Published online Aug 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2256

Peer-review started: March 6, 2019

First decision: May 10, 2019

Revised: July 18, 2019

Accepted: July 27, 2019

Article in press: July 27, 2019

Published online: August 26, 2019

Processing time: 173 Days and 7 Hours

Allergy to cow’s milk is the most frequent allergy occurring in infants and young children. The dietary management of these patients consists of the elimination of any cow’s milk proteins from the diet, and for formula-fed infants, the substitution of the usual infant formula with an adapted formula that is generally based on extensively hydrolyzed cow’s milk proteins. The American Academy of Pediatrics has established specific criteria to confirm the hypoallergenicity of a formula intended for these children.

To assess the hypoallergenicity of a new thickened extensively hydrolyzed casein-based formula (TeHCF) in children with cow’s milk allergy (CMA).

Children diagnosed with CMA through a double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) were randomly administered increased doses of a placebo formula or the TeHCF [Allernova, new thickener including fibres (Novalac)] under double-blind conditions and medical surveillance on two separate days. Otherwise, both of these formulas and a cow’s milk-based formula were randomly introduced to children who were highly suspected of having CMA on three separate days. Immediate and late reactions occurring after the introduction of any of these formulas were thoroughly recorded by the physician at the hospital and reported by parents to the physician after hospital discharge, respectively. If the children tolerated the TeHCF during the DBPCFC, they were exclusively fed this formula during a 3-mo period where potential allergic symptoms, anthropometric parameters, as secondary outcomes, and adverse events were registered. The Cow’s Milk-related Symptoms Score (CoMiSSTM) was assessed and anthropometric parameters were compared to World Health Organization (WHO) reference data.

Of the 30 children included in the study, the CMA diagnosis of 29 (mean age: 8.03 ± 7.43 mo) patients was confirmed by a DBPCFC. The children all tolerated the TeHCF during both the challenge and the subsequent 3-mo feeding period, which they all completed. During the latter period, the CoMiSSTM remained at a very low level, never exceeding its baseline value (1.4 ± 2.0), growth parameters were within WHO reference standards and no adverse event related to the TeHCF was reported. Over the first week of this period, the proportion of patients with digestive discomfort significantly decreased from 20.7% (6/29) to 3.4% (1/29), P = 0.025. The proportion of satisfaction with the overall effect of the formula reported by the parents and investigator was high, as was the formula acceptability by the child.

The new TeHCF meets the hypoallergenicity criteria according to the American Academy of Pediatrics standards, confirming that the tested TeHCF is adapted to the dietary management of children with CMA. Moreover, growth was adequate in the included population.

Core tip: The hypoallergenicity of the new tested formula as the primary criterion was rigorously confirmed through a properly designed double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) in children with a diagnosis of cow’s milk allergy (CMA) that was confirmed by a DBPCFC, the gold standard diagnostic procedure for food allergies. The subsequent 3-mo open exclusive feeding with the tested formula showed that the formula was still well tolerated by the 29 children with CMA included, their growth was adequate, and parents and the investigator were very satisfied with the effect of the formula.

- Citation: Rossetti D, Cucchiara S, Morace A, Leter B, Oliva S. Hypoallergenicity of a thickened hydrolyzed formula in children with cow’s milk allergy. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(16): 2256-2268

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i16/2256.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2256

In the EuroPrevall birth cohort, the incidence of cow’s milk allergy (CMA) was reported to range from 1% to less than 0.3% in European children up to age 2, depending on the country considered[1]. The most rigorous food allergy diagnosis procedure, the double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC), was used, and only allergic reactions occurring within 2 h of the DBPCFC and/or an increase in eczema within 48 h were considered for the CMA diagnosis, which might explain the very low incidences reported in some countries. In addition, the screening procedure might have lacked sensitivity for non-immunoglobulin (Ig) E-mediated gastrointestinal (GI) manifestations[2]. The CMA prognosis was quite good, as all children with non IgE-mediated CMA tolerated cow’s milk as soon as one year after diagnosis and approximately 60% of children with IgE-mediated CMA displayed tolerance[1]. According to paediatric guidelines, the cornerstone of CMA dietary management is the implementation of a cow’s milk protein (CMP) elimination diet. For non-breastfed infants and young children, it mainly consists of feeding them special infant formulas whose protein fraction comprises extensively hydrolyzed CMP (eHF), soy or rice proteins[3,4,5,6,7]. These formulas are well tolerated by most children with CMA. However, up to 10% of these children may react to eHF. In these cases, or when CMA is severe, the use of an amino-acid based formula (AAF) is recommended[6,7]. The American Academy of Pediatrics established criteria to determine the hypoallergenicity of any formula intended for children with CMA[8]. The primary objective of this study was therefore to evaluate the hypoallergenicity of a new thickened extensively hydrolyzed casein-based formula (TeHCF) in children with CMA proven by a DBPCFC.

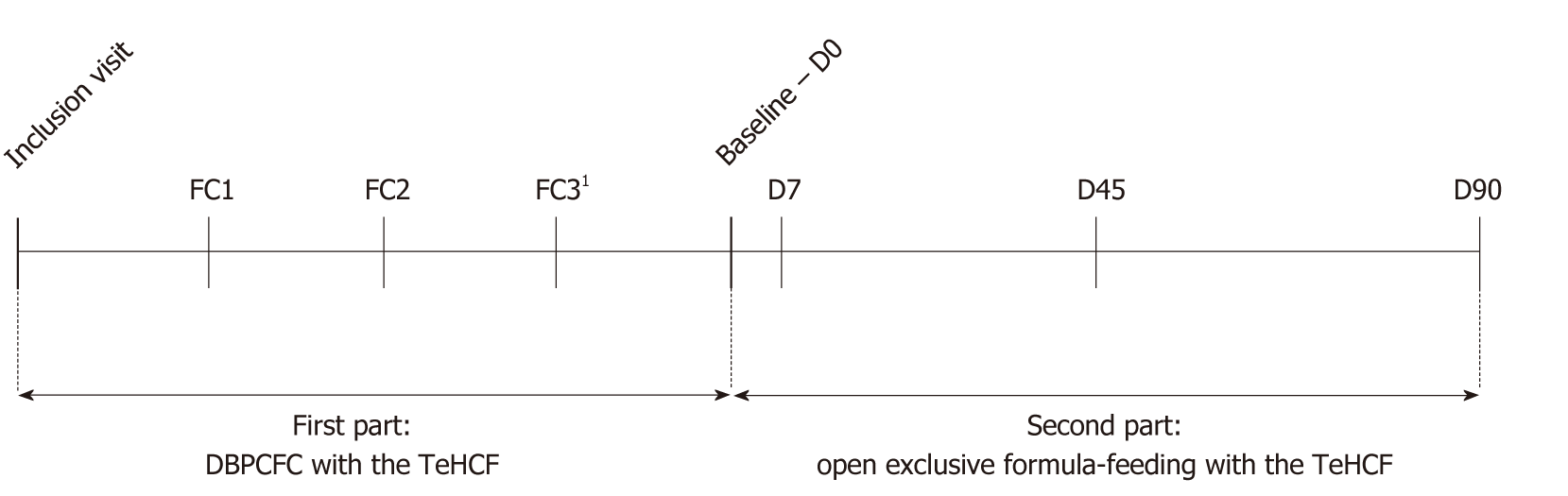

The primary outcome was the tolerance/hypoallergenicity of the tested formula, which was defined as the absence of intolerance during the DBPCFC with the TeHCF in infants with a proven CMA. In addition, CMA symptoms, growth, tolerance of the study formula and investigator’s and parents’ satisfaction with the study formula were analysed as secondary outcomes. This clinical trial comprised two phases, the first consisting of the DBPCFC with the TeHCF, and the second consisting of exclusive TeHCF feeding for 3 mo (Figure 1) by all patients. Once reconstituted, the tested study formula [Allernova, new thickener (Novalac, United Pharmaceuticals, Paris, France)] had an energy density of 67 kcal/100 ml and contained 1.6, 3.5, 6.9 and 0.5 g of proteins, lipids (including arachidonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid), carbohydrates and fibre per 100 mL, respectively. The new thickener was a patented mix of fibres, including pectin and locust bean gum. The formula was lactose free and complied with the European regulation in force at the start of the study[9].

Infants (1) Aged between 1 and 36 mo old; (2) Who were strongly suspected of having CMA or were diagnosed with a CMA that was confirmed by a DBPCFC performed within the last 2 mo; (3) Successfully fed an elimination diet for at least 2 wk as recommended by guidelines on food challenge procedures[10,11] and (4) Whose parents signed the informed consent form were included. The main exclusion criteria were the exclusive or major consumption of mother’s milk at study enrolment, a past anaphylactic reaction, a history of a lack of improvement of allergic symptoms when previously fed an eHF since for these children an AAF is recommended[4,6,7,8], or any situation that, according to the investigator, might interfere with study participation.

If a CMA was already proven by a DBPCFC before study inclusion, the child underwent a 2-d DBPCFC: the placebo formula, namely, an AAF (Neocate, Nutricia), or the TeHCF were introduced in a random order on two different days [food challenge (FC) 1 and FC2] separated by at least 7 d. Otherwise, a “combined food challenge” was conducted: the placebo formula, the TeHCF and a cow’s milk-based formula were introduced in a random order on three different days (FC1, FC2 and FC3), each separated by at least 7 d. This schedule was chosen since participation in two DBPCFCs, one to assess the hypoallergenicity of the TeHCF and one to prove CMA, would have been too cumbersome for both parents and the child.

Before each FC day at the hospital, the investigator ensured that the child did not present any clinical abnormalities and had stopped all medications including antihistamines that could have interfered with the administration of the challenge. Increased volumes of TeHCF, placebo or cow’s milk-based formula were fed to the child in a blinded manner every 20 min under medical supervision. The placebo formula and the TeHCF were reconstituted according to the manufacturer’s instructions; for blinding, the latter was mixed with the placebo formula at a 2:1 ratio. The cow’s milk-based formula was standard infant formula, full fat or semi-skimmed cow’s milk, that was mixed with or without the placebo formula, according to the usual practice of the service. The prescribed schedule was 0.5, 1, 3, 10, 30, 50 and 100 mL. The administered formulas were prepared by a staff member who was not involved in the patient’s care. The investigator, the nursing staff, and the family were therefore not informed of what formula the child was being fed.

All objective and subjective symptoms were registered using a standardized symptom score[10,11] (Supplementary Table 1). If subjective clinical symptoms occurred, the last dose administered was repeated without an increase. The challenge was normally pursued in the absence of objective symptoms; otherwise, it was stopped, and the child was treated as deemed necessary by the investigator. The child was monitored for 2 h after the administration of the last dose, or longer if required according to his condition.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Age, mo | 8.03 (7.43) |

| Male | 16 (55.2) |

| Anthropometric characteristics at birth | |

| WFA z-score, mean ± SD | 0.1 (1.0) |

| LFA z-score, mean ± SD | 0.2 (1.3) |

| HCA z-score, mean ± SD | 1.0 (1.0) |

| Gestational age, mean ± SD, wk | 38.5 (2.3) |

| Preterm | 6 (20.7) |

| Anthropometric characteristics at inclusion | |

| WFA z-score, mean ± SD | -0.3 (1.2) |

| LFA z-score, mean ± SD | 0.0 (1.4) |

| WFL z-score, mean ± SD | -0.4 (1.0) |

| BMI-for-age z-score, mean ± SD | -0.4 (1.0) |

| HCA z-score, mean ± SD | 0.7 (1.2) |

| Feeding history | |

| Breastfeeding in the past | 22 (75.9) |

| Duration of (exclusive and/or partial) breastfeeding, mean ± SD, wk | 17.6 (16.2) |

| Duration of feeding with the formula taken before inclusion, mean ± SD, wk | 10.8 (13.1) |

| Average volume of the formula taken before inclusion, mean ± SD, mL/d | 655.2 (199.3) |

| Solid foods diversification | 18 (62.1) |

| Allergy history | |

| At least one parent or sibling with a medically confirmed allergy | 14 (48.3) |

| Parents’ smoking habits | |

| Past only | 5 (17.2) |

| Current | 11 (37.9) |

| Mother only | 4 (13.8) |

| Father only | 6 (20.7) |

| Both parents | 1 (3.4) |

| Age at onset of first CMA symptoms, mean ± SD, mo | 3.6 (4.4) |

| Time since beginning of the elimination diet, median (min–max; IQR), wk | 8.3 (2.0–125.3; 9.7) |

| Time elapsed between the onset of allergy symptoms and the initiation of the elimination diet, median (min – max; IQR), wk | 1.9 (0.1-46.0; 5.7) |

| Type of first CMA symptoms | |

| Exclusively digestive | 10 (34.5) |

| Exclusively cutaneous | 2 (6.9) |

| Digestive and cutaneous | 3 (10.3) |

| Digestive symptoms and other symptoms such as crying, irritability, abdominal pain, and agitated sleep | 5 (17.2) |

| Digestive symptoms and failure to thrive | 6 (20.7) |

| Digestive, cutaneous and other symptoms such as crying, irritability, and agitated sleep | 3 (10.3) |

| Delay of first CMA symptoms | |

| Immediate | 1 (3.4) |

| Delayed | 28 (96.6) |

| Type of food triggering the first CMA symptoms | |

| Mother’s milk | 4 (13.8) |

| Infant formula | 25 (86.2) |

Once at home and until the next FC day, the child continued his usual CMP elimination diet by being fed the formula that was successfully consumed before study inclusion; moreover, his parents were instructed not to introduce any new foods. The child’s parents noted any change in their usual child’s regurgitations, stools, or mood in a diary to detect any late-occurring reactions on each FC day and the two subsequent days. The parents also recorded the appearance of any allergic symptoms within the week after each FC day. At the onset of any delayed reaction, the parents were advised to immediately contact the investigator to discuss further actions. At the end of each follow-up period, the child was clinically examined and the potential symptoms reported by his parents were assessed by the investigator with regard to allergy.

If the TeHCF was tolerated during the DBPCFC and the CMA was confirmed, the child continued the study and started the open exclusive formula-feeding with the TeHCF at D0 visit (also named Baseline visit, Figure 1) that consisted of a total replacement of the substitution formula used before D0 visit by the TeHCF. In addition, the child continued his usual CMP elimination diet. Then, the child was monitored at a consultation on days 7, 45 and 90 (D7, D45 and D90 visits). On each of these visits, the investigator asked parents about the presence of potential allergic symptoms in their child. Based on this information, the investigator administered the Cow’s Milk-related Symptoms Score (CoMiSSTM), a tool aiming to evaluate and quantify the evolution of symptoms during therapeutic interventions[12]. CoMiSSTM consists of 6 sub-scores and ranges from 0 to 33 points (Supplementary Table 2). If eczema was present, the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index was also measured[13]. As the SCORAD index has previously been reported during dietary interventions in infants with CMA and eczema, it was chosen for comparison purposes. The frequency of vomiting episodes and the intensity of digestive discomfort were assessed using 4-item scales (Supplementary Table 2). The presence of angioedema and blood in stools were noted; the mean number of stools passed on the last three days, the child’s sleep quality (quiet, i.e., the absence of or few awakenings, or agitated, i.e., excessive waking with no clear cause) and the parental satisfaction with the child’s sleeping time were registered. The compliance was evaluated by the investigator at each visit by asking parents if the child accepted the formula’s taste, if he/she had stopped the exclusive formula-feeding with the TeHCF or if he/she had taken another formula and what was the average volume of TeHCF taken by the child over the last 3 d. In case of poor compliance to feeding recommendation, or definitive interruption of the TeHCF feeding, the investigator could decide to end the child’s study participation. The investigator also ranked his overall satisfaction with the effect of the study formula on the child using a 4-item scale ranging from very unsatisfied to very satisfied. Body weight, length and head circumference were recorded at each study visit. Adverse events experienced by all patients included in the study who received at least one of the two or three products administered on FC days were monitored.

| Characteristics of patients with immediate reactions (n = 5) | |

| Types of reactions | |

| Objective gastrointestinal complaints | 5 (100.0) |

| Severe reaction | 1 (20.0) |

| Moderate reaction | 1 (20.0) |

| Mild reaction1 | 3 (60.0) |

| Time of reaction after the ingestion of first CMP dose, mean ± SD, min | 98.0 (4.5) |

| Eliciting dose of CMP, mean ± SD, g | 2.2 (1.3) |

| Cumulative dose of CMP, mean ± SD, g | 4.7 (2.9) |

| Characteristics of patients with delayed reactions only (n = 24) | |

| Types of reactions | |

| Digestive and cutaneous symptoms2 | 2 (8.3) |

| Upper digestive symptoms (regurgitations and vomiting)2 | 8 (33.3) |

| Lower digestive symptoms (changes in stools frequency/consistency and bloody stools)2 | 9 (37.5) |

| Lower and upper digestive symptoms2 | 3 (12.5) |

| Eczema | 1 (4.2) |

| Irritability/crying3 | 1 (4.2) |

| Cumulative dose of CMP, mean ± SD, g | 3.9 (1.8) |

| Time of reaction after hospital discharge | |

| Within 6 h | 11 (45.8) |

| Between 6 and 12 h | 5 (20.8) |

| > 24 h | 8 (33.4) |

During the first 7 d of the open feeding with TeHCF, and 3 d before the D45 and D90 visits, parents noted the volumes of formula consumed by the child, the types of foods eaten, and the same parameters recorded in the diaries after FC days. They also rated their satisfaction and the formula acceptability by their child, from very unsatisfied to very satisfied.

The results of atopy patch test (APT), Skin Prick Test (SPT) and the determination of the dosage of specific IgE (sIgE) to any type of allergen performed before or during the study period, and if deemed necessary by the investigator according to his usual practice, were registered. The APT was conducted as recommended[14] with a specific patch test system on which fresh cow’s milk and a negative control were placed. The SPT was performed using the appropriate specific allergen extracts and positive and negative controls; the tests were interpreted 15 – 20 minutes after application. The dosage of serum sIgE was determined with a standardized ELISA. IgE-mediated CMA was defined as the presence of one sIgE to CMP (α-lactalbumin, β- lactoglobulin or casein) at a concentration greater than 0.1 kU/L in plasma or, for the SPT, a difference in the diameter between CMP wheal and negative control greater than 3 mm.

The study was conducted in the Pediatric Gastroenterology, Liver and Digestive Endoscopy Unit of University Hospital Umberto I, Roma, Italy. The study protocol was approved by the independent Ethics Committee of the Sapienza University, Roma, Italy. This study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards established in the Declaration of Helsinki. Parents/legal guardians provided written consent regarding their willingness to participate and the study procedures.

A formula must show at 95% confidence that it does not provoke allergic reactions in 90% of subjects with a confirmed CMA to be considered hypoallergenic[8]. In a study with a binomial outcome (reaction versus no reaction), the sample size is determined by calculating a binomial confidence interval (CI) for p, the probability of having a reaction, as reported in a previous study[15] . In the case of 0 observed reactions, the upper 95%CI for P is < 0.10 when the sample size is 29 participants. Thus, a study including at least 29 subjects in which none were classified as positive in the DBPBFC enables the investigator to conclude that the study provided 95% confidence that at least 90% of children with a confirmed CMA who ingest the tested formula would not experience a reaction. The primary criterion was assessed using the hypoallergenic population, namely, patients with a proven CMA and complete DBPCFC. A DBPCFC was considered as complete when the child was administered the FC on all days (two or three days) and was monitored at a consultation up to 7 d after each FC day. The secondary outcomes were evaluated using patients from the hypoallergenic population who completed the second part of the study.

All statistical analyses were performed at the 0.05 global significance level using two-sided tests. Data obtained at each visit were compared to baseline data (D0 visit corresponding to the start of exclusive formula-feeding with the TeHCF) using a Wilcoxon test or Student’s t-test for quantitative parameters, depending on the normality of the distribution. For qualitative parameters, McNemar’s test or a symmetry test (if more than 2 classes) was used. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2.

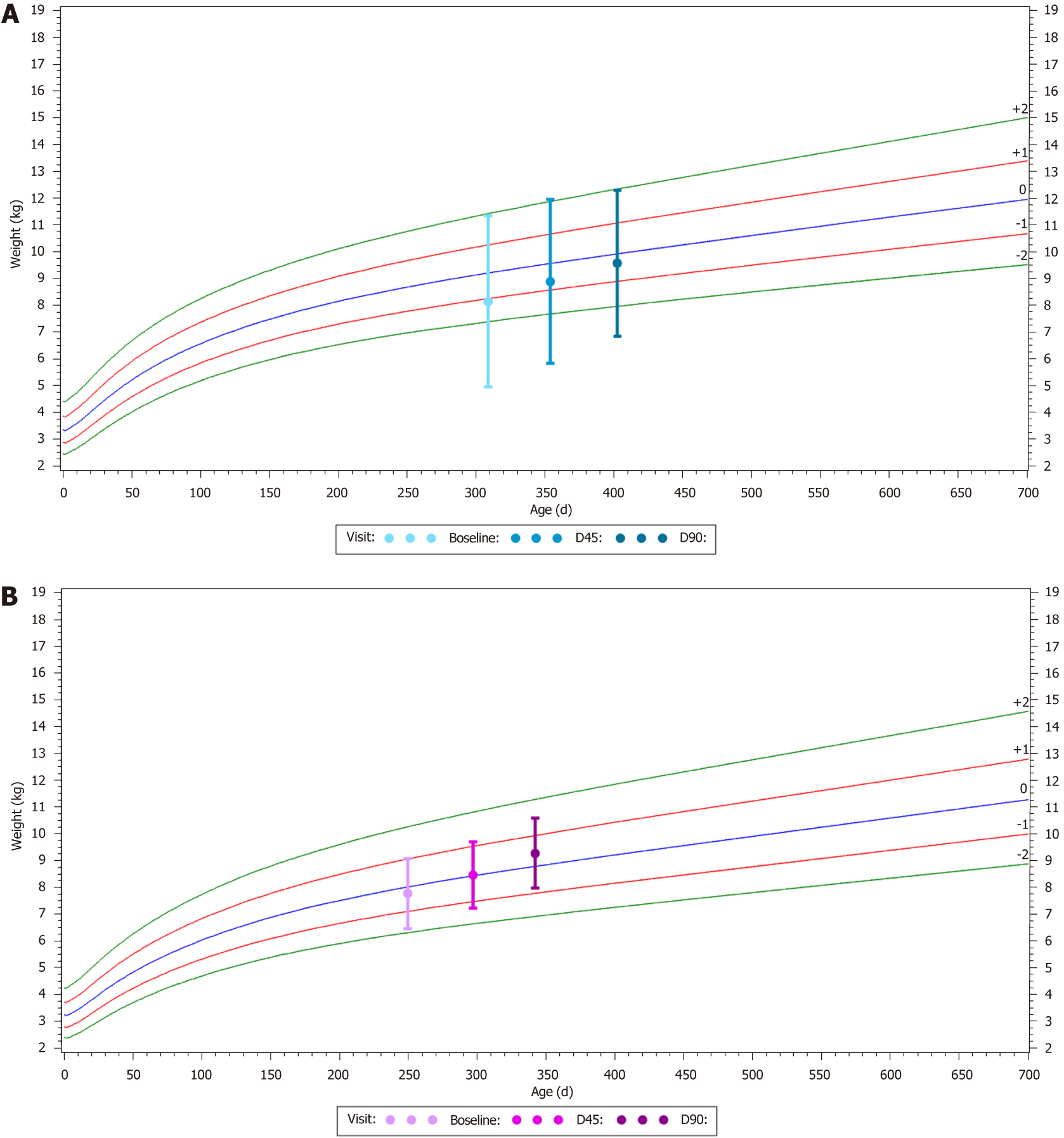

The body mass index (BMI) was calculated and z-scores of weight-for-age (WFA), length-for-age (LFA), weight-for-length (WFL), BMI-for-age and head circumference-for-age (HCA) were computed based on World Health Organization (WHO) growth standards for healthy breastfed infants[16]. Specific charts were used for preterm infants less than 64 wk of postmenstrual age[17]. For older preterm infants, z-scores were computed using WHO growth charts and the corrected age.

Thirty patients were included in this clinical trial from April 2016 to July 2017. One patient did not have a confirmed CMA and was therefore excluded from the hypoallergenic population. The remaining 29 patients were aged from 1 to 31 mo at inclusion (median age: 6 mo). At that time, 4 patients were partially breastfed, but their mother’s diet was devoid of CMP. Twenty-two subjects were fed an eHF and 7 a vegetable-based infant formula: One was fed a rice-based drink not adapted to infant feeding and the other 6 were fed a rice-based infant formula. Other characteristics of the patients’ feeding history are detailed in Table 1.

At inclusion, subjects had received a CMP elimination diet for an average of 15.6 ± 24.8 wk. One patient also eliminated egg albumen and soy. Other details on the allergic history are described in Table 1. Of the 3 patients on whom an APT to cow’s milk was performed, only one showed a moderate reaction. Three of 9 patients had a positive SPT to cow’s milk. Another patient underwent a blood test for sIgE to CMP and the titre of the antibodies against β-lactoglobulin exceeded 0.35 kU/L; therefore, 4 patients were considered as having an IgE-mediated CMA. One patient had a positive SPT to cat, another to egg albumen and house dust mites, and another to tomatoes.

The CMA of 19 patients was confirmed by a DBPCFC that was performed at an average of 2.7 ± 1.8 wk before study inclusion. In the hypoallergenic population, 5 patients experienced an immediate reaction after cow’s milk introduction, i.e., within 2 h after the last administered dose, and 24 only experienced delayed reactions (Table 2).

All patients tolerated the TeHCF; none showed an immediate or delayed reaction after having ingested the entire planned volume of formula. Likewise, all patients tolerated the placebo formula. During the food challenge follow-up, parents of one patient reported an increase in regurgitations and irritability after the administration of the TeHCF; parents of another child noticed a higher frequency of stools and a change in their consistency, although these changes were also reported after the administration of the placebo formula. Finally, the parents of 2 other children reported changes after the administration of the placebo formula: For one, a higher stool frequency and lower stool consistency and for the other, irritability and an increase in crying duration. The investigator did not consider any of these changes as allergic reactions related to the TeHCF or placebo formula.

All patients were fed the TeHCF for the open 3-mo period and none dropped out of the study due to intolerance to the formula, poor compliance to feeding recommendation or definitive interruption of the TeHCF feeding. No significant differences in CoMiSSTM or any of its sub-scores were noted between the baseline and D7. The TeHCF was therefore well tolerated when consumed as the exclusive formula. At baseline, the CoMiSSTM score was very low, on average 1.4 ± 2.0. Notably, 51.7% (15/29) of patients had a null CoMiSSTM score and the maximum CoMiSSTM score was 6 for only 3 patients (10.3%). After 7 d of treatment, the mean CoMiSSTM score decreased slightly to 0.7 ± 1.2, and remained very low, never exceeding the mean baseline CoMiSSTM score, during the entire course of the study.

At baseline, the most severe intensity of regurgitations on the CoMiSSTM scale was observed for only 3 patients who experienced more than 5 episodes of regurgita-tions/day with a volume of more than one coffee spoon; at D7, regurgitations improved for all these patients. The stools sub-score was also very low at baseline, an average of 0.62 ± 1.21, and did not change significantly throughout the study. Additionally, 20.7% (6/29) of patients cried for more than 1.5 h daily at baseline; after 7 d of TeHCF feeding, only 3.4% (1/29) of patients cried for more than 1.5 h per day, this change tended to be statistically significant (P = 0.06). One patient presented eczema lesions: The SCORAD index decreased from 20.5 at D0 to 5.1 at D45. None of the patients presented urticaria or respiratory symptoms from baseline to the end of the study. Vomiting was reported for only one patient on one visit (D45), and another patient presented bloody stools also only once during the study (D90). Notably, 20.7% (6/29) patients presented digestive discomfort at baseline; this percentage significantly decreased after 7 d of TeHCF feeding to 3.4% (1/29, P = 0.025).

The majority of patients (51.7%, 15/29) did not show changes in their daily stool frequency, which remained in the normal range throughout the study, i.e., from 1 to 4 stools passed/day[18]. During the entire study course, the great majority of parents (86.2% (25/29)) were satisfied with the sleeping time of their child. At baseline, approximately 90% of patients (26/29) experienced quiet sleep; this proportion reached 96.6% at D90.

The mean WFA z-score significantly increased from -0.3 ± 1.2 at baseline to -0.2 ± 1.3 at D45 (P = 0.025) and to 0.1 ± 1.2 at D90 (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). The same significant evolution was observed for the mean WFL and BMI z-scores, which were also slightly negative (Table 3) at baseline and increased by 0.3 ± 0.6 and 0.6 ± 0.9 after 45 and 90 d of TeHCF feeding, respectively.

At each visit and for all patients, the investigator was satisfied or very satisfied with the overall effect of the formula. Regardless of whether they were interviewed after seven or 45 d of TeHCF feeding, more than 80% of parents were satisfied to very satisfied with the global effect of the formula (Supplementary Figure 1). Moreover, throughout the study, more than 85% of parents were satisfied to very satisfied with the formula acceptability by their child.

All children in the hypoallergenic population complied to feeding recommenda-tions, with the exception of 5 who were introduced to a new food allergen within days following the challenge with CMP, but without consequence, as these foods were subsequently consumed with no reaction reported. On average, the patients consumed between 500 to 600 ml of TeHCF throughout the study and their diet was strictly devoid of CMP.

Children participated in the study for an average of 112.5 ± 20.7 d and were fed the study formula for 90.4 ± 17.2 d. Except for reactions observed after cow’s milk introduction in patients exposed to a combined challenge, only one adverse event was reported (viral gastroenteritis) during the study and was not considered related to the TeHCF.

Based on the findings of the present study, the new TeHCF tested in children with a proven CMA and which correspond to the patient population the most likely to benefit from this type of formula, i.e. children aged 0-36 mo, meets the criteria of hypoallergenicity according to the AAP[8]. No allergic reactions were noted after the ingestion of this TeHCF, whether it was progressively administered at increasing doses under medical surveillance at the hospital or when consumed as the exclusive formula at home under the parents’ observation. In addition, children who were fed the tested TeHCF for 3 mo showed increased growth z-scores within WHO reference standards. In conclusion, the new TeHCF is hypoallergenic and appropriate for consumption by children who are allergic to CMP because of its good tolerance and safety.

The methodology adopted in this study was rigorous. First, the CMA was proven through a DBPCFC, the strictest diagnostic tool, and the same procedure was used to introduce the TeHCF. In addition, immediate reactions occurring during food challenge were graded using an allergy symptoms scale derived from the PRACTALL consensus report[10] to ensure that each subject’s challenge was conducted, monitored, and interpreted in a uniform manner. Finally, children who were highly suspected of having a CMA were included in that study, but underwent a combined food challenge. This approach was used to avoid the excessive burden imposed by 2 DBPCFCs on children and their parents. Therefore, the introduction of the placebo formula was not repeated and was used for both the CMA diagnosis and the evaluation of the TeHCF hypoallergenicity. Conversely, no control group was investigated during the second study phase, which is the main methodological limitation of this clinical trial. The TeHCF could have been compared to a control formula, especially for the evaluation of the satisfaction of the formula effect by clinician and parents. However, the design was adequate for confirming the hypoallergenicity of the new TeHCF in allergic children, the primary objective of the present study. Another limitation is that information on late reactions after the introduction of cow’s milk, TeHCF or placebo formula was initially obtained from the parents. However, the hospitalization of children for more than a day to perform a DBPCFC is hardly feasible. Moreover, children were clinically re-examined by the investigator and parents were required to accurately register the occurrence of any delayed reactions in diaries, as already performed before[19,20] to enable their objective evaluation by the investigator at follow-up visit.

When tested for a CMA diagnosis, most children reacted within the day following the introduction of intact CMP, highlighting the importance of the open feeding period to ensure that no delayed symptoms will appear after the first introduction of a new formula. The AAP requests a 7-d open feeding period and a proper monitoring of the onset of potential symptoms to confirm the hypoallergenicity of a formula[8]. Some studies employing a similar design to the present clinical trial also included an open feeding period where parents were requested to note any occurrence of allergic symptoms. Among the most recent studies, in 30 infants with CMA who underwent a DBPCFC with an AAF, no serious adverse events were reported during the ensuing 7-d feeding period that was completed by 24 patients[20]. Another AAF was tested in 30 of 33 included children with CMA during a similar period[19]. Vomiting (4 subjects) due to the formula palatability, erythema for one subject, itchy skin on the back for one subject and a mild stomach ache in another subject appeared but then subsided, and the consumption of the AAF was not discontinued. The tested TeHCF showed a good tolerance as well: none of the patients ceased its consumption during the open exclusive formula feeding period, and the CoMiSSTM decreased slightly after the first 7-day feeding period.

Globally, during the second study phase, the CoMiSSTM remained at a low level, in contrast to findings reported in previous studies, i.e., significant decreases in CoMiSSTM after interventions with therapeutic formulas such as eHCF, eHF based on whey proteins or rice-based infant formula[21,22,23,24]. In the present study, children were asymptomatic for at least two weeks upon inclusion and then underwent the DBPCFC with an at least one-week interval between each FC day to allow potential symptoms to resolve. Between each FC day and until the start of the exclusive formula-feeding with the TeHCF (i.e., at Baseline – D0 visit), the child was fed the formula that was successfully consumed before study inclusion; thus, the CoMiSSTM was very low at baseline. The tolerance of the new TeHCF was evidenced by the maintenance of the CoMiSSTM at a low level when children were exclusively fed this formula. Recently, the mean CoMiSSTM score of 413 healthy infants (median age: 7.0 wk) was reported to be 3.7 ± 2.9[25], which was higher than the mean CoMiSSTM reported at baseline in the present study 1.4 ± 2.0; the difference might be explained by the lower median age of the healthy infants (7 wk) than the included children (7 mo at baseline).

An increasing amount of data on the growth of children with food allergies, particularly CMA, is accumulating[26,27]. Children with food allergies might indeed be at risk of growth failure for several reasons, such as the mismanagement of an elimination diet or a delay in CMA diagnosis. Paediatrician recommendations stress careful nutritional guidance to manage CMA[3,6,28,29] , including the use of an adapted formula that meets the nutritional needs of non-breastfed infants and young children[30,31]. Therefore, evidence on the safety and suitability of these formulas should be obtained from children with CMA in particular, as recently reported for some eHFs[23,24] or AAFs[32,33]. Growth parameters of the children fed the TeHCF were within normal range throughout the 3-mo period, indicating that this hypoallergenic formula is safe.

Henceforth, the TeHCF constitutes a new option among the various formulas already available for the dietary management of non-breastfed children with CMA[34]. The aim of the eHCF thickening is the management of the concomitant presence of CMA and regurgitations occurring when gastro-oesophageal reflux (GER) is present[34] in some infants. Previously, a formula with non-hydrolyzed CMP supplemented with the same thickeners complex as the one in the TeHCF induced a significant decrease in the daily number of regurgitations, from 7.3 ± 3.4 to 1.1 ± 1.3, in 90 infants within 14 d[35]. Therefore, the new TeHCF deserves further investigation in a patient population whose allergic symptoms are still present because the CMP have not yet been eliminated from their diet, on the contrary to children included in the present study which had to be successfully fed an elimination diet before inclusion so that their allergic symptoms were well improved. The effect of the TeHCF on gastro-intestinal symptoms in children presenting at enrolment symptoms suggesting a CMA, including severe regurgitations, should be compared to a control formula. CMA is often difficult to separate from functional gastro-intestinal disorder (FGID) in these patients when they present adverse GI reactions to cow’s milk for several reasons: Regurgitation is the most common FGID observed in the first year of life[36,37] and occur often concurrently with other FGIDs, such as colic[38], and no pathognomonic symptom or sign exists for the diagnosis of CMA or GER disease[4,5,6,7,34]. A DBPCFC should be conducted, but because this procedure is time-consuming, expensive and requires specialized facilities, some experts suggest that it may even be more clinically relevant in daily clinical practice to propose a thickened eHF that addresses both of these conditions[39]. Moreover, the new TeHCF might be an interesting option within the context of a widely use of acid suppressant medicines in infants[40,41], despite paediatric guidelines urging physicians to exercise caution before prescribing them[34], and particularly when multiple FGIDs are present[38].

Cow’ milk protein allergy is the most frequent allergy in infant and young children. Its dietary management consists of the elimination of any cow’s milk protein from the diet. In infant and young children, infant formula has to be replaced by an adapted formula which protein do not provoke reaction. This has to be demonstrated by a double-blind placebo controlled food challenge according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

A new thickened extensively hydrolyzed casein-based formula (TeHCF) has been developed to manage concomitant presence of cow’s milk allergy (CMA) and regurgitation. However, as a first step, its hypoallergenicity had to be assessed.

The objective of this study was to assess the hypoallergenicity of a new TeHCF in children with CMA.

In children diagnosed with CMA through a double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC), the hypoallergenicity of the new thickened formula was assessed through a DBPCFC: children were randomly administered increased doses of a placebo formula or the TeHCF under double-blind conditions and medical surveillance on two separate days. In children highly suspected of CMA, the hypoallergenicity of the formula and the CMA diagnosis were assessed simultaneously during a 3-days food challenge. Immediate and late reactions occurring after the introduction of any of these formulas were thoroughly recorded by the physician at the hospital and reported by parents to the physician after hospital discharge, respectively. If the children tolerated the TeHCF during the DBPCFC, they were exclusively fed this formula during a 3-mo period

30 children have been included in the study between April 2016 to July 2017. CMA diagnosis was confirmed by a DBPCFC in 29 (mean age: 8.03 ± 7.43 mo) patients. The children all tolerated the TeHCF during both the challenge and the subsequent 3-mo feeding period, which they all completed. During the latter period, the Cow’s Milk-related Symptoms Score remained at a very low level, never exceeding its baseline value (1.4 ± 2.0), growth parameters were within World Health Organization reference standards and no adverse event related to the TeHCF was reported. Over the first week of this period, the proportion of patients with digestive discomfort significantly decreased from 20.7% (6/29) to 3.4% (1/29), P = 0.025. The proportion of satisfaction with the overall effect of the formula reported by the parents and investigator was high, as was the formula acceptability by the child. The efficacy on regurgitations in a specific population of infants having CMA and regurgitation should be assessed.

This study demonstrates that the new thickened extensively hydrolysed formula is hypoallergenic. The design of our study, allowing to combine DBPCFC for CMA diagnosis and evaluation of the hypoallergenicity reduced burden for the family while allowing a sure diagnosis of CMA. Moreover, the tolerance was not assessed only during 7 d feeding period as per the American Academy of Pediatrics but through a 3-mo feeding period, in conditions similar to daily practices.

Further studies should investigate the effect of this new thickened extensively hydrolysed formula in a patient population whose allergic symptoms are still present.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Harthoorn LF, Szajewska H S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Schoemaker AA, Sprikkelman AB, Grimshaw KE, Roberts G, Grabenhenrich L, Rosenfeld L, Siegert S, Dubakiene R, Rudzeviciene O, Reche M, Fiandor A, Papadopoulos NG, Malamitsi-Puchner A, Fiocchi A, Dahdah L, Sigurdardottir ST, Clausen M, Stańczyk-Przyłuska A, Zeman K, Mills EN, McBride D, Keil T, Beyer K. Incidence and natural history of challenge-proven cow's milk allergy in European children--EuroPrevall birth cohort. Allergy. 2015;70:963-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Koletzko S, Heine RG. Non-IgE mediated cow's milk allergy in EuroPrevall. Allergy. 2015;70:1679-1680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dupont C, Chouraqui JP, Linglart A, Bocquet A, Darmaun D, Feillet F, Frelut ML, Girardet JP, Hankard R, Rozé JC, Simeoni U, Briend A; Committee on Nutrition of the French Society of Pediatrics. Nutritional management of cow's milk allergy in children: An update. Arch Pediatr. 2018;25:236-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Luyt D, Ball H, Makwana N, Green MR, Bravin K, Nasser SM, Clark AT; Standards of Care Committee (SOCC) of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI). BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of cow's milk allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:642-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Venter C, Brown T, Shah N, Walsh J, Fox AT. Diagnosis and management of non-IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy in infancy - a UK primary care practical guide. Clin Transl Allergy. 2013;3:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Koletzko S, Niggemann B, Arato A, Dias JA, Heuschkel R, Husby S, Mearin ML, Papadopoulou A, Ruemmele FM, Staiano A, Schäppi MG, Vandenplas Y; European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. Diagnostic approach and management of cow's-milk protein allergy in infants and children: ESPGHAN GI Committee practical guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:221-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 435] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fiocchi A, Brozek J, Schünemann H, Bahna SL, von Berg A, Beyer K, Bozzola M, Bradsher J, Compalati E, Ebisawa M, Guzmán MA, Li H, Heine RG, Keith P, Lack G, Landi M, Martelli A, Rancé F, Sampson H, Stein A, Terracciano L, Vieths S; World Allergy Organization (WAO) Special Committee on Food Allergy. World Allergy Organization (WAO) Diagnosis and Rationale for Action against Cow's Milk Allergy (DRACMA) Guidelines. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21 Suppl 21:1-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000;106:346-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Commission Directive 1999/21/EC of 25 March 1999 on dietary foods for special medical purposes (Text with EEA relevance) [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2019 Jan 30]. Available from: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/1999/21/oj/eng. |

| 10. | Sampson HA, Gerth van Wijk R, Bindslev-Jensen C, Sicherer S, Teuber SS, Burks AW, Dubois AE, Beyer K, Eigenmann PA, Spergel JM, Werfel T, Chinchilli VM. Standardizing double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenges: American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology-European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology PRACTALL consensus report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1260-1274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 455] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Assa'ad AH, Bahna SL, Bock SA, Sicherer SH, Teuber SS; Adverse Reactions to Food Committee of American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Work Group report: oral food challenge testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:S365-S383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 382] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vandenplas Y, Dupont C, Eigenmann P, Host A, Kuitunen M, Ribes-Koninckx C, Shah N, Shamir R, Staiano A, Szajewska H, Von Berg A. A workshop report on the development of the Cow's Milk-related Symptom Score awareness tool for young children. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:334-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Severity scoring of atopic dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993;186:23-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1448] [Cited by in RCA: 1453] [Article Influence: 45.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Turjanmaa K, Darsow U, Niggemann B, Rancé F, Vanto T, Werfel T. EAACI/GA2LEN position paper: present status of the atopy patch test. Allergy. 2006;61:1377-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sampson HA, Bernhisel-Broadbent J, Yang E, Scanlon SM. Safety of casein hydrolysate formula in children with cow milk allergy. J Pediatr. 1991;118:520-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | WHO. The WHO Child Growth Standards [Internet]. WHO [cited 2018 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/en/. |

| 17. | Standards and Tools - INTERGROWTH-21st [Internet]. [cited 2018 Oct 10]. Available from: https://intergrowth21.tghn.org/standards-tools/. |

| 18. | Steer CD, Emond AM, Golding J, Sandhu B. The variation in stool patterns from 1 to 42 months: a population-based observational study. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:231-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Czerkies LA, Collins B, Saavedra JM. Evaluation of hypoallergenicity of a new, amino acid-based formula. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54:264-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Harvey BM, Langford JE, Harthoorn LF, Gillman SA, Green TD, Schwartz RH, Burks AW. Effects on growth and tolerance and hypoallergenicity of an amino acid-based formula with synbiotics. Pediatr Res. 2014;75:343-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vandenplas Y, Steenhout P, Planoudis Y, Grathwohl D; Althera Study Group. Treating cow's milk protein allergy: a double-blind randomized trial comparing two extensively hydrolysed formulas with probiotics. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102:990-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Vandenplas Y, De Greef E, Hauser B; Paradice Study Group. Safety and tolerance of a new extensively hydrolyzed rice protein-based formula in the management of infants with cow's milk protein allergy. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:1209-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Vandenplas Y, De Greef E, Xinias I, Vrani O, Mavroudi A, Hammoud M, Al Refai F, Khalife MC, Sayad A, Noun P, Farah A, Makhoul G, Orel R, Sokhn M, L'Homme A, Mohring MP, Merhi BA, Boulos J, El Masri H, Halut C; Allar Study Group. Safety of a thickened extensive casein hydrolysate formula. Nutrition. 2016;32:206-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dupont C, Bradatan E, Soulaines P, Nocerino R, Berni-Canani R. Tolerance and growth in children with cow's milk allergy fed a thickened extensively hydrolyzed casein-based formula. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Vandenplas Y, Salvatore S, Ribes-Koninckx C, Carvajal E, Szajewska H, Huysentruyt K. The Cow Milk Symptom Score (CoMiSSTM) in presumed healthy infants. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0200603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Meyer R. Nutritional disorders resulting from food allergy in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018;29:689-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pavić I, Kolaček S. Growth of Children with Food Allergy . Horm Res Paediatr. 2017;88:91-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Giovannini M, D'Auria E, Caffarelli C, Verduci E, Barberi S, Indinnimeo L, Iacono ID, Martelli A, Riva E, Bernardini R. Nutritional management and follow up of infants and children with food allergy: Italian Society of Pediatric Nutrition/Italian Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology Task Force Position Statement. Ital J Pediatr. 2014;40:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sackeyfio A, Senthinathan A, Kandaswamy P, Barry PW, Shaw B, Baker M; Guideline Development Group. Diagnosis and assessment of food allergy in children and young people: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2011;342:d747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Le Louer B, Lemale J, Garcette K, Orzechowski C, Chalvon A, Girardet JP, Tounian P. [Severe nutritional deficiencies in young infants with inappropriate plant milk consumption]. Arch Pediatr. 2014;21:483-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Keller MD, Shuker M, Heimall J, Cianferoni A. Severe malnutrition resulting from use of rice milk in food elimination diets for atopic dermatitis. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:40-42. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Vanderhoof J, Moore N, de Boissieu D. Evaluation of an Amino Acid-Based Formula in Infants Not Responding to Extensively Hydrolyzed Protein Formula. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63:531-533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Canani RB, Nocerino R, Frediani T, Lucarelli S, Di Scala C, Varin E, Leone L, Muraro A, Agostoni C. Amino Acid-based Formula in Cow's Milk Allergy: Long-term Effects on Body Growth and Protein Metabolism. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:632-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rosen R, Vandenplas Y, Singendonk M, Cabana M, DiLorenzo C, Gottrand F, Gupta S, Langendam M, Staiano A, Thapar N, Tipnis N, Tabbers M. Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux Clinical Practice Guidelines: Joint Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:516-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 610] [Cited by in RCA: 524] [Article Influence: 74.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Dupont C, Vandenplas Y; SONAR Study Group. Efficacy and Tolerance of a New Anti-Regurgitation Formula. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2016;19:104-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Benninga MA, Faure C, Hyman PE, St James Roberts I, Schechter NL, Nurko S. Childhood Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Neonate/Toddler. Gastroenterology. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Robin SG, Keller C, Zwiener R, Hyman PE, Nurko S, Saps M, Di Lorenzo C, Shulman RJ, Hyams JS, Palsson O, van Tilburg MAL. Prevalence of Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Utilizing the Rome IV Criteria. J Pediatr. 2018;195:134-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 30.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bellaiche M, Oozeer R, Gerardi-Temporel G, Faure C, Vandenplas Y. Multiple functional gastrointestinal disorders are frequent in formula-fed infants and decrease their quality of life. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107:1276-1282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Vandenplas Y, Gottrand F, Veereman-Wauters G, De Greef E, Devreker T, Hauser B, Benninga M, Heymans HS. Gastrointestinal manifestations of cow's milk protein allergy and gastrointestinal motility. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:1105-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Bell JC, Schneuer FJ, Harrison C, Trevena L, Hiscock H, Elshaug AG, Nassar N. Acid suppressants for managing gastro-oesophageal reflux and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in infants: a national survey. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103:660-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Blank ML, Parkin L. National Study of Off-label Proton Pump Inhibitor Use Among New Zealand Infants in the First Year of Life (2005-2012). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65:179-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |