Published online Aug 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2287

Peer-review started: March 15, 2019

First decision: June 19, 2019

Revised: June 25, 2019

Accepted: July 20, 2019

Article in press: July 20, 2019

Published online: August 26, 2019

Processing time: 166 Days and 12 Hours

Perioperative shivering is clinically common during cesarean sections under neuraxial anesthesia, and several neuraxial adjuvants are reported to have preventive effects on it. However, the results of current studies are controversial and the effects of these neuraxial adjuvants remain unclear.

To evaluate the effects of neuraxial adjuvants on perioperative shivering during cesarean sections, thus providing an optimal choice for clinical application.

A systematic review and network meta-analysis were conducted following the PRISMA (Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis) guidelines. Analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.3 and Stata 14.0. We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Central databases for eligible clinical trials assessing the effects of neuraxial adjuvants on perioperative shivering and other adverse events during cesarean sections. Perioperative shivering was defined as the primary endpoint, and nausea, vomiting, pruritus, hypotension, and bradycardia were the secondary outcomes.

Twenty-six studies using 9 neuraxial adjuvants for obstetric anesthesia during caesarean sections were included. The results showed that, compared with placebo, pethidine, fentanyl, dexmedetomidine, and sufentanil significantly reduced the incidence of perioperative shivering. Among the four neuraxial adjuvants, pethidine was the most effective one for shivering prevention (OR = 0.15, 95%CI: 0.07-0.35, surface under the cumulative ranking curve 83.9), but with a high incidence of nausea (OR = 3.15, 95%CI: 1.04-9.57) and vomiting (OR = 3.71, 95%CI: 1.81-7.58). The efficacy of fentanyl for shivering prevention was slightly inferior to pethidine (OR = 0.20, 95%CI: 0.09-0.43), however, it significantly decreased the incidence of nausea (OR = 0.34, 95%CI: 0.15-0.79) and vomiting (OR = 0.25, 95%CI: 0.11-0.56). In addition, compared with sufentanil, fentanyl showed no impact on haemodynamic stability and the incidence of pruritus.

Pethidine, fentanyl, dexmedetomidine, and sufentanil appear to be effective for preventing perioperative shivering in puerperae undergoing cesarean sections. Considering the risk-benefit profiles of the included neuraxial adjuvants, fentanyl is probably the optimal choice.

Core tip: Shivering is a common complication of obstetric anaesthesia, especially during caesarean section. Recently, several neuraxial adjuvants have been used for the prevention of shivering. However, the results of current studies are controversial and the role of these adjuvants in obstetric anesthesia remains unclear. The aim of our network meta-analysis is to evaluate the effects of neuraxial adjuvants on shivering and other side effects, thus providing an optimal choice for clinical application.

- Citation: Zhang YW, Zhang J, Hu JQ, Wen CL, Dai SY, Yang DF, Li LF, Wu QB. Neuraxial adjuvants for prevention of perioperative shivering during cesarean section: A network meta-analysis following the PRISMA guidelines. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(16): 2287-2301

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i16/2287.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2287

There are about 18.5 million cesarean deliveries performed each year worldwide[1]. Neuraxial anaesthesia is the commonest technique for obstetric anesthesia because it is easy to handle, underspent, and of less adverse effects or complications[2]. Perioperative shivering is very common during caesarean section under neuraxial anaesthesia, with an incidence of 29%-54%[3], which increases catecholamine excretion, maternal metabolic rate, carbon dioxide production, and oxygen consumption, thereby interfering with the operation and anesthesia monitoring[4,5]. In clinical practice, several neuraxial drugs have been used as adjuvants to local anaesthetics for obstetric anesthesia[6,7], and some of them have been found to alleviate the side effects, including shivering[8,9], but the results of these studies are still controversial, because there are also a few studies showing that some neuraxial adjuvants did not reduce the incidence of the side effects during cesarean section[6,10]. Furthermore, so far, there are no relevant guidelines or standards available for clinical practice, and it remains to identify the most preferable neuraxial adjuvant for shivering prevention in the puerperae undergoing cesarean sections.

In the present analysis, we performed a network meta-analysis (NMA) to comprehensively compare the effects of several neuraxial adjuvants on shivering and other adverse reactions during caesarean section, with an aim to help guide clinicians in making optimal preventive regimen for puerperae undergoing cesarean sections.

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted following the Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

We searched for available clinical trials in PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Central databases that published by August 7, 2018. The retrieval was not restricted by age, data, or language. The combinations of our search terms were (“shivering” or “chill” or “chillness”) AND (“lumbar anaesthesia” or “subarachnoid anaesthesia” or “regional anaesthesia” or “intrathecal anaesthesia” or “neuraxial anaesthesia” or “spinal anesthesia” or “peridural anesthesia” or “extradural anesthesia” or “epidural anesthesia”) AND (“caesarean” or “caesarean” or “c-section”).

Studies included in this study should meet the following criteria: (1) Surgery type: Caesarean section; (2) Anesthesia type: Spinal anesthesia (SA), epidural anesthesia (EA), or combined spinal-epidural anesthesia (CSEA); (3) Administration time: During the anesthesia; (4) Administration method: intrathecal or extradural; and (5) Original and prospective clinical trials.

Types of interventions were: Local anesthetics plus neuraxial adjuvant in the experimental group; local anesthetics plus placebo in the control group. All kinds of local anesthetics and neuraxial adjuvants were eligible.

We excluded descriptive literature reviews or systemic reviews, case reports, and studies that were unable to extract any data by reviewing titles, abstracts, and full papers. All the included studies met the inclusion criteria.

Our primary outcome was the incidence of shivering during and after caesarean section. Most studies graded shivering with a scale described by Crossley and Mahajan: 0: No shivering; 1: Piloerection or peripheral vasoconstriction but no visible shivering; 2: Muscular activity in only one muscle group; 3: Muscular activity in more than one muscle group but not generalized shivering; and 4: Shivering involving the whole body[11]. So we incorporated data only when the grade of shivering was greater than or equal to the grade 2.

The secondary outcomes were the incidence of other adverse reactions including: (1) Nausea; (2) Vomiting; (3) Pruritus; (4) Hypotension; and (5) Bradycardia. Postoperative nausea and vomiting were reported in a few eligible studies, and these data were extracted and pooled to evaluate the corresponding outcomes. Additionally, when the data came with time point, we took the data at the longest time point.

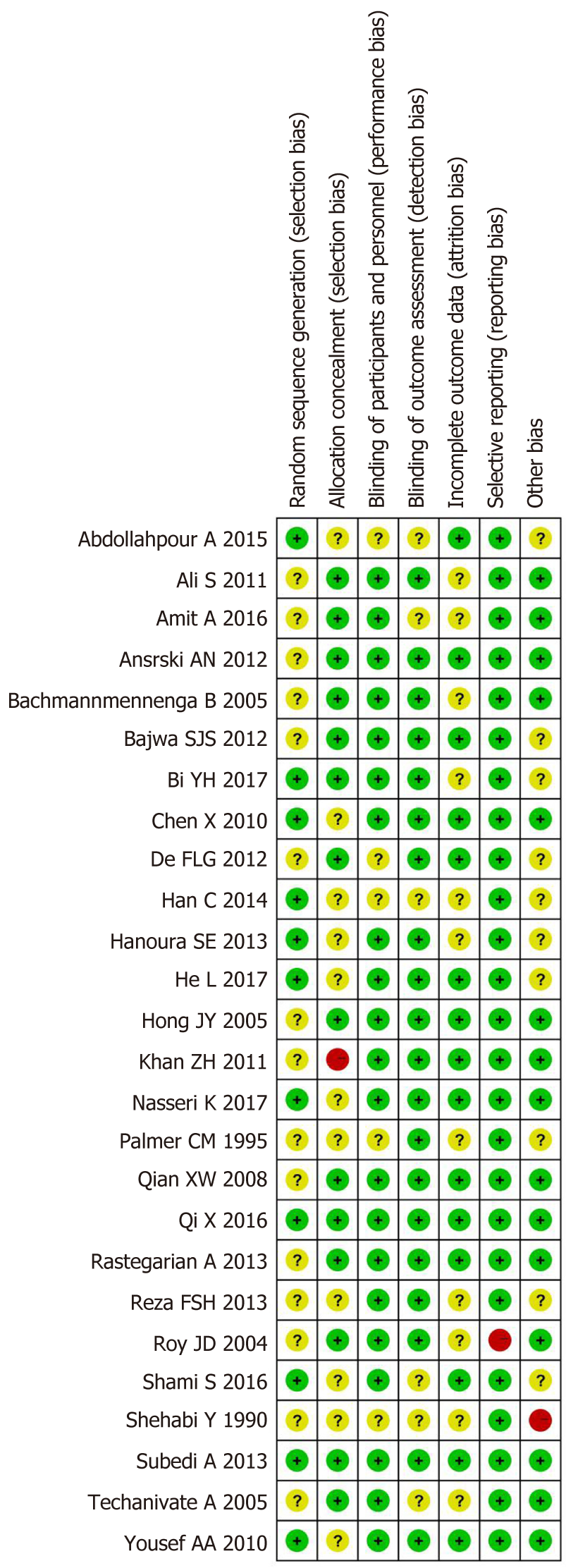

According to our protocol, all of our data were independently extracted and assessed by two investigators using a standard data table, and any disagreements were solved through consultation with the third party. The following contents were extracted from the included studies: first author and publication year, sample size, intraoperative ambient temperature, type of anesthesia, administration method, local anesthetic intervention, and clinical outcomes. We used the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias Tool to assess the risk of bias of eligible studies[12].

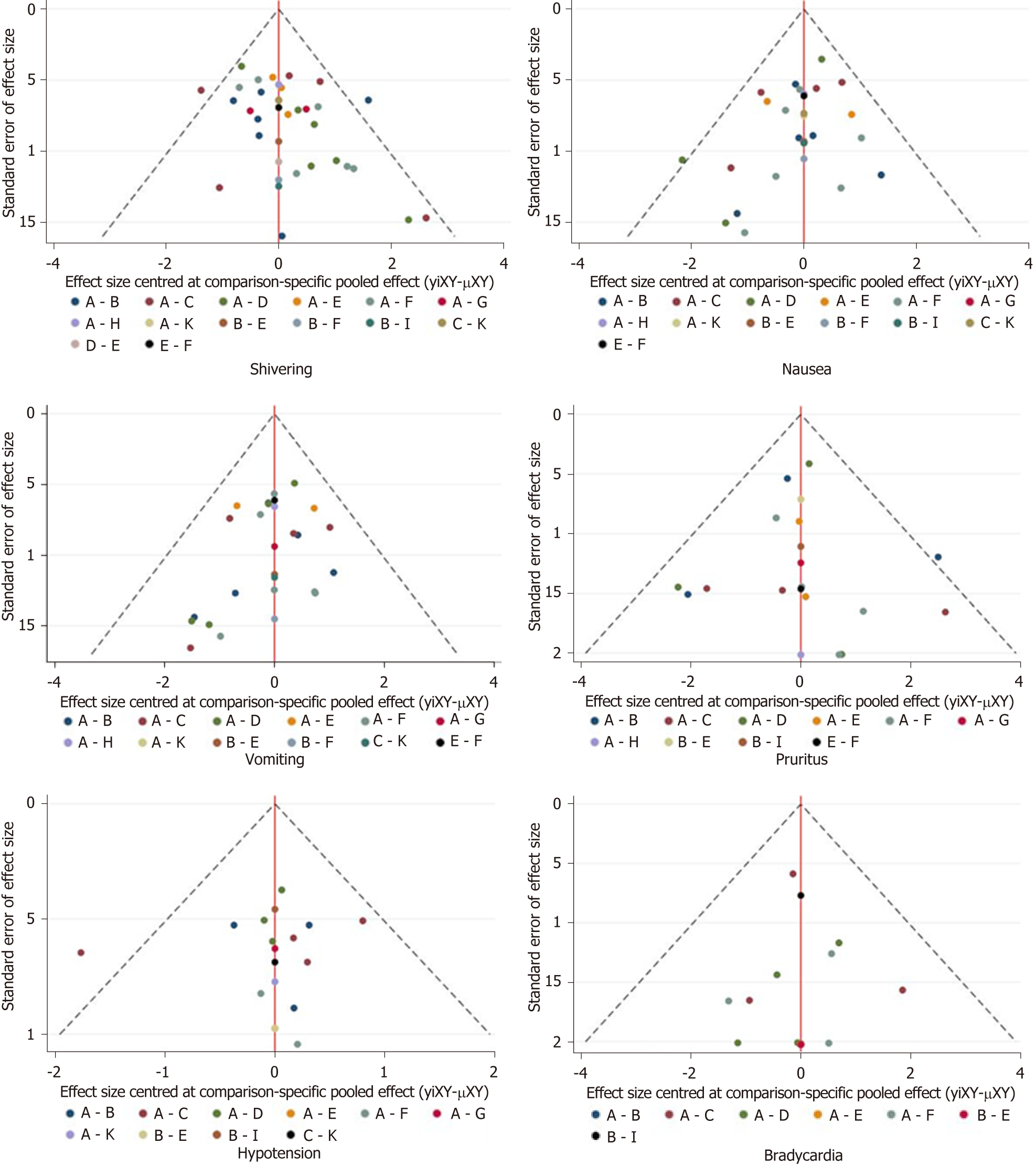

We performed NMA to synthesize evidence using STATA software (version 14.0). Odds ratio (OR) was used to estimate all outcomes. Surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) represented the corresponding ranking of each outcome; the higher the value, the more effective the intervention. After that, the degree of inconsistency was analyzed by the node-splitting method, and the risk of publication bias is shown on funnel plots[13,14].

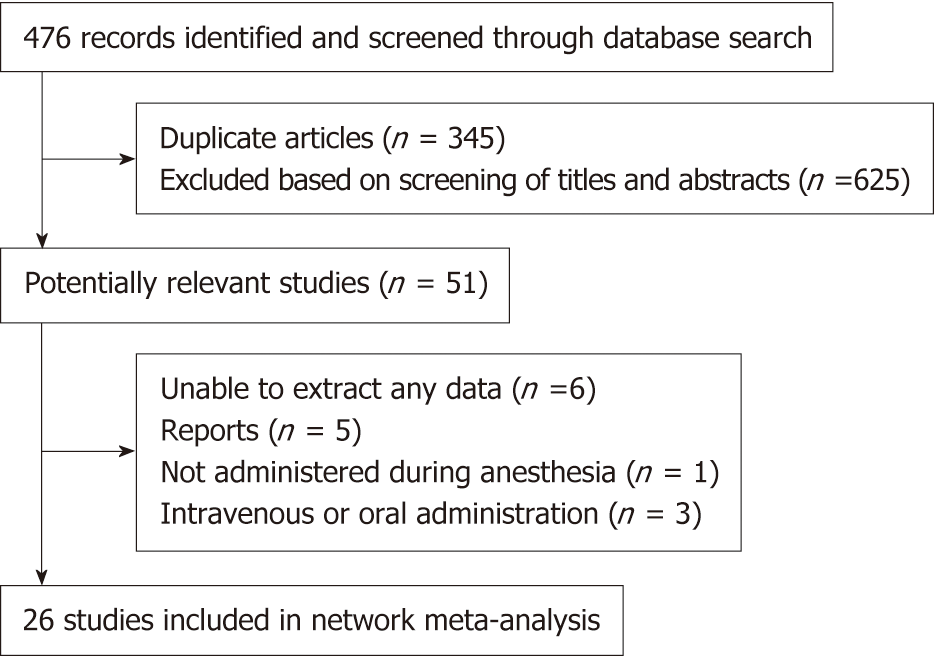

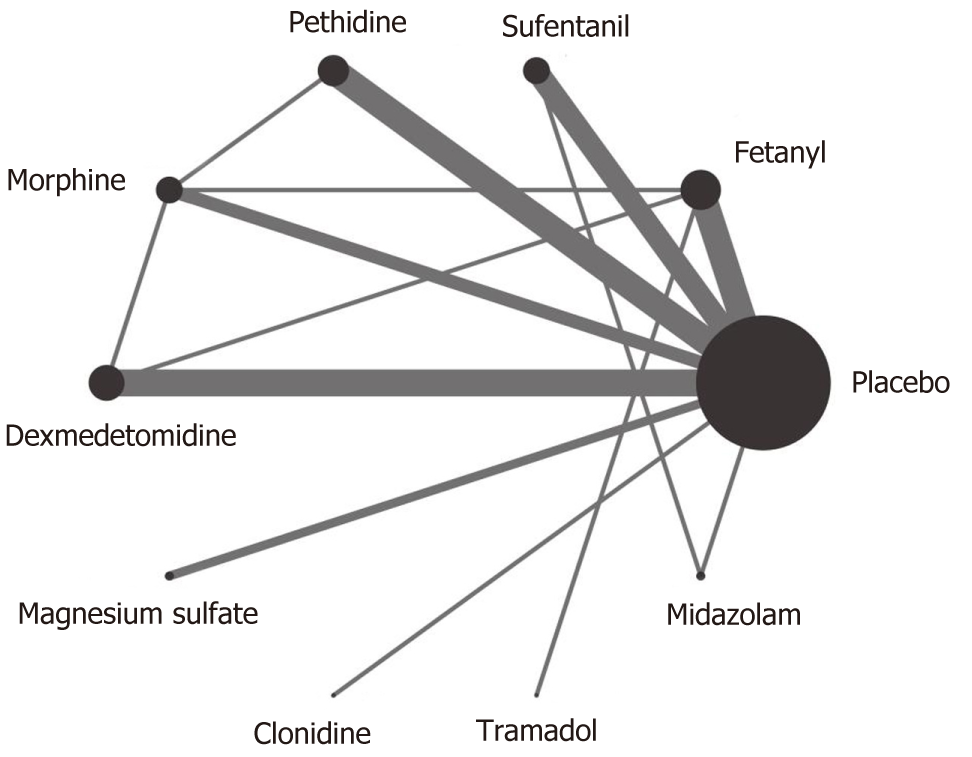

As showed in the flow diagram (Figure 1), 476 records were screened after initial searches in PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. And 51 citations remained after exclusion of duplicate articles by screening title and abstracts. Finally, 26 studies with 2054 puerperae were selected for full text reviews (Figure 1), which were performed in 10 countries from 1990 to 2017[3,6-10,15-34]. The included studies compared the following 9 neuraxial adjuvants with placebo: Fentanyl, sufentanil, pethidine, morphine, dexmedetomidine, magnesium sulfate, clonidine, tramadol, and midazolam. Three types of anesthesia were used in the included studies: SA in 17 studies (65.4%), EA in 3 (11.5%), and CSEA in 6 (23.1%). Three kinds of local anesthetics were used in the studies: bupivacaine (76.9%), ropivacaine (15.4%), and lidocaine (7.7%). The specific concentrations of local anesthetics are presented in Table 1. The network of eligible comparisons of all adjuvants for shivering is showed in Figure 2; 21 studies were two-arm trials and 5 were three-arm trials.

| First author, year | Size | Intraoperative ambient temperature | Type of anesthesia | Administration method | Local anesthetic | Intervention | Outcomes |

| Palmer et al[15], 1995 | 28 | Unclear | SA | Intrathecal | 5% lidocaine | Fentanyl vs Placebo | ③④ |

| Shehabi et al[16], 1990 | 62 | 21 °C | EA | Extradural | 0.5% bupivacaine | Fentanyl vs Placebo | ① |

| Han et al[17], 2014 | 60 | Unclear | EA | Extradural | 0.75% ropivacaine | Fentanyl vs Dexmedetomidine vs Placebo | ③ |

| Shami et al[34], 2016 | 150 | 24-26 °C | CSEA | Intrathecal | 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine | Pethidine vs Placebo | ③④⑤⑥ |

| Techanivate et al[33], 2005 | 60 | 23 °C | SA | Intrathecal | 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine plus 0.2 mg morphine | Fentanyl vs Placebo | ③④⑤⑥ |

| Roy et al[18], 2004 | 40 | 21–23 °C | SA | Intrathecal | 0.75% hyperbaric bupivacaine plus 0.15 mg morphine | Pethidine vs Placebo | ① |

| Qi et al[19], 2016 | 118 | Unclear | SA | Intrathecal | 0.5% bupivacaine | Dexmedetomidine vs Morphine vs Placebo | ③④ |

| Chen et al[31], 2010 | 64 | Unclear | SA | Intrathecal | 0.75% ropivacaine | Sufentanil vs Placebo | ③④⑤⑥ |

| Bachmann-Mennenga et al[21], 2005 | 60 | Unclear | EA | Extradural | 1% ropivacaine | Sufentanil vs Placebo | ③④⑤⑥ |

| Abdollahpour et al[10], 2015 | 75 | Unclear | SA | Intrathecal | 0.5% bupivacaine | Midazolam vs Sufentani vs Placebo | ③⑤ |

| He et al[7], 2017 | 90 | 22–28 °C | SA | Intrathecal | 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine | Dexmedetomidine vs Placebo | ③④⑥ |

| Nasseri et al[22], 2017 | 50 | 22–26 °C | SA | Intrathecal | 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine | Dexmedetomidine vs Placebo | ③⑤⑥ |

| de Figueiredo Locks et al[3], 2012 | 80 | Unclear | SA | Intrathecal | 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine | Sufentanil vs Placebo | ① |

| Rastegarian et al[9], 2013 | 100 | Unclear | SA | Intrathecal | 5% hyperbaric lidocaine | Pethidine vs Placebo | ③④⑤⑥ |

| Khan et al[6], 2011 | 72 | 21–23 °C | SA | Intrathecal | 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine | Pethidine vs Placebo | ③⑤⑥ |

| Hong et al[23], 2005 | 120 | 23–25 °C | CSEA | Intrathecal | 0.5% bupivacaine | Morphine vs Pethidine vs Placebo | ① |

| Agrawal et al[24], 2016 | 60 | Unclear | SA | Intrathecal | 0.3% bupivacaine | Morphine vs Fentanyl vs Placebo | ③④⑤⑥ |

| Hanoura et al[25], 2013 | 50 | Unclear | CSEA | Extradural | 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine (intrathecal) 0.25% bupivacaine plus 100ug fentanyl (extradural) | Dexmedetomidine vs Placebo | ③④⑤⑥ |

| Anaraki et al[26], 2012 | 156 | 21–23°C | SA | Intrathecal | 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine | Pethidine vs Placebo | ③④⑥ |

| Bajwa et al[27], 2012 | 100 | Unclear | SA | Intrathecal | 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine | Clonidine vs Placebo | ③④ |

| Bi et al[28], 2017 | 60 | Unclear | CSEA | Intrathecal | 0.5% bupivacaine | Dexmedetomidine vs Placebo | ③④ |

| Yousef et al[29], 2010 | 90 | Unclear | CSEA | Extradural | 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine (intrathecal) 0.25% bupivacaine plus 100ug fentanyl (extradural) | Magnesium sulfate vs Placebo | ③④⑤ |

| Subedi et al[30], 2013 | 77 | Unclear | SA | Intrathecal | 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine | Tramadol vs Fentanyl | ④⑤⑥ |

| Qian et al[31], 2008 | 80 | Unclear | CSEA | Intrathecal | 0.6% ropivacaine | Sufentanil vs Placebo | ③④⑤⑥ |

| Faiz et al[8], 2013 | 72 | 23–25 °C | SA | Intrathecal | 0.5% bupivacaine | Magnesium sulfate vs Placebo | ① |

| Sadegh et al[32], 2011 | 80 | 24 °C | SA | Intrathecal | 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine | Fentanyl vs Placebo | ①②③⑤ |

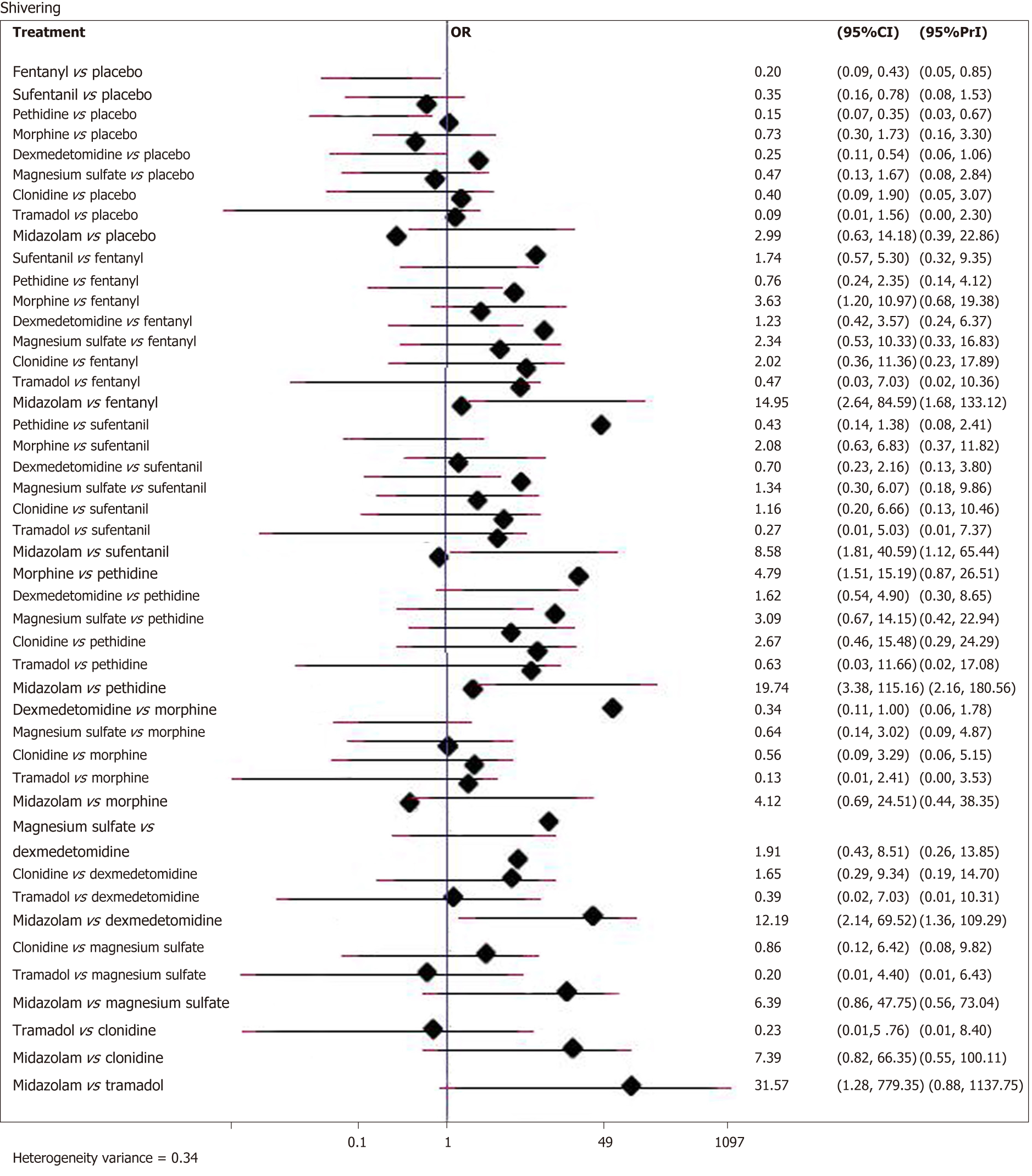

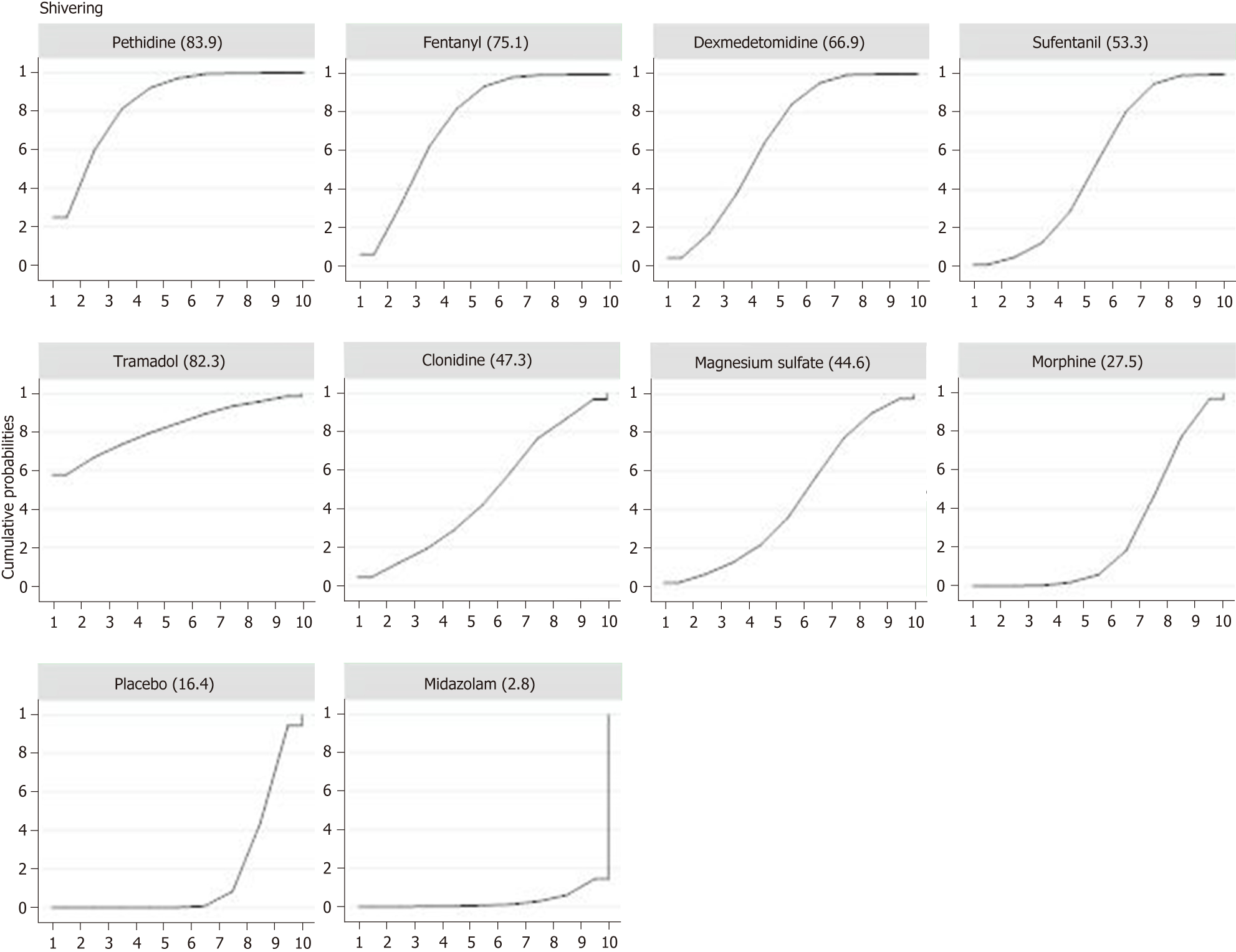

Twenty-six studies with a total of 2054 patients reported data of the incidence of shivering. Compared with placebo, eight adjuvants decreased the incidence of shivering, and four of them demonstrated statistically significant effects (Figure 3) (pethidine vs placebo: OR = 0.15, 95%CI: 0.07-0.35; fentanyl vs placebo: OR = 0.20, 95%CI: 0.09-0.43; dexmedetomidine vs placebo: OR = 0.25, 95%CI: 0.11-0.54; sufentanil vs placebo: OR = 0.35, 95%CI: 0.16-0.78). Besides, as showed in SUCRA curve graph (Figure 4), the four largest SUCRA values were as follows: Pethidine (83.9), fentanyl (75.1), dexmedetomidine (66.9), and sufentanil (53.3).

Overall, fentanyl reduced the incidence of nausea (fentanyl vs placebo: OR = 0.34, 95%CI: 0.15-0.79) and vomiting (fentanyl vs placebo: OR = 0.25, 95%CI: 0.11-0.56) compared with the control groups. On the contrary, patients treated with pethidine showed a higher incidence of nausea (pethidine vs placebo: OR = 3.15, 95%CI: 1.04-9.57) and vomiting (pethidine vs placebo: OR = 3.71, 95%CI: 1.81-7.58). Besides, sufentanil reduced the incidence of vomiting (sufentanil vs placebo: OR = 0.34, 95%CI: 0.14-0.80) and hypotension [sufentanil vs placebo: OR = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.23-0.96). However, the incidence of pruritus increased when sufentanil was used (sufentanil vs placebo: OR = 20.37, 95%CI: 2.44-169.96)]. Differences in the incidence of bradycardia between the intervention and control groups were not statistically significant. A complete summary table with SUCRA values and effect size is displayed in Table 2.

| Nausea (Heterogeneity variance = 0.17) | Vomiting (Heterogeneity variance = 0.00) | ||||||||

| Rank | Treatment | SUCRA | OR | 95%CI | Rank | Treatment | SUCRA | OR | 95%CI |

| 1 | Midazolam | 86.10 | 0.20 | (0.04, 0.96) | 1 | Fentanyl | 79.90 | 0.25 | (0.11, 0.56) |

| 2 | Fentanyl | 77.10 | 0.34 | (0.15, 0.79) | 2 | Sufentanil | 70.70 | 0.34 | (0.14, 0.80) |

| 3 | Pethidine | 4.30 | 3.15 | (1.04, 9.57) | 3 | Pethidine | 1.10 | 3.71 | (1.81, 7.58) |

| 1 | Clonidine | 79.30 | 0.26 | (0.06, 1.10) | 1 | Midazolam | 89.90 | 0.11 | (0.01, 1.00) |

| 2 | Tramadol | 58.50 | 0.51 | (0.06, 4.58) | 2 | Clonidine | 69.30 | 0.35 | (0.10, 1.26) |

| 3 | Magnesium sulfate | 53.00 | 0.65 | (0.09, 4.88) | 3 | Magnesium sulfate | 48.70 | 0.65 | (0.10, 4.10) |

| 4 | Dexmedetomidine | 44.50 | 0.82 | (0.38, 1.76) | 4 | Dexmedetomidine | 38.10 | 0.87 | (0.43, 1.74) |

| 5 | Sufentanil | 37.20 | 0.97 | (0.45, 2.06) | 5 | Placebo | 32.20 | ||

| 6 | Placebo | 34.80 | 6 | Morphine | 20.10 | 1.42 | (0.62, 3.26) | ||

| 7 | Morphine | 25.10 | 1.30 | (0.47, 3.56) | |||||

| Pruritus (heterogeneity variance = 1.18) | Hypotension (heterogeneity variance = 0.15) | ||||||||

| Rank | Treatment | SUCRA | OR | 95%CI | Rank | Treatment | SUCRA | OR | 95%CI |

| 1 | Morphine | 22.60 | 6.54 | (1.02, 41.88) | 1 | Midazolam | 99.70 | 0.04 | (0.01, 0.19) |

| 2 | Sufentanil | 7.40 | 20.37 | (2.44, 169.96) | 2 | Sufentanil | 74.50 | 0.47 | (0.23, 0.96) |

| 1 | Tramadol | 76.90 | 0.40 | (0.01, 12.33) | 1 | Magnesium sulfate | 56.50 | 0.68 | (0.16, 2.87) |

| 2 | Clonidine | 75.90 | 0.34 | (0.00, 29.96) | 2 | Morphine | 55.20 | 0.68 | (0.11,4.42) |

| 3 | Dexmedetomidine | 71.90 | 0.74 | (0.13, 4.17) | 3 | Placebo | 41.20 | ||

| 4 | Placebo | 68.00 | 4 | Dexmedetomidine | 32.50 | 1.22 | (0.31, 4.85) | ||

| 5 | Magnesium sulfate | 48.60 | 2.05 | (0.08, 52.19) | 5 | Pethidine | 31.70 | 1.18 | (0.59, 2.36) |

| 6 | Pethidine | 39.60 | 2.98 | (0.50, 17.73) | 6 | Fentanyl | 31.50 | 1.18 | (0.52, 2.67) |

| 7 | Fentanyl | 39.10 | 2.84 | (0.58, 13.91) | 7 | Tramadol | 27.30 | 1.39 | (0.33, 5.77) |

| Bradycardia (heterogeneity variance = 0.00) | |||||||||

| Rank | Treatment | SUCRA | OR | 95%CI | |||||

| 1 | Pethidine | 82.30 | 0.32 | (0.07, 1.42) | |||||

| 2 | Dexmedetomidine | 52.70 | 0.84 | (0.14, 4.87) | |||||

| 3 | Fentanyl | 49.50 | 1.00 | (0.06, 16.44) | |||||

| 4 | Morphine | 47.70 | 1.00 | (0.02, 40.86) | |||||

| 5 | Placebo | 46.70 | |||||||

| 6 | Sufentanil | 39.10 | 1.21 | (0.44, 3.37) | |||||

| 7 | Tramadol | 32.00 | 1.72 | (0.07, 41.24) | |||||

The risk of bias assessment is presented in Figure 5. Three of the included studies[6,16,18] were rated as high risk of bias due to inappropriate allocation concealment, selective data reporting, and unclear reporting of statistical methods. The asymmetry in the funnel plots indicated publication bias (Figure 6).

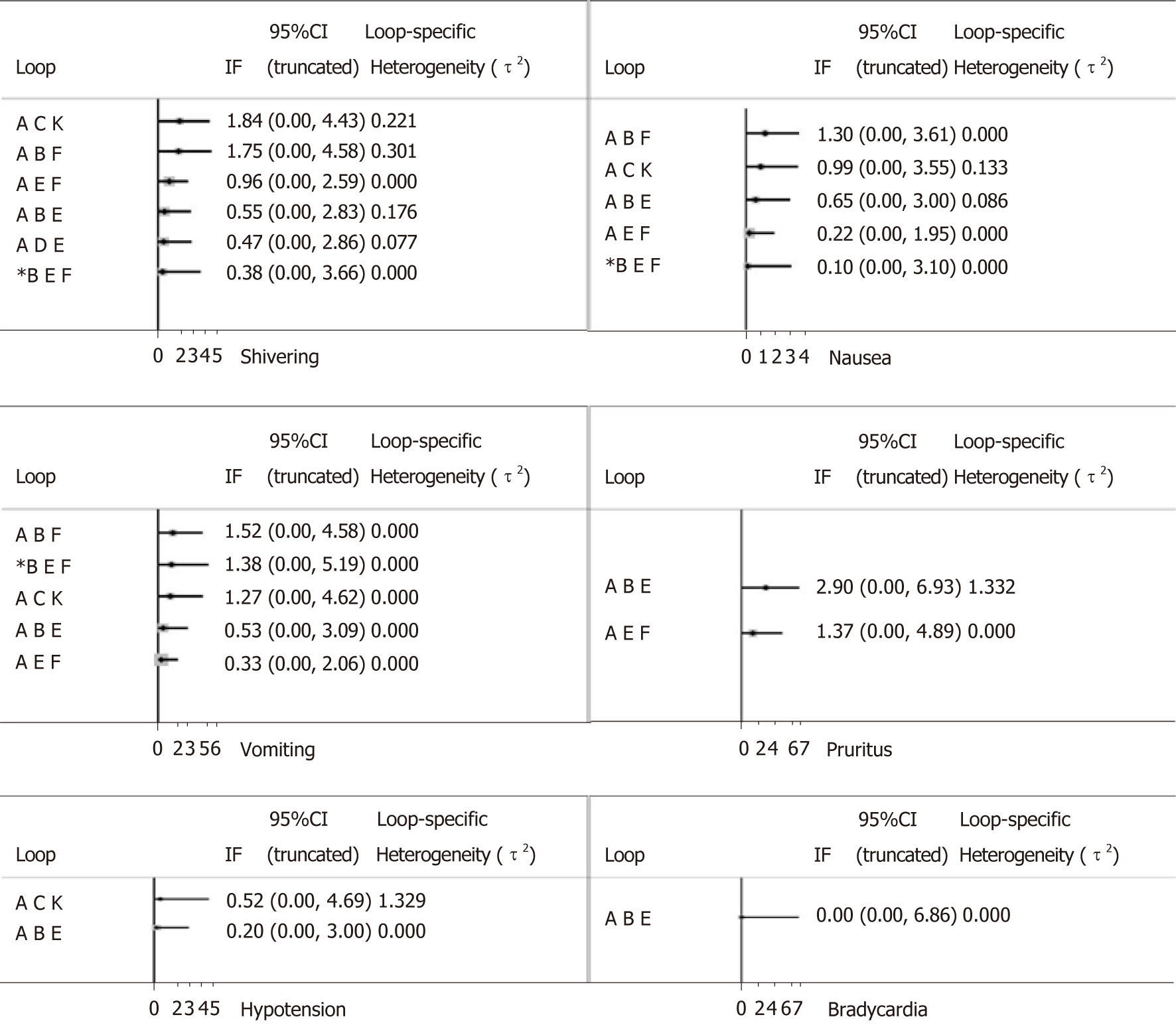

We used the node-splitting method to assess inconsistency. As shown in Figure 7, the majority of loops had no inconsistent results and the inconsistency of pruritus was relatively high compared with other outcomes.

Neuraxial anesthesia is widely used in lower abdominal surgery including cesarean section. Traditional neuraxial anesthesia only uses local anesthetic, which is often accompanied with the emergence of perioperative complications[35]. Shivering is one of the common complications of obstetric anaesthesia. Patients with shivering often suffer from uncontrolled muscular activity. The etiology of shivering is multiple and complicated. The risk factors responsible for shivering in puerperae undergoing caesarean sections may be intraoperative body heat and fluid loss, response to pain, or excitement of the sympathetic nervous system[36]. Because of the high incidence of shivering during caesarean section, the prevention of shivering has become an indispensable part of obstetric anaesthesia.

In current obstetric anaesthesia, combination of local anaesthetics and adjuvants has been a new choice for anesthetists to reduce side effects[37]. Several medications have been applied to obstetric anaesthesia as adjuvants and some of them have been reported to reduce shivering. We conducted the present NMA and comprehensively assessed the preventive effects of common adjuvants: Fentanyl, sufentanil, pethidine, morphine, dexmedetomidine, magnesium sulfate, clonidine, tramadol, and midazolam.

The results showed that pethidine, fentanyl, dexmedetomidine, and sufentanil had preventive effects on perioperative shivering during caesarean sections. Of note, pethidine, fentanyl, and sufentanil are opioids, and according to the research, opioids have a hyperthermic effect through the activation of μ-receptor, which might be the anti-shivering mechanism of opioids[38]. Moreover, compared with the other two opioids, pethidine has a better preventive effect on shivering. Several studies have indicated that the anti-shivering mechanisms of pethidine are different from those of other opioids. Besides activating the μ-receptors, it has a modulatory effect on shivering threshold and thermoregulation[39,40], which may help explain why pethidine has the highest rank of anti-shivering effect.

Dexmedetomidine is approved for procedural sedation use, but it is mainly for non-intravenous administration or peadiatric use. Recent studies have shown that dexmedetomidine may be a safe intrathecal supplement in Cesarean delivery[7,22].

Several studies demonstrated that α2 adrenoreceptor (α2-AR) agonists (including clonidine and dexmedetomidine ) have a potential prophylactic effect on shivering in patients[41,42]. Another study showed that α2-AR agonists markedly inhibited shivering in rats[43]. Dexmedetomidine is one of the emerging α2-AR agonists, possessing almost eight times higher α2-AR affinity compared to clonidine[44]. As our results indicated, clonidine had a weak preventive effect on shivering. Dexmedetomidine can quickly be absorbed and subsequently agitate α2-ARs in the spinal cord, leading to the inhibition of sympathetic activity and central thermoregulation[45]. The attenuation of hyperadrenergic response to perioperative stress could be another mechanism of action of dexmedetomedine for shivering control.

In terms of other adverse events, the present study indicated that pethidine significantly increased the risk of nausea and vomiting, while fentanyl significantly reduced the risk to the contrary. Both drugs are opioid receptor agonists and it is well known that opioids often increase the risk of nausea and vomiting in the clinical situation. The mechanism of nausea and/or vomiting after opioid use is complex[46]. However, interacting with μ-opioid receptors in the vomiting center may be the main mechanism of the anti-nausea and anti-vomiting effects of higher dose opioids[47]. Barnes et al[48] reported that the appropriate dose of fentanyl has a great inhibitory effect on drug-induced emesis. The different dose of opioids used as adjuvants may lead to the opposite results, which can help to explain the above findings of our study.

In addition, our study revealed that sufentanil significantly increased the incidence of pruritus than other drugs, including morphine, although pruritus was mostly mild, and no puerperae required treatment. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 7, the relatively high heterogeneity variance of pruritus, wide confidence interval, and potential inconsistency exist; further research is needed to confirm these findings.

The present analysis is the first NMA of the preventive effects of neuraxial adjuvants on perioperative shivering during caesarean section, revealing that pethidine, fentanyl, dexmedetomidine, and sufentanil could decrease the incidence of perioperative shivering in puerperae. In addition, our study comprehensively analyzed the effects of neuraxial adjuvants on the other adverse reactions, indicating the optimal adjuvant, which can not only prevent shivering, but also reduce other adverse events.

There are several limitations of this NMA. First, some outcomes, such as the Apgar score, could not be analyzed due to the lack of sufficient studies. Second, heterogeneity and potential risk of bias weakened the reliability of the results. Third, the incidence of adverse events may be confounded by different kinds of local anesthetic, the type of anesthesia, the dose of adjuvant, individual characteristic, or different type of intraoperative warming. Because of the limited number of included studies and inadequate information, the relevant subgroup analyses and stratified analyses were not possible.

In conclusion, the results of our study clearly suggest that, based on the available evidence, neuraxial pethidine, fentanyl, dexmedetomidine, and sufentanil are more efficacious than other medications in the prevention of shivering during caesarean sections. Although pethidine is the most effective adjuvant for shivering prevention, it significantly increases the incidence of nausea and vomiting. Considering the risk-benefit profiles of the included neuraxial adjuvants, fentanyl is probably the optimal choice.

Future clinical trials are still needed to further assess the efficacy and safety of neuraxial adjuvants for the puerperae and neonates, the optimal doses of the medications, and the timing of administration, etc., thus contributing to the establishment of a guideline of neuraxial adjuvant administration for obstetric anesthesia during caesarean sections.

Perioperative shivering is clinically common during caesarean section, and several neuraxial adjuvants have been used to prevent perioperative shivering. However, the effects of these neuraxial adjuvants and which one is preferred remain elusive.

To provide evidence for clinicians to choose the optimal neuraxial adjuvant to reduce perioperative shivering during cesarean section.

To evaluate the effects of different neuraxial adjuvants on perioperative shivering during cesarean section.

A systematic review and network meta-analysis (NMA) were conducted following the PRISMA guidelines. We performed a comprehensive search of PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Central databases for eligible clinical trials assessing the effects of neuraxial adjuvants on perioperative shivering. Analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.3 and Stata 14.0.

Pethidine, fentanyl, dexmedetomidine, and sufentanil are more efficacious than other medications in the prevention of shivering during caesarean sections. Among the above four adjuvants, pethidine was most effective for shivering prevention (OR = 0.15, 95%CI: 0.07-0.35, SUCRA 83.9), but with a high incidence of nausea (OR = 3.15, 95%CI: 1.04-9.57) and vomiting (OR = 3.71, 95%CI: 1.81-7.58). The efficacy of fentanyl for shivering prevention was slightly inferior to pethidine (OR = 0.20, 95%CI: 0.09-0.43), with a significantly decreased incidence of nausea (OR = 0.34, 95%CI: 0.15-0.79) and vomiting (OR = 0.25, 95%CI: 0.11-0.56). Furthermore, compared with sufentanil, fentanyl showed no impact on haemodynamic stability and the incidence of pruritus.

The results of this NMA indicated that neuraxial pethidine, fentanyl, dexmedetomidine, sufentanil appear to be more efficacious than other medications in the prevention of shivering during caesarean section. Considering the risk-benefit profiles of the included neuraxial adjuvants, fentanyl is probably the optimal choice for the prevention of perioperative shivering during cesarean section. Although several neuraxial adjuvants have been reported to prevent shivering during caesarean section, very few clinical trials directly compared the neuraxial adjuvants during caesarean section. Thus, it is currently impossible to perform a pairwise meta-analysis to directly compare the difference between two neuraxial adjuvants. More clinical trials that directly compare these neuraxial adjuvants (e.g., neuraxial pethidine vs fentanyl) are needed to fully explore the possible differences between the effects of these adjuvants.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cobucci RNO S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Gibbons L, Belizan JM, Lauer JA, Betran AP, Merialdi M, Althabe F. Inequities in the use of cesarean section deliveries in the world. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:331.e1-331.19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wong CA. Neuraxial Labor Analgesia: Does It Influence the Outcomes of Labor? Anesth Analg. 2017;124:1389-1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | de Figueiredo Locks G. Incidence of shivering after cesarean section under spinal anesthesia with or without intrathecal sufentanil: a randomized study. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2012;62:676-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ciofolo MJ, Clergue F, Devilliers C, Ben Ammar M, Viars P. Changes in ventilation, oxygen uptake, and carbon dioxide output during recovery from isoflurane anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1989;70:737-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Guffin A, Girard D, Kaplan JA. Shivering following cardiac surgery: hemodynamic changes and reversal. J Cardiothorac Anesth. 1987;1:24-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Khan ZH, Zanjani AP, Makarem J, Samadi S. Antishivering effects of two different doses of intrathecal meperidine in caesarean section: a prospective randomised blinded study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28:202-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | He L, Xu JM, Liu SM, Chen ZJ, Li X, Zhu R. Intrathecal Dexmedetomidine Alleviates Shivering during Cesarean Delivery under Spinal Anesthesia. Biol Pharm Bull. 2017;40:169-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Faiz SH, Rahimzadeh P, Imani F, Bakhtiari A. Intrathecal injection of magnesium sulfate: shivering prevention during cesarean section: a randomized, double-blinded, controlled study. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;65:293-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rastegarian A, Ghobadifar MA, Kargar H, Mosallanezhad Z. Intrathecal Meperidine Plus Lidocaine for Prevention of Shivering during Cesarean Section. Korean J Pain. 2013;26:379-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Abdollahpour A, Azadi R, Bandari R, Mirmohammadkhani M. Effects of Adding Midazolam and Sufentanil to Intrathecal Bupivacaine on Analgesia Quality and Postoperative Complications in Elective Cesarean Section. Anesth Pain Med. 2015;5:e23565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Crossley AW, Mahajan RP. The intensity of postoperative shivering is unrelated to axillary temperature. Anaesthesia. 1994;49:205-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews for interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org. |

| 13. | Wang XW, Liu ZT, Sui XB, Wu QB, Wang J, Xu C. Elemene injection as adjunctive treatment to platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with stage III/IV non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis following the PRISMA guidelines. Phytomedicine. 2018;. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Wu QB, Li GC, Lei WI, Zhou XQ. The efficacy and safety of tiotropium in Chinese patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis. Respirology. 2009;14:666-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Palmer CM, Voulgaropoulos D, Alves D. Subarachnoid fentanyl augments lidocaine spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Reg Anesth. 1995;20:389-394. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Shehabi Y, Gatt S, Buckman T, Isert P. Effect of adrenaline, fentanyl and warming of injectate on shivering following extradural analgesia in labour. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1990;18:31-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Han C, Jiang X, Wu X, Ding Z. Application of dexmedetomidine combined with ropivacaine in the cesarean section under epidural anesthesia. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2014;94:3501-3505. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Roy JD, Girard M, Drolet P. Intrathecal meperidine decreases shivering during cesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:230-234, table of contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Qi X, Chen D, Li G, Huang X, Li Y, Wang X, Li Y. Comparison of Intrathecal Dexmedetomidine with Morphine as Adjuvants in Cesarean Sections. Biol Pharm Bull. 2016;39:1455-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chen X, Qian X, Fu F, Lu H, Bein B. Intrathecal sufentanil decreases the median effective dose (ED50) of intrathecal hyperbaric ropivacaine for caesarean delivery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54:284-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bachmann-Mennenga B, Veit G, Biscoping J, Steinicke B, Heesen M. Epidural ropivacaine 1% with and without sufentanil addition for Caesarean section. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49:525-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nasseri K, Ghadami N, Nouri B. Effects of intrathecal dexmedetomidine on shivering after spinal anesthesia for cesarean section: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:1107-1113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hong JY, Lee IH. Comparison of the effects of intrathecal morphine and pethidine on shivering after Caesarean delivery under combined-spinal epidural anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:1168-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Agrawal A, Asthana V, Sharma JP, Gupta V. Efficacy of lipophilic vs lipophobic opioids in addition to hyperbaric bupivacaine for patients undergoing lower segment caeserean section. Anesth Essays Res. 2016;10:420-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hanoura SE, Hassanin R, Singh R. Intraoperative conditions and quality of postoperative analgesia after adding dexmedetomidine to epidural bupivacaine and fentanyl in elective cesarean section using combined spinal-epidural anesthesia. Anesth Essays Res. 2013;7:168-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Anaraki AN, Mirzaei K. The Effect of Different Intrathecal Doses of Meperidine on Shivering during Delivery Under Spinal Anesthesia. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:706-712. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Bajwa SJ, Bajwa SK, Kaur J, Singh A, Singh A, Parmar SS. Prevention of hypotension and prolongation of postoperative analgesia in emergency cesarean sections: A randomized study with intrathecal clonidine. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2012;2:63-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bi YH, Cui XG, Zhang RQ, Song CY, Zhang YZ. Low dose of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to bupivacaine in cesarean surgery provides better intraoperative somato-visceral sensory block characteristics and postoperative analgesia. Oncotarget. 2017;8:63587-63595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yousef AA, Amr YM. The effect of adding magnesium sulphate to epidural bupivacaine and fentanyl in elective caesarean section using combined spinal-epidural anaesthesia: a prospective double blind randomised study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2010;19:401-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Subedi A, Biswas BK, Tripathi M, Bhattarai BK, Pokharel K. Analgesic effects of intrathecal tramadol in patients undergoing caesarean section: a randomised, double-blind study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2013;22:316-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Qian XW, Chen XZ, Li DB. Low-dose ropivacaine-sufentanil spinal anaesthesia for caesarean delivery: a randomised trial. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2008;17:309-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sadegh A, Tazeh-Kand NF, Eslami B. Intrathecal fentanyl for prevention of shivering in spinal anesthesia in cesarean section. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2012;26:85-89. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Techanivate A, Rodanant O, Tachawattanawisal W, Somsiri T. Intrathecal fentanyl for prevention of shivering in cesarean section. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005;88:1214-1221. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Shami S, Nasseri K, Shirmohammadi M, Sarshivi F, Ghadami N, Ghaderi E, Pouladi M, Barzanji A. Effect of low dose of intrathecal pethidine on the incidence and intensity of shivering during cesarean section under spinal anesthesia: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:3005-3012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Schug SA, Saunders D, Kurowski I, Paech MJ. Neuraxial drug administration: a review of treatment options for anaesthesia and analgesia. CNS Drugs. 2006;20:917-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bozgeyik S, Mizrak A, Kılıç E, Yendi F, Ugur BK. The effects of preemptive tramadol and dexmedetomidine on shivering during arthroscopy. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8:238-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Koyyalamudi V, Sen S, Patil S, Creel JB, Cornett EM, Fox CJ, Kaye AD. Adjuvant Agents in Regional Anesthesia in the Ambulatory Setting. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017;21:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Rawls SM, Benamar K. Effects of opioids, cannabinoids, and vanilloids on body temperature. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). 2011;3:822-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Ikeda T, Kurz A, Sessler DI, Go J, Kurz M, Belani K, Larson M, Bjorksten AR, Dechert M, Christensen R. The effect of opioids on thermoregulatory responses in humans and the special antishivering action of meperidine. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;813:792-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | De Witte J, Sessler DI. Perioperative shivering: physiology and pharmacology. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:467-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Weant KA, Martin JE, Humphries RL, Cook AM. Pharmacologic options for reducing the shivering response to therapeutic hypothermia. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:830-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Logan A, Sangkachand P, Funk M. Optimal management of shivering during therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Crit Care Nurse. 2011;31:e18-e30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Madden CJ, Tupone D, Cano G, Morrison SF. α2 Adrenergic receptor-mediated inhibition of thermogenesis. J Neurosci. 2013;33:2017-2028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Rutkowska K, Knapik P, Misiolek H. The effect of dexmedetomidine sedation on brachial plexus block in patients with end-stage renal disease. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2009;26:851-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Zhang J, Zhang X, Wang H, Zhou H, Tian T, Wu A. Dexmedetomidine as a neuraxial adjuvant for prevention of perioperative shivering: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Herndon CM, Jackson KC 2nd, Hallin PA. Management of opioid-induced gastrointestinal effects in patients receiving palliative care. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:240-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Scotto di Fazano C, Vergne P, Grilo RM, Bertin P, Bonnet C, Trèves R. Preventive therapy for nausea and vomiting in patients on opioid therapy for non-malignant pain in rheumatology. Therapie. 2002;57:446-449. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Barnes NM, Bunce KT, Naylor RJ, Rudd JA. The actions of fentanyl to inhibit drug-induced emesis. Neuropharmacology. 1991;30:1073-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |