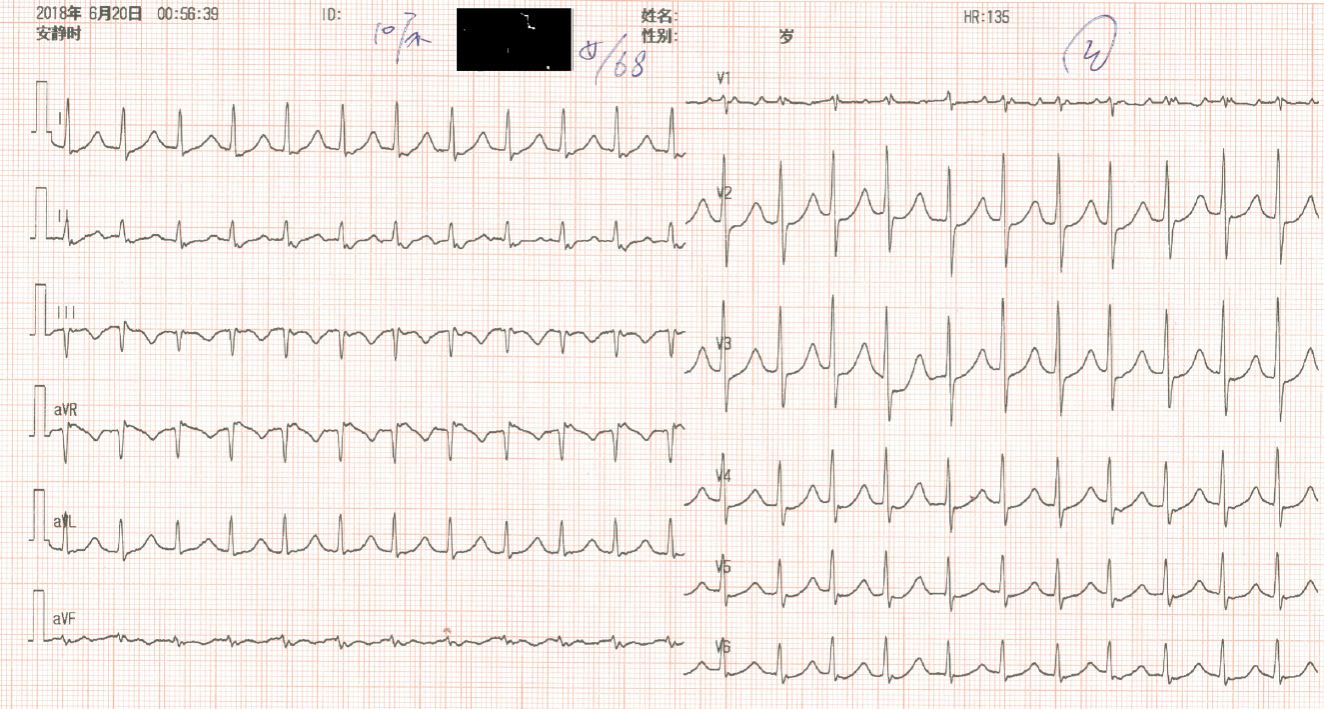

Later, her heart rate gradually increased to approximately 120 beats per minute, and intermittent atrial arrhythmia began, which persisted for several minutes with every episode recovering spontaneously. It was quite unexpected that a seizure suddenly developed without arrhythmia onset. It lasted for approximately 1 min, and after termination of the seizure, she immediately had pulseless ventricular tachycardia and cardiac arrest. Fortunately, she had a return of spontaneous circulation after 2 min of CPR and 1 mg epinephrine administration. She was intubated because of vomiting, prior seizure, the need for sedation, and the probability of recurrent cardiac arrest based on her unstable status. No secretions were found during intubation, and her brain CT scan showed no intracranial bleeding or ischemia. The post-cardiac arrest ECG revealed a prolonged QT interval (QT interval 360 msec when heart rate was 135 beats per minute and corrected QT interval was 540 ms, Figure 1). We put her on blood perfusion for 2 days. She was extubated, totally conscious and had no recurrence of seizure. The toxicity screen, thyroid function, and brain MR were all negative. Her creatine kinase (CK) and kinase-MB (CKMB) were elevated mildly (37 U/L and 245 U/L, respectively) and trended to the normal range after fluid resuscitation. The QT interval also returned to normal. Troponin I (TNI) was negative on serial tests during the hospital stay. She underwent uneventful hospital stay and was discharged 7 days after admission.

We sent the mushroom she left for translation elongation factor subunit 1α, ribosomal RNA gene sequence, and internal transcribed spacer sequence analyses. There were four kinds of mushrooms identified, including Hebeloma sp., Psathyrella leucotephra, Panaeolus subbalteatus, and Conocybe lactea. The latter two were found to be toxic (Figure 2A and B, respectively).

There are 100000 known species of fungi worldwide. Approximately 100 of the known species of mushrooms are poisonous to humans. The incidence of MP varies a great deal with respect to the global perspective. The mortality rate reported was 10–15%, or even as high as 21.2%. The prognosis of patients varies greatly and is affected by many factors, including the type of mushroom, intake amount, ED visit time, and treatment strategy. According to the incubation period, the stages of MP are separated into early (< 6 h), delayed (6–24 h), and late (> 24 h). There is a great diversity of clinical manifestations, which are generally divided into different subtypes such as gastrointestinal, hepatic, nephrological, neuropsychiatric, hemolytic, and photoallergic, depending on the type of mushroom ingested and the toxin contained.

Panaeolus subbalteatus, also having been named Panaeolus cinctulus in the past, is commonly known as “Weed Panaeolus”. It is a very widely distributed psilocybin mushroom that causes hallucination[1]. The dramatic effects are caused by fungi holding neurotoxins, such as muscarine (Clitocybe and Inocybe spp.) and psilocybin (Psilocybe and Panaeolus spp.). Psilocybin and related substances are potent hallucinogens producing effects similar to those of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Psilocybin and/or psilocin have also been detected in Conocybe lactea, named Conocybe apala or the White Dunce Cap, which was the other kind of mushroom involved in this case. They can both be found in areas with rich soil and short grass, such as pastures, playing fields, lawns, road sides, and meadows, as well as rotting manured straw or rotting vegetable remains. These “magic” mushrooms, also called “dancing mushrooms” or “laughing mushrooms” in China, are usually ingested intentionally for their hallucinogenic effects in developed countries or ingested accidentally due to being mistaken for other edible species. Symptoms occur within 20–60 min after ingestion and include a sense of altered time and space, euphoria, depersonalization, hallucinations, anxiety, agitation, mydriasis, vertigo, headache, nausea, enlarged pupils, tachycardia, flushing, fever, and seizures. Symptoms are usually maximal within 2 h and disappear within 4–6 h, although “flashback” may recur after weeks or months[2]. Our patient had an early onset (< 6 h) of symptoms and was conscious with hearing and sight alterations upon arrival. Then, she underwent a period of euphoria, hallucination, agitation, and seizure, which were all well explained by the toxicity of psilocybin.

As known to all, the consumption of wild mushrooms may cause serious toxicity to hepatic, renal, and neurological functions. Conocybe lactea can also be highly toxic to liver cells, containing phallotoxins which are famous as isolated from the death cap mushroom (Amanita phalloides)[3]. However, the toxic effects of MP on the cardiovascular system have been rarely investigated or reviewed systemically, and the conclusions have been controversial.

Elevated CKMB and TNI, ventricular dysfunction, and cardiogenic shock were reported in a few previous studies. All of the probable pathological mechanisms were previously based on speculation from the well-known species, Amanita phalloides, which has the toxicity of amatoxins, circulating antitroponin antibodies that impair myocardiocytes. Kalclk published a clinical case of a 25-year-old woman who presented with severe crushing chest pain after consumption of wild mushrooms. The ECG showed ST segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF. Acute myocardial infarction was confirmed with profoundly elevated CKMB and TNI. Cardioangiography showed normal coronary arteries. It was thought that myocardial infarction was secondary to coronary spasm. A potential mechanism might be vasoconstrictive substances emerging as a result of endothelial damage by the toxins[4]. Furthermore, Krzysztof once reported that the patients’ serum and urine indole alkaloids, which are agonists of the 5-HT receptors and may lead to coronary vasoconstriction, were strongly positive[5]. Later, on the other hand, Erenler reviewed 175 patients with MP over a 2-year period, and the cardiac markers of the patients were found to be normal[6].

Moreover, Erenler concluded that MP causes hypertension and ECG alterations in his article. Sinus tachycardia and sinus arrhythmia were the most common types of arrhythmia found in patients with MP. The prevalence of tachycardia was significantly higher in patients with late-onset symptoms (> 6 h). Furthermore, the blood pressure of the patients tended to increase as the interval between mushroom consumption and onset of symptoms prolonged. Other ECG manifestations included ST/T inversion, first degree AV block, and QT prolongation[6]. Another case was described in an 18-year-old man who developed Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, myocardial infarction, and cardiac arrest[5]. Considering the life-threatening features of MP, Graeme reviewed the symptoms of palpitation, chest discomfort, dizziness, recurrent syncope, and seizure, followed by sudden death, in patients linked to mushroom ingestions. Ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation may precede death[7]. The mechanisms of cardiovascular damage were suggested to be related to peripheral sympathomimetic stimulation by psilocybin, which were contained in both of the toxic species of mushrooms we have identified here[5]. Unfortunately, almost none of the authors succeeded in the identification of the species of mushroom that causes unusual cardiovascular toxicity.

Our patient experienced several types of arrhythmia, including sinus tachycardia, atrial arrhythmia, ventricular tachycardia, prolonged QT interval, and cardiac arrest. Fortunately, she had a return of spontaneous circulation, and her CKMB was mildly elevated without cardiogenic shock or ventricular failure. She did not have severe liver or renal damage, except for periodic psychotic manifestations. All of her symptoms disappeared after hemoperfusion treatment. This is the first time that we found cardiac toxicity caused by Panaeolus subbalteatus and Conocybe zeylanica.

MP can be critical or fatal, even without the development of severe liver or renal failure. The patient may have sinus, atrial, or ventricular arrhythmias. Intensive monitoring and ECG follow-up are essential to catch prolonged QT interval and all kinds of tachycardia. The mechanisms need to be further investigated and clarified based on animal experiments and molecular signal pathways. Blood perfusion or hemodialysis is usually an effective treatment for severe MP.

Special thanks to Dr. Fran Riley. We worked on the manuscript together to celebrate our reunion after 27 years on the other side of the planet both working as ED doctors.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Erkut B S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Watling R. A panaeolus poisoning in Scotland. Mycopathologia. 1977;61:186-190. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Amandeep K, Atri NS and Munruchi K. Diversity of species of the genus Conocybe(Bolbitiaceae, Agaricales) collected on dung from Punjab, India. Mycosphere. 2015;6:19-42. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kalcik M, Gursoy MO, Yesin M, Ocal L, Eren H, Karakoyun S, Astarcıoğlu MA, Özkan M. Coronary vasospasm causing acute myocardial infarction: an unusual result of wild mushroom poisoning. Herz. 2015;40:340-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Borowiak KS, Ciechanowski K, Waloszczyk P. Psilocybin mushroom (Psilocybe semilanceata) intoxication with myocardial infarction. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1998;36:47-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Erenler AK, Doğan T, Koçak C, Ece Y. Investigation of Toxic Effects of Mushroom Poisoning on the Cardiovascular System. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;119:317-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Graeme KA. Mycetism: a review of the recent literature. J Med Toxicol. 2014;10:173-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |